Fouracre P. The New Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. 1: c. 500-c. 700

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The earliest Anglo-Saxon kingdoms 273

Most sixth-century graves contained grave-goods of some sort and, until

the later part of the century, the richest graves arguably represent merely the

top end of what was a broad continuum of burial wealth;

42

most attempts to

rank graves of this period according to burial wealth have produced spurious

results. Where burial plots can be identified, it is unusual to find one which was

markedly poorer in burial wealth than other, broadly contemporary plots.

43

If

these plots do represent households, as seems likely, this suggests that ranking

was expressed primarily within households rather than between them, a thesis

supported by the evidence from settlements (see below). At the sixth-century

cemetery at Norton-on-Tees, for example, the roughly equal numbers of male

weapon graves and well-equipped females (approximately a dozen of each)

suggest four ‘leading’ couples over three generations, at the heads of four

households, each consisting of nine or ten individuals.

44

Written sources leave little doubt that kinship played a central role in defin-

ing early Anglo-Saxon communities, and suggest that it was essentially bilateral

(i.e. no distinction was made between relatives on the mother’s and father’s

side), virilocal and exogamous (i.e. the individual was required to marry outside

of his/her own kindred and most females moved to live with their husband’s

kin).

45

Social and legal status were, in part, determined by one’s membership of

a particular kin group, which offered protection as well as access to resources.

46

Yet, while it may be possible to identify the heads of households in cemeter-

ies, identifying whole kin groups or households with any certainty is extremely

problematic. It nevertheless seems reasonable to suppose that a cluster of graves

with a shared orientation or focus (for example around a central burial) are

those of individuals who were in some way affiliated in life. At the cemetery

of Berinsfield, for example, the distribution of certain epigenetic traits (such

as dental anomalies, or the occurrence of sixth lumbar vertebrae), which are

probable indicators of genetic links, as well as the distribution of men, women

and children, support the theory that the different sectors of the cemetery

represent distinct households.

47

Settlements

Since the 1970s, a few settlements have been excavated on a sufficiently large

scale to provide a reasonably clear picture of what a sixth-century village or

42

SeeShepherd (1979).

43

See, for example, the cemeteries at Berinsfield, Oxon., Norton, Cleveland, and Apple Down, Sussex.

Down and Welch (1990), figs. 2.8 and 2.9;Sherlock and Welch (1992), figs. 21 and 24;Boyle et al.

(1995), p. 133 and fig. 30;H

¨

arke (1997), p. 138.

44

Sherlock and Welch (1992), p. 102.

45

H

¨

arke (1997), p. 137.

46

Charles-Edwards (1997).

47

Boyle et al. (1995).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

274 helena hamerow

hamlet looked like. While their variability in size and layout has made even

the use of the term ‘village’ a contentious matter, most shared certain general

characteristics. First, they were relatively small (corresponding in size with the

populations indicated in inhumation and mixed-rite cemeteries) and closely

spaced. In some regions where intensive archaeological survey and/or exca-

vation have been carried out, such as the terrace gravels of the upper and

lower Thames valley, early Anglo-Saxon settlements occur at remarkably close

intervals of around 2 to 5 kilometres.

48

The Anglo-Saxon settlement at Mucking, on a gravel terrace overlooking

the Thames estuary in Essex, remains the most extensively excavated Anglo-

Saxon settlement published to date.

49

Here, some 14 hectares of land were

investigated by archaeologists in the 1960s and 1970s, in the course of which

over fifty timber buildings and over 200 sunken huts were uncovered. Not all

of these buildings were occupied at the same time, however. The focus of the

settlement shifted over nearly a kilometre in the course of some 250–300 years.

The very large number of buildings uncovered thus represents on average only

around ten household units at any one time, corresponding broadly to the

population size indicated by the two contemporary cemeteries excavated at

Mucking. There is growing evidence to suggest that such shifting settlement

was widespread in the sixth century.

50

A third characteristic shared by most sixth-century settlements, and exem-

plified by Mucking as well as West Stow, in Suffolk,

51

is a lack of obvious edges,

boundaries or other signs of planning, whether communal or imposed, such as

shared trackways, enclosed groups of buildings indicating farmsteads or prop-

erties, or an obvious focal or central building or feature. Occasionally traces of

fences are found,

52

but virtually none of the more substantial enclosures found

so far can be dated earlier than the late sixth or early seventh century. While

groupings or clusters of buildings are not uncommon, and most buildings

shared a broadly east–west alignment, they do not display a clearly planned

arrangement, for example around a courtyard, and one can therefore rarely be

certain that they were contemporary.

