Энциклопедия моды. Часть 1. Encyclopedia of Clothing and Fashion (Vol 1)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

from all classes, as well as by little girls with their short

skirts. As The Delineator noted in February 1886 (p. 99),

some women did not wear a bustle pad, “except when

such an adjunct if necessitated by a ceremonious toilette,”

relying instead on a flounced petticoat to support the

drapery of simpler dresses.

After about 1887 the bustle reduced in size and skirts

began to slim. The skirts of the early 1890s featured some

back fullness, but emphasis had shifted to flared skirt hems

and enormous leg-of-mutton sleeves, and bustle supports

were not as fashionable. With skirts fitting snugly to the

hips and derriere in the late 1890s, however, some women

relied on skirt supports to achieve a gracefully rounded

hipline that set off a small waist. While not as extreme as

examples from the mid-1880s, the woven wire or quilted

hip pads worn beyond the turn of century show the tenac-

ity of the full-hipped female ideal.

Despite some historians’ view that bustle fashions were

surely the most hideous ever conceived, this very femi-

nine silhouette has continued to fascinate. In the late 1930s,

Elsa Schiaparelli made playful homage to the bustle in

some of her sleek evening dresses, while late-twentieth-

century bustle interpretations by avant-garde designers,

such as Yohji Yamamoto and Vivienne Westwood, have

utilized the form with historically informed irony.

See also Mantua; Skirt Supports.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Blum, Stella. Victorian Fashions and Costumes from Harper’s Bazar

1867–1898. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1974.

Cunnington, C. Willett. English Women’s Clothing in the Nine-

teenth Century. London: Faber and Faber, 1937. Reprint,

New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1990.

Gernsheim, Alison. Fashion and Reality: 1840–1914. London:

Faber and Faber, 1963. Reprint as Victorian and Edwardian

Fashion: A Photographic Survey. New York: Dover Publica-

tions, Inc., 1981.

Hill, Thomas E. Never Give a Lady a Restive Horse. From Man-

ual of Social and Business Forms: Selections. 1873. Also from

Album of Biography and Art. 1881. Reprint, Berkeley, Calif.:

Diablo Press, 1967.

BUSTLE

205

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF CLOTHING AND FASHION

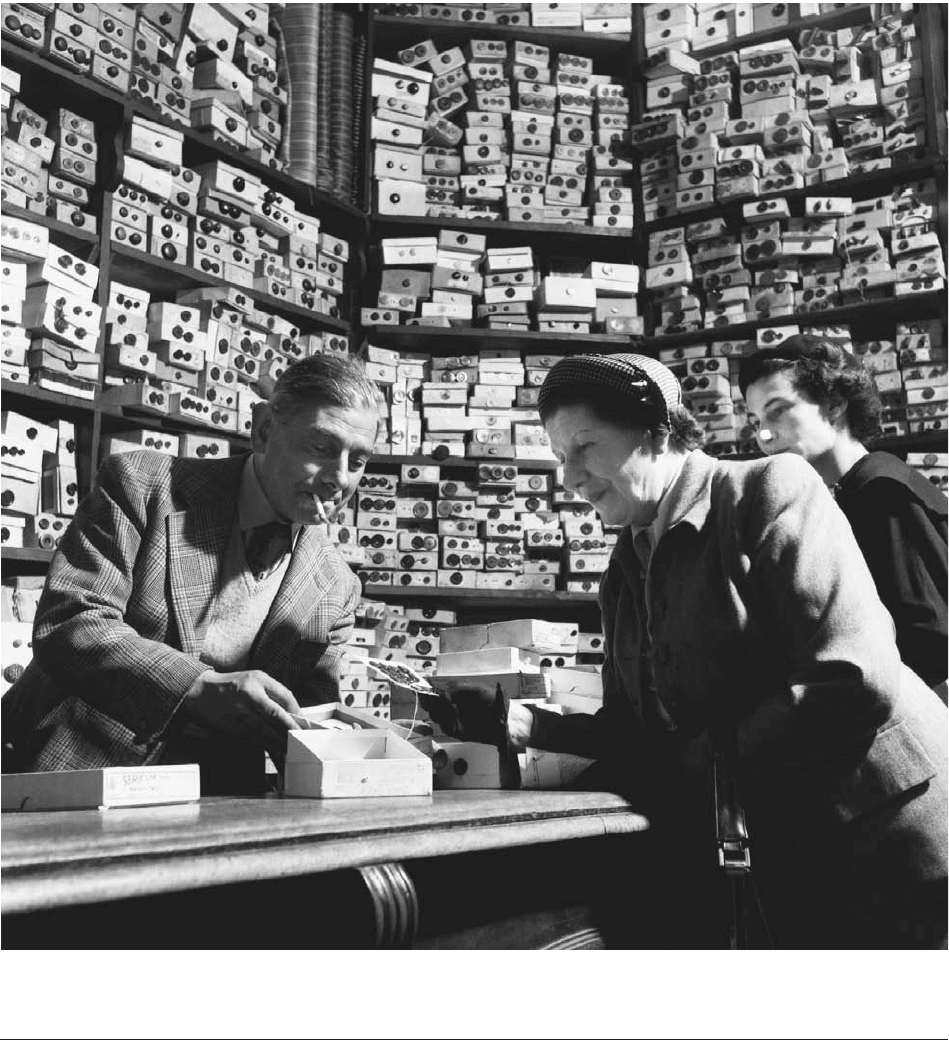

Women wearing bustles. Bustles have been an element of Western fashion intermittently since the seventeenth century. Women’s

dresses were form-fitting on top and created with a tuck and flounce in the back, below the waist, to avoid appearing masculine.

