Carranza E. Geochemical anomaly and mineral prospectivity mapping in GIS

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

140 Chapter 5

Because of the apparent similarity between the spatial distributions of anomalous

PC2 and negated PC3 scores, it is appealing to integrate such variables into one variable

representing a multi-element As-Ni-Cu association reflecting the presence of epithermal

Au deposits. A simple multiplication can be applied to integrate the PC2 and negated

PC3 scores, although this creates false anomalies from PC2 and negated PC3 scores that

are both negative. This problem is overcome by first re-scaling the PC2 and negated PC3

scores linearly to the range [0,1] and thereafter performing multiplication on the re-

scaled variables. The resulting ‘integrated As-Ni-Cu’ scores are then portrayed as a

discrete surface, using the sample catchment basins, for the application of the

concentration-area fractal method to separate background and anomaly.

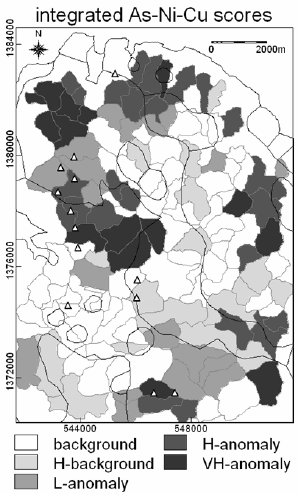

The spatial distributions of integrated As-Ni-Cu scores (Fig. 5-12) show adjoining

high and very high anomalies, which coincide or are proximal to most epithermal Au

deposit occurrences. Most of the high anomalies of PC2 scores in the southeastern

quadrant of the area (Fig. 5-11A) have been downgraded in importance (i.e., they now

map as low anomalies as shown in Fig. 5-12), but many of the low and high anomalies

Fig. 5-12. Spatial distributions of integrated As-Ni-Cu scores obtained as products of PC2 and

negated PC3 scores representing anomalous multi-element associations derived via principal

components analysis (Table 5-IX; Fig. 5-11) of rank-transformed dilution-corrected uni-element

residuals in stream sediment samples, Aroroy district (Philippines). The background and

anomalous populations of integrated As-Ni-Cu scores were modeled via concentration-area fractal

analysis. L = low; H = high; VH = very high. Triangles represent locations of epithermal Au

deposit occurrences, whilst thin black lines represent lithologic contacts (see Fig. 3-9).

Catchment Basin Analysis of Stream Sediment Anomalies 141

of both PC2 and negated PC3 scores in the northwestern quadrant of the area (Fig. 5-

11B) have been upgraded in importance (i.e., they now map as high anomalies as shown

in Fig. 5-12). In addition, many of the low anomalies of negated PC3 scores in the

eastern parts of the area (Fig. 5-11B) have been enhanced. Combining the PC2 (Ni-Cu-

As) and negated PC3 (As) scores into integrated As-Ni-Cu scores has an overall positive

effect in this case study and is therefore defensible.

Screening of multi-element anomalies with fault/fracture density

The presence of stream sediment uni-element or multi-element anomalies does not

always mean presence of mineral deposits, so it is necessary to apply certain criteria for

ranking or prioritization of anomalies prior to any follow-up work. Criteria for ranking

or prioritization can be related to indicative geological features of the mineral deposit

type of interest or to factors that could influence localisation of stream sediment

anomalies.

In the study area, faults/fractures can influence localisation of stream sediment

anomalies because (a) such geological features are common loci of epithermal Au

deposits, whose element contents find their way into streams due to weathering and

erosion and (b) the presence of such geological features indicates enhanced structural

permeability of rocks in the subsurface, which facilitates upward migration of

groundwaters that have come in contact with and have leached substances from buried

deposits. These arguments suggest that the significance of multi-element stream

sediment anomalies in sample catchment basins can be screened or examined further by

using fault/fracture density as a factor (cf. Carranza and Hale, 1997).

