Boyer George R. An Economic History of the English Poor Law, 1750-1850

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Poor Relief in Industrial

Cities

257

spite

the

disturbance caused

by the

1846

Act,

removal

in the

West

Rid-

ing seems,

in

general,

to

have been kept

as a

reserve weapon."

29

3.

The

System

of

Nonresident Relief

The Settlement

Law, and in

particular

the

power

of

removal,

led to the

development

of

another institution that enabled industrial cities

to

pass

some

of

their relief costs

on to

nonindustrial unions, namely,

the

system

of nonresident

relief.

When

a

nonsettled person applied

for relief,

indus-

trial areas often contacted

the

person's parish

of

settlement

and

asked

to

be reimbursed

for any

relief payments granted.

If the

parish

of

settle-

ment agreed

to pay the

nonresident

relief, the

urban parish

did not

remove

the

person

who

applied

for relief. At

first glance,

the

system

of

nonresident relief does

not

appear

to

fit

in

with my hypothesis that there

was

not an

oversupply

of

labor

in

rural areas.

Why

would rural parishes

have been willing

to pay

relief

to

persons residing

in

industrial areas

rather than allow them

to be

removed, unless

the

rural areas were

already plagued with

an

overabundance

of

labor?

The key

to

understand-

ing

the

system

of

nonresident relief

is

the

same as

the key to

understand-

ing urban parishes' removal policies.

It

concerns

the

demographic

and

occupational characteristics

of

those persons receiving nonresident

re-

lief. The

persons that urban parishes were most anxious

to

remove, such

as widows

or

handloom weavers, were also

the

persons that rural

par-

ishes least wanted returned,

for

they were bound

to be a

permanent

charge whatever their parish

of

residence. Moreover,

it was

probably

cheaper

for a

rural parish

to pay for the

relief

of a

widow

and her

children

or a

handloom weaver

in an

urban area than

to

have them

removed back

to the

rural parish, because

the job

opportunities

for

women, children,

and

workers

in

declining industries were better

in

urban areas.

The

chairman

of the

London Committee

for the

Relief

of

the Manufacturing Districts remarked

in 1827

that

not

only were

the

employment opportunities

for

handloom weavers better

in

urban than

in

rural areas, there

was

also some chance that displaced handloom weav-

ers

in

urban areas could become powerloom weavers (Parl. Papers

1826-

29

The Settlement

Law was

further amended

in

1861

and

1865.

The

1861

act

reduced

the

time

of

continuous residence necessary

to

become irremovable

to

three years.

The 1865

Union Chargeability

Act

made nonsettled persons irremovable after one year's continu-

ous residence

and

"took

all

powers over settlement

and

rating

out of the

hands

of the

parish

and

made them

the

responsibility

of the

union

and its

board

of

guardians" (Rose

1976:

30-1).

258

An

Economic History of the

English Poor

Law

7:

V,

238). Another category

of

persons who often received nonresident

relief

was "old or

infirm people

who had

gone

to

live with younger

or

fitter relatives

in the

industrial towns" (Rose

1965: 281).

Such persons

required less relief

if

they were living

in an

urban area with relatives than

if they were returned

to a

rural parish.

I suspect that

the

share

of

persons receiving nonresident relief

who

were unemployed workers

in

nondeclining industries

was

small. There

were situations, however, where

it

made sense

for

rural parishes

to

grant

nonresident relief

to

able-bodied workers.

If the

urban workers were

only temporarily unemployed,

it

would cost

the

rural parish less

in the

long

run to pay

part

of the

workers' relief

for a

short time than

to

allow

them

to be

returned. This was especially true

if

the workers were

put on

short time rather than laid

off.

Only

if a

rural parish experienced

a

scarcity

of

labor during peak seasons

did it

make sense

to

allow

its

nonresident workers

to be

removed.