48

SeeHamerow (1993), fig. 52;Blair (1994), figs. 16 and 24.

49

SeeHamerow (1993). The settlement at West Heslerton in the Vale of Pickering has also been

excavated on a large scale and will, when published, contribute greatly to our understanding of

settlement in this region. Interim reports suggest that it differed considerably in layout from what

we have come to expect from settlements in southern and eastern England. See Powlesland et al.

(1986) and Powlesland (1997).

50

SeeHamerow (1991) and (1992).

51

See West (1986).

52

For example at Bishopstone, Sussex, and Mucking, Essex. See Welch (1992), fig. 16 and Hamerow

(1993). At Pennyland, near Milton Keynes, and at West Stow, enclosures did not appear until the

late sixth century at the earliest. See West (1986) and Williams (1993).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The earliest Anglo-Saxon kingdoms 275

To wards the end of the sixth century, however, a number of settlements

appear in the archaeological record with clearly planned layouts and substantial

enclosures demarcating properties or households. The earliest dated examples

of these characteristics, which became much more marked in the seventh

century, are found at the settlements of Yeavering, Northumberland (a royal

vill of King Edwin)

53

and Cowdery’s Down, Hants. Despite the geographical

distance which separates them, these settlements displayed planned layouts

containing strikingly similar elements, including alignments of two or more

buildings, and rectangular fenced enclosures within which buildings (access

to which was thus controlled) were arranged in a perpendicular fashion, with

another building adjoining or leading into the enclosure.

54

The evidence that remains of sixth-century buildings reveals relatively lit-

tle variation in form or size, although archaeologists are left with little more

than ground plans (often incomplete) to ponder; much above-ground vari-

ability may of course have existed. A study of these ground plans reveals that

standard building ‘templates’ or modules were used in the construction of at

least some of these buildings. This is apparent in the striking correlations that

exist in dimensions and layout, even when comparing English and continental

buildings, suggesting a widespread and long-lived north-west European timber

building tradition.

55

How the one- or two-roomed Anglo-Saxon house was actually used, how-

ever, is far from clear. It may be that functions such as cooking and storage were

sited in separate buildings, as was the case by the tenth century to judge from

law-codes and other documents.

56

It is, nevertheless, curious that so few exam-

ples can be found of hearths in Anglo-Saxon buildings, given their prominence

in written sources,

57

though this may be due in many cases to poor conditions

of preservation.

58

To wards the end of the sixth century and the beginning of the seventh

century, several architectural innovations were introduced. The first and most

common was the use of foundation trenches into which the wall timbers were

set, a practice that became widespread in the course of the seventh and eighth

centuries.

59

Perhaps the most striking change, however, was the construction

of a small number of exceptionally large buildings (i.e. with floor areas greater

than 150 square metres) beginning around 600.Afew of these larger buildings

53

HE ii.14.

54

SeeHope-Taylor (1977), Millett with James (1984) and O’Brien and Miket (1991). It may be that the

settlement of Chalton, Hants, which displayed a similar layout, was established in the sixth century,

although its date and status are less certain. See Addyman (1972).

55

SeeZimmermann (1988) and Tummuscheit (1995), Abb. 66, 94, 95.

56

See D

¨

olling (1958), pp. 55ff.

57

Most famously in Bede, HE ii.13.

58

SeeHamerow (1999).

59

SeeMarshall and Marshall (1994) and Hamerow (1999).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

276 helena hamerow

were constructed with annexes at one or both of the gable ends but the ‘annexed

hall’ had largely disappeared by the eighth century.

A period of transition?

The cemeteries and settlements of the sixth century thus indicate that the soci-

ety within which the Anglo-Saxon identity developed was not rigidly stratified

and that high-ranking individuals were integrated within the community, in

death as well as in life. Access to power and wealth was not primarily deter-

mined by birth, and rank was dependent in large part upon factors such as

age, gender, descent and the ability to amass portable wealth, although con-

trol over land presumably also played a role (as we shall see later). Certainly,

most cemeteries of this period contain burials which are markedly richer in

grave-goods than the rest,

60

yet these are most readily interpreted as leading

individuals within the local community – heads of households or kin groups,

or of some other form of moiety – rather than members of dynasties with

supra-local authority.