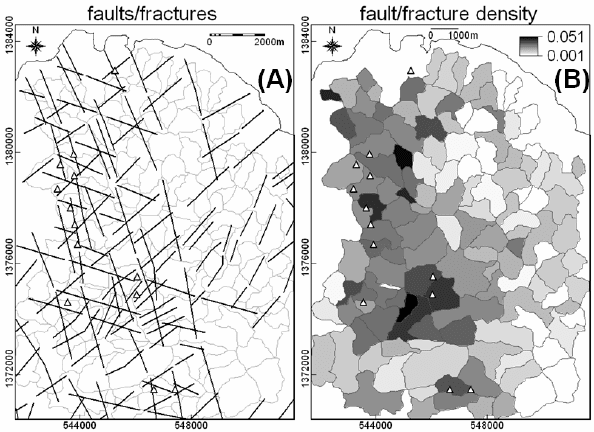

Fig. 5-13A shows a map of faults/fractures in the study area, indicating that the

epithermal Au deposits are localised mostly along certain north-northwest-trending

faults/fractures. A fault/fracture density map can be created by calculating, per sample

catchment basin, the ratio of number of pixels representing faults/fractures in a sample

catchment basin to number of pixels in that sample catchment basin. Most of the

epithermal Au deposit occurrences in the study area are situated in sample catchment

basins with moderate to high fault/fracture density (Fig. 5-13B). In order to further

screen the multi-element stream sediment anomalies (e.g., as shown in Fig. 5-12), the

product of integrated As-Ni-Cu scores and fault/fracture density can be obtained and

then subjected to classification via the concentration-area fractal method.

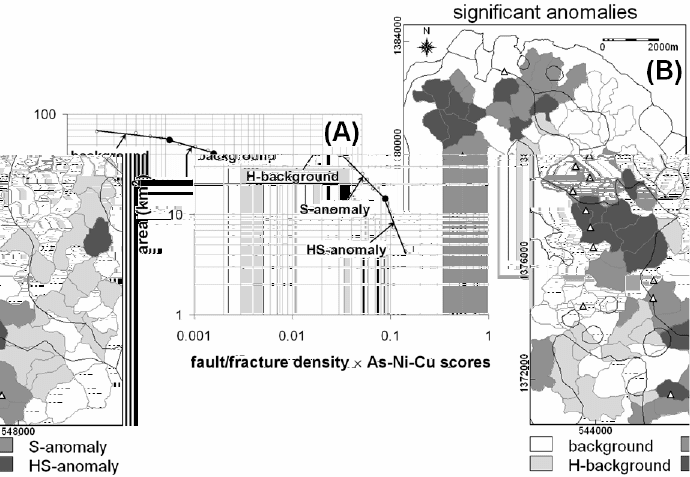

The results shown in Fig. 5-14 clearly indicate that, on the one hand, anomalies of

integrated As-Ni-Cu scores in the western half of the study area (see Fig. 5-12) are

mostly significant in terms of indicating localities that contain or are proximal to

epithermal Au deposit occurrences. The anomalous sample catchment basins in the

western half of the study area (Fig. 5-14) are aligned along the north-northwest trend of

the epithermal Au deposit occurrences. On the other hand, anomalies of integrated As-

Ni-Cu scores related to the Aroroy Diorite in the eastern half of the study area (see Fig.

5-12) are downgraded in importance (i.e., they now map mostly as background as shown

in Fig. 5-14) after using fault/fracture density in the analysis. This latter result suggests

that the Aroroy Diorite is possibly non-mineralised.

142 Chapter 5

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

There are various factors that influence variation in stream sediment background uni-

element concentrations. For example, it has been shown in some case studies that

drainage sinuosity (Seoane and De Barros Silva, 1999), which is a geogenic factor, and

selective logging (Fletcher and Muda, 1999), which is an anthropogenic factor, can

influence the variability of background uni-element concentrations in stream sediments.

Nevertheless, a universal factor of variation in stream sediment background uni-element

concentration is lithology. Estimation and removal of local background uni-element

concentrations in stream sediments due to lithology from measured stream sediment uni-

element concentrations is vital to the recognition of significant geochemical anomalies.

The results of the case study demonstrate that significant uni-element and multi-

element anomalies can be extracted from stream sediment geochemical data through a 5-

stage GIS-based methodology involving: (1) estimation of local background uni-element

concentrations due to lithology per sample catchment basin; (2) removal of estimated

local background uni-element concentrations due to lithology from measured uni-

element concentrations, which results in geochemical residuals; (3) dilution-correction of

geochemical residuals using a modified formula from the relation proposed by Hawkes

Fig. 5-13. (A) Map of faults/fractures in the Aroroy district (Philippines), compiled mostly from

unpublished literature and interpretations of shaded-relief images of DEM illuminated from

different directions (e.g., Fig. 4-11). (B) Fault/fracture density measured as the ratio of number o

f

p

ixels representing faults/fractures in a sample catchment basin to number of pixels per sample

catchment basin. Triangles represent locations of epithermal Au deposit occurrences.

