Boardman J., Hammond N.G. L. The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 3, Part 3: The Expansion of the Greek World, Eighth to Sixth Centuries BC

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

INTERNAL DEVELOPMENTS AND RELATIONS 195

In the period that we have considered the western Greeks successfully

mastered their colonial environment. They were

not yet

seriously

threatened by outside powers, nor by the native population, and only

towards

the end by

their fellow Greeks. Their achievements went

beyond material success. Greeks from the west won many victories

at

Olympia, and towards the end

of

our period great schools of western

philosophy were growing up as a result of the arrival of refugees from

East Greece. Altogether they ranked among the leading cities

of

the

Greek world. The richest, if not the greatest, of these cities was Sybaris,

where the citizens pitied anyone who had

to go

abroad and 'prided

themselves

on

growing

old on the

bridges

of

their rivers'.

149

The

destruction

of

such

a

city may truly be called the end

of

an epoch.

149

Timaeus, FGrH 566 F

;O.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CHAPTER 39a

THE EASTERN GREEKS

J.

M.

COOK

The period dealt with here extends from about 700

B.C.

to

the time of

Polycrates' rule in the

5 30s

and 520s. In the wider historical perspective

it saw the rise of the Mermnad dynasty in Lydia, the aggression of Gyges

and

his

successors against

the

cities

of

the

Ionian coast

and

their

subjection

by

Croesus, and finally

the

conquest

of

Croesus' realm

by

Cyrus and the establishment of Persian rule over the eastern Greeks of

the Asiatic mainland.

It

does not reach

so far

as the organization and

extension

of

Persian rule

by

Darius.

As

regards

our

sources

of

information, archaeology gives occasional glimpses

of

habitations and

sanctuaries and casts light on trade movements; and the works

of

art

that have been discovered testify

to

a

taste and sense

of

form that

is

peculiarly East Greek. Inscriptions have little

to

offer; contemporary

ones that are relevant from

a

historical point

of

view can

be

counted

on

the

fingers

of

one hand. Among the literary sources Herodotus

is

pre-eminent. But his aim was

to

present the sequences

of

events that

preceded and led up to the conquests of the kingdoms of Asia and Egypt

by Cyrus and his successors and to the Persian Wars; and as far as Asia

Minor is concerned the rulers of Lydia and the Medes were more central

to his theme than the history

of

the East Greek cities, of which he tells

us many things but offers no continuous narrative. Later writers provide

scraps

of

information which

can not be

entirely neglected. But their

reliability

is

more questionable; and even

if

we gave credence

to

them

all,

the

difficulty

of

fitting them into their proper positions

is

often

insuperable.

I. THE LITERARY EVIDENCE

A great change occurred on the landward horizon of

the

eastern Greeks

about

the

beginning

of

the seventh century.

The

incursions

of

the

Cimmerians had been felt at the eastern end

of

Anatolia as early as 714

B.C.,

and

a

decade

or

two

later

the

Phrygian realm

of

Midas

was

overthrown when they captured its capital at Gordium (see CAHm.2

2

,

chs.

33d, 34a).

To

the West

of

this,

in

Lydia, the throne

at

Sardis was

usurped

by

Gyges, who founded

a

dynasty (the Mermnads) that was

196

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE LITERARY EVIDENCE 197

to be the dominant power in peninsular Asia Minor until the Persian

conquest.

1

Scholars now seem almost agreed

in

rejecting Herodotus'

dates for Gyges' reign (716-678

B.C.)

and bringing his accession down

to about 680,

at a

time when the collapse of Midas' kingdom had left

a power vacuum in Anatolia; his negotiations with Assyria (as early as

663) and subsequent alliance with Egypt show that he took determined

action

to

fill the vacuum and build up

a

powerful kingdom; and the

Greeks of the eastern Aegean thus found themselves confronted by

a

major power much closer

at

hand than the Phrygian had been and

commanding a number of different routes to the coast so that the Greek

cities could not plan

a

common defence.

Gyges was an aggressive neighbour.

