Balian E.V., L?v?que C., Segers H., Martens K. (Eds.) Freshwater Animal Diversity Assessment

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

FRESHWATER ANIMAL DIVERSITY ASSESSMENT

Global diversity of cumaceans & tanaidaceans (Crustacea:

Cumacea & Tanaidacea) in freshwater

D. Jaume Æ G. A. Boxshall

Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2007

Abstract Cumacea and Tanaidacea are marginal

groups in continental waters. Although many eury-

haline species from both groups are found in estuaries

and coastal lagoons, most occur only temporarily in

non-marine habitats, appearing unable to form stable

populations there. A total of 21 genuinely non-mar ine

cumaceans are known, mostly concentrated in the

Ponto-Caspian region, and only four tanaids have

been reported from non-marine environments. Most

non-marine cumaceans (19 species) belong in the

Pseudocumatidae and appear restricted to the Caspian

Sea (with salinity up to 13 %) and its peripheral

fluvial basins, including the northern, lower salinity

zones of the Black Sea (Sea of Azov). There are nine

Ponto-Caspian genera, all endemic to the region.

Only two other taxa (in the family Nannastaci dae)

occur in areas free of any marine–water influence, in

river basins in North and South America. Both seem

able to survive in waters of raised salinity of the

lower reaches of these fluvial systems; but neither has

been recorded in full salinity marine environments.

The only non-marine tanaidacean thus far known

lives in a slightly brackish inland spring in Northern

Australia. The genus includes a second species, from

a brackish-water lake at the Bismar ck Archipelago,

tentatively included here as non-marine also. Two

additional species of tanaidaceans have been reported

from non-marine habitats but both also occur in the

sea.

Keywords Freshwater Global assessment

Species richness Peracarida Crustacea

Introduction

Comprising about 1,300 and 900 marine species,

respectively, the Cumacea and Tanaidacea are only

marginal groups in continental waters. Altho ugh

many euryhaline species in both taxa are found in

estuaries and coastal lagoons, most occur only

temporarily in non-marine habitats, appearing unable

to form stable populations there. Only 21 genuinely

non-marine cumaceans are known, most of which

occur in the Ponto-Caspian region, whereas just four

tanaids have been reported in non-marine habitats.

Both groups are orders of peracarid crustaceans that

are mainly adapted to a fossorial life-style in non-

consolidated marine sediments, especially in deep

Guest editors: E. V. Balian, C. Le

´

ve

ˆ

que, H. Segers &

K. Martens

Freshwater Animal Diversity Assessment

D. Jaume (&)

IMEDEA (CSIC-UIB), Instituto Mediterra

´

neo de Estudios

Avanzados, C/ Miquel Marque

`

s 21, Esporles, Illes Balears

07190, Spain

e-mail: d.jaume@uib.es

G. A. Boxshall

Department of Zoology, The Natural History Museum,

Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UK

e-mail: g.boxshall@nhm.ac.uk

123

Hydrobiologia (2008) 595:225–230

DOI 10.1007/s10750-007-9018-0

waters, although they can appear regularly in night-

time plankton hauls in shallow waters.

The characteristic body form of a cumacean

consists of a large, variably inflated cephalothorax

incorporating the first 3 (of 8) thoracic somites, plus

an elongate, narrow abdomen terminating in a pair of

long and slender uropod s. The cephalothorax displays

a pair of frontal extensions, the pseudorostral lobes,

which converge medially in most instances, whereas

its lateral portions act as paired branchial chambers

accommodating the respiratory epipodites of the first

maxillipeds (see below). All thoracopods except the

first, second and eighth are primitively biramous. The

first pair (=first maxillipeds) is characteristic, pos-

sessing a respiratory coxal epipodite provided with

digitiform extensions in addition to a narrow frontal

extension, which together with the corresponding

cephalothoracic pseudorostral lobe, forms a branchial

siphon (exhalant canal) for the corresponding bran-

chial chamber. The abdomen comprises six free

pleomeres and a free telson, although in some

families the latter is incorporated into the sixth

pleomere forming a pleotelson. Apart from the

uropods on the last pleomere, there are up to five

pairs of pleopods in males, but a maximum of only

one pair in females. Reduction in number of pairs of

pleopods is common. All these limbs are originally

biramous, with a 2-segmented exopod and a uniseg-

mented endopod; the endopod of the uropod can be

up to 3-articulate. Cumaceans are primarily deposit

feeders, although some are apparently predators of

foraminifers and other crustaceans. Most live half-

buried in soft sediments.

