Boardman J., Hammond N.G. L. The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 3, Part 3: The Expansion of the Greek World, Eighth to Sixth Centuries BC

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CRETAN LAWS

AND

SOCIETY

245

adoption assumed fresh significance. As the clansmen's rights became

more formal,

so the

special responsibilities

of an

heir

to an

estate

increased. Until free testamentary disposition became established,

the

head

of

an

oikos

must have wished

to

ensure

a

responsible succession

from within the

oikos.

So the system of adoption, through the

betaireiai

apparatus, became

a

state responsibility.

In

the Code, adoption might

be made without restriction; and

a

formal ceremony was held

in the

market-place before

the

assembled citizens,

the

adopter presenting

a

sacrificial victim and

a

quantity

of

wine

to

his

hetaireia.

2i

The provisions

of

the Gortyn Code which concern an heiress are of

considerable interest and importance for the social and legal historian.

25

The members

of the

tribe

of the

heiress still maintained rights

of

marriage to the heiress when, in certain circumstances, she did not marry

the next of

kin.

A rule of tribal endogamy was still thus preserved, with

the

epiballontes

belonging

to

one exogamous clan group who normally

intermarried with another exogamous group, called their

kadestai.

The

terms

epiballontes

and

kadestai

signify the bonds of obligation formed by

kinship on the one hand, by marriage on the other. This archaic system,

observed by anthropologists in various parts of the world in more recent

times,

depended upon

the

continuous intermarriage

of

exogamous

cross-cousins, relatives being classified according

as"

they belonged to one

group

or

the other.

The Code defines

an

heiress

as a

daughter without

a

father and

a

brother

of

the same father. She could inherit her father's property but

had to marry the next of kin. The immediate next of kin was the paternal

uncle.

If

there were several

of

them, the oldest had prior claim. When

there were several heiresses and paternal uncles, they were obliged

to

marry in order of

age.

In the absence of paternal uncles, the heiress then

had

to

marry her paternal cousin; and,

if

there were several, the oldest

had prior claim. Should there be several heiresses and paternal cousins,

they were obliged to marry in order of age of the brothers.

In

this way

the material interests

of

a patriarchal household were being protected

by state legislation,

now

encouraging marriage between

kin of the

household

as

compared with cross-cousin marriage between clan

groups. However, these newer trends were still contradicted by other

stipulations deriving from older surviving matrilineal customs. Women

still

had

significant rights

to the

tenure

of

property

and

land.

For

example, when the heiress and

a

male claimant were too young to marry,

the heiress could have the house and half the income from the property,

the other half going

to

the claimant. When there was no claimant,

an

heiress

of

marriageable age could hold the property and marry

as

she

24

X.

33-XI.

23; D

164, JO-I.

25

VII. 15-IX. 24; XII. 6-I9; D 164, 18-27.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

246 3SK- CRETAN LAWS AND SOCIETY

wished within the tribe; and if no tribesman presented

himself,

she was

free to accept an offer from anyone else.

Marriage was allowed between a free woman and a serf (vn.

1—10).

The children were free or unfree according to whether the serf lived

with the free woman or vice versa. It follows that

a

woman who married

twice might have free and unfree children. We can assume that

marriages between free men and serf women were not recognized. Both

husband and wife were allowed to divorce if either wished; and there

were consequent rules in these cases, as also when wife or husband died,

about the disposal of property

(11.

45—

in. 16). A father had power over

children and division of property among them. A mother had power

over her own property. When a father died, the houses in the town and

anything in the houses (if not occupied by a serf belonging to the

country estate), along with the sheep and larger animals not belonging

to a

serf,

went to the sons. The remaining property was fairly divided,

sons receiving two parts, daughter one part each. When a mother

died, her property was similarly divided. Houses occupied by serfs

belonged, as did the serfs, to the estate and were regarded as income-

producing property in which daughters shared. Sons had clear preference

over daughters in division of inheritance; but there is some evidence

to indicate that women had received more generous treatment before

the publication of the Code.

