Hull J.C. Risk management and Financial institutions

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Financial Products and How They Are Used for Hedging 31

Suppose an investor instructs a broker to short 500 IBM shares. The

broker will carry out the instructions by borrowing the shares from

another client and selling them on an exchange in the usual way. The

investor can maintain the short position for as long as desired, provided

there are always shares available for the broker to borrow. At some stage,

however, the investor will close out the position by purchasing 500 IBM

shares. These are then replaced in the account of the client from which

the shares were borrowed. The investor takes a profit if the stock price

has declined and a loss if it has risen. If, at any time while the contract is

open, the broker runs out of shares to borrow, the investor is short-

squeezed and is forced to close out the position immediately, even if not

ready to do so.

An investor with a short position must pay to the broker any income,

such as dividends or interest, that would normally be received on the

securities that have been shorted. The broker will transfer this to the client

account from which the securities have been borrowed. Consider the

position of an investor who shorts 500 shares in April when the price

per share is $120 and closes out the position by buying them back in July

when the price per share is $100. Suppose that a dividend of $1 per share

is paid in May. The investor receives 500 x $120 = $60,000 in April when

the short position is initiated. The dividend leads to a payment by the

investor of 500 x $1 = $500 in May. The investor also pays

500 x $100 = $50,000 for shares when the position is closed out in July.

The net gain is, therefore,

$60,000 - $500 - $50,000 = $9,500

Table 2.2 illustrates this example and shows that the cash flows from the

short sale are the mirror image of the cash flows from purchasing the

shares in April and selling them in July.

An investor entering into a short position is required to maintain a

margin account with the broker. The margin account consists of cash or

marketable securities deposited by the investor with the broker to guaran-

tee that the investor will not walk away from the short position if the

share price increases. An initial margin is deposited and, if there are

adverse movements (i.e., increases) in the price of the asset that is being

shorted, additional margin may be required. The margin account does

not represent a cost to the investor. This is because interest is usually paid

on the balance in margin accounts and, if the interest rate offered is

unacceptable, marketable securities such as Treasury bills can be used to

32

Chapter 2

Table 2.2 Cash flows from short sale and purchase of shares.

Purchase of Shares

April: Purchase 500 shares for $120 -$60,000

May: Receive dividend +$500

July: Sell 500 shares for $100 per share +$50,000

Net profit = -$9, 500

Short Sale of Shares

April: Borrow 500 shares and sell them for $120 +$60,000

May: Pay dividend -$500

July: Buy 500 shares for $100 per share -$50,000

Replace borrowed shares to close short position

Net profit = +$9, 500

meet margin requirements. The proceeds of the sale of the asset belong to

the investor and normally form part of the initial margin.

Forward Contracts

A forward contract is an agreement to buy an asset in the future for a

certain price. Forward contracts trade in the over-the-counter market.

One of the parties to a forward contract assumes a long position and

agrees to buy the underlying asset on a certain specified future date for a

certain specified price. The other party assumes a short position and

agrees to sell the asset on the same date for the same price.

Forward contracts on foreign exchange are very popular. Table 2.3

provides quotes on the exchange rate between the British pound (GBP)

and the US dollar (USD) that might be provided by a large international

Table 2.3 Spot and forward quotes for the

USD/GBP exchange rate, August 5, 2005 (GBP =

British pound; USD = US dollar; quote is number

of USD per GBP).

Spot

1-month forward

3-month forward

6-month forward

Bid

1.7794

1.7780

1.7761

1.7749

Offer

1.7798

1.7785

1.7766

1.7755

April: Purchase 500 shares for $120

May: Receive dividend

July: Sell 500 shares for $100 per share

Net profit = -$9, 500

Short Sale of Shares

April: Borrow 500 shares and sell them for $120

May: Pay dividend

July: Buy 500 shares for $100 per share

Replace borrowed shares to close short

Net profit = +$9, 500

position

-$60,000

+$500

+$50,000

+$60,000

-$500

-$50,000

Financial Products and How They Are Used for Hedging 33

bank on August 5, 2005. The quotes are for the number of USD per GBP.