General morphological characteristics for the

order Tanaidacea include: a small cephalothorax

incorporating the first two thoracic somites, six free

thoracic somites, five abdominal somites bearing

pleopods, and a pleotelson with a pair of uropods. All

thoracopods except the third (=first pereiopod) of

most apseudomorphs, and some other pereiopods of

the manca stages of the genus Kalliapseudes, are

uniramous. The maxillipeds (=first thoracopods)

possess a respiratory coxal epipodite, which is

concealed under the lateral margin of the cephalo-

thorax (branchial cavity). The second pair of

thoracopods is prehensile, displaying a chelate distal

portion (‘‘chelipeds’’). The pleopods and uropods are

basically biramous with 2-segmented exopods and

unisegmented endopods, although both rami of the

uropods can be multi-articulate, due to the display of

cuticular annulations. Tanaidaceans are primarily

tube or tunnel dwellers, and are generally considered

to be deposit feeders.

Species diversity, distribution and historical

processes

Non-marine cumaceans belong to two of the eight

recognised families: Pseudocumatidae Sars and Nan-

nastacidae Bate. Most non-marine species (19) are

pseudocumatids and their distribution is focused

around the Caspian Sea (maximum salinity 13%)

and its peripheral fluvial basins, including the north-

ern, lower salinity zones of the Black Sea (Sea of

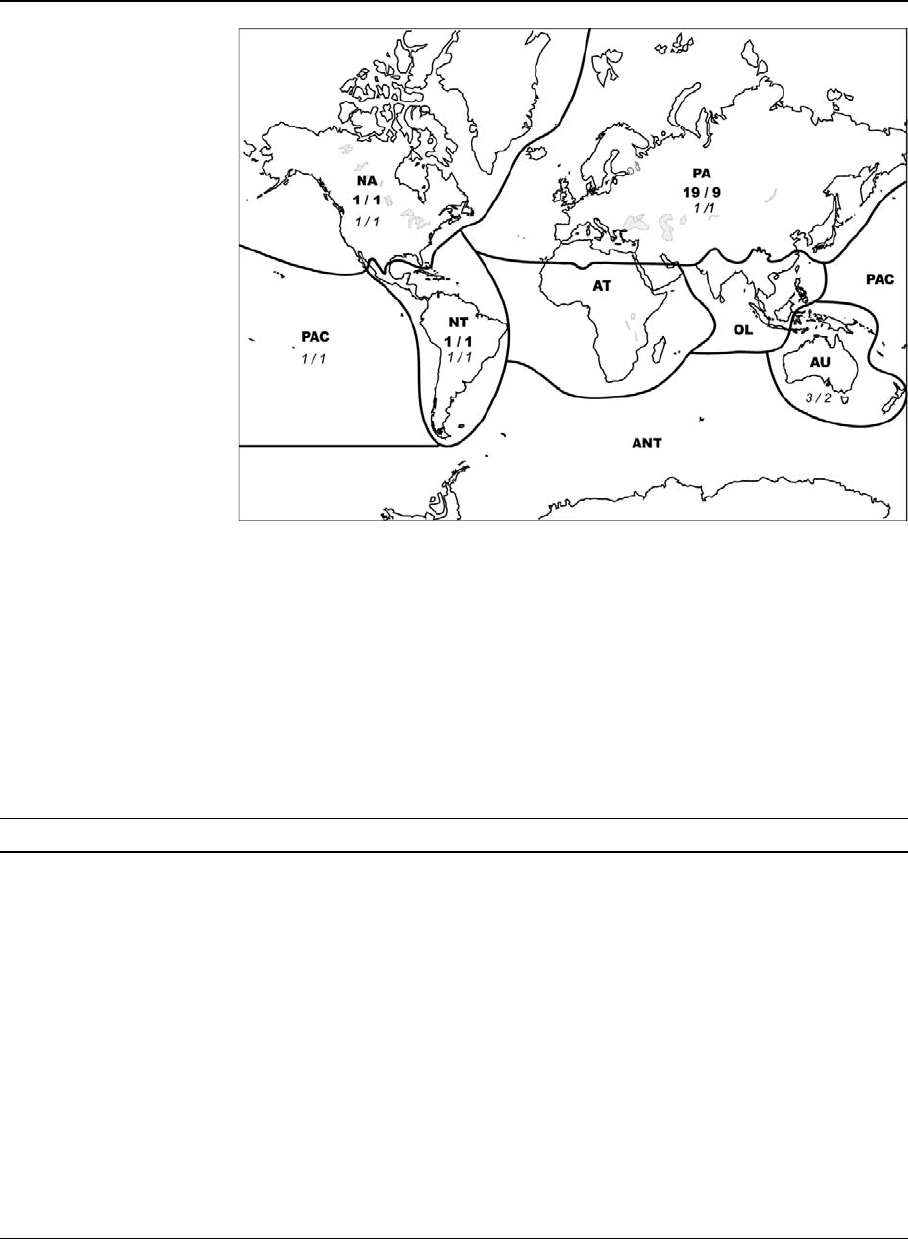

Azov) (see Tables 1 and 3; Fig. 1). They represent

nine genera, all endemic to the region, although the

taxonomic status of some genera is equivocal (e.g.

