Kenny Anthony. Philosophy in the Modern World: A New History of Western Philosophy. Volume 4

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

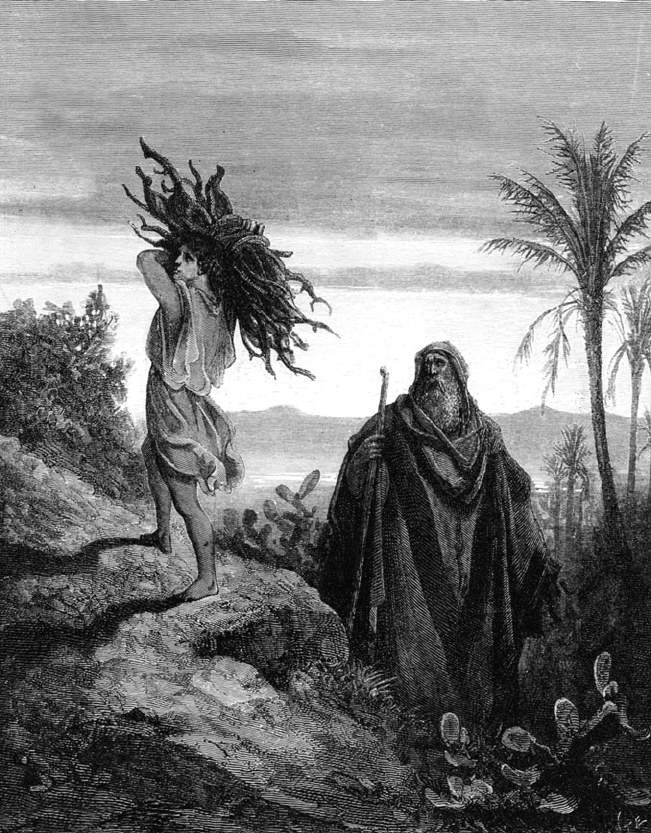

Gustav Dore

´

’s 1866 representation of the sacrifice of Abraham.

GOD

294

There is undoubtedly something heroic in Abraham’s willingness to sacri-

fice Isaac—the son for whom he had waited eighty years, and in whom all

his hope of posterity rested. But in ethical terms, is not his conduct

monstrous? He is willing to commit murder, to violate a father’s duty to

love his son, and in the course of it to deceive those closest to him.

Biblical and classical literature, Kierkegaard reminds us, offers other

examples of parents sacrificing their children: Agamemnon offering up

Iphigenia to avert the gods’ curse on the Greek expedition to Troy, Jephtha

giving up his daughter in fulfilment of a rash vow, Brutus condemning to

death his treasonable sons. These were all sacrifices made for the greater

good of a communi ty: they were, in ethical terms, a surrender of the

individual for the sake of the universal. Abraham’s sacrifice was nothing of

the kind: it was a transaction between himself and God. Had he been a

tragic hero like the others, he would, on reaching Mount Moriah, have

plunged the knife into himself rather than into Isaac. Instead, Kierkegaard

tells us, he stepped outside the realm of ethics altogether, and acted for the

sake of an altogether higher goal.

Such an action Kierkegaard calls ‘the teleological suspension of the

ethical’. Abraham’s act transgressed the ethical order in view of his higher

end, or telos, outside it. Whereas an ethical hero, such as Socrates, lays down

his life for the sake of a universal moral law, Abraham’s heroism lay in his

obedience to an individual divine command. Moreover, his action was not

just one of renunciation, like the rich young man in the gospel abandoning

his wealth: a man does not have a duty to his money as he does to his son,

and it was precisely in violating this duty that Abraham showed his

obedience to God.

Was his act then sinful? If we think of every duty as being a duty to God,

then undoubtedly it was. But such an identification of God with duty

actually empties of content the notion of duty to God himself.