The first row indicates that the bank is prepared to buy GBP (also known

as sterling) in the spot market (i.e., for virtually immediate delivery) at the

rate of $1.7794 per GBP and sell sterling in the spot market at $1.7798 per

GBP; the second row indicates that the bank is prepared to buy sterling in

one month's time at $1.7780 per GBP and sell sterling in one month at

$1.7785 per GBP; and so on.

Forward contracts can be used to hedge foreign currency risk. Suppose

that on August 5, 2005, the treasurer of a US corporation knows that the

corporation will pay £1 million in six months (on February 5, 2006) and

wants to hedge against exchange rate moves. The treasurer can agree to

buy £1 million six months forward at an exchange rate of 1.7755 by

trading with the bank providing the quotes in Table 2.3. The corporation

then has a long forward contract on GBP. It has agreed that on February

5, 2006, it will buy £1 million from the bank for $1.7755 million. The

bank has a short forward contract on GBP. It has agreed that on

February 5, 2006, it will sell £1 million for $1.7755 million. Both the

corporation and the bank have made a binding commitment.

What are the possible outcomes in the trade we have just described?

The forward contract obligates the corporation to buy £1 million for

$1,775,500 and the bank to sell £1 million for this amount. If the spot

exchange rate rose to, say, 1.8000 at the end of the six months the forward

contract would be worth +$24,500 (= $1,800,000 - $1,775,500) to the

corporation and -$24,500 to the bank. It would enable 1 million pounds

to be purchased at 1.7755 rather than 1.8000. Similarly, if the spot

exchange rate fell to 1.6000 at the end of the six months, the forward

contract would have a value of -$175,500 to the corporation and a value

of +$175,500 to the bank because it would lead to the corporation paying

$175,500 more than the market price for the sterling.

In general, the payoff from a long position in a forward contract on one

unit of an asset is

S

T

—

K

where K is the delivery price and S

T

is the spot price of the asset at

maturity of the contract. This is because the holder of the contract is

obligated to buy an asset worth S

T

for K. Similarly, the payoff from a

short position in a forward contract on one unit of an asset is

K

—

S

T

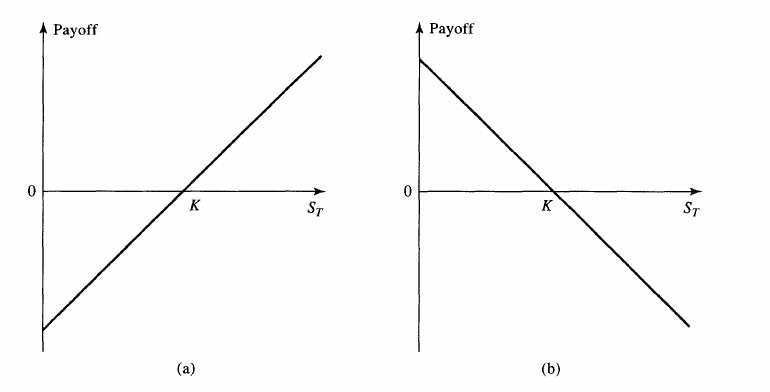

These payoffs can be positive or negative. They are illustrated in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1 Payoffs from forward contracts: (a) long position and (b) short

position. Delivery price = K; price of asset at contract maturity = S

T

.

Because it costs nothing to enter into a forward contract, the payoff from

the contract is also the trader's total gain or loss from the contract.

Futures Contracts

Futures contracts like forward contracts are agreements to buy an asset at

a future time. Unlike forward contracts, futures are traded on an ex-

change. This means that the contracts that trade are standardized. The

exchange defines the amount of the asset underlying one contract, when

delivery can be made, exactly what can be delivered, and so on. Contracts

are referred to by their delivery month. For example the September 2007

gold futures is a contract where delivery is made in September 2007. (The

precise times, delivery locations, etc., are defined by the exchange.)

One of the attractive features of futures contracts is that it is easy to close

out a position. If you buy (i.e., take a long position in) a September gold

futures contract in March you can exit in June by selling (i.e., taking a short

position in) the same contract. In forward contracts final delivery of the

underlying asset is usually made. Futures contracts by contrast are usually

closed out before the delivery month is reached. Business Snapshot 2.1 is

an amusing story indicating a potential pitfall in closing out contracts.

