Arora R. (ed.) Medicinal Plant Biotechnology

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

134 In vitro Saponin Production

Ngan, F., Shaw, P., But, P. and Wang, J. (1999) Molecular authentication of Panax species.

Phytochemistry 50, 787–791.

Nigra, H.M., Alvarez, M.A. and Giulietti, A.M. (1990) Effect of carbon and nitrogen sources on

growth and solasodine production in batch suspension cultures of Solanum eleagnifolium Cav.

Plant Cell Tissue and Organ Culture 21, 55–60.

Nocerino, E., Amato, M. and Izzo, A.A. (2000) The aphrodisiac and adaptogenic properties of

ginseng. Fitoterapia 71, S1–S5.

Odnevall, A., Björk, L. and Berglund, T. (1989) Rapid establishment of tissue cultures from seeds of

Panax ginseng and Panax pseudoginseng. Biochem. Physiol. Pflanzen. 185, 131–134.

Oleszek, W. and Marston, A. (ed.) (2000) Saponins in Food, Foodstuffs and Medicinal Plants.

Proceedings of the Phytochemical Society of Europe (45). Kluwer Academic Publishers,

Dordrecht–Boston/London.

Osbourn, A.E., Wubbern, J.P. and Daniels, M. (1997) Saponin detoxification by phytopathogenic

fungi. In: Stacey, G. and Keen, N.T.(eds) Plant Miocrobe Interactions. Vol. 2. International

Thomson Publishing, Chapman and Hall, New York, NY, USA, pp. 99–104.

Palazón, J., Cusidó, R.M., Bonfill, M., Mallol, A., Moyano, E., Morales, C. and Piol, M.T. (2003a)

Elicitation of different Panax ginseng root phenotypes for an improved ginsenoside production.

Plant Physiology and Biochemistry (Paris) 41, 1019–1025.

Palazón, J., Mallol, A., Eibl, R., Lettenbauer, C., Cusidó, R.M. and Piol, M.T. (2003b) Growth and

ginsenoside production in hairy root cultures of Panax ginseng using a novel bioreactor. Planta

Medica 69, 344–349.

Palazón, J., Moyano, E., Bonfill, M., Osuna, L.T., Cusidó, R.M. and Piol, M.T. (2006) Effect of

organogenesis on steroidal saponin biosynthesis in calli cultures of Ruscus aculeatus. Fitoterapia

77, 216–220.

Park, I.H., Kim, N.Y., Han, S.B., Kim, J.M., Kwon, S.W., Kim, H.J., Park, M.K. and Park, J.H.

(2002) Three new dammarane glycosides from heat processed ginseng. Archives of Pharmacol

Research (Seoul) 25, 428– 432.

Park, I.J., Piao, L.Z., Kwon, S.W., Lee, Y.J., Cho, S.Y. and Park, M.K. (2002) Cytotoxic dammarane

glycosides from processed ginseng. Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin (Tokyo) 50, 538–540.

Pauthe-Dayde, D., Rochd, M. and Henry, M. (1990) Triterpenoid saponin production in callus and

multiple shoot cultures of Gypsophila spp. Phytochemistry 29, 483–487.

Proctor, J.T.A. and Bailey, W.G. (1987) Ginseng: Industry, botany and culture. Horticultural Reviews

9, 187–236.

Radman, R., Saez, T., Bucke, C. and Keshavarz, T. (2003) Elicitation of plants and microbial cell

systems. Biotechnology and Applied Biochemistry. 37, 91–102.

Rao, R.S. (2000) Biotechnological production of phytopharmaceuticals. Journal of Biochemistry

Molecular Biology and Biophysics 4, 73–112.

Rao, R.S. and Ravishankar, G.S. (2002) Plant cell cultures: chemical factories of secondary

metabolites. Biotechnology Advances 20, 101–153.

Roberts, S.C. and Shuler, M.L. (1997) Large scale plant cell culture. Current Opinion in

Biotechnology 8, 154–159.

Schlag, E.M. and McIntosh, M.S. (2006) Ginsenoside content and variation among and within

American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius L.) populations. Phytochemistry 67, 1510–1519.

Schultz, V., Hänsel, R. and Tyler, V. (1998) Rational Phytotherapy: A Physician's Guide to Herbal

Medicine. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

Sevon, N. and Oksman-Caldentey, K.M. (2002) Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated transformation:

root cultures as source of alkaloids. Planta Medica 68, 859–868.

Shibata, S. (2001) Chemistry and cancer preventing activities of ginseng saponins and some related

triterpenoid compounds. Journal

of Korean Medical Science 16, S28–S37.

Shuler, M. (2001) Bioprocess Engineering: Basic Concepts. 2nd edn. Prentice Hall, Englewood

Cliffs, NJ, USA.

Sivakumar, G., Yu, K.W., Hahn, E.J. and Paek, K.Y.(2005) Optimisation of organic nutrients for

ginseng hairy roots production in large scale bioreactors. Current Science 89, 641–649.