The whole existence of the human race is rounded off completely like a sphere,

and the ethical is at once its limit and its content. God becomes an invisible

vanishing point, a powerless thought, His power being only in the ethical which is

the content of existence. If in any way it might occur to any man to want to love

God in any other sense, he is romantic, he loves a phantom which if it had merely

the power of being able to speak, would say to him ‘I do not require your love. Stay

where you belong’. (FT 78)

GOD

295

If there is to be a God who is more than a personification of duty, then

there must be a sphere higher than the ethical. If Abraham is a hero, as the

Bible portrays him, it can only be from the standpoint of faith. ‘For faith is

this paradox, that the particular is higher than the universal.’

Even if we accept that the demands of the unique relationship between

God and an individual may override commitments arising from general laws,

a crucial question remains. If an individual feels called to violate an ethical

law, how is he to tell whether this is a genuine divine command or a mere

temptation? Kierkegaard insists that no one else can tell him; that is why

Abraham kept his plan secret from Sarah, Isaac, and his friends. The knight

of faith (as Kierkegaard calls Abraham) has the terrible responsibility of

solitude. But how can he even know or prove to himself what is a genuine

divine command? Kierkegaard merely emphasizes that the leap of faith is

taken in blindness. His failure to offer a criterion for distinguishing genuine

from delusive vocation is something that cries out to us in an age when more

and more people feel they have a personal divine command to sacrifice their

own lives in order to kill as many innocent victims as possible.

Kierkegaard’s silence at this point is not inadvertent. In his Philosophi cal

Fragments and his Concluding Unscientific Postscript he offers a number of argu-

ments to the effect that faith is not the outcome of any objective reasoning.

The form of religious faith that he has in mind is the Christian belief that

Jesus saved the human race by his death on the cross. This belief contains

definite historical elements, and Kierkegaard asks, ‘Is it possible to base an

eternal happiness upon historical knowledge?’, and he gives three argu-

ments for a negative answer.

First, it is impossible, by objective research, to obtain certainty about any

historical event; there is always some possibility of doubt, however small,

and we never achieve more than an approximation. But faith leaves no

room for doubt; it is a resolution to reject the possibility of error. No mere

judgement of probability is sufficient for this faith which is to be the basis of

eternal happiness. Hence, faith cannot be based on objective history.

Second, historical research is never definitively concluded: it is always

being refined and revised, difficulties are always arising and being over-

come. ‘Each generation inh erits from its predecessors the illusion that the

method is quite impeccable, but the learned scholars have not yet ac hieved

success.’ If we are to take a historical document as the basis of our religious

commitment, that commitment must be perpetually postponed.

GOD

296

Third, faith must be a passionate devotion of oneself, but objective

inquiry involves an attitude of detachment. Because belief demands passion,

Kierkegaard argues that the improbability of what is believed not only is no

obstacle to faith, but is an essential element of faith. The believer must

embrace risk, for without risk there is no faith. ‘Faith is precisely the

contradiction between the infinite passion of the individual’s inwardness

and the objective uncertainty.’ The greater the risk of falsehood, the greater

the passion involved in believing. We must throw away all rational supports

of faith ‘so as to permit the absurd to stand out in all its clarity, in order that

the individual may believe if he wills it’ (P 190).

If the improbability of a belief is the measure of the passion with which it

is believed, then faith, which Kierkegaard calls ‘infinite personal passion’,

must have as its object something that is infinitely improbable. Such was

the faith of Abraham, who right up to the moment of drawing the knife on

Isaac continued to believe in the divine promise of posterity. And his faith

was rewar ded, when God’s angel held back his hand and Isaac, liberated

from the pyre, went on to become the father of many nation s.

Few believing Christians have been willing to accept that Christianity is

infinitely improbable, and non-believers are offered by Kierkegaard no

motive, not to say reason, for accepting belief. Paradoxically, his irration-

alism has been most influential not among his fellow believers, but among

twentieth-century atheists. Existentialist thinkers such as Karl Jaspers in

Germany and Jean-Paul Sartre in France found attractive his claim that to

have an authentic existence one must abandon the multitude and seize

control of one’s own destiny by a blind leap beyond reason.

The Theism of John Stuart Mill

In England, religious thought took a very different turn in the writings of

John Stuart Mill, published some fifteen years after the Concluding Unscientific

Postscript. Jeremy Bentham and James Mill had ensured that religious

instruction should form no part of John Stuart’s education. Accordingly,

in his autobiography, Mill says he is ‘one of the very few examples in this

country of one who has, not thrown off religious belief, but never had it’.

