Kenny Anthony. Philosophy in the Modern World: A New History of Western Philosophy. Volume 4

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

There are what Kant calls the formative arts, namely painting and the

plastic arts of sculpture and architecture. There is a third class of art

which creates a play of sensations: the most important of these is music.

‘Of all the arts’, says Kant, ‘poetry (which owes its origin almost entirely to

genius and will least be guided by precept or example) maintains the first

rank’ (M 170).

It is interesting to compare Kant’s ideas on aesthetics with those

expressed a few years later by the English Romantic poets. In treating of

works of art Kant as it were starts from the consumer and works back to

the producer; he begins by analysing the nature of the critic’s judgement

and ends by deducing the qualities that are necessary for genius (namely,

imagination, understanding, spirit, and taste). The Romantics, on the

other hand, start with the producer: for them, art is above all the expres-

sion of the artist’s own emotions. Wordsworth, in his Preface to Lyrical Ballads,

tells us that what distinguishes the poet from other men is that he

has a greater promptness of thought and feeling without immediate

external excitement, and a greater power of expressing such thoughts

and feelings:

Poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from

emotion recollected in tranquillity: the emotion is contemplated till, by a species

of reaction, the tranquillity gradually disappears, and an emotion, kindred to that

which was before the subject of contemplation, is gradually produced and does

itself actually exist in the mind.

In giving expression to this emotion in verse, the poet’s fundamental

obligation is to give immediate pleasure to the reader.

Coleridge agreed with this. ‘A poem’, he wrote, ‘is that species of

composition, which is opposed to works of science, by proposing for its

immediate object pleasure, not truth.’ But in describing the nature of poetic

genius Coleridge improved on both Kant and Wordsworth, by identifying

a special necessary gift. Whereas Kant and earlier authors had regarded the

imagination as a faculty common to all human beings—the capacity to

recall and reshuffle the experiences of everyday life—Coleridge preferred

to call this banal, if important, capacity ‘the fancy’. The imagination, truly

so called, was the special creative gift of the artist: in its primary form it was

nothing less than ‘the living Power and prime Agent of all human

Perception, and as a representation in the finite mind of the eternal act

AESTHETICS

254

of creation in the infinite I AM’. So Coleridge wrote in 1817 in the

thirteenth chapter of his Biographia Literaria; and from that day to this critics

and philosophers have debated the exact nature of this lofty faculty.

The Aesthetics of Schopenhauer

No philosopher has given aesthetics a more important role in his total

system than Schopenhauer. The third book of The World as Will and Idea is

largely devoted to the nature of art. Aesthetic pleasure, Schopenhauer tells

us, following in Kant’s footsteps, consists in the disinterested contempla-

tion of nature or of artefacts. When we view a work of art—a nude

sculpture, say—it may arouse desire in us: sexual desire perhaps, or desire

to acquire the statue. If so, we are still under the influence of will, and we

are not in a state of contemplation. It is only when we view something and

admire its beauty without thought of our own desires and needs that we

are treating it as a work of art and enjoying an aesthetic experience.

Disinterested contemplation, which liberates us from the tyranny of the

will, may take one of two forms, which Schopenhauer illustrates by

describing two different natural landscapes. If the scene I am contemplat-

ing absorbs my attention without effort, then it is my sense of beauty that is

aroused. But if the scene is a threatening one, and I have to struggle to

escape from fear and achieve a state of contemplation, then what I am

encountering is something that is sublime rather than beautiful. Schopen-

hauer, like Kant, calls up various scenes to illustrate the sense of the

sublime: foaming torrents pouring between overhanging rocks beneath a

sky of thunderclouds; a storm at sea with the waves dashing against cliffs

and sending spray into the air amid lightning flashes. In such cases, he says:

In the undismayed beholder, the two-fold nature of his consciousness reaches the

highest degree of distinctness. He perceives himself, on the one hand, as an

individual, as the frail phenomenon of will, which the slightest touch of these

forces can utterly destroy, helpless against powerful nature, dependent, the victim

of chance, a vanishing nothing in the presence of stupendous might; and, on the

other hand, as the eternal, serene, knowing subject, who as the condition of every

object is the sustainer of this whole world, the fearful strife of nature being only

his own idea, and he himself free and apart from all desire and necessity in the

contemplation of the Ideas. This is the full impression of the sublime. (WWI 205)

AESTHETICS

255

The impress ion produced in this way may be called ‘the dynamical sub-

lime’. But the same impression may be produced by calm meditation on

the immensity of space and time while contemplating the starry sky at

night. This impression of sublimity (which Schopenhauer, borrowing

Kant’s unhelpful term, calls ‘the mathematical sublime’) can be produced

also by voluminous closed spaces such as the dome of St Peter’s in Rome

and by monuments of great age such as the pyramids. In each case the

sense arises from the contrast between our own smallness and insignifi-

cance as individuals and a vastness that is the creation of ourselves as pure

knowing subjects.

