Daniell C. Death and Burial in Medieval England, 1066-1550

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Studies on a modern population have shown that in only approximately

16 per cent of cases is the bone affected, and that in over half the cases

the ribs were affected (Stroud and Kemp 1993:223). Tumours

(technically called neoplasia) are not commonly found in archaeological

contexts and, when they are, they are normally benign. Although

interesting in themselves, there are few conclusions that can yet be

drawn from them.

Whereas tumours can reveal little about external influences, diet can

have a dramatic effect upon the skeleton and can show evidence of

dietary trauma (such as famine) or nutritional deficiencies. Rickets (see

above), is caused by a lack of vitamin D, and iron deficiency in the diet

has been widely recognised. Iron deficiency causes pitting to certain

bones (pitting of the orbit of the skull is called ‘cribra orbitalia’; to the

femur ‘cribra femora’; to the vault of the skull ‘parietal osteoporosis’).

Documentary research has suggested that iron deficiency, leading to

chronic anaemia, was widespread in the Middle Ages, as were parasitic

infections which aggravated the conditions (White 1988: 41–2).

One of the most useful indicators of diet is the mouth, and especially

the teeth. Differences in the coarseness of the food results in different

rates of attrition—gritty bread causes the teeth to wear down whilst soft,

refined food produces little attrition but may cause a build-up of

calculus. Chewing harder or more sinewy meat or food also reduced the

build-up of calculus. Sometimes different areas of one cemetery may

highlight the differences in diet, either between social groups or through

time. At St Andrew’s, York, the tenth to twelfth-century burials were

described as having ‘a fairly coarse unvaried diet of sinewy meat and

fibrous vegetables’, whereas the twelfth to fifteenth-century burials—

some of whom may have been monks—were described as having a

softer diet with less sinewy meat and more variety of vegetables and

cereals (Stroud and Kemp 1993:247). In at least one case the teeth may

also indicate that an ill child was cared for with a special diet for some

time, as calculus built up on the teeth indicated that this child was fed

with a soft diet for quite some time before death (Stroud and Kemp

1993:247).

A long time-span can also highlight changes in diet. At Rivenhall

there was a marked increase in caries and abscesses from the Saxon to

medieval population, which, it was argued, showed a change in diet that

caused a shift from alkaline mouth conditions to acid mouth conditions,

probably as a result of increased carbohydrate intake (for example from

sugars) or changing micro-organisms, or a combination of both

(O’Connor 1993: 100). Erosion of tooth enamel may also indicate some

DEATH AND BURIAL IN MEDIEVAL ENGLAND 131

aspects of health: stomach acid being vomited causes erosion, most

commonly seen in modern times through bulimia. At St Andrew’s,

York, one burial produced evidence for this which may have been

caused either by a hiatus hernia or some digestive problem (Stroud and

Kemp 1993:244). Some degree of pain can be determined from the state

of the teeth. When cystic cavities (sacs containing fluid, gas or tooth) press

on nerves, tingling, numbness or pain may result. Sometimes a more

serious development occurs where an abscess breaks through into the

sinus of the upper jaw (maxillary antrum) which could lead to severe

pain, infection or possibly death (Stroud and Kemp 1993:244).

The information that can be acquired from the body is now immense,

and a far cry from the position cited in the 1960s. New scientific

techniques are rapidly developing which allow a greater understanding

of decomposition and trauma. The long-term aim of this research must

be to bring out general points about life and conditions in the past. At the

moment only about thirty excavations have taken place in English

medieval cemeteries, of which about ten have more than a hundred

bodies. Fewer still have been comprehensively published. The results are

of great interest but as yet only allow a preliminary local picture to be built

up. Further publication of the results from large cemetery excavations is

awaited with interest, but for the vast majority of cemeteries across

England the raw data will remain below ground, perhaps forever.