Catchment Basin Analysis of Stream Sediment Anomalies 143

(1976); (4) modeling of uni-element and/or multi-element anomalies via application of

the concentration-area fractal method; (5) screening of significant anomalies by

integration of factors that favour mineral deposit occurrence, such as fault/fracture

density.

Consideration of the area of influence of every stream sediment sample location – its

catchment basin – is the key in stages (1) and (3). In stage (1), more stable estimates of

local background uni-element concentrations due to lithology can be obtained by using

areas of lithologic units per sample catchment divided by the total area of sample

catchment basins instead of using areal proportions of lithologic units per sample

catchment basin. In stage (3), dilution-correction of uni-element residuals is based on

area of sample catchment basins plus an assumption of a small unit area of exposed

anomalous sources (e.g., mineral deposits). Correction for downstream dilution using

either equation (5.8) or (5.9) (i.e., based on the assumption of a unit area for exposed

anomalous sources contributing to uni-element concentrations in stream sediments), is

Fig. 5-14. Results of synthesis and analysis of fault/fracture density and integrated As-Ni-Cu

scores, Aroroy district (Philippines). (A) Log-log plot of concentration-area fractal model o

f

products of fault/fracture density and integrated As-Ni-Cu scores, showing three thresholds (dots)

at breaks in slopes of straight lines representing populations of background, high (H) background,

significant (S) anomalies and highly significant (HS) anomalies. (B) Spatial distributions o

f

background and anomalous populations of products of fault/fracture density and integrated As-Ni-

Cu scores based on thresholds recognised in the concentration-area plot. Triangles in the map

represent locations of epithermal Au deposit occurrences, whilst thin black lines represent

lithologic contacts (see Fig. 3-9).

144 Chapter 5

appropriate for analysis of stream sediment geochemical data in regions where there are

some occurrences of mineral deposits of interest. In regions where there are no known

occurrences of mineral deposits of interest, it is prudent to calculate productivity (Moon,

1999) or ‘stream-order-corrected’ residuals (Carranza, 2004a). Note, nonetheless, that

correcting for downstream dilution by using either equation (5.8) or (5.9) neglects

contributions from overbank materials, assumes lack of interaction between sediment

and water and that erosion is uniform in each catchment basin. Certainly, the

downstream dilution-correction model based on the idealised relation proposed by

Hawkes (1976), which is adopted in the case study, does not apply universally.

However, the idealised formula proposed Hawkes (1976) shows reasonable agreement

between theory and prediction of known porphyry copper deposits in his study area. In

addition, considering that sizes of catchment basins differ and that sizes of anomalous

sources (if present) could differ from one catchment basin to another, dilution-correction

is warranted despite limitations of the model.

Prior to stage (4), if dilution-corrected residuals are derived from ‘homogeneous’

subsets of stream sediment geochemical data, then application of robust statistics for

exploratory data analysis is preferred for standardisation of dilution-corrected residuals

per data subset instead of the conventional application of classical statistics for

standardisation. In stage (4), the results of the case study further demonstrate usefulness

of fractal analysis (Cheng et al., 1994) of discrete geochemical surfaces (i.e., catchment

basins polygons) of uni-element residuals and derivative scores representing multi-

element data. In the past, recognition of anomalies from dilution-corrected residuals was

made by visual inspection of spatial distributions of percentile-based classes of such

variables (Bonham-Carter and Goodfellow, 1986; Bonham-Carter et al., 1987; Carranza

and Hale, 1997). Now, recognition of anomalies from dilution-corrected residuals can be

made objectively by application of the concentration-area fractal method. In stage (5),

the area of influence of individual sample catchment basins is further useful in screening

of anomalies, as demonstrated in the case study using fault/fracture density estimated as

the ratio of number of pixels representing faults/fractures in a sample catchment basin to

number of pixels in that sample catchment basin. In another GIS-based case study,

Seoane and De Barros Silva (1999) prioritised sediment sample catchment basins that

are anomalous for gold by using catchment basin drainage sinuosity, which is estimated

as the ratio of total length of streams within a sample catchment basin to the total

distance between the start and end points of the main stream and its tributaries in that

sample catchment basin. Finally, it is clear that GIS supplements catchment basin

analysis of stream sediment anomalies with tools for data manipulation, integration and

visualisation in discriminating and mapping of significant geochemical anomalies.