Charsarocuma; see comments by Sars (1914: 32) on

its presumed synonymy with Schizoramphus ) and

their validity should be tested. The natural distribu-

tion of these taxa within the Ponto-Caspian region is

difficult to ascertain since dispersal via artificial

canals and reservoirs, by shipping, or even by

deliberate introduction as fish food, may have had a

profound effect (see Ba

˘

cescu & Petrescu, 1999, and

references therein). Stenocuma graciloides has

recently been reported from the Gulf o f Finland

(Baltic Sea), where it may have been transported by

ships passing through the Volga-Baltic waterway

from its North Caspian home (Antsulevich, 2005).

The presumed deliberate introduction of Stenocuma

gracilis, Pterocuma pectinata and Schizorhamphus

scabriusculus into the Aral sea, to serve as fish food

(Karpevitch, 1960; quoted in Ba

˘

cescu & Petrescu,

1999), seems not to have succe eded (Nikolay Aladin,

pers. comm.). Apart from these Caspian pseudocu-

matids, only two other taxa (from the Nannastacidae)

occur in areas free of any marine-water influence, in

river basins in North and South America. Both seem

able to survive in waters of raised salinity of the

lower reaches of these fluvial systems (see Tables 1

and 3; Fig. 1), but neither has been recorded in full

salinity marine environments. These two monotypic

genera are endemic to their respective river basins.

Sars (1914) considered that the Caspian Cumacea

were derived from a single ancestral form originating

from the Mediterranean, probably belonging to the

226 Hydrobiologia (2008) 595:225–230

123

marine genus Pseudocuma Sars, 1865, which

includes three Mediterranean species, one of which

is also present in the Black Sea. The Caspian genus

Stenocuma is considered to be a subgenus of

Pseudocuma by some authors (Ba

˘

cescu, 1992).

Dumont (2000: 186) believed that Caspian cuma-

ceans were derived from ancestral forms that lived in

estuaries and tidal zones of rivers that discharged into

Table 1 Global diversity of non-marine Cumacea (distribution of Ponto-Caspian taxa after Ba

˘

cescu (1992) and Antsulevich (2005))

Order Cumacea Distribution

Family Pseudocumatidae G. O. Sars, 1878

Genus Carinocuma Mordukhai-

Boltovskoi & Romanova, 1973

C. birsteini Mordukhai-Boltovskoi &

Romanova, 1973

Caspian Sea

Genus Caspiocuma G. O. Sars, 1900

C. campylaspoides (G. O. Sars, 1897) Caspian Sea; Volga, Don, Bug and Dniestr river basins

Genus Charsarocuma Derzhavin, 1912

C. knipowitschi Derzhavin, 1912 Caspian Sea; pre-delta region of Volga

Genus Hyrcanocuma Derzhavin, 1912

H. sarsi Derzhavin, 1912 Caspian Sea

Genus Stenocuma G. O. Sars, 1900

S. gracilis (G. O. Sars, 1894) Caspian Sea; Volga

S. graciloides (G. O. Sars, 1894) Caspian Sea; Estuaries of Volga, Don, Dniestr and Danube; Black Sea (Azov);

Gulf of Finland (Baltic Sea)

S. tenuicauda (G. O. Sars, 1894) Caspian Sea; Volga

S. diastyloides (G. O. Sars, 1897) Caspian Sea

S. cercarioides G. O. Sars, 1894 Caspian Sea; Volga, Don, Bug and Dniestr river basins; Black Sea

S. laevis (G. O. Sars, 1914) Caspian Sea

Genus Pterocuma G. O. Sars, 1900

P. pectinata (Sowinski, 1893) Caspian Sea; Volga, Danube and Dniestr river basins; Black Sea

P. rostratum (G. O. Sars, 1894) Caspian Sea; Volga; estuaries of Dniepr, Bug and Danube; Black Sea

P. sowinskyi (G. O. Sars, 1894) Caspian; Volga; delta of Don; Black Sea

P. grandis G. O. Sars, 1914 Caspian Sea

Genus Schizorhamphus Ba

˘

cescu, 1992

S. bilamellatus (G. O. Sars, 1894) Caspian Sea; Volga

S. eudorelloides (G. O. Sars, 1894) Caspian Sea (up to 264 m depth); river mouths of Danube, Dniestr and Prut;

Black Sea

S. scabriusculus (G. O. Sars, 1894) Caspian Sea; Danube, Dniestr, Bug and Dniepr rivers

Genus Strauchia Czerniavsky, 1868

S. taurica Czerniavsky, 1868 Caspian Sea

Genus Volgocuma Derzhavin, 1912

V. telmatophora Derzhavin, 1912 Caspian Sea; Volga; Black Sea

Family Nannastacidae Bate, 1866

Genus Almyracuma Jones & Burbanck,

1959

A. proximoculi Jones & Burbanck, 1959 Intertidal freshwater springs at Cape Cod, and limnetic zone of Lower Hudson river

(latter 1–30%; Simpson et al., 1985), NE U.S.A.