132 THE BODILY EVIDENCE

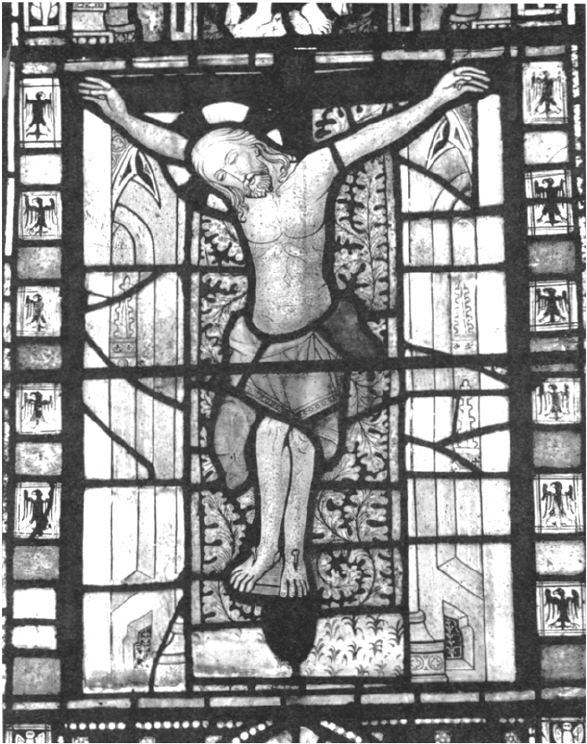

Plate 1 Crucified Christ, West Tanfield, North Yorkshire

(copyright of Dr A Finch, by permission of the Warden of West Tanfield)

DEATH AND BURIAL IN MEDIEVAL ENGLAND 133

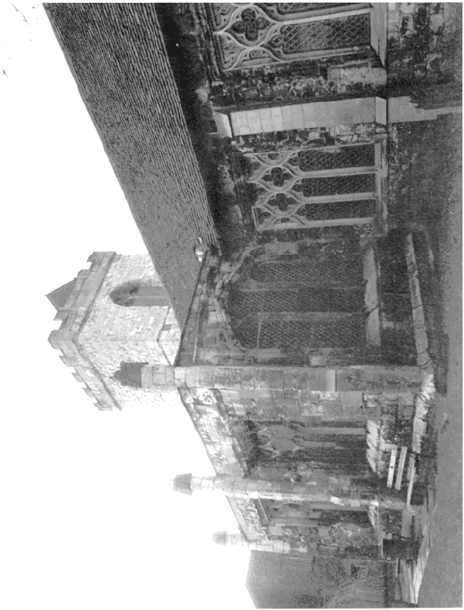

Plate 2 Chantry chapel, Holy Trinity, Goodramgate, York

(copyright of Dr A Finch, by permission of the Friends of Holy Trinity,

Goodramgate)

134 THE BODILY EVIDENCE

Plate 3 Detail of angel from the Marmion tomb, West Tanfield, North Yorkshire

(copyright of Dr A Finch, by permission of the Warden of West Tanfield)

DEATH AND BURIAL IN MEDIEVAL ENGLAND 135

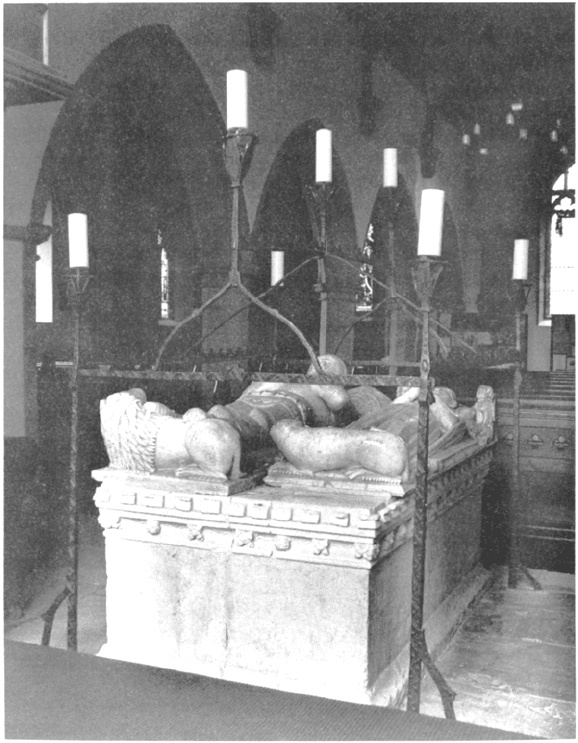

Plate 4 The Marmion tomb and hearse, West Tanfield, North Yorkshire

(copyright of Dr A Finch, by permission of the Warden of West Tanfield)

