Campbell P. Power and Politics in Old Regime France, 1720-1745

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

POWER AND POLITICS IN OLD REGIME FRANCE

218

they had done, to avoid putting the aforementioned in a compromising

position and thus let them stand out, and become liable to some punishment;

thus it was that all the other consulting lawyers, who were not intending to

abandon work, did so out of sympathy for the others. All the young lawyers

are of M.Duhamel’s opinion, because they have nothing to lose, or rather no

employment, and because with the ardour of youth they like a fight and hope

to attract attention to themselves.

74

This is a splendid example of loyalty to the corporation outweighing other

loyalties.

75

The thesis of an exploitation of corporate solidarity and youthful hot-

headedness by a small group is strengthened when it is recalled that the same group

of barristers was responsible for all of the protests by their order in support of either

Jansenists or the parlement. We have seen how the protest of 1727 against the

Council of Embrun was penned by Aubry, ‘excellente plume’, as was the

denunciation of the declaration of 24 March 1730.

76

On 14 April 1730 there was an

attempt at a strike organised by Duhamel.

77

Maraimberg, ‘a great Jansenist’ was

behind a memoir of the forty lawyers supporting the parlement’s case that in

appeals comme d’abus the ecclesiastic would have his sentence imposed by the clerical

court suspended until the affair had been judged.

78

Six of the eight named above

signed the consultation against the Pastoral Instruction of bishop Languet condemning

the miracles in 1734.

79

Finally, it is interesting to note that this group of Jansenist

lawyers was composed of some of the most distinguished in the profession who

could earn 10,000 livres or more a year from cases and could own large hôtels.

Their collusion extended to a professional co-operation which reinforced their

power over their colleagues: ‘their cabal even went as far as sending each other

business, consulations, arbitrages, and depriving others of work’.

80

For all their efforts, as we shall see in the following chapters, the undivided stand

of the ministry and good political management combined to defeat them in the

1730s. It was a to be different story during the 1750s, when the abandonment of

Fleury’s policy of ecclesiastical patronage led to an increase in the number of cases

of refusal of the sacraments. Divisions within the ministry and the leadership of the

parlement gave the parti the opportunity to raise the issues with much greater

success.

In spite of, or rather because of, the lack of immediate success, the Jansenist

ecclesiology also affected the development of political thought in France. Although

the subject is at present under-investigated, theology and political theory were still

closely related. Keohane has stressed the debt of the Enlightenment to

Augustianism and Labrousse has insisted on the importance of Calvinism to Pierre

Bayle.

81

Historians are beginning to recognise that during the course of their

struggle, the parti janséniste made an important contribution to the political debates in

eighteenth-century France. Fully to understand this development it is necessary to

abandon the idea put forward by Lucien Goldmann that Jansenism was the

recourse of a class frustrated in its desire to express opposition to the absolutist

regime.

82

Even in the 1720s and early 1730s robe Jansenists believed in the doctrine

THE PARTI FANSENISTE IN THE 1720s AND 1730s

219

because it offered a way to salvation, and so their prime motivation was doctrinal

issues, not political. Once this more straightforward explanation is accepted, it can

be maintained that the Jansenists contributed to political theory in order to save

their sect from persecution. The defeat of the Jansenist-inspired parlement in the

1730s led the Jansenists to search for better arguments to defend themselves in their

quarrel against royal policy. From the time of Unigenitus until the 1750s, but

especially from the 1730s, some barristers began to revive older ideas on the origins

and nature of royal power in order to justify themselves more effectively. The most

famous of these, Le Paige, produced a propagandist history of the parlement in

1753 which argued that it had a constitutional role.

83

These ideas, whose origins can

be found at least as early as conciliarism and the religious wars of the sixteenth

century, made a substantial contribution to the eighteenth-century debate when

presented in a new context.

84

With the help of these theories and prompted by the

alliance between monarchy and episcopate, they began to regard the monarchical

authority which was imposing Unigenitus as despotic, and free registration of the

laws by the parlement as an essential check. These ideas were cross-fertilised with

the currents of constitutional thought derived from the new fascination with

England and the older classical tradition in which all educated men were steeped.

