Austin E W., Pinkleton B.E. Strategic Public Relations Management. Planning and Managing Effective Communication Programs

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

224 CHAPTER 11

TABLE 11.2

Levels of Measurement for Credibility

Nominal Level Which of the following companies do you find credible?

Ordinal Level Rank the following companies from most credible to least credible, with the

most credible company receiving a 5 and the least credible company receiving

a1.

Interval Level How credible are the following companies?

Not at Very

all credible credible

123 45

Ratio Level How many times in the last year have you wondered whether the following

companies were telling you the truth?

012345ormore

To choose the appropriate level, questionnaire designers need to con-

sider how they will use the information gathered. Sometimes, for example,

a client may wish to know whether people first heard about an organization

from the newspaper or from a friend. Other times, however, the organiza-

tion may need to know how often newspapers and friends are sources of

information or how credible the information received from these sources

seems. Each of these needs requires a different level of measurement.

The first level of measurement is called the nominal level, meaning names

or categories of things. This level of measurement is useful when an or-

ganization needs to know how many people fit into particular categories.

The possible answers for a nominal variable are mutually exclusive and

exhaustive. In other words, they have no overlap and include all possi-

ble responses. For example, a question assessing gender of the respondent

would include “male” and “female” (social scientists consider “gender”

a socially constructed identity rather than a category dictated by chro-

mosomes). A question assessing information sources could include “mass

media” and “interpersonal sources.” Including “mass media” and “news-

papers” would be redundant instead of mutually exclusive because the

newspaper is a form of mass media. Eliminating “interpersonal sources”

or including “friends” but not “coworkers” or “family” would not be ex-

haustive. Nominal variables can be useful, but little statistical analysis

can be performed using this type of variable. They have little explanatory

power, because people either fit a category or do not fit. They cannot fit a

little bit or a lot.

The second level of measurement is called the ordinal level, indicating

some meaningful order to the attributes. These questions have answers that

are mutually exclusive, exhaustive, and ordered in some way. A popular

type of ordinal question is the ranking question, as in “Please rate the

following five publications according to how much you like them, with

QUESTIONNAIRE DESIGN 225

the best one rated 1 and the worst one rated 5.” It would be possible to

know which publications do best and worst, but it would not be possible

to know whether Publication 2 is liked a lot better than Publication 3 or

just a little bit better.

The ranking question often creates problems and generally should be

avoided. It not only provides information of limited use but also frequently

confuses or frustrates respondents. Ranking is difficult to do and tends to

discourage respondents from completing a questionnaire. Sometimes re-

spondents may consider two or more items to be ranked in a tie, and other

times they may not understand the basis on which they are supposed to

determine differences. When asked to rank the corporate citizenship of

a group of companies, for example, respondents may not feel they have

enough information on some companies to distinguish them from others.

Respondents often rate several things as the same number, rendering their

response to the entire question useless to the analyst. If two or more items

are tied, they no longer are ranked. The answers no longer are mutually ex-

clusive, which makes the question of less use than even a nominal variable

would be.

Organizations that want to rank a group of things may find it better to let

rankings emerge from the data rather than trying to convince respondents

to do the ranking themselves. They can do this by creating a question or a

group of questions that can be compared with one another, such as, “Please

rate each of the following information sources according to how much you

like them, with a 4 indicating ‘a lot,’ a 3 indicating ‘some,’ a 2 indicating ‘not

much,’ and a 1 indicating ‘not at all.’” The mean score for each information

source then can be used to create a ranking.

The third level of measurement is the interval level. This is the most

flexible type of measure to use because it holds a lot of meaning, giving it

a great deal of explanatory power and lending itself to sensitive statistical

tests. As with the previous levels of measurement, the interval measure’s

responses must be mutually exclusive, exhaustive, and ordered. The order,

however, now includes equal intervals between each possible response.

For example, a survey could ask people to indicate how much they like a

publication on a 10-point scale, on which 10 represents liking it the most

and 1 represents liking it the least. It can be assumed that the respondent

will think of the distances separating 2 and 3 as the same as the distances

separating 3 and 4, and 9 and 10.

Most applied research—and some scholarly research—assumes percep-

tual scales such as strongly agree–strongly disagree or very important–not

important at all can be considered interval-level scales. Purists disagree,

saying they are ordinal because respondents might not place an equal

distance between items on a scale such as not at all . . . a little . . . some . . . a lot

in their own minds. Fortunately, statisticians have found that this usually

226 CHAPTER 11

does not present a major problem. Nevertheless, this is a controversial is-

sue (Sarle, 1994). Researchers must construct such measures carefully and

pretest them to ensure that they adhere to the equal-distance assumption

as much as possible.

The fourth level of measurement is the ratio scale, which is simply an

interval scale that has a true zero. This means the numbers assigned to

responses are real numbers, not symbols representing an idea such as “very

much.” Ratio scales include things such as the number of days respondents

report reading the newspaper during the past week (0–7 days), the number

of minutes spent reading the business section, or the level of confidence

they have that they will vote in the next presidential election (0–100%

likelihood of voting). This type of scale is considered the most powerful

because it embodies the most meaning.

TYPES OF QUESTIONS AND THE INFORMATION

EACH TYPE PROVIDES

Various strategies exist for eliciting responses at each level of analysis.

Keep in mind that respondents will find complex questions more difficult

and time consuming to answer. As a result, the survey designer has to

make trade-offs between obtaining the most meaningful information and

obtaining any information at all. For example, a lengthy and complex mail

survey may end up in the trash can more often than in the return mail.

Even if the questions are terrific, the few responses that come back may

not compensate for the loss of information resulting from the number of

nonresponses.

Likewise, people answering a telephone survey will find complicated

questions frustrating because they tend to comprehend and remember less

when hearing a question than when reading a question. This is the reason

telephone surveys often use generic response categories such as the Likert-

scale type of response, in which the answer range is: strongly agree, agree,

neutral, disagree, strongly disagree. People on the telephone often have

distractions in the background and other things they would rather be do-

ing, making them less involved in the survey. This makes it easier for them

to forget what a question was, what the response options were, or how

they answered a previous question on the survey.

For ease of response and analysis, questions on surveys usually are

closed ended, meaning respondents choose their favorite answer from a

list of possibilities. Open-ended questions, which ask a query but provide

space for individual answers instead of a response list, invite more in-

formation but are often skipped by respondents and are time consuming

to analyze afterward. As a result, surveys typically limit the number of

open-ended questions to 2 or 3 of 50. The primary types of closed-ended

QUESTIONNAIRE DESIGN 227

questions are the checklist, ranking scale, quantity/intensity scale, Likert-

type scale, frequency scale, and semantic differential scale.

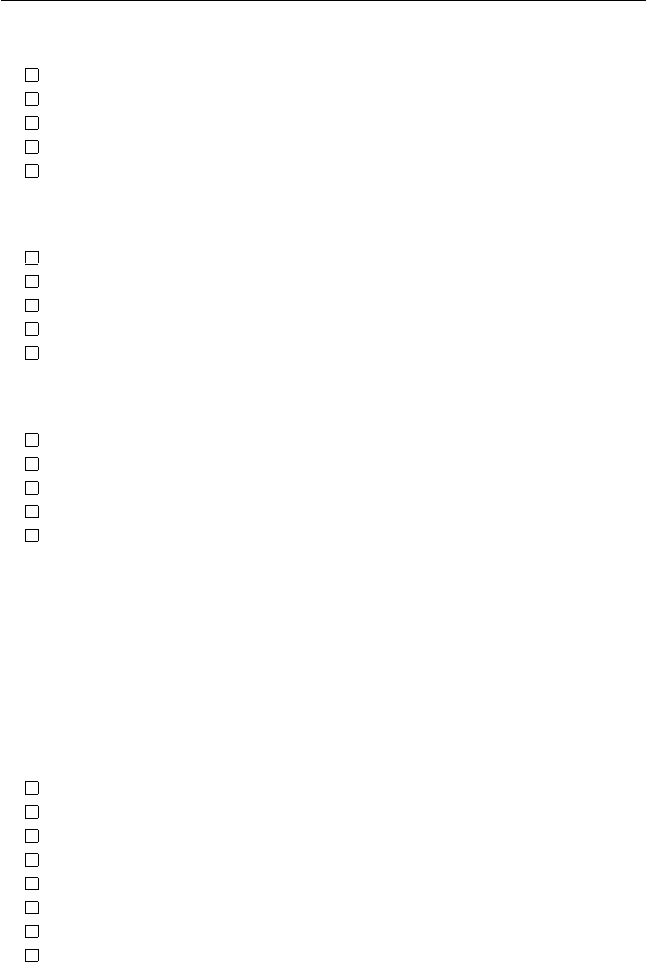

Checklists

The checklist is a nominal variable, providing categories from which re-

spondents can choose. They can be asked to choose only one response, or

all that apply.

Checklist example:

Please indicate whether you are male or female:

Male Female

Please indicate which of the following publications you have read this

week (check all that apply):

Newspapers News magazines Other magazines Newsletters

Ranking Scales

Ranking scales are ordinal variables, in which respondents are asked to

put items in the order they think is most appropriate. Ranking scales are

problematic because they incorporate a series of questions into a single

item, requiring respondents to perform a complex and often confusing

task. They must decide which choice should come first, which should come

last, which comes next, and so on until the whole series of comparisons is

completed.

Ranking example:

Please rank the following issues according to how important they are to

your decision about a congressional candidate this year. Put a 1 by the

issue most important to you anda5bytheissue least important to you:

Taxes

Economy

Environment

Education

Crime

Questionnaire designers can help respondents answer a ranking ques-

tion by breaking it into a series of questions, so that the respondents

do not have to do this in their heads. Although this method makes it

easier for respondents to answer ranking questions, it uses a lot of valuable

questionnaire space.

228 CHAPTER 11

Among the following issues, which is the most important to your deci-

sion about a congressional candidate this year?

Taxes

Economy

Environment

Education

Crime

Among the following issues, which is the next most important to your

decision about a congressional candidate this year?

Taxes

Economy

Environment

Education

Crime

Among the following issues, which is the least important to your

decision about a congressional candidate this year?

Taxes

Economy

Environment

Education

Crime

Quantity/Intensity Scales

The quantity/intensity scale is an ordinal- or interval-level variable, in

which respondents choose a location that best fits their opinion on a list of

options that forms a continuum.

Quantity/intensity example:

How much education have you completed?

Less than high school degree

High school diploma or GED

Some college (no degree; may be currently enrolled)

Vocational certificate or associate’s degree

College graduate (bachelor’s degree)

Some graduate work (no degree)

Master’s or other graduate professional degree

Doctoral degree

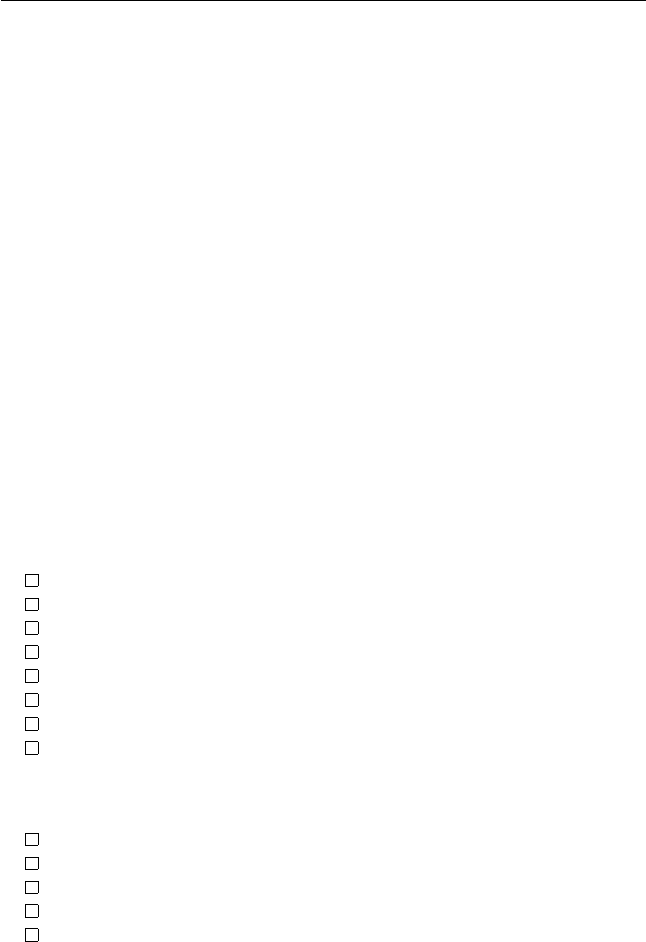

Likert-Type Scale

The most frequently used scale is known as the Likert scale.

QUESTIONNAIRE DESIGN 229

Likert scale example:

Please indicate whether you strongly agree, agree, disagree, or strongly

disagree with the following statement:

The Bestever Corporation is responsive to public concerns

Strongly agree

Agree

Disagree

Strongly disagree

Other variations on the Likert scale appear frequently on questionnaires.

Some popular response ranges include the following:

r

Very satisfied/Somewhat satisfied/Somewhat dissatisfied/Very un-

satisfied

r

Strongly oppose/Oppose/Support/Strongly support

r

Very familiar/Somewhat familiar/Somewhat unfamiliar/Very unfa-

miliar

r

A lot/Somewhat/Not much/Not at all

r

A lot/Some/A little/None

r

Always/Frequently/Seldom/Never

r

Often/Sometimes/Rarely/Never

r

Excellent/Good/Fair/Poor

Quantity/Intensity example:

Please indicate if the following reasons have been very important (VI),

somewhat important (SI), not very important (NVI), or not at all impor-

tant (NAI) to your decision whether to give to the Most important

Association in the past.

The tax benefits resulting from giving VI SI NVI NAI

Because you like being involved with the MA VI SI NVI NAI

Another variation of the Likert scale is known as the feeling thermometer,

which can be modified to measure levels of confidence, degrees of involve-

ment, and other characteristics. The feeling thermometer as presented by

Andrews and Withey (1976) used 10- or 15-point increments ranging from

0 to 100 to indicate respondents’ warmth toward a person, organization,

or idea.

Feeling thermometer example:

100 Very warm or favorable feeling

85 Good warm or favorable feeling

70 Fairly warm or favorable feeling

230 CHAPTER 11

60 A bit more warm or favorable than cold feeling

50 No feeling at all

40 A bit more cold or unfavorable feeling

30 Fairly cold or unfavorable feeling

15 Quite cold or unfavorable feeling

0 Very cold or unfavorable feeling

Yet another variation of the Likert scale uses pictorial scales, which can

be useful for special populations such as children, individuals lacking lit-

eracy, or populations with whom language is a difficulty. Often, the scales

range from a big smiley face (very happy or positive) to a big frowny face

(very unhappy or negative), or from a big box (a lot) to a little box (very

little).

Frequency Scales

The frequency scale is an interval or ratio scale. Instead of assessing how

much a respondent embraces an idea or opinion, the frequency question

ascertains how often the respondent does or thinks something.

Frequency example:

How many days during the past week have you watched a local televi-

sion news program?

7 days

6 days

5 days

4 days

3 days

2 days

1 day

0 days

About how many times have you visited a shopping mall during the

past month?

16 times or more

11–15 times

6–10 times

1–5 times

0 times

Sometimes frequency scales are constructed in ways that make it un-

clear whether equal distances exist between each response category, which

makes the meaning of the measure less clear and the assumption of

interval-level statistical power questionable.

QUESTIONNAIRE DESIGN 231

Frequency example:

In the past 6 months, how many times have you done the following

things?

Never 1–2 times 3–4 times 1–3 times 1 time More than

total a month a month a week once a week

Been offered an

alcoholic beverage

Attended a party where

alcohol was served

Drank an alcoholic

beverage

Hadfourormore

drinks in a row

Rode with a driver who

had been drinking

alcohol

Got sick from drinking

alcohol

Semantic Differential Scales

The semantic differential scale is an interval-level variable, on which re-

spondents locate themselves on a scale that has labeled end points. The

number of response categories between the end points is up to the ques-

tionnaire’s designer, but it is useful to have at least four response options.

More options make it possible for respondents to indicate nuances of opin-

ion; beyond a certain point, which depends on the context, a proliferation

of categories becomes meaningless or even confusing. An even number

of response categories forces respondents to choose a position on the is-

sue or refuse to answer the question, whereas an odd number of response

categories enables respondents to choose the neutral (midpoint) response.

Semantic differential example:

Please rate your most recent experience with the Allgetwell Hospital

staff:

Incompetent

Competent

Impolite

Polite

Helpful

Unhelpful

Semantic differential questions can provide a lot of information in a

concise format. Written questionnaires especially can include a list of se-

mantic differential items to assess the performance of an organization and

its communication activities. Because this type of question includes infor-

mation as part of the answer categories themselves, some consider these

232 CHAPTER 11

items more valid than Likert-scale items. For example, a Likert-scale ques-

tion asking if the staff seemed competent could bias respondents who do

not want to disagree with the statement, whereas a semantic differential

question that gives equal emphasis to “competent” and “incompetent” as

end points may elicit more honest answers. Psychologists have demon-

strated that agree/disagree question batteries can suffer from acquiesence

(Warwick & Lininger, 1975, p. 146), which occurs when people hesitate to

express disagreement.

Measuring Knowledge

Often, an organization wants to determine what people know about a topic.

One option is to give a true/false or multiple-choice test. The advantage of

the multiple-choice test is that, if carefully written, it can uncover misper-

ceptions as well as determine the number of people who know the correct

answers. The wrong answers, however, must be plausible. A second op-

tion is to ask open-ended questions in which people must fill in the blanks.

This requires a lot of work from the respondent but potentially provides

the most valid answers. A third option is to ask people how much they feel

they know, rather than testing them on what they actually know. This tech-

nique seems less intimidating to respondents. Finally, follow-up questions

can ask people how sure they are of a particular answer.

ENSURING CLARITY AND AVOIDING BIAS

Wording can affect the way people respond to survey questions. As a re-

sult, it is important to pretest for clarity, simplicity, and objectivity. Using

standardized questions that have been pretested and used successfully

can help prevent problems. Of course, because every communication is-

sue has unique characteristics, standardized batteries of questions suffer

from lacking specific context. Often, a combination of standard and unique

items serve the purpose well. When designing questions, keep the follow-

ing principles in mind:

1. Use words that are simple, familiar to all respondents, and relevant to the

context. Technical jargon and colloquialisms usually should be avoided.

At times, however, the use of slang may enhance the relevance of a ques-

tionnaire to a resistant target public. For example, asking college students

how often they “prefunk” could elicit more honest responses than asking

them how often they “use substances such as alcohol before going out to

a social function,” which is both wordy and could have a more negative

connotation to the students than their own terminology. When using spe-

cialized terms, it is important to pretest them to ensure the respondents

understand them and interpret them as intended. Try to choose words that

QUESTIONNAIRE DESIGN 233

will not seem patronizing, class specific, or region specific. Choosing to ask

about “pasta” instead of “noodles” when assessing audience responses to

messages about an Italian restaurant could alienate some respondents who

think “pasta” seems pretentious.

2. Aim for precision to make sure the meaning of answers will be clear. Avoid

vague terms. For example, the word often may mean once a week to some

people and twice a day to others. Recently could mean “this past week” or

“this past year.” Terms such as here and there do not set clear geographic

parameters.

Do not leave room for interpretation. People responding to a question

about how often in the past year they have donated to a charitable orga-

nization may consider each monthly contribution to a church a separate

donation. The sponsor of the survey, however, may have intended for re-

spondents to indicate to how many different organizations they have made

donations during the past year. Avoid hypothetical questions because peo-

ple often are not very good at, or may have trouble being honest about,

predicting their own behavior. Direct questions about cause or solutions

also may be difficult for respondents to answer validly (Fowler, 1995). It is

better to let the reasons for things emerge from the data analysis by look-

ing at the associations between attitudes and behaviors instead of asking

respondents to make those associations for the researcher.

Finally, because the use of negatives in a question can result in confu-

sion, use positive or neutral statements, providing respondents with the

opportunity to disagree. For example, instead of asking, “Do you think the

Neverong Corporation should not change its partner benefits policy?” a

survey can ask, “Do you think the Neverong Corporation’s partner benefits

policy should change or stay the same?”

3. Check for double-barreled questions. Each question must cover only one

issue. Asking if respondents rate staff as “polite and efficient,” for exam-

ple, makes it impossible for respondents to choose “polite but inefficient”

or “impolite but efficient” as their answer. Sometimes a double-barreled

question is subtle, and the problem occurs because a phrase requires re-

spondents to embrace an assumption they may not hold. For example,

asking “How likely are you to use this service on your next visit to Fun-

park?” assumes there will be a next visit.

4. Check for leading or loaded questions. A leading question prompts the

respondent in one direction instead of treating each possible response

equally. Asking the question, “How much did you enjoy your visit?” leads

respondents in the direction of a positive answer, whereas the question,

“How would you rate your visit?” allows enjoyment and disappointment

to be equivalent answer categories, making it easier for respondents to

choose the negative answer.

A loaded question biases the answer through the use of emotionally

charged words, stereotypes, or other words that give a subtle charge to a