It

is true that he is said to have

made offerings of silver and gold at Delphi and permitted the Milesians

to plant

a

colony

at

Abydus on the Dardanelles (above, p. 121); so

it

may be that he was conciliatory towards the Greeks

at

times when he

had other warlike commitments

on

hand (as those against the Cim-

merians). But

in

Herodotus (1. 14) we read that

he

attacked Smyrna

and Miletus and captured the town of Colophon. Another Cimmerian

onslaught proved fatal

to

Gyges

-

indeed the Greek cities too were

rocked by these and perhaps other intermittent incursions; and Gyges'

successors Ardys and Sadyattes in the second half of the seventh century

seem to have confined their Greek campaigns to southern Ionia, where

they captured Priene and raided Milesian territory. Alyattes inherited

Sadyattes' war against Miletus, which after five years he terminated with

a lasting treaty (according

to

Herodotus, 1. 21, he was tricked by the

tyrant Thrasybulus into believing that food supplies were plentiful

in

the city); and he destroyed Smyrna, which he seems to have captured

(probably about 600

B.C.

by means of a siege mound that enabled him

to surmount the massive city wall).

2

But when

he

advanced against

Clazomenae he

is

said

to

have suffered

a

serious reverse, presumably

at the hands of the Colophonian cavalry; and after that he seems to have

allowed the Greek cities to live in peace until his son Croesus resumed

the offensive against them. Before this, the Lydian attacks were not

aimed at gaining permanent possession of

the

Ionian sea-board, though

they effectively blocked any further Greek penetration

of

the interior.

But Croesus was

a

conqueror

at

heart, and Herodotus (1. 28) tells

us

that he reduced

to

subjection practically all the peoples of Asia as

far

as the River Halys, including of course the Carians, Dorians, Ionians,

and Aeolians

of the

coast lands. Sardis became increasingly

the

metropolis

of

the Greek East, with Croesus acting

not

only

as a

conqueror

but as

patron

of

the Greeks

of

Asia and

(in

moralizing

1

For the history

of

the Lydian kings see Hdt. i.

6ff.