85

The development of these ideas can be traced from the time of the Regency

onwards. In 1719 Guillaume de Lamoignon, the procureur général had a Jansenist

libelle condemned by the Paris parlement in these terms in 1719:

[The author] is not afraid to render the people depository of the faith,

conjointly with their bishops; the only prerogative he grants the bishops is to

have them march in equal step with the curés of their diocese; thus according

to him it is not the flock which must obey the shepherd, it is the shepherd

who must entirely conform to the will of his flock. In this idea is to be found

the origin of his conception of sovereign authority which he attributes to the

Estates General of the Kingdom when they are assembled.

86

Lamoignon’s speculations on the pedigree of these ideas may not be quite right, but

it is clear that the scene was set for a transferral to the secular sphere of some

important ideas developed during the course of spiritual conflicts.

The full implications of the Jansenist revival and secularisation of earlier theory

would become apparent in the 1750s. The seeds of this are plainly present in the

1730s. The ‘Memoir of the Forty Lawyers’ of 1730 departed from the usual

language of politics in several important respects. It was studied closely and

commented upon by Chancellor Daguesseau. Where it said ‘according to the

Constitution of the Kingdom, the parlements are the Senate of the Nation, to render

in the name of the King who is its leader’, he remarked that the tradition in royal

ordinances expressly denied this ‘constitution’, that the senate was therefore not a

senate: ‘the King is therefore reduced to the rank of leader of the nation and France

becomes the Republic of Poland or of England’. Against the phrase ‘the parlement

is the depository of public authority’, he asked, ‘why not royal authority—the

POWER AND POLITICS IN OLD REGIME FRANCE

220

Parlement has never spoken thus’. He seizes on an assertion that gave the clue to the

barristers’ aims of altering ecclesiastical law, that ‘the parlements have the

characteristic of representing public authority’ and can reform ‘acts of both lay and

ecclesiastic jurisdiction’. ‘The Nation’s Tribunal’, they proclaim, and he observes,

‘Never the King’s’. The princes of the blood, the magistrates and the peers were all

held to be ‘the senators, the patrices and the assessors of the throne in the

administration of justice’—‘here we are again in Poland where the king is only the

head of the Republic!’ retorts the Chancellor. He regards the idea that a law is

formed by the wish of the nation, ‘in the assembly of Estates’ as frankly ‘seditious’.

87

A year later two publications in particular displayed a radical edge. The

Judiciumfrancorum and the Projet de remontrances. The former was a modified version of

a parlementary pamphlet of 1652. Beginning with a sentence that Montesquieu was

later to appropriate, the pamphlet argued:

When it is a question of something in which the people has an interest, it

cannot be decided in the council of state. The king can only contract with his

people in the Parlement, which, being as old as the crown itself and born with

the state, is the representation of the whole monarchy. The king’s council,

which is a kind of jurisdiction established to the prejudice of the most

fundamental laws of the kingdom, has no public character, and when it

annuls or modifies the arrêts of the Parlement it commits a clear usurpation.

88

The second publication, by the Oratorian Father Boyer, constructs in some measure

a Figurist ‘history of the state’, whose true defenders are beleaguered by enemies of

the throne’s best interests.

89

The idea that there was a need for a depository of the laws in the state was not

new to parlementary corporate theory, for it was expressed in La Roche Flavin’s

Thirteen Books on the Parlements in 1613, but it was paralleled and reinforced in the

1730s by the Figurist ecclesiology. As Maire has revealed, Figurism believed that in

the corrupted world, religious truth was a sacred trust safeguarded by a small band

of the often persecuted faithful. The Jansenists were thus the dépôt de la vérité, as the

parlements became in their writings the dépôt des lois.

90

It is more than likely that

Montesquieu, who knew the abbé Pucelle, and must have followed the Jansenist

controversy with interest (since he wrote of it in the Persian Letters), was influenced by

this conjunction of ideas. His arguments that It is not enough to have intermediate

ranks in a monarchy; there must also be a depository of the laws’, and the

subsequent statement that despotic states have neither fundamental laws nor a

depository of laws, seem to reflect the tenor of Jansenist publications in the 1730s.