The sublime is, as it were, the upper bound of the beautiful. Its lower

bound is what Schopenhauer calls ‘the charming’. Whereas what is sublime

makes an object of contemplation out of what is hostile to the will, the

charming turns an object of contemplation into something that attracts

the will. Schopenhauer gives as instances sculptures of ‘naked figures,

whose position, drapery, and general treatment are calculated to excite

the passions of the beholder’ and, less convincingly, Dutch still lifes of

‘oysters, herrings, crabs, bread and butter, beer, wine, and so forth’. Such

artefacts nullify the aesthetic purposes, and are altogether to be con-

demned (WWI 208).

There are two elements in every encounter with beauty: a will-less

knowing subject, and an object which is the Idea known. In contemplation

of natural beauty and of architecture, the pleasure is principally in the

purity and painlessness of the knowing, because the Ideas encountered are

low-grade manifestations of will. But when we contemplate human beings

(through the medium of tragedy, for example) the pleasure is rather in the

Ideas contemplated, which are varied, rich, and significant. On the basis of

this distinction, Schopenhauer proceeds to grade the fine arts.

Lowest in the scale comes architecture, which brings out low-grade Ideas

such as gravity, rigidity, and light:

The beauty of a building lies in the obvious adaptation of every part ...to the

stability of the whole, to which the position, size and form of every part have so

necessary a relation that if it were possible to remove some part, the whole would

inevitably collapse. For only by each part bearing as much as it conveniently can,

and each being supported exactly where it ought to be and to exactly the necessary

extent, does this play of opposition, this conflict between rigidity and gravity, that

AESTHETICS

256

constitutes the life of the stone and the manifestation of its will, unfold itself in the

most complete visibility. (WWI 215)

Of course, architecture serves a practical as well as an aesthetic purpose, but

the greatness of an architect shows itself in the way he achieves pure aesthetic

ends in spite of having to subordinate them to the needs of his client.

The representational arts, in Schopenhauer’s view, are concerned with

the universal rather than the particular. Paintings or sculptures of animals,

he is convinced, are obviously concerned with the species, not the individ-

ual: ‘the most typical lion, wolf, horse, sheep, or ox, is always the most

beautiful also’. But with representations of human beings, the matter is

more complicated. It is quite wrong to think that art achieves beauty by

imitating nature. How could an artist recognize the perfect sample to

imitate if he did not have an a priori pattern of beauty in his mind? And

has nature ever produced a human being perfectly beautiful in every

respect? What the artist understands is something that nature only stam-

mers in half-uttered speech. The sculpto r ‘expresses in the hard marble

that beauty of form which in a thousand attempts nature failed to produce,

and presents it to her as if telling her ‘‘This is what you wanted to say’’ ’

(WWI 222).

The general idea of humanity has to be represented by the sculptor or

painter in the character of an individual, and it can be presented in

individuals of various kinds. In a genre picture, it does not matter ‘whether

ministers discuss the fate of countries and nations over a map, or boors

wrangle in a beer-house over cards and dice’. Nor does it matter whether

the characters represented in a work of art are historical rather than

fictional: the link with a historical personage gives a painting its nominal

significance, not its real significance.

For example, Moses found by the Egyptian princess is the nominal significance of

a painting; it represents a moment of the greatest importance in history; the real

significance, on the other hand, that which is really given to the onlooker, is

a foundling child rescued from its floating cradle by a great lady, an incident which

may have happened more than once. (WWI 231)

Because of this, the paintings of Renaissance painters that Schopenhauer

most admired were not those that represented a particular event (such as

the nativity or the Crucifixion) but rather simple groups of saints alongside

AESTHETICS

257

the Saviour, e ngaged in no action. In the faces and eyes of such figures we

see the expression of that suppression of will which is the summit of all art.

