Koren Y. The Global Manufacturing Revolution: Product-Process-Business Integration and Reconfigurable Systems

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

‘I want 10 general features plus this one specific feature. So you build a device with

1010 features. But no one wants 1010 features.” [USNWR 1/15/2001]. On the other

hand, it is not economical for a manufacturer to offer 1000 product variants (models),

each with 11 features. Therefore, the manufacturer has two choices: (1) offer several

variants, each with a package of features (options) or (2) offer personalized products,

in which camera platforms, with basic features, are produced first, and special features

are offered later, to be installed when the product is ordered and paid for (see delayed

differentiation in Chapters 6 and 11).

PROBLEMS

3.1 A famil y of toy cars is built from six different modules. Three of the modules are

the same in every variant of the toy car. Two of the remaining modules have three

alternatives (i.e., instances). The remaining sixth module is optional.

(a) What is the maximum number of possible product variants in this product

family?

(b) What is the product commonality index (PCI)?

3.2 A product family consists of four product variants. All of the differentiating

modules have two instances. Exactly one instance of each differentiating

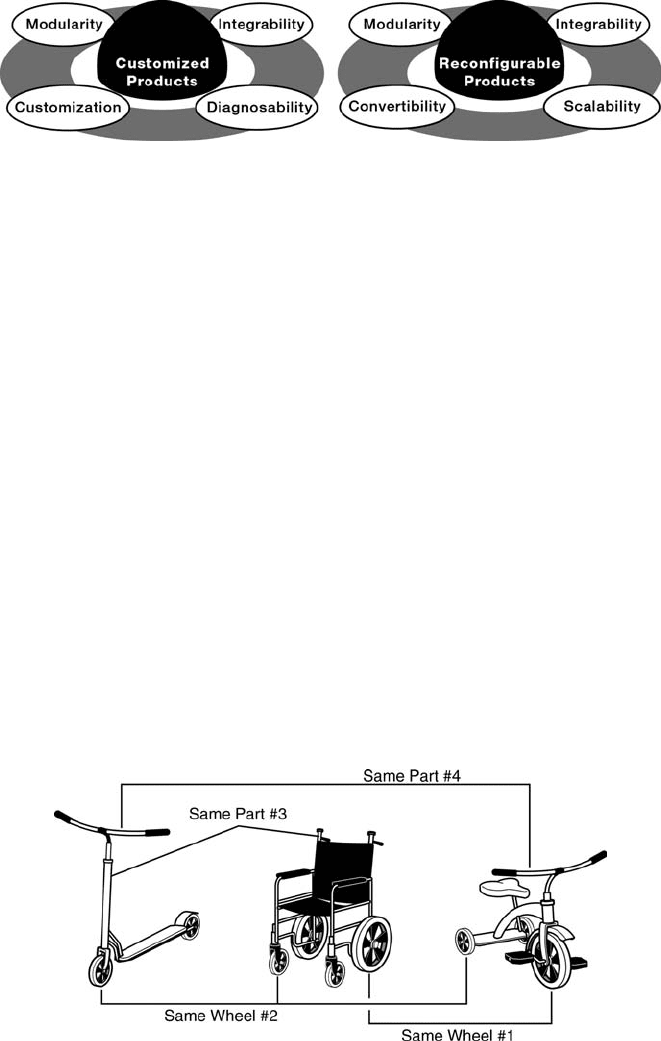

Figure 3.16 Three products with some similar components.

Figure 3.15 Successfully reconfigurable and customized products possess a set of key

characteristics.

PROBLEMS 101

module must be in every product variant. How many base modules are in the

product family if the product commonality index is 0.944?