Possibly because of this, he did not feel the animus against religion that

many other utilitarians have felt. In his posthumou sly published Three

GOD

297

Essays on Religion he took a remarkably dispassion ate look at the arguments

for and against the existence of God, and at the positive and negative effects

of religious belief.

While dismissing the ontological and causal arguments for God’s existence,

Mill took seriously the argument from design, the only one based upon

experience. ‘In the present state of our knowledge’, he wrote, ‘the adaptations

in Nature afford a large balance of probability in favour of creation by

intelligence.’ He did not, however, regard the evidence as rendering even

probable the existence of an omnipotent and benevolent creator. An om-

nipotent being would have no need of the adaptation of means to ends that

provides the support of the design argument; and an omnipotent being that

permitted the amount of evil we find in the world could not be benevolent.

Still less can the God of traditional Christianity be so regarded. Recalling his

father, Mill wrote in his autobiography:

Think (he used to say) of a being who would make a Hell—who would create the

human race with the infallible foreknowledge, and therefore with the intention,

that the great majority of them were to be consigned to horrible and everlasting

torment. The time, I believe, is drawing near when this dreadful conception of an

object of worship will be no longer identified with Christianity; and when all

persons, with any sense of moral good and evil, will look upon it with the same

indignation with which my father regarded it. (A 26)

We cannot call any being good, Mill maintained, unless he possesses the

attributes that constitute goodness in our fellow creatures—‘and if such a

being can sentence me to hell for not so calling him, to hell I will go’.

But even if the notion of hell is discarded as mythical, the amount of evil

we know to exist in this world is sufficient, Mill believes, to rule out the

notion of omnipotent goodness. Mill was indeed an optimist in his judge-

ment of the world we live in: ‘all the grand sources’, Mill wrote, ‘of human

suffering are in a great degree, many of them almost entirely, conquerable

by human care and effort’ (U 266). Nonetheless, the great majority of

mankind live in misery, and if this is due largely to human incompetence

and lack of goodwill, that itself counts against the idea that we are all under

the rule of all-powerful goodness.

Mill’s essay Theism concludes as follows:

These, then, are the net results of natural theology on the question of the divine

attributes. A being of great but limited power, how or by what limited we cannot

GOD

298

even conjecture; of great and perhaps unlimited intelligence, but perhaps also

more narrowly limited power than this, who desires, and pays some regard to, the

happiness of his creatures, but who seems to have other motives of action which

he cares more for, and who can hardly be supposed to have created the universe

for that purpose alone. Such is the deity whom natural religion points to, and any

idea of God more captivating than this comes only from human wishes, or from

the teaching of either real or imaginary revelation. (3E 94)

If that is the case, what can be said about the desirability or otherwise of

religious belief ? It cannot be disputed, Mill says, that religion has value to

individuals as a source of personal satisfaction and elevated feelings. Some

religions hold out the prospect of immortality as an incentive to virtuous

behaviour. But this expectation rests on tenuous grounds; and as humanity

makes progress it may come to seem a much less flattering prospect.

It is not only possible but probable that in a higher, and above all, a happier

condition of human life, not annihilation but immortality may be the burden-

some idea; and that human nature, though pleased with the present, and by no

means impatient to quit it, would find comfort and not sadness in the thought

that it is not chained through eternity to a conscious existence which it cannot be

assured that it will always wish to preserve. (3E 122)

Creation and Evolution

By the time Mill’s Essays were published in 1887, religious believers felt

under threat more from evolutionary biology than from empiricist philo-

sophy. On the Origin of Species and The Descent of Man were greeted with horror

in some Christian circles. At the meeting of the British Association in 1860,

the evolutionist T. H. Huxley, so he reported, had been asked by the Bishop

of Oxford whether he claimed descent from an ape on his father’s or his

mother’s side. Huxley—according to his own account—replied that he

would rather have an ape for a grandfather than a man who misused his

gifts to obstruct science by rhetoric.

The quarrel between Darwinian evolutionists and Christian fundamen-

talists continues today. Darwin’s theory obviously clashes with a literal

acceptance of the Bible account of the creation of the world in seven days.