61

While it is certainly possible that some families man-

aged to maintain pre-eminence over several generations, this would only have

been possible through the investment of hard-won portable wealth in expen-

sive displays such as feasting, or burial with ostentatious grave-goods. The fact

that the great variability apparent in burial wealth is not obviously reflected in

settlements supports the theory that ranking was contained for the most part

within, rather than between, households.

Hints of a change to this general pattern began to appear in the later sixth

century. The appearance of the first burial mounds, or barrows, is the most

striking of these. The first Anglo-Saxon barrows appeared some time in the mid

to late sixth century, and occur within flat-grave cemeteries. By the early part of

the seventh century, whole cemeteries consisting largely or entirely of barrows

were established in some regions, as were a few isolated, exceptionally rich,

barrows.

62

Analysis of their contents suggests that their introduction marks the

imposition of greater ‘constraints...ontheattainment of positions of rank’,

although not until the isolated barrows of the seventh century is a pre-eminent

group visible, whose status was presumably ascribed rather than achieved.

63

The use, for the first time in the post-Roman period, of a monumental burial

60

For example Grave 18 at Lechlade, Glos. See Boyle et al. (1998), figs. 5.43–7.

61

Scull (1993), p. 73.

62

SeeShepherd (1979); see also Struth and Eagles (1999).

63

SeeShepherd (1979), p. 70.Inthe seventh century, weapon burial seems increasingly to denote

membership of a narrow, elevated social rank rather than of a broad ethnic group. Thus, while the

percentage of the ‘top’ group (i.e. those buried with a sword, an axe or a seaxe) remained the same

at around 6 per cent, the ‘intermediate’ group dropped from 43 to 17 per cent, while the number of

males buried without weapons rose from 52 to 77 per cent. See H

¨

arke (1998), p. 45.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The earliest Anglo-Saxon kingdoms 277

rite appears to mark the emergence of a more regulated, closed system of

ranking in response to the increased competition for resources and the social

instability to which this competition gave rise. Burial mounds would also have

been a visible means by which a descent group established ties to its ancestors

and staked a claim to territory.

64

The appearance in some cremation cemeteries of well-furnished inhuma-

tions in the mid- to late sixth century may also be significant. The clearest

example of this is a group of fifty-seven inhumations at Spong Hill lying at

the north-eastern edge of the cremation cemetery.

65

These included a chamber

grave and four or five barrows, leading to the suggestion that these burials

represent an ascendant group who moved to the area in the sixth century and

established a near-separate, elite cemetery.

66

The fact that these inhumations

represent only one episode in the use of the cemetery (the latest burials are

cremations which post-date the inhumations) indicates that the group’s descen-

dants either became assimilated with the rest of the community or, as seems

more likely, founded a new burial ground elsewhere.

At the cemetery at Snape in Suffolk, some 18 kilometres from the presumed

royal burial ground at Sutton Hoo, a distinctive group of inhumations also

appeared in the sixth century. Snape appears to have been established in the

fifth or early sixth century essentially as a small cremation cemetery; in the

mid to late sixth century, a number of individuals were inhumed (although

these were scattered among the cremations and did not form a separate zone

as at Spong Hill), some with high-status grave-goods.

67

At least nine were

originally buried beneath barrows, one of which was exceptionally rich and

buried in a boat. In one of the flat graves, the body was buried in a log-boat

and accompanied by a pair of drinking horns, while several others contained

what appear to have been parts of real or model boats. The rite of burial in

boats is associated with elite groups in Sweden at this period; perhaps these

burials mark an ascendant lineage seeking to assert its prestigious Scandinavian

connections by adopting a distinctive rite.

68

The second half of the sixth century also saw the replacement of Salin’s

Style i,azoomorphic decoration found widely on ornamental metalwork of

the later fifth and first half of the sixth century, with Style ii,amore sinuous

form of animal interlace which, like Style i, originated in Scandinavia. This

64

SeeShepherd (1979), p. 77; also van de Noort (1993).

65

Hills et al. (1984).

66

Scull (1993). The distinction between the cremating and inhuming groups at Spong Hill is, however,

far from clear-cut. See Hills (1999).

67

Filmer-Sankey (1992), pp. 39–52.

68

Other examples of early cremation cemeteries with later inhumations of the late sixth or seventh

centuries include Caistor-by-Norwich and Castle Acre, both in Norfolk. See Myres and Green (1973),

pp. 171–2;C.Scull, pers. comm.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

278 helena hamerow

may also have a bearing on the question of social change, as Style ii was

restricted almost exclusively to prestigious metalwork (most famously, a range

of gold objects from Sutton Hoo) and manuscripts.