The discussion

in the

preceding paragraph assumed that unemployed

nonsettled workers would

be

removed from urban areas

if

they

did not

receive nonresident

relief. I

argued above, however, that industrial

ar-

eas were usually willing

to

relieve nonsettled workers

in

order

to

retain

an adequate supply

of

labor. They often attempted

to

bluff unions into

granting nonresident relief

to

able-bodied workers

by

threatening

to

remove persons that they

in

fact

had no

intention

of

removing (Ashforth

1979:

314).

There

is

evidence that threatened unions were often willing

to call

the

industrial cities' bluffs

by

refusing

to pay for

temporarily

unemployed workers.

For

instance,

the

Leicester Union decided

in 1844

"only

[to]

repay relief administered

to its

non-resident paupers

in

cases

of sickness, infirmity,

or old age"

(Ashforth 1979:

315). In

other words,

Leicester refused

to pay

nonresident relief

to

able-bodied workers.

Wycombe Union agreed to pay nonresident relief only

for

persons "main-

tained

in the

workhouse," which,

of

course, excluded unemployed

or

underemployed workers (Ashforth

1979: 315). In sum, the

parishes

of

settlement agreed

to pay

nonresident relief only

for

those paupers whom

they thought

the

industrial cities would

in

fact remove.

The effect

of the

system

of

nonresident relief

on

urban relief expendi-

tures probably was small because in most cases nonresident relief

was

not

a substitute

for

relief paid

by

industrial parishes. Persons

who

received

nonresident relief typically would have been removed

in its

absence,

rather than relieved. The major savings to industrial

cities,

therefore, was

the cost

of

removing recipients

of

nonresident

relief. If

nonresident relief

Poor

Relief

in

Industrial

Cities

259

had not existed, the number of removals from industrial areas would have

increased, and the share of persons removed who were likely to be a

permanent charge on the parish would have been significantly larger than

the numbers obtained from Table 8.6.

4.

Urban Attitudes Toward the Poor Law Amendment Act

It was mentioned earlier in this chapter that Poor Law officials in most

industrial cities refused to follow the recommendation of the Poor Law

Commission in 1834 that no outdoor relief be granted to adult able-

bodied males. The same persons who bitterly opposed the implementa-

tion of the New Poor Law

in

their

cities,

however, supported

its

implemen-

tation in the agricultural south and east of England. In their opinion, the

policy of "less eligibility enforced through the workhouse system could

not be sensibly applied to the North, however beneficial it might prove to

be in the South" (Edsall

1971:

48). Some members of Parliament from the

industrial northwest went so far as to argue during the debate over the

Poor Law Amendment Act that the north should be excluded from the

act s provisions.

There is no doubt, however, that industrial areas were eager for the

workhouse test to be enforced in the south and east. Before 1834, manu-

facturers had complained that the lax administration of the Poor Law in

agricultural regions hindered the migration of labor to the industrial

cities.

Edmund Ashworth, a Lancashire manufacturer, wrote in 1834

that "under the present law, . . . [s]o highly do the poor value their

parish allowance, which from long habit they consider their lawful inheri-

tance, and so thoroughly do they understand the laws regarding their

settlements, that scarcely any prospects of bettering their condition will

induce them to remove" (Pad. Papers 1835: XXXV, 212). Similarly,

manufacturer Robert Greg blamed "the operation of the poor laws in

binding down the labourers to their respective parishes" for the "diffi-

culty in obtaining labourers at extravagant wages in these northern coun-

ties"

(Parl. Papers 1835: XXXV, 213).

Ironically, trade was booming in the northern textile cities in the

summer of 1834 when the Poor Law Amendment Act was being de-

bated. Not only was there a serious shortage of labor in the textile-

30

For instance, Edward Baines, MP from Leeds, stated that "at Manchester and other

places, there was no necessity for the exercise of that power, the parishes being well

administered" (quoted in Brundage 1978: 66-7).

260 An Economic History of

the English Poor

Law

producing areas at this time, there was also an "outbreak of trades

unionism," spurred by the strong position of labor (Redford 1964:

113).