2

D 24, 23-7; D 73,

88-91,

128-34.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

198

-

THE EASTERN GREEKS

are SB

m

Land over 1,000 metres

SCALE

0

I

150

200

JL

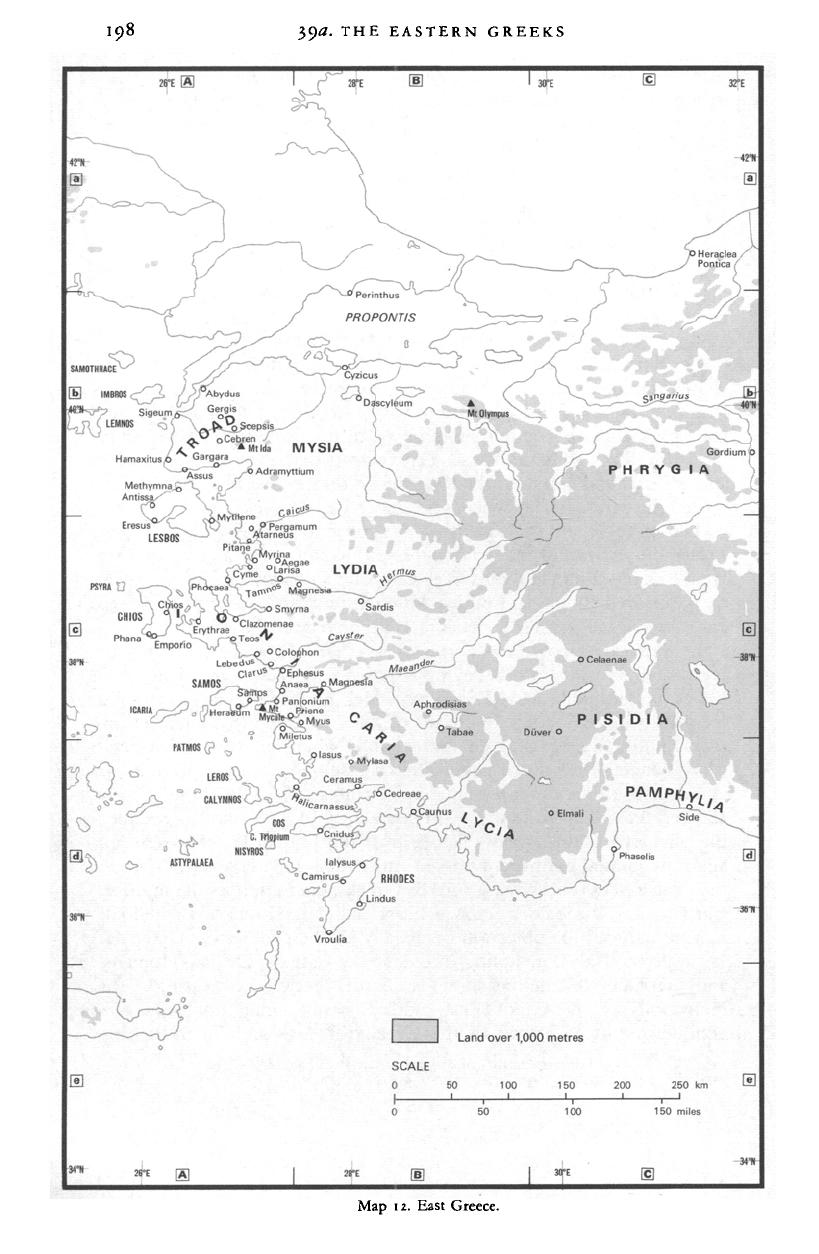

Map 12. East Greece.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE LITERARY EVIDENCE 199

anecdotes retailed by Herodotus,

i.

27—33;

vi. 125) graciously giving

interviews

to

Greek statesmen such

as

Bias

or

Pittacus, Solon, and

Alcmaeon. There was evidently intermarriage between Lydians and

eastern Greeks

in

the higher social stratum. The material culture

of

Sardis

in the

sixth-century levels shows much that

is

Greek

in

character

-

the more so because, unlike Phrygia, Lydia had not had

a

distinctive civilization of its own; and much of its art has a very Greek

appearance. As against this, the Ionians received new ideas and modes

in religion (e.g. the cults of Cybele and Bacchus), music, and perhaps

the organization and exploitation of wealth; in the sixth century Sappho

and the Colophonian thinker Xenophanes looked to Sardis as the source

of luxuries

—

the one nostalgically and the other with disapproval.

Croesus came to the throne some time about 560

B.C.

and had reigned

only fourteen years when he and his kingdom fell to Cyrus the Persian,

who asserted his claim

to

the whole

of

Croesus' realm

by

right

of

conquest. The peoples

of

Ionia, Caria, and Lycia resisted. But after

fighting which was especially stubborn in the south the cities were taken

by Cyrus' Median general Harpagus; and though

a

large part

of

the

population of Phocaea sailed away to join their kinsmen in the western

Mediterranean and a body from Teos went to settle at Abdera in Thrace,

the Greeks of

Asia

had fallen under Persian rule by about 540

B.C.

(Hdt.

1.

164—9).

O

n tne

mainland Miletus alone preserved the treaty rights that

its inaccessible situation had conferred on it. But the offshore islands

were not threatened

at

this time (the attribution of destruction of this

date on Samos to the Persians being quite conjectural); and since Cyrus

had no fleet the only constraint on the islanders before Darius' time was

their possession of agricultural land on the mainland opposite. This may

have prompted them

to a

nominal submission (Herodotus seems

to

contradict himself in the matter

of

their independence). But

it

seems

clear that with Miletus, Samos, Chios, Lesbos, and Rhodes effectively

free the eastern Greeks still enjoyed

a

fair degree

of

initiative. Sardis

of course had become the Persian administrative centre in the west, and

may perhaps not have continued

to

offer the same opportunities

for

commercial and cultural enrichment as

it

had done under Croesus.

The ancient sources agree in postulating the existence of kingship in

the Ionian cities at the time of the migrations. But it seems to have been

mostly short-lived, and the odd mentions of it surviving, as

in

Chios

and Aeolic Cyme, hardly bring us down beyond the end of the Dark

Age.

The most significant reminder is the family name Basilidae which

survived in places like Ephesus and Erythrae and carried much prestige

and some power as late as the seventh century; in Lesbos the founder's

family (the Penthilidae) seems likewise

to

have wielded power

in

the

seventh century.

