Heine Bernd, Nurse Derek. A Linguistic Geography of Africa

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

one observes an increase in head marking on the verb, e.g. bound markers for

semantic roles such as dative, instrumental, location, or direction. In Dim-

mendaal (2006) it is argued that in Nilo-Saharan groups like Nilotic and

Surmic we see a drift away from dependent marking at the clausal level as well

as a slant towards head marking on the verb. And, as argued in the same

contribution, the typological shift appears to be related historically to a shift in

constituent order, since the verbal strategy is common in Nilo-Saharan, more

specifically in Eastern Sudanic, groups which are not verb-final.

In spite of the fact that the marking of more peripheral semantic roles such

as location or instrument does not appear to be attested in the so-called verb-

final Nilo-Saharan or Afroasiatic languages, it cannot be claimed that this is a

property of verb-final languages in general. Ko

¨

hler (1981: 503) points out with

respect to the Ce ntral Khoisa n language Khoe (Kxoe) that among the many

verbal derivational markers, there is a marker -‘o expressing a directive-

inessive. The marking of direction on verbs is also attested, for example, in

Ijoid languages. Compare Izon (data from Williamson & Timitimi 1983),

which uses a directional suffix -m

o

_

with inherently intransitive verbs in order to

incorporate a notion of path or direction:

(43) ar

i

_

ki

_

mI

_

-bi

_

we

_

ni

_

-m

o

_

-mi

_

ISG man-DF walk-DIR-TA

‘I walked towards the man’

Alternatively, when the verb is already transitive, a serial verb ‘take’ is used

in order to host the original object in Izon:

(44) ar

i

_

aruu

_

-bi

_

aki

_

t

i

_

n kaka-m

o

_

-mi

_

1SG canoe-DF take tree tie-DIR-TA

‘I moored the canoe to a tree’

Table 9.3 Dependent marking in Nilo-Saharan

Language group Constituent order Periph. case* ProSu ProOb

Saharan V-final yes yes yes

Maban V-final yes yes yes

Fur V-final yes yes no

Kunama V-final yes yes yes

Eastern Sudanic

Nubian V-final yes yes no

Tama V-final yes yes no

Nyimang V-final yes no no

* Peripheral case: Dative, Instrument, Locative, Ablative, Genitive.

Gerrit J. Dimmendaal292

Accordingly, the virtual absence of this verbal strategy in Nilo-Saharan

languages with a verb- final syntax and its emergence in Nilo-Saharan groups

which are not verb-final, such as Nilotic or Surmic, is nothing but an

incidence of family-specific historical fact.

The actual system of head marking on the verb, whether involving core or

peripheral semantic roles, always depends on the specific history of a language

or language family, with internal as well as external (contact) factors deter-

mining the dir ection of change. There is thus absolutely no un iformity in this

respect between languages that may indeed be claimed to share a verb-final

syntax.

Languages putting the verb in final position may also differ considerably as

to the way in which they express complex clausal relations. Nevertheless, there

seems to be at least one non-trivial morphosy ntactic phenomenon which does

seem to be related to constituent order phenomena, namely verbal com-

pounding. This latter aspect, as argued in section 9.5, would seem to fol low

from the “self-organizing principles” of these languages. Before moving into

this common and widespread morphosyntactic property of so-called verb-final

languages, however, I will investigate one additional property of languages

with this proclaimed syntactic configuration, showing again how different such

languages can in fact be from each other from a typological point of view.

9.4 Beyond the clause level

In an important study on the structure of narrative discourse, Long acre (1990 )

has shown that African languages may differ considerably with respect to the

expression of the storyline in narrative discourse. A common pattern in so-

called verb-final languages of northeast Africa involves the use of converbs,

i.e. of morphologically reduced finite verbs occurring in dependent clauses.

Traditionally, converbs have been referred to by way of a variety of other

terms, e.g. as participles or gerunds. But these labels would seem to represent a

typical translation-oriented nomenclature rendering the pseudo-literal trans-

lation of the form into European languages, rather than recognizing its true

form and function. Crosslinguistically, converbs tend to share two important

characteristics (as established by Haspelmath & Ko

¨

nig 1995). First, such verb

forms are morphologically distinct from main verbs, which tend to carry the

maximum number of inflectional properties, or from other dependent verb

forms, e.g. those occurring in adverbial clauses. Second, the semantic range

covered by thes e converbs includes (an adverbial type of) modification, and the

expression of event sequences. These properties are illustrated mainly for

Omotic languages in table 9.4.