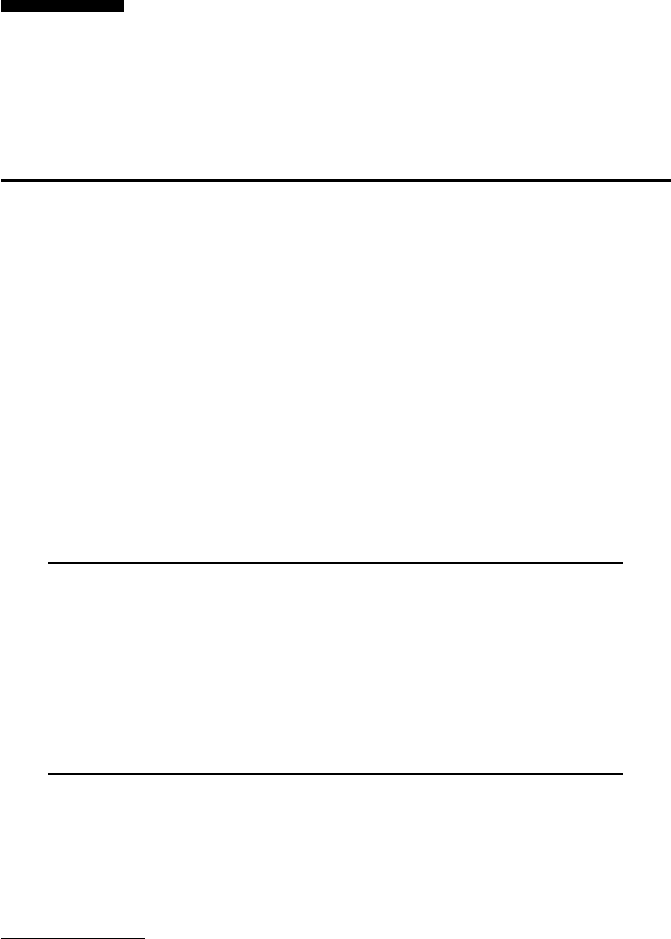

3.3 Figure 3.16 shows three products: a scooter, a wheelchair, and a tricycle. A

manufacturer defines them as a product family, and would like to produce all

three products.

(a) Make a list of parts (components) needed in each product. In addition to the

four parts that are marked, which parts may be identical (common) in at least

two products?

(b) Calculate the product commonality index.

(c) Suggest modifications in these products that increase the number of

common components that are non-differentiating (e.g., wheel chair seat

and tricycle seat are differentiating and they are supposed to be different).

3.4 Suggest product modifications aimed at making the tricycles reconfigured to

scooters as the child grow.

REFERENCES

1. D. Anderson. Agile Product Development for Mass Customization. Irwin, Chicago, 1997.

2. http://www.conceptcarz.com/vehicle/z12589/default.aspx.

3. Y. Koren, J. Barhak, and Z. Pasek. Interior Design of Automobiles, US patent pending.

4. C.R. Bo

€

er and F. Jovane. Towards a new model of sustainable production: manuFuturing.

Annals of the CIRP, Vol. 45, No. 1, 1996.

5. M. A. Aspinall and R. A. Hamermesh.Realizing the promise of personalized medicine.

Harvard Business Review, October 2007, pp. 109–117.

6. K. Ulrich and K. Tung. Fundamental of product modularity. Proceedings of ASME Annual

Meeting Symposium on Issues in Design/Manufacturing Integration, Atlanta, 1991.

7. M. V. Martin and K. Ishii. Design for variety: development of complexity indices and

design charts. Proceedings of the ASME Design Engineering Technical Conferences,

Sacramento, CA, September 1997.

8. S. Kota. Managing variety in product families through design for commonality.

Proceedings of ASME Design Engineering Technical Conference, Atlanta, GA,

September 1998.

9. S. Kota, K. Sethuraman, and R. Miller. A metric for evaluating design commonality in

product families. ASME Transactions Journal of Mechanical Design, December 2000,

Vol. 122, pp. 403–410. (The paper introduces the PCI definition.)

10. A. Bryan, S. J. Hu, and Y. Koren. Concurrent design of product families and assembly

systems. Proceedings of ASME International Manufacturing and Science Engineering

Conference, Atlanta, GA, October 2007, pp. 803–813.

11. S. Kota, K. Sthuraman, and R. Miller. A metric for evaluating design commonality in

product families. ASME Journal of Mechanical Design, December 2000, Vol. 122,

pp. 403–410.

12. C.Y. Baldwin and K.B. Clark. Modularity-in-design: an analysis based on the theory of real

options. Harvard Business Review, September–October 1994.