69

A detailed study of Style

ii motifs and the contexts of Style ii objects in Scandinavia suggests that it was

introduced in a context of political conflict and was used in public rituals (of

which burial was one) as a form of heraldic propaganda by a newly powerful

‘class’ seeking to establish itself.

70

Regrettably, Style ii objects in England are

too few and their contexts in many cases too uncertain for this to be anything

more than a tantalising possibility here.

71

Female dress, at least of the elite, was transformed in the seventh century,

when the peplos-style dress fastened at the shoulder with large, heavy brooches

was replaced by a sewn costume adorned with delicate pins and necklaces in

imitation of Mediterranean fashions. This was preceded by the appearance in

the late sixth century of brooches, which may reflect a new emphasis on ‘badges’

of high rank.

72

This is clearest in Anglian regions, with the appearance of larger,

highly ornate, so-called ‘florid’ variants of older forms, notably of cruciform

and greatsquare-headed brooches. Furthermore, stylistic analysis suggests some

degree of centralised control over the production of these brooches. Square-

headed broochesin particular are found in graves of above-average burial wealth

and may have served as a means of displaying the status of leading families.

73

As for settlements, a sufficient number of radiocarbon dates is now avail-

able to suggest that the appearance of large buildings, separate, high-status

settlements and planned layouts which made use of enclosures and trackways

were all introduced in the course of the later sixth and early seventh centuries

(see above). The interpretation of these phenomena and how they may have

been related is, however, far from clear-cut. The great halls, with their lav-

ish consumption of timber and labour, can be uncontroversially interpreted

as the homesteads of ‘central people’: new landlords who established separate

settlements and displayed an ostentatious style of building set within a dis-

tinctive layout. But while both Yeavering and Cowdery’s Down were founded

in the late sixth century, it was not until the seventh century that they took

on obviously high-status characteristics, although both made use of alignment

and enclosures from the outset. Finally, while in the case of Yeavering and

Cowdery’s Down their carefully planned layouts and use of enclosures clearly

reflect a desire to impress and to restrict access to special buildings and zones,

69

SeeSpeake (1980) and Høilund Nielsen (1997).

70

See Høilund Nielsen (1997) and Hines (1998), p. 309.

71

See Høilund Nielsen (1999).

72

SeeHawkes and Meaney (1970).

73

C. Mortimer, pers. comm.; Hines (1984), pp. 30–1 and (1998), p. 34.Inthe ‘Saxon’ area of the Upper

Thames valley, too, cast saucer brooches, in use since the fifth century, became larger towards the

end of the sixth and in the early seventh centuries. See Dickinson (1993), p. 39.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The earliest Anglo-Saxon kingdoms 279

planning need not invariably imply high status. The settlements at Pennyland

(Buckinghamshire), Riby Cross-Roads (Lincolnshire), Thirlings (Northum-

berland) and Catholme (Staffordshire) contained neither large buildings nor

exceptionally rich material culture (although none was completely excavated),

yetbythe late sixth or early seventh century all made use of track- or droveways

and fenced enclosures around buildings and paddocks.

74

The mid to late sixth century also saw the appearance of the first standard-

ised post-Roman pottery to be produced, if not on a large scale at least on

a larger scale than early Anglo-Saxon pottery generally. In the fifth and sixth

centuries, pottery was hand-made and highly variable, to the extent that it is

virtually impossible to find two vessels that are identical in form and decora-

tion, though similar motifs and stamps recur widely. Yet sherds from some 200

vessels (obviously representing only a fraction of the original number of ves-

sels produced) have been found distributed across around a dozen settlements

and cemeteries which, though they were hand-made in the same tradition as

other pottery of the period, were decorated using a distinctive, standardised

range of motifs and stamps.

75

This so-called Illington-Lackford pottery was

distributed within a small region (some 900 square kilometres) of East Anglia,

bounded by three early medieval linear earthworks. That these vessels derive

from a centre of production somewhere in the Little Ouse valley remains no

more than a theory, and the mechanism by which they were distributed is

unclear. Yet, whether their circulation was governed by gift exchange, trade

or redistribution by a local leader, the thesis that they were ‘used to maintain

relations with neighbouring political units controlling the trade routes along

the Icknield Way’ is plausible and significant.

76

Should we see a concatenation in these diverse developments in burial rite,

settlements and pottery production? Are they reflections of the same phe-

nomenon and an indication, however oblique, that conditions were right for

the emergence of ‘a conscious common English identity’?