Futures contracts are different from forward contracts in that they are

settled daily. If the futures price moves in your favor during a day, you

make an immediate gain. If it moves in the opposite direction, you make

34 Chapter 2

Business Snapshot 2.1 The Unanticipated Delivery of a Futures Contract

This story (which may well be apocryphal) was told to the author of this book

by a senior executive of a financial institution. It concerns a new employee of the

financial institution who had not previously worked in the financial sector. One

of the clients of the financial institution regularly entered into a long futures

contract on live cattle for hedging purposes and issued instructions to close out

the position on the last day of trading. (Live cattle futures contracts trade on the

Chicago Mercantile Exchange and each contract is on 40.000 pounds of cattle.)

The new employee was given responsibility for handling the account.

When the time came to close out a contract, the employee noted that the

client was long one contract and instructed a trader at the exchange to go long

(not short) one contract. The result of this mistake was that the financial

institution ended up with a long position in two live cattle futures contracts.

By the time the mistake was spotted, trading in the contract had ceased.

The financial institution (not the client) was responsible for the mistake. As

a result, it started to look into the details of the delivery arrangements for live

cattle futures contracts something it had never done before. Under the terms

of the contract, cattle could be delivered by the party with the short position

to a number of different locations in the United States during the delivery

month. Because it was long the financial institution could do nothing but wait

for a party with a short position to issue a notice of intention to deliver to the

exchange and for the exchange to assign that notice to the financial institution.

It eventually received a notice from the exchange and found that it would

receive live cattle at a location 2,000 miles away the following Tuesday. The new

employee was dispatched to the location to handle things. It turned out that the

location had a cattle auction every Tuesday. The party with the short position

that was making delivery bought cattle at the auction and then immediately

delivered them. Unfortunately, the cattle could not be resold until the next cattle

auction the following Tuesday. The employee was therefore faced with the

problem of making arrangements for the cattle to be housed and fed for a

week. This was a great start to a first job in the financial sector!

an immediate loss. Consider what happens when you buy one Septem-

ber gold futures contract on the Chicago Board of Trade when the

futures price is $580 per ounce. The contract is on 100 ounces of gold.

You must maintain a margin account with your broker. As in the case

of a short sale, this consists of cash or marketable securities and is to

ensure that you will honor your commitments under the contract. The

rules for determining the initial amount that must be deposited in a

margin account, when it must be topped up, and so on, are set by the

exchange.

Financial Products and How They Are Used for Hedging 35

36

Chapter 2

Suppose that the initial margin requirement on your gold trade is

$2000. If, by close of trading on the first day you hold the contract,

the September gold futures price has dropped from $580 to $578, then

you lose 2 x 100 or $200. This is because you agreed to buy gold in

September for $580 and the going price for September gold is now $578.

The balance in your margin account would be reduced from $2,000 to

$1,800. If, at close of trading the next day, the September futures price is

$577, then you lose a further $100 from your margin account. If the

decline continues, you will at some stage be asked to add cash to your

margin account. If you do not do so, your broker will close out your

position.

In the example we have just considered, the price of gold moved against

you. If instead it moved in your favor, funds would be added to your

margin account. The Exchange Clearinghouse is responsible for man-

aging the flow of funds from investors with short positions to investors

with long positions when the futures price increases and the flow of funds

in the opposite direction when the futures price declines.

The relationship between futures or forward prices and spot prices is

given in Appendix A at the end of the book.

Swaps

The first swap contracts were negotiated in the early 1980s. Since then the

market has seen phenomenal growth. Swaps now occupy a position of

central importance in the over-the-counter derivatives market.

A swap is an agreement between two companies to exchange cash flows

in the future. The agreement defines the dates when the cash flows are to

be paid and the way in which they are to be calculated. Usually the

calculation of the cash flows involves the future values of interest rates,

exchange rates, or other market variables.

A forward contract can be viewed as a simple example of a swap.

Suppose it is March 1, 2007, and a company enters into a forward

contract to buy 100 ounces of gold for $600 per ounce in one year. The

company can sell the gold in one year as soon as it is received. The

forward contract is therefore equivalent to a swap where the company

agrees that on March 1, 2008, it will pay $60,000 and receive 1005,

where S is the market price of one ounce of gold on that date.

