Duiker William J., Spielvogel Jackson J. The Essential World History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

called up for military service. Nazi magazines now pro-

claimed, ‘‘We see the woman as the eternal mother of our

people, but also as the working and fighting comrade of

the man.’’

8

But the number of women working in in-

dustry, agriculture, commerce, and domestic service in-

creased only slightly. The total number of employed

women in September 1944 was 14.9 million, compared

with 14.6 million in May 1939. Many women, especially

those of the middle class, resisted regular employment,

particularly in factories.

Wartime Japan was a highly mobilized society. To

guarantee its control over all national resources, the gov-

ernment set up a planning board to control prices, wages,

the utilization of labor, and the allocation of resources.

COMPARATIVE ESSAY

P

ATHS TO MODERNIZATION

To the casual observer, the most important feature

of the first half of the twentieth century was the

rise of a virulent form of competitive nationalism

that began in Europe and ultimately descended

into the cauldron of two destructive world wars. Behind the

scenes, however, the leading countries were also engaging in

another form of competition over the most effective path to

modernization.

The traditional approach, fostered by an independent urban mer-

chant class, had been adopted by Great Britain, France, and the

United States and led to the emergence of democratic societies on

the capitalist model. A second approach, adopted in the late nine-

teenth century by imperial Germany and Meiji Japan, was carried

out by traditional elites in the absence of a strong independent

bourgeois class. They relied on strong government intervention to

promote the growth of national wealth and power and led ultimately

to the formation of fascist and militarist regimes during the depres-

sion years of the early 1930s.

The third approach, selected by Vladimir Lenin after the

Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, was designed to carry out an indus-

trial revolution without going through an intermediate capitalist

stage. Guided by the Communist Party in the almost total absence

of an urban middle class, this approach envisaged the creation of an

advanced industrial society by destroying the concept of private

property. Although Lenin’s plans ultimately called for the ‘‘withering

of the state,’’ the party adopted totalitarian methods to eliminate en-

emies of the revolution and carry out the changes needed to create a

future classless utopia.

How did these various approaches contribute to the series of

crises that afflicted the world during the first half of the twentieth

century? The democratic-capitalist approach proved to be a consid-

erable success in an economic sense, leading to the creation of ad-

vanced economies that could produce manufactured goods at a rate

never seen before. Societies just beginning to undergo their own

industrial revolutions tried to imitate the success of the capitalist

nations by carrying out their own ‘‘revolutions from above’’ in

Germany and Japan. But the Great Depression and competition over

resources and markets soon led to an intense rivalry between the

established capitalist states and their ambitious late arrivals, a rivalry

that ultimately erupted into global conflict.

In the first decade of the twentieth century, imperial Russia

appeared ready to launch its own bid to join the ranks of the indus-

trialized nations. But that effort was derailed by its entry into World

War I, and before that conflict had come to an end, the Bolsheviks

were in power. Isolated from the capitalist marketplace by mutual

consent, the Soviet Union was able to avoid being dragged into the

Great Depression but, despite Stalin’s efforts, was unsuccessful in

staying out of the ‘‘battle of imperialists’’ that followed at the end of

the 1930s. As World War II came to an end, the stage was set for a

battle of the victors---the United States and the Soviet Union---over

political and ideological supremacy.

Q

What were the three major paths to modernization in the

first half of the twentieth century, and why did they lead to

conflict?

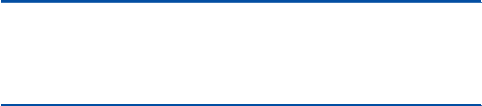

The Soviet Path to Modernization. One aspect of the Soviet effort

to create an advanced industrial society was to collectivize agriculture,

which included a rapid mechanization of food production. Seen here are

peasants watching a new tractor at work.

c

Bettmann/CORBIS

634 CHAPTER 25 THE CRISIS DEEPENS: WORLD WAR II

Traditional habits of obedience and hierarchy, buttressed

by the concept of imperial divinity, were emphasized to

encourage citizens to sacrifice their resources, and some-

times their lives, for the national cause. The system cul-

minated in the final years of the war, when young Japanese

were encouraged to volunteer en masse to serve as pilots

in the suicide missions (known as kamikaze, ‘‘divine

wind’’) against U.S. battleships.