77

It is important to

note at this point that, outside the Anglian regions, the impression of wide-

ranging social change is less clear; well-furnished burials, for example, remained

relatively common in Kent well into the seventh century, and nowhere outside

East Anglia is there an equivalent of Illington-Lackford Ware.

78

Furthermore,

74

See O’Brien and Miket (1991), Williams (1993), Steedman (1995) and Kinsley (2002).

75

SeeRussel (1984), pp. 525ff.

76

SeeRussel (1984), p. 528.See also Williams and Vince (1998)regarding pottery, some of which appears

to be early, manufactured in the Charnwood Forest region of north Leicestershire and distributed

throughout the east and north-east Midlands, and occasionally even further afield.

77

SeeHines (1995), p. 83.

78

A number of other supposed ‘workshops’ have been identified, but only Illington-Lackford pottery

has been found in sufficient quantity to suggest quasi-‘mass’ production. See Myres (1977).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

280 helena hamerow

because of the crudeness of archaeological dating, what may look like a sud-

den change in the archaeological record could in reality have spanned several

generations. Finally, because of the small number of archaeological examples

and the difficulty in dating what are effectively ‘prehistoric’ developments with

the precision demanded of historic periods, it is impossible even to be cer-

tain whether these phenomena were contemporary and may therefore be seen

as a prelude to the more widespread and obvious changes in burial practices

and settlements attributable to the seventh century, such as the appearance of

‘princely’ graves and royal vills.

79

This alone should warn us against seeking

a single, teleological explanation for these changes, and attributing them to

a far-reaching, gradual and inevitable process of kingdom formation. Change

was surely neither steady nor revolutionary, but rather sporadic and contin-

gent, playing itself out in different ways in different regions, a matter in large

part of the timing of particular, mostly unrecorded, events. The concept of

‘transitional’ periods in history has been challenged, and rightly so,

80

yet there

is a consistency to these developments which suggests they are more than an

illusion created by the nebulous light cast by seventh-century sources onto the

late sixth century.

the sixth century and kingdom formation

Oneofthe difficulties of dealing with archaeological evidence in the absence

of written sources is distinguishing the common causes behind the develop-

ments outlined above, in settlement, burial rites and material culture. To do

this, the archaeological evidence has to be considered in light of the political

and military manoeuvring detailed in later written sources. In addition, having

reviewed what is known of social structures within sixth-century communi-

ties, it remains to consider the role of relations between those communities in

kingdom formation, relations seen most clearly in the evidence for trade and

exchange.

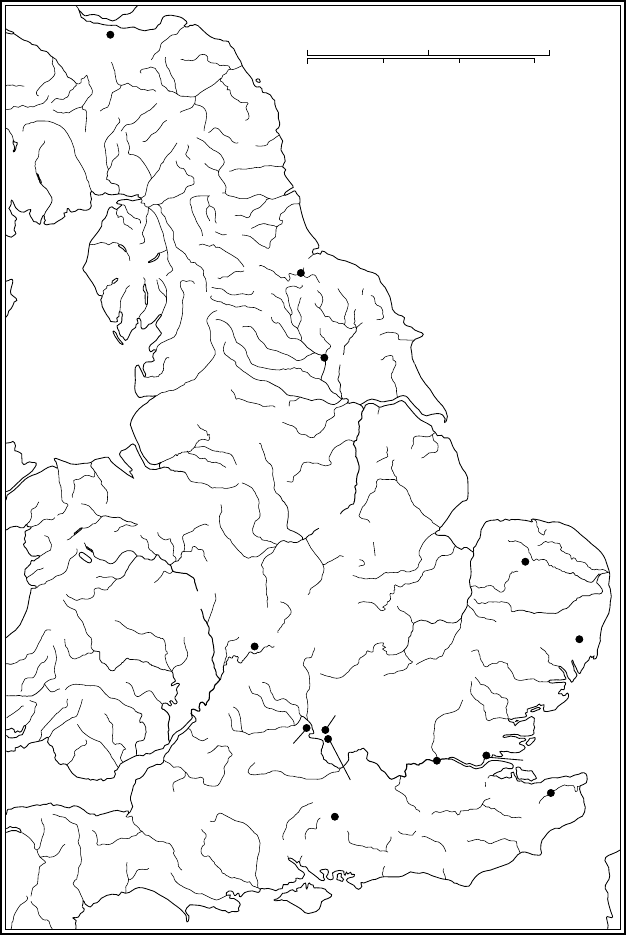

First, however, it is useful to remind ourselves that in addition to the major

kingdoms named in the written sources of the seventh and eighth centuries –

Kent, East and Middle Anglia, Lindsey, Deira, Bernicia, Mercia, Sussex,

Wessex, Essex – there were several smaller kingdoms (see Map 8).