Genus Claudicuma Roccatagliata, 1981

C. platense Roccatagliata, 1981 Rı

´

o de la Plata (Argentina), from Buenos Aires (0.5%) to Punta del Indio (1.8–7.0%)

(Roccatagliata, 1991)

Hydrobiologia (2008) 595:225–230 227

123

the (proto-) Mediterranean before the closure of the

Sarmatian Basin, a vanished Miocene brackish lake

that covered the entire Ponto-Caspian region from

14.5 to 8.3 Myr ago. Their osmoregulatory abilities

would have preadapted them to life in the brackish

Sarmatian lake.

The only truely non-marine tanaidacean known is

Pseudohalmyrapseude s aquadulcis (Parapseudidae)

which lives in a slightly brackish inland spring in

Northern Australia (see Tables 2 and 3; Fig. 1; Larsen

& Hansknecht, 2004). The genus includes a second

species, P. mussauensis, from a brackish-water lake

in the Bismarck Archipelago; this species is tenta-

tively included here as non-marine, since the genus

has not been recorded yet in fully marine environ-

ments, and Shiino (1965) was rather vague in his

description of the salinity regime of the lake where the

species was discovered (see Tables 2 and 3; Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Total species and

genus numbers of Cumacea

(Bold) and Tanaidacea

(italics) per zoogeographic

regions (Species number/

Genus number). PA:

Palaearctic, NA: Nearctic,

NT: Neotropical, AT:

Afrotropical, OL: Oriental,

AU: Australasian, PAC:

Pacific Oceanic Islands,

ANT: Antarctic

Table 2 Global diversity of non-marine Tanaidacea

Order Tanaidacea Distribution

Family Parapseudidae Gutu, 1981

Genus Pseudohalmyrapseudes Larsen

& Hansknecht, 2004

P. aquadulcis Larsen & Hansknecht, 2004 ‘‘Freshwater spring’’ (but 1.93% in salinity), Australian Northern Territory

P. mussauensis (Shiino, 1965) ‘‘Brackish lake’’, Bismarck Archipelago (Papua New Guinea)

Family Tanaidae Dana, 1849

Genus Sinelobus Sieg, 1980

S. stanfordi (Richardson, 1901) Marine, plus freshwater, hypohaline and hypersaline inland waters of Galapagos,

Japan, Hong Kong, New Zealand, Australia, Argentina, Kurile Islands,

West Indies, Florida and Brazil (see Larsen & Hansknecht, 2004, and

references therein)

Family Anarthruridae Lang, 1971

Genus Paraleptognathia Kudinova-Pasternak,

1981

P. longiremis (Lilljeborg, 1864) Deep sea plus… Lake Baikal! (Kudinova-Pasternak, 1972) Record requiring

confirmation

228 Hydrobiologia (2008) 595:225–230

123

Larsen & Hansknecht (2004) suggest that Pseudohal-

myrapseudes occupies an intermediate position

between the euryhaline genus Halmyrapseudes Ba

˘

ce-

scu & Gutu, 1972 and Longiflagrum Gutu, 1995,

although no phylogenetic analysis was performed to

support this sugges tion. The Australian species is

inferred to have reached the spring it inhabits via the

groundwater system, although the possibility of an

upstream migration from the ocean cannot be ruled

out.

Two other species of tanaidaceans have been

reported from non-mar ine habitats, but both occur

also in marine environments. Sinelobus stanfordi

(Tanaidae), a widely distributed euryharine taxo n, has

been reported repeatedly from geographically scat-

tered freshwater, hypohaline or hypersaline lakes

(Tables 2 and 3; Fig. 1). In addition, there is a

doubtful record of the deep-sea trench Paraleptogna-

thia longiremis (Anarthruridae) from Lake Baikal

(Kudinova-Pasternak, 1972; Tables 2 and 3; Fig. 1).

This record requires confirmation and, as Larsen &

Hansknecht (2004) point out, the conspecificity of the

non-marine populations of these two taxa to their

corresponding marine forms should be confirmed,

suggesting that the current diversity of non-marine

tanaidacean species is underestimated.

Acknowledgement This is a contribution to Spanish MEC

project CGL2005-02217/ BOS.

References

Antsulevich, A. E., 2005. First finding of Cumacea crustaceans

in the Gulf of Finland. Vestnik Sankt-Peterburgskogo

Universiteta: Seriia 3—Biologiia 1: 84–87 (in Russian

with English summary).

Ba

˘

cescu, M., 1992. Cumacea II. Crustaceorum Catalogus 8:

175–468.

Ba

˘

cescu, M. & I. Petrescu, 1999. Ordre des Cumace

´

s (Cuma-

cea Krøyer, 1846). In Forest, J. (ed.), Traite

´

de Zoologie.