31

The labor shortage was exacerbated by the Factory Acts of

1833,

which curtailed the use of child labor in the factories (Redford

1964:

101). Several textile manufacturers, notably Edmund Ashworth

and Robert Greg, responded to the labor scarcity by writing members

of the Royal Poor Law Commission and asking them to encourage the

migration of surplus rural laborers to the industrial north. Ashworth

wrote to Edwin Chadwick that he was "most anxious that every facility

be given to the removal of labourers from one county to another ac-

cording to the demand for labour; this would have a tendency to equal-

ize wages as well as prevent in degree some of the turn-outs [that is,

strikes] which have been of late so prevalent." Greg wrote that "we are

now in want of labour," and that unless labor could be obtained from

the low-wage south, "any farther demand for labour would still further

increase the unions, drunkenness, and high wages" (Parl. Papers 1835:

XXXV, 213).

Assistant Commissioner James Kay, in an 1835 report to the Poor Law

Commissioners, estimated that an additional 45,000 "mill hands" would

be required in the Lancashire cotton district in the next two years.

Because the neighboring counties could supply no more labor, the only

available sources were the rural south and Ireland (Parl. Papers 1835:

XXXV, 186-8). Kay recommended that the commissioners appoint an

agent in Manchester to "form a medium of communication between the

mill-owners, seeking a supply of labour, and the Commissioners, who,

by means of their Assistant Commissioners in the south, may make a

proper selection of the workmen, and transmit them directly to the mills

for which they are required" (Parl. Papers 1835: XXXV, 189).

In response to the manufacturers' suggestions, the Poor Law Commis-

sioners sent a circular letter in March 1835 to manufacturers in districts

where "there existed the greatest demand for labourers," offering "to

those who had a demand for labourers to make the circumstance known

31

Unionism experienced an "exceptional and short-lived [burst] of expansion" from 1829

to 1834 (Hunt

1981:

193). The cotton spinners were particularly successful in organizing

during this period. The expansion culminated in the formation of the Grand National

Consolidated Trades Union in 1833. The GNCTU collapsed in midsummer 1834, but it

claimed to have 800,000 members during its short life (Hunt 1981: 202-3). As can be

seen from the quotes later in the paragraph, manufacturers were hopeful that the unions

could be broken by an influx of labor from the south, although, ironically, the union

movement had collapsed by the time the first migrants were sent to the northwest.

Poor

Relief

in

Industrial

Cities

261

in parishes containing families willing to migrate, from whom such a

selection could be made as might meet the wishes of the employer"

(Pad. Papers 1835: XXXV, 22). Migration offices were opened in Man-

chester and Leeds in the summer of 1835. From then until May 1837,

when a recession ended the demand for labor, approximately 4,700

laborers were aided in their migration from the rural south to northern

industrial cities.

32

The majority of migrants came from East Anglia, in

particular Suffolk, and 84% of them went to Lancashire, Cheshire, and

the West Riding (Redford 1964: 107-8).

One of the themes of this book is that farmers and manufacturers used

their local political power to institute a system of poor relief which

involved a transfer of income from other local taxpayers to themselves.

The information in this section suggests that the use of political power to

reduce costs of production occurred at the national as well as the local

level. The northwest's support of the Poor Law Amendment Act was

based on the belief that rural-urban wage gaps were caused by the lax

administration of poor relief in the south, which discouraged surplus

labor from migrating to the labor-scarce northwest. The elimination of

outdoor relief in the south would lead to an increase in migration to

industrial areas. Northern manufacturers did not institute the call for

Poor Law reform, but they quickly recognized reform as a method to

attract labor and hence to lower wages and reduce the power of labor

unions. Although northern MPs supported the implementation of the

workhouse test in the rural south, they refused to implement it in their

own parishes, arguing that it was not suited to the problem of cyclical

unemployment.