Moreover, the length of time that would be necessary for evolution to take

place would be immensely longer than the 6,000 years that Christian

GOD

299

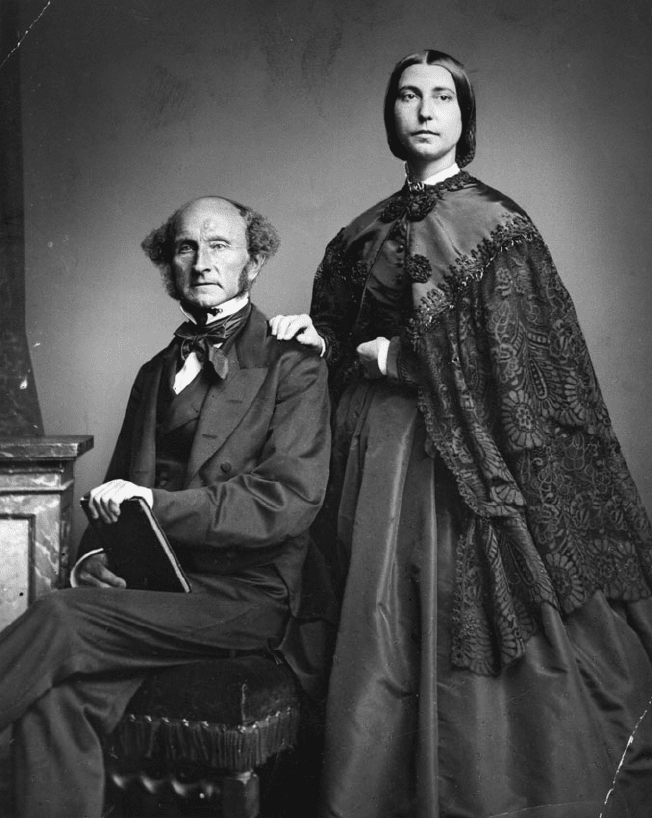

John Stuart Mill with his stepdaughter Helen who published posthumously his writings

on religion.

GOD

300

fundamentalists believe to be the age of the universe. But a non-literal

interpretation of Genesis was adopted long ago by theologians as orthodox

as St Augustine, and many Christians today are content to accept that the

earth may have existed for billions of years. It is more difficult to reconcile

an acceptance of Darwinism with belief in original sin. If the struggle for

existence had been going on for aeons before humans evolved, it is

impossible to accept that it was man’s first disobedience and the fruit of

the forbidden tree that brought death into the world.

On the other hand, it is wrong to suggest, as is often done, that Darwin

disproved the existence of God. For all Darwin showed, the whole

machinery of natural selection may have been part of a creator’s design

for the universe. After all, belief that we humans are God’s creatures has

never been regarded as incompatible with our being the children of our

parents; it is no more incompatible with us being, on both sides, descended

from the ancestors of the apes.

At most, Darwin disposed of one argument for the existence of God:

namely, the argument that the adaptation of organisms to their environ-

ment exhibits the handiwork of a benevolent creator. But even that is to

overstate the case. The only argument refuted by Darwin would be one

that said: wherever there is adaptation to environment we must see the

immediate activity of an intelligent being. But the old argument from

design did not claim this; and indeed it was an essential step in the

argument that lower animals and natural agents did not have minds.

The argument was only that the ultimate expl anation of such adaptation

must be found in intelligence; and if the argument was ever sound, then

the success of Darwinism merely inserts an extra step between the pheno-

mena to be explained and their ultimate explanation.

Darwinism leaves much to be explained. The origin of individual species

from earlier species may be explained by the mechanisms of evolutionary

pressure and selection. But these mechanisms cannot be used to explain the

origin of species as such. For one of the starting points of explanation by

natural selection is the existence of true breeding populations, namely species.

Many Darwinians claim that the origin and structure of the world and

the emergence of human life and human institutions are already fully

explained by science, so that no room is left for postulating the existence of

activity of any non-natural agent. Darwin himself was more cautious.