Omotic languages differ as to whether coreferential (logophoric) vers us

disjunctive reference marking for subjects is distinguished on converbs. In

Africa’s verb-final languages 293

Maale, where the verb has a rather reduced morphological structure compared

to most other Omotic languages, this distinction is nevertheless marked, as

shown by the following examples from Amha (2001):

(45) ?ı

´

zı

´

mi

s’-o

´

ti

k’-a

´

??o makiin-aa

3MSG:NOM tree-ABS cut-CNV car-LOC

c’aan-e

´

-ne

load-PERF-A:DECL

‘Having cut the wood, he loaded it on a car [sequential]’

(46) ?ı

´

zı

´

mı

´

s’-o

´

tı

´

k-e

´

mnu

´

u

´

nı

´

makiin-aa

3MSG:NOM wood-ABS cut-CNV 1PL:NOM car-LOC

c’aan-e

´

-ne

load-PERF-AFF:DECL

‘He having cut the wood, we loaded it on the car [disjunctive reference]’

Omotic languages differ as to whether the common distinction between

masculine and feminine gender is maintained as an inflectional property in

converbs. Wolaitta uses a suffix -a(da) on the converb when the

corresponding subj ect is feminine, and a suffix -i(di) for masculine subjects.

In Maale, only one type of marker is found, -i (historically the masculine

form) regardless of gender; Dime has generalized the feminine form, -a.

As pointed out by Van Valin & LaPolla (1997: 448), “[t]he traditional

contrast between subordination and coordination seems to be very clearcut for

languages like English and its Indo-European brethren, but when one looks

farther afield, constructions appear which do not lend themselves to this neat

division.” Unlike coordinated clauses, clauses containing a converb could not

stand on their own as independent clauses, e.g. because the latter lack a

modality marker, nor do converbs carry aspect in languages like Maale. In this

sense, converb clauses are dependent, but they are distinct from subordinate

clauses in that the latter again require aspect markers as well as specific

modality markers which are formally distinct from the indicative marker on

main verbs; in other words, both the main clause and the subordinate (adverbial)

Table 9.4 Inflection of main verbs and converbs in Omotic

Omotic Converb Main verb

Wolaitta gender þ number for subject gender þ number, aspect

Aari person þ number for subject tense, aspect, person, number

Bench tense, aspect, person þ gender for subject tense, aspect, person, gender

Maale no marking for tense, aspect, person or

gender; one marker for subject

aspect

Gerrit J. Dimmendaal294

clause may carry their own illocutionary force. Consequently, Amha (2001)

has argued in her analysis of Maale that converb constructions in this Omotic

language indeed involve a third type of nexus relation, namely co-subordi-

nation, rather than coordination or subordination.