102

CUSTOMIZED, PERSONALIZED AND RECONFIGURABLE PRODUCTS

Chapter 4

Mass Production and Lean

Manufacturing

Mr. Henry Ford’s desire to make his “Model-T”affordable to a much larger number of

potential customers was the driver for the mass production paradigm. To accomplish

this, he had to invent a new production method that would dramatically reduce the

manufacturing cost of the product by increasing the production output. This method,

which is based on a moving assembly line, became the enabler of the mass production

paradigm. To appreciate the impact of mass production on product prices let us look at

the history of Ford Motor Company as summarized in the following table.

1896 Ford’s first automobile prototype

1903 Ford Motor Co. established

1905 95 car manufacturers in the United States

1909 Model-T: $825

Minimum salary: $2/day

1913 Ford’s moving assembly line introduced

Ford manufactures 50% of automobiles in the United States

1914 Model-T: $440

Minimum salary: $5/day

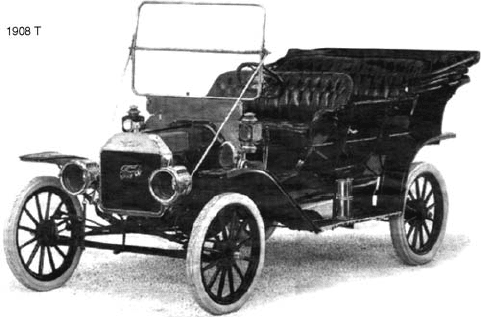

The 1908 “Model-T” is depicted in Figure 4.1. The most striking contradiction

between the “Model-T” price and the wages of the workers who built it occurred

during the 5 years from 1909 to 1914. In that period wages increased by 2.5 times,

and the Model-T’s price was cut in half!

The Global Manufacturing Revolution: Product-Process-Business Integration and Reconfigurable Systems

By Yoram Koren

Copyright 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

103

.

How could the price of the Model-T be reduced so dramatically in 5 years?

.

How can it be that wages went up so high, and at the same time the product price

went down?

.

How did Ford manage this “miracle?”

We have to thoroughly understand the principles of mass production and develop

its mathematical model in order to explain what appears as a paradox when first

observed.

4.1 THE PRINCIPLES OF MASS PRODUCTION

In craft production, one-of-a-kind parts are individually made to fit together for each

product. Mass production, however, could not exist without the invention of inter-

changeable parts.

Interchangeable Parts—The manufacture of interchangeable parts was an idea

that originate d in the early 1700s, in the making of clock gears. By the end of that

century it had become a military necessity for the manufacture and maintenance of

firearms. Soldier s needed to be able to replace parts on their weapons to stay in the

fight. The first demonstration of the interchangeability ideal came at the Harpers

Ferry Arsenal in 1827 when muskets (long guns) were assembled from pieces

selected at random from boxes of parts. It took almost 100 years for that idea to

propagate to the manufacturing of consumer products and to make the mass

production paradigm possible.

Under the craft production paradigm, flawed or irregular parts were discarded (or

improved) by craftsmen as they assembled one-of-a-kind products on an assembly

stage. Only when large quantities of identical, truly interchangeable parts were

Figure 4.1 Ford Model T. 1908: “You can have any color of a car you want, as long as it’s

black.” Henry Ford

104

MASS PRODUCTION AND LEAN MANUFACTURING

available, could Henry Ford’s mass production scheme be successful. As product

progressed from station to station, assemblers had to have parts that would fit and

could be added without alteration. Interchangeable parts made it possible for the

system to move and maintain the desired output. The availability of interchangeable

parts is a key enabler of mass production.

The opening of the moving automobile assembly line in Dearborn by the Ford

Motor Co. in 1913 is regarded as the starting point of the mass production era. The car

that Ford produced on this line was the famous Ford Model T.

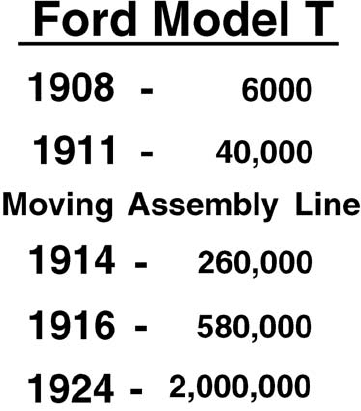

The contribution the moving assembly line made can be seen in the data below.