26

The terminology of the Code includes titles of certain age-grades of

free citizens. A boy or girl before puberty was described as

anoros

or

anebos,

after- puberty as

ebion,

ebionsa

and

orima.

An adult citizen after the

age probably of about twenty was called a

dromeus

(runner), implying

his right (denied to serfs) to gymnastic exercises. Conversely, an

apodromos

was a minor, not yet old enough to claim the right.

27

The

youth were organized in

agelai

(herds). When they graduated from the

agelai

they were obliged to marry at the same time, apparently at a public

ceremony for those of

the

same age-grade also belonging to groups with

ties of intermarriage with other groups.

28

These customs persisted long

after the publication of the Code, despite more recent developments

favouring the autonomous family and property interests indicated in the

Code

—

especially by the exception to the general rule of collective

marriage made in the case of a minor allowed to marry the heiress so

as to safeguard household interests. This care to ensure succession in

the male line explains the right of a minor to marry an heiress as an

exception to older rules; and also why she could marry at the early age

of twelve (vn. 35-40; xn. 17-21).

26

IV. 23~V. 9; D 164, 2O-I.

27

vn. 30, 3;ff, 37, 54;

VI

"- 39. 4

6

; *'• '9J

c

f- I"

1

- Cret. n v. 25A 7 (Axus).

28

Strabo 482-4; cf. Ath. iv. 143; Nic. Dam. fr. 115; Heradid. Pont. 3.4; D 161, 7-17.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CRETAN LAWS AND SOCIETY 247

The term

apageloi

was probably confined

to

adolescents just before

their entry into

agelai,

which were similar to the bands of citizen novices

in other states; but Cretan youths did not enter

agelai

until the end

of

their seventeenth year.

29

Aristotle

{Pol.

1264a) explains that the Cretans gave

to

their servile

population the same rights as they had themselves, except that they were

forbidden gymnastic exercises and the possession

of

arms. This helps

us to understand why an earlier system of patriarchal slavery which we

may define as 'serfdom' (in the sense that

a

servile peasantry was tied

to the soil and paid tribute

to

overlords) endured

for

centuries after

commercial chattel slavery (with slaves bought

and

sold like other

commodities) had become a dominant form of servitude in other states.

This does not mean that a transition from collective tenure of ancestral

estates to narrower circles of proprietorship did not cause modifications

in the serf system from time

to

time and perhaps from place

to

place;

and

it was no

doubt affected

in

various ways

by the

simultaneous

development of chattel slavery. Consequently the ancient evidence from

terminology relevant

to

servile populations

is

varied, complex and

by

no means easy

of

analysis. The problem

is

exemplified

in

the Gortyn

Code which has two servile terms which can be translated as 'serf and

'slave' respectively:

the

woikeus

(implying

a

person attached

to the

oikos);

and the

dolos

(i.e. slave). The difficulty

is

that these two words

are

not

used strictly

to

define

two

different conditions

of

servility.

However, various contexts make clear that there were two different

servile statuses. Dolos

is

sometimes used with

the

same meaning

as

woikeus,

sometimes with

the

meaning

of

chattel slave.

The

clearest

example

of

the latter usage occurs

in a

regulation about buying slaves

in the market-place. Again, as we have seen, a penalty is laid down

for

rape against a domestic slave, so that one rule applies to

a

serf,

another

to a slave. The Code also demonstrates that

a

free citizen could pledge

his person

as

security

for

payment

of

debt/he

was

then called

a

katakeimenos.

A

nenikamenos

was

a

free man condemned

for

debt and

handed over in bondage to a creditor. Although these persons lost their

freedom

as

citizens they were

not

reduced

to the

category

of

chattel

slaves.