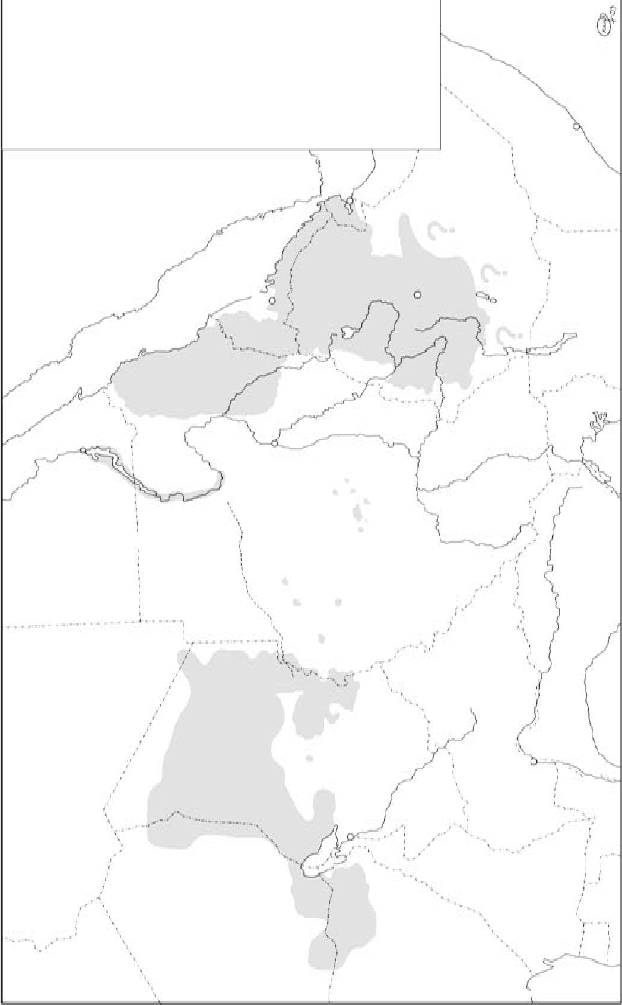

Converbs are also common in a variety of Nilo-Saharan languages (Amha

& Dimmendaal 2006a; see also map 9.2). The very same languages manifest

additional typological similarities to Afroasiatic languages in Ethiopia, such

as the common use of verb-final structures, case marking, postpositions (or

postnominal modifiers), and the frequent use of ‘say’ constructions and other

types of verbal compounding amongst others. For example, in their analysis

of the Saharan language Beria (also known as Zaghawa), Crass and Jakobi

(2000) have shown that the converb in this language represents a morpho-

logically reduced finite verb which is used in order to express a sequence of

events.

(47) a

´

I ba

´

ga

´

ra

´

e

´

g

in

O

Og- ge¯n

ir _u

´

gı

´

1SG friend my visit:1SG-CNV village:DAT/LOC go:1SG:PERF

‘I went (in)to the village to visit my friend’

Clauses with converbs usually are part of a continuum involving dependency

relations, with subordination on the one hand, and coordination at the other end

of the continuum. This may be further illustrated with examples from the

Omotic language Wolaitta, which uses a distinct set of suffixes on verbs,

reflecting different degrees of cohesion between the clause containing the verb

and the main clause (see table 9.5).

The short forms -a and -i in Wolaitta occur as optional variants of the converb

markers -ada and -idi. However, with lexicalized compounds in Wolaitta, i.e.

with idiomatic converb plus main verb constructions, the short variants are

obligatory; lexical compounding in Wolaitta and other languages in the area is

further discussed below in section 9.5. (For a more detailed account of verbal

compounding and converb constructions in Wolaitta and other languages in

northeastern Africa, see Amha & Dimmendaal 2006b.)

Examples illustrating the use of these markers:

(48) ?a

´

na-at-a kaass -a

´

da

´

zin?-is-ausu

3FSG:NOM child-PL-ABS play:TR-CNV lie down-CA

US-3F:SG:IPERF

‘She brings the children to bed after having played with them’

(49) ?a

´

na-at-a kaass -ı

´

dı

´

zin?-is-iisi

3MSG:NOM child-PL-ABS play:TR-CNV lie down-CAUS-

3MSG:PERF

‘He brought the childr en to bed after having played with them’

Africa’s verb-final languages 295

Afroasiatic

Nilo-Saharan

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

Beja

Bilin

Tigrinya

Afar

Amharic

Oromo

Harari

Gurage

Awngi

Wolaitta

Maale

Aari

Bench

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

Kunama

Nara

Dongolese Nubian

Nyimang

Hill Nubian

Midob

Birked

Ta ma

Masalit

Beria

Teda-Daza

Kanuri

25

24

23

22

21

19

20

17

18

6

5

5

6

9

3

4

14

15

2

1

16

13

8

7

10

12

11

Bangui

Congo

Ubangi

C

hari

Lake Albert

Lake Kyoga

Lake Turkana

Mogadishu

Addis Ababa

Khartoum

Asmara

Lake

Abaya

Lake

Ta na

Omo

White Nile

Blue Nile

N'Djamena

Lake Chad

W

a

d

i

H

o

w

a

r

N

i

l

e

A

t

b

a

r

a

R

E

D

S

E

A

Djibouti

Lake Nasser

Assuan

Map 9.2 Languages with converbs in northeastern and north-central Africa

296

As shown by these examples, converb constructions are commonly used in

order to expre ss a sequence of actions. A distinct set of (gender-sensitive)

markers are used in Wolaitta in order to express simultaneous events. There are

two types of simultaneous clauses: “same-subject simultaneous clauses” and

“different-subject-simultaneous clauses.” In same-subject simultaneous clau-

ses, the subject of the dependent verb and that of the main verb are

coreferential with each other.