In

Samos political power seems

to

have been

in

the

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

200

39

tf

-

THE

EASTERN GREEKS

hands of landowners (the

Geomoroi)

at the end of the seventh century

after the murder of a tyrant; a coup was effected on the return of an

expedition to Perinthus (the new Samian colony in the Propontis); but

it is not clear whether this was a struggle between classes or between

factions among the landowners, nor whether the landowners were at

this time so few as to constitute an oligarchy. For Miletus we have

stories indicating civil strife and atrocities, and the names given to the

political groups by later writers are suggestive on the one hand of

wealth, and on the other of artisanry or manual labour (and possibly

a suppressed native population), while the Parian arbitration that

followed in due course is said to have conferred the government on the

owners of well-kept land-holdings (thus setting up

a

moderate oligarchy

which will hardly have corresponded to the main aggregation of

wealth). We do not know when these troubles occurred; and if class

warfare is implied we do not know its alignments: whether for instance

a wealthy mercantile class was already in being and at variance with the

landowners, or whether a large body of urban poor was coming into

existence. And here again the troubles seem to have followed a tyranny

(that of Thoas and Damasenor).

3

There are two things that emerge from the literary (and in a lesser

degree epigraphical) evidence. One is that 'tyrants' were common in

East Greece from the later seventh century on, and that (as Aristotle

implies) they arose because of the great power vested for long periods

in the principal magistrate of a city. They need not be regarded as a

stage in a normal development from the rule of the few to some form

of democracy; in a time of rapid social and economic change the demand

for a strong executive could have been irresistible. The second point

concerns the tribes. The four old Ionic tribes, whatever their names may

have signified at the outset

{Geleontes

= radiant ones?, Aigikoreis =

herdsmen

~?,Argadeis

= handworkers or farmers

?,HopleUs

= warriorsor

the younger?), seem to have no connotation of status, and so far as our

limited knowledge carries they seem to be attested in early times in

southern and central Ionia at least (Miletus, Samos, Ephesus, Teos, but

not (it would seem) Phocaea, in whose colony of Lampsacus other

names were current); to these were added two additional names which

presumably represent accretions to the citizen bodies (Boreis and

Oinopes).

For Samos the evidence is derived from Perinthus which was

settled about 600

B.C.

;

but on the island itself the tribe names found

in later sources are quite different, and at Ephesus the old Ionian tribes

were down-graded to subdivisions of a single tribe

Ephesioi

and new

ones were created (partly at least with territorial names). At Ephesus

the reorganization occurred long before the time of Ephorus in the

fourth century, in Samos evidently after 600 B.C. On the assumption

3

The troubles at Samos and Miletus:

D

49, if.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE LITERARY EVIDENCE 2OI

that

at

Ephesus they date

to

the period

of

independence before the

Lydian and Persian conquest, scholars have recently attributed

the

changes to the tyrants in the first half of the sixth century; and in that

case we may see in them a great extension of citizenship to incorporate

Greek metics and immigrants, not to mention non-Greek natives,

in

the body politic on a partly territorial basis.

4

It is at this time also that

a reform

in

Chios, attested

by

the well-known 'constitution' stele,

established a new council containing fifty members from each tribe, thus

greatly increasing the power of the

demos.

5

At Miletus there seems

to

have been no corresponding reorganization of the old tribes (the old

names continued), and political strife seems to have been endemic there

through

the

sixth century. But

at

Ephesus

at

least,

and

perhaps

elsewhere in Ionia, the reforms may well have resulted in a broadening

of the basis of citizenship and spreading of political power at

a

time

when the great expansion

of

trade and manufacture had altered the

whole structure

of

an originally land-based society. The developing

social groups may have looked to tyrants as catalysts; and the changes

did not eliminate the need for tyrants because we hear the names of more

than half a dozen such who managed Ephesus

in

succession through

the greater part of the sixth century. The earlier ones

at

least had

to

excise opposition,

to

judge by stories that have come down through

later writers; and Herodotus (v. 92) lends some support to this when

he relates the Milesian tyrant Thrasybulus' advice

to

Periander

—

to

chop down any ear

of

corn that stood clear above its fellows; later

tyrants

of

Ephesus are said

to

have banished their citizen Hipponax

whose satirical verses give us our best indication of the polyglot society

that had come into being there after the middle of the sixth century.