© B

ETTMAN

/C

ORBIS

. R

EPRODUCED BY PERMISSION

.

69134-ECF-B_107-210.qxd 8/16/2004 1:50 PM Page 205

Hughes, Mary Vivian. A London Child of the Seventies. London:

Oxford University Press, 1934.

Rudofsky, Bernard. The Unfashionable Human Body. New York:

Doubleday and Company, 1971.

Severa, Joan. Dressed for the Photographer: Ordinary Americans

and Fashion, 1840–1900. Kent, Ohio: Kent State Univer-

sity Press, 1995.

Waugh, Norah. Corsets and Crinolines. New York: Theatre Arts

Books, 1954.

H. Kristina Haugland

BUTTONS Button-like objects of stone, glass, bone,

ceramic, and gold have been found at archaeological sites

dating as early as 2000

B

.

C

.

E

., but evidence suggests that

these objects were used as decoration on cloth or strung

like beads. Nevertheless, they have the familiar holes

through which to pass a thread, which gives them the ap-

pearance of the button currently known as a fastener.

Buttons can be divided into two types according to

the way they are attached to a garment. Shank buttons

have a pierced knob or shaft on the back through which

passes the sewing thread. The majority of buttons are this

type. The shank can be a separate piece that is attached

to the button or part of the button material itself, as in

a molded button. Pierced buttons have a hole from front

to back of the button so that the thread used to attach

the button is visible on the face.

Almost every material that has been used in the fine

and decorative arts has been used historically in the pro-

duction of buttons. Buttons exist in a variety of materi-

als: metals (precious or otherwise), gemstones, ivory,

horn, wood, bone, mother-of-pearl, glass, porcelain, pa-

per, and silk. In the late nineteenth and twentieth cen-

turies, celluloid and other artificial materials have been

used to imitate natural materials.

Early History

The precursor to the button fastener was the fibula, a

brooch or pin used to hold two pieces of clothing on the

shoulder or chest. The button began to replace the fibula

at least by the early Middle Ages, if not sooner.

Buttons functioned as primary fastenings for men’s

dress earlier than for women’s. This may be due to the

fact that the women’s, from the late Middle Ages into the

twentieth century, was required to be tight and smoothly

fitted. Lacings and hooks are better suited to providing

the strong hold and smooth appearance necessary for

tight-fitting garments.

One of the earliest extant pieces of clothing to show

the use of buttons as fastenings is the pourpoint of

Charles of Blois (c. 1319–1364). This new outer garment

was fitted in the body and sleeves, with buttons used to

close the front and the sleeves from the elbow. At this

point, however, men’s lower garments (hose, and, later,

breeches) were still fastened to their upper garments, or

to an interior belt, by points (laces of ribbon or cord dec-

orated with metal tips). These points with metal tips were

often attached as purely decorative pieces to both male

and female apparel.

There are records of buttons in documents relating

to nobility during the late Middle Ages and the Renais-

sance. For example, Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy

(1396–1497) ordered Venetian glass buttons decorated

with pearls, and Francis I of France (1494–1547) is said

to have ordered a set of black enamel buttons mounted

on gold from a Parisian goldsmith. These were obviously

special buttons of the same quality as contemporary jew-

elry. Buttons of any material were generally round in

shape and made of decorated metal or covered with

needlework in silk or metal threads on a wooden core.

The ball-shaped toggle button is probably the type of

button that replaced the fibula as a fastening for cloaks,

capes, and other outer garments. A sixteenth-century ex-

ample exists in Nuremberg hallmarked silver, attached to

a thin bar by a flexible chain link.

The Eighteenth Century

The eighteenth century is considered the Golden Age of

buttons by collectors, as the variety of styles, as well as

the physical size of buttons increase dramatically. Men’s

coats required buttons at the front opening, sleeves,

pockets, and back vents. Waistcoats and breeches were

also fastened with buttons. The size of the button grows

and the shape generally flattens during the course of the

century, ending in the flat disk as large as 1.38 inch (3.5

cm) in diameter. The value of decorations on a man’s en-

semble during this period, composed of metal thread em-

broidery and jeweled buttons, could account for as much

as 80 percent of the cost of the suit of clothes. Thus, lux-

urious buttons became an increasingly essential part of

the expression of status in upper-class men’s dress. In

Denis Diderot’s Encyclopédie (c. 1746) the creativity of

button-makers is exalted, though for moralists costly but-

tons became one sign of excess in fashion.

The newly fashionable paste jewels (imitation gem-

stones) appeared in the 1730s and were used to create

some of the most highly prized buttons of the nineteenth

century. Georges Frédéric Strass, a Parisian jeweler, per-

fected techniques of making these glass jewels.

As the button evolved from a ball to a flat disk, an-

other notable change in decorative technique was the use

of the button as a palette for painting. Representational

images became immensely popular in the second half of

the eighteenth century and are related to the miniature

portraits that were worn as pendants or pins during the

period. Portraits and subjects like rococo genre scenes,

historical events, tourist views, and architectural monu-

ments were produced. An extraordinary set of French

BUTTONS

206

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF CLOTHING AND FASHION

69134-ECF-B_107-210.qxd 8/16/2004 1:50 PM Page 206

portrait miniature buttons was made about 1790 and in-

cluded portraits of personalities from the French Revo-

lutionary period; each portrait was set in silver with

paste-diamond border and the name of the sitter en-

graved on the back. Artists of note participated in the

production of portrait buttons; Jean-Baptiste Isabey

(1767–1855), a miniature painter and pupil of Jacques-

Louis David, records that he painted decorative buttons

at the beginning of his career.