91

In the 1750s the quarrel over the Bull Unigenitus gave rise to disputes that led to

the veil being torn from the mysteries of state. The language of despotism, the

sovereignty of the nation, and fundamental laws became current. The disputes to

which the Jansenists and parlementaire activities gave rise appear to have brought

about a change in attitude to the monarchy itself. The political debate took place

upon ground that was usually skilfully avoided by all parties to the dispute, namely

THE PARTI FANSENISTE IN THE 1720s AND 1730s

221

the nature of royal authority (and not, since there was not one, the constitution). In

the absence of an agreed constitution, there were dangerous implications in pushing

theoretical positions to their limits. The vehemence of the Jansenists ensured that

arguments were pushed to their logical conclusions, and the very basis of the

monarchy subjected to the closest scrutiny. In this situation it was hard for the

crown to retain respect for its role, especially since its own propagandists were less

effective and its ministers more interested in factional conflict than defences of the

theocratic absolute monarchy. From being above discussion in the seventeenth

century, the monarchy had gone on to provoke serious criticism of the way it

operated under Louis XIV, and now was exposed to fundamental challenge to its

principles of operation.

Given the limited effectiveness of censorship at the time, perhaps no ministry

could have prevented these consequences, but the cardinal de Fleury certainly

prevented the effective conjunction of Jansenism and the Paris parlement while he

lived. The cardinal de Bernis, who had considerable experience of managing the

parlements, assessed Fleury’s control over the parti janséniste during his ministry in

the following manner.

The ministry of the cardinal de Fleury had almost destroyed Jansenism in

France. He was wise. Violent means were not to his taste, and although on

many occasions he did not always uphold the king’s authority firmly, he

rarely compromised it. His zeal for religion and for respectable manners was

very praiseworthy. Perhaps he could have followed better plans to extinguish

the present quarrel; but it must however be said that by the time of his death

there was scarcely any question of Jansenism, whose ashes have been

unwisely rekindled these ten years hence.

92

Deeper analysis of the role of the magistrates must be reserved for the following

chapters. Only by considering all the factors involved in the development of a

political crisis is it possible to discover the true share of the parti janséniste.

222

10

THE PARLEMENT OF PARIS

Social and institutional characteristics of the parlement: the parlement’s jurisdiction; its several

chambers; its venal officers; procedures; attendance; the basoche; social characteristics; rhetorical

education and wealth; self-image. The historiography of the parlement: selfish, politically ambitious

oligarchy, or defender of the people? A renewed emphasis on judicial functions; new approaches; the

study of crises.

A close study of the problematic relationship between the ministry and the

parlement in the 1730s is a highly instructive approach to the structure of perhaps

the single most important area of politics beyond the royal court.

1

Relations with the

sovereign courts were of great importance for the ministry because the parlement

was an indispensable institution both for the administration of justice and for the

registration of royal edicts. In the eighteenth century, the courts rather than the local

or provincial estates were more usually the focal point of opposition to the regime

and their hostility could result in a direct challenge to royal authority. Yet the French

parlements were not simply a potential source of opposition. Like the provincial

estates, they were both government and opposition.

2

SOCIAL AND INSTITUTIONAL CHARACTERISTICS OF

THE PARLEMENT

Although their primary function was as courts of justice, their responsibility for

police, a nebulous ancien régime concept, also gave them a large administrative

responsibility. They had very wide jurisdiction over municipal administration,

provisioning and public order, to cite but a few of the areas.

3

Principally, however,

the parlements of France were courts of appeal, and dealt with a large volume of

litigation about property, criminality and abuses of ecclesiastical justice. As the

guardians of the laws, which in a state such as France had many provincial

variations that had to be respected, the courts also had the important task of

verifying whether new edicts were in conformity with previous legislation and were

likely to be clearly understood. If, as happened most often, all was well, the law

would be registered, perhaps with some modification in the form of an arrêt de

THE PARLEMENT OF PARIS

223

règlement having local validity. But if the judges perceived a problem with a new law,

or tax, the courts could point this out in the form of written remonstrances to the

King in council. Crucially for the ministry, this role in the registration of new laws

meant that the courts could affect the formulation of ministerial policy. The

magistrates’ refusal to register an edict, a tax or a loan, or their subsequent attempts

to drag their legal feet in an attempt to prevent its implementation, or even their

reiterated remonstrances, undermined the status of the law in question and thereby

posed a challenge to the exercise of royal legislative authority. In this respect a study

of the parlement is an essential part of a discussion of the political system at the

centre. Old regime politics cannot be understood without considering its

institutional and social characteristics.