Whereas a forward contract is equivalent to the exchange of cash flows

on just one future date, swaps typically lead to cash flow exchanges

taking place on several future dates. The most common swap is a "plain

Financial Products and How They Are Used for Hedging 37

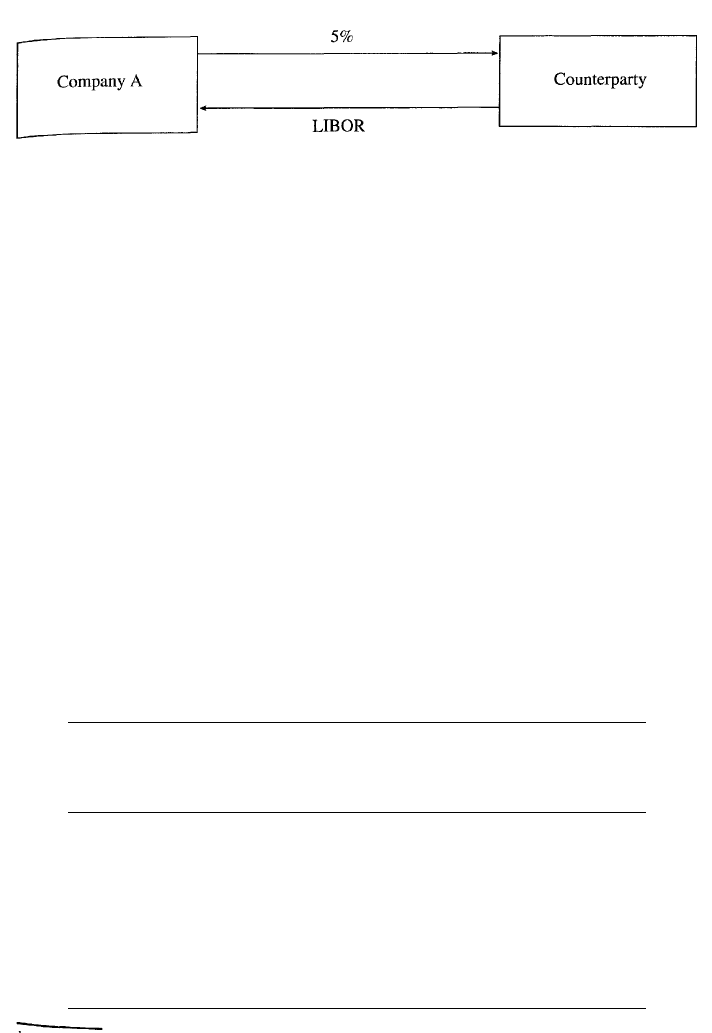

5%

Company A Counterparty

LIBOR

Figure 2.2 A plain vanilla interest rate swap.

vanilla" interest rate swap where a fixed rate of interest is exchanged for

LIBOR.

1

Both interest rates are applied to the same notional principal.

A swap where company A pays a fixed rate of interest of 5% and receives

LIBOR is shown in Figure 2.2. Suppose that in this contract interest

rates are reset every six months, the notional principal is $100 million,

and the swap lasts for three years. Table 2.4 shows the cash flows to

company A when six-month LIBOR interest rates prove to be those

shown in the second column of the table. The swap is entered into on

March 5, 2007. The six-month interest rate on that date is 4.2% per year

or 2.1 % per six months. As a result, the floating-rate cash flow received

six months later on September 5, 2007, is 0.021 x 100 or $2.1 million.

Similarly, the six month interest rate of 4.8% per annum (or 2.4% per six

months) on September 5, 2007, leads to the floating cash flow received

six months later (on March 5, 2008) being $2.4 million, and so on. The

fixed-rate cash flow paid is always $2.5 million (5% of $100 million

Table 2.4 Cash flows (millions of dollars) to company A in swap

in Figure 2.2. The swap lasts three years and has a principal of

$100 million.

