CIMA E1 Official Learning System - Enterprise Operations Aug 2009

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

This page intentionally left blank

3

1

LEARNING OUTCOMES

This part of the syllabus attracts a 20 per cent weighting and covers recent trends in

the global business environment. By completing this chapter you should be assisted in

your studies and better able to:

䉴 explain the emergence of major economies in Asia and Latin America;

䉴 explain the emergence and importance of outsourcing and offshoring;

䉴 explain the impact of international macroeconomic developments (e.g. long-term

shifts in trade balances), on the fi rm’s organisation’s competitive environment;

䉴 explain the principles and purpose of corporate social responsibility and the princi-

ples of good corporate governance in an international context;

䉴 analyse relationships among business, society and government in national and

regional contexts;

䉴 apply tools of country and political risk analysis;

䉴 discuss the nature of regulation and its impact on the fi rm.

1.1 Introduction

Today’s global managers are expected to possess entrepreneurial qualities beyond those of

judgement, perseverance and knowledge of business. Above all, global managers must have

an understanding of the complexities of the modern world and how to deal with people

from a wide range of backgrounds and cultures.

Enormous changes are taking place in the world of business, whether it is the rise of

China and India or the decline of Europe. International fi nance has become more com-

plex. Not only do global managers have to contend with the technicalities of raising and

managing global fi nance, but they have to work with a huge range of labour, environmen-

tal, legal, ethical, social and governance issues for which many are ill equipped.

The real issue facing many of today’s global leaders is what to say about corporate gov-

ernance when the rules and expectations of society are changing so quickly. What do you

The Global Business

Environment

STUDY MATERIAL E1

4

THE GLOBAL BUSINESS ENVIRONMENT

teach managers about the global competitive landscape, when countries like China and

India are fundamentally changing the rules of the game?

1.2 Free trade and economic nationalism/

protectionism

1.2.1 International trade

The global economy is not a new concept, and international or global companies have

existed for many years. The British East India Company, founded in 1600, is popularly

cited as the world’s fi rst international and global company though, hundreds of years earlier,

China was trading extensively with Europe by means of the ‘silk route’. Today, however, it

is no longer the case that international business means Western multinational companies

selling to or operating in world markets.

1.2.2 Liberalisation – free trade

Free trade: The movement of goods, services, labour and capital without tariffs,

quotas, subsides, taxation, or other barriers likely to distort the exchange.

The concept of Free trade has been debated extensively for many years with advocates

arguing that:

●

Free trade will make society richer, since the free movement of goods and services allows

for local specialisation.

●

Free trade will mean that nations can develop their resources to gain a competitive

advantage.

●

The fact that countries trade and communicate should reduce confl ict.

●

Free trade will lead to dramatic increases in the well being of one population, as the

exposure to the higher standards of another nation are more rapidly adopted.

●

The quality of the goods will be better in absolute terms, and this will lead to a better

quality of life generally.

●

Since the trade is a voluntary exchange it will necessarily be for the mutual benefi t of

both parties.

●

Allowing entrepreneurship and investment a free rein will lead to more rapid growth in

the economy.

●

The fact that trade can be reciprocal will encourage both sides to export.

●

Free trade is considered to be a fundamental right.

●

Free trade is often encouraged for political reasons – the US actively supported the

free trade in fl owers with Colombia so that farmers would grow carnations rather than

cocaine.

However, there are criticism of free trade:

●

Countries get locked in to supplying a particular set of products or services, and do not

develop alternative products. The Middle East dependence on oil exports was always

given as an example of this.

5

ENTERPRISE OPERATIONS

THE GLOBAL BUSINESS ENVIRONMENT

●

Less developed countries are disadvantaged in some product groups, notably those

with high technology content. The case of life saving pharmaceuticals is often quoted

where developed countries charge premium prices and fi ercely protect their intellectual

property.

●

Free trade undermines national culture. France has resisted the import of American cul-

ture through cinema and radio for a number of years and has media legislation in place

restricting the amount of broadcasts in languages other than French.

●

The infl uence of multinationals is often so strong in the country in which they operate

that it can be used to corrupt the political system.

●

The impact of outsourcing abroad, known as offshoring, is damaging both to the nation

from which the jobs are exported but also to the host country. Whilst the labour rates

are lower in the host country quite often the safety standards are as well. There may well

be a lack of basic human rights and other considerations which the people of the coun-

try outsourcing the work take for granted.