The

woikeus

had access

to

the law-courts, though

he

was probably

represented

by

his master and perhaps his rights

at

law were less than

the rights of a free man. Serfs had other rights which distinguished their

status from that of chattel slaves. They had the right of tenure of houses

in which they lived and their contents. They could also possess cattle

as a right. In order to pay fines assessed for various offences in the Code

they must have possessed money. A serf family had

a

recognized social

29

Hesych. s.v. anaytXos; Sch. Eur. Ale. 989; D 162, 175-9, 285-6.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

248 35K- CRETAN LAWS AND SOCIETY

and legal status since a serf could marry and divorce; and a serf wife

could possess her own moveable property, including livestock, which

reverted to her in case of divorce. When she married, she changed

masters; and when divorced she returned to her former master or his

relatives.

Between the minority class of free citizens and the servile there were

a number of other social groups whose exact status is difficult to define.

The

apetairoi

were such a class of people who must have included, as

the name implies, all those excluded from

hetaireiai

or closed corpora-

tions of

male

citizens, and therefore from the privileges of membership,

including rights of citizenship. Within this category were perhaps

members of communities subjected to a city-state but allowed a kind

of autonomy. In an early fifth-century

B.C.

inscription from Gortyn a

certain Dionysius was granted privileges including exemption from

taxation, the right to sue in the same courts as citizens and a house and

land in Aulon, which might have been subjected to Gortyn, with its

own local government and taxes. The

apetairoi

were certainly inferior

insofar as they were not full citizens, but they must have had a relatively

free economic status, at least to the extent that they were neither bonded

nor enslaved.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CHAPTER

3SW

EUBOEA AND THE ISLANDS

W.

G. G.

FORREST

I. EUBOEA, 7OO—5OO B.C.

If the

end of

the Lelantine

War (CAH

m.i

2

, 760-3) shed

the

light

of peace

on a

troubled Euboea,

it

brought none

of

any kind

to its

history. We

are

left with

a

Chalcis still stubbornly unyielding

of

any

archaeological truth, an abandoned Lefkandi, a prospering New Eretria

and the other cities, so far as we know, much as they were before. But

none

of

them,

not

even Eretria, figures more than occasionally

and

usually accidentally

in

anything that

can be

called

the

mainstream

of

Greek history, nor can much

be

said

of

their domestic affairs.

The aristocracies under which the war had been fought, and won

or

lost, were

not

unaffected

by the

challenges that faced aristocracies

elsewhere and before

600

a tyrant, Tynnondas (an interestingly Boeotian

name) imposed himself on

the

'Euboeans' (Plut. Sol. 14)

and

others,

Antileon and Phoxus,

on

Chalcis (Arist. Pol. 1304a, 1316a), but Tynn-

ondas is remembered only

for

his name, Antileon and Phoxus for their

departures not their presence (one was succeeded by an oligarchy,

the

other by

a

democracy). But what Aristotle, our source

for

both, meant

by' oligarchy' or 'democracy' is unclear. The only firm fact is that when

the Athenians won a famous victory over the Chalcidians about

506

and,

in effect, took over Chalcis, they settled 4,000

of

their citizens

on the

lands

of the

Hippobotae,

the

'Horse-breeders',

a

name that

has a

sufficiently traditional aristocratic flavour

to

suggest that whatever

tyrannies, oligarchies or democracies had gone before did little to shake

Chalcidians from their inherited ways (Hdt.

v.

74—7).

Eretrian politics should have been, perhaps were, more interesting.

The physical shock

of

the move from Lefkandi,

if

such

it

was, and

be

it

or

be

it

not in some way connected with defeat in the Lelantine War,

together with

the

long-term results

of

colonial expansion

and

conse-

quent commercial success should have done something to the fabric of

Eretrian society, but there again we have only the name

of

one tyrant,

Diagoras,

who 'put

down

the

oligarchy

of the

Hippeis

[the

'Horsemen']',

and the

statement that these Hippeis were still

in the

249

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

250

-

EUBOEA AND THE ISLANDS

T3

J

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

EUBOEA, 7OO—5OO B.C. 251

political saddle around 550 (Arist. Pol. 1306a; Ath. Pol. 15.2). Either

Diagoras comes after 550 or he, like Antileon and Phoxus, had no

lasting success. A very fragmentary shipping-law of about 525 (as well

as giving us the title of the chief magistrate, the

archos)

testifies to a

continuing interest in the sea as does Eretria's contribution of five ships

to help the Ionians in their revolt in 499, a contribution which may have

earned her a temporary, though not very plausible claim to 'thalasso-

cracy' between 500 and 490.