(50) ?as-at-ı

´

harg-iı

´

ddı

´

?oott-o

´

son

person-PL-PL:NOM be sick-SIM:PL work-3PL:IPF

‘The people work while they are sick’

(51) mi

R

ir-ı

´

ya

´

ka

´

tta gaac’c’-aı

´

dda

´

yet’t’-ausu

woman-F:NOM grain:ABS grind-SIM:F sing-3FSG:IPF

‘The woman sings while grinding grain’

The converb in these examples shows agreement with the subject, which is its

obligatory controller (i. e. the same-subject converb cannot take its own sub-

ject). By contrast, example (52) contains a clause (‘while the woman grinds

grain’) which is more adverbia l in nature. Unlike the dependent verb in same-

subject simultaneous clauses such as (51), it has its own overt (disjunct)

subject, itself non-coreferential with the subject of the main verb. This latter

feature is also reflected in the fact that gender distinctions between masculine

and feminine subjects in the respective clauses are not expressed, i.e. the

simultaneous event markers are invariable.

(52) mi

R

ir-ı

´

ya

´

ka

´

tta gaac’c’-ı

´

R

in bitan-ee k’er-eesi

woman-F:NOM grain:ABS grind-SIM man-M:NOM wood:ABS

mı

´

tta

split-3MSG:IPF

‘The man splits wood while the woman grinds grain’

Example (53) contains a verbal suffix -ı

´

n(i) indicating temporal adverbial

clauses; this latter type often corresponding to causal clauses in English.

Table 9.5 Clausal cohesion markers in Wolaitta

Feminine Masculine

lexicalized converb plus main

verb constructions

-a -i

freely generated converb constructions -ada -idi

simultaneous clauses with coreference -aı

´

dda

´

-iı

´

ddı

´

simultaneous clauses with switch

reference

-ı

´

R

in(i)

temporal/causal clauses -ı

´

n(i)

Africa’s verb-final languages 297

(53) ta

´

a

´

nı

´

ku

´

nd-ı

´

ni ?ı

´

ta

´

na

´

dent-iı

´

si

1SG:NOM fall-DS:CNV 3MSG :NOM 1SG:O raise-3MSG.PERF

‘I having fallen, he helped me to stand up’

Adverbial clauses in Wolaitta of the type above are in paradigmatic contrast

with other clausal types, e.g. those expressing condi tion:

(54) mi

R

ir-ı

´

y ka

´

tta gaac’c’-ı

´

kko bitan-ee mı

´

tta

grain:ABS grind-CND man-M:NOM wood:ABS woman-F:NOM

k’er-eesi

split-3MSG:IPERF

‘If the woman grinds grain, the man splits wood’

Whereas verb conca tenation or serialization as such is also common in Central

Khoisan languages, it would seem that from a typological point of view this

strategy is to be distinguished from the converb plus main verb construction

illustrated for Wolaitt a above, itself characteristic of a variety of Afroasiatic

and Nilo-Saharan languages in the area. Contrary to Omotic and other north-

east African languages, there appears to be no formal indexing for conjunct ive

versus disjunctive reference between subjects of dependent versus main

clauses in Central Khoisan; moreover, switch reference as found in these

Afroasiatic and Nilo-Saharan languages, does not appear to be a part of the

verb concatenation system in Central Khoisan languages, as shown next.

In his description of the Central Khoisan language kAni, Heine (1999: 77)

uses the label “converb” with quotation marks in reference to specific reduced

clauses headed by a marker ko or yo. From the examples presented by Heine

(1999:77–9) it would seem that the distributional and functional properties of

constructions with such markers in kAni are indeed rather different from

converbs in Afroasiatic or Nilo-Saharan languages. Firstly, in all cases in kAni

coreference appears to be involved. Second, the so-called converb may als o co-

occur with verbs in main clauses apparently, e.g. im perative verb forms. Third,

the use of these particles occurs next to a strategy whereby a sequencing of

events is expressed without the obligatory use of either of these markers, as

shown by the narrative discourse text (Heine 1999: 87–111).