●

Free trade reduces national security by reducing border controls.

●

International free trade is ineffi cient, as consumer expectations are increased. Many peo-

ple in the developed world are no longer satisfi ed with seasonal produce and the cost of

shipping out of season fruit and vegetables around the world, usually by air, is high to

the consumer and damaging to the environment.

●

Protectionism may actually be good for young fi rms in emerging industries.

There are a number of alternatives to Free Trade policies. In some instances two countries

will attempt a policy of ‘balanced trade’, whereby they will try to maintain a fairly even rela-

tionship between their respective imports and exports so that neither country runs a large

trade defi cit. Another approach is to actually try to protect the local market by restricting

imports. This is known as economic nationalism or, more commonly, protectionism.

1.2.3 Economic nationalism

Protectionism: Where one country, or trade bloc, attempts to restrict trade

with another, to protect their producers from competition.

Traditionally, protectionism meant the imposition of taxation on imported goods, much

the same as a purchase tax. This would have the effect of making those goods more expen-

sive than locally produced goods, and would discourage their purchase. Where the goods

continued to be purchased the tax would be a source of revenue for the government that

could, in theory, be invested to make local production more effective. This approach was

common in the United States immediately after World War II, allowing the country to

maintain a low rate of income tax and encourage high growth in the economy, often using

capital borrowed from the countries from which they restricted imports.

There are a number of ways in which markets can be protected without the use of

tariffs:

●

Quota systems. A quota will restrict the imports to a particular level, and locally pro-

duced goods will become more expensive. The government will receive reduced tariff

income.

STUDY MATERIAL E1

6

THE GLOBAL BUSINESS ENVIRONMENT

●

Buy national campaigns. Sometimes a country will encourage its citizens to buy locally

produced goods – on other occasions it will enforce this with regulations. A government

may say that a particular product must have a certain percentage of locally produced

components or labour (as is often the case in car manufacture) or will require fi rms to

report quarterly the sources of any purchases over a certain value, and tax them if the

proportion of foreign goods is too high.

●

Customs valuations. This approach is not so common now but in the past some govern-

ments have insisted that customs duty be paid on invoice cost plus a percentage, effec-

tively increasing the cost to the importer.

●

Technical barriers. Some countries insist on over stringent standards of quality, health

and safety, packaging or size to restrict what may be imported. At one point in time,

as environmental legislation, Germany insisted that foreign fi rms importing goods into

Germany were responsible for collecting and removing packaging from the country. This

increased transport costs to such a level as to make many such goods no longer economi-

cally viable. Similarly North America introduced standards for cars requiring the bumpers

to be a particular height which was impractical for imported sub-compact cars made by

Toyota and Honda.

●

Subsidies for local manufacturers. This is particularly prevalent for agricultural products

in North America and also in the EU, where the Common Agricultural Policy protects

small farmers in the European countries. There has been an ongoing battle between

Airbus and Boeing whose respective governments have supported the development of

each new airliner with which the companies have sought to dominate the market.

Most developed nations have agreed to abolish protectionism, and policies that favour free

trade are encouraged through organisations such as the World Trade Organisation. (http://

www.wto.org)

1.3 Comparative and competitive advantage

1.3.1 Comparative advantage

Adam Smith realised that international trade would allow each country to specialise in

what they could do best and without import tariffs and quotas, the nations of the world

could all benefi t by producing and selling the goods and services at which they had ‘abso-

lute advantage’. With all nations trading freely together, without the intervention of

governments, the ‘invisible hand’ of the market mechanism would ensure that everyone

gained. The problem was that this might create problems. If an established industry within

one country loses its absolute advantage, it is often not easy to switch from one activity to

another, especially if large investments have been made to establish the industry in the fi rst

place. In addition, skilled workers cannot or do not want to change to another activity.

Developments were made to the theory that Adam Smith had formulated and these

were introduced by David Ricardo, who focussed on the availability and skills of the

labour force. Two Swedish economists, Hecksher and Ohlin, elaborated on Ricardo’s ver-

sion by also bringing the availability of the other factors of production, land and capital,

into the analysis. Both theories suggested that even if a country could produce a prod-

uct, it could be better to import the goods from abroad. This would mean that their local

industry could focus all their attention on the production of the goods at which they had

the greatest advantages. This meant that if they could produce oil but the same quality

7

ENTERPRISE OPERATIONS

THE GLOBAL BUSINESS ENVIRONMENT

imported from Saudi Arabia was cheaper, then they should import their requirements and

focus their attention on the production of motor vehicles or electronic goods. This was the

theory of Comparative Advantage.