Their strategy proved only partly successful. Most industrial unions

continued to grant outdoor relief to able-bodied workers at least into the

1850s, despite attempts by the Poor Law Commission to stop the prac-

tice.

But the expected large increase in migration from the rural south

was not forthcoming. Manufacturers, like the Poor Law Commissioners,

had significantly overestimated the effect of rural parishes' use of out-

door relief on labor mobility, and therefore overestimated the extent of

32

During the same period, 6,400 individuals from the rural south left England for overseas

destinations as part of a Poor Law emigration scheme (Redford 1964: 108-9). Why did

the Poor Law Commission sponsor an emigration scheme, given the scarcity of labor in

the northwest? According to Redford (1964: 110), "the Commissioners themselves pre-

ferred the home migration scheme," but the sending parishes "favored emigration,

because this made it more difficult for the paupers to return or to be brought back to

their place of settlement."

262 An Economic History of the

English Poor

Law

surplus labor in the agricultural south. Moreover, those persons who

migrated out of the rural south after 1834 generally went either to Lon-

don or overseas. London was more accessible than the northwest, and

southern farm workers "preferred to seek work with which they were at

least partly familiar. Outdoor work . . . and domestic service met their

needs far better than the factories, and there was ample employment of

this kind in London" (Hunt

1981:

157).

33

The major sources of migrants

to the industrial northwest both before and after 1834 were the rural

areas within Lancashire, Yorkshire, and Cheshire, and, in the case of

Lancashire cities, Ireland (Redford 1964: 183-4).

5. Conclusion

The payment of poor relief to temporarily unemployed workers oc-

curred in urban as well as agricultural parishes. Indeed, urban relief

administrators continued granting outdoor relief to able-bodied workers

for at least two decades after the passage of the Poor Law Amendment

Act. The use of the Poor Law as an unemployment insurance system

enabled manufacturers, who dominated local politics in most industrial

cities,

to pass some of the costs of maintaining factory workers not

required during cyclical downturns to non-labor-hiring taxpayers. I esti-

mated in Section 1 that this income transfer to manufacturers averaged

£50,000 to £60,000 per year.

In addition, the Settlement Law and in particular the power of re-

moval enabled cities to pass most of the cost of maintaining nonsettled

migrants who were likely to be a permanent charge on the relief rolls to

their parishes of settlement and to the migrants themselves (by keeping

them from applying for relief). The importance of the Settlement Law to

urban parishes is shown by the effect on relief expenditures of the Poor

Removal Act of 1846, which made any nonsettled person who lived in

the same parish for five years irremovable. "By destroying the deterrent

effect of the threat of removal and ... by undermining the system of

non-resident

relief,"

the 1846 act caused a sharp increase in urban

33

Southern farm workers' preference for London over the industrial northwest was not

because of differences in wages between the two

regions.

In

1839

and

1849

nominal wages

of bricklayers' laborers were equal in London and Manchester, 18s. per week. London

data are from Schwarz

(1986:

38); Manchester data are from Bowley

(1900b:

310). Crafts

(1982:

62) and Williamson

(1987:

652) agree that in the

1840s

the cost of

living was

slightly

higher in London than in the industrial northwest. Real wages of low-skilled workers

therefore were slightly higher in the industrial northwest than in London.

Poor Relief

in

Industrial

Cities

263

unions' relief expenditures (Ashforth 1985: 78-9, 81). For the five years

ended Lady Day 1861, irremovable paupers accounted for 62.2% of

relief expenditures in Bradford, 60.8% of expenditures in Manchester,

and 39.6% of expenditures in Sheffield (Ashforth 1985: 81).

The Settlement Law and the power of removal saved urban industrial

unions in Lancashire, Cheshire, and the West Riding perhaps £50,000 to

£80,000 per year. If manufacturers paid 35% of the poor rate, as was

assumed above, then the Settlement Law saved them £17,500 to £28,000

per year. The total income transfer from rural taxpayers, non-labor-

hiring urban taxpayers, and nonsettled urban workers to manufacturers

therefore was on the order of £67,500 to £88,000 per year.