In vitro Saponin Production 135

Srivastava, S. and Srivastava, A.K. (2007) Hairy root culture for mass-production of high-value

secondary metabolites. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology 27, 29–43.

Sticher, O. (1998) Getting to the root of ginseng. Chemtech 28, 26–32.

Susan, M., Merce, B., Lidia, O., Elisabeth, M., Jaime, T., Rosa, C., Teresa, P.M. and Javier, P. (2006)

The effect of methyl jasmonate on triterpene and sterol metabolisms of Centella asiatica, Ruscus

aculeatus and Galphimia glauca cultured plants. Phytochemistry 67, 2041–2049.

Tenea, G.N., Calin, A. and Cucu, N. (2008) Manipulation of root biomass and biosynthetic potential

of Glycyrrhiza glabra L. plants by Agrobacterium rhizogenes mediated transformation. Romanian

Biotechnology Letters 13, 3922–3932.

Thanh, N.T., Murthy, H.N., Yu, K.W., Hahn, E.J. and Paek, K.Y. (2005) Methyl jasmonate elicitation

enhanced synthesis of ginsenoside by cell suspension cultures of P.ginseng in 5-l balloon type

bubble bioreactors. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 67, 197–201.

Thanh, N.T., Murthy, H.N., Yu, K.W., Jeong, C.S., Hahn, E.J. and Paek, K.Y. (2006) Effect of

oxygen supply on cell growth and saponin production in bioreactor cultures of

Panax ginseng. Journal of Plant Physiology 163, 1337–1341.

Ushiyama, K. and Hibino, K. (1997) Commercial production of ginseng by plant cell cultures.

American Chemical Society 213 National Meeting, San Francisco, CA, Abstract Pt.1, AGFD057.

Ustundag, O.G. and Mazza, G. (2007) Saponins: Properties, applications and processing. Critical

Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 47, 231–258.

Varshney, A., Dhawan, V. and Srivastava, P.S. (2001) Ginseng: wonder drug of the world. In: Khan,

I.A. and Khanum, A. (eds) Role of Biotechnology in Medicinal and Aromatic Plants .Vol. IV.

Ukaaz Publications, Hyderabad, India, pp. 26–41.

Veersham, C. (2004) In: Elicitation Medicinal Plant Biotechnology, CBS Publishers, India, pp. 270–

293.

Verpoorte, R., Contin, A. and Memelink, J. (2002) Biotechnology for the production of plant

secondary metabolites. Phytochemical Reviews 1, 13–25.

Wagner, F. and Vogelmann, H. (1977) Cultivation of plant tissue cultures in bioreactors and

formation of secondary metabolites. In : Barz, W., Reinhard, E.and Zenk, M.H. (eds) Plant Tissue

Culture and its Biotechnological Application, Springer, New York, pp. 245–252.

Wang, W. and Zhong, J.J. (2002) Manipulation of ginsenoside heterogeneity in cell cultures of Panax

notoginseng by addition of jasmonates. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering 93, 48–53.

Wang, W., Zhang, Z.Y. and Zhong, J.J. (2005a) Enhancement of ginsenoside biosynthesis in high-

density cultivation of Panax notoginseng cells by various strategies of methyl jasmonate

elicitation. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 67, 752–758.

Wang, W., Zhao, Z.J., Xu, Y., Qian, X. and Zhong, J.J. (2005b) Efficient elicitation of ginsenoside

biosynthesis in cell cultures of Panax notoginseng by using self-chemically synthesized

jasmonates. Biotechnology and Bioprocess Engineering 10, 162–165.

Wang, W., Zhao, Z.J., Xu, Y., Qian, X. and Zhong, J.J. (2006) Efficient induction of ginsenoside

biosynthesis and alteration of ginsenoside heterogeneity in cell cultures of Panax notoginseng by

using chemically synthesized 2-hyroxylethyl jasmonate. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology

70, 298–307.

Wang, X., Proctor, J.T.A., Kakuda, Y., Krishnaraj, S. and Saxena, P.K. (1999) Ginsenosides in

American ginseng: Comparison of in vitro derived and field-grown plant tissues. Journal of Herb,

Spices and Medicinal Plants 6, 1–10.

Washida, D., Shimomura, K., Nakajima, Y., Takido, M. and Kitanaka, S. (1998) Ginsenosides in

hairy roots of a Panax hy

brid. Phytochemistry 49, 2331–2335.

Washida, D., Shimomura, K., Takido, M. and Kitanaka, S. (2004) Auxins affected ginsenoside

production and growth of hairy roots in Panax hybrid. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin

27, 657–660.

Watanabe, K., Yano, S.Y. and Yamada, Y. (1982) Selection of cultured plant cell lines producing

high levels of biotin. Phytochemicals 21, 513–516.

WHO (1999) Monographs on Selected Medicinal Plants, Vol. 1. World Health Organization, Geneva

136 In vitro Saponin Production

Woo, S.S., Song, J.S., Lee, J.Y., In, D.S., Chung, H.J., Liu, J.R. and Choi, D.W. (2