Balian E.V., L?v?que C., Segers H., Martens K. (Eds.) Freshwater Animal Diversity Assessment

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

the Greater Antilles and five in mainland Central

America) are semi-aquatic, representing four inde-

pendent derivations of this lifestyle. Several species

are capable of running on the water surface, but

lack specialized toe fringes. The tropidurid lizard

Uranoscodon superciliosus, likewise, can run on

water and feeds chiefly on invertebrates in the flotsam

at the water’s edge. Many species of gymnophthal-

mids of the genera Neusticurus and Potamites are

also semi-aquatic and are usually associated with

small streams. Several large teiid lizards of South

America are also typically restricted to water courses.

These include Crocodilurus amazonicus and two

species of Dracaena. Members of the latter genus

forage underwater, while walking on the bottom and

are predators on snails. Other Neotro pical lizards,

including the iguanid Iguana iguana and the teiid

Tupinambis teguixin, are often associated with fresh-

water habitats, but are not restrict ed to them.

Oriental region

This region contains the most species of semi-

aquatic lizards. The majority of species are in the

scincid genus Tropidophorus. Many of the species

for which data are available live alon g streambeds

and are the ecological equivalents of the Neotrop-

ical Neusticurus and Potamites. The Vietnamese

skink Sphenomorphus cryptotis is also restricted to

watercourses and has a laterally compressed tail.

The agamid Physignathus cocincinus, as well as all

species of Hydrosaurus are semi-aquatic and the

latter possess toe fringes like those of Basiliscus.

Table 2 Global distribution of freshwater lizard genera by biogeographic region

GN: genus Number PA NA NT AT OL AU PAC ANT World aquatic

Lizards

Agamidae 2 2 2

Corytophanidae 1 1

Gerrhosauridae 1 1

Gymnophthalmidae 2 2

Lanthanotidae 1 1

Polychrotidae 1 1

Scincidae 2 2 1 1 6

Teiidae 2 2

Tropiduridae 1 1

Varanidae 1 1 1 1 1

Xenosauridae 1 1

Total 0 0 7 4 7 4 2 0 19

Note that totals may be lower than the sum of all cells because some genera are shared between regions

PA: Palaearctic; NA: Nearctic; NT: Neotropical; AT: Afrotropical; OL: Oriental; AU: Australasian; PAC: Pacific Oceanic Islands;