34

Given that

savings rates varied across income classes, the income transfer caused

capital accumulation to increase by perhaps £15,000 to £20,000 per

year.

35

However, the Settlement Law also might have had a negative effect

on industrialization. If migration from the agricultural south to the north-

west was slowed by rural workers' fear of removal, then the Settlement

Law fostered a misallocation of labor and slowed the rate of economic

growth. It was determined in Section 2, however, that the selective use

of the power of removal by textile manufacturing cities should not have

deterred able-bodied young adults from migrating to urban areas. More-

over, urban Poor Law unions often granted relief to temporarily unem-

ployed nonsettled workers, which reduced the risk associated with migra-

tion and therefore should have increased the number of migrants. In

sum, urban poor relief had a positive (but small) impact on the English

economy during the first half of the nineteenth century.

34

This estimate was obtained by adding the estimated annual transfer from non-labor-

hiring urban taxpayers to manufacturers resulting from the use of the Poor Law as an

unemployment insurance system (£50,000-£60,000) and the estimated annual transfer

from rural taxpayers and nonsettled urban workers to manufacturers resulting from the

Settlement Law (£17,500-£28,000).

35

1 assume that the savings rate of manufacturers, farmers, and landlords was 30%, that

the savings rate of non-labor-hiring taxpayers was 5-10%, and that workers did not

save.

Crafts (1985: 124-5) estimated that the savings rate of farmers and landlords was

30%

and that the savings rate out of nonagricultural nonlabor income was "not . . . less

than 23 per cent." I assume that textile manufacturers' savings rate was the same as that

of farmers and landlords. Von Tunzelmann (1985: 215) and Crafts (1985: 124) conclude

that "saving out of

wages

was zero." See also Fishlow

(1961:

36). Feinstein

(1978:

76, 93)

estimated that fixed capital formation averaged £50.5 million per annum in the 1840s,

and that

25%

of total investment (£12.6 million) was devoted to industrial buildings and

machinery. If one-third of industrial investment took place in Lancashire, Cheshire, and

the West Riding, then the Poor Law caused capital formation in manufacturing to

increase by 0.4-0.5%.