Women’s rights too were to be sacrificed to the

greater national cause. Already by 1937, Japanese women

were being exhorted to fulfill their patriotic duty by

bearing more children and by espousing the slogans of the

Greater Japanese Women’s Association. Japan was ex-

tremely reluctant to mobilize women on behalf of the war

effort, however. General Hideki Tojo, prime minister

from 1941 to 1944, opposed female employment, arguing

that ‘‘the weakening of the family system would be the

weakening of the nation. ... We are able to do our duties

only because we have wives and mothers at home.’’

9

Female employment increased during the war, but only in

areas where women traditionally worked, such as the

textile industry and farming. Instead of using women to

meet labor shortages, the Japanese government brought

in Korean and Chinese laborers.

The Frontline Civilians:

The Bombing of Cities

Bombing was used in World War II against a variety of

targets, including military targets, enemy troops, and

civilian populations. The bombing of civilians made

World War II as devastating for civilians as for frontline

soldiers. A small number of bombing raids in the last year

of World War I had given rise to the argument that public

outcry over the bombing of civilian populations would be

an effective way to coerce governments into making peace.

Consequently, European air forces began to develop long-

range bombers in the 1930s.

The first sustained use of civilian bombing contra-

dicted the theory. Beginning in early September 1940, the

German Luftwaffe subjected London and many other

British cities and towns to nightly air raids, making the

Blitz (as the British called the German air raids) a na-

tional experience. Londoners took the first heavy blows

but kept up their morale, setting the standard for the rest

of the British population (see the comparative illustration

on p. 636).

The British failed to learn from their own experi-

ence, however; Prime Minister Winston Churchill and

his advisers believed that destroying German commu-

nities would break civilian morale and bring victor y.

Major bombing raids began in 1942. On May 31, 1942,

Cologne became the first German city to be subjected to

an attack by a thousand bombers. Bombing raids added

an element o f terror to circumstances already made

difficult by growing shor tages of food, clothing, and

fuel. Germans especially feared incendiar y bombs,

which ignited firestorms that swept destructive paths

through the cities. The ferocious bombing of Dresden

from February 13 t o 15, 1945, set off a firestorm that

mayhavekilledasmanyas35,000inhabitantsand

refugees.

Germany suffered enormously from the Allied

bombi ng raids. Millions of buildin gs were destroyed,

and possibly half a million civilians died from the raids.

Nevertheless, it is highly unlikely that Allied bombing

sapped the morale of the German people. Instead

Germans, whether pro-Nazi or anti-Nazi, foug ht on

stubbornly, often driven simply by a desire to live. Nor

did the bombing destroy Germany’s industrial capacity.

The Allied strategic bombi ng survey revealed tha t the

production of war mat

eriel actually increased between

1942 and 1944.

In Japan, the bombing of civilians reached a hor-

rendous new level with the use of the first atomic bomb.

Attacks on Japanese cities by the new American B-29

Superfortresses, the biggest bombers of the war, had be-

gun on November 24, 1944. By the summer of 1945,

many of Japan’s industries had been destroyed, along with

one-fourth of its dwellings. After the Japanese govern-

ment decreed the mobilization of all people between the

ages of thirteen and sixty into the so-called People’s

Volunteer Corps, President Truman and his advisers de-

cided that Japanese fanaticism might mean a million

American casualties, and Truman decided to drop the

newly developed atomic bomb on Hiroshima and

Nagasaki. The destruction was incredible. Of 76,000

buildings near the hypocenter of the explosion in Hi-

roshima, 70,000 were flattened, and 140,000 of the city’s

400,000 inhabitants had died by the end of 1945. Over the

next five years, another 50,000 perished from the effects

of radiation. The dropping of the atomic bomb on

Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, announced the dawn of the

nuclear age.

Aftermath of the War

Q

Focus Questions: What wer e the costs of World War II?

How did the Allies’ visions of the postwar differ , and

how did these differences contribute to the emergenc e

of the Cold War?

World War II was the most destructive war in history.

Much had been at stake. Nazi Germany followed a

worldview based on racial extermination and the

AFTERMATH OF THE WAR 635

enslavement of millions in order to create an Aryan racial

empire. The Japanese, fueled by extreme nationalist ide-

als, also pursued dreams of empire in Asia that led to

mass murder and untold devastation. Fighting the Axis

Powers in World War II required the mobilization of

millions of ordinary men and women in the Allied

countries who struggled to preserve a different way of life.

As Winston Churchill once put it, ‘‘War is horrible, but

slavery is worse.’’

The Costs of World War II

The costs of World War II were enormous. At least 21

million soldiers died. Civilian deaths were even greater

and are now estimated at around 40 million. Of these,

more than 28 million were Russian and Chinese. The

Soviet Union experienced the greatest losses: 10 million

soldiers and 19 million civilians. In 1945, millions of

people around the world fa ced starvation: in Europe,

100 million people depended on food relief of some

kind.

Millions of people had also been uprooted by the

wa r and became ‘‘displaced persons.’’ Europe alone may

have had 30 million displaced person s, many of whom

found it hard to return home. In Asia, millions of

Japanese were returned from the former Japanese em-

pire to Japan, while thousands of Korean forced laborers

ret urned to Korea.

Everywhere cities lay in ruins. In Europe, the physical

devastation was especially bad in eastern and southeastern

Europe as well as in the cities of western and central

Europe. In Asia, China had experienced extensive devas-

tation from eight years of conflict. So too had the

Philippines, while large sections of the major cities in

Japan had been destroyed in air raids. The total monetary

cost of the war has been estimated at $4 trillion.

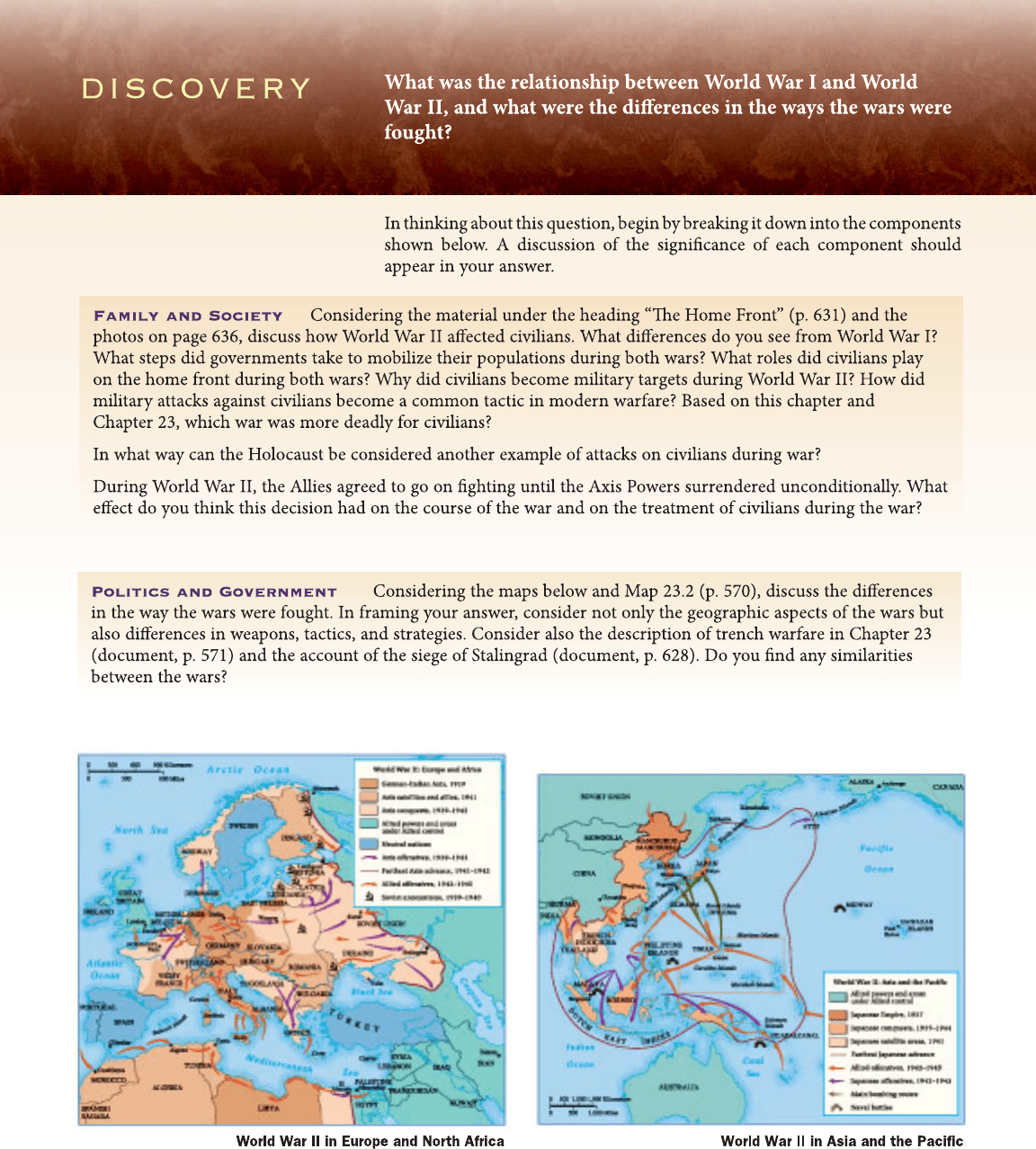

COMPARATIVE ILLUSTRATION

The Bombing of Civilians— East and West. World War II was the most

destructive war in world history, not only for frontline soldiers but for civilians at

home as well. The most devastating bombing of civilians came near the end of

World War II when the United States dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of

Hiroshima and Nagasaki. At the left is a view of Hiroshima after the bombing that shows the

incredible devastation produced by the atomic bomb. The picture at the right shows a street in

Clydebank, near Glasgow in Scotland, the day after the city was bombed by the Germans in

March 1941. Only 7 of the city’s 12,000 houses were left undamaged; 35,000 of the 47,000

inhabitants became homeless overnight.

Q

What was the rationale for bombing civilian populations? Did such bombing achieve

its goal?

c

J.R. Eyeman/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images

c

Keyston/Getty Images

636 CHAPTER 25 THE CRISIS DEEPENS: WORLD WAR II

The economies of most belligerents, with the exception of

the United States, were left on the brink of disaster.

The Allied War Conferences

Stalin, Roosevelt, and Churchill, the leaders of the Big

Three of the Grand Alliance, met at Tehran, the capital

of Iran, in November 1943 to decide the future course

of the war. Stalin and Roosevelt argued successfully for

an American-British invasion of the Continent through

France, which they scheduled for the spring of 1944.

This meant that Soviet and British-American forces

would meet in defeated Germany along a north-south

dividing line and that Soviet forces would liberate

eastern Europe. The All ies also agreed to a partition of

postwar Germany.

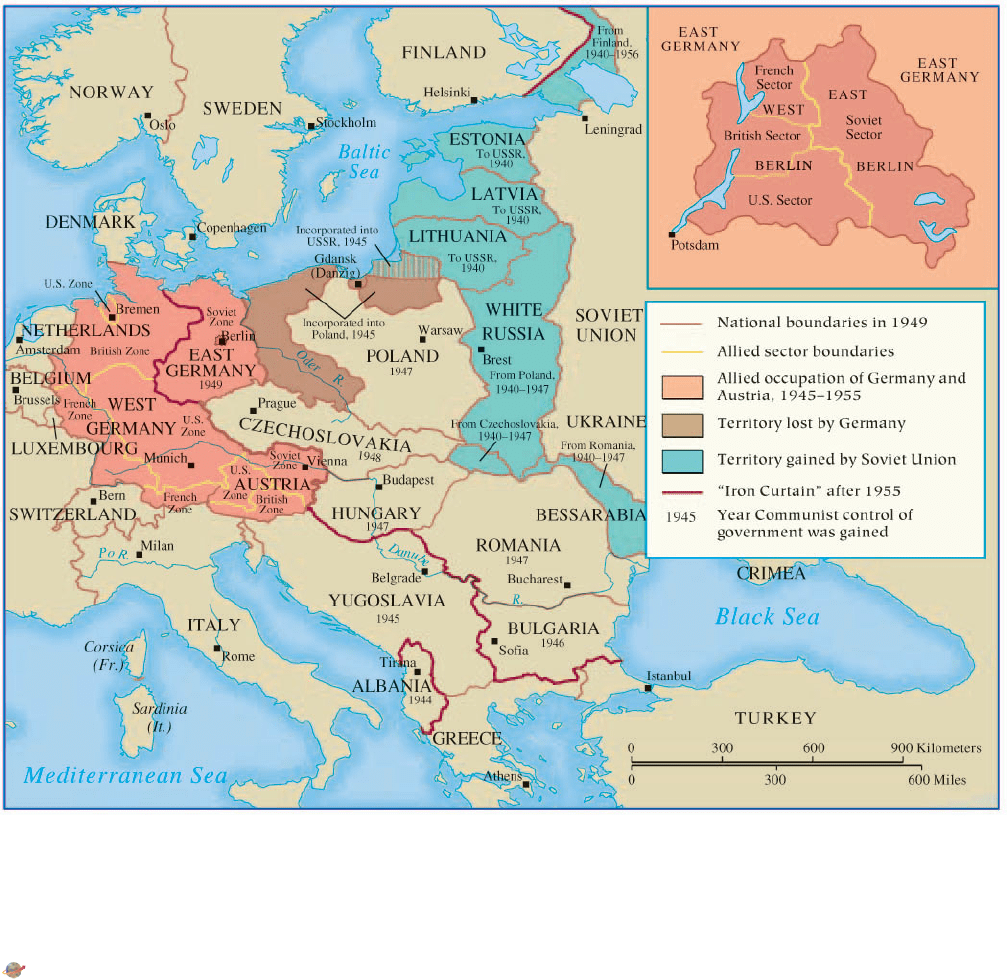

MAP 25.3 Territorial Changes in Europe After World War II. In the last months of World

War II, the Red Army occupied much of eastern Europe. Stalin sought pro-Soviet satellite

states in the region as a buffer against future invasions from western Europe, whereas Britain

and the United States wanted democratically elected governments. Soviet military control of the

territory settled the question.

Q

Which country gained the greatest territory at the expense of Germany?

View an animated version of this map or related maps at www .cengage.com/history/

duikspiel/essentialworld6e

AFTERMATH OF THE WAR 637

By the time of the conference at Yalta in southern

Russia in Februar y 1945, the defeat of Germany was a

foregone con clusion. The Western powers now faced the

reality of 11 million Red Army soldier s taking posses-

sion of large portions of Europe. Stali n, deeply suspi-

cious of the Western powers, desired a buffer to protect

the Soviet Union from possible future Weste rn aggres-

sion but at t he same time was eager to obtain important

resource s and strategic military positions. Roosevelt

by this time was moving toward th e idea of self-

determination for Europe. The Grand Alliance approved

the ‘‘Declaration on Liberated Europe.’’ This was a pledge

to assist liberated European nations in the creation of

‘‘democratic institutions of their own choice.’’ Liberated

countries were to hold free elections to determine their

political systems.

At Yalta, Roosevelt sought Russian military help

against Japan. Development of the atomic bomb was not

yet assured, and American military planners feared the

possible loss of as many as one million men in invading

the Japanese home islands. Roosevelt therefore agreed

to Stalin’s price for military assistance against Japan:

possession of Sakhalin and the Kurile Islands, as well as

railroad rights in Manchuria.

The creation of the United Nations was a major

American concern at Yalta. Roosevelt hoped to ensure the

participation of the Big Three in a postwar international

organization before difficult issues divided them into

hostile camps. After a number of compromises, both

Churchill and Stalin accepted Roosevelt’s plans for a

United Nations organization and set the first meeting for

San Francisco in April 1945.

The issues of Germany and eastern Europe were

treated less decisively. The Big Three reaffirmed that

Germany mus t surrender unconditionally and created

four occupation zones (see Map 25.3 on p. 637). A

compromise was also worked out in regard to Poland.

Stali n agreed to free elections in the future t o determine

a new government. But the issue of free elections

in eastern Europe caused a serious rift between the

Soviets and the Americans. The principle was that east-

ern European governments would be freely elected, but

they were also supposed to be pro-Russian. This attempt

to reconcile two irreconcilable goals was doomed to

failure, as soon became evident at the next conference of

the Big Three.

The Potsdam conference of July 1945 began under

a cloud of mistrust. Roosevelt had died on April 12 and

had been succeeded as president by Harry Truman. At

Potsdam, Truman demanded free elections throug hout

eastern Euro pe. Stalin responded, ‘‘A freely elected

government in any of these East European countries

would be anti-Soviet, and that we cannot allow.’’

10

After a bitterly fought and devastating war, Stalin

sought absolute military security. To him, it could be

gained only by the pre sence of Communist states in

eastern Europe. Free elections might result in govern-

ments hostile to the Soviets. By the middle of 1945,

only an invasion by We stern forces could undo devel-

opments in eastern Europe, and few people favored

such a policy.

As the war slowly receded into the past, the reality of

conflicting ideologies reappeared (see the comparative

essay on p. 634). Many in the West interpreted Soviet

policy as part of a worldwide Communist conspiracy.

The Soviets, for their part, viewed Western---especially

American---policy as nothing less than global capitalist

expansionism or, in Leninist terms, economic imperial-

ism. In March 1946, in a speech to an American audience,

former British prime minister Winston Churchill de-

clared that ‘‘an iron curtain’’ had ‘‘descended across the

continent,’’ dividing Germany and Europe into two hos-

tile camps. Stalin branded Churchill’s speech a ‘‘call to

war with the Soviet Union.’’ Only months after the

world’s most devastating conflict had ended, the world

seemed once again to be bitterly divided.

CONCLUSION

WORLD WAR II was the most devastating total war in human

history. Germany, Italy, and Japan had been utterly defeated. Perhaps

as many as 60 million people---combatants and civilians---had been

killed in only six years. In Asia and Europe, cities had been reduced to

rubble, and millions of people faced starvation as once fertile lands

stood neglected or wasted.

What were the underlying causes of the war? One direct cause was

the effort by two rising powers, Germany and Japan, to make up for

their relatively late arrival on the scene to carve out global empires. Key

elements in both countries had resented the agreements reached after

the end of World War I, which divided the world in a manner favorable

to their rivals, and hoped to overturn them at the earliest opportunity.

In Germany and Japan, the legacy of a past marked by a strong military

tradition still wielded strong influence over the political system and the

mindset of the entire population. It is no surprise that under the

impact of the Great Depression, which had severe effects in both

countries, militant forces determined to enhance national wealth and

power soon overwhelmed fragile democratic institutions.

Whatever the causes of World War II, the consequences were

soon evident. European hegemony over the world was at an end, and

638 CHAPTER 25 THE CRISIS DEEPENS: WORLD WAR II

SUGGESTED READING

The Dictatorial Regimes For a general study of fascism,

see S. G. Payne, A History of Fascism (Madison, Wis., 1996), and

R. O. Paxton, The Anatomy of Fascism (New York, 2004). The best

biography of Mussolini is R. J. B. Bosworth, Mussolini (London,

2002). On Fascist Italy, see R. J. B. Bosworth, Mussolini’s Italy: Life

Under the Fascist Dictatorship (New York, 2006).

Two brief but sound surveys of Nazi Germany are J. J.

Spielvogel, Hitler and Nazi Germany: A History, 5th ed. (Upper

Saddle River, N.J., 2005), and W. Benz, A Concise Histor y of the

Third Reich, trans T. Dunlap (Berkeley, Calif., 2006). The best

biography of Hitler is I. Kershaw, Hitler, 1889--1936: Hubris (New

York, 1999), and Hitler: Nemesis (New York, 2000). On the rise of

the Nazis to power, see R. J. Evans, The Coming of the Third Reich

(New York, 2004), and The Third Reich in Power, 1933--1939 (New

York, 2005).

The collectivization of agriculture in the Soviet Union

is examined in S. Fitzpatrick, Stalin’s Peasants: Resistance and

Survival in the Russian Village After Collectiv ization (New York,

1995). Industrialization is covered in H. Kuromiya, Stalin’s

Industrial Revolution: Politics and Workers, 1928--1932 (New York,

1988). On Stalin himself, see R. Service, Stalin: A Biography

(Cambridge, Mass., 2006), and R. W. Thurston, Life and Terror

in Stalin’s Russia, 1934--1941 (New Haven, Conn., 1996).

The Path to War On the causes of World War II, see

A. J. Crozier, Causes of the Second World War (Oxford, 1997).

two new superpowers had emerged on the fringes of Western

civilization to take its place. Even before the last battles had been

fought, the United States and the Soviet Union had arrived at

different visions of the postwar world, and their differences soon led

to the new and potentially even more devastating conflict known as

the Cold War. And even though Europeans seemed merely pawns in

the struggle between the two superpowers, they managed to stage a

remarkable recovery of their own civilization. In Asia, defeated Japan

made a miraculous economic recovery, while the era of European

domination finally came to an end.

TIMELINE

1925

1930 1935 1940 1945

Europe

Asia

Mussolini creates Fascist

dictatorship in Italy

Stalin’s first

five-year plan begins

Japanese attack

on Pearl Harbor

Conferences

at Yalta and

Potsdam

The Holocaust

Japanese takeover of Manchuria

Kristallnacht

Atomic bomb

dropped on

Hiroshima

Hitler and Nazis come

to power in Germany

Fall of France German defeat

at Stalingrad

Japanese create Ministry

for Great East Asia

CONCLUSION 639

On the origins of the war in the Pacific, see A. Iriye, The Origins of

the Second World War in Asia and the Pacific (London, 1987).

World War II General works on World War II include the

comprehensive study by G. Weinberg, A World at A rms: A Global

History of World War II, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, 2005), and

J . Campbell, TheExperienceofWorldWarII(New York, 1989). For

briefer histories, see J. Plowright, Causes, Course, and Outcomes of

World War II (New York, 2007), and M. J. Ly on, World War II: A

Short History , 4th ed. (Upper Saddle River, N.J., 2004).

The Holocaust Excellent studies of the Holocaust include

R. Hilberg, The Destruction of the European Jews, rev. ed., 3 vols.

(New York, 1985); S. Fried

€

ander, The Years of Extermination: Nazi

Germany and the Jews, 1939--1945 (New York, 2007); and L. Yahil,

The Holocaust (New York, 1990). For brief studies, see J. Fischel,

The Holocaust (Westport, Conn., 1998), and D. Dwork and R. J.

van Pelt, Holocaust: A History (New York, 2002).

The Home Front On t he home front in Germany, see

M. Kitchen, Nazi Germany at War (New York, 1995). The Soviet

Union during the war is examined in M. Harrison, Soviet

Planning in Peace and War, 1938-- 1945 (Cambridge, 1985). The

Japanese home front is examined in T. R. H. Havens, The Valley

of Darkness: The Japanese People and World War Two (New

York, 1978).

On the Allied bombing campaign against Germany , see

R. Neillands, The Bomber War: The Allied Air Offensive Against

Nazi Germany (New York, 2005), and J. Friedrich, The Fire: The

Bombing of Germany, trans. A. Brown (New York, 2006). On the use

of the atomic bomb in Japan, see M. Gordin, Five Days in August:

How World War II Became a Nuclear War (Princeton, N.J., 2006).

Emergence of the Cold War On the emergence of the Cold

War, see L. Gaddis, The Cold War: A New History (New York,

2005); J. W. Langdon, A Hard and Bitter Peace: A Global History

of the Cold War (Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1995); and J. Smith, The

Cold War, 1945--1991 (Oxford, 1998).

Visit the website for The Essential World History to access study

aids such as Flashcards, Critical Thinking Exercises, and

Chapter Quizzes:

www.cengage.com/history/duikspiel/essentialworld6e

640 CHAPTER 25 THE CRISIS DEEPENS: WORLD WAR II

641

PART

V

T

OWARD A

G

LOBAL

C

IVILIZATION

?

T

HE

W

ORLD

S

INCE

1945

26 EAST AND WEST IN THE GRIP

OF THE

COLD WAR

27 BRAVE NEW WORLD:COMMUNISM

ON

TRIAL

28 EUROPE AND THE WESTERN HEMISPHERE

SINCE 1945

29 CHALLENGES OF NATION BUILDING

IN

AFRICA AND THE MIDDLE EAST

30 TOWARD THE PACIFIC CENTURY?

EPILOGUE: AGLOB AL CIVILIZATION

AS WORLD WAR II came to an end, the survivors of that bloody

struggle could afford to face the future with a cautious optimism.

Europeans might hope that the bitter rivalry that had marked relations

among the Western powers would finally be put to an end and that the

wartime alliance of the United States, Great Britain, and the Soviet

Union could be maintained into the postwar era.

More than sixty year s later, these hopes have been only partly

realized. In the decades following the war, the Western capitalist

nations managed to recover from the economic depression that had led

into World War II and adva nced to a level of econo mic prosperity never

seen before. The bloody conflicts that had erupted among European

nations during the first half of the twentieth century came to an end,

and Ge rmany and Japan were fully integrated into the world

community.

At the same time, the prospects for a stable, peaceful world and an

end to balance-of-power politics were hampered by the emergence of a

grueling and sometimes tense ideological struggle between the socialist

and capitalist camps, a competition headed by the only remaining great

powers, the Soviet Union and the United States.

In the shadow of this rivalry, the Western European states made a

remarkable economic recov ery and reached untold levels of prosperity . In

Eastern Europe, Soviet domination, both politically and economically,

seemed so complete that many doubted it could ever be undone. But

communism had never developed deep roots in Eastern Europe, and in

the late 1980s, when Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev indicated that his

government would no longer pursue military intervention, Eastern

European states acted quickly to establish their freedom and adopt new

economic structures based on Western models.

Outside the West, the peoples of Africa and Asia had their own

reasons for optimism as World War II came to a close. In the Atlantic

Charter, Franklin Roosev elt and Winston Churchill had set forth a joint

declaration of their peace aims calling for the self-determination of all

peoples and self-government and sovereign rights for all nations that had

been deprived of them.

As it turned out, some colonial powers were reluctant to divest

themselves of their colonies. Still, World War II had severely undermined

the stability of the colonial order, and by the end of the 1940s, most

colonies in Asia had received their independence. Africa follo wed a decade

or two later .

Broadly speaking, the leaders of these newly liberated countries set

forth three goals at the outset of independence. They wanted to throw off

the shackles of Western economic domination and ensure material

prosperity for all of their citizens. They wanted to introduce new po-

litical institutions that would enhance the right of self-determination of

their peoples. And they wanted to develop a sense of common nation-

hood within the population and establish secure territorial boundaries.

Most opted to follow a capitalist or a moderately socialist path toward

economic development. In a few cases---most notably in China and

Vietnam---revolutionary leaders opted for the Communist mode of

development.

Regardless of the path chosen, the results were often disappointing.

Much of Africa and Asia remained economically dependent on the

642

advanced industrial nations. Some societies faced severe problems of

urban and rural poverty.

What had happened to tarnish the bright dream of economic

affluence? During the late 1950s and early 1960s, one school of thought

was dominant among scholars and government officials in the United

States. Known as modernization theory, this school took the view that the

problems faced by the newly independent countries were a consequence of

the difficult transition from a traditional to a modern society. Moderni-

zation theorists were convinced that agrarian countries were destined to

follow the path of the West toward the creation of modern industrial

societies but would need time as well as substantial amounts of economic

and technological assistance from the West to complete the journey.

Eventu ally, modernization theory began to come under attack from a

new generation of younger scholars. In their view, the responsibility for

continued economic underdevelopment in the developing world lay not

with the countries themselves but with their continued domination by the

ex-colonial powers. In this view , kno wn as dependency theory , the coun-

tries of Asia, Africa, and Latin America were the victims of the international

marketplace, which charged high prices for the manufactured goods of the

West while dooming preindustrial countries to low prices for their own raw

material exports. Efforts by such countries to build up their own industrial

sectors and move into the stage of self-sustaining growth were hampered by

foreign control---through Eur opean- and American-o wned corporations---

over many of their resources. To end this ‘‘neocolonial’’ relationship, the

dependency theory advocates argued, developing societies should reduce

their economic ties with the West and practic e a policy of economic self-

reliance, thereby taking control over their own destinies.

Leaders of African and Asian countries also encountered problems

creating new political cultures responsive to the needs of their citizens.

At first, most accepted the concept of democracy as the defining theme

of that culture. Within a decade, howev er, democratic systems through-

out the developing world were replaced by military dictatorships or one-

party governments that redefined the concept of democracy to fit their

own preferences. It was clear that the difficulties in building democratic

political institutions in developing societies had been underestimated.

The problem of establishing a common national identity has in

some ways been the most daunting of all the challenges facing the new

nations of Asia and Africa. Many of these new states were a composite of a

wide variety of ethnic, religious, and linguistic groups who found it dif-

ficult to agree on common symbols of nationalism. Problems of estab-

lishing an official language and delineating territorial boundaries left over

from the colonial era created difficulties in many countries. Internal

conflicts spawned by deep-rooted historical and ethnic hatreds have

proliferated throughout the world, leading to a vast new movement of

people across state boundaries equal to any that has occurred since the

great population migrations of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

The introduction of Western cultural values and customs has also had

a destabilizing effect in man y areas. Although such ideas are welcomed by

some groups, they are firmly resisted by others. Where Western influence

has the effect of undermining traditional customs and religious beliefs, it

often provokes violent hostility and sparks tension and even conflict within

individual societies. Much of the anger recently directed at the United States

in M uslim countries has undoubtedly been generated by such feelings.

Nonetheless, social and political attitudes are changing rapidly in

many Asian and African countries as new economic circumstances have

led to a more secular worldview, a decline in traditional hierarchical

relations, and a more open attitude toward sexual practices. In part, these

changes have been a consequence of the influence of Western music,

movies, and television. But they are also a product of the growth of an

affluent middle class in many societies of Asia and Africa.

Today we live not only in a world economy but in a world society,

where a revolution in the Middle East can cause a rise in the price of oil in

the United States and a change in social behavior in Malaysia and Indo-

nesia, where the collapse of an empire in Asia can send shock waves as far

as Hanoi and Havana, and where a terrorist attack in New York City or

London can disrupt financial markets around the world.

c William J. Duiker

TOWAR D A GLO B AL CIVILIZATION?THE WORLD SINCE 1945 643