ANT: Antarctic

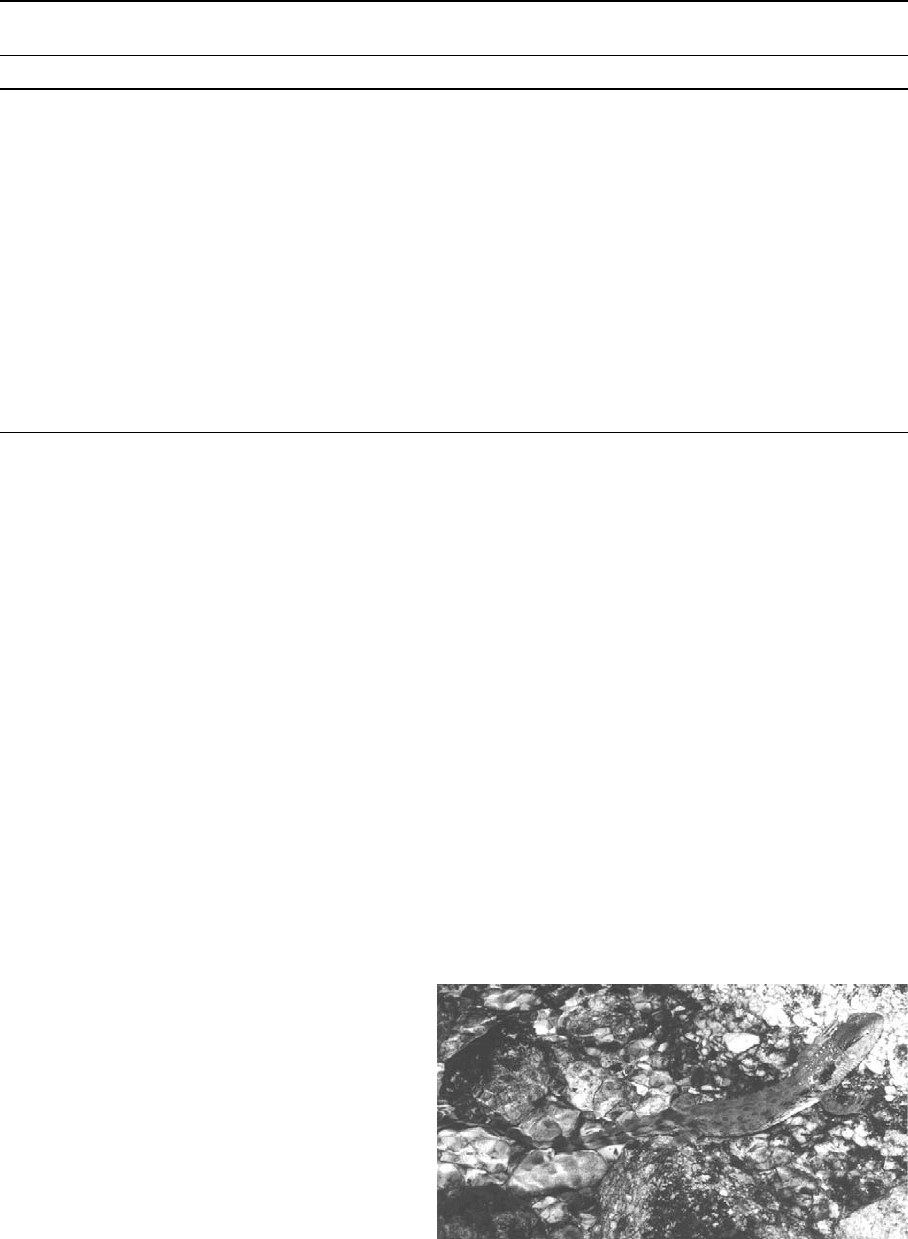

Fig. 1 Endangered

freshwater xenosaurid

lizard, Shinisaurus

crocodilurus, from Yen Tu

Nature Reserve, Quang

Ninh Province, Northeast

Vietnam with body

immersed in pool. Photo

courtesy of Le Khac Quyet/

FFI Vietnam

Hydrobiologia (2008) 595:581–586 583

123

One species, H. amboinensis, extends into the

Australasian region as far as New Guinea. Varanus

salvator is the largest aquatic lizard, reaching total

lengths of more than 3.0 m. It uses a broad range

of aquatic habitats and may be found in brackish or

even salt water, as well as freshwater. The Oriental

fauna also includes two highly distinctive and

phylogenetically isolated taxa, Shinisaurus and

Lanthanotus. Shinisaurus crocodilurus (Fig. 1) is

distributed in China and Vietnam and is amo ng the

most aquatic of lizards. The b iology of Lanthanotus

is poorly known, but its diet and limited natural

history observations indicate that it is both fossorial

and semi-aquatic.

Australasian region

Australasian freshwater lizards occur in the Agami-

dae, Scincidae, and Varanidae. The agamid

Physignathus lesueurii is at least semi-aquatic as

are four members of the Australian lygosomine skink

genus Eulamprus (E. quoyii, E. leuraensis,

E. kosciuskoi, E. tympanum). Three Australian spe-

cies of Varanus (V. mertensi, V. mitchelli,

V. semiremex) are typically semi-aquatic as are some

members of the Indo-Australian V. indicus complex

(V. caerulivirens, V. cerambonensis, V. jobiensis,

V. melinus; ecology unknown in some other recently

described species) although the degree of reliance on

freshwater varies significantly among these species.

One primarily Oriental species, V. salvator, extends

into Australasia in the region of Maluku, Indonesia.

Oceanic islands Pacific

Another member of the Varanus indicus complex,

V. juxtindicus of Rennell Island in the Solomons, is

also semi-aquatic and a single New Caledonian skink,

Lioscincus steindachneri, is strongly associated with

stream courses, particularly as juveniles.

Antarctica

No lizards of any kind occur in Antarctica.