264

An Economic History of

the

English

Poor Law

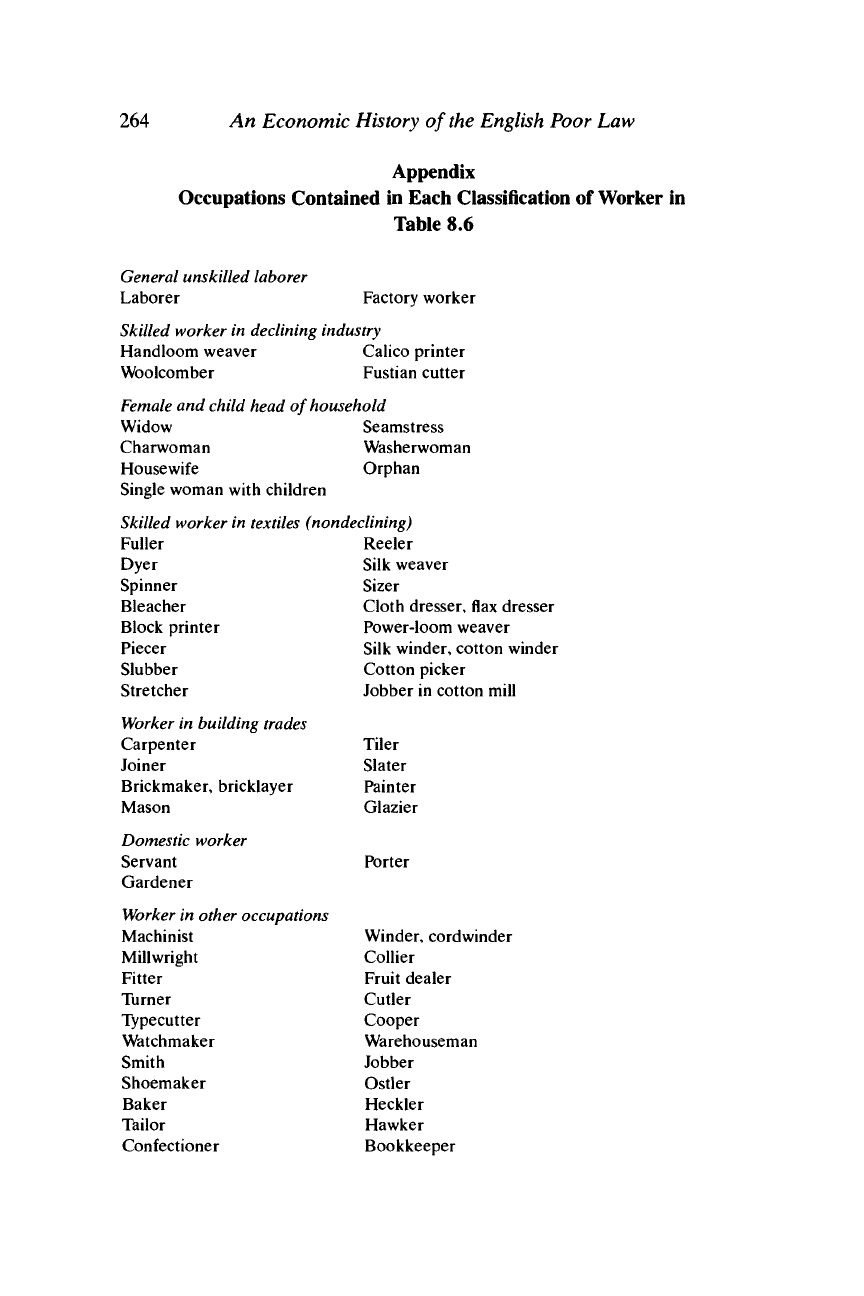

Appendix

Occupations Contained

in

Each Classification

of

Worker

in

Table

8.6

General unskilled laborer

Laborer

Factory worker

Skilled worker

in

declining industry

Handloom weaver Calico printer

Woolcomber Fustian cutter

Female

and

child head

of

household

Widow Seamstress

Charwoman Washerwoman

Housewife Orphan

Single woman with children

Skilled worker

in

textiles (nondeclining)

Fuller

Dyer

Spinner

Bleacher

Block printer

Piecer

Slubber

Stretcher

Worker

in

building trades

Carpenter

Joiner

Brickmaker, bricklayer

Mason

Domestic worker

Servant

Gardener

Worker

in

other occupations

Machinist

Millwright

Fitter

Turner

Typecutter

Watchmaker

Smith

Shoemaker

Baker

Tailor

Confectioner

Reeler

Silk weaver

Sizer

Cloth dresser, flax dresser

Power-loom weaver

Silk winder, cotton winder

Cotton picker

Jobber

in

cotton mill

Tiler

Slater

Painter

Glazier

Porter

Winder, cordwinder

Collier

Fruit dealer

Cutler

Cooper

Warehouseman

Jobber

Ostler

Heckler

Hawker

Bookkeeper

CONCLUSION

1.

Summary

of

the Argument

The

aim of

this book has been

to

provide

an

explanation

for the

develop-

ment

and

persistence

of

policies providing outdoor relief

for

able-bodied

workers,

and to

examine

the

effect

of

such policies

on

certain aspects

of

the rural economy.

The

book

is an

extension

of

the revisionist analysis of

the

Old

Poor

Law

begun

by

Mark Blaug

in

1963.

As

such,

it

builds

on

the pioneering work

of

Blaug

(1963;

1964), Daniel Baugh (1975),

and

Anne Digby (1975; 1978). These authors rejected

the

traditional litera-

ture's conclusion that outdoor relief policies

had

disastrous conse-

quences

on the

rural labor market. Their arguments concerning

the

effects

of the

Poor

Law on

labor

are

convincing,

and

leave little else

to

be addressed.