The Paris parlement was a venerable and ancient institution whose origins are

clearer to us than they were to contemporaries. The magistrates themselves liked to

think that their history went back to the Frankish assemblies of the Champ de

Mars, which conducted businesss under the Frankish kings.

4

In reality, the court

was an offshoot of the King’s council during the thirteenth century that took on its

definitive structure by 1345. The court was by then divided into chambers, each

with different judicial responsibilities: a grand’chambre, a chamber of inquiry or

enquêtes and a chamber of requests or requêtes. In geographical terms its range of

jurisdiction was very wide: it was the highest appeal court for central and northern

France, an area that included the Ile de France, the Beauce, Sologne, Berry, the

Auvergne, the Lyonnais, the Maconnais, the Beaujolais, the Nivernais, the Forez,

Picardy, the Champagne, the Brie, Maine, Touraine and Poitou. Other provincial

parlements had much more limited regional jurisdiction, but were just as important

in their own province as was the Paris parlement in its region.

The parlement of Paris was located in the palais de justice, which had once also been

the royal residence before the removal to the Louvre. The palais was a huge complex of

buildings housing not just the parlement but also the conciergerie and the cour des comptes.

The long Mercers’ Gallery was abustle with hawkers and traders and their clients, as

well as prostitutes and nouvellistes. The Great Hall was acceded to by a staircase from the

gallery; it was tremendously impressive by its sheer size, over 75 yards long and 30 yards

wide, and adorned with statues of royalty. It too was athrong with a multitude of traders,

clerks, lawyers and booksellers. The hall of the grand’chambre had a flamboyant gothic

interior, the walls hung with blue velvet showing fleurs de lys, and was divided into two

halves, one with benches for the judges and peers and a raised dais for the King, the

other open to the public.

5

It was here that plenary assemblies of all the chambers of the

parlement took place; and, when the King refused to modify a law that had been the

subject of remonstrances, an enforced registration was held here in a royal ceremony,

known as a lit de justice, the room then being dominated by the King dispensing justice

directly from his throne, which was raised up on the dais, under a regal canopy. The

other chambers were smaller and their topography is less well known, although

contemporary prints give us a good impression of the scene.

The parlement was led by a First President who was usually appointed by the

King from among the three or four most senior presidents à mortier, and contained

THE PARLEMENT OF PARIS

225

a number of prosecuting attorneys known as the gens du roi or the parquet. It was the

First President’s task to lead and control the courts while the gens du roi were expected

to represent the royal legal interest.

6

The magistrates were professional jurists, by now

a mixture of laymen and clerics, all of whom had inherited or purchased their offices.

The senior judges sat in the grand’chambre, where the most important business was

done, such as all cases involving the crown, and where oral pleading took place, in

contrast to the other chambers which worked from written evidence entirely. The

grand’chambre was a court with competence for cases involving the high aristocracy, the

higher officers of the crown and criminal cases concerning those who had a privilege

of being tried in the parlement, and it accepted appeals from cases judged in the first

instance in the other chambers. It also had jurisdiction over appeals comme d’abus

7

—

which was to be a highly significant attribute in this period of theological strife. The

right to accept such appeals was described by d’Argenson as ‘the finest, and even the

only, jewel in the parlement’s crown’.

8

In an appeal comme d’abus, the parlement acted

as a court of appeal for cases in which the appealing party suspected a miscarriage of

justice in the ecclesiastical courts in a way which was contrary to the spirit of royal

legislation. The system was a reflection of royal claims to ultimate control over the

church in jurisdictional matters within France, but there was perpetual conflict

between the bishops and the parlements over this issue. In 1730, the grand’chambre

contained the First President, nine presidents à mortier, thirty-three senior magistrates,

of whom twelve were clerics, several honorary counsellors and presidents (such as

President Hénault then was) and, on special occasions, the princes of the blood with

about fifty lay and ecclesiastical peers.

The five chambers of enquêtes had originally prepared the written testimony for

cases in the grand’chambre, hence the name ‘chamber of inquests’; they now also

judged appeals from lower courts on written evidence. Each of these chambers of

enquêtes was composed of thirty-two counsellors and three presidents. The

magistrates in these courts were for the most part young and less experienced, keen

to divert themselves by tumultuous intervention in affairs of state if they got the

chance. Finally came the two chambers of requêtes whose task it was to to examine

petitions for suits and judge those who had letters of committimus, which is to say a

specific royal grant of the right to be tried by the parlement. Each had three

presidents and the first chamber had fourteen and the second fifteen counsellors

who were usually more mature than the men of the enquêtes. There was, in fact,

another court, the chambre de la tournelle, but it was composed of magistrates drawn

from the other chambers in turn. It judged cases involving the death penalty, and

therefore contained no clerical counsellors.

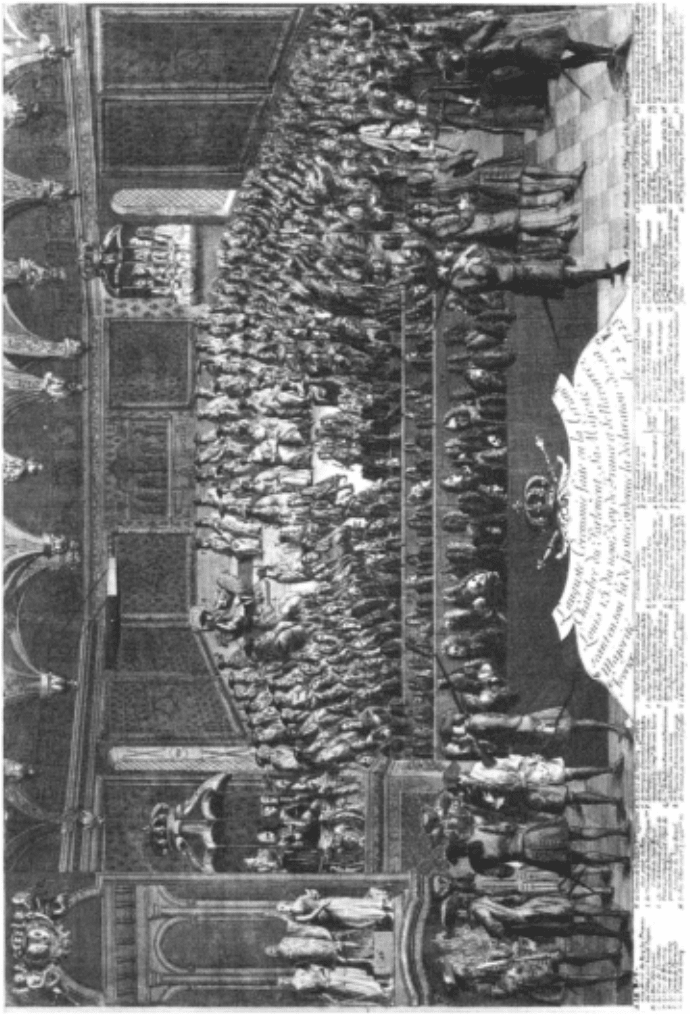

(opposite) Lit de justice at the parlement of Paris on 22 February 1723, on the occasion of Louis

XV reaching his majority. The view shows the magistrates seated in order of rank in the

grand’chambre of the parlement, presided over by the young King seated on a raised dais.

Other plenary assemblies of the courts would take place in the same chamber, in the absence

of the King.

POWER AND POLITICS IN OLD REGIME FRANCE

226

On matters affecting the King’s business, the procedures need to be explained.

9

Relations between the parlement and the ministry were governed by a series of

formal responses. The King’s council came to a decision in the form of an arrêt

signed by the Chancellor and forwarded to the solicitor-general or procureur général as

letters patent by the secretary of state with the department including Paris, who in

this period was Maurepas. The parlement was expected to verify and then register

the letters, which then became law as an edict or declaration. The procureur général

would present it with his own written comments to an assembly of chambers.

There it would be supported by the rapporteur of the court. Nine times out of ten

registration was done on the spot without a problem. If necessary, commissioners

would be appointed to examine it. These were chosen by the First President on the

basis of seniority: fourteen magistrates were from the grand’chambre, nine were

presidents à mortier and another fourteen were from the other seven chambers, two

from each. On a later occasion and in another plenary session the commissioners

would make their recommendations, which would then lead to a ‘debate’ in which

each magistrate would opine in order of seniority. At the end of this process the

parlement had a range of possible responses open to it. It could either enter the law

on its registers as it stood, or with modifications declared in an arrêté. Slightly more

severe would be to request the First President to make supplications on its behalf to

the Chancellor or, more officially, to the King’s council arguing for modifications.

At this stage the council of dispatches would either annul the arrêté from the

parlement, or the Chancellor would reply to the criticisms, usually affirming the

original legislation.

The parlement would then reconvene in a plenary assembly to consider its

response. It might decide to draw up and present a written response in the form of

brief representations or longer remonstrances, in which case the First President

aided by commissioners would compose the remonstrances and present them in

person to the King. Remonstrances tended to focus on matters of law that affected

the special interests of the elite or the people as a whole, the relations between the

temporal and spiritual authorities and encroachments on the legal privileges of the

parlement. The last two areas often overlapped in practice, since the parlement

regarded its cognisance of appeals against ecclesiastical jurisdictions as one of its

most important privileges. The coded language of judicial politics ensured that

remonstrances expressed deep loyalty to the monarch and his sovereign powers, but

the legal arguments they contained were sometimes less respectful. At times it

appears that the magistrates protested their loyalty the better to oppose the King’s

policy. The King might then reply on the spot with a brief speech, followed by a

longer statement from the Chancellor. Another possibility was for the council to

consider the remonstrances and reply at greater length. Usually the reply was more

or less uncompromising, insisting on the respect due to the sovereign power and

command registration. It might take the form of a lettre de jussion. A final resort of the

parlement was to make iterative remonstrances. The most likely royal response was

then to conduct the registration in a lit de justice. This was a majestic ceremonial

occasion on which the King exercised his judicial role in person before the full

THE PARLEMENT OF PARIS

227

parlement, including the peers of the realm. Although opinions were called for, the

magistrates were not expected to voice their discontent and the King was under no

obligation to follow the view of the majority.

Matters usually ended there. Nevertheless, the parlement often chose to

conduct a running battle to evade the provisions of the new law, and might even

confront the government by choosing to go on strike, or even, as a last resort,

resign their offices. But it must not be imagined that this drastic response was

final. Every one of these responses was a finely calculated gesture in the ongoing

relationship between the King’s council and the jurisdiction of the courts. In the

final assessment everyone, both council and magistrates, shared a view of

monarchical authority, and of mysteries of state. It was expected that a

determined show of resistance would lead to a suitable compromise in which

neither side lost face or authority.

Because this process was so finely graded, almost ritualised, it was only likely

to become dangerous in its ultimate stages. In the normal course of events the

First President, aided by the parquet and the more docile senior grand’chambriers,

was in a position to manage the King’s business effectively. If members of a parti

or faction wished to manipulate the response of the courts, they would try to

engineer judgements and institutional responses. This was often hard to do, but

the history of the eighteenth century shows that it was far from impossible. The

exploitation of internal procedures was often crucial to the orchestrated escalation

of an affair. It was important for a faction to ensure that its interests were dealt

with in a plenary session. Sometimes it might be possible to succeed in having one

convened, but this was rare. More likely was the planned introduction of an affair

during an assemblée called for another reason; equally, once an affair had begun,

the necessary assemblée would be called as a matter of course. It was then a

question of arranging to have a particular avis or motion prevail. This was far

from simple and success could not be guaranteed. Clever and sometimes devious

tactics were needed. In debate, the counsellors would range themselves behind

one or more opinions, and so the earlier a motion was introduced the more

chance it had of gaining favour. It was almost indispensable to have members of

the grand’chambre in the plot and preferably the help of one of the few magistrates

to enjoy the confidence of the courts.

10

The final decision of the assembly had to

follow one of the motions. The procedure for arriving at this was very

complicated. When a number of avis had been expressed, in order to reduce them

to a single one, those judges favouring the least popular options would have to

choose a more popular one. The process began with the least popular option and

by a process of elimination two were reached, of which the majority was chosen.

It was then considered binding on the whole company, just as if it had been

expressed unanimously. In 1751 as many as seventeen avis were reduced to one.

11

It appears that suggestions for the wording of an arrêt were accepted out of the

usual order, if someone came up with a suitable expression.

12

If remonstrances

were to be drawn up it was obviously important to be represented on the

commission or to have the favour of the First President. The manipulation of