1

The distribution of her pottery overseas

may also owe as much to seamanship as to the talents of her potters.

2

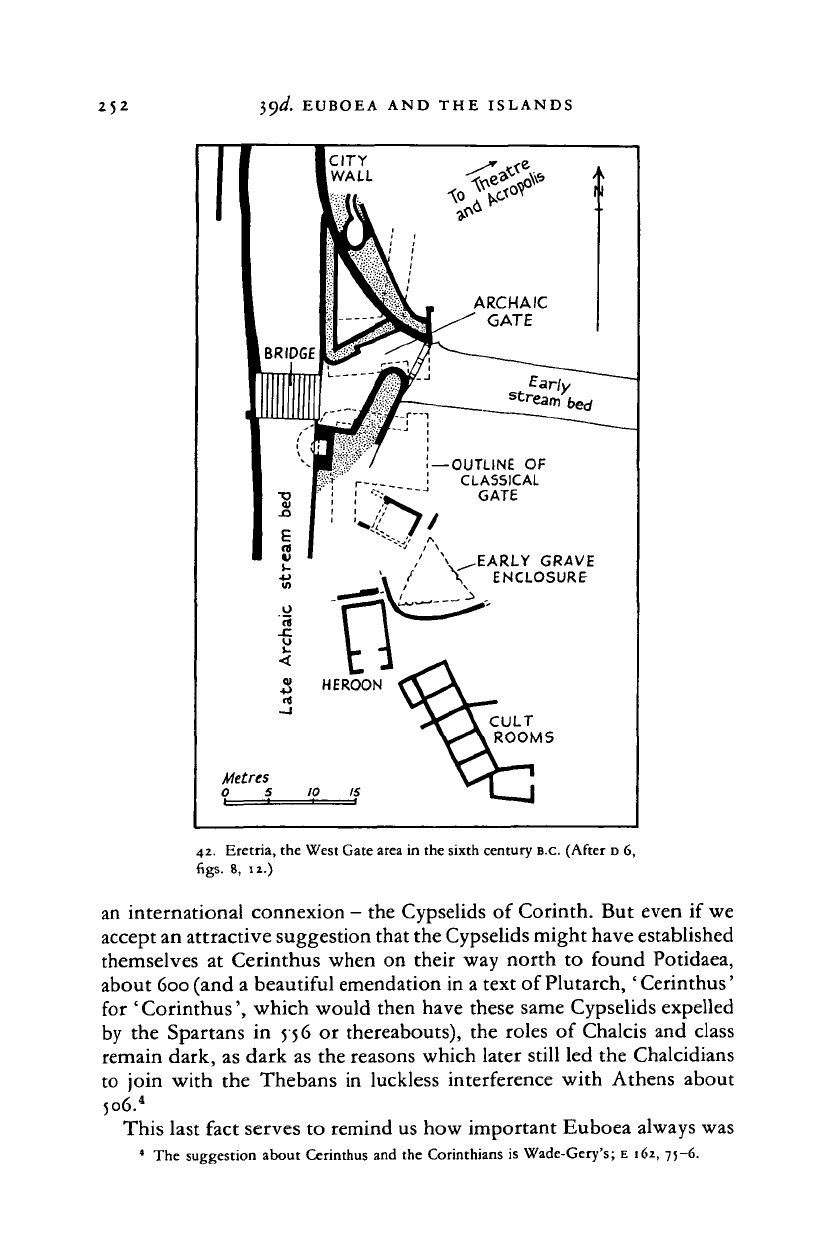

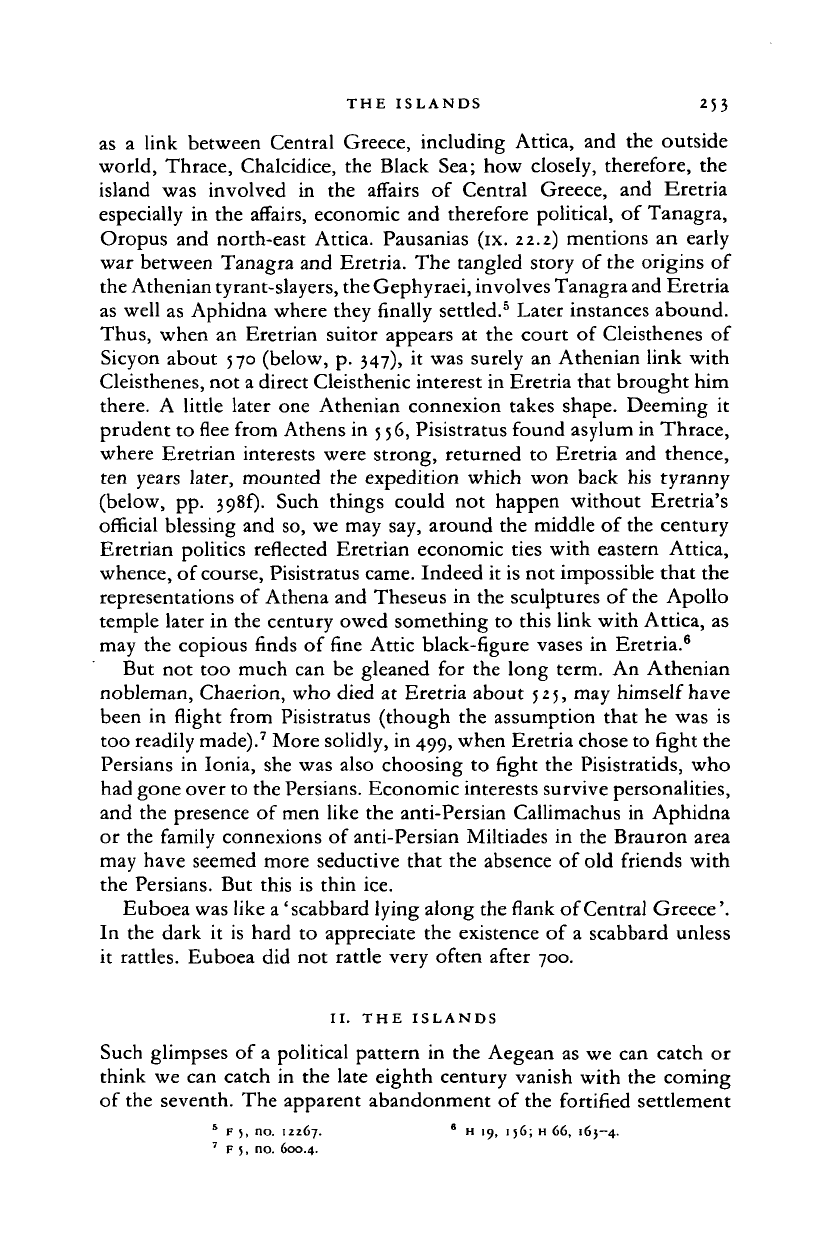

But the really hard fact is the building programme in the new city

that begins around 700. A wall was constructed including a striking,

indeed for its date unparalleled, defensive complex, the so-called West

Gate (fig. 42), cutting the main road south from Chalcis, and behind

it rose public buildings, sacred and profane, including a temple of

Dionysus and a fine sixth-century temple to Apollo Daphnephorus,

rich in sculpture (see below), while in other parts of the city remains of

private houses and material from graves show continuing and growing

wealth, broken only in the end by the Persian sack of 490.