(55) —x’oa- ra ko kun

go.out-II CONV go

‘Go away!’

In kAni, the so-called conver b marker is apparent ly a free morpheme, which

need not be adjacent to the verb with which it co-occurs.

10

Verb concatenation or serialization is a characteristic property of Central

Khoisan languages in general. One of the most detailed analyses of clause

chaining in such a language is Kilian-Hatz (2006) on Khoe. As shown by the

Gerrit J. Dimmendaal298

author, there are different degrees of interlacing between clauses in this

Central Khoisan language, manifested in the degree of independent reference in

terms of tense, aspect, negation, modality, subject, or object marking. Tense,

aspect, mood as well as negation is suffixed to the last verb (verbs may not be

separately marked for TAM). Note also that the object may follow the verbal

complex.

(56) tı

´

k’a

´

m

´

-a

´

jx’

~

u-

˛ya-a

´

-te

`

co

´

ro

`

-h

E

E

1SG beat-II kill-NEG-I-

PRES

monitor-

3FSG

O

‘I don’t beat the monitor to death’

Verbs may not be separately passivized in Khoe, the passive marker being

suffixed to the last verb. Also, tran sitive verbs may share the direct object role

or have dif ferent objects, and the verbs are or are not contiguous. With same

object constructions the object precedes or follows the verbal complex.

Verb serialization in languages like Khoe appears to cover a range of event

structures. Semantically, such additional verbs may serve to express manner,

movement (‘come, arrive’), as well as position (‘stand’, ‘sit’, ‘lie’). In addition,

the Akt ionsart of a verb may be modified this way, e.g. in order to express a

continuous, proxi mative (‘be about to’), or inchoative meaning. In contrast to

the converb constructions of Afroasiatic and Nilo-Saharan languages dis-

cussed above, such concatenations of verbs in Khoe do not inflect for person.

Compare again the the following examples from Kilian-Hatz (2006):

(57) xa

`

ma

´

t- ga

`

ra

`

-a

´

-te

`

tha

´

ma

`

3MSG stand-II write-I-PRES letter O

‘He writes a letter in standing’

(58) xa

`

ma

´

kya

˜

ı˜-a ka

´

m-a

`

-te

`

3MSG be.nice-II feel-I-PRES

‘He feels well’

(59) c

~

u

~

u-a n—u

˜

-a-xu-cu

`

hurry-II sit.down-II-COMP-2FSGVOC

‘Sit down quickly!’

Comparative constructions are also rendered through the same strategy of verb

serialization in Khoe. Whereas in the northeastern African region compara-

tives tend to be formed by way of a separate (similative) case marking, Khoe

uses the more com mon African pattern, by way of the verb ‘sur pass,’ n

g

yxu

(or, alternatively, the verb ‘overpower,’ n

go

´

ngoe

)

(60) kg

E-kho

`

e

`

-djı

`

ji

-e

`

-ko

`

e

`

kx’a

´

-kho

`

e

`

-ku

`

a

`

a

´

ngyxu-a

female-person-3FPL sing-I-HAB male-person-3MPL O surpass-II

‘Women sing better than men’

Africa’s verb-final languages 299

Treis (2000) also presents a classificat ion of complex sentence structures in the

Central Khoisan language Khoe, focusing on the dependency marking mor-

phemes -ko and no, and using a variety of criteria, such as the occurrence of

independent subject and object reference, and the use of independent operators

such as tense–aspect, modality, illocutionary force, and negation in the clauses

together forming a complex sentence. The author uses a framework inspired by

Role and Reference Grammar (Van Valin & LaPolla 1997), thereby distin-

guishing between different types of junctures, e.g. nucleus and core. On the

basis of a careful screening of the various criteria listed above, Treis (2000: 93)

concludes that complex clauses with -ko

´

mainly, but not exclusively, belong to

the nucleus juncture type, i.e. to a construction type in which core arguments

are shared:

(61) kx’e

´

i

ti

j’e

´

’a

`

kgu

`

-a

´

-xu-a

`

-ko

`

njgo

´

a

´

-a

`

-go

`

e

`

first 1SG fire O light-II-COMP-II-CONV cook-I-FUT

kx’o

´

xo

`

’a

`

meat O

‘First I will light the fire, and then I will cook meat’

In a minority case, core juncture, characterized by independent argument

reference, is involved. Clauses involving the conjunction no on the other hand

represent a looser type of complex clause formation in Khoe, involving core

juncture; in the latter case, each of the clauses may itself contain a nucleus

juncture, as in the following example (Treis 2000: 94):

(62) wa

´

mda-ma

`

kya

˜

~

a-ko

´

k

~

uu

˜

no

`

xa

`

ma

´

xa

`

va

´

na

springhare-2MSG run-CONV go CONJ 3MSG again

xa

`

ma

´

khe

´

i

3MSG pull

‘When the springhare moves, he pulls [again]’

According to Treis (2000: 62), the marker -ko

`

in Khoe is used primarily with

same-subject constructions. However, the same formative is compatibl e with

different subject constructions, as attested through a number of examples.

What appears to be crucial to the Central Khoisan system, however, is adja-

cency of the two verbs. The explicit crossreferencing system in Omot ic lan-

guages would seem to make such a condition super fluous in this latter genetic

grouping. Interestingly, however, whenever verbs are adjacent in languages

from the various genetic groupings discussed here, they start to interact

semantically, leading to verbal compounding and to lexicalization and idio-

mati cization, as show n in section 9. 5 below.

In languages discussed in this chapter, the categorial distinction betwee n

nouns and verbs is usually evident on distributional as well as on formal

(morphological) grounds.

11

Thus, in a prototypical Omotic language the finite

Gerrit J. Dimmendaal300

verb is inflected for tense, aspect, negation, and modality, whereas a noun is

inflected for gender, number, case, and definiteness, although not all of these

inflectional features are necessarily pres ent in all forms at all times. At the

same time, one may observe a transgression of these categorial boundaries

under specific syntactic and semantic conditions, in that verbs may take spe-

cific peripheral case markers such as the dative. This property is best known

from Omotic and Cushitic languages. (We do not know at present whether the

same property is attested in any of the Nilo-Saharan languages discussed

above.) Compare the following example from Maale (Amha 2001: 186):

(63) ?i

i

ni

[?i

za

´

?am?o

´

R

anc-o

´

-m]

3MSG:NOM 3FSG:NOM coffee:ABS sell-ABS-DAT

bookk-o

´

da

´

kk-e

´

-ne

market-ABS send-PERF-AFF:DECL

‘He sent her to the market to sell coffee’

In order to express a purpos ive meaning, Maale uses a dative case marker. As

the purposive clause involves a verb, and as dependent clauses in Maale are

always verb-final, the case marker is attached to this final constituent as a

phrasal affix; the absolutive case marker is present as well, as peripheral case

markers such as the dative, locative, or instrumental are always based on the

absolutive form in Maale.

The presence of case markers in the Afroasiatic and Nilo-Saharan languages

discussed here expressing these types of symbolic relations makes the use of

conjunctions or other devices for the expression of complex clause relations, as

attested in Ijoid or Central Khoisan languages, superfluous.

9.5 Below the clause level: the role of

self-organizing principles

According to Greenberg (1963), verb-final languages tend to be predominantly

suffixing, rather than prefixing. This property is indeed common in Omotic

languages, which, as we saw above, are probably the best representatives of

modifier–head languages, on the Af rican continent, with both derivational and

inflectional suffixes following the root. But the picture is far more diverse in

other African language groups with a predominantly verb-final constituent

order; in Nilo-Saharan, for example, verbal prefixes marking pronominal

subjects or causatives are common. But there is one morphosyntactic property

which does seem to emerge independently in these languages, namely verb

compounding.

As pointed out by Westermann (1911: 61) in his survey of “Sudanic”

languages, it is common in, for example, Nubian (now classified as Nilo-

Saharan) to concatenate verbs or verbal roots as a lexical process, resulting

Africa’s verb-final languages 301