Schopenhauer’s theory of art combines elements from Plato and elem-

ents from Aristotle. The purpose of art, he believed was to represent not a

particular individual, nor an abstract concept, but a Platonic Idea. But

whereas Plato condemned art works as being at two removes from the

Ideas, copies of material things that themselves were only imitations of

Ideas, Schopenhauer thinks that the artist comes closer to the ideal than

the technician or the historian. This is particularly the case with poetry and

drama, the highest of the arts. History is related to poetry as portrait

painting is to historical painting: the one gives us truth in the individual,

and the other truth in the universal. Like Aristotle, Schopenhauer con-

cludes that far more inner truth is to be attributed to poetry than to

history. And among historical narratives, he decides rather eccentrically,

the greatest value is to be attributed to autobiographies.

Kierkegaard on Music

In Kierkegaard’s works, the word ‘aesthetic’ and its cognates occur freq-

uently. However, for him ‘aesthetic’ is an ethical rather than an aesthetic

category. The aesthetic character is someone who devotes his life to the

pursuit of immediate pleasure; and the pleasures he pursues may be

natural (such as food, drink, and sex) no less than artistic (such as painting,

music, and dance). Kierkegaard’s main interest in discussing the aesthetic

attitude to life (notably in Either/Or) is to stress its superficial and funda-

mentally unsatisfactory nature, and to press the claims of a profounder

ethical, and eventually religious, commitment. But in the course of a

detailed presentation of the aesthetic life he has occasion to discuss issues

that are aesthetic in the narrower sense of being concerned with the nature

of art. For instance, the first part of Either/Or contains a long section that is

subtitled ‘The Musical Erotic’.

The essay, which purports to be written by an ardent exponent of

aesthetic hedonism, is largely a meditation on Mozart’s opera Don Giovanni.

Don Juan is the supreme personification of erotic desire, and Mozart’s

opera is its uniquely perfect expression. Music, we are told, is of all the arts

the one most capable of expressing sheer sensuality. The rather unexpected

AESTHETICS

258

reason we are given for this is that music is the most abstract of the arts.

Like language, it addresses the ear; like the spoken word, it unfolds in time,

not in space. But while language is the vehicle of spirit, music is the vehicle

of sensuality.

Kierkegaard’s essayist goes on to make a surprising claim. Though religious

puritans are suspicious of music, as the voice of sensuality, and prefer to listen

to the word of the spirit, the development of music and the discovery of

sensuality are both in fact due to Christianity. Sensual love was, of course, an

element in the life of the Greeks, whether humans or gods; but it took

Christianity to separate out sensuality by contrasting it with spirituality.

If I imagine the sensual erotic as a principle, as a power, as a realm characterized by

spirit, that is to say characterized by being excluded by spirit, if I imagine it

concentrated in a single individual, then I have the concept of the spirit of the

sensual erotic. This is an idea which the Greeks did not have, which Christianity

first introduced to the world, if only in an indirect sense.

If this spirit of the sensual erotic in all its immediacy demands expression, the

question is: what medium lends itself to that? What must be especially borne in

mind here is that it demands expression and representation in its immediacy. In its

mediate state and its reflection in something else it comes under language and

becomes subject to ethical categories. In its immediacy it can only be expressed in

music. (E/O 75)

Kierkegaard illustrates the various forms and stages of erotic pursuit by

taking characters from different Mozart operas. The first awakening of

sensuality takes a melancholy, diffuse form, with no specific object: this is

the dreamy stage expressed by Cherubino in The Marriage of Figaro. The second

stage is expressed in the merry, vigorous, sparkling chirping of Papageno in

The Magic Flute: love seeking out a specific object. But these stages are no more

than presentiments of Don Giovanni, who is the very incarnation of the

sensual erotic. Ballads and legends represent him as an individual. ‘When he

is interpreted in music, on the other hand, I do not have a particular

individual, I have the power of nature, the demonic, which as little tires of

seducing, or is done with seducing, as the wind is tired of raging, the sea of

surging, or a waterfall of cascading down from its height’ (E/O 90).