Though he believed that it was not necessary, in order to account for

GOD

301

the perfection of complex organs and instincts, to appeal to ‘means

superior to, though analogous with, human reason’, he explicitly left

room, in several places of the second edition of On the Origin of Species, for

the activity of a creator. In defending his theory from geological objections

he pleads that the imperfections of the geological record ‘do not overthrow

the theory of descent from a few created forms with subsequent modifi-

cation’ (OS 376). ‘I should infer from analogy’, he tells us, ‘that probably all

the organic beings which have ever lived on this earth have descended from

some one primordial form, into which life was first breathed by the

Creator’ (OS 391).

Indeed, Darwin claims it as a merit of his system that it is in accord with

what we know of the divine mode of action:

To my mind it accords better with what we know of the laws impressed on matter

by the Creator, that the production and extinction of the past and present

inhabitants of the world should have been due to secondary causes, like those

determining the birth and death of the individual. When I view all beings not as

special creations, but as the lineal descendants of some few beings which lived long

before the first bed of the Silurian system was deposited, they seem to me to

become ennobled. (OS 395)

It was special creation, not creation, that Darwin objected to.

When neo-Darwinians claim that Darwin’s insights enable us to explain

the entire cosmos, philosophical difficulties arise at three main points: the

origin of language, the origin of life, and the origin of the uni verse.

In the case of the human species there is a particular difficulty in

explaining by natural selection the origin of language, given that language

is a system of conventions. Explanation by natural selection of the origin of

a feature in a population presupposes the occurrence of that feature in

particular individuals of the population. Natural selection might favour a

certain length of leg, and the long-legged individuals in the population

might outbreed the others. But for this kind of explanation of features to

be possible, it must be possible to conceive the occurrence of the feature in

single individuals. There is no problem in describing a single individual as

having legs n metres long. But there is a problem with the idea that there

might be just a single human language-user.

It is not easy to explain how the human race may have begun to use

language by claiming that the language-using individuals among the

population were advantaged and so outbred the non-language-using

GOD

302

individuals. This is not simply because of the difficulty of seeing how

spontaneous mutation could produce a language-using individual; it is

the difficulty of seeing how anyone could be described as a language-u sing

individual at all before there was a community of language-users. Human

language is a rule-governed, communal activity, totally different from the

signalling systems to be found in non-humans. If we reflect on the social

and conventional nature of language, we must find something odd in the

idea that language may have evolved because of the advantages possessed

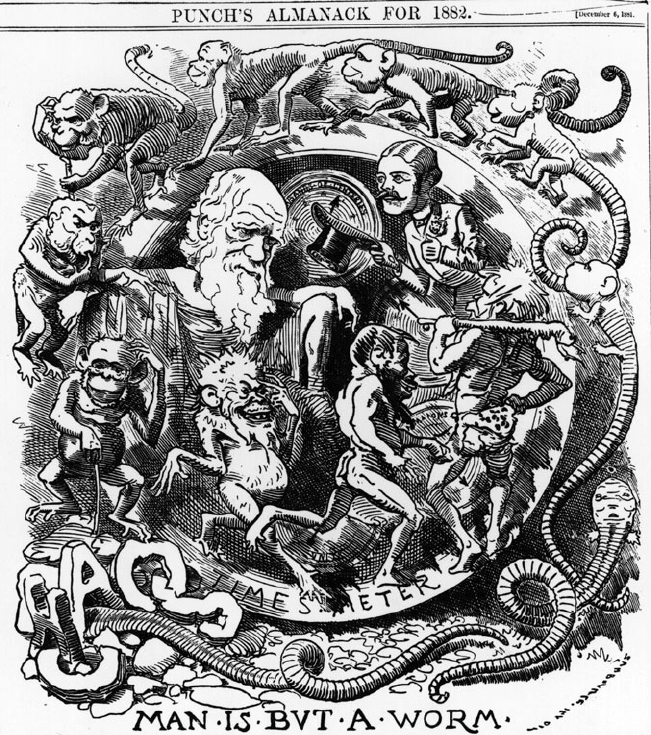

Darwin’s theory of evolution portrayed in Punch’s Almanac for 1882, twenty two years

after the publication of The Origin of Species.

GOD

303