3

But from

whose pockets the money had come for all this, how it was extracted

from them and how, precisely, it had got into them, we can only guess.

Foreign relationships are more substantial at first sight, but no more

coherent. Chalcis continued to colonize in the north, adventures which

ended with a joint foundation with Andros at Sane and thence produced

a dispute about further expansion to Acanthus, about 655. The dispute

was settled in favour of Andros when, of the arbitrators, Samos and

Erythrae voted for her, and Paros for Chalcis, which shows no more

than that associations of the Lelantine War period did not last more than

fifty years (Plut.

Quaest.

Graec.

50). At about the same time there was

further trouble in Euboea

itself,

in what was now Chalcis' private

property, the Lelantine plain, or at least in a plain in which the 'famed

warrior lords of Euboea' could practise their special skills against each

other. Whether or not the warrior lords actually came to blows on this

occasion is unknown - the poet Archilochus (below, p.

25

5-6) writes of

it in the future tense (fr. 3 West)

—

but, rather later, in the first part of

the sixth century, another poet, Theognis (891—4), names the plain and

uses the present. ' The wine-rich plain of Lelanton is being shorn bare.'

But who was shearing it and why? 'Cerinthus [a small city on the

north-east coast of Euboea] is lost.. .good men are in exile, bad run

the city. So may Zeus blast the whole clan of the Cypselidae.' The words

are clear but the sense is not. We have firm geography

—

Cerinthus and,

via the plain, Chalcis; we have the class struggle

—

'good' and 'bad';

1

IC XII. 9, 1273 -4; Hdt. v. 99; cf. A 21.

2

D 18.

3

D 6, )7-7i; D 14; D 63.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

252

EUBOEA AND THE ISLANDS

—

OUTLINE

OF

CLASSICAL

GATE

/ \^EARLY GRAVE

/

\

ENCLOSURE

CULT

ROOMS

42.

Eretria, the West Gate area in the sixth century B.C. (After

D

6,

figs. 8,

12.)

an international connexion

-

the Cypselids

of

Corinth. But even

if

we

accept an attractive suggestion that the Cypselids might have established

themselves

at

Cerinthus when

on

their way north

to

found Potidaea,

about 600 (and a beautiful emendation in a text of Plutarch, 'Cerinthus'

for ' Corinthus', which would then have these same Cypselids expelled

by

the

Spartans

in

55 6

or

thereabouts), the roles

of

Chalcis and class

remain dark, as dark as the reasons which later still led the Chalcidians

to join with

the

Thebans

in

luckless interference with Athens about

506.

4

This last fact serves to remind us how important Euboea always was

4

The suggestion about Cerinthus and the Corinthians

is

Wade-Gery's; E 162, 75-6.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE ISLANDS 253

as a link between Central Greece, including Attica, and the outside

world, Thrace, Chalcidice, the Black Sea; how closely, therefore, the

island was involved in the affairs of Central Greece, and Eretria

especially in the affairs, economic and therefore political, of Tanagra,

Oropus and north-east Attica. Pausanias (ix. 22.2) mentions an early

war between Tanagra and Eretria. The tangled story of the origins of

the Athenian tyrant-slayers, the Gephyraei, involves Tanagra and Eretria

as well as Aphidna where they finally settled.

5

Later instances abound.

Thus,

when an Eretrian suitor appears at the court of Cleisthenes of

Sicyon about 570 (below, p. 347), it was surely an Athenian link with

Cleisthenes, not a direct Cleisthenic interest in Eretria that brought him

there. A little later one Athenian connexion takes shape. Deeming it

prudent to flee from Athens in 556, Pisistratus found asylum in Thrace,

where Eretrian interests were strong, returned to Eretria and thence,

ten years later, mounted the expedition which won back his tyranny

(below, pp. 3981). Such things could not happen without Eretria's

official blessing and so, we may say, around the middle of the century

Eretrian politics reflected Eretrian economic ties with eastern Attica,

whence, of

course,

Pisistratus came. Indeed it is not impossible that the

representations of Athena and Theseus in the sculptures of the Apollo

temple later in the century owed something to this link with Attica, as

may the copious finds of fine Attic black-figure vases in Eretria.