From 1911 to 1914 the number of cars produced increased from 40,000 to 260,000

units annually. And, in the next 10 years Ford’s annual production

increased eightfold, to 2 million units. But it is also worth noting that an earlier

sevenfold increase, from 1908 to 1911, resulted from simply organizing the

assembly work sequentially—the assembled cars were stationary and the workers

moved from one car to the next, with each group doing just a limited set of operations

on each car.

Ford’s assembly scheme essentially converted a parallel process, where small

teams of workers performed multiple tasks on a single unit, into a sequential (serial)

process, where workers perform only a small set of tasks, and then transfer the work-

in-progress to the next worker team who performed another set (approximately the

same amo unt of work effort in each step).

Henry Ford did this conversion from parallel to sequential assembly before

introducing the moving assembly line, and cut the time that a worker spent on a

car, from 9 hours to 2.3 minutes per car (i.e., the worker did the same task, taking about

2.3 minutes, and therefore became more efficient). With the moving assembly line,

THE PRINCIPLES OF MASS PRODUCTION 105

which brought the car to a stationary worker, the time per car was cut again, from 2.3 to

1.2 minutes. This was a direct saving of almost another 50% on labor, achieved just by

implementing the moving assembly line.

The cars that Ford produced were identical. His statement “You can have any color

you want, as long as it’s black“ symbolizes the limited variety of cars offered.

However, at that time, consumers were not as picky as today, needing a car just for

transportation (not as a status symbol), and they were happy just to be able to buy a car.

In 1909, wages were low—just $2 per day, and this money was needed for food,

clothes, and lodging. Only a small percentage of the U.S. population could afford a car

(similar to the situation in China in 2000).

The introduction of the sequential process, and later the moving assembly line, was

complementary to Ford’s mass production business strategy: Increased production at

low cost enabled a consequent reduction in the product price; by lowering the product

price, more people could afford to buy cars , which, in turn, expanded the market for

Ford’s cars.

Henry Ford expanded the market by reducing the price of the car from $825 to

$440. This allowed more people to afford to buy one. Instead of selling some 12,000

cars per year at $825 per car (in 1909)—revenues of $10 million—he reduced

the selling price by about 50% and sold 260,000 vehicles in 1914—a revenue of

$115 million, which is 11 times larger. This huge price decrease was enabled by

increased production capacity.

The capacity (i.e., maximum possible production volume) of the moving assembly

line was enormous compared with that of the parallel assembly method. The cost

benefits were also huge even though the innovation required new and expensive

hardware because those costs were distributed over the whole production run.

The main principle of the mass production paradigm is, therefore, as follows:

Producing a limited variety of standardized products at low cost as a strategy that

increases customer demand and allows market expansion.

But the reduction in the car price alone was not enough to create the big market

expansion that Ford envisioned. He was also concerned about the small number of

people who were currently in the car buying market. Earning a common salary of just

$2 per day, Ford’s workers were not able to buy new cars. Paying his workers more

than the prevailing wage, about $5 a day, was the second part of Ford’s strategy.

He needed to expand the market for all the cars he could make, and so he increased his

customers’ purchasing power. By increasing his workers’ salary to more than twice

what they were accustomed to earning, they saw that they could actually own one of

the cars they were building. Because of equity across industries, an increase in salaries

at Ford eventually caused an overall increase in all U.S. sal aries, and Ford’s car market

doubled again (from 260,000 units annually to 580,000 units) in just more 2 years. It is

ironic that Henry Ford, an icon of American capitalism, contributed to his workers’

wealth more than anybody else ever did.