136 THE BODILY EVIDENCE

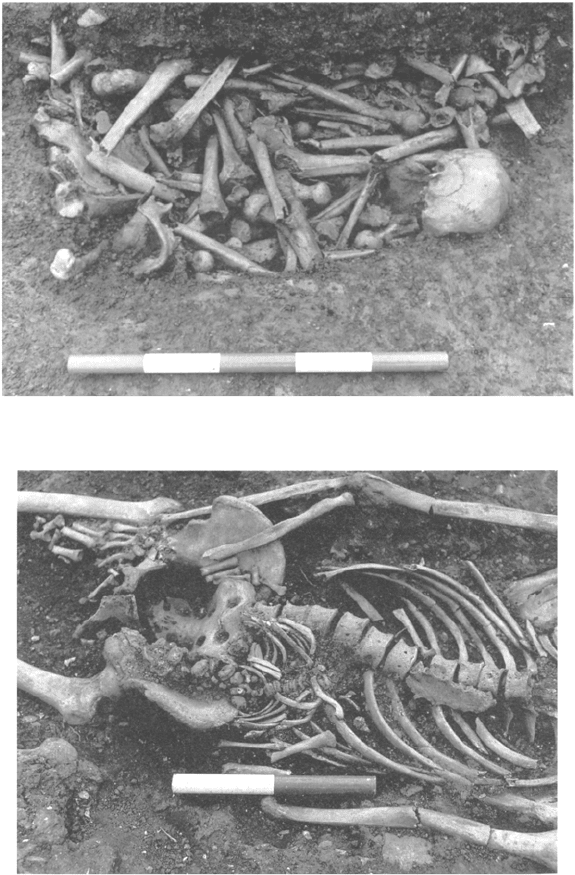

Plate 5 Group of skeletons, showing the compact nature of Christian churchyard

burial, St Helen-on-the-Walls, York

(copyright of York Archaeological Trust)

DEATH AND BURIAL IN MEDIEVAL ENGLAND 137

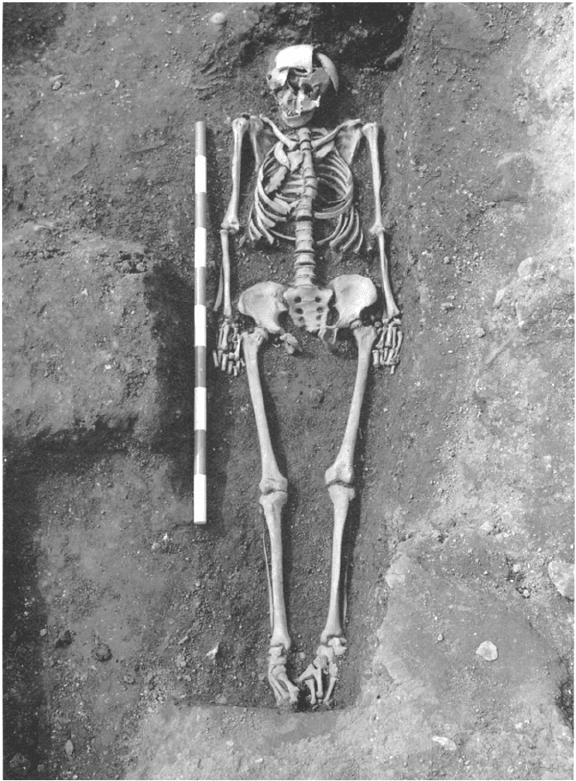

Plate 6 Skeleton of a woman, St Helen-on-the-Walls, York

(copyright of York Archaeological Trust)

138 THE BODILY EVIDENCE

Plate 7 Charnel pit, St Helen-on-the-Walls, York

(copyright of York Archaeological Trust)

Plate 8 Burial of a woman with child of about nine months, St Helen-on-the-

Walls, York

(copyright of York Archaeological Trust)

DEATH AND BURIAL IN MEDIEVAL ENGLAND 139

Plate 9 Decapitated man, buried with large cobbles cradling the skull, St

Andrew’s Priory, Fishergate, York

(copyright of York Archaeological Trust)

140 THE BODILY EVIDENCE