By the second half of the eighteenth century, button

making in Europe fell into two categories: French button

production remained a craft tradition allied with other

high-quality decorative arts, while the English button in-

dustry developed mass-production techniques. Probably

the most influential of the new English technologies was

the development of cut-steel buttons and accessories by

the steel manufacturer Matthew Bolton (1728–1809) of

Birmingham in the 1760s. Bolton’s cut-steel or faceted

BUTTONS

207

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF CLOTHING AND FASHION

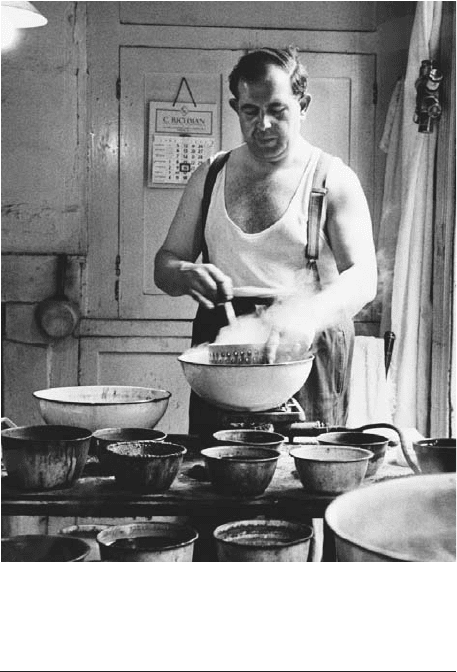

Women shop for buttons in London, 1953. Buttons have been a mainstay of fashion since 2000

B

.

C

.

E

. and continue to hold their

place as an object of function and style. Buttons are created in a variety of materials, including metals, plastics, gem stones, ivory,

horn, wood, bone, mother-of-pearl, glass, porcelain, paper, and silk. © H

ULTON

-D

EUTSCH

C

OLLECTION

/C

ORBIS

. R

EPRODUCED BY PERMISSION

.

69134-ECF-B_107-210.qxd 8/16/2004 1:50 PM Page 207

steel buttons were one of the most prevalent styles of the

last three decades of the eighteenth century. The polished

and faceted surface was created to imitate that of faceted

gems or glass and the effect was quite successful.

The ceramic manufacturer Josiah Wedgwood began

producing buttons made of his popular jasperware in

1773 as part of a collaboration with Matthew Bolton, who

created cut-steel settings for the ceramic buttons. Jasper-

ware ceramics, with their neoclassical motifs derived from

cameos, had become the trademark product of the Wedg-

wood factory and the buttons were available in five col-

ors and a variety of shapes. Another innovation in the

ceramic industry, that of transfer printing, created a new

type of ceramic button decorated with designs derived

from copperplate engravings. At the end of the eigh-

teenth century, buttons made from mother-of-pearl be-

gan to rival in popularity those of steel.

The eighteenth-century Enlightenment sensibility

manifested itself in several unique types of buttons. Faith-

fully depicted insects and animals became the subject of

button sets, as did buttons created from semiprecious ma-

terials such as agate, in which the natural patterns of the

stones were the only decoration. The highlight of this

natural history trend is probably the so-called Habitat

buttons, which contain actual specimens of insects, plants,

or pieces of minerals encased under glass domes.

Nineteenth and Twentieth Century

The standardization of military uniforms in eighteenth-

century Europe led to the production of specialized but-

tons that continues to be a major portion of the button

industry today. The number of buttons required for a sol-

dier’s coat could be as many as twenty to thirty. Each

country, region, and specialization within the armed ser-

vices required their own individual designs. Uniform but-

tons carried over into civilian life, as modern businesses,

such as airlines, and local law enforcement agencies re-

quired special buttons for their uniforms.

Beginning in the early nineteenth century men’s

dress became much plainer and less ostentatious. Por-

traits by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867)

show men’s fashion in the first half of the nineteenth cen-

tury with plain gold metal or fabric buttons of the same

color as the garment on which they are sewn. Women’s

bodices and outerwear became the outlet for the display

of decorative buttons by the mid-nineteenth century.

Women’s buttons followed trends in jewelry: colored

enamel, porcelain, pearl, silver, and jewels were used. Jet

and black glass, introduced during Queen Victoria’s

mourning for Prince Albert, remained popular to the end

of the century.

The nineteenth-century button industry continued

along the two lines that had been established in the eigh-

teenth century; industrial progress continued concur-

rently with handcraft techniques, which generally followed

the historical revival styles of nineteenth-century deco-

rative arts.

In 1812, Aaron Benedict established a metal button-

making factory in Waterbury, Connecticut, to supply

metal buttons for the military. Until that time many metal

buttons were still coming from England, but the War of

1812 brought trade between the United States and

Britain to a halt. As of 2003, Benedict’s company, which

became known as Waterbury Buttons, had been in busi-

ness for 191 years. It is the oldest and largest producer

of stamped metal buttons in the United States. Statistics

from 1996 show that they produced 100 million but-

tons—about one-half for fashion trade and the remain-

der for military and commercial clients. Metal remains

the main type of mass-produced button because the ma-

terial lends itself to mass-production techniques.

The French firm Albert Parent et Cie, founded in

1825, exemplifies the brilliance of French manufacturers

who combined mass-production techniques with the

hand-finished details to produce luxury buttons in the

manner of the eighteenth century. The company left an

archive of sample books showing over 80,000 examples

of buttons in every available technique of the time.