147

Chapter 6

ANALYSIS OF GEOLOGIC CONTROLS ON MINERAL OCCURRENCE

INTRODUCTION

Occurrences (or locations) of mineral deposits of the type sought are themselves

significant geochemical anomalies and are samples of a mineralised landscape. The

spatial distribution of such samples is invariably considered by many geoscientists,

especially mineral explorationists, to be non-random because of the knowledge that an

inter-play of certain geological processes has controlled their occurrence. It follows then

that such samples of a mineralised landscape are associated spatially, as well as

genetically, with certain geological features. It is for these reasons that mineral

prospectivity for the type of deposits sought is, in many cases, modeled by way of

probabilistic techniques. That is to say, the probability or likelihood that mineral deposits

of the type sought are contained or can be found in a part of the Earth’s crust is

considered greater than would be expected due to chance.

We recall from Chapter 1 that, in any scale of target generation, modeling of mineral

prospectivity usually starts with the definition of a conceptual model of mineral

prospectivity for mineral deposits of the type sought (Fig. 1-2). Analysis of the spatial

distribution of occurrences of mineral deposits of the type sought and analysis of their

spatial associations with certain geological features are useful in defining a conceptual

model of mineral prospectivity of the type sought in a study area. Analysis of the spatial

distribution of occurrences of mineral deposits of the type sought can provide insights

into which geological features have plausibly controlled their localisation at certain

locations. In addition, the analysis of spatial associations between occurrences of mineral

deposits of the type sought and certain geological features is instructive in defining and

weighting relative importance of certain geological features to be used as spatial

evidence in predictive modeling of mineral prospectivity.

This Chapter explains techniques for analysis of the spatial distribution of

occurrences of mineral deposits of the type sought and techniques for the analysis of

spatial associations between occurrences of mineral deposits of the type sought and

certain geological features. These techniques are demonstrated by using a map of

occurrences of epithermal Au deposits in the case study Aroroy district (Philippines)

(Fig. 3-9) in order to define a conceptual model of prospectivity for this type of mineral

deposit in that district. Models of multi-element anomalies, which are derived by

applications of the methods explained and demonstrated in Chapters 3 to 5, are examined

further here in terms of their spatial associations with the known occurrences of

Geochemical Anomaly and Mineral Prospectivity Mapping in GIS

by E.J.M. Carranza

Handbook of Exploration and Environmental Geochemistry, Vol. 11 (M. Hale, Editor)

© 2009 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved

.

148 Chapter 6

epithermal Au deposits in the case study area. Faults/fractures in the case study area

(Fig. 5-13) are also used as input data in the spatial association analysis in order to

define prospectivity recognition criteria representing structural controls on epithermal

Au mineralisation. However, let us proceed first with the analysis of the spatial

distribution of occurrences of the epithermal Au deposits in the case study area in order

to gain insights into their geologic controls.

SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION OF MINERAL DEPOSITS

In most case studies of mineral prospectivity mapping, the locations of known

mineral deposits of the type sought are depicted as points. Thus, a univariate point map

(of mineral deposits of the type sought) is used as input data in the analysis of the spatial

distribution of mineral deposits. Three methods to characterise the spatial distribution of

occurrences of mineral deposits of the type sought are explained and demonstrated here:

point pattern analysis, fractal analysis and Fry analysis.

Point pattern analysis

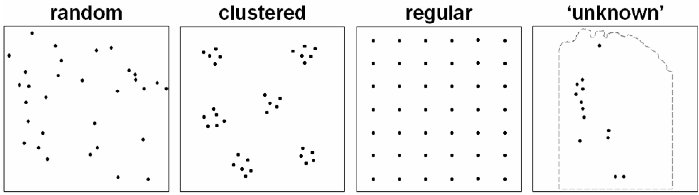

Point pattern analysis is a technique that is used to obtain information about the

arrangement of point data in space to be able to make an inference about the spatial

distribution of occurrences of certain geo-objects represented as points. There are three

basic types of point patterns (Diggle, 1983) (Fig. 6-1).

1.