The interest aroused among later Greek writers

by

the poems

of

Alcaeus permits some insight into the troubles that beset Mytilene in

the first half of

the

sixth century. After the overthrow of the Penthilidae

violence and intrigue were prevalent. A tyrant named Melanchrus did

not last long against a combination of leading families. But his successor

Myrsilus had the support

of

moderates like Pittacus, though not

of

Alcaeus and

his

friends who plotted unsuccessfully

to

unseat him.

Myrsilus died, and Alcaeus was exultant

—

but not for long, for Pittacus,

who had won fame by killing the Athenian leader Phrynon in the war

for the possession

of

Sigeum

at

the entry

to the

Hellespont, was

entrusted with supreme power by the people of Mytilene and Alcaeus

was once again in exile plotting a return. Pittacus ruled with restraint,

revising the laws rather than the constitution, and treating his opponents

with clemency when he had them in his power. He resigned his office

after ten years, leaving Mytilene on an even keel at last.

6

4

D 84; D 82.

5

D j6; D 74

' D75-

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

2O2

THE EASTERN GREEKS

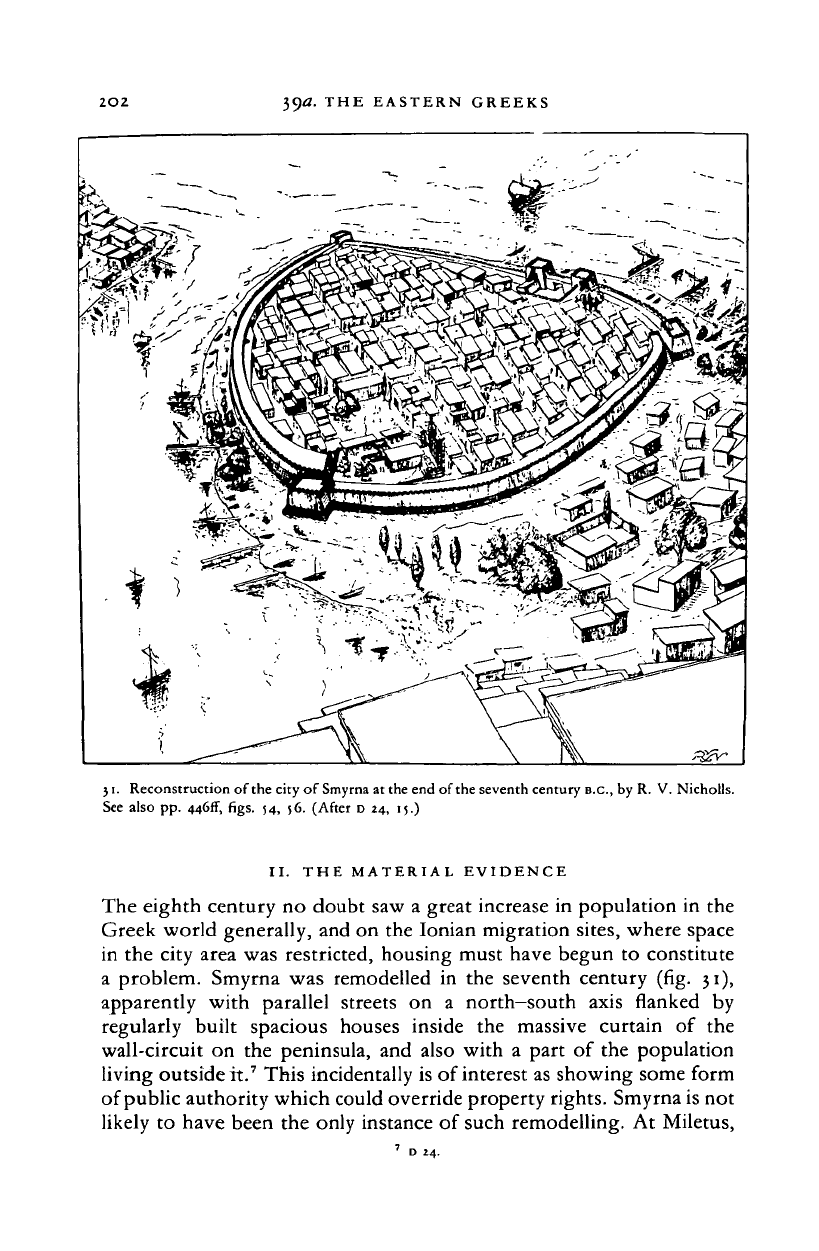

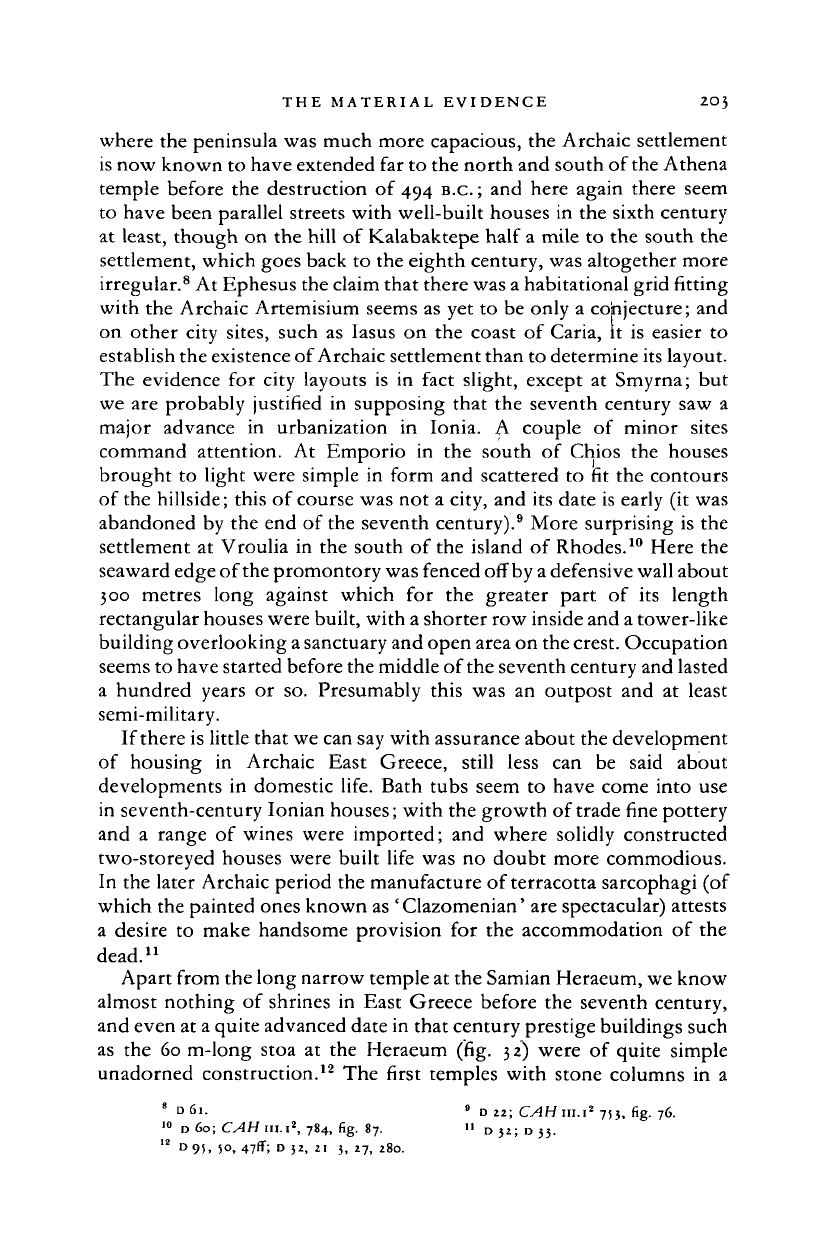

31.

Reconstruction of the city of Smyrna at the end of

the

seventh century B.C., by R. V. Nicholls.

See also pp.

446ff,

figs. 54, 56. (After D 24, 15.)

II.