While more buttons were mass-produced in the

nineteenth century that did not mean that fewer materi-

BUTTONS

208

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF CLOTHING AND FASHION

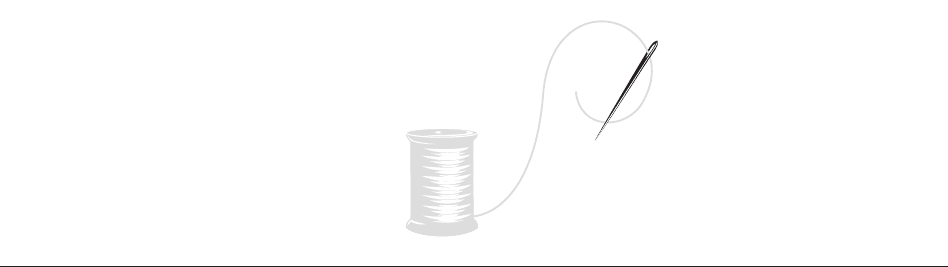

Button dyer at work. Buttons exist in a variety of colors and

motifs and are a critical element in modern dress, as suit jack-

ets and shirts are worn by white collar workers.

© H

ULTON

-

D

EUTSCH

C

OLLECTION

/C

ORBIS

. R

EPRODUCED BY PERMISSION

.

69134-ECF-B_107-210.qxd 8/16/2004 1:50 PM Page 208

als were employed in the creation of buttons. Natural ma-

terials like horn and shells, which had been used for cen-

turies, were rediscovered as mass-produced items. New

materials such as celluloid, the first plastic, were used as

early as the 1870s to imitate other materials.

Representational picture buttons, first introduced in

the late eighteenth century, reached their peak between

1870 and 1914. The nineteenth-century scenes were gen-

erally mass-produced stamped metal designs depicting

any motif imaginable, but contemporary marvels like the

Eiffel Tower were especially popular.

The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries

saw more and more men and women wearing suits with

linen or cotton shirts underneath, the new uniform for

the emerging white-collar working class. Both suit jack-

ets and shirts required buttons as fastenings and they cre-

ated the need for large numbers of inexpensive buttons.

Thus, the four-holed pierced button was introduced to

both men’s and women’s fashions. However, fine jewelry

quality buttons were still produced by some of the best-

known retailers of the day such as Cartier, Liberty’s of

London, and Georg Jensen.

Buttons received competition in the form of the new

zipper that was patented in 1903 but did not come into

general use until the 1930s. The zipper was considered

a novelty at first and played a prominent role as decora-

tion in the designs of top designers.

Bakelite was invented in 1907 and by the 1930s had

replaced almost all other synthetics for accessories.

Durable and versatile, Bakelite was the medium for

some of the most extravagant buttons of the twentieth

century, but other plastics eventually replaced it. Three-

dimensional accessories, such as fruit shapes, were cre-

ated in the 1930s and 1940s when small accessories like

buttons were especially popular. The designer Elsa Schi-

aparelli (1890–1973), who was allied with surrealist

artists in the 1930s, is notable for her use of extraordi-

nary custom-made buttons.

Plastics replaced most inexpensive glass and pearl

buttons by the 1960s. That coupled with the fact that

natural materials such as ivory and tortoiseshell are now

banned in the United States and other countries has led

to the dominance of plastic buttons made to imitate these

materials. Mother-of-pearl is still used but in much smaller

quantities than in the past. American-made pearl buttons

can cost from twenty-five cents to three dollars apiece, as

some of the work must still be done by hand and the best

shells are imported from the Pacific Ocean coastlines.

The use of stretch fabrics and increasingly informal

dressing have led to a decrease in the demand for button

fasteners. They have become a symbol of nostalgia and

anachronistic tradition, as evidenced by retro button-fly

jeans introduced by denim manufacturers in the 1990s

and the continued use of rows of tiny buttons on the back

of bridal gowns.

Buttons have become extremely collectible. The Na-

tional Button Society exists for collectors and publishes

a quarterly bulletin and holds an annual meeting and

show. There are similar societies in Britain and Australia

and elsewhere in the world. Military buttons represent a

specialty among collectors, as the challenge of identify-

ing the insignias of segments of the armed services adds

to the interest of these items.

See also Fasteners; Zipper.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Boucher, Francois. 20,000. Years of Fashion: The History of Cos-

tume and Personal Adornment. New York: Harry N. Abrams,

1987.

DeMasters, Karen. “New Jersey & Co. Out of the Dust Emerge

Lustrous Buttons.” New York Times, 4 April 1999.

Epstein, Diana, and Millicent Safro. Buttons. New York: Harry

N. Abrams, 1991.

Houart, Victor. Buttons: A Collector’s Guide. London: Souvenir

Press Ltd., 1977.

Pearsall, Susan. “In Waterbury, Buttons Are Serious Business.”

New York Times, 3 August 1997.

Roche, Daniel. The Culture of Clothing: Dress and Fashion in the

Ancient Régime. New York: Cambridge University Press,

1996.

Melinda Watt

BUTTONS

209

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF CLOTHING AND FASHION

69134-ECF-B_107-210.qxd 8/16/2004 1:50 PM Page 209

CACHE-SEXE The term “cache-sexe” refers to a cov-

ering for the female genitals. The term is derived from

the French cacher, which means to hide, and sexe, which

means genitals. Other terms used synonymously are mod-

esty apron, marriage apron, modesty skirt, loincloth,

string skirt, and girdle. The choice of term appears to be

related to the country of origin or discipline of the ob-

server. In this case, “cache-sexe” appears to be the term

used in those areas of the African continent that were col-

onized by the French, such as the region from western

Mali to southern Cameroon. Cache-sexe are used

throughout much of West Africa and parts of East Asia,

where the term modesty apron is more commonly used.