Date

Mar. 5, 2007

Sept. 5, 2007

Mar. 5, 2008

Sept. 5, 2008

Mar. 5, 2009

Sept. 5, 2009

Mar. 5, 2010

6-month

LIBOR rate

(%)

4.20

4.80

5.30

5.50

5.60

5.90

6.40

Floating

cash flow

received

+2.10

+2.40

+2.65

+2.75

+2.80

+2.95

Fixed

cash flow

paid

-2.50

-2.50

-2.50

-2.50

-2.50

-2.50

Net

cash flow

-0.40

-0.10

+0.15

+0.25

+0.30

+0.45

1

LIBOR is the London Interbank Offered Rate. It is the rate at which a bank offers to

make large wholesale deposits with another bank and will be discussed in Chapter 4.

38

Chapter 2

applied to a six-month period).

2

Note that the timing of cash flows

corresponds to the usual way short-term interest rates such as LIBOR

work. The interest is observed at the beginning of the period to which it

applies and paid at the end of the period.

Plain vanilla interest rate swaps are very popular because they can be

used for many purposes. For example, the swap in Figure 2.2 could be

used by company A to transform borrowings at a floating rate of LIBOR

plus 1% to borrowings at a fixed rate of 6%. (Pay LIBOR plus 1%,

receive LIBOR, and pay 5% nets out to pay 6%.) It can also be used by

company A to transform an investment earning a fixed rate of 4.5% to an

investment earning LIBOR minus 0.5%. (Receive 4.5%, pay 5%, and

receive LIBOR nets out to receive LIBOR minus 0.5%.)

Example 2.1

Suppose a bank has floating-rate deposits and five-year fixed-rate loans. As

explained in Section 1.5, this exposes the bank to significant risks. If rates rise,

then the deposits will be rolled over at high rates and the bank's net interest

income will contract. The bank can hedge its risks by entering into the swap in

Figure 2.2 (taking the role of Company A). The swap can be viewed as

transforming the floating-rate deposits to fixed-rate deposits. (Alternatively,

it can be viewed as transforming fixed-rate loans to floating-rate loans.)

Many banks are market makers in swaps. Table 2.5 shows quotes for US

dollar swaps that might be posted by a bank.

3

The first row shows that the

Table 2.5

Maturity

(years)

2

3

4

5

7

10

Swap quotes made by a market maker

(percent per annum).

Bid

6.03

6.21

6.35

6.47

6.65

6.83

Offer

6.06

6.24

6.39

6.51

6.68

6.87

Swap rate

6.045

6.225

6.370

6.490

6.665

6.850

2

Note that we have not taken account of day count conventions, holidays, calendars,

etc., in Table 2.4.

3

The standard swap in the United States is one where fixed payments made every six

months are exchanged for floating LIBOR payments made every three months. In

Table 2.4 we assumed that fixed and floating payments are exchanged every six months.

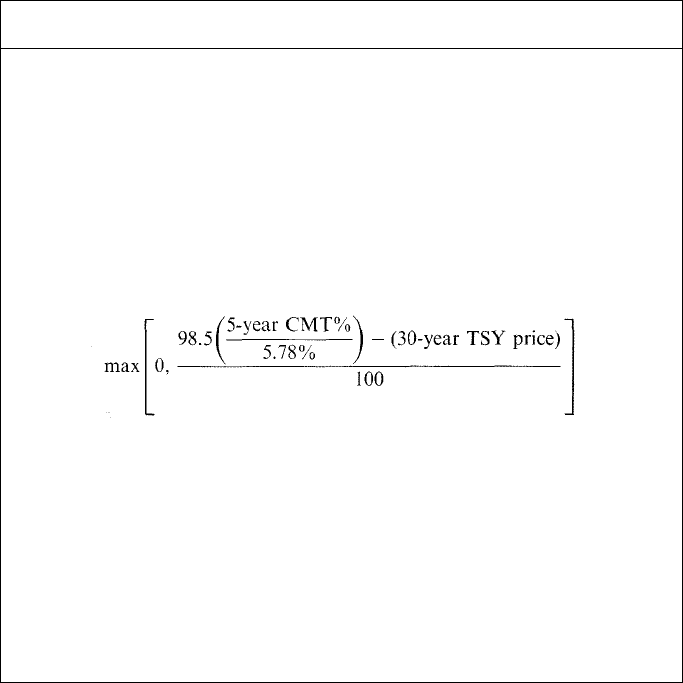

Business Snapshot 2.2 Procter and Gamble's Bizarre Deal

A particularly bizarre swap is the so-called "5/30" swap entered into between

Bankers Trust (BT) and Procter and Gamble (P&G) on November 2, 1993.