Because Don Giovann i seduces not by stratagem, but by sheer energy of

desire, he does not come within any ethical category; that is why his force

can be expressed in music alone. The secret of the whole opera is that its

hero is the force animating the other characters: he is the sun, the other

AESTHETICS

259

characters mere planets, who are half in darkness, with only that side

which is turned towards him illuminated. Only the Commendatore is

independent; but he is outside the substance of the opera as its antecedent

and consequent, and both before and after his death he is the voice of spirit.

Because music is uniquely suitable to express the immediacy of sensual

desire, in Don Giovanni we have a perfect match of subject matter and

creative form. Both matter and form are essential to a work of art,

Kierkegaard says, even though philosophers overemphasize now one and

now the other. It is because of this that Don Giovanni, even if it stood alone,

was enough to make Mozart a classic composer and absolutely immortal.

Nietzsche on Tragedy

For the young Nietzsche it is not Mozart but Wagner whose operas are

supreme. This is because of a shared debt to Schopenhauer. In 1854 Wagner

wrote to Franz Liszt that Schopenhauer had come into his life like a gift

from heaven. ‘His chief idea, the final negation of the desire for life, is

terribly gloomy, but it shows the only salvation possible.’1 In his The Birth of

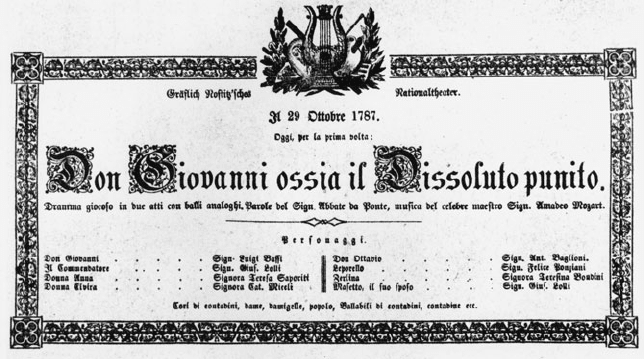

A paybill for the Prague premiere of Don Giovanni, which Kierkegaard

argued was the most perfect possible opera.

1 A. Goldman, Wagner on Music and Drama (New York: Dutton, 1966).

AESTHETICS

260

Tragedy (1872) Nietzsche likewise bases his aesthetic theory on Schopen-

hauer’s pessimistic view of life, taking as his text the Greek myth of King

Midas’ quest for the satyr Silenus.

When Silenus was finally in his power, the king asked him what was the best and

most desirable thing for mankind. The daemon stood in silence, stiff and motion-

less, but when the king insisted he broke out into a shrill laugh and said

‘Wretched, ephemeral race, children of misery and chance, why do you force

me to say what it would be more expedient for you not to hear? The best of all

things is quite beyond your reach: it is not to have been born, not to be at all, to be

nothing. The next best thing is to die as soon as may be.’ (BT 22)

Schopenhauer had held out art as the most accessible escape from the

tyranny of life.

Nietzsche, too, sees the origin of art in humans’ need to mask life’s

misery from themselves. The ancient Greeks, he tells us, in order to be able

to live at all ‘had to interpose the radiant dream-birth of the Olympian

gods between themselves and the horrors of existence’ (BT 22). There are

two kinds of escape from reality: dreaming and intoxication. In Greek

mythology, according to Nietzsche, these two forms of illusion are per-

sonified in two different gods: Apo llo, the god of light, and Dionysus, the

god of wine. ‘The development and progress of Art originates from the

duality of the Apolline and the Dionysiac, just as reproduction depends on

the duality of the sexes’. (BT 14).

The prototype of the Apolline artist is Homer, the founder of epic

poetry; he is the creator of the resplendent dream-world of the Olympic

deities. Apollo is an ethical deity, imposing measure and order on his

followers in the interests of beauty. But the Apolline magnificence is

soon engulfed in a Dionysiac flood, the stream of life that breaks down

barriers and constraints. The followers of Dionysus sing and dance in

rapturous ecstasy, enjoying life to excess. Music is the supreme expression

of the Dionysiac spirit, as epic is of the Apolline.

The glory of Greek culture is Athenian tragedy, and this is the offspring

of both Apollo and Dionysus, combining music with poetry. The choruses

in Greek tragedy represent the world of Dionysus, while the dialogue plays

itself out in a lucid Apolline world of images. The Greek spirit found its

supreme expression in the plays of Aeschylus (especially Prometheus Vinctus)

and Sophocles (especially Oedipus Rex). But with the plays of the third

AESTHETICS

261

famous tragedian, Euripides, tragedy dies by its own hand, poisoned by an

injection of rationality. The blame for this must be laid at the door of

Socrates, who inaugurated a new era that valued science above art.