In short, a wide variety of terms are employed to describe

an article of dress that offers insight into the life ways of

women in some small-scale societies.

Cache-sexe are constructed of a variety of materials

including woven fabric, leather, beads, leaves, and met-

als. For example, cache-sexe created by the Kirdi (Fulani)

women in northern Cameroon are skirts beaded with a

fantastic range of colors. Cowry shells and brass beads

ornament and give weight to the fringe. Cowry shells

originate in the Maldive Islands, off the western coast of

India, indicating Kirdi linkages to long distance trade.

Cache-sexe are worn low on the hip and tied with a cord.

Regardless of materials, the skirts measure approximately

twelve to eighteen inches in length and twenty to twenty-

two inches in width, excluding the cord.

The cache-sexe can be traced to the Paleolithic pe-

riod, where stone carvings of fecund women, such as the

Venus of Lespugue, depict panels of string fore and aft.

String skirts dating from the fourteenth century

B

.

C

.

E

.

have been uncovered in burial sites in Denmark. These

skirts are wool, also ride low on the hip, fall to just above

the knees, and wrap around the body twice. The cords

of the skirt are thickly plied and knotted at the bottom,

so that the skirt “must have had quite a swing to it” (Bar-

ber, p. 57). One of the oldest African examples of cache-

sexe is described as a girdle from twelfth-century Mali.

It can be described as a three-layer belt with very long

fringes. The inner bark of the baobab tree is believed to

be the source of the strands of fiber, which are plaited

and twined into a solid chevron pattern. Its manufacture

is closely related to the techniques used to produce snares,

nets, and baskets. This specific article of dress is signifi-

cant because it was once believed that dress was intro-

duced to sub-Saharan Africa by the spread of Islam.

However, this object predates the expansion of Islam and

is made of local, not imported, materials.

Cache-sexe appear to be exclusive to females. When

and how a woman wears a cache-sexe varies from society

to society. In some, a girl begins to wear the skirt after

menarche; in others menarche is recognized by a change

from a small leather panel skirt to a fringed skirt that

wraps all the way around the body. In visual sources of

information, cache-sex are part of an ensemble that in-

cludes necklaces or supplements to the nose. In parts of

New Guinea and Irian Jaya, women use knitted net bags

that hang from a strap across the forehead. In twentieth-

century images women can be seen wearing brassieres,

T-shirts, and blouses.

Female informants report that protection from the

environment is the main reason they wear cache-sexe.

However, because of the open styling of the of the skirt,

either as panels hanging in front and back or as fringes,

it may be less effective as physical protection than as spir-

itual protection. For example, in Papua New Guinea, the

Doni believe that ghosts can attack vulnerable areas like

the anal opening. Articles of dress with ritual power, such

as the cache-sexe, are used to protect, if not actually con-

ceal, the lower body against evil.

Like the penis sheath, one function of the cache-sexe

was thought to be modesty. A more likely interpretation

of this act of dressing has more to do with fulfilling a

group aesthetic about standards of public appearance.

Not wearing a cache-sexe is a visible statement of a

woman’s inability or unwillingness to participate in so-

cial interaction, as when ill or in mourning.

Indeed, the main function of the cache sexe, like the

penis sheath, appears to be one of drawing attention to

the female secondary sex characteristics by intermittently

concealing them. In her contemplation of Paleolithic

string skirts, Barber states:

To solve the mystery of why they were [worn], I think

we must follow our eyes. Not only do the skirts hide

nothing of importance, but also if anything, they at-

tract the eye precisely to the specifically female sexual

211

C

69134-ECF-C_211-332.qxd 8/16/2004 2:27 PM Page 211

areas by framing them, presenting them, or playing

peekaboo with them. . . . Our best guess, then is that

string skirts indicated something about the childbear-

ing ability or readiness of a woman, … that she was in

some sense “available” as a bride. (p. 59)

Thus, the cache sexe, by any other name, is exclu-

sively a female symbol. Like the penis sheath, it is more

than a covering or a display. It is a unique form of ma-

terial culture that draws one in to an understanding of

the physical, social, and aesthetic life of women in some

small-scale cultures.

See also Penis Sheath.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barber, Elizabeth Wayland. Women’s Work: The First 20,000

Years. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1994.

Heider, Karl G. “Attributes and Categories in the Study of Ma-

terial Culture: New Guinea Dani Attire.” Man 4, no. 3

(1969): 379–391.

Hersey, Irwin. “The Beaded Cache-Sexe of Northern

Cameroon.” African Arts 8, no. 2 (winter 1975): 64.

O’Neill, Thomas. “Irian Jaya: Indonesia’s Wild Side.” National

Geographic 189, no. 2 (February 1996): 2–34.

Steinmetz, George. “Irian Jaya’s People of the Trees.” National

Geographic 189, no. 2 (February 1996): 35–43.

Symonds, Patricia V. Calling the Soul: Gender and the Cycle of Life

in a Hmong Village. Seattle: University of Washington

Press, 2003.

Sandra Lee Evenson

CAFTAN The term “caftan” (from Ottoman Turkish

qaftan) is used to refer to a full-length, loosely-fitted gar-

ment with long or short sleeves worn by both men and

women, primarily in the Levant and North Africa. The

garment may be worn with a sash or belt. Some caftans

open to the front or side and are tied or fastened with

looped buttons running from neck to waist. Depending

on use, caftans vary from hip to floor length. The caftan

is similar to the more voluminous djellaba gown of the

Middle East. Contemporary use of the label “caftan”

broadens the term to encompass a number of similarly

styled ancient and modern garment types.