6

But not too much can be gleaned for the long term. An Athenian

nobleman, Chaerion, who died at Eretria about 525, may himself have

been in flight from Pisistratus (though the assumption that he was is

too readily made).

7

More solidly, in 499, when Eretria chose to fight the

Persians in Ionia, she was also choosing to fight the Pisistratids, who

had gone over to the Persians. Economic interests survive personalities,

and the presence of men like the anti-Persian Callimachus in Aphidna

or the family connexions of anti-Persian Miltiades in the Brauron area

may have seemed more seductive that the absence of old friends with

the Persians. But this is thin ice.

Euboea was like a 'scabbard lying along the flank of Central Greece'.

In the dark it is hard to appreciate the existence of a scabbard unless

it rattles. Euboea did not rattle very often after 700.

II. THE

ISLANDS

Such glimpses of a political pattern in the Aegean as we can catch or

think we can catch in the late eighth century vanish with the coming

of the seventh. The apparent abandonment of the fortified settlement

5

Fj, no. 12267. *

H

'9. '5<>; H 66, 163-4.

7

F 5, no. 600.4.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

2 54 39^- EUBOEA AND THE ISLANDS

at Zagora on Andros, once an Eretrian dependency, at about the same

time as the desertion of Lefkandi, invites thought, but one example of

collaboration between Andrians and Chalcidians in the north would

scarcely allow that thought to take the shape of Eretrian collapse and

of a new Chalcidian presence in the northern Cyclades {CAH rn.i

2

,

768—9).

In any case the collaboration was short-lived.

We are left with the basic differences of geography and race described

in an earlier chapter and with the simple facts of island life. The islands

were isolated communities. The Aegean lay between them, and the

Aegean can be a powerful isolating factor even today. But the small

ships of Archaic Greece had to face not only Poseidon but pirates.

Thucydides

(1.

4) is romancing when he implies that the seas were

cleared in early days. The Greeks who sailed to Egypt about 660 were

pirates who found respectability; Polycrates of

Samos

was a pirate with

a state behind him; even the early campaigns of the Delian League in

the 470s were against pirates as well as Persians, and some have even

likened the Leaguers themselves to pirates. The best comment is a list

of those whom the little coastal city of Teos decided (about 470) to

include among its annual official curses: mass poisoners, dissidents,

revolutionaries, traitors -and pirates (M-L no. 30). The simple truth

is that the Aegean has been free of pirates only in those few periods

when there was some strong naval authority to keep it free - in the days

of Minos, perhaps; thereafter, in antiquity, only under Athens, under

Rhodes and under Rome (after Pompey).

Nevertheless the sea was also a unifying factor. Greeks sailed as

readily as they walked and, where interest led them, carried news and

ideas as well as goods. It is possible to imagine a completely isolated

island (not many ships will have called voluntarily on the Dolopian

pirates of Scyros

—

though according to Plutarch (Cim. 8) some were

foolish enough to do so), as it is possible to imagine a totally

uninhabited island, but by and large, and certainly along the main

sea-routes, these communities will have been as much aware of each

other and of the outside world as many cities of Thessaly and much

more than many cities of Arcadia. The question is how to hit a balance

between these two factors; in view of the lack of evidence an

unanswerable question. But, as this or that island drifts temporarily into

view, we must beware of thinking that it alone was enjoying the

experience, whatever it may have been. Only Paros produced an

Archilochus, but there was a Simonides of

Ceos,

a

different but no lesser

poet; only Thera's drought

is

recorded, but even meteorologists cannot

confine a drought to some 80 square kilometres; only Naxos is said to

have dominated other islands, but could Tenos ever ignore Andros?

Only Delos is unique

—

there was no anti-Pope.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008