Anatomie, Syste

´

matique, Biologie. Tome VII (Fascicule

III A), Crustace

´

sPe

´

racarides. Me

´

moires de l’Institut Oc-

e

´

anographique, Monaco 19: 391–428.

Czerniavsky, V., 1868. Materialia ad zoographiam Ponticam

comparatum. Transactions of the first meeting of Russian

naturalists in Saint Petersburg, 1868: 19–136, 8 pls.

Derzhavin, A., 1912. Neue Cumaceen aus dem Kaspischen

Meer. Zoologischer Anzeiger 39: 273–284.

Dumont, H. J., 2000. Endemism in the Ponto-Caspian Fauna,

with special emphasis on the Onychopoda (Crustacea).

Advances in Ecological Research 31: 181–196.

Jones, N. S. & W. D. Burbanck, 1959. Almyracuma proximo-

culi gen. et spec. nov. (Crustacea, Cumacea) from

brackish water of Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Biological

Bulletin 116: 115–124.

Kudinova-Pasternak, R. K., 1972. Notes about the tanaidacean

fauna (Crustacea, Malacostraca) of the Kirmadec Trench.

Complex Research of the Nature of the Ocean. Publica-

tions Moscow University 3: 257–258.

Larsen, K. & T. Hansknecht, 2004. A new genus and species of

freshwater tanaidacean Pseudohalmyrapseudes aquadul-

cis (Apseudomorpha: Parapseudidae), from Northern

Territory, Australia. Journal of Crustacean Biology 24:

567–575.

Mordukhai-Boltovskoi, F. D. & N. N. Romanova, 1973. A new

genus of Cumacea from the Caspian Sea. Zoologicheskii

Zhurnal 52: 429–432.

Roccatagliata, D., 1981. Claudicuma platensis gen. et sp. nov.

(Crustacea, Cumacea) de la ribera argentina del Rı

´

odela

Plata. Physis (Buenos Aires) 39: 79–87.

Roccatagliata, D., 1991. Claudicuma platense Roccatagliata,

1981 (Cumacea): a new reproductive pattern. Journal of

Crustacean Biology 11: 113–122.

Sars, G. O., 1894. Crustacea Caspia, part II. Cumacea. Bulletin

de l’Academie Impe

´

riale des Sciences de St Petersburg

16: 297–338.

Sars, G. O., 1897. On some additional Crustacea from the

Caspian Sea. Annuaire du Muse

´

e Zoologique de

l’Acade

´

mie Imperiale des Sciences. St Petersburg 1897:

1–73, 8 pls.

Table 3 Global and per biogeographic region diversity (species number) of non-marine Cumacea and Tanaidacea

PA NA NT AT OL AU PAC World

Nannastacidae 1 (1) 1 (1) 2 (2)

Pseudocumatidae 19 (9) 19 (9)

Total Cumacea 19 (9) 1 (1) 1 (1) 21 (11)

Anarthruridae 1 (1) 1 (1)

Parapseudidae 2 (1) 2 (1)

Tanaidae 1 (1) 1 (1) 1 (1) 1 (1) 1 (1) 1 (1) 1 (1)

Total Tanaidacea 2 (2) 1 (1) 1 (1) 1 (1) 3 (2) 1 (1) 4 (3)

In brackets, number of genera. No records of these groups exist from Antarctica. PA: Palaearctic, NA: Nearctic, NT: Neotropical,

AT: Afrotropical, OL: Oriental, AU: Australasian, PAC: Pacific Oceanic Islands, ANT: Antarctic.

Hydrobiologia (2008) 595:225–230 229

123

Sars, G. O., 1914. Report on the Cumacea of the Caspian

Expedition 1904. Trudy KaspiıˇskoıˇE

´

kspeditzı¯ 1904

ghoda. 4: 1–34 (in Russian), 1–32 (in English), 12 pls.

Shiino, S. M., 1965. Tanaidacea from the Bismarck Archipel-

ago. Videnskabelige Meddelelser fra Dansk

Naturhistorisk Forening i Kjøbenhavn 128: 177–203.

Simpson, K. W., J. P. Fagnani, D. M. DeNicola & R. W. Bode,

1985. Widespread distribution of some estuarine

crustaceans (Cyathura polita, Chiridotea almyra, Almy-

racuma proximoculi) in the limnetic zone of the Lower

Hudson River, New York. Estuaries 8: 373–380.

Sowinski, W., 1893. Report on the Crustacea collected by Dr.

Ostroumow in the Sea of Azov. Zapiski Kievskago Ob-

shchestva Estestvoispytatelei 14: 289–405, (in Russian).

230 Hydrobiologia (2008) 595:225–230

123

FRESHWATER ANIMAL DIVERSITY ASSESSMENT

Global diversity of Isopod crustaceans (Crustacea; Isopoda)

in freshwater

George D. F. Wilson

Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2007

Abstract The isopod crustaceans are diverse both

morphologically and in described species numbers.