Factors such as climate, which would allow certain crops to be cultivated or natural

resources, such oil reserves did prescribe what products could be produced. But the the-

ory of comparative advantage provided an explanation of why tea, oil and products that

needed high levels of technological knowledge and skill were produced in specifi c coun-

tries. However, it did not explain the patterns by which a country such as Germany would

export chemicals, motor vehicles and machinery.

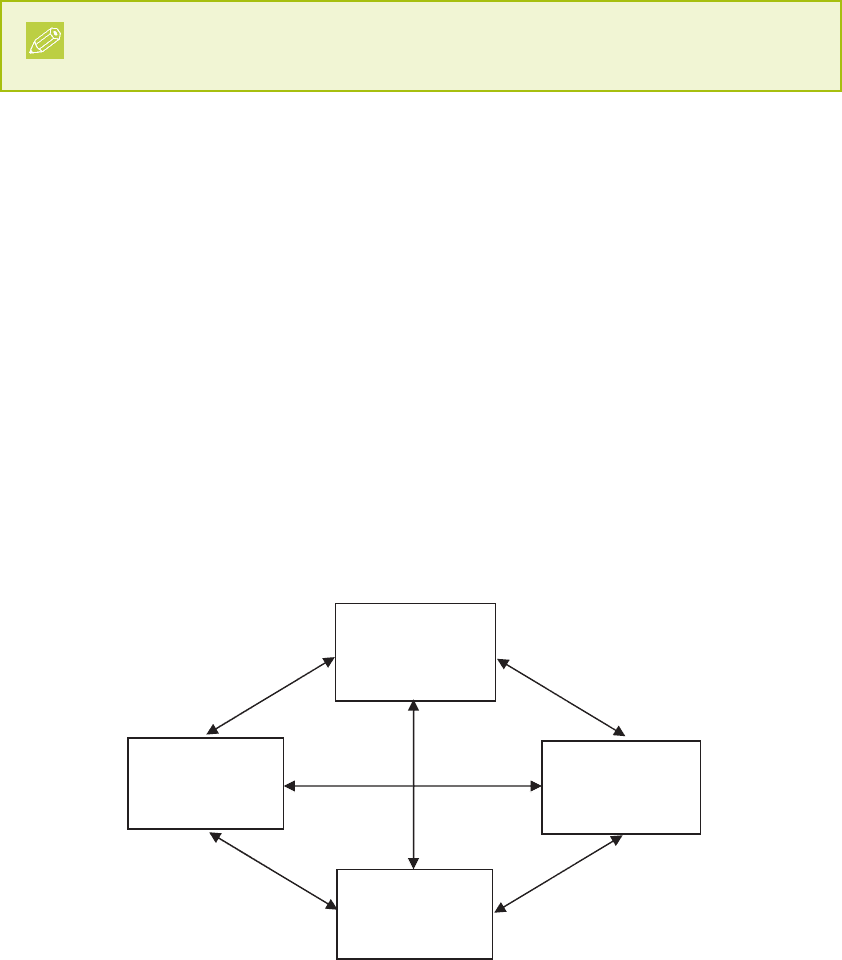

1.3.2 Competitive advantage – Porter’s Diamond

Porter’s Diamond is very examinable, and is also covered by later papers in the

CIMA qualifi cation. Make sure you understand it.

The internationalisation and globalisation of markets raises issues concerning the national

sources of competitive advantages that can be substantial and diffi cult to imitate. Porter, in

his book The Competitive Advantage of Nations (1992), explored why some nations tend to

produces fi rms with sustained competitive advantage in some industry more than others.

He set out to provide answers to:

1. Why do certain nations host so many successful international fi rms?

2. How do these fi rms sustain superior performance in a global market?

3. What are the implications of this for government policy and competitive strategy?

Porter concludes that entire nations do not have particular competitive advantages. Rather,

he argues, it is specifi c industries or fi rms within them that seem able to use their national

backgrounds to lever world-class competitive advantages.

Porter’s answer is that countries produce successful fi rms mainly because of the follow-

ing four reasons, as illustrated in Figure 1.1.