THE MATERIAL EVIDENCE

The eighth century no doubt saw

a

great increase in population

in

the

Greek world generally, and on the Ionian migration sites, where space

in the city area was restricted, housing must have begun

to

constitute

a problem. Smyrna was remodelled

in the

seventh century (fig.

31),

apparently with parallel streets

on a

north—south axis flanked

by

regularly built spacious houses inside

the

massive curtain

of the

wall-circuit

on the

peninsula,

and

also with

a

part

of

the population

living outside it.

7

This incidentally is of interest as showing some form

of public authority which could override property rights. Smyrna is not

likely

to

have been the only instance

of

such remodelling.

At

Miletus,

'

D2

4

-

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE MATERIAL EVIDENCE 203

where the peninsula was much more capacious, the Archaic settlement

is now known to have extended far to the north and south of the Athena

temple before the destruction of 494 B.C.; and here again there seem

to have been parallel streets with well-built houses in the sixth century

at least, though on the hill of Kalabaktepe half a mile to the south the

settlement, which goes back to the eighth century, was altogether more

irregular.

8

At Ephesus the claim that there was a habitational grid fitting

with the Archaic Artemisium seems as yet to be only a conjecture; and

on other city sites, such as Iasus on the coast of Caria,

it

is easier to

establish the existence of Archaic settlement than to determine its layout.

The evidence for city layouts is in fact slight, except at Smyrna; but

we are probably justified in supposing that the seventh century saw a

major advance

in

urbanization

in

Ionia.

A

couple

of

minor sites

command attention. At Emporio

in

the south

of

Chios the houses

brought to light were simple in form and scattered to

fit

the contours

of the hillside; this of course was not a city, and its date is early (it was

abandoned by the end of the seventh century).

9

More surprising is the

settlement at Vroulia in the south of the island of Rhodes.

10

Here the

seaward edge of the promontory was fenced offby

a

defensive wall about

300 metres long against which

for

the greater part

of

its length

rectangular houses were built, with a shorter row inside and

a

tower-like

building overlooking

a

sanctuary and open area on the crest. Occupation

seems to have started before the middle of the seventh century and lasted

a hundred years or so. Presumably this was an outpost and at least

semi-military.

If there is little that we can say with assurance about the development

of housing

in

Archaic East Greece, still less can

be

said about

developments in domestic life. Bath tubs seem to have come into use

in seventh-century Ionian houses; with the growth of trade fine pottery

and

a

range of wines were imported; and where solidly constructed

two-storeyed houses were built life was no doubt more commodious.

In the later Archaic period the manufacture of terracotta sarcophagi (of

which the painted ones known as 'Clazomenian' are spectacular) attests

a desire to make handsome provision for the accommodation of the

dead.