Socrates, according to Nietzsche, was the antithesis of all that made

Greece great. His instincts were entirely negative and critical, rather than

positive and creative. In rejecting the Dionysiac element he destroyed the

tragedians’ synthesis. ‘We need only consider the Socratic maxims ‘‘Virtue

is knowledge, all sins arise from ignorance, the virtuous man is the happy

man’’. In these three basic optimistic formulae lies the death of tragedy’ (BT

69). Tragedy, in Euripides, took the death-leap into bourgeois theatre. The

dying Socrates, freed by insight and reason from the fear of death, became

the mystagogue of science.

Was it possible, in modern Germany, to remedy the disease inherited

from Socrates, and to restore the union of Apollo and Dionysus? Nietzsche

had no appreciation of the novel, which in the nineteenth century might be

thought the genre most fertile of the beneficent illusion that in his view was

the function of art. The novel, he thought, was essentially a Socratic art

form, that subordinated poetry to philoso phy. Oddly, he blamed its inven-

tion on Plato. ‘The Platonic dialogue might be described as the lifeboat in

which the shipwrecked older poetry and all its children escaped, crammed

together in a narrow space and fearfully obeying a single pilot, Socrates . . .

Plato gave posterity the model for a new art form—the novel’ (BT 69). Nor

had Nietzsche any high opinion of Italian opera, in spite of the combination

of poetry and music it involved. He complained that it was ruined by the

separation between recitative and aria, which privileged the verbal over the

musical. Only in Germany was there hope of a rebirth of tragedy:

From the Dionysiac soil of the German spirit a power has risen that has nothing in

common with the original conditions of Socratic culture: that culture can neither

explain nor excuse it, but instead finds it terrifying and inexplicable, powerful and

hostile—German Music, as we know it pre-eminently in its mighty sun-cycle from

Bach to Beethoven, from Beethoven to Wagner. (BT 94)

The Birth of Tragedy peters out into a set of rapturous and incoherent

programme notes to the third act of Tristan und Isolde. No one has con-

demned their weaknesses with more force than Nietzsche himself, who

after he had emerged from the spell of Wagner prefaced later editions of

the book with an ‘Attempt at Self-Criticism’. There he recants his attempt

AESTHETICS

262

to link the genius of Greece with a fictional ‘German Spirit’. But he did not

disown what he came to see as the fundamental theme of the book,

namely, that art and not morality is the properly metaphysical activity of

man, and that the existence of the world finds justification only as an

aesthetic phenomenon.

Art and Morality

For Nietzsche, art is not only autonomous but is supreme over morality. At

the opposite pole from Nietzsche stand two nineteenth-century aestheti-

cians who saw art and morality as inextricably intertwined. One was John

Ruskin (1819–1900), and the other Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910).

Ruskin regarded art as a very serious matter. In his massive work Modern

Painters (1843) he wrote:

Art, properly so called, is no recreation; it cannot be learned at spare moments,

nor pursued when we have nothing better to do. It is no handiwork for drawing-

room tables, no relief of the ennui of boudoirs; it must be understood and

undertaken seriously, or not at all. To advance it men’s lives must be given, and

to receive it their hearts.2

But the demands made by art could be justified only by the seriousness of its

moral purpose: namely, to reveal fundamental feature s of the universe.

Beauty is something objective, not a mere product of custom. The experi-

ence of beauty arises from a truthful perception of nature, and leads on to

an apprehension of the divine. Only if an artist is himself a morally good

person will he be able to deliver this revelation in an incorrupt form, and set

before us the glory of God. But in a decaying society— as Ruskin believed

nineteenth-century industrial society to be—both moral and artistic purity

are almost impossible to achieve. Both the imaginative faculty that creates,

and the ‘theoretic’ faculty that appreciates, are radically corrupt. Work is

degraded by the modern division of labour, and the workman deprived of

his due status as a craftsman seeking perfection.

Ruskin applied his moralizing theory of art to two arts in particular:

painting and architecture. Painting, for him, is essentially a form of

language: technical skill is no more than mastery of the language, and

2 John Ruskin, Selected Writings (London: Dent, 1995).

AESTHETICS

263