Firm strategy,

structure

and rivalry

Demand

conditions

Factor conditions

Related and

supporting

industries

Figure 1.1 Porter’s Diamond

STUDY MATERIAL E1

8

THE GLOBAL BUSINESS ENVIRONMENT

Demand conditions

The demand conditions in the home market are important for three reasons:

1. I

f the demand is substantial it enables the fi rm to obtain the economies of scale and

experience effects it will need to compete globally.

2. The experience the fi rm gets from supplying domestic consumers will give it an infor-

mation advantage in global markets, provided that:

(a) its customers are varied enough to permit segmentation into groups similar to those

found in the global market as a whole;

(b) its customers are critical and demanding enough to force the fi rm to produce at

world-class levels of quality in its chosen products;

(c) its customers are innovative in their purchasing behaviour and hence encourage the

fi rm to develop new and sophisticated products.

3. If the maturity stage of the plc is reached quickly (say, due to rapid adoption), this will

give the fi rm the incentive to enter export markets before others do. (Product life cycles

(plc) are covered in 4.9.2. later)

Related and supporting industries

The internationally competitive fi

rm must have, initially at least, enjoyed the support of

world-class producers of components and related products. Moreover success in a related

industry may be due to expertise accumulated elsewhere (e.g. the development of the Swiss

precision engineering tools industry owes much to the requirements and growth of the

country’s watch industry).

Factor conditions

These are the basic factor endowments referred to in economic theory as the source of so-

called comparativ

e advantage. Factors may be of two sorts:

1. Basic factors such as raw materials, semi-skilled or unskilled labour and initial capital

availability. These are largely ‘natural’ and not created as a matter of policy or strategy.

2. Advanced factors such as infrastructure (particularly digital telecommunications), levels

of training and skill, R&D experience, etc.

Porter argues that only the advanced factors are the roots of sustainable competitive suc-

cess. Developing these becomes a matter for government policy.

Firm structure, strategy and rivalry

National cultures and competitive conditions do create distinctive business focusses. These

can be infl uenced

b

y:

●

ownership structure;

●

the attitudes and investment horizons of capital markets;

●

the extent of competitive rivalry;

●

the openness of the market to outside competition.

Other events

Porter points out that countries can produce world-class fi rms due to two further factors:

1. The role of government. Subsidies, legislation and education can impact on the other

four elements of the diamond to the benefi t of the industrial base of the country.

9

ENTERPRISE OPERATIONS

THE GLOBAL BUSINESS ENVIRONMENT

2. The role of chance events. Wars, civil unrest, chance factor discoveries, etc. can also

change the four elements of the diamond unpredictably.

National competitive advantage

Successful fi rms fr

om a par

ticular country tend to have linkages between them; a phenom-

enon that Porter calls clustering.

Clustering allows for the development of competitive advantage for several reasons:

●

transfer of expertise, for example, through staff movement and contracts;

●

concentration of advanced factors (e.g. telecommunications, training, workforce);

●

better supplier/customer relations within the value chain (i.e. vertical integration).

Clustering may take place in two ways:

1. common geographical location (e.g. Silicon Valley, City of London);

2. expertise in key industry (e.g. Sweden in timber, wood pulp, wood-handling machinery,

particleboard furniture).

1.4 Outsourcing and offshoring

1.4.1 The growth of outsourcing

This section looks at key ‘boundary of the fi rm’ decisions. These are the decisions a fi rm

makes over whether to make components (or perform activities) itself, or whether to sub-

contract or outsource such production (or processes) to a supplier.

A competence: An activity or process through which an organisation deploys or

utilises its resources. It is something the organisation does, rather than some-

thing it has.

Strategic competences can be classifi ed as follows:

●

Threshold competence is the level of competence necessary for an organisation to com-

pete and survive in a given industry and market. For example, an online bookseller must

have a logistics system that allows books to be delivered as promised, to the customers

who have bought them.

●

A core competence is something the organisation does that underpins a source of com-

petitive advantage. For example, if an online bookseller is able to deliver books a day or

two earlier than its rivals, this represents a core competence.

Cox has developed a different way of looking at competences in terms of strategic supply

chain management. He suggests that competences come in three types, as follows:

1. Core competences. These are areas where the organisation should never consider out-

sourcing, as they are those competences that give a competitive advantage. In this case,

the decision should always be to make or do.