This was a five-year swap with semiannual payments. The notional principal

was $200 million. BT paid P&G 5.30% per annum. P&G paid BT the average

30-day CP (commercial paper) rate minus 75 basis points plus a spread. The

average commercial paper rate was calculated by taking observations on the

30-day commercial paper rate each day during the preceding accrual period

and averaging them.

The spread was zero for the first payment date (May 2, 1994). For the

remaining nine payment dates, it was

In this, five-year CMT is the constant maturity Treasury yield (i.e., the yield on

a five-year Treasury note, as reported by the US Federal Reserve). The 30-year

TSY price is the midpoint of the bid and offer cash bond prices for the 6.25%

Treasury bond maturing on August 2023. Note that the spread calculated from

the formula is a decimal interest rate. It is not measured in basis points. If the

formula gives 0.1 and the CP rate is 6%, the rate paid by P&G is 15.25%.

P&G was hoping that the spread would be zero and the deal would enable it

to exchange fixed-rate funding at 5.30% for funding at 75 basis points less than

the commercial paper rate. In fact, interest rates rose sharply in early 1994, bond

prices fell, and the swap proved very, very expensive. (See Problem 2.30.)

Financial Products and How They Are Used for Hedging 39

bank is prepared to enter into a two-year swap where it pays a fixed rate of

6.03% and receives LIBOR. It is also prepared to enter into a swap where it

receives 6.06% and pays LIBOR. The bid-offer spread in Table 2.5 is three

or four basis points. The average of the bid and offer fixed rates is known as

the swap rate. This is shown in the final column of the table.

The trading of swaps is facilitated by ISDA, the International Swaps

and Derivatives Association. This organization has developed standard

contracts that are widely used by market participants. Swaps can be

designed so that the periodic cash flows depend on the future value of

any well-defined variable. Swaps dependent on interest rates, exchange

rates, commodity prices, and equity indices are popular. Sometimes there

are embedded options in a swap. For example, one side might have the

option to terminate a swap early or to choose between a number of

40

Chapter 2

different ways of calculating cash flows. Occasionally swaps are traded

with payoffs that are calculated in quite bizarre ways. An example is a

deal entered into between Procter and Gamble and Bankers Trust in 1993

(see Business Snapshot 2.2). The details of this transaction are in the

public domain because it later became the subject of litigation.

4

The

valuation of swaps is discussed in Appendix B at the end of the book.

Options

Options are traded both on exchanges and in the over-the-counter

market. There are two basic types of options. A call option gives the

holder the right to buy the underlying asset by a certain date for a certain

price. A put option gives the holder the right to sell the underlying asset

by a certain date for a certain price. The price in the contract is known as

the exercise price or strike price; the date in the contract is known as the

expiration date or maturity. American options can be exercised at any time

up to the expiration date, but European options can be exercised only on

the expiration date itself.

5

Most of the options that are traded on

exchanges are American. In the exchange-traded equity option market,

one contract is usually an agreement to buy or sell 100 shares. European

options are generally easier to analyze than American options, and some

of the properties of an American option are frequently deduced from

those of its European counterpart.

An at-the-money option is an option where the strike price is close to

the price of the underlying asset. An out-of-the-money option is a call

option where the strike price is above the price of the underlying asset or

a put option where the strike price is below this price. An in-the-money

option is a call option where the strike price is below the price of the

underlying asset or a put option where the strike price is above this price.

It should be emphasized that an option gives the holder the right to do

something. The holder does not have to exercise this right. By contrast, in

a forward or futures contract, the holder is obligated to buy or sell the

underlying asset. Note that, whereas it costs nothing to enter into a

forward or futures contract, there is a cost to acquiring an option.

The largest exchange in the world for trading stock options is the

Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE; www.cboe.com). Table 2.6

4

See D.J. Smith, "Aggressive Corporate Finance: A Close Look at the Procter and

Gamble-Bankers Trust Leveraged Swap." Journal of Derivatives 4, No. 4 (Summer 1997):

67-79.

5

Note that the terms American and European do not refer to the location of the option

or the exchange. Some options trading on North American exchanges are European.