Nearly 950 described species (*9% of all isopods)

live in continental waters, and possibly 1,400 species

remain undescribed. The high frequency of cryptic

species suggests that these figures are underestimates.

Several major freshwater taxa have ancient biogeo-

graphic patterns dating from the division of the

continents into Laurasia (Asellidae, Stenasellidae)

and Gondwana (Phreatoicidea, Protojaniridae and

Heterias). The suborder Asellota has the most

described freshwater species, mos tly in the families

Asellidae and Stenasellidae. The suborder Phrea to-

icidea has the largest number of endemic genera.

Other primary freshwater taxa have small numbers of

described species, although more species are being

discovered, especially in the southern hemisphere.

The Oniscidea, although primarily terrestrial, has a

small number of freshwater species. A diverse group

of more derived isopods, the ‘Flabellifera’ sensu lato

has regionally important species richness, such as in

the Amazon River. These taxa are transitional

between marine and freshwater realms and represent

multiple colonisations of continental habitats. Most

species of freshwater isopods species and many

genera are narrow range endemi cs. This endemism

ensures that human demand for fresh water will place

these isopods at an increasing risk of extinction, as

has already happened in a few documented cases.

Keywords Isopoda Crustacea Gondwana

Laurasia Diversity feeding Reproduction

Habits Fresh water Classification

Introduction

The Isopoda are a diverse group of crustaceans, with

more than 10,300 species found in all realms from the

deepest oceans to the montane terrestrial habitats;

approximately 9% of these species live in continental

waters. Isopods are thought of as dorsoventrally

flattened, and indeed many species fit this morpho-

logical stereotype. Diverse taxa found in the deep sea

and those found in groundwater habitats depart

considerably from this generalised body plan. Pala-

eontogical and phylogenetic evidence (Brusca &

Wilson, 1991; Wilson & Edgecombe, 2003) suggests

that the ancestral isopod may have had a narrow

Guest editors: E. V. Balian, C. Le

´

ve

ˆ

que, H. Segers &

K. Martens

Freshwater Animal Diversity Assessment

Electronic supplementary material The online version of

this article (doi:10.1007/s10750-007-9019-z) contains supple-

mentary material, which is available to authorized users.

G. D. F. Wilson (&)

Invertebrate Zoology, Australian Museum, 6 College

Street, Sydney, NSW 2010, Australia

e-mail: buz.wilson@austmus.gov.au

123

Hydrobiologia (2008) 595:231–240

DOI 10.1007/s10750-007-9019-z

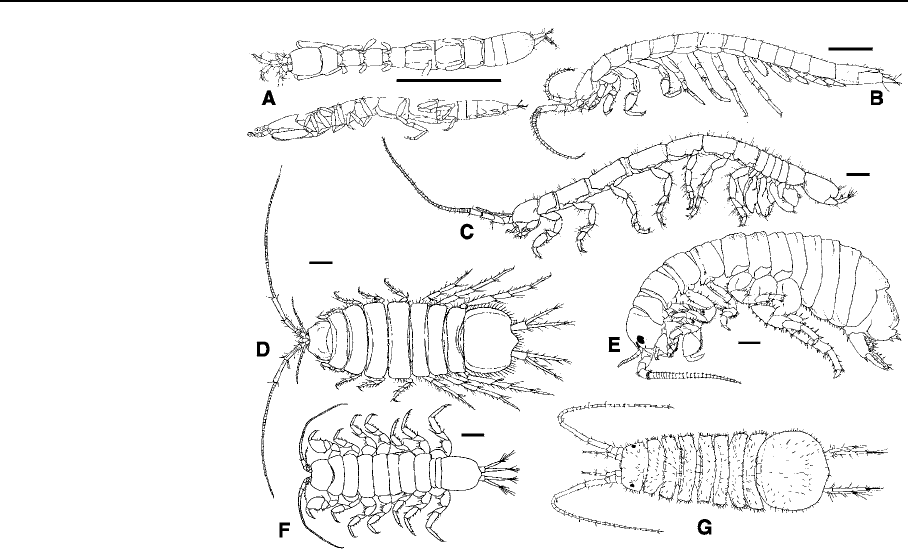

vaulted body with legs projecting ventrally (Fig. 1E,

Eophreatoicus, Amphisopidae). Freshwater taxa

include either typical flattened isopods (Fig. 1D, F,

G) or narrow body forms (Fig. 1B, C, E), along with

a few taxa that are thin and vermiform, often with

legs that emerge close to the dorsa l surface (Fig. 1A).

Other peculiarities of isopods include respiration

using their broad posterior limbs (swimming legs or

pleopods) with the heart positioned in the posterior

part of the body, and biphasic moulting, wherein the

back part of the body is cast off before the anterior

part. Limb forms are diverse in the isopods, but the

first walking leg (second thoracic limb) is modified

for grasping in most species.