2. Complementary competences. In this case, the fi rm should outsource, but only to

trusted key suppliers who have the skills to supply as required. The fi rm would also

enter into a strategic relationship with the supplier.

STUDY MATERIAL E1

10

THE GLOBAL BUSINESS ENVIRONMENT

3. Residual competencies. In these areas, the organisation should outsource by means of

an ‘arms length’ relationship – a simple ‘buy’ decision.

Thus, when making strategic ‘make/do or buy’ decisions, the organisation should deter-

mine what type of competence is being considered.

Quinn and Hilmer put forward three tests for whether any non-core activity should be

outsourced:

1. What is the potential for gaining competitive advantage from this activity, tak-

ing account of transaction costs? The lower the potential, the more sensible it is to

outsource.

2. What is the potential vulnerability to market failure that could arise if the activity was

outsourced? Once again, the lower the risk, the more sensible it is to outsource.

3. What can be done to reduce these risks by structuring arrangements with suppliers in

such a way as to protect ourselves? In this case, the more we can protect ourselves, the

more sensible it is to outsource.

1.4.2 Advantages of outsourcing

The main advantages of outsourcing are thought to include the following:

●

That it allows more accurate prediction of costs and, hopefully, improves budgetary

control.

●

That, due to the specialist nature of the external provider, the services received will be of

a higher standard.

●

The supplier should be able to provide a cheaper service, due to economies of scale from

specialisation.

●

The organisation will be relieved of the burden of managing specialist staff in an area

that the organisation does not really understand.

●

It supports the concept of the ‘fl exible fi rm’.

1.4.3 Drawbacks of outsourcing

The main disadvantages of outsourcing are:

●

The diffi culty of agreeing and managing a ‘service level agreement’ (SLA).

●

The rigidity of the SLA and the contract with the supplier might prevent the organisa-

tion from exploiting new developments.

●

It is almost impossible to change outsourcing supplier or to revert to in-house provision.

1.4.4 Offshoring

Offshoring: Transferring some part of the organisation’s activities to another

country, in order (generally) to exploit differentials in wage rates.

Strictly speaking, the term includes both having a subsidiary or department in the other

country, and contracting out (or outsourcing) the supply of services to a foreign fi rm. These

two approaches are often differentiated by referring to the latter as ‘offshore outsourcing’.

11

ENTERPRISE OPERATIONS

THE GLOBAL BUSINESS ENVIRONMENT

Whether offshoring is done ‘in-house’ or by means of an outsourcing agreement, the

motivation is usually to exploit lower labour costs in the other country. Although such dif-

ferentials in wage rates can be signifi cant (often in the order of one tenth the level of the

‘home’ country) there are a number of issues, other than cost, that should be considered.

Managing operations (or outsourcing agreements) across national borders can lead signifi -

cant to issues in areas such as:

●

Language barriers

●

Time differences

●

Exchange rate effects

●

Cultural differences (see later in this chapter)

●

Real (or perceived) service levels

Despite all these concerns, the signifi cant economic benefi ts of offshoring mean its growth

continues. A recent estimate of the Indian offshoring market, for example, estimated total

annual revenues at US$35 billion, two-thirds of which was from the provision of IT-

related services. This fi gure represented an increase of $10 billion over the previous year.

1.5 Emerging market multinationals

1.5.1 Globalisation

Globalisation: The growing economic interdependence of countries worldwide

through increased volume and variety of cross border trade in goods and serv-

ice, freer international capital fl ows, and more rapid and widespread diffusion of

technology. (Source: IMF)

Globalisation: The freedom and ability of individuals and fi rms to initiate vol-

untary economic transactions with residents of other countries. (Source: World

Bank)

We can see from these defi nitions that there are signifi cant elements of political, cultural,

economic and technological factors in globalisation. In fact, globalisation has been consid-

ered to consist of fi ve monopolies based on; technology, fi nance, natural resources, mass

media and weapons of mass destruction.

The features of globalisation are:

●

the ability of multinational organisations to exploit arbitrage opportunities across differ-

ent tax jurisdictions,

●

the lowering of transaction costs by developments in communications and transport,

●

the rise of the fi nancial service industries,

●

the reduction of the importance of manufacturing industry,

●

the rise of the newly industrialised nations by the exploitation of cheaper labour, and

●

the increasing importance of global economic policy over national sovereignty.