The

revisionists' explanation

for the

adoption

and

persis-

tence

of

outdoor

relief,

however,

is not as

well developed.

To

date,

no

study

has

appeared that adequately explains

the

economic role

of out-

door relief

and the

reason

why it

developed

in the

last third

of the

eighteenth century.

Three issues must

be

resolved

in

order

to

determine

the

economic role

of outdoor

relief. The

first concerns

the

system's origins.

Was

outdoor

relief

an

emergency response

to the

high food prices

of 1795, as the

traditional literature claimed,

or

was

it a

response

to

long-term changes

in

the

economic environment? Evidence from local studies

and

available

data

on

relief expenditures suggest that outdoor relief became wide-

spread during

the

period from

1760 to 1795. The

year

1795 was not a

watershed

in the

administration

of

poor

relief. I

contend that parishes

adopted outdoor relief policies

in

response

to two

major changes

in the

economic environment

in the

south

and

east

of

England:

the

decline

in

allotments

of

land

for

agricultural laborers,

and the

decline

in

cottage

industry. Before

the

late eighteenth century,

the

typical agricultural

la-

265

266

An

Economic History of the

English Poor

Law

borer's family

had

three sources

of

income:

a

small plot

of

land

for

growing food; wage labor

in

agriculture during peak seasons;

and

slack-

season employment (yearlong

for

women

and

children)

in

cottage indus-

try.

The

income earned from

two of

these sources declined sharply after

1760.

Parishes responded

to the

loss

in

income

by

guaranteeing season-

ally unemployed laborers

a

minimum weekly income

in the

form

of

poor

relief.

This raises

the

second issue:

Why was

outdoor relief adopted over

other methods

for

dealing with

the

decline

in

income, especially

in

grain-

producing areas? To answer this question

an

economic model was devel-

oped that yielded

the

conditions under which implicit labor contracts

including seasonal layoffs

and

outdoor relief were

an

efficient method

for securing

an

adequate peak-season labor force.

The two key

determi-

nants

of the

form

of

farmers' cost-minimizing labor contracts were

the

extent

of

seasonal fluctuations

in the

demand

for

labor

(a

function

of

crop mix),

and the

size

of

the contribution

of

non-labor-hiring taxpayers

to

the

poor rate. Contracts containing seasonal layoffs

and

outdoor

relief were cost-minimizing

in the

grain-producing southeast, while full-

employment contracts were cost-minimizing

in the

pasture-farming west

and north.

Even

in

grain-producing areas, however,

the

importance

of

outdoor

relief was

a

function

of the

share

of the

poor rate paid

by

taxpayers

who

did

not

hire labor, such

as

family farmers, artisans,

and

shopkeepers.

The smaller

the

share

of the

poor rate paid

by

labor-hiring farmers,

the

larger

the

number

of

layoffs during slack seasons, other things equal.

If

labor-hiring farmers paid

the

entire cost

of

relieving unemployed work-

ers (that

is, if

they were perfectly experience-rated), full-employment

contracts were cost-minimizing even

in

grain-producing areas. This

is a

very important result. Seasonality

by

itself would

not

have caused

the

development

of

outdoor

relief.

What was required was

a

combination of

seasonality

and a tax

system that allowed farmers

to be

subsidized

by

other parish taxpayers.

A

further implication

of the

fact that some

ratepayers subsidized others under

the

Poor

Law is

that

the

administra-

tion

of

relief must have been affected

by the

political makeup

of the

parish.

The

widespread

use of

outdoor relief suggests that most rural

parishes were dominated

by

labor-hiring farmers,

and

available

evi-

dence supports this conclusion.

The hypotheses advanced

in

Chapters

1 and 3

concerning

the

adop-

tion

and

persistence

of

outdoor relief were tested using data

for

311

rural