A pattern of complete spatial randomness (CSR), in which points tend to lack

interaction with each other. This pattern suggests geo-objects resulting from

independent processes that occur by chance.

2.

A clustered pattern, in which points tend to form groups compared to points in

CSR. This pattern suggests geo-objects resulting from an inter-play of processes

that involve ‘concentration’ of groups of points to certain locations.

3.

A regular pattern, in which points tend to be farther apart compared to points in

CSR. This pattern suggests geo-objects resulting from an inter-play of processes

that involve ‘circulation’ of individual points to certain locations.

Fig. 6-1. Basic types of point patterns: random; clustered; regular. The ‘unknown’ point pattern

represents known occurrences of epithermal Au deposits in the Aroroy district (Philippines)

demarcated in light-grey dashed outline (see Fig. 3-9).

Analysis of Geologic Controls on Mineral Occurrence 149

A point pattern under consideration is thus compared to a point pattern of CSR. The null

hypothesis in point pattern analysis is, therefore, that the point pattern under examination

assumes CSR and that the geo-objects represented by the points are independent of each

other and each point is a result of a random (or Poisson) process. The plainest alternative

or ‘research’ hypothesis in point pattern analysis is that the point pattern under

investigation does not assume CSR and that the geo-objects represented by the points are

associated with each other because they were generated by common processes. Thus, if

occurrences of mineral deposits of the type sought are non-random, they may display a

clustered distribution or a more or less regular distribution. There are various techniques

by which the null hypothesis or the alternative hypothesis can be tested and they can be

grouped generally into two types of measures (Boots and Getis, 1988): (1) measures of

dispersion; and (2) measures of arrangement.

Measures of dispersion study the locations of points in a pattern with respect to the

study area. Measures of dispersion can be further subdivided into two classes: (a)

quadrat methods; and (b) distance methods. Quadrat methods make use of sampling

areas of a unit size and consistent shape (e.g., a square pixel), which can be either

scattered or contiguous, to measure and compare frequencies (or occurrences) of

observed points to expected frequencies of points in CSR. It is preferable to make use of

contiguous quadrats (e.g., a grid of square pixels) instead of scattered quadrats in the

analysis of the spatial distribution of occurrences of mineral deposits of the type sought.

That is because scattered quadrats are positioned at randomly selected locations,

producing a bias toward CSR. Choosing a quadrat size, however, is a difficult issue in

using contiguous quadrats: large quadrats tend to result in more or less equal

frequencies, which generate bias toward a regular or a clustered pattern; small quadrats

can break up clusters of points, resulting in a bias toward CSR. The best option is to

apply distance methods, which compare measured distances between individual points

under study with expected distances between points in CSR.

In a GIS, distance between two points is determined, based on the Pythagorean

theorem, as the square root of the sum of the squared difference between their easting (or

x) coordinates and the squared difference between their northing (or y) coordinates. In a

set of n points, measured distances from one point to each of the other points are referred

to as 1

st

-, 2

nd

-, 3

rd

- or (n-1)

th

-order neighbour distances; the 1

st

-order neighbour distance

being the nearest neighbour distance. If, on the one hand, the mean of measured n

th

-order

neighbour distances is smaller than the mean of expected n

th

-order neighbour distances

in CSR, then the set of points under examination assumes a clustered pattern. If, on the

other hand, the mean of measured n

th

-order neighbour distances is larger than the mean

of expected n

th

-order neighbour distances in CSR, then the set of points under

examination assumes a regular pattern. The significance of the difference between the

mean of measured n

th

-order neighbour distances and the mean of expected n

th

-order

neighbour distances in CSR may be determined statistically based on the normal

distribution; for details, readers are referred to Boots and Getis (1988).

The occurrences of epithermal Au deposits in the Aroroy district (Philippines),

according to the results of analysis of up to the 6

th

-order neighbour distances (Table 6-I),

150 Chapter 6

assume a regular distribution. Boots and Getis (1988) aver that the choice of how many

orders of neighbour distances to examine depends on the point pattern being studied.

Here, the choice of examining up to the 6

th

-order neighbour distances is arbitrary, but is

based on the assumption that unknown (or undiscovered) occurrences of mineral

deposits of the type sought are located close to the known occurrences. Note that the

mean of the measured 6

th

-order neighbour distances (about 4 km) is not an unrealistic

search radius from a known mineral deposit occurrence within which to explore for

undiscovered occurrences of the same type of mineral deposit. Determining the

statistical significance of the results is also considered here to be inappropriate because

the boundary of the study area is arbitrary (i.e., geologically non-real) and occurrences of

epithermal Au deposits outside the study area are thus excluded from the analysis.