The origin of the caftan is usually tied to Asia Minor

and Mesopotamia. Caftan-like robes are depicted in the

palace reliefs of ancient Persia dating to 600

B

.

C

.

E

. By the

thirteenth century

C

.

E

., the style had spread into Eastern

Europe and Russia, where caftan styles provided the

model for a number of different basic garments well into

the nineteenth century (Yarwood 1986, p. 321, 62). The

caftan tradition was particularly elaborate in the imperial

wardrobes of the sixteenth-century Ottoman Empire in

Anatolian Turkey. Caftans of varying lengths constructed

from rich Ottoman satins and velvets of silk and metallic

threads were worn by courtiers to indicate status, pre-

served in court treasuries, used as tribute, and given as

“robes of honor” to visiting ambassadors, heads of state,

important government officials, and master artisans work-

ing for the court (Atil 1987, p. 177, pp. 179–180.) Men’s

caftans often had gores added, causing the caftan to flare

at the bottom, while women’s garments were more closely

fitted. Women were more likely to add sashes or belts. A

sultan and his courtiers might layer two or three caftans

with varying length sleeves for ceremonial functions. An

inner short-sleeved caftan (entari), was usually secured

with an embroidered sash or jeweled belt, while the outer

caftan could have slits at the shoulder through which the

wearer’s arms were thrust to display the sleeves (some-

times with detachable expansions) of the inner caftan to

show off the contrasting fabrics of the garments (1987,

pp. 182–198; p. 348). Loose pants gathered at the ankle

or skirts were worn under the entari.

Caftan-style robes are worn in many parts of the

world where Islam has spread, particularly in North and

West Africa. In parts of West Africa, the practice of lay-

ering robes to express the aesthetic principle of “bigness”

in leadership dress (Perani and Wolff 1999, pp. 90–95)

and the giving of “robes of honor” is shared with the Ot-

toman tradition (Kriger 1988).

In Western culture, caftans became part of the in-

ternational fashion scene in the mid-twentieth century.

In the 1950s, French designer Christian Dior adapted the

caftan style to design women’s floor-length evening coats

(O’Hara 1986, p. 60). In the 1960s, the caftan as a uni-

sex garment gained visibility as hippie trendsetters

adopted ethnic dress. Largely through the influence of

fashion maven Diana Vreeland, the editor of Vogue mag-

azine, the caftan entered into the haute couture fashion

scene. After a visit to Morocco in the early 1960s, Vree-

land published a series of articles in Vogue championing

the caftan as fashionable for “The Beautiful People”

(Harrity 2003). Yves Saint Laurent and Halston were de-

signers who included caftan-styled clothing in their lines

(O’Hara 1986, p. 60). Since that time, caftans continue

to have a market for evening and at-home wear for

women and a more limited market with homosexual

males (Harrity 2003). The caftan is now marketed glob-

ally as “fashion.” Contemporary designers draw their in-

spiration from a number of different historic traditions.

For example, Hubert Givenchy draws upon the Middle

Eastern tradition. African designers present the “dashiki

caftan” based on West African prototypes. The J. Peter-

man Company markets a “Shang Dynasty Caftan” for

women, copied from a Chinese silk ceremonial robe

dated to 2640

B

.

C

.

E

. In this globalization of the caftan,

top Italian designers began marketing costly “designer

caftans” in materials as diverse as silk and sheared mink

to elite women of the Arab Middle East nations (Time

International, Dec. 9, 2002).

See also Djellaba; Iran: History of Dress; Middle East: His-

tory of Islamic Dress.

CAFTAN

212

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF CLOTHING AND FASHION

69134-ECF-C_211-332.qxd 8/16/2004 2:27 PM Page 212

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Atil, Esin. The Age of Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent. Wash-

ington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art; New York: Harry

N. Abrams, Inc., 1987. Includes an excellent discussion of

sixteenth-century imperial Ottoman caftans in the collec-

tion of the Topkapi Palace in Turkey.

Kriger, Coleen. “Robes of the Sokoto Caliphate.” African Arts

21, no. 3 (1988): 52–57, 78–79.

O’Hara, Georgina. The Encyclopaedia of Fashion. New York:

Harry N. Abrams, 1986.

Perani, Judith, and Norma H. Wolff. Cloth, Dress, and Art Pa-

tronage in Africa. Oxford and New York: Berg Press, 1999.

Stillman, Yedida Kalfon. Arab Dress: A Short History from the

Dawn of Islam to Modern Times. Boston: Brill, 2000.

Yarwood, Doreen. The Encyclopedia of World Costume. New York:

Bonanza Books, 1986.

Internet Resources

Calderwood, Mark. “Ottoman Costume: An Overview of Six-

teenth Century Turkish Dress.” 2000. Available from

<http://www.geocities.com/kaganate>.

Harrity, Christopher. “Will You Know When It’s Caftan

Time?” July 25, 2003. Available from <http://www

.advocate.com>

Norma H. Wolff

CALICO In the United States, the word “calico” refers

to cotton cloth printed with tiny, tightly spaced, colorful

motifs on a colored background. Because many people

perceive it as pleasantly old-fashioned, calico has long

found favor with quilt makers and it occasionally appears

in children’s wear. In the early twentieth century, instead

of jeans or knits, women typically wore calico dresses and

aprons to do housework.

Calico of the late 1500s was another matter. The

Portuguese, intent upon being the first Europeans to

trade for spices directly in the Malay archipelago, had ar-

rived in Calicut, India. There they encountered colored

and uncolored cotton cloths of all descriptions, which

they designated generally as “calicoes.” Perhaps by de-

fault, “calico” very gradually acquired a secondary mean-

ing in reference to basic, unelaborated cottons lacking

the distinctive characteristics of other ones like “dunga-

ree” or “gingham.”