106 MASS PRODUCTION AND LEAN MANUFACTURING

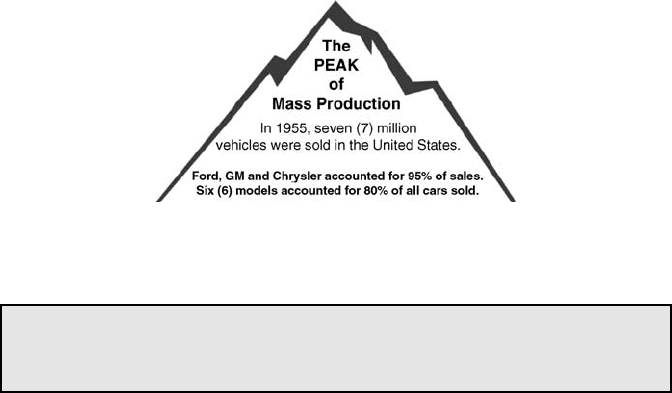

The mass production era continued from 1913 until the mid-1980s. Its peak in the

USA was around 1955, the year in which product variety was the lowest and

the volume per product was at its maximum (compared to the U.S. population at

that time).

The mass production business model may be summarized as follows:

Production of standardized products in very high volume reduces production cost,

which, in turn, allows price reduction to the benefit of the customers.

Reduced product price increases demand and sales.

Low price per unit is the focus of mass production. Mass production is not much

concerned with the customer’s preferences and needs. The mass production paradigm

assumes that as product prices are lowered, more people that can afford to buy the

products will enter the market resulting in more sales. This in turn, encourages greater

production that can be done at even lower costs, and therefore the product prices can

be further lowered, and so on.

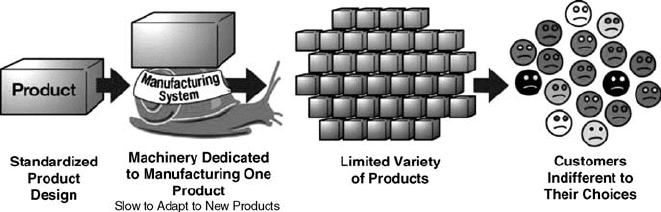

In the mass production paradigm both product and process changes come very

slowly, at a snail’s pace. But mass production manufacturers do not care where the

customers come from. They just assume they will always be there to buy their

products. The product is designed with limited variety and the manufacturing system

is designed to produce a limited product variety (see Figure 4.2).

The two most expensive elements of a manufacturing system for automotive

production are machining systems that produce the powertrain components (engine

blocks, transmission cases, etc.), and assembly systems that assemble the various

parts to a complete automobile. When automobiles are produced in mass production,

both the machining systems and the assembly systems are dedicated to produce that

one product (model), and they are doing it at very high quantities. Mass production is

based on economies of scale. Economists calculate that economies of scale reduce the

variable manufacturing cost s by approximately 15–25% for every doubling of the

produced volume. If the system produc es the planned quantities, the product cost is

inexpensive. We see, therefore, a strong link between this type of manufacturing

system and the business model goal, as defined above.

THE PRINCIPLES OF MASS PRODUCTION 107

To summarize, the goal of mass production is low-cost manufacturing. Three

enablers contribute to the achievement of this goal: (1) interchangeable parts, (2) the

moving assembly line, and (3) dedicated machinery and manufacturing systems.

Dedicated machines and systems enable cost-effective production, especially of

powertrain components, which require the mos t effort to produce and the most

expensive machinery, and therefore are the most expensive parts in automobiles.

4.2 SUPPLY AND DEMAND

The way supply and demand influence the price of a product in the market can be

shown graphically in Figure 4.3:

.

The buyers’ demand for the product is modeled on a demand curve that shows

what buyers are willing to pay relative to all buyer wishes and not related to

sellers. The demand curve is modeled for fixed conditions, such as a certain

buyer’s purchasing power (i.e., their income) and unchanged people’s tastes.

.

The seller’s willingness to supply the product is modeled by a supply curve. The

supply curve represents solely the seller’s (not the buyer’s) attitudes. A supply

curve shows that the price at which a supplier would bewillin g and able to deliver

the indicated quantity of a product to the market.

The demand and the supply curves are usually drawn just for one product

(e.g., Ford Model T). In Figure 4.3, the demand curve, a, indicates that if the product

price were equal to AO, then consumers would want to buy a quantity AC’ (or OC) of

this product. Should the price fall to BO, the quantity demanded by consumers would

increase to BD’ (or OD) because more people would be able to buy the product at the

lower price. The quantity read from the demand curve does not indicate whether or not

that quantity could be supplied at the given price. It reflects only what the consumers

want to buy and what they can afford.