Nevertheless, the results suggest that individual occurrences of epithermal Au deposits in

the study area were formed by an inter-play of geological features that ‘circulated’

mineralising hydrothermal fluids into certain localities. This generalisation is discussed

later in the synthesis of results from this analysis and the results of fractal and Fry

analyses that follow below.

In contrast with measures of dispersion, measures of arrangement study the locations

of points in a pattern with respect to each other. Measures of arrangement are useful

when the actual boundary of a study area is unknown or difficult to define or if it is not

necessary to impose an arbitrary boundary. In measures of arrangement, the observed

number of reflexive (or reciprocal) nearest neighbour (RNN) points is compared with the

expected number of RNNs in a situation of CSR. The CSR is simulated for the same area

and the same number of points. Two points are considered 1

st

-order RNN if they are

each other’s nearest neighbour in a neighbourhood of points, whereas 2

nd

-order RNNs

are points that are each other’s 2

nd

-nearest neighbours in a neighbourhood of points, and

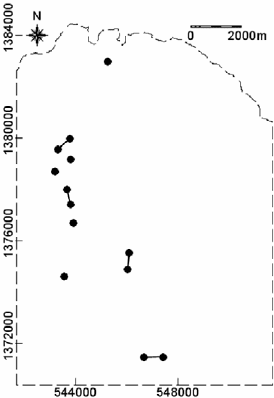

so on (Boots and Getis, 1988). In the study area, there are eight 1

st

-order RNNs (Fig. 6-

2). RNNs are always pairs of points, so that the observed number of RNNs is always an

even number. The expected number of j

th

-order RNNs is estimated according to the

probability that a point in CSR is the j

th

-nearest neighbour of its own j

th

-nearest

neighbour (see Cox (1981) for details). If the observed number of j

th

-order RNNs is

TABLE 6-I

Means of different orders of neighbour distances in the point pattern of occurrences of epithermal

Au deposits in Aroroy district (Philippines).

Order of neighbour distances

Mean of measured

distances (m)

Mean of expected

distances (m) in CSR

1

st

992.2 966.6

2

nd

1880.3 1449.9

3

rd

2249.9 1812.3

4

th

2660.9 2114.3

5

th

3222.0 2378.8

6

th

3765.6 2616.5

Analysis of Geologic Controls on Mineral Occurrence 151

higher than the expected number of j

th

-order RNNs in CSR, then the points under

examination assume a clustered pattern. If the observed number of j

th

is lower than the

expected number of j

th

-order RNNs in CSR expectations, then the points under

examination assume a regular pattern.

In a GIS, RNNs are determined automatically by software because they can be

computationally complex. The occurrences of epithermal Au deposits in the Aroroy

district (Philippines), according to the results of analysis of up to the 6

th

-order RNNs

(Table 6-II), tend to assume a regular distribution. The reason for examining up to the

6

th

-RNNs is simply for consistency with the analysis of dispersion discussed earlier.

Table 6-II shows that the observed numbers of j

th

-order RNNs are mostly slightly lower

than the expected numbers of j

th

-order RNNs. Unfortunately, according to Boots and

Getis (1988), there are no statistical tests available to examine the significance of the

difference between the observed and expected numbers of j

th

-order RNNs.

Tables 6-I and 6-II show that some discrepancy can occur between the results of

measures of arrangement and the results of measures of dispersion. Analysis of

dispersion by distance methods is more advantageous than analysis of arrangement

because the statistical theory for analysis of dispersion in terms of distances is better

developed than the statistical theory behind analysis of arrangement, so the former is less

subjective than the latter. That is to say, analysis of dispersion is parametric whilst

analysis of arrangement is non-parametric. The main advantage of analysis of

arrangement over analysis of dispersion by distance methods is that the former is free of

so-called edge-effects, because locations of points are studied with respect to each other

Fig. 6-2. 1

st

-order reflexive nearest neighbours (dots connected by a solid line) in the pattern o

f

p

oints (dots) representing occurrences of epithermal Au deposits in the Aroroy district

(Philippines) demarcated in light-grey dashed outline.