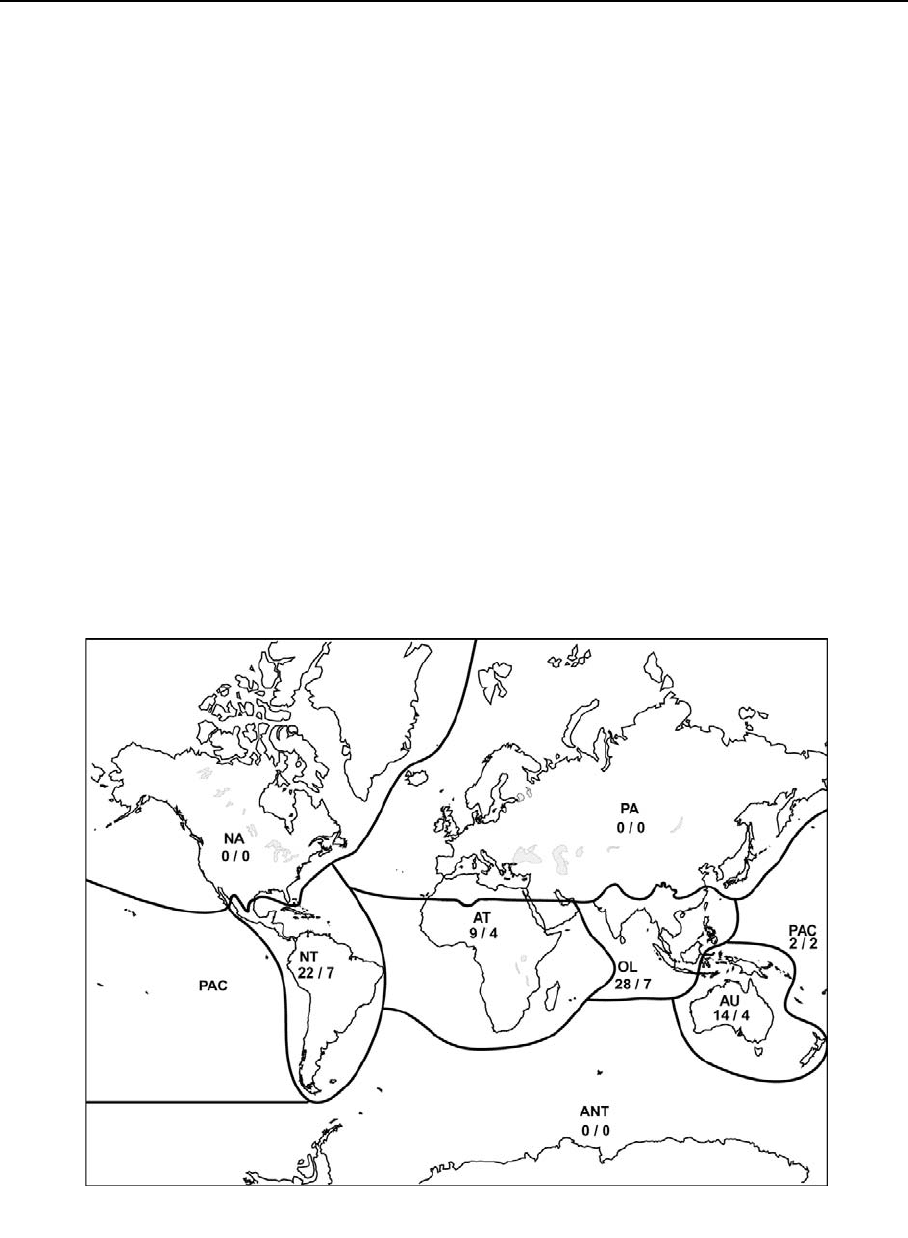

Fig. 2 Continental distribution of freshwater lizards. PA—Palaearctic; NA—Nearctic; NT—Neotropical; AT—Afrotropical ; OL—

Oriental; AU—Australasian; PAC—Pacific Oceanic Islands; ANT—Antarctic

584 Hydrobiologia (2008) 595:581–586

123

A total of 73 lizard species, or slightly less than

1.5% of all currently known taxa, is strongly

associated with freshwater habitats (see Table 1).

No lizard is known from the Antarctic Region and no

freshwater lizards have been recorded from either the

Nearctic or Palearctic regions. Aqua tic lizards are

most speciose in the tropics, particularly in associa-

tion with humid forest regions of Central and South

America, Southe ast Asia, and the Indo-Australian

Archipelago (Fig. 2, Tables 1, 2). Semi-aquatic hab-

its have evolved in many unrelated groups of lizards

and are typically not associated with highly special-

ized morphologies. However, most species that run

on the water surface are members of the Iguania, a

large clade of diurnal, visually oriented, ambush

predators, whereas those lizards that regularly swim

are members of a group of chemosensory active

foragers—the Autarchoglossa. The fundamental dif-

ferences between these two groups in activity,

foraging mode, and dominant sensory modalities

have u ndoubtedly contributed to their alternative

aquatic adaptations, as well as many other ecological

differences (Vitt et al. 2003).

Human related issues

Most lizards are too small to be consumed or otherwise

used commercially by humans. However, larger

lizards, including species of Varanus, Dracaena and

Crocodilurus are harvested for their skins and may be

regularly eaten by people. Harvesting for the skin trade

is especially high (>500,000/annum) for the two semi-

aquatic African Varanus species (de Buffre

´

nil 1993)

and for V. salvator (Luxmoore & Groombridge 1990).

Shinisaurus has been negatively impacted by defores-

tation and is becoming rare within its range (Le Khac

Quyet & Ziegler 2003). All aquatic species of Varanus,

Shinisaurus, Dracaena and Crocodilurus are CITES

Appendix II listed.

References

Avila-Pires, T. C. S., 1995. Lizards of Brazilian Amazonia

(Reptilia: Squamata). Zoologische Verhandelingen 299:

1–706.

Bedford, G. S. & K. A. Christian, 1996. Tail morphology

related to habitat of varanid lizards and some other

reptiles. Amphibia–Reptilia 17: 131–140.

Beebe, W., 1945. Field notes on the lizards of Kartabo, British

Guiana and Caripito, Venezuela. Part 3. Teiidae, Amphi-

sbaenidae and Scincidae. Zoologica (New York) 30: 7–31.

Blanc, C. P., 1967. Notes sur les Gerrhosaurinae de Mada-

gascar, I. - Observations sur Zonosaurus maximus,

Boulenger, 1896. Annales de l’Universite

´

de Madagascar

(Sciences) 5: 107–116.

Bo

¨

hme, W., A. Schmitz & T. Ziegler, 2000. A review of the

West African skink genus Cophoscincopus Mertens

(Reptilia: Scincidae: Lygosominae): resurrection of C.

simulans (Vaillant, 1884) and description of a new spe-

cies. Revue suisse de Zoologie 107: 777–791.