Feeding

Isopods have a broad range of feeding types from

omnivory in Sphaeromatidae to carnivory in the

Cirolanidae. Oniscideans and Asellidae are well-

known as leaf litter shredders and have bacterial

endosymbionts to aid digestion (Zimmer, 2002,

Zimmer & Bartholme, 2003). Tainisopidae may be

carnivorous scavengers because they can be captured

using baited traps. Most freshwater isopods (e.g.

Asellota or Phreatoicidea) can be characterised as

generalised detritivores-omnivores, but may faculta-

tively choose other items. Phreatoicideans feed on

decaying vegetation and roots, or perhaps the micro-

flora and microfauna associated with these substrates

(Wilson & Fenwick, 1999), but on occasion will

engage in carnivory. Among the 942 described

species found in continental waters, the presumptive

feeding types (based on extrapolation from taxa

where habits are known) are as follows: 3.2% are

carnivores, 6.9% scavenger-carnivores, 9.9% ecto-

parasites, 0.4% herbivores, 6.1% omnivores and the

remaining 73.5% are detritivores-omnivores, mostly

Asellota and Phreatoicidea.

Reproduction

Isopods, like all peracarid crustaceans, have direct

development with the young brooded in a ventral

pouch until they are released as small adults. Isopods

have internal fertilisation (Wilson, 1991) that occurs

prior to the release of emb ryos into the marsupium,

unlike other peracarid crustaceans. Brood sizes range

from 4–5 young in tiny interstitial isopods to

hundreds in the parasitic forms, and lifetime

Fig. 1 Freshwater Isopoda,

a selection of body forms.

(A) Microcerberidae sp.

(interstitial, Western

Australia), dorsal and lateral

view; (B) Pygolabis sp.,

Tainisopidae (hypogean,

Western Australia); (C)

Phreatoicoides gracilis,

Hypsimetopidae (epigean,

Victoria Australia); ( D)

Asellus aquaticus, Asellidae

(epigean, Europe, from Sars

1897); (E ) Eophreatoicus

sp., Amphisopidae

(epigean, Northern

Territory Australia); (F),

Stenasellus chapmani,

Stenasellidae (hypogean,

Indonesia, from Coineau

et al. 1994; (G) Heterias

sp., Janiridae (hyporheic &

pholoteric, South America;

from Bowman et al. 1987).

Scale bars 1 mm, except for

A, 0.5 mm

232 Hydrobiologia (2008) 595:231–240

123

reproduction may be limited to one or several broods

in most species (Johnson et al., 2001). Many isopods,

especially the suborders Asellota and Oniscidea, have

secondary sexual features for intromission in both

males and females that are also useful for systemat-

ics. Brooding of the young, direct development and

internal fertilisation may be major contributory

factors in the high degree of endemism observed in

most isopod taxa (Wilson, 1991).

Habitats

Isopods occur in epigean lotic and lentic habitats (e.g.

Asellidae like the common European Asellus aquat-

icus and Phreatoicidae in Tasmania), but many live in

a variety of subterranean habitats. The Microcerberi-

dae are found interstitially in freshwater or marine

sands. Many families are limited to cavernicolous or

subterranean habitats, such as Stenasellidae, Microp-

arasellidae, or Tainisopidae. North American and

European members of the Asellidae can be both

epigean and hypogean (e.g. Turk et al., 1996; Lewis

& Bowman, 1981). Some taxa (e.g. Hypsimetopidae

or Heterias, Janiridae) could best be described as

infaunal, living in near subsurface habitats, either

burrowing among submerged roots, living in sub-

merged burrows of other animals (pholoteros) or in

the subsurface water of streams (hyporheos). A few

isopods occur in unusual habitats, such as Thermos-

phaeroma thermophilum in hot springs of the USA

southwest. Some oniscideans, which are ordinarily

terrestrial, have re-invaded the continental saline

waters (e.g. Haloniscus searlei) or even normal

freshwater (e.g. Trichoniscidae and Styloniscidae).

Australian collection records suggest that some

Philosciidae and Trichoniscidae may be amphibious

(see also Taiti & Humphreys, 2001; Tabacaru, 1999).

Methods

(See additional information on the article webpage).

The biodiversity of freshwater isopods is derived

from my research on the Phreatoicidea and Asellota,

and from the online ‘‘World List of Isopoda’’

(Kensley et al., 2005). The classification is derived

from that list (not as in Banerescu, 1990), but

includes the informal taxon ‘Flabellifera’ sensu lato

(see Wilson, 1999). The World List uses the tradi-

tional classification of the ‘Flabellifera’ that is known

to be paraphyletic (Brusca & Wilson, 1991; Wa

¨

gele,

1989; Tabacaru & Danielopol, 1999). The Microcer-

beridea includes two families, Microcerberidae and

Atlantasellidae (not Asellota as in Banarescu, 1990;

Wa

¨

gele, 1983; Jaume, 2001). The peculiar family

Calabozidae is classified as Oniscidea owing to its

possession of in-group genitalia and coxal plates

incorporated into the body (Brusca & Wilson, 1991).