Calico in Early Commerce

Centuries before European traders disembarked in India,

a wide range of Indian calicos, including painted or

printed ones called chintes, were carried by Arab traders

to Turkey, the Levant, and North Africa as well as South-

east Asia. Through their Mediterranean trade connec-

tions, wealthy Europeans had enjoyed imported spices

and Indian quilted silks. They knew—or desired—little

of the cottons, although Armenian entrepreneurs man-

aged a calico trade along with spices and silks.

Early in their enterprise, Portuguese, Dutch, and

English spice traders learned to appreciate cotton because

the spice islanders would not sell their merchandise rea-

sonably for anything other than their preferred Indian

cloths—or opium. Thus enmeshed in calico trading, the

traders sent quantities of the cheapest—probably left-

overs—and some of the most luxurious kinds back home

on private speculation or as curiosities. These generated

a voracious European market; by the 1660s calico im-

ports had become big business. Fine and heavy linens

both could be replaced by the more affordable cottons;

the chintes or prints were like nothing else.

English traders further expanded their operations

by selling calicos to other companies that profitably

exported them to Europe and the old-established

Mediterranean and Levantine markets. They discovered

lucrative markets in West Africa where, in the 1630s,

they began selling special checked and striped calico as

barter for slaves. The unsold remainders were sold in

the West Indies for slave clothing and returned in the

form of tobacco and sugar.

Indian Chintes

The processes of indigo resist dyeing and of applying mor-

dants to selected areas of a cloth prior to dyeing in chay

(madder) are thought to have originated in ancient times

in India. The colored designs were not only brilliant, but

fast, or laundry-proof—traits which riveted European

imaginations and dollars. Common qualities looked crude

because they were produced by the shortcut method of

block printing, which also compromised the purity of the

colors; printed calicos were inexpensive or downright

cheap, and not cherished. The best goods, kalamkari,

commanded a much higher price than printed ones, for

they were hand painted—a time-consuming, laborious

method that moved one exasperated entrepreneur to make

remarks about creeping snails. These are the treasures that

came to rest in museum collections.

CALICO

213

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF CLOTHING AND FASHION

G

LOSSARY OF

T

ECHNICAL

T

ERMS

Madder: Natural red dye obtained from the root of a

Eurasian plant,

Rubia tinctoria.

Mordant: A substance used in dyeing that helps to

make the dye color more stable and permanent.

Resist dyeing: Any of a number of dyeing techniques

in which part of the yarn or fabric is covered with

some material that prevents the penetration of the

dyestuff.

69134-ECF-C_211-332.qxd 8/16/2004 2:27 PM Page 213

Europeans and Chintes

European textiles had woven designs, manipulated sur-

faces, or applied decorations, and, apart from humble

stripes and checks, these added significantly to the ex-

pense. They were difficult to maintain. Some handker-

chiefs were printed with ink—not dye—to make handy

city maps or other novelties that were not laundry-proof.