81

The most

widely accepted theory of how these kingdoms came into being has as its cen-

tral feature territorial conquest. The fluid nature of early Anglo-Saxon social

structure provided considerable scope for ambitious individuals to gain rank

79

Some of the most famous of these ‘princely’ graves are at Sutton Hoo, Suffolk, and Asthall, Oxon.

See Carver (1992) and Dickinson and Speake (1992). See also Boddington (1990) and Geake (1997).

80

SeeHalsall (1995).

81

See Yorke (1990), map 1.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The earliest Anglo-Saxon kingdoms 281

0

0

50

50

100 miles

100 150 km

Norton

ELMET

York

MERCIA

WREOCEN-

SÆTE

Wasperton

WEST SAXONS

Barton

Court Farm

Berinsfield

CHILTERN-

SÆTE

HICCA

Queenford

Farm

Lundenwick

Cowdery's

Down

JUTES

WIGHT

SOUTH SAXONS

EAST

SAXONS

KENT

Canterbury

Mucking

EAST

ANGLES

Snape

Spong

Hill

Yeavering

B

E

R

N

I

C

I

A

N

O

R

T

H

U

M

B

R

I

A

D

E

I

R

A

L

I

N

D

S

E

Y

M

A

G

O

N

S

Æ

T

E

H

W

I

C

C

E

M

I

D

D

L

E

AN

G

L

E

S

Map 8 The main Anglo-Saxon provinces at the time of the composition of the

Tr ibal Hidage, and principal sites mentioned in chapters 10 and 17 (after Yorke

(1990), maps 1 and 2)

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

282 helena hamerow

and power through competition, and ample evidence exists to suggest that

such competition was rife in the sixth century. This has given rise to the

hypothesis that the major kingdoms of the mid Saxon period (c.650–c.850)

were the outcome of intense competition between many much smaller polities

in the sixth century, the more successful groups defeating and absorbing the less

successful, culminating in the seventh century in a small number of dynasties

with supra-regional authority.

82

This model fits well in many respects with both the written and the archaeo-

logical evidence. Of the written sources which survive, of primary importance

is the Tribal Hidage,adocument of probable late seventh-century date and

Mercian or Northumbrian origin, widely assumed to be a tribute list, which

lists thirty-four peoples including (along with the major kingdoms) a number

of small provinciae or regiones, such as the Hicca, for example, with a mere 300

hides.

83

It is tempting to view these small groups as ‘fossils’ of the sixth century,

which for some reason escaped being entirely absorbed by the larger kingdoms

and which managed to maintain some form of separate identity.

84

While this

thesis cannot be proven, it does seem probable that during the sixth century

many such small, unrecorded groups must have existed, at least two of which –

the Elmedsaetna (from Elmet) and the Wihtgara (from the Isle of Wight) both

with 600 hides – had their own rulers, referred to by Bede as reges.

85

South-west

England and Wales also contained a number of sixth-century rulers, the petty

‘kings’ against whom the British cleric Gildas directed his ‘complaint’ in De

Excidio Britanniae, and who, like their Anglo-Saxon counterparts to the east,

seized power in the period following the collapse of Roman rule.

86

Place-names supplement the picture. Those ending in -ingas (referring to

‘the people/followers of x’) are now recognised as having emerged during the

late sixth and early seventh centuries, rather than during the primary period

of settlement in the fifth to early sixth centuries, as once thought.

87

It has

been suggested that the basis of these -ingas groups was not consensual and

founded on a belief in shared descent, but was instead a ‘possessive, imposed

description’.

88

Given that -ingas groups were defined in terms of hides in the

Tribal Hidage (the Faerpingas for example), it does seem likely that by then

they possessed some kind of administrative status, although there is no reason

82

SeeBassett (1989c).

83

SeeDavies and Vierck (1974) and Dumville (1989). See Keynes (1995) for a more sceptical view of

the Tribal Hidage.

84

See Scull (1993), pp. 68–9.

85

See Yorke (1990), p. 11;Bede HE iv.16, 19 and 23.

86

Gildas, De excidio Brit., ed. Winterbottom (text and trans.).

87

Thus, for example, Hastings derives from Haestingas, the people/followers of Haesta. See Dodgson

(1966).

88

SeeHines (1995), p. 82.