Marine species, including those from anchialine cave

and marine beach interstitial environments, were

filtered out of the downloaded list, either using the

type habitat from the list or by consulting the original

literature. The data included species from saline

continental waters, such as Haloniscus. Subspecies

records were treated as species-level taxa. Unde-

scribed species (e.g. Heterias species) known to me

were added to the list where possible, although less

than 100 species were added. An estimate of the

unknown species was determined for the Phreatoici-

dea (Wilson in progress; see supplementary

information), and information from Gouws et al.

(2004, 2005). A diversity estimate for other isopod

groups used the simple known to unknown ratio from

the Phreatoicidea as applied to the other taxa

(Table 1). Although the assumption of similarity

between Phreatoicidea and other freshwater isopods

has obvious problems, this procedure at least pro-

vides an hypothesis for further refinement.

Species diversity

Of the entirely freshwat er isopods (marked with an

asterisk in Table 1), the Asellota has the most of the

942 described species, with the largest number of

species in the family Asellidae, followed by the

Stenasellidae. The Phreatoicidea have at least four

families with many undescribed species (see Table in

supplementary information) that may double the

number of described species. Other freshwater fam-

ilies have small numbers of described species,

although more species are being discovered as

surveys are carried out in the southern hemisphere.

The Protojaniridae are tiny and fragile, and may

require specialis ed techniques to recover them from

hypogean habitats; 12 species in five genera are

described, but more remain to be found. Recently,

Hydrobiologia (2008) 595:231–240 233

123

J. Pe

´

rez-Schultheiss in Chile sent specimens of a new

protojanirid; anot her new species is known from

northern Australia. The application of ‘‘known to

unknown’’ estimates from the Phrea toicidea to the

other freshwater isopods results in 62% more than

those known, or approximately a total of 2,630

species (Table 1).

Evidence from molecular studies suggest that this

estimate could be highly conservative. RAPD (ran-

dom amplified polymorphic DNA) studies on both

species of Asellidae and Stenasellidae (Baratti et al.,

1999; Verovnik et al., 2003) have uncovered previ-

ously unsusp ected diversity in well-known

populations of Stenasellus and Proasellus. Similar

results have been obtained from studies of genetic

variation using enzymatic loci (Proasellus: Ketmaier,

2002) or the mtDNA cytochrome oxidase I gene (CO-

I) (Stenasellus: Ketmaier et al., 2003). Cryptic spe-

cies in the epigean phreatoicidean genus

Mesamphisopus (Gouws et al., 2004, 2005) could

Table 1 Species Diversity of Freshwater Isopoda. Estimation method and classification explained in text and supplementary

material (see additional information)

Suborder Family Species, described

and new

Estimated

unknown species

Estimated

total diversity

PHREATOICIDEA

Stebbing, 1893

*

Amphisopidae Nicholls, 1943 36 48 84

*

Hypsimetopidae Nicholls, 1943 11 19 30

*

Incertae sedis (Crenisopus)1 1

*

Phreatoicidae Chilton, 1891 49 71 120

*

Ponderellidae Wilson & Keable, 2004 2 2

Subtotal, used for estimates other suborders 99 138 237

Unknown to Known ratio 1.39

ASELLOTA Latreille,

1803

*

Asellidae Rafinesque-Schmaltz, 1815 379 529 908

Janiridae G. O. Sars, 1897 76 106 182

Microparasellidae Karaman, 1933 73 102 175

*

Protojaniridae Fresi, Idato & Scipione, 1980 15 21 36

*

Stenasellidae Dudich, 1924 73 102 175

MICROCERBERIDEA

Lang, 1961

Microcerberidae Karaman, 1933 21 30 51

ONISCIDEA Latreille,

1803

*

Calabozoidae Van Lieshout, 1983 2 3 5

Philosciidae Kinahan, 1857 1 2 3

Scyphacidae Dana, 1852 5 7 12

Trichoniscidae Sars, 1899 1 2 3

‘FLABELLIFERA’

sensu lato

Aegidae Leach, 1815 1 2 3

Anthuridae Leach, 1814 19 27 46

Bopyridae Rafinesque-Schmaltz, 1815 33 46 79

Cirolanidae Dana, 1852 65 91 156

Corallanidae Hansen, 1890 4 6 10

Cymothoidae Leach, 1818 51 72 123

Entoniscidae Kossmann, 1881 4 6 10

Idoteidae Samouelle, 1819 4 6 10

Leptanthuridae Poore, 2001 3 5 8

Paranthuridae Menzies & Glynn, 1968 1 2 3

Sphaeromatidae Latreille, 1825 57 80 137

*

Tainisopidae Wilson, 2003 7 10 17

Total 994 1395 2625

(*Entirely freshwater families)

234 Hydrobiologia (2008) 595:231–240

123