11

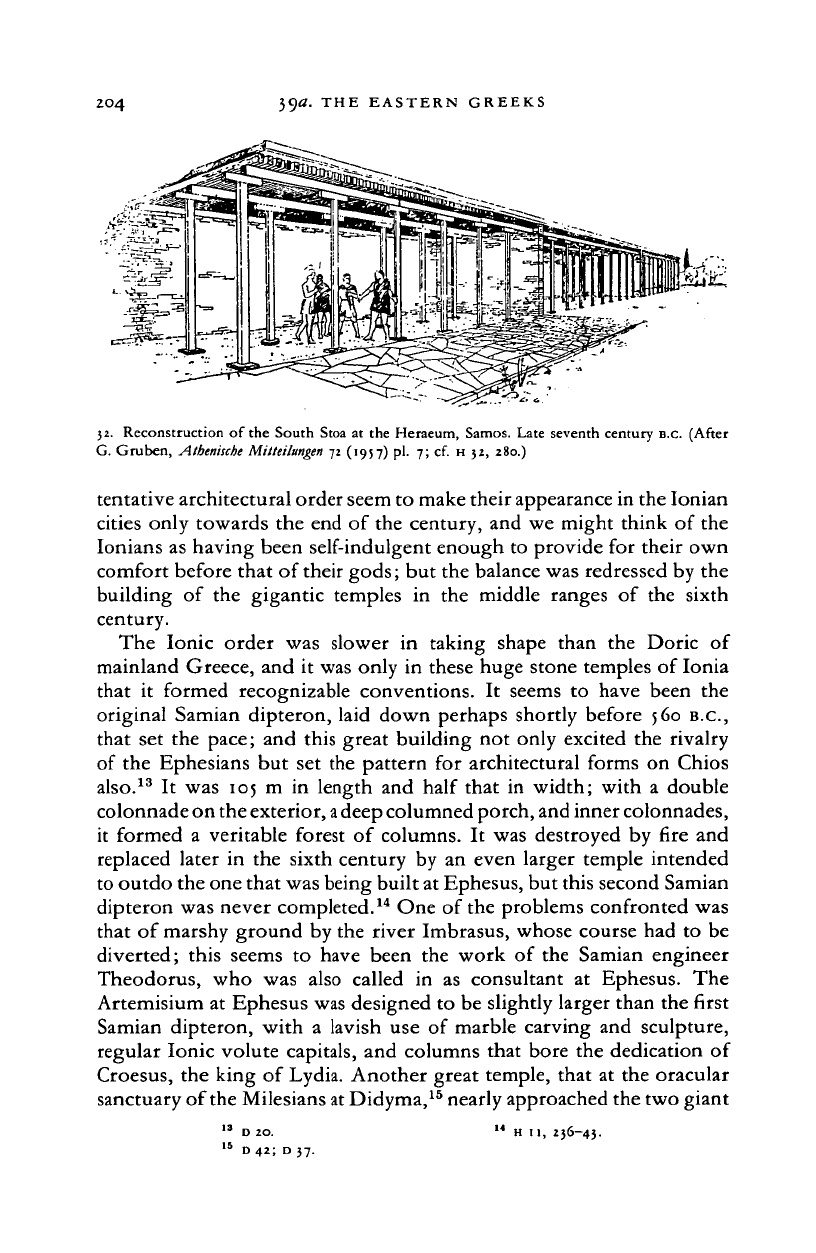

Apart from the long narrow temple at the Samian Heraeum, we know

almost nothing of shrines in East Greece before the seventh century,

and even at a quite advanced date in that century prestige buildings such

as the 60 m-long stoa at the Heraeum (fig. 32) were of quite simple

unadorned construction.

12

The first temples with stone columns in

a

' D6I.

»

D

22;

CAHiu.i

2

755,

fig.

76.

10

D 60;

CAH

in.i

2

, 784,

fig. 87. "

D52;D33.

12

D 9J, 50,

47ff;

D 52, 21 3, 27, 280.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

204

THE EASTERN GREEKS

32.

Reconstruction of the South Stoa at the Heraeum, Samos. Late seventh century B.C. (After

G. Gruben,

Athenische Mitteilungen

72 (1957) pi. 7; cf. H 32, 280.)

tentative architectural order seem to make their appearance in the Ionian

cities only towards the end of the century, and we might think of the

Ionians as having been self-indulgent enough to provide for their own

comfort before that of their gods; but the balance was redressed by the

building of the gigantic temples in the middle ranges of the sixth

century.

The Ionic order was slower in taking shape than the Doric of

mainland Greece, and it was only in these huge stone temples of Ionia

that it formed recognizable conventions. It seems to have been the

original Samian dipteron, laid down perhaps shortly before 560 B.C.,

that set the pace; and this great building not only excited the rivalry

of the Ephesians but set the pattern for architectural forms on Chios

also.

13

It was 105 m in length and half that in width; with a double

colonnade on the exterior,

a

deep columned porch, and inner colonnades,

it formed a veritable forest of columns. It was destroyed by fire and

replaced later in the sixth century by an even larger temple intended

to outdo the one that was being built at Ephesus, but this second Samian

dipteron was never completed.

14

One of the problems confronted was

that of marshy ground by the river Imbrasus, whose course had to be

diverted; this seems to have been the work of the Samian engineer

Theodorus, who was also called in as consultant at Ephesus. The

Artemisium at Ephesus was designed to be slightly larger than the first

Samian dipteron, with a lavish use of marble carving and sculpture,

regular Ionic volute capitals, and columns that bore the dedication of

Croesus, the king of Lydia. Another great temple, that at the oracular

sanctuary of the Milesians at Didyma,

15

nearly approached the two giant

D42;

D 37.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008