Daniels, C. B., 1987. Aspects of the aquatic feeding ecology of

the riparian skink Sphenomorphus quoyii. Australian

Journal of Zoology 35: 253–258.

Darevsky, I. S., N. L. Orlov & TC Ho, 2004. Two new lyg-

osomine skinks of the genus Sphenomorphus Fitzinger,

1843 (Sauria, Scincidae) from northern Vietnam. Russian

Journal of Herpetology 11: 111–120.

de Buffre

´

nil, V., 1993. Les Varans Africains (Varanus niloticus

et Varanus exanthematicus). Donne

´

es de Synthe

`

se sur leur

Biologie et leur Exploitation. Secre

´

tariat CITES, Gene

`

ve.

Doan, T. M. & T. A. Castoe, 2005. Phylogenetic taxonomy of

the Cercosaurini (Squamata: Gymnophthalmidae), with

new genera for species of Neusticurus and Proctoporus.

Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 143: 405–416.

Glaw, F. & M. Vences, 1994. A Fieldguide to the Amphibians

and Reptiles of Madagascar, second edition. M. Vences &

F. Glaw Verlags GbR, Ko

¨

ln.

Greer, A. E., 1989. The Biology & Evolution of Australian

Lizards. Surrey Beatty & Sons Pty. Ltd., Chipping

Norton.

Honda, M., H. Ota, R. W. Murphy & T. Hikida, 2006.

Phylogeny and biogeography of water skinks of the genus

Tropidophorus (Reptilia: Scincidae): A molecular

approach. Zoologica Scripta 35: 85–95.

Howland, J. M., L. J. Vitt & P. T. Lopez, 1990. Life of the

edge: The ecology and life history of the tropidurine ig-

uanid lizard Uranoscodon superciliosum. Canadian

Journal of Zoology 68: 1366–1373.

Le Khac Q. & T. Ziegler, 2003. First record of the Chinese

crocodile lizard from outside of China: Report on a pop-

ulation of Shinisaurus crocodilurus Ahl, 1930 from north-

eastern Vietnam. Hamadryad 27: 193–199.

Leal, M., A. K. Knox & J. B. Losos, 2002. Lack of conver-

gence in aquatic Anolis lizards. Evolution 56: 785–791.

Lee, M. S., 2005. Squamate phylogeny, taxon sampling, and

data congruence. Organisms, Diversity & Evolution 5:

25–45.

Luke, C., 1986. Convergent evolution of lizard toe fringes.

Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 27: 1–16.

Luxmoore, R. & B. Groombridge, 1990. Asian Monitor

Lizards: A Review of Distribution, Status, Exploitaion

and Trade in Four Selected Species. Secre

´

tariat CITES,

Lausanne.

Ma

¨

gdefrau,

H.,

1987. Zur Situation der Chinesischen Kro-

kodilschwanz-Ho

¨

ckerechse, Shinisaurus crocodilurus

Ahl, 1930. Herpetofauna 51: 6–11.

Pianka, E. R. & L. J. Vitt, 2003. Lizards, Windows to the

Evolution of Diversity. University of California Press,

Berkeley.

Hydrobiologia (2008) 595:581–586 585

123

Shine, R., 1986. Diets and abundances of aquatic and semi-

aquatic reptiles in the Alligator Rivers region. Supervising

Scientist for the Alligator Rivers Region Technical

Memorandum 16: 1–54.

Sprackland, G. B., 1972. A summary of observations of the

earless monitor, Lanthanotus borneensis. Sarawak

Museum Journal 20: 323–327.

Townsend, T. M., A. Larson, E. Louis & J. R. Macey, 2004.

Molecular phylogenetics of Squamata: the position of

snakes, amphisbaenians, and dibamids, and the root of the

squamate tree. Systematic Biology 53: 735–757.

Vitt, L. J. & T. C. S. Avila-Pires, 1998. Ecology of two

sympatric species of Neusticurus (Sauria: Gymno-

phthalmidae) in the western Amazon of Brazil. Copeia

1998: 570–582.

Vitt, L. J., E. R. Pianka, W. E. Cooper Jr. & K. Schwenk, 2003.

History and global ecology of squamate reptiles. The

American Naturalist 162: 44–60.

586 Hydrobiologia (2008) 595:581–586

123

FRESHWATER ANIMAL DIVERSITY ASSESSMENT

Global diversity of crocodiles (Crocodilia, Reptilia)

in freshwater

Samuel Martin

Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2007

Abstract Living crocodilians include the 24 species

of alligators, caimans, crocodiles and gharials. These

large semi-aquatic ambush predators are ubiquitous

in freshwater ecosystems throughout the world’s

tropics and warm temperate regions. Extant croco-

dilian diversity is low, but the group has a rich fossil

record in every continental deposit. Most populations

suffered from over-hunting and habitat loss during

the twentieth century and even though some species

remain critically endangered others are real success

stories in conservation biology and have become

important economic resources.

Keywords Crocodile Alligator

Gharial Archosauria

Introduction

The living crocodilians belong to the order Crocody-

lia which is now represented by three families: the

Crocodylidae, the Alligatoridae and the Gavialidae

(Brochu, 2003). The 24 species of the group are all-

amphibious and share morphological, anatomical,

and physiological features, which make them more

adapted to water than to land (Lang, 1976).