Figure 4.3 also includes a supply curve b that illustrates, for example, if prices were

equal to AO, then quantity AF’ (or OF) would be supplied. If the price falls to BO, it

Figure 4.2 In mass production the product variety is limited; the manufacturing system is

dedicated to produce just this limited variety and can be changed at only a snail’s pace.

108

MASS PRODUCTION AND LEAN MANUFACTURING

will be less attractive to produce the product, and therefore the quantity that suppliers

will be willing to supply would fall to BE’ (or OE). These quantities are based only

upon the consideration of the suppliers’ decisions; they are not related to the

willingness of consumers to purchase the indicated quantities at the indicated prices.

The equilibrium in the marketplace is achieved at point Q, at which there is just one

price for which the product quantity demanded equals the quantity supplied.

Price is, of course, not the only factor that influences suppliers to sell. If the costs of

production climb, then suppliers will want to produce and sell fewer units. By

contrast, if, for example, technology increases productivity, and the cost of producing

the product goes down, then prices may be lowered and the entire supply curve is

shifted to a new position b’. The equilibrium in the marketplace is now achieved at

point Q

1

, which indicates that a larger quantity could be bought, but at a lower price

than before.

Alternatively, if a buyer’s purchasing power (i.e., income) increases, the entire

demand curve shifts to a new position, a ’ When the demand curve was at position a,

the product price had been AO, and the consumers would have been buying quantity

OC. Now, with higher incomes, they want to increase their purchases to AG’ on curve

a’. This does not mean they will succeed in buying quantity AG’at price AO. The

supply curve will influence that. The point is that because of the income rise,

consumers will want to buy larger quantities than they would previously have wanted.

The equilibrium in the marketplace between curves a’ and b’ is achieved at point Q

2

.

Henry Ford used the principles described above to increase his profits. His

invention of the moving assembly line boosted productivity and shifted the

Figure 4.3 Demand and supply curves

SUPPLY AND DEMAND 109

demand–supply equilibrium point from point Q to point Q

1

at which the product price

is lower. Then he increased the purchasing power of consumers by increasing the

wages of his workers, which, in turn, caused an overall increase in U.S. salaries. This

created a new equilibrium point Q

2

, which further increased the quantities bought by

customers, who were even willing to pay a modest increase in the vehicle price. This

shift in both the demand and supply curves increased the quantity of cars sold and

boosted Ford’s profits tremendously. This answers the question that we posed at the

beginning of this chapter: Is it not a paradox that when wages at Ford went up, its

product prices went down?

4.3 THE MATHEMATICAL MODEL OF MASS PRODUCTION

Below we present an original mathematical model for mass production. The model

shows that the mass production process behaves as a closed-loop system with positive

feedback. To understand this, we first start by defining two pricing methods, that,

although they may look similar, they provide very different perspectives.

4.3.1 Pricing

There are two perspectives on how the price of a product is derived: either (1) by

adding a profit margin to actual productio n costs or (2) by the marketplace.

Calculation by the first method is typically associated with mass production, and

the latter fits the philosophy of lean production.

In the mass production mindset, companies have held the perspective that adding a

profit to their costs dictates the selling price in the market.

Product selling price ¼ Profi t þ Fixed cost þ Variable costs

where the fixed cost includes the investment cost (machines, factory) plus other fixed

costs prorated per product (e.g., health insurance for employees and retirees), and the

variable cost includes the direct cost per product: material, labor, tools, distribution,

etc. Under this assumption, desired levels of profit are maintained, and any increase in

costresu lts in an increased price to the consumer. This pricingmethod is best applicable

in a mass production environment, characterize d by low competition and high volume

per product, and is the basis for the mathematical analysis presented in this section.

In the alternative—market-pricing method—competition determines the selling

price. Profit is a result of subtracting costs from the selling price, i.e., what the

market will bear:

Profit ¼ Product selling price Fixed cost Variable costs

Under this premise, the only way to increase profitability is to reduce the manufactur-

ing cost. This is usually done by changes in non-value-added operations, by elim-

inating waste, and by increased productivity (see Section 4.4). This pricing method

is utilized in competitive markets, and it is applicable today by global companies.

110 MASS PRODUCTION AND LEAN MANUFACTURING