Dutch gentlewomen were pleased to wear India

chintes but English ladies at first disdained them because

the “meaner sort” already had embraced the cheap piece

goods that first came along. By the 1660s, however, the

upper classes in Europe and America were eagerly aug-

menting their wardrobes with washable banyans and

other informal attire made of calicos custom-painted to

CALICO

214

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF CLOTHING AND FASHION

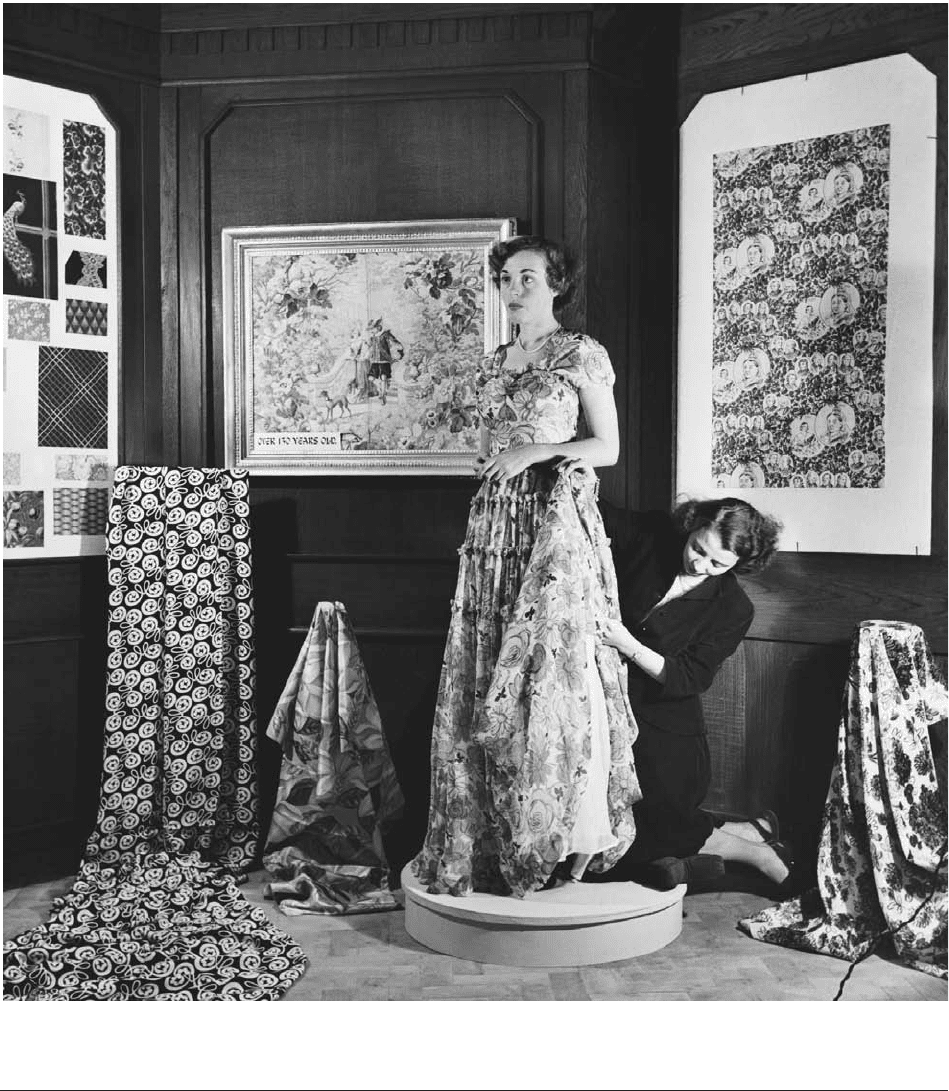

A designer arranges a calico dress on a model. Calicos became so popular in France and England in the 1700s that both coun-

tries prohibited importing, printing, wearing, and using cottons in an effort to protect their own textile industry.

© H

ULTON

-D

EUTSCH

C

OLLECTION

/C

ORBIS

. R

EPRODUCED BY PERMISSION

.

69134-ECF-C_211-332.qxd 8/16/2004 2:27 PM Page 214

their taste. Everyone wanted chintes for the irresistible

combination of eye-appeal, comfort, and launderability.

European Printed Calico

When Europeans decided to try their own hands at print-

ing in the 1600s, they printed on Indian calico. To elim-

inate the problems of dependence upon imported cloth,

over the next century England led in developing ma-

chinery for cotton spinning and weaving. By 1800, Eli

Whitney’s American cotton gin enabled a steady supply

of American raw cotton to busy mills. All the while, print-

ing processes were becoming highly mechanized.

Because European designs were necessarily block

printed—painting was too slow and tedious—the mor-

dants required thickening. The trick was to concoct

thickeners that gave clean imprints with minimal dulling

of the colors. The development of better colors con-

cerned all; mineral dyes and steaming were explored. Dye

chemistry became a new field of research. In all aspects

of calico manufacture, competition was fierce and indus-

trial espionage rampant; production exploded.

European Resistance to Calico

The path to commercial success was not straightforward.

To protect its own textile manufacturers, France enacted

a complex succession of prohibitions against importing,

printing, wearing, and using chintes and cottons, effec-

tively destroying its own opportunities from 1686 to

1759. In 1701, established English manufacturers got

similar satisfaction, notably in the form of prohibitions

against using, wearing, and importing calicos except for

re-export. This was augmented twenty years later by pro-

hibitions against using or wearing painted, printed, or

dyed cottons made at home, with the exception of printed

linens or fustians (linen warp with cotton weft) which

were taxed. From 1774 to 1811, cottons woven with three

blue selvage threads could be printed for export and a tax

drawback obtained. Smuggling and subterfuge ensured

that the market remained supplied; legal attempts to foil

calico consumption were eventually abandoned.

Cotton and prints became accepted as facts of life.

America gradually joined England, France, Holland,

Germany, and Switzerland in the business of printing cot-

tons. England surpassed its own reputation as the world’s

source of fine wools to become the world’s source of plain

and printed cotton cloth, exporting cheap cotton even to

India by the 1840s.

Calicos are often made at least partly of polyester in

the twenty-first century, and it may be safe to say that

anyone who wears clothes has worn calico—a phenome-

non founded on the ambitions of European spice traders

to get to the pepper first. It could be argued that the in-

dustrial revolution happened in order to generate and

supply a global appetite for calico. Machinery, chemistry,

and transportation all tumbled into place seemingly to

accomplish this purpose.

See also Chintz.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brédif, Josette Toiles de Jouy. London: Thames and Hudson,

Inc., 1989.

Irwin, John, and P. R. Schwartz. Studies in Indo-European Tex-

tile History. Ahmedabad, India: Calico Museum of Textiles,

1966.

Irwin, John, and Katharine B. Brett. Origins of Chintz. London:

Her Majesty’s Stationer’s Office, 1970.

Susan W. Greene

CALLOT SISTERS The Paris couture house Callot

Sisters was founded in 1895 by four sisters, Marie Ger-

ber, Marthe Bertrand, Régine Tennyson-Chantrelle, and

Joséphine Crimont, at 24, rue Taitbout. The sisters came

from an artistic family; their mother was a talented lace

maker and embroiderer, and their father, Jean-Baptiste

Callot, was an artist who came from a family of lace mak-

ers and engravers (including the esteemed seventeenth-

century artist Jacques Callot) and taught at the École

nationale supérieure des beaux-arts. Before opening the

couture salon, the sisters owned a shop that sold antique

laces, ribbons, and lingerie. Madame Gerber was gener-

ally acknowledged as the head designer and had worked

as a modéliste (a designer who works under the house name

but is not credited) with the firm Raudnitz et cie. By 1900

Callot Sisters was employing six hundred workers and had

CALLOT SISTERS

215

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF CLOTHING AND FASHION

An engraver puts a design onto a printing roller. Hand-

painted calico was very time-consuming and expensive to pro-

duce, and processes for printing and dyeing calico fabric were

developed during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

© B

ETTMAN

/C

ORBIS

. R

EPRODUCED BY PERMISSION

.

69134-ECF-C_211-332.qxd 8/16/2004 2:27 PM Page 215