They all live in tropical and subtropical areas in

various aquatic habitats (forest streams, rivers,

marshes, swamp s, elbow lakes, etc.) and can be

considered as the largest fresh water dwellers. They

can occasionally adapt to salty waters (mangroves or

estuaries) (Dunson, 1982; Mazzotti & Dunson, 1984).

They are nocturnal carnivorous opportunistic preda-

tors, whose diet depends on their developmental

stage, species and potential prey diversity (Magnus-

son et al., 1987). All crocodilian species may be

considered as totally water dependent since they can

only mate in water. Crocodilians appear to be very

important for freshwater ecosystems as they main-

tain, during the dry season waterholes that are used as

reservoir for many arthropods, crustacean, fishes and

amphibians (Gans, 1989; Kushlan, 1974).

Species/generic diversity

With only 24 living species, the order Crocodylia is

the smallest taxonomic group of the class Reptilia.

The three families, Crocodylidae, Alligatoridae and

Gavialidae are quite homogeneous taxa as they

contain between two and four genera.

The highest level of species diversity is to be

found in the genus Crocodylus which gathers 13

species, whereas other genera only display one or two

species.

Guest editors: E. V. Balian, C. Le

´

ve

ˆ

que, H. Segers &

K. Martens

Freshwater Animal Diversity Assessment

S. Martin (&)

La Ferme aux Crocodiles, Pierrelatte 26700, France

e-mail: s.martin@lafermeauxcrocodiles.com

123

Hydrobiologia (2008) 595:587–591

DOI 10.1007/s10750-007-9030-4

The taxo nomic place of Tomistoma schlegelii is

also subject to debate among specialists. It used to be

placed with the subfamily Crocodylinae, whereas

other created the subfamilily Tomistominae. Based

on morphological features and on the latest DNA

studies, we chose to place them together with

Gavialis in the subfamily Gavialinae (Groombridge,

1987; Gatsby & Amato, 1992; Brochu, 2003).

(Tables 1, 2)

Phylogeny and historical processes

Crocodilians belong to the great group of archosaurs

which includes two extinct clades: the pterosaurs and

the dinosaurs (Blake, 1982). The history of the

crocodilians has been well reviewed by Buffetaud

(1982), Taplin (1984), Taplin & Grigg (1989) and

Brochu (2003). The very first crocodilians called

Protosuchians are from the early Jurassic, whereas

the Eusuchians (the modern crocodilians) appeared in

the upper Triassic around 220 Million years ago

under the form of terrestrial carnivores gathered in

the group of Pristichampsines. The eight surviving

genera of crocodilians are only a tiny rest of the past

diversity of the group which has been revealed by at

least 150 fossile genera (Broch u, 2003). The croco-

dilian diversity showed two peaks—one in the early

Eocene and the other one in the early Miocene

(Taplin, 1984; Markewick 1998). These fossils sug-

gest that crocodili omorphs were adapted to terrestrial,

sub-aquatic, and even to marine environment (cf.

Thalattosuchians). Until the end of the Tertiary, the

geographical distribution of the crocodilians was

much broader. The more restricted current distribu-

tion is due to the climatic deterioration, which

narrowed the tropical and subtropical zones (Marke-

wick, 1998).

Present distribution and main areas of endemicity

(Groombridge, 1987; Ross 1998)

Except the two Alligator species which are to some

extend more tolerant to colder temperatures, crocod-

ilians are distributed in inter-tropical wetl ands. As

shown in Table 3, most crocodilians are endemic of a

zoogeographical region. Only three species of the

genus Crocodylus (C. niloticus, C. porosus and C.

siamensis) and a gavialid (Gavialis gangeticus) are

found in two adjacent regions. The range of distri-

bution of crocodilians can be very variable in size.

Some species, such as the Nile crocodile (Crocody lus

niloticus) in Africa, the saltwater crocodile, (Croco-

dylus porosus) in the indopacific region or the

spectacled caiman ( Caiman crocodilus crocodilus)

in South America are widely represented at a

continental level, whereas most species are living in

more restricted areas. This is one of the reasons that

today half of the existing crocodilian species are

considered either as being endangered or threatened

according to the Red List criteria of the World

Conservation Union IUCN. The Chinese alligator

(Alligator sinensis), the Siamese crocodile ( Croco-

dylus siamensis), the Orinoco crocodile (Crocodylus

intermedius) and the Philippine crocodile (Crocody-

lus mindorensis) may be considered as the most

endangered crocodilians species. The first one is only

found in a few spots along the lower part of Yangtze

River with a remaining stronghold in the province of

Anhui in People’s Republic of China, the second one

is restricted to five Asian countries (Cambodia,

Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia and Laos) with

Table 1 Freshwater crocodilian species in the zoogeographical

regions

PA NA AT NT OL AU PAC ANT World

Alligatoridae 0 1 0 5 1 0 0 0 7

Crocodylidae 2 1 3 4 5 4 0 0 14

Gavialidae 1 0 0 0 2 0 0 0 2

Total 3 2 3 9 8 4 0 0

PA: Palaearctic, NA: Nearctic, NT: Neotropical, AT:

Afrotropical, OL: Oriental, AU: Australasian, PAC: Pacific

Oceanic Islands, ANT: Antarctic

Table 2 Freshwater crocodilian genera in the zoogeographical

regions

PA NA AT NT OL AU PAC ANT World

Alligatoridae 0 1 0 3 1 0 0 0 4

Crocodylidae 1 1 2 1 1 1 0 0 2

Gavialidae 1 0 0 0 2 0 0 0 2

Total 2 2 2 4 4 1 0 0 8

PA: Palaearctic, NA: Nearctic, NT: Neotropical, AT:

Afrotropical, OL: Oriental, AU: Australasian, PAC: Pacific

Oceanic Islands, ANT: Antarctic

588 Hydrobiologia (2008) 595:587–591

123

scattered extremely small populations, the third one is

restricted to the Orinoco water system of Venezuela

and Colombia only and the fourth one is endemic to

the archipelago of Philippines. The reasons for their

being endangered are due to human pressure on

habitat, but inversely linked to the adaptability to

habitat variations. For instance the Nile crocodile is

able to live in diverse aquatic environment s such as

streams, forest rivers, swamps, marshes, lagoons and

even small desert water holes like a few known small

populations lost in the Mauritanian Sahara (Pooley &

Gans, 1976; Shine et al., 2001). This species like

many other Crocodylidae and Alligatoridae are able

to walk long distances on dry land. When necessary

during long periods of drought they are able to

migrate to find new water spots. Other species such as

the mugger crocodile (Crocodylus palustris) will dig

burrows during the dry season to protect themselves

from the sun and wait in the shade the next raining

season (Rao, 1994). Other crocodilian species adapt

at burrowing are Alligator sinensis and Osteolaemus

tetraspis. According to IUCN criteria, out of 24

Table 3 Distribution of the 24 crocodilian species in the eight zoogeographical regions

Family Genus Species Sub species Distribution region Common name, IUCN red

list

Alligatoridae

(4 genera, 7 species)

Alligator A. mississippiensis Nearctic American alligator/LR

A. sinensis Oriental Chinese alligator/CR

Caiman C. crocodilus C.c. apaporiensis, Neotropical Spectacled caı

¨

man/LR

C. c. crocodilus,

C. c. fuscus

C. c. yacare

C. latirostris Neotropical Broad snouted caiman/LR

Melanosuchus M. niger Neotropical Black caiman/LR

Palaeosuchus P. palpebrosus Neotropical Cuvier’s smooth fronted

caiman/LR

P. trigonatus Neotropical Schneider’s smooth

fronted caiman/LR

Crocodylidae

(2 genera, 14

species)

Crocodylus C. acutus Nearctic; Neotropical American crocodile/Vu

C. cataphractus Afrotropical African slender snouted

crocodile/DD

C. intermedius Neotropical Orinoco crocodile/CR

C. johnsoni Australasia Australian freshwater

crocodile/LR

C. mindorensis Oriental Philippines crocodile/CR

C. moreletii Neotropical Morelet’s crocodile/LR

C. novaeguineae Australasia New guinea crocodile/LR

C. niloticus Palearctic, Afrotropical Nile crocodile/LR

C. palustris Palearctic, Oriental Marsh crocodile/LR

C. porosus Oriental, Australasia Estuarine crocodile/LR

C. raninus Oriental Borneo crocodile/DD

C. rhombifer Neotropical Cuban crocodile/EN

C. siamensis Oriental, Australasia Siamese crocodile/CR

Osteolaemus O. tetraspis O. t. tetraspis &

O. t. osborni

Afrotropical African dwarf crocodile/

Vu

Galvialidae

(2 genera,

2 species)

Gavialis G. gangeticus Palearctic, Oriental Gharial/EN

Tomistoma T. schlegelii Oriental False gharial/EN

Four species CR (Critically endangered), three species E (Endangered), 14 species LR (Low risks), two species DD (Data deficiency)

Hydrobiologia (2008) 595:587–591 589

123

crocodilian species, four are critically endangered,

three endangered and two species are considered as

vulnerable (IUCN red list of threatened species,

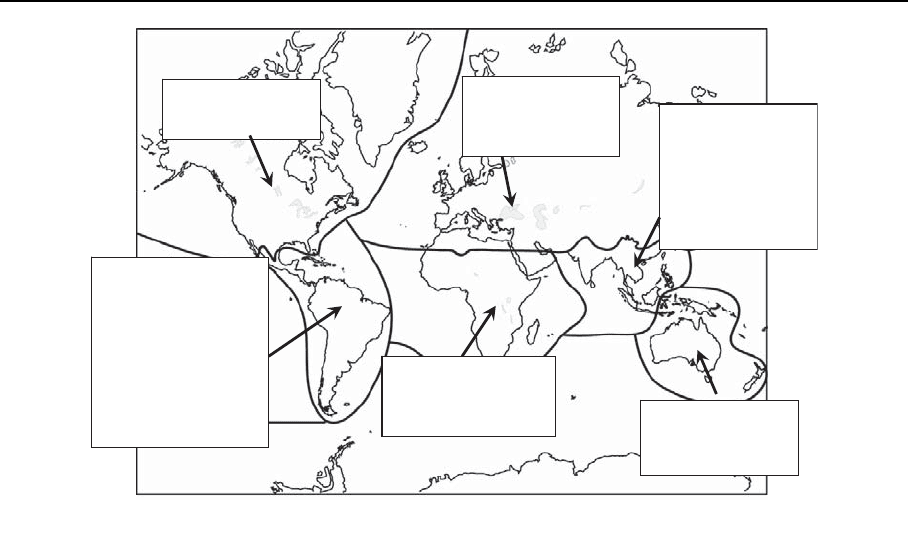

2004) (Fig. 1).

Human related issues

Humans and crocodilians have been interacting

since the dawn of civilization. Large crocodilians

are potentially dangerous to man as they can prey

on humans. Their populations have been depleted

until the mid 60’ies because the high prices paid for

their hides. In order to limit harvesting of wild

populations, farming and ranching programs have

been set up (Blake, 1982). Today several hundreds

of farms around the world are breeding and raising

crocodilians for leather and meat production (Braza-

itis et al., 1998). Despite these efforts, some wild

crocodilian populations are still depleting due to

competition with humans for habitat and food. Dam

construction on water streams has blocked seas onal

migration of aquatic species when their prey was

going down-stream during the rainy seas on and up-

stream when the water level lowers (Gans, 1989).

The draining of swamps for agricultural purposes

has increased drastically habitat fragmentation and

pollution. On a worldwide scale, the Crocodile

Specialist Group of the I.U.C.N. Species Survival

Commission coordinates crocodilian conservation

programmes. The most successful ones are based

on local community involvement combined with

education (Ross, 1998).

Complete bibliography can be found on: http://

utweb.ut.edu/faculty/mmeers/bcb/index.html

Reliable website: http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/cnhc/

csl.html

UNC/Species Survival Commission Crocodile

Specialist Group News letter http://www.flmnh.ufl.

edu/natsci/herpetology/ CROCS/CSGnewsletter.htm

References

Blake, D. K., 1982. Crocodile ranching in Zimbabwe. The

Zimbabwe Science News 26: 208–209.

Brazaitis, P., M. E. Watanabe & G. Amato, 1998. Trafic de

Caı

¨

mans. Pour la Science 247: 84–90.

Brochu, C. A., 2003. Phylogenetic approaches toward croco-

dilian history. Annual Revue of Earth Planet Science 31:

357–397.

Buffetaud, E., 1982. The evolution of crocodilians. American

Science 241:124–132.

:AN

sisneippississim rotagillA

sutucasulydocorC

:TA

sutcarhpatacsulydocorC

sucitolinsulydocorC

sipsartetsipsartetsumealoetsO

inrobsosipsartetsumealoetsO

:TN

sirtsoritalnamiaC

sisneiropapasulidocorcnamiaC

,sulidocorcsulidocorcnamiaC

sucsufsulidocorcnamiaC

eracaysulidocorcnamiaC

regin suhcusonaleM

susorbeplap suhcusoealaP

sutanogirt suhcusoealaP

sutucasulydocorC

suidemretni sulydocorC

iiteleromsulydocorC

refibmohr sulydocorC

:LO

sisnenis rotagillA

sisnerodnimsulydocorC

sirtsulapsulydocorC

susoropsulydocorC

suninarsulydocorC

sisnemaissulydocorC

sucitegnagsilaivaG

iilegelhcsamotsimoT

:AP

sucitolinsulydocorC

sirtsulapsulydocorC

sucitegnagsilaivaG

:UA

inotsnhojsulydocorC

eaeniugeavonsulydocorC

susoropsulydocorC

sisnemaissulydocorC

Fig. 1 Distribution of the 24 crocodilian species in the eight zoogeographical regions. PA: Palaearctic, NA: Nearctic, NT:

Neotropical, AT: Afrotropical, OL: Oriental, AU: Australasian, PAC: Pacific Oceanic Islands, ANT: Antarctic

590 Hydrobiologia (2008) 595:587–591

123

Dunson, W. A., 1982. Salinity relations of crocodiles in Florida

Bay. Copeia 2: 374–385.

Gans, C., 1989. Crocodilians in perspective! American Zool-

ogist 29: 1051–1054.

Gatsby, J. & G. D. Amato, 1992. Sequence similarity of 12S

ribosomal segment of mitochondrial DNAs of gharial and

false gharial. Copeia 1992: 241–244.

Groombridge, B., 1987. The distribution and status of world

crocodilians. In Webb, G. J. W., S. C. Manolis & P. J.

Whitehead (eds), Wildlife Management: Crocodiles and

Alligators. Chipping Norton, Australia, Surrey Betty and

Sons Printing in association with the Conservation Com-

mission of the Northern Territory, 9–21.

IUCN Red List of Threatened Specie, 2004. IUCN. Gland.

Switzerland.

Kushlan, A. J., 1974. Observations on the role of the Americain

alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) in the Southern

Florida Wetlands. Copeia 4: 993–996.

Lang, W. J., 1976. Amphibious behavior of Alligator missis-

sippiensis. Science 191: 575–577.

Magnusson, E. W., E. V. Da Silva & A. P. Lima, 1987. Diets of

Amazonian crocodilians. Journal of Herpetology 21: 85–

95.

Markewick, P. J., 1998. Crocodilian diversity in space and

time: the role of climate in paleoecology and its

implication for understanding K/T extinctions. Paleobi-

ology 24: 470–497.

Mazzotti, J. & W. A. Dunson, 1984. Adaptations of Crocodylus

acutus and Alligator for life in saline water. Comparative

Biochemistry and Physiology 79: 641–646.

Pooley, A. C. & C. Gans, 1976. The Nile crocodile. Scientific

American 234: 114–124.

Rao, R. J., 1994. Ecological studies of Indian crocodiles: an

overview. CSG Proceedings, Pattaya, Thailand, 2–6 May

1994. Crocodile Specialist Group, Vol. 1, 259–273.

Ross, J. P. 1998. Crocodiles-Status, Survey and Conservation

Action Plan. International Union for Nature Conservation

Switzerland.

Shine, T., W. Bo

¨

hme, H. Nickel, D. F. Thies & T. Wilms,

2001. Rediscovery of relict populations of the Nile croc-

odile Crocodylus niloticus in South-Eastern Mauritania,

with observations on their natural history. Oryx 35: 260–

262.

Taplin, L., 1984. Evolution and zoogeography of crocodilians:

a new look at an ancient order. In Archer, M. & G.

Clayton (eds), Vertebrate Evolution and Zoogeography in

Australasia. Hesperian Press, Perth, 361–370.

Taplin, L. E. & G. C. Grigg, 1989. Historical zoogeography of

the eusuchian crocodilians: a physiological perspective.

American Zoology 29: 885–901.

Hydrobiologia (2008) 595:587–591 591

123

FRESHWATER ANIMAL DIVERSITY ASSESSMENT

Global diversity of turtles (Chelonii; Reptilia) in freshwater

Roger Bour

Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2007

Abstract The turtles are an evolutionary ancient

group of tetrapod vertebrates, and their present-day

distribution and diversity reflects the long and complex

history of the taxon. Today, about 250 of the total of 320

species recognized are freshwater turtles; most of these

inhabit tropical and subtropical zones. Diversity hotspots

occur in Southeast North America, regarding Emydidae,

and in the Indo-Malayan region, mostly Geoemydidae

and Trionychidae. Chelidae are predominantly Neotrop-

ical and Australasian, while Pelomedusidae are African.

The majority of genus- and species-level taxa are

regional or even local endemics. A majority of freshwa-

ter turtles are threatened in varying degrees, mostly by

habitat modification and collection.

Keywords Biodiversity Zoogeography

Chelonii Review

Introduction

Turtles or Chelonians (order Chelonii, class Reptilia)

are very ancient tetrapod vertebrates, their first

members being known from Keuper (Triassic) deposits

of ca. 230 M years old. The extant families have a relict

distribution pattern that reflects their long evolutionary

history. Morpho-functional analysis of their fossil

remains, especially their limbs, reveals that the oldest

known Chelonians most likely inhabited swamps or

marshlands, and their present relatives are mostly

freshwater species.

Soon after its emergence (Triassic–Jurassic), the

order split into two groups diagnosed by several

anatomical features, amongst which are the articula-

tion of the cervical vertebrae and bending of the neck.

These groups, namely Pleurodira (neck bending in a

horizontal plane: ‘‘side neck’’) and Cryptodira (neck

bending in a vertical plane, and neck more or less

retractable inside the shell: ‘‘hidden neck’’), are still

present today, although they have different and

unequal areas of occurrence and species richness.

Cryptodira includes freshwater turtles in addition to

marine turtles and terrestrial tortoises, while all

Pleurodira species are more or less completely fresh-

water dependant (Fig. 1).

Reliance of turtles on freshwater is quite variable,

depending on the species, and also on the age for

some species. Roughly, the typical habitat may vary

from large rivers and lakes, sometimes estuaries, to

swamps, marshes, bogs, occasionally brackish waters,

and some species are nearly as terrestrial as true land

tortoises, which, themselves, include a few species

that require a very damp environment. ‘‘Terrestrial’’

freshwater turtles are encountered in both large

Guest editors: E. V. Balian, C. Le

´

ve

ˆ

que, H. Segers &

K. Martens

Freshwater Animal Diversity Assessment

R. Bour (&)

Reptiles et Amphibiens, Syste

´

matique et Evolution,

Muse

´

um national d’Histoire naturelle, 25 rue Cuvier,

Paris 75231, France

e-mail: bour@mnhn.fr

123

Hydrobiologia (2008) 595:593–598

DOI 10.1007/s10750-007-9244-5