Brealey, Myers. Principles of Corporate Finance. 7th edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IV. Financial Decisions and

Market Efficiency

14. An Overview of

Corporate Financing

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

much from industry to industry and from firm to firm. But a few statistics will do

no harm as long as you keep these difficulties in mind.

Table 14.2 shows the aggregate balance sheet of all manufacturing corporations

in the United States in 2001. If all manufacturing corporations were merged into

one gigantic firm, Table 14.2 would be its balance sheet.

Assets and liabilities in Table 14.2 are entered at book, that is, accounting values.

These do not generally equal market values. The numbers are nevertheless in-

structive. The table shows that manufacturing corporations had total book assets

of $4,903 billion. On the right-hand side of the balance sheet, we find total long-

term liabilities of $1,717 billion and stockholders’ equity of $1,951 billion.

So what was the book debt ratio of manufacturing corporations in 2001? It de-

pends on what you mean by debt. If all liabilities are counted as debt, the debt ra-

tio is .60:

This measure of debt includes both current liabilities and long-term obligations.

Sometimes financial analysts focus on the proportions of debt and equity in long-

term financing. The proportion of debt in long-term financing is

The sum of long-term liabilities and stockholders’ equity is called total capitaliza-

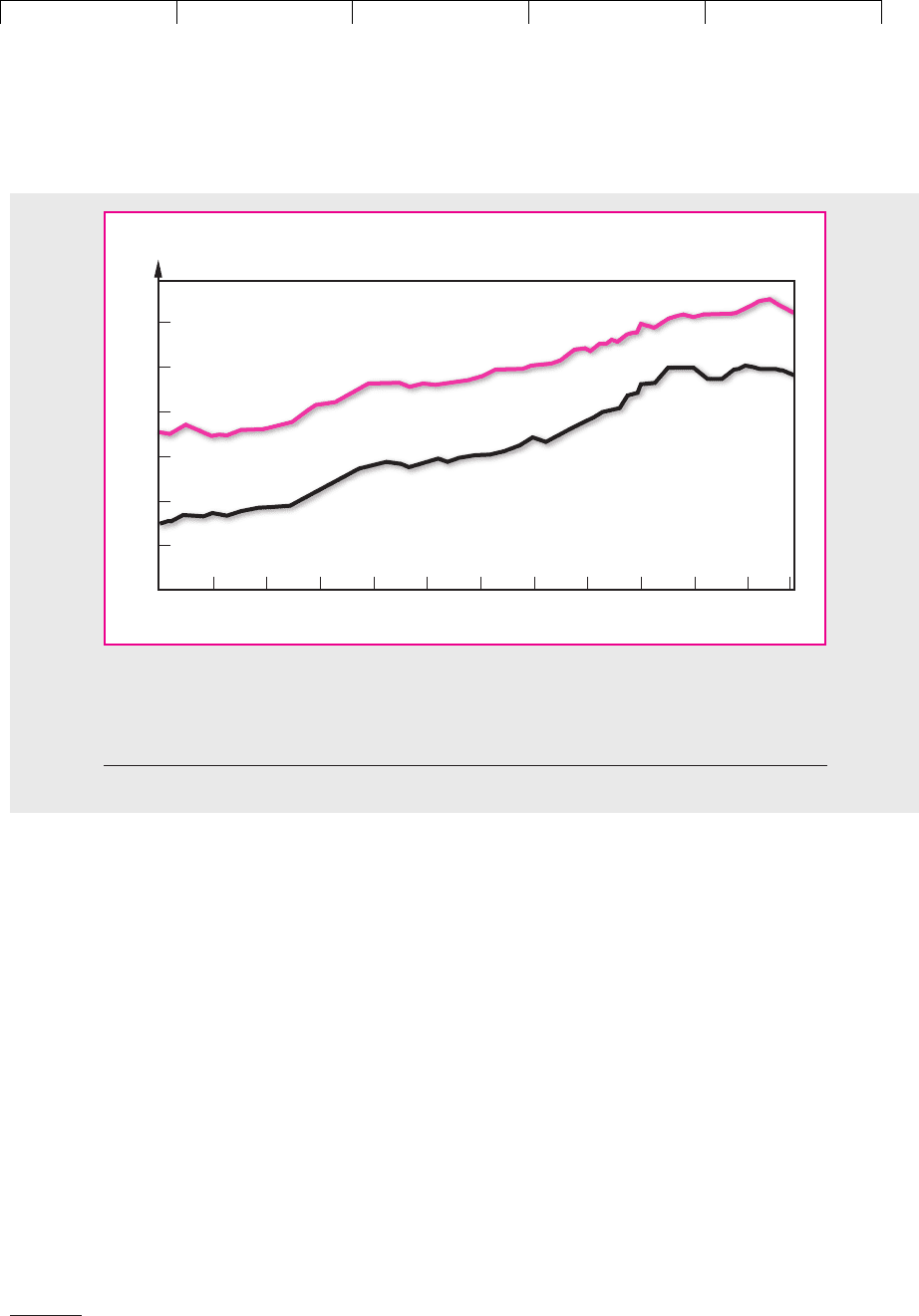

tion. Figure 14.1 plots these two ratios from 1954 to 2001. There is a clear upward

trend. But before we conclude that industry is becoming weighed down by a crip-

pling debt burden, we need to put these changes in perspective.

Long-term liabilities

Long-term liabilities ⫹ stockholders’ equity

⫽

1,717

1,717 ⫹ 1,951

⫽ .47

Debt

Total assets

⫽

1,234 ⫹ 1,717

4,903

⫽ .60

380 PART IV Financing Decisions and Market Efficiency

Current assets

†

$1,547 Current liabilities

†

$1,234

Fixed assets $2,361 Long-term debt $1,038

Less depreciation 1,166 Other long-term

liabilities

‡

679

Net fixed assets 1,195 Total long-term

liabilities 1,717

Other long-term Stockholders’ equity 1,951

assets 2,160

Total assets

§

$4,903 Total liabilities and

stockholders’ equity

§

$4,903

TABLE 14.2

Aggregate balance sheet for manufacturing corporations in the United States, 1st quarter, 2001 (figures in

$ billions)*.

*Excludes companies with less than $250,000 in assets.

†

See Table 30.1 for a breakdown of current assets and liabilities.

‡

Includes deferred taxes and several miscellaneous categories.

§

Columns may not add up because of rounding.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Quarterly Financial Report for Manufacturing, Mining and Trade Corporations, 1st Quarter, 2001

(www.census.gov/csd/qfr

).

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IV. Financial Decisions and

Market Efficiency

14. An Overview of

Corporate Financing

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

1990 versus 1920 Debt ratios in the 1990s, though clearly higher than in the early

postwar period, are no higher than in the 1920s and 1930s. You could argue that

Figure 14.1 starts from an abnormally low point.

4

Inflation Some of the upward movement in Figure 14.1 may have reflected infla-

tion, which was especially rapid—by U.S. standards—throughout the 1970s and

early 1980s. Rapid inflation means that the book value of corporate assets falls behind

the actual value of those assets. If corporations were borrowing against actual value,

it would not be surprising to observe rising ratios of debt-to-book asset values.

To illustrate, suppose that you bought a house 10 years ago for $60,000. You fi-

nanced the purchase in part with a $30,000 mortgage, 50 percent of the purchase

price. Today the house is worth $120,000. Suppose that you repay the remaining bal-

ance of your original mortgage and take out a new mortgage of $60,000, which is

again 50 percent of current market value. Your book debt ratio would be 100 percent.

The reason is that the book value of the house is its original cost of $60,000 (we as-

sume no depreciation). An analyst having only book values to work with would ob-

serve that 10 years ago your book debt ratio was only 50 percent and might conclude

CHAPTER 14

An Overview of Corporate Financing 381

1954 1958

10

Debt ratio,

percent

Year

20

30

40

50

60

1962 1966 1970 1974 1978 1982 1986 1990 1994 1998 2001

Debt versus total assets

Debt versus total long-term financing

FIGURE 14.1

Average debt ratios for manufacturing corporations in the United States have increased in the

postwar period. However, note that these ratios compare debt with the book value of total assets

and total long-term financing. The actual value of corporate assets is higher as a result of inflation.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Quarterly Financial Report for Manufacturing, Mining and Trade Corporations,

various issues.

4

See Figure 1.3 on p. 25 in R. A. Taggart, Jr., “Secular Patterns in the Financing of U.S. Corporations,” in

B. M. Friedman (ed.), Corporate Capital Structures in the United States, University of Chicago Press, 1985.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IV. Financial Decisions and

Market Efficiency

14. An Overview of

Corporate Financing

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

that you had decided to “use more debt.” But you have no more debt relative to the

actual value of your house.

Despite such qualifications, it’s still the case that many U.S. corporations are car-

rying a lot more debt than they used to. Should we be worried? It’s true that higher

debt ratios mean that more companies will fall into financial distress if a serious re-

cession hits the economy. But all companies live with this risk to some degree, and

it does not follow that less risk is better. Finding the optimal debt ratio is like find-

ing the optimal speed limit. We can agree that accidents at 30 miles per hour are

generally less dangerous than accidents at 60 miles per hour, but we do not there-

fore set the speed limit on all roads at 30. Speed has benefits as well as risks. So does

debt, as we will see in Chapter 18.

There is no God-given, correct debt ratio, and if there were, it would change. It

may be that some of the new tools that allow firms to manage their risks have made

higher debt ratios practicable.

International Comparisons Corporations in the United States are generally

viewed as having less debt than many of their foreign counterparts. That was

surely true in the 1950s and 1960s. Now it is not so clear.

Rajan and Zingales examined the balance sheets of a large sample of publicly

traded firms in the seven largest industrialized countries. They calculated debt ra-

tios using both book and market values of shareholders’ equity. (The book value of

debt was assumed to approximate market value.) A taste of their results is given in

Table 14.3. Notice that the debt ratios for the United States sample fall in the mid-

dle of the pack.

International comparisons of this sort are always muddied by differences in ac-

counting methods. For example, German companies show pension liabilities as a

debtlike obligation on their balance sheets, with no offsetting entry for pension as-

sets.

5

They also report “reserves” separately from equity. These reserves do not cover

any specific obligations but serve as equity for a rainy day. Reserves might be drawn

down to offset a future drop in operating earnings, for example. (This would be un-

acceptably creative accounting in the United States.) When Rajan and Zingales

crossed out the pension liabilities and added back reserves to equity, the adjusted debt

ratios for German companies dropped to the low levels reported in Table 14.3.

382 PART IV

Financing Decisions and Market Efficiency

Debt to Total Capital

Book, Market,

Book Adjusted Market Adjusted

Canada 39% 37% 35% 32%

France 48 34 41 28

Germany 38 18 23 15

Italy 47 39 46 36

Japan 53 37 29 17

United Kingdom 28 16 19 11

United States 37 33 28 23

TABLE 14.3

Median debt-to-total-capital ratios in

1991 for samples of traded companies

in the major countries. Debt includes

short- and long-term debt. Total

capital is defined as the sum of all debt

and equity. The adjusted figures

correct for some international

differences in accounting.

Source: R. G. Rajan and L. Zingales, “What

Do We Know about Capital Structure?

Some Evidence from International Data,”

Journal of Finance 50 (December 1995),

pp. 1421–1460.

5

United States companies show a net liability only if the pension plan is underfunded.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IV. Financial Decisions and

Market Efficiency

14. An Overview of

Corporate Financing

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Corporations raise cash in two principal ways—by issuing equity or by issuing

debt. The equity consists largely of common stock, but companies may also is-

sue preferred stock. As we shall see, there is a much greater diversity of debt

securities.

We start our brief tour of corporate securities by taking a closer look at common

stock. Table 14.4 shows the common equity of H.J. Heinz Company. The maximum

number of shares that can be issued is known as the authorized share capital; for

Heinz it was 600 million shares. If management wishes to increase the number of

authorized shares, it needs the agreement of shareholders to do so. By May 2000

Heinz had already issued 431 million shares, and so it could issue 169 million more

without further shareholder approval.

Most of the issued shares were held by investors. These shares are said to be is-

sued and outstanding. But Heinz has also bought back 84 million shares from in-

vestors. Repurchased shares are held in the company’s treasury until they are ei-

ther canceled or resold. Treasury shares are said to be issued but not outstanding.

The issued shares are entered into the company’s books at their par value. Each

Heinz share had a par value of $.25. Thus the total book value of the issued shares

was 431 ⫻ $.25 ⫽ $108 million. Par value has little economic significance.

6

Some

companies issue shares with no par value. In this case, the stock is listed in the ac-

counts at an arbitrarily determined figure.

The price of new shares sold to the public almost always exceeds par value.

The difference is entered in the company’s accounts as additional paid-in capi-

tal or capital surplus. Thus, if Heinz had sold an additional 100,000 shares at $40

a share, the common stock account would have increased by 100,000 ⫻ $.25 ⫽

$25,000, and the capital surplus account would have increased by 100,000 ⫻

$39.75 ⫽ $3,975,000.

Heinz distributed about 50 percent of its earnings as dividends. The remainder

was retained in the business and used to finance new investments. The cumulative

amount of retained earnings was $4,757 million.

CHAPTER 14

An Overview of Corporate Financing 383

14.2 COMMON STOCK

Common shares ($.25 par value per share) $ 108

Additional paid-in capital 304

Retained earnings 4,757

Treasury shares (2,920)

Other adjustments (652)

Net common equity $1,596

Note:

Authorized shares 600

Issued shares, of which: 431

Outstanding shares 347

Treasury shares 84

TABLE 14.4

Book value of common stockholders’ equity of H.J.

Heinz Company, May 3, 2000 (figures in millions).

Sources: H.J. Heinz Company, Annual Reports.

6

Because some states do not allow companies to sell shares below par value, par value is generally set

at a low figure.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IV. Financial Decisions and

Market Efficiency

14. An Overview of

Corporate Financing

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

The next entry in the common stock account shows the amount that the com-

pany has spent on repurchasing its common stock. The repurchases have reduced

the stockholders’ equity by $2,920 million. Finally, there is an entry for other ad-

justments, principally currency losses stemming from Heinz’s foreign operations.

We would rather not get into these accounting adjustments here.

Heinz’s net common equity had a book value in May 2000 of $1,596 million.

That works out at 1,596/347 ⫽ $4.60 per share. But in May 2000, Heinz’s shares

were priced at about $35 each. So the market value of the common stock was 347 mil-

lion ⫻ $35 ⫽ $12.1 billion, over $10 billion higher than book.

Ownership of the Corporation

A corporation is owned by its common stockholders. Some of this common stock

is held directly by individual investors, but the greater proportion belongs to fi-

nancial institutions such as banks, pension funds, and insurance companies. For

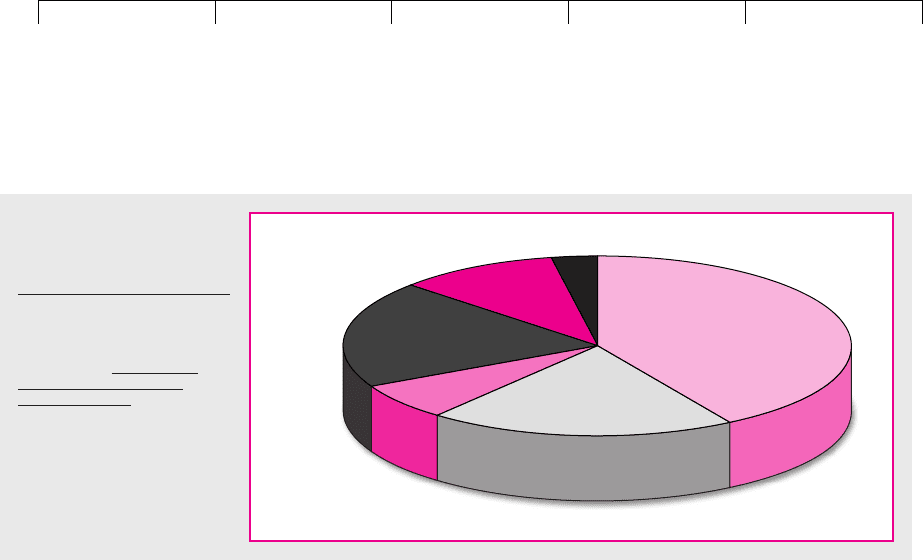

example, look at Figure 14.2. You can see that in the United States just over 60 per-

cent of common stock is held by financial institutions, with pension funds and mu-

tual funds each holding about 20 percent.

What do we mean when we say that these stockholders own the corporation?

The answer is obvious if the company has issued no other securities. Consider

the simplest possible case of a corporation financed solely by common stock, all

of which is owned by the firm’s chief executive officer (CEO). This lucky

owner–manager receives all the cash flows and makes all investment and oper-

ating decisions. She has complete cash-flow rights and also complete control rights.

These rights are split up and reallocated as soon as the company borrows

money. If it takes out a bank loan, it enters into a contract with the bank promising

to pay interest and eventually repay the principal. The bank gets a privileged, but

limited, right to cash flows; the residual cash-flow rights are left to the stockholder.

The bank will typically protect its claim by imposing restrictions on what the

firm can or cannot do. For example, it may require the firm to limit future borrow-

ing, and it may forbid the firm to sell off assets or to pay excessive dividends. The

stockholders’ control rights are thereby limited. However, the contract with the

384 PART IV

Financing Decisions and Market Efficiency

Other

Households

Rest of

world

Mutual

funds, etc.

Insurance

companies

Pension funds

FIGURE 14.2

Holdings of corporate

equities, 2000.

Source: Board of Governors of

the Federal Reserve System,

Division of Research and Statis-

tics, Flow of Funds Accounts

Table L.213 at www.federal

reserve.gov/releases/z1/

current/data.htm.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IV. Financial Decisions and

Market Efficiency

14. An Overview of

Corporate Financing

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

bank can never restrict or determine all the operating and investment decisions

necessary to run the firm efficiently. (No team of lawyers, no matter how long they

scribbled, could ever write a contract covering all possible contingencies.

7

) The

owner of the common stock retains the rights of control over these decisions. For

example, she may choose to increase the selling price of the firm’s products, to hire

temporary rather than permanent employees, or to construct a new plant in Miami

Beach rather than Hollywood.

8

Ownership of the firm can of course change. If the firm fails to make the prom-

ised payments to the bank, it may be forced into bankruptcy. Once the firm is un-

der the “protection” of a bankruptcy court, shareholders’ cash-flow and control

rights are tightly restricted and may be extinguished altogether. Unless some res-

cue or reorganization plan can be implemented, the bank will become the new

owner of the firm and will acquire the cash-flow and control rights of ownership.

(We discuss bankruptcy in Chapter 25.)

There is no law of nature that says residual cash-flow rights and residual con-

trol rights have to go together. For example, one could imagine a situation where

the debtholder gets to make all the decisions. But this would be inefficient. Since

the benefits of good decisions are felt mainly by the common stockholders, it

makes sense to give them control over how the firm’s assets are used.

We have focused so far on a firm that is owned by a single stockholder. In many

countries, such as Italy, Hong Kong, or Mexico, there is generally a dominant stock-

holder who controls 20 percent or more of the votes of even the largest corpora-

tions.

9

There are also a few major businesses in the United States that are controlled

by one or two large stockholders. For example, at the beginning of 2001 Bill Gates

owned 21 percent of the common stock of Microsoft as well as being chairman and

chief executive. However, such concentration of control is the exception. Owner-

ship of most major corporations in the United States is widely dispersed.

The common stockholders in widely held corporations still have the residual

rights over the cash flows and have the ultimate right of control over the company’s

affairs. In practice, however, their control is limited to an entitlement to vote, either

in person or by proxy, on appointments to the board of directors, and on other crucial

matters such as the decision to merge. Many shareholders do not bother to vote.

They reason that, since they own so few shares, their vote will have little impact on

the outcome. The problem is that, if all shareholders think in the same way, they cede

effective control and management gets a free hand to look after its own interests.

Voting Procedures and the Value of Votes

If the company’s articles of incorporation specify a majority voting system, each di-

rector is voted upon separately and stockholders can cast one vote for each share

that they own. If a company’s articles permit cumulative voting, the directors are

voted upon jointly and stockholders can, if they wish, allot all their votes to just

CHAPTER 14

An Overview of Corporate Financing 385

7

Theoretical economists therefore stress the importance of incomplete contracts. Their point is that contracts

pertaining to the management of the firm must be incomplete and that someone must exercise residual

rights of control. See O. Hart, Firms, Contracts, and Financial Structure, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1995.

8

Of course, the bank manager may suggest that a particular decision is unwise, or even threaten to cut

off future lending, but the bank does not have any right to make these decisions.

9

See R. La Porta, F. Lopez-de-Silanes, and A. Shleifer, “Corporate Ownership around the World,” Jour-

nal of Finance 54 (1999), pp. 471–517.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IV. Financial Decisions and

Market Efficiency

14. An Overview of

Corporate Financing

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

one candidate.

10

Cumulative voting makes it easier for a minority group among

the stockholders to elect directors who will represent the group’s interests. That is

why some shareholder groups campaign for cumulative voting.

On many issues a simple majority of votes cast is sufficient to carry the day, but

the company charter may specify some decisions that require a supermajority of,

say, 75 percent of those eligible to vote. For example, a supermajority vote is some-

times needed to approve a merger. Managers, who believe that their jobs may be

threatened by a merger, are often anxious to persuade shareholders to agree that

the charter should be amended to require a supermajority vote.

11

The issues on which stockholders are asked to vote are rarely contested, partic-

ularly in the case of large, publicly traded firms. Occasionally, there are proxy con-

tests in which the firm’s existing management and directors compete with out-

siders for effective control of the corporation. But the odds are stacked against the

outsiders, for the insiders can get the firm to pay all the costs of presenting their

case and obtaining votes.

Usually companies have one class of common stock and each share has one vote.

Occasionally, however, a firm may have two classes of stock outstanding, which

differ in their right to vote. Suppose that a firm needs fresh equity capital, but its

present shareholders do not wish to relinquish their control of the firm. The exist-

ing shares could be labeled “class A,” and then “class B” shares with limited vot-

ing privileges could be issued to outsiders.

Both classes of shareholders would have the same cash-flow rights but they

would have different control rights. For example, each A share could have five

votes, the B shares only one. However, the two classes would have identical claims

to the corporation’s assets, earnings, and dividends.

Holders of the A shares would have extra voting power to toss out bad man-

agement or to force management to adopt value-enhancing investment or operat-

ing policies. But both the A and B shares should benefit equally from such changes,

since the two classes of shares have identical cash-flow rights. So here’s the ques-

tion: If everyone gains equally from better management, why would investors be

prepared to pay more for one class of shares than for another? The only plausible

reason is private benefits captured by the A shares. For example, a holder of a block

of A shares might be able to obtain a seat on the board of directors or access to

perquisites provided by the company. (How about a ride to Bermuda on the cor-

porate jet?) The A shares might have extra bargaining power in an acquisition. The

A shares might be held by another company, which could use its voting power and

influence to secure a business advantage. These are some of the reasons why the A

shares could sell for a higher price.

These private benefits of control seem to be much larger in some countries than

others. For example, Luigi Zingales has looked at companies in the United States

and Italy that have two classes of stock. In the United States investors were on av-

erage prepared to pay an extra 11 percent for the shares with the superior voting

386 PART IV

Financing Decisions and Market Efficiency

10

For example, suppose there are five directors to be elected and you own 100 shares. You therefore have

a total of 5 ⫻ 100 ⫽ 500 votes. Under the majority voting system, you can cast a maximum of 100 votes

for any one candidate. Under a cumulative voting system, you can cast all 500 votes for your favorite

candidate.

11

See, for example, R. M. Stulz, “Managerial Control of Voting Rights: Financing Policies and the Mar-

ket for Corporate Control,” Journal of Financial Economics 20 (January–March 1988), pp. 25–54.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IV. Financial Decisions and

Market Efficiency

14. An Overview of

Corporate Financing

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

“Not so long ago,” wrote The Economist maga-

zine, “shareholder friendly companies in Switzer-

land were as rare as Swiss admirals. Safe behind

anti-takeover defences, most managers treated

their shareholders with disdain.” However, The

Economist perceived one encouraging sign that

these attitudes were changing. This was a proposal

by the Union Bank of Switzerland (UBS) to change

the rights of its equity holders.

UBS had two classes of shares—bearer shares,

which are anonymous, and registered shares, which

are not. In Switzerland, where anonymity is prized,

bearer shares usually traded at a premium. UBS’s

bearer shares had sold at a premium for many years.

However, there was another important distinction

between the two share classes. The registered

shares carried five times as many votes as an equiva-

lent investment in the bearer shares. Presumably at-

tracted by this feature, an investment company, BK

Vision, began to accumulate a large position in the

registered shares, and their price rose to a 38 per-

cent premium over the bearer shares.

At this point UBS announced its plan to merge

the two classes of share, so that the registered

shares would become bearer shares and would

lose their superior voting rights. Since all UBS’s

shares would then sell for the same price, UBS’s an-

nouncement led to a rise in the price of the bearer

shares and a fall in the price of the registered.

Martin Ebner, the president of BK Vision, ob-

jected to the change, complaining that it stripped

the registered shareholders of some of their voting

rights without providing compensation. The dis-

pute highlighted the question of the value of supe-

rior voting stock. If the votes are used to secure

benefits for all shareholders, then the stock should

not sell at a premium. However, a premium would

arise if holders of the superior voting stock ex-

pected to secure benefits for themselves alone.

To many observers UBS’s proposal was a wel-

come attempt to prevent one group of sharehold-

ers from profiting at the expense of others and to

unite all shareholders in the common aim of maxi-

mizing firm value. To others it represented an at-

tempt to take away their rights. In any event, the

debate over the proposal was never fully resolved,

for UBS shortly afterward agreed to merge with

SBC, another Swiss bank.

rights, but in Italy the average premium for a vote was 82 percent.

12

The Finance

in the News box describes a major dispute in Switzerland over the value of supe-

rior voting rights.

Even when there is only one class of shares, minority stockholders may be at a dis-

advantage; the company’s cash flow and potential value may be diverted to man-

agement or to one or a few dominant stockholders holding large blocks of shares. In

the United States, the law protects minority stockholders from blatant or extreme ex-

ploitation. Minority stockholders in other countries do not always fare so well.

13

387

12

L. Zingales, “What Determines the Value of Corporate Votes?” Quarterly Journal of Economics 110

(1995), pp. 1047–1073; and L. Zingales, “The Value of the Voting Right: A Study of the Milan Stock Ex-

change,” Review of Financial Studies 7 (1994), pp. 125–148. The data for the United States were for the pe-

riod 1984–1990. This was the height of the leveraged buyout boom, when the value of control was likely

to have been unusually large. An earlier study that looked at the period 1940–1978 found a premium of

only 4 percent. See R. C. Lease, J. J. McConnell, and W. H. Mikkelson, “The Market Value of Control in

Publicly-Traded Corporations,” Journal of Financial Economics 11 (April 1983), pp. 439–471.

13

International differences in the opportunities for dominant shareholders to exploit their position is

discussed in S. Johnson et al., “Tunnelling,” American Economic Review 90 (May 2000), pp. 22–27.

FINANCE IN THE NEWS

A CONTEST OVER VOTING RIGHTS

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IV. Financial Decisions and

Market Efficiency

14. An Overview of

Corporate Financing

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Example Financial economists sometimes refer to the exploitation of minority

shareholders as tunneling; the majority shareholder tunnels into the firm and ac-

quires control of the assets for himself. Let us look at an example of tunneling

Russian-style.

To grasp how the scam works, you first need to understand reverse stock splits.

These are often used by companies with a large number of low-priced shares. The

company making the reverse split simply combines its existing shares into a

smaller (and, hopefully, more convenient) number of new shares. For example, the

shareholders might be given 2 new shares in place of the 3 shares that they cur-

rently own. As long as all shareholdings are reduced by the same proportion, no-

body gains or loses by such a move.

However, the majority shareholder of one Russian company realized that the re-

verse stock split could be used to loot the company’s assets. He therefore proposed

that existing shareholders receive 1 new share in place of every 136,000 shares they

currently held.

14

Why did the majority shareholder pick the number “136,000”? Answer: because

the two minority shareholders owned less than 136,000 shares and therefore did

not have the right to any shares. Instead they were simply paid off with the par

value of their shares and the majority shareholder was left owning the entire com-

pany. The majority shareholders of several other companies were so impressed

with this device that they also proposed similar reverse stock splits to squeeze out

their minority shareholders.

Needless to say such blatant exploitation would not be permitted in the United

States.

Equity in Disguise

Common stocks are issued by corporations. But a few equity securities are issued not

by corporations but by partnerships or trusts. We will give some brief examples.

Partnerships Newhall Land and Farming is a master limited partnership which

owns large tracts of real estate, mostly in southern California. You can buy

“units” in this partnership on the New York Stock Exchange, thus becoming a

limited partner in Newhall. The most the limited partners can lose is their in-

vestment in the company.

15

In this and most other respects, the Newhall part-

nership units are just like the shares in an ordinary corporation. They share in

the profits of the business and receive cash distributions (like dividends) from

time to time.

Partnerships avoid corporate income tax; any profits or losses are passed

straight through to the partners’ tax returns. Offsetting this tax advantage are var-

ious limitations of partnerships. For example, the law regards a partnership merely

as a voluntary association of individuals; like its partners, it is expected to have a

limited life. A corporation, on the other hand, is an independent legal “person” that

can, and often does, outlive all its original shareholders.

388 PART IV

Financing Decisions and Market Efficiency

14

Since a reverse stock split required only the approval of a simple majority of the shareholders, the pro-

posal was voted through.

15

A partnership can offer limited liability only to its limited partners. The partnership must also have

one or more general partners, who have unlimited liability. However, general partners can be corpora-

tions. This puts the corporation’s shield of limited liability between the partnership and the human be-

ings who ultimately own the general partner.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IV. Financial Decisions and

Market Efficiency

14. An Overview of

Corporate Financing

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Trusts and REITs Would you like to own a part of the oil in the Prudhoe Bay field

on the north slope of Alaska? Just call your broker and buy a few units of the Prud-

hoe Bay Royalty Trust. British Petroleum (BP) set up this trust and gave it a royalty

interest in production from BP’s share of the Prudhoe Bay revenues. As the oil is

produced, each trust unit gets its share of the revenues.

This trust is the passive owner of a single asset: the right to a share of the rev-

enues from BP’s Prudhoe Bay production. Operating businesses, which cannot be

passive, are rarely organized as trusts, though there are exceptions, notably real es-

tate investment trusts, or REITs (pronounced “reets”).

REITs were created to facilitate public investment in commercial real estate;

there are shopping center REITs, office building REITs, apartment REITs, and

REITs that specialize in lending to real estate developers. REIT “shares” are traded

just like common stocks.

16

The REITs themselves are not taxed, so long as they pay

out at least 95 percent of earnings to the REITs’ owners, who must pay whatever

taxes are due on the dividends. However, REITs are tightly restricted to real estate

investment. You cannot set up a widget factory and avoid corporate taxes by call-

ing it a REIT.

Preferred Stock

Usually when investors talk about equity or stock, they are referring to common

stock. But Heinz has also issued $139,000 of preferred stock, and this too is part of

the company’s equity. Despite its name, preferred stock provides only a small part of

most companies’ cash needs and it will occupy less time in later chapters. However,

it can be a useful method of financing in mergers and certain other special situations.

Like debt, preferred stock offers a series of fixed payments to the investor. The

company can choose not to pay a preferred dividend, but in that case it may not

pay a dividend to its common stockholders. Most issues of preferred are known as

cumulative preferred stock. This means that the firm must pay all past preferred div-

idends before common stockholders get a cent. If the company does miss a pre-

ferred dividend, the preferred stockholders generally gain some voting rights, so

that the common stockholders are obliged to share control of the company with the

preferred holders. Directors are also aware that failure to pay the preferred divi-

dend earns the company a black mark with investors, so they do not take such a

decision lightly.

CHAPTER 14

An Overview of Corporate Financing 389

16

There are also some private REITs, whose shares are not publicly traded.

17

In practice this handover of assets is far from straightforward. Sometimes there may be thousands of

lenders with different claims on the firm. Administration of the handover is usually left to the bank-

ruptcy court (see Chapter 25).

14.3 DEBT

When companies borrow money, they promise to make regular interest payments

and to repay the principal. However, this liability is limited. Stockholders have the

right to default on the debt if they are willing to hand over the corporation’s assets

to the lenders. Clearly, they will choose to do this only if the value of the assets is

less than the amount of the debt.

17