Dobak William A. Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862-1867 (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Along the Mississippi River, 1863–1865

211

met the enemy. On 9 June, the expe-

dition sent four hundred sick and ex-

hausted men—nearly 5 percent of its

strength—and forty-one of the wag-

ons back to Memphis, “all the eating

and non-ghting portion of the com-

mand,” Sturgis called them. Rain fell

for only two hours that day.

55

On the morning of 10 June, the

expedition moved toward Tupelo,

cavalry in the lead. The 55th and

59th USCIs took their turn guarding

the wagon train for the fourth time

since the expedition’s start. They

plodded along, the 55th with four

men assigned to walk beside each

wagon while the 59th USCI and the

two guns of Battery F brought up the

rear. The battery’s horses had been

without corn for two days, but that

morning the commanding ofcer,

Capt. Carl A. Lamberg, had man-

aged to nd a wagonload of fodder

that he thought would last for about

three days. Marching through a part

of Mississippi that had been fought

over for the past two years, the cav-

alry and the wagon teams were in no better shape than the artillery horses. The rear

of the column got under way at about 10:30 and had gone only two miles through

swampy bottom land when Col. Edward Bouton, commanding the rearguard, no-

ticed enemy cavalry traveling a road about a mile to his right. Soon afterward,

he heard the sound of cannon to his front. It came from batteries supporting the

Union cavalry division on the far side of Tishomingo Creek ring on a Confederate

charge that hit the dismounted troopers not long after they crossed the creek and

took up positions east of it.

56

The wagons followed a muddy road through thick pinewoods with only occa-

sional elds opening on either side. It was after 2:00 p.m. before the train crossed

Tishomingo Creek and found a eld large enough to park in, about a quarter-mile

from a crossroads that took its name from William Brice, whose house and store

stood nearby. By that time, Confederate reinforcements had overcome the Union

cavalry. Colonel McMillen rushed an infantry brigade forward to halt the rout, but

he soon saw that “everything was going to the devil as fast as it possibly could.”

The infantry covered the last half-mile “at double-quick . . . , my object being to

55

OR, ser. 1, vol. 39, pt. 1, pp. 88 (quotation), 90–91, 162, 199–200, 207; Cowden, Brief Sketch,

p. 69.

56

OR, ser. 1, vol. 39, pt. 1, pp. 181, 184, 213.

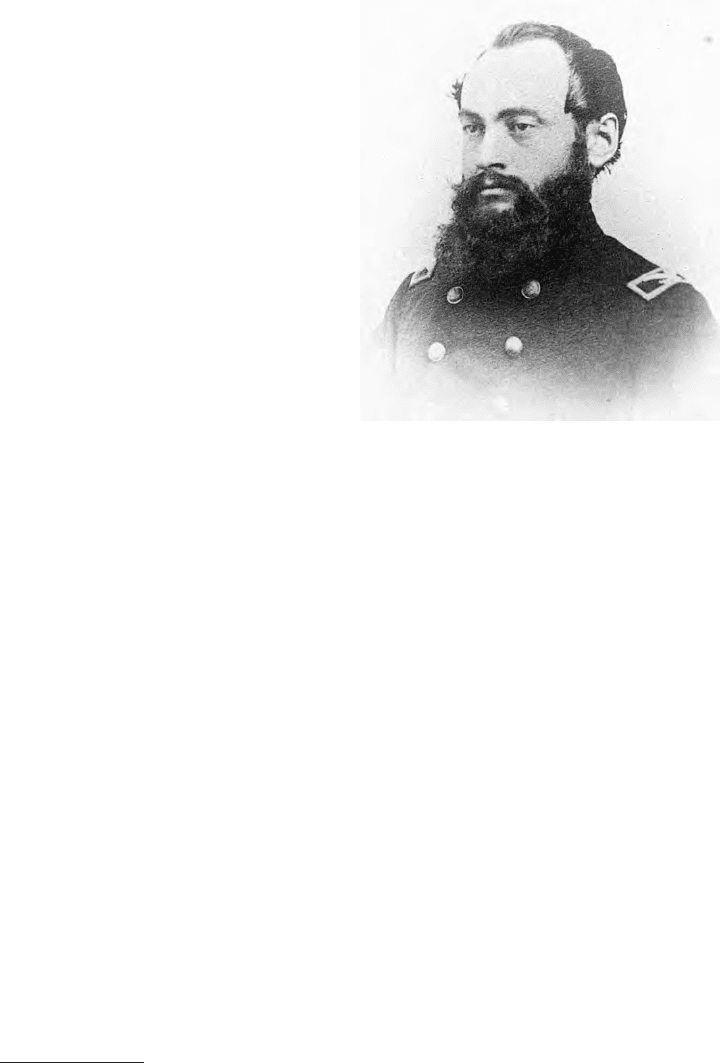

Col. Edward Bouton took care that the

brigade of black troops he led was formed

properly before going into action at Brice’s

Crossroads. As a result, the brigade came

out of that battle in better shape than the

rest of the defeated force and was able to

help cover the Union retreat.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

212

get through [the] retreating cavalry with as little depression as possible to my own

men”; but while the lead brigade was relieving the cavalry that was still on the

ring line, another Confederate charge struck the Union left. Exhausted by the

Mississippi heat and the rapid march, most of McMillen’s men refused to advance

again; he decided to withdraw while he still had some control of them.

57

About that time, the ofcers in charge of the supply train received orders,

before they had nished parking the wagons, to start them on the road again and

join the retreat. Colonel Bouton told the 55th USCI to leave the wagons and form

companies while the 59th joined them from the rear of the column at the double.

No orders had reached Bouton, “but getting a partial view of the eld, and seeing

our cavalry falling back, soon followed by infantry and artillery,” he decided to

act. “I immediately gathered two companies from the head of the column . . . and

threw them forward into what seemed to be a gap in the First Brigade, near the

right and rear of what seemed to be the left battalion.” The phrases “a partial view”

and “seemed to be” show the tenuous nature of a commander’s grasp of facts dur-

ing a battle; the word “confusion” occurs in General Sturgis’ report and in reports

of division, brigade, and regimental commanders. Seven more companies of the

55th soon reinforced the rst two and covered the retreat of the troops on their

right. When the way was clear, the 59th lled the vacant space. Captain Lamberg’s

two cannon red exploding shells over the woods through which the Confederates

were advancing, with orders to substitute canister shot when the enemy came in

view, “which order he obeyed as well as possible until he was forced to retire,”

Bouton reported, “leaving one caisson on the ground, which he was compelled to

do on account of its horses being many of them killed.”

58

It was late afternoon before the Confederates forced Bouton’s brigade out of

its position. The men retired slowly from eld to eld for about half a mile and at

sunset halted on high ground at the edge of some woods. “Our company was in a

skirmish line and we were falling back, for Forrest was crowding us,” Pvt. George

Jenkins of the 55th USCI recalled when he applied for a pension years later. “I

would turn & shoot & then retreat. We were crossing a little opening in a kind of

old eld 200 or 300 y[ar]ds from some woods, when as I turned a bullet struck me

in the right hip & passed clean through & went into the left thigh. I fell like a dead

man & fainted away, I reckon.” The next day, Confederate troops took Jenkins and

other prisoners to Mobile, where a surgeon removed the bullet.

59

In the failing light, the 59th USCI received one last Confederate charge and

chased the attackers back “with bayonets and clubbed muskets,” Bouton reported,

more than half the distance the regiment had just covered. Then Bouton discovered

that while his own men charged, the brigade on his left had continued to retire. By

57

Ibid., pp. 208 (“everything”), 209 (“at double-quick”), 210, 213, 903; George B. Davis et al.,

eds., The Ofcial Military Atlas of the Civil War (New York: Barnes & Noble, 2003 [1891–1895]),

p. 167.

58

OR, ser. 1, vol. 39, pt. 1, pp. 94 (Sturgis), 98, 105 (McMillen), 124 (Lt Col G. R. Clarke, 113th

Illinois), 125 (“but getting”), 126, 129 (Grierson), 145 (Maj A. R. Pierce, 3d Iowa Cav), 213; Cowden,

Brief Sketch, p. 93.

59

Depositions, George Jenkins, 18 Nov 1896 (quotation), and Thomas Kimbrough, 2 Jul 1897,

both in Pension File SC811848, George Jenkins, Civil War Pension Application Files (CWPAF), RG

15, Rcds of the Veterans Admin, NA.

Along the Mississippi River, 1863–1865

213

this time, the eld ofcers of both black regiments were wounded and out of ac-

tion, leaving the senior captains in command, insofar as either regiment retained

any organization at all. The 55th USCI had about 200 men present of 604 that had

gone into action, the 59th about 250 of 607. Bouton decided to retreat. Along the

way, the men of the 59th picked up ammunition that had been thrown away by

stampeding white troops. By 11:00 p.m., when the remnant of Bouton’s brigade

caught up with the rest of Sturgis’ force, the regiment held an average of twenty-

ve rounds per man.

60

This came in handy the next day, for the expedition had lost most of its supplies

on the day of the battle. Panic-stricken teamsters deserted their wagons, setting re to

some of them. Burning and abandoned wagons blocked the federal retreat on the nar-

row, muddy road to Ripley, but once Sturgis’ command had struggled past them, they

delayed the Confederate pursuit as well. The ammunition wagons fell into the hands

of Forrest’s cavalry. Men of the 55th USCI felt the loss keenly the next morning,

when the Confederates caught up with them near Ripley. “As our ammunition was

captured we were unable to stand even a test & made a hasty retreat,” the regiment’s

summary of the expedition recorded at the end of the month. “The enemy came on to

us with cavalry & scattered both ofcers and men all through the woods.”

61

Because of the headlong retreat, casualty lists were largely conjectural. “The

ghting was desperate, and many reported then ‘missing’ were killed on the eld,”

one company commander reported; “but I am unable to tell which ones they were.

I think most of them were killed. . . . But we were obliged to leave our dead and

wounded. . . . Although about 10 wounded have come in [by 30 June] having hid

in the bushes and traveled nights living on berries and bark, and occasionally get-

ting food from colored people in the country. They were annoyed very much by

[civilians] with blood hounds.” Regimental descriptive books for the 55th and 59th

USCIs—volumes that contain each soldier’s record and were kept up-to-date until

the regiments mustered out after the war—show 7 missing men rejoining within a

few days after the battle, 12 rejoining between July and October, and 9 rejoining at

an unnamed or illegible date. Pvt. Claiborne Merriweather of the 59th USCI was last

seen ring a carbine that he had taken from a Confederate whom he had just beaten

to death with the butt of his rie. Left behind in the retreat, Merriweather did not turn

up again for seven weeks. Pvt. Henry Guy had to escape from his captors twice, the

rst time from the hospital where a Confederate surgeon treated his wounds, before

he was able to rejoin the 55th USCI at La Grange, Tennessee, late in August.

62

At least nineteen of Guy’s comrades waited until the war was over to rejoin.

These men had been taken prisoner and put in hospitals to recover from their wounds

or sent to Mobile to work on the city’s fortications when Union forces occupied its

seaward approaches in August. After the forts on the eastern shore of Mobile Bay

fell in April 1865, the prisoners moved north to Montgomery, where they stayed

until after Confederate troops in the region surrendered the next month. Most of the

60

OR, ser. 1, vol. 39, pt. 1, p. 126 (quotation), 904; Cowden, Brief Sketch, pp. 98–99.

61

OR, ser. 1, vol. 39, pt. 1, pp. 115, 224; NA M594, roll 211, 55th USCI.

62

NA M594, roll 211, 55th USCI (“the ghting”); Regimental Books, 55th and 59th USCIs,

RG 94, NA; Declaration, Henry Guy, 7 Apr 1885, and Afdavit, Henry Guy, 27 Feb 1886, both in

Pension File WC571997, Henry Guy, CWPAF.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

214

prisoners rejoined their regiments in June. At least ve men died while prisoners of

war. Undoubtedly, many more dead were among the 153 men still listed as missing

when the regiments closed their descriptive books. Some of these died in the ghting

of June 1864 and were left on the eld in the Union forces’ rapid retreat, but only Pvt.

Balam Fenderson’s name bears the notation “shot Death, after Surrender.” At least

eight of the returned prisoners of war received treatment in Confederate hospitals.

As sketchy as the statistics are, they show that the Union defeat in June 1864 was not

a massacre of the kind that had occurred two months earlier, even though part of the

Confederate force in Mississippi had carried out the slaughter at Fort Pillow.

63

The rout of Sturgis’ force was a triumph for Forrest’s aggressive tactics. The

Union force included ten white infantry regiments that had been in the eld for

more than a year and a half. Many of the men were veterans of the previous year’s

Vicksburg Campaign. These regiments had practically dissolved before the charging

Confederates. Ofcers reported scenes of disorder, with men destroying or throwing

away their weapons and hiding in the woods or running to keep up with the retreat-

ing cavalry. “The infantry being thus left . . . with no ammunition, exhausted with

more than twenty-four hours’ constant exertion without rest or food, many of them

became an easy prey to the enemy,” the commanding ofcer of the 81st Illinois re-

ported. Ofcial correspondence contains only occasional mentions of resistance by

the retreating federals: two companies of the 3d Iowa Cavalry “checked the rebel

advance” at one point, and the 113th Illinois reported skirmishing “almost the entire

distance” back to Collierville, Tennessee. Colonel McMillen’s report praised Colo-

nel Bouton’s regiments repeatedly. Their action late in the day at Brice’s Crossroads

“checked the pursuit and ended the ghting for that evening.” At Ripley the next

morning, they “fought bravely” before being “overpowered by superior numbers.”

They “fought with a gallantry that commended them to the favor of their comrades

in arms.” Unfortunately for them and their white comrades, gallantry was not enough

to save the expedition.

64

At camps around Memphis, Union soldiers watched the expedition’s survivors

straggle in. Sturgis and his staff appeared on 13 June. The rest of the defeated

force began to arrive the next day. “The army is badly demoralized,” Lieutenant

Buswell wrote. “Some of the boys in order to run with ease . . . threw [their ries]

& cartridge boxes into the swamp. . . . The colored boys were praised by every

63

Afdavit, Henry Guy, 27 Feb 1886, in Pension File WC571997, Guy. Depositions, Sandy

Sledge, in Pension File SC172409, Ruben Hogan; George Jenkins, 18 Nov 1896, in Pension File

WC811448, George Jenkins; Thomas Kimbrough, 29 Apr 1899, and Jordan Watson, 29 Apr 1899,

both in Pension File WC430651, Gus Price. Afdavit, Armstead Rann, 30 Aug 1892, in Pension File

SO1119709, Armstead Rann; Declaration, Reuben Stafford, 26 Dec 1895, in Pension File WC930742,

Reuben Stafford; all in CWPAF. Descriptive Book (“shot Death”), 59th USCI, Regimental Books,

RG 94, NA. George S. Burkhardt, Confederate Rage, Yankee Wrath: No Quarter in the Civil War

(Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2007), pp. 152–57, alleges that the Confederates

massacred black soldiers at Tishomingo Creek, just as they did at Fort Pillow. Reasons for different

Confederate behavior at different times and places must remain speculative to a degree, as in all

wars. Simon Sebag-Monteore, Dunkirk: Fight to the Last Man (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard

University Press, 2006), pp. 356–60, tells of a British soldier who was rescued by German medics

after being wounded a little while earlier by the SS (Schützstaffel), who carried out a massacre of

prisoners.

64

OR, ser. 1, vol. 39, pt. 1, pp. 106 (McMillen), 112 (3d Iowa Cav, 93d Indiana), 116 (72d Ohio),

120 (113th Illinois), 123 (81st Illinois).

Along the Mississippi River, 1863–1865

215

soldier for their valor & bravery. In the ght colored soldiers were taken prisoners

and paroled same as others.” Two days later, Buswell added: “More of the soldiers

from the . . . expedition came in today having dodged around from place to place,

their only friends being the blacks, who fed them.”

65

In their haste to get away, Sturgis’ troops retreated in two days the same dis-

tance they had taken almost a week to cover while advancing. Perhaps the roads of

northern Mississippi had dried a little; certainly, the expedition was no longer en-

cumbered by its baggage wagons, which were in Confederate hands. In Memphis,

General Washburn received Sturgis’ rst message of defeat on 12 July. Washburn

at once sent a telegram to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. He estimated that

Sturgis had lost one-quarter or half of his expedition, but “with troops lately ar-

rived [at Memphis] I am safe here.” General McPherson, commanding the Army of

the Tennessee, had ordered the expedition, Washburn said; “an ofcer sent me by

General Sherman” had carried it out. He sent a less craven, blame-shifting message

to Sherman, asking whether Maj. Gen. Andrew J. Smith’s recently arrived divi-

sions should carry out Sherman’s idea of an offensive against Mobile.

66

Sherman replied by telegram from Big Shanty on the railroad north of Mari-

etta, Georgia. Postpone the Mobile Expedition, he advised Washburn, and send

Smith’s force after Forrest and whatever other Confederates remained in Missis-

sippi. “They should be met and defeated at any and all cost.” Smith’s men were

veterans of the Army of the Tennessee. They had marched to Meridian in January,

after which Sherman sent them to augment Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks’ Red

River Expedition. With that campaign over, they had just landed at Memphis on

their way east to join the attack on Atlanta, but Sherman was willing to spare them

a while longer in order to defeat Forrest and thus protect his army’s vital rail line

to Nashville from Confederate raids.

67

As Smith prepared to move, General Washburn sent Colonel Bouton and his

brigade east to guard the forty-mile stretch of the Memphis and Charleston Rail-

road that ran as far as La Grange, Tennessee, where the expedition would assem-

ble. When Smith’s force had arrived there, Bouton’s nineteen hundred men would

join it to make a total of about fourteen thousand infantry, cavalry, and artillery.

Reorganized after Sturgis’ expedition, Bouton’s brigade included, besides his own

59th, the 61st and 68th USCIs and Battery I, 2d USCA. Some companies of the

61st had been in action at Moscow, Tennessee, the previous December; the 68th

had mustered in only that April.

68

The troops left Memphis in freight cars. Instructions for the move called for

“light marching order.” At La Grange, Lieutenant Buswell found “not a tent in

the entire command, except a few ies for Hd Qrs . . . and each regiment, and the

Commissary Dept. The men rolling up in their rubber blankets and lying upon the

ground. . . . It is certainly ghting trim throughout, no luggage of any descrip-

tion, except the men have their haversacks & canteens . . . not even a change of

underclothing.” General Smith believed in the kind of campaigning that his men

65

Buswell Jnls, 14 and 16 Jun 1864.

66

OR, ser. 1, vol. 39, pt. 2, p. 106.

67

Ibid., p. 115.

68

Ibid., pt. 1, pp. 250, 300.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

216

had carried on for the past two years in Tennessee and Mississippi, and, earlier in

1864, in Louisiana.

69

On 5 July, the expedition set out. Buswell noticed that the 59th USCI burned

deserted houses along the route, claiming that the residents had red on Union troops

during the recent retreat. The 59th “and the Kansas Jay hawkers . . . burned the entire

town” of Ripley, Mississippi, he noted on 8 July, “except three buildings, the occu-

pants of which were friendly to our wounded boys” on the retreat. Smith’s command

continued for the next three days by what Colonel Bouton called “easy marches,”

short distances made necessary by heat and drought. The expedition halted on 12

July at Pontotoc, while cavalry scouted the roads that led southeast to Okolona and

due east to Tupelo, two stations on the Mobile and Ohio Railroad. Finding a Confed-

erate force on the Okolona road, Smith decided to move toward Tupelo.

70

Drummers beat reveille at 3:00 on the morning of 13 July. Smith’s cavalry be-

gan moving before dawn, but it was 6:00, an hour after sunrise, before Bouton’s

brigade took the road at the tail of the column. By turning toward undefended Tu-

pelo, rather than confronting Forrest’s force at Okolona, Smith left the expedition’s

rear exposed to Confederate attack. He protected the wagon train by assigning ve

regiments of veteran white infantry—perhaps fteen hundred men, a considerable

addition to Bouton’s three regiments—to guard it. About four men marched beside

each wagon.

71

The train had been on the road for barely an hour when Forrest’s artillery began

shelling the wagons. Bouton ordered the 59th USCI, the 61st USCI, and Battery

I into line to repel the Confederate cavalry. Farther along the road, he organized

several ambushes of about one hundred men each hidden in dense underbrush that

allowed the enemy to approach within a dozen or so paces without discovering them.

“Fighting in the manner I did,” Bouton remarked, “with my men concealed and un-

der cover, I was able to punish the enemy pretty severely and suffer comparatively

no loss.” Firing continued all day long. Toward nightfall, the two infantry regiments

became so tired that Bouton had to send the untried 68th USCI into action. The

thickly wooded country through which the road to Tupelo passed gave little room

for mounted maneuvers and limited gunners’ vision, so the Confederate pursuit was

able to do little damage. Bouton’s brigade suffered one man killed, seven wounded,

and nine missing. The train did not reach Tupelo until 9:00 p.m., well after dark.

72

Bouton’s Confederate opponents admitted that the federal troops that day fought

better than they had in June. “At no time had I found the enemy unprepared,” the

Confederate Brig. Gen. Abraham Buford reported, summing up the day’s events.

“He marched with his column well closed up, his wagon train well protected, and

his anks covered in an admirable manner, evincing at all times a readiness to meet

69

Buswell Jnls, 2 Jul 1864; Cowden, Brief Sketch, p. 126 (“light marching”). On XVI Corps

troops in Banks’ Red River Campaign, see Chapter 4, above.

70

OR, ser. 1, vol. 39, pt. 1, pp. 250–51; Buswell Jnls, 6 and 8 Jul 1864. Many senior ofcers,

Union and Confederate, complained of the heat and its effect on their men. OR, ser. 1, vol. 39, pt.

1, pp. 253, 260, 275, 281, 287, 289, 300 (quotation), 308, 311, 326, 331–32, 336, 338, 340–41, 343,

349, 351.

71

OR, ser. 1, vol. 39, pt. 1, pp. 276, 301; Buswell Jnls, 13 Jul 1864.

72

OR, ser. 1, vol. 39, pt. 1, pp. 302 (quotation), 905–06; Cowden, Brief Sketch, pp. 127–28.

Along the Mississippi River, 1863–1865

217

any attack, and showing careful generalship.” It is not clear whether he referred to

General Smith’s management of his entire force, or to Bouton’s rearguard action.

73

Smith’s cavalry had covered the eighteen miles from Pontotoc to Tupelo by noon

on 13 July; by midafternoon, the destruction of the Mobile and Ohio Railroad was

well under way. The Union force had now gotten between the Confederates and the

railroad. While the cavalry tore up the tracks and burned bridges and trestles for sev-

eral miles on either side of Tupelo, the two infantry divisions and Bouton’s brigade

halted a mile or two west of town on either side of the road they had traveled that day.

The Confederate department commander, Lt. Gen. Stephen D. Lee, who had joined

Forrest a week earlier with a small force of infantry, ordered an assault on the Union

position for the next morning, 14 July.

74

Bouton’s brigade occupied high ground on the left of the Union line, two-thirds

of a mile south of the road. The position was far from the main thrust of the Con-

federate advance, but it afforded an excellent view. “About 7 A.M. skirmishing was

heard along the line,” Lieutenant Buswell recorded in his diary. West of the Union

camp stood a stone wall, and beyond it an abandoned cotton eld, perhaps one mile

by three quarters, and beyond that woods. Six batteries of six guns each took station

in the eld. “The troops were ordered to keep close down and keep quiet behind the

stone wall,” Buswell wrote.

Soon the rebs were seen coming through the timber . . . and the batteries com-

menced ring. . . . They came out into the clearing 3 divisions, 3 lines deep, dis-

mounted, their leader, who we learned was Chalmers, riding back and forth behind

their ranks, on a noble white charger, his hat in one hand and sword swinging in the

other, cheering on his men. . . . [T]heir ranks were mown through & through, but

they charged and charged, until nearly up to the cannon, when orders were given to

our forces to re, when we arose from behind the wall & fence and met them face

to face. It was desperate, they came on with many a cheer and occasionally a rebel

yell, their losses were tremendous. . . . [T]hey . . . were nally compelled to give

way, and back they fell across the eld. . . . The [Union] troops . . . remained in line

of battle all day, and orders were rec’d to remain so all night, our coffee & hard tack

being brought to us on the line.

75

Heat may have accounted for as many Confederate casualties as did federal

gunre. “These two causes of depletion left my line [of battle] almost like a line

of skirmishers,” one of Forrest’s brigade commanders complained. Another colonel

reported that his regiment suffered 25 percent casualties “through exhaustion and

overheat.” The oppressive weather likewise kept Smith’s men from pursuing the re-

treating Confederates.

76

About sunset, Bouton shifted the bulk of his brigade north in order to shorten

the Union line. The new campsite was some seven hundred yards closer to the

road, at the base of the rise the troops had held throughout the day. The brigade left

73

OR, ser. 1, vol. 39, pt. 1, p. 330.

74

Ibid., pp. 306, 312, 316.

75

Buswell Jnls, 14 Jul 1864.

76

OR, ser. 1, vol. 39, pt. 1, pp. 252, 338 (“through exhaustion”), 349 (“These two”).

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

218

“a heavy skirmish line” in its old position. Not more than two hours passed before

Forrest led a brigade of mounted Confederates “meandering through the woods”

and quietly approached the Union pickets. Lieutenant Buswell was in the camp

below. “The enemy not knowing our true position . . . failed to lower the muzzles

of their guns sufciently to do us any special harm,” he recorded in his diary,

Though we were . . . near enough to distinctly hear the commands of their of-

cers. . . . It was a very dark night and the re from cannon and their lines of

musketry . . . was a sight terrible to behold. . . . Up to this time very little damage

was done [to] our line, quiet was maintained, not a shot on our side, except from

distant batteries while the rebs were advancing down the slope. When they got

sufciently near, so that they could be distinguished . . . , orders were sent along

our lines to commence ring rapidly and at the same time to advance. Our lines

were quite close and the contest for a time was hot. When the rebs fell back, we

following . . . until they went down the hill the other side, into the timber, and

ceased ring.

77

In the darkness, Union soldiers could only conjecture the enemy’s loss, but

Buswell thought that it must have been “considerable. . . . Our own loss was not

very severe.” Despite what Forrest himself called “one of the heaviest res I have

heard during the war,” Confederate casualties were small. Forrest reported no

deaths in his command that evening, “as the enemy overshot us, but he is reported

as having suffered much from the re of my own men, and still more from their

own men, who red into each other in the darkness of the night.” Wild overesti-

mates of enemy strength and casualties characterized reports of ofcers on both

sides throughout the war.

78

On the morning of 15 July, General Smith learned that half of his expedition’s

hardtack had spoiled before it was loaded on the wagons at Memphis and that only

one day’s supply remained. Moreover, the artillery had exhausted its reserve am-

munition the day before, and the only rounds left were those in each gun’s caisson.

Smith therefore decided to withdraw without doing Forrest further harm. Seeing

the federal retreat, the Confederates followed closely and by midmorning caught

up with Bouton’s brigade, which was guarding the supply wagons. Along with

several regiments from one of the white divisions, men of the brigade repelled

this attack in a two-hour skirmish. Late that afternoon, they charged the height

from which they had watched the previous day’s ght and drove off a Confederate

battery that threatened the retreat. From there, the road was clear to La Grange,

Tennessee, the expedition’s starting point. Foraging desperately along the way, the

troops reached there on 21 July and were back in their old camps at Memphis a

day or two later.

79

Despite the need to cut the campaign short for want of rations and ammunition,

Union ofcers were satised with its result and with their troops’ performance.

“Forrest, though he likes a good ght, had got more than he bargained for this

77

Ibid., pp. 303 (“heavy skirmish line”), 323(“meandering”); Buswell Jnls, 14 Jul 1864.

78

OR, ser. 1, vol. 39, pt. 1, p. 323 (Forrest); Buswell Jnls, 14 Jul 1864.

79

OR, ser. 1, vol. 39, pt. 1, pp. 252, 303, 323; Buswell Jnls, 15–23 Jul 1864.

Along the Mississippi River, 1863–1865

219

time,” Lieutenant Buswell recorded in his diary. “Smith gave Forrest the rough-

est handling he has had for a long time,” 1st Lt. Samuel Evans of the 59th USCI

told his father. An interesting feature of Confederate accounts of the ghting is

that only one report mentions the presence of “negroes” in the Union ranks. The

reason cannot have been the effectiveness of Bouton’s troops’ concealment in their

ambushes, for they were in plain sight earlier in the day. They had not been the

object of the main attacks on 14 July, which most Confederate reports emphasized.

After the battle, the Union force withdrew with its 559 wounded (48 in Bouton’s

brigade), and only 38 federal soldiers were missing (16 from the 61st USCI), so

incidents of killing the wounded and returning prisoners to slavery, or setting them

to work on fortications did not occur and require explanation. Perhaps, too, the

Confederate commanders had other matters on their minds after the battle: for in-

stance, the necessity of explaining away their lack of success against a Union force

in which one-seventh of the soldiers were black.

80

No sooner were General Smith’s regiments back in Memphis, properly fed

and with their stock of ammunition replenished, than General Washburn ordered

them after Forrest again. Smith’s force, including Bouton’s brigade, returned to La

Grange by rail and set out for Holly Springs, Mississippi, on 4 August. Sherman’s

instruction was to “take freely of all food and forage,” and the command helped

itself to whatever still grew in northern Mississippi after more than two years of

warfare: corn, potatoes, and fruit. The troops endured much rain but little ghting.

On 22 August, the day Bouton’s brigade reached Oxford, Smith learned the reason

he had not found many Confederates: Forrest, with two thousand men, had raided

Memphis the day before, intending to kill or capture Union commanders there. He

did not succeed but left town with more than one hundred other prisoners. Smith’s

expedition turned north, hoping to block Forrest’s retreat. Bouton’s brigade was

back in Memphis on 1 September, having covered fty miles in the previous two

days—“some tall marching,” as Lieutenant Evans told his father.

81

The Oxford expedition marked the end of major infantry operations in which

U.S. Colored Troops from the Mississippi River garrisons took part. In Georgia,

Sherman’s army occupied Atlanta at the beginning of September. Preparations for

the March to the Sea—no one yet knew whether it would end at Mobile, Pensacola,

or Savannah—took up the next two months. Confederate raiders, Forrest among

them, busied themselves meanwhile in northern Alabama and Mississippi and in

Tennessee. Sherman, who had overall direction of Union armies from the Appa-

lachians to the Mississippi, issued instructions at the end of October. “Don’t be

concerned on the river,” he wrote from northern Georgia to Maj. Gen. Napoleon

J. T. Dana at Memphis. The enemy “cannot make a lodgment on the Mississippi.

. . . He cannot afford to attack forts or men entrenched, for ammunition is scarce

with him, and all supplies. . . . He will be dependent on the Mobile and Ohio [Rail]

road, which should be threatened on its whole length. . . . Give these ideas to all

80

OR, ser. 1, vol. 39, pt. 1, pp. 255–56, 330; Buswell Jnls, 16 Jul 1864; S. Evans to Dear Father,

24 Jul 1864, Evans Family Papers, Ohio Historical Society, Columbus.

81

OR, ser. 1, vol. 39, pt. 1, p. 471, and pt. 2, pp. 201, 221, 233 (“take freely”); Buswell Jnls, 9–22

Aug 1864; S. Evans to Dear Father, 1 Sep 1864, Evans Family Papers.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

220

your river posts. Don’t attempt to hold the interior further than as threatening to

[Confederate] lines of supply.”

82

Unlike U.S. Colored Troops infantry and artillery regiments, which stayed

close to their river-town garrisons during the last ten months of the war, the

only black cavalry regiment in the region, the 3d United States Colored Cavalry

(USCC), remained active. During the last half of 1864, it was continually in the

eld taking part in several expeditions that illustrate clearly the nature of warfare

in a military backwater. The intention of most of these expeditions was to assist

Union operations in other parts of the South or to impede the enemy’s.

During the rst week of July, the 3d USCC was part of an otherwise white

force of 2,800 infantry and cavalry that marched from Vicksburg to Jackson

to destroy a railroad bridge over the Pearl River. General Sherman in north-

ern Georgia had read in an Atlanta newspaper that the bridge was being rebuilt

since Union troops had last visited the site and recommended a weekly expedi-

tion against some part of the Mississippi Central Railroad, “breaking it all the

time, and especially should that bridge at Jackson be destroyed.” The expedition

reached Jackson and destroyed the bridge, but Confederate opposition inicted

two hundred fty casualties. The 3d USCC lost eight ofcers and men killed and

ten enlisted men wounded. On 11 July, a few days after reaching the Big Black

River and replenishing its supplies, the expedition turned east again and spent

the next few days marching to Grand Gulf by way of Raymond and Port Gib-

son, a move intended to support General Smith’s Tupelo Campaign by keeping

Confederates in southwest Mississippi from joining Forrest in the northern part

of the state. From Grand Gulf, the troops returned to Vicksburg by steamboat on

17 July, by which time Smith’s troops had found Forrest, beaten him, and begun

their return to Memphis.

83

The next nine weeks were comparatively quiet around the Mississippi River

garrisons, but in the second half of September, the 3d USCC began a period of

intense activity that lasted until the end of November. In September, the Con-

federate General John B. Hood reacted to Sherman’s capture of Atlanta, rst by

attacks in northern Georgia on Sherman’s supply line to Chattanooga, then by

a withdrawal into Alabama to begin preparing his own move against the Union

garrison and shipping point at Nashville, still farther in the Union rear. Hood’s

subordinate, Forrest, operated meanwhile in support of the larger Confederate

force. Once again, events taking place elsewhere determined the shape of affairs

along the river.

On 19 September, the Union general in command at Natchez reported that a

Confederate force that he had thought might be advancing to attack him “was but

a portion of Forrest’s command visiting this section for supplies.” The 3d USCC

conducted one of several raids by federal troops that week to deprive the enemy

of food and forage in southwestern Mississippi. A month earlier, Colonel Os-

band had assumed command of the District of Vicksburg’s entire cavalry force:

ve regiments with a combined strength of perhaps two thousand. He sent three

82

OR, ser. 1, vol. 39, pt. 3, pp. 527–28.

83

Ibid., pt. 1, p. 243, and pt. 2, p. 151 (“breaking it”); Main, Third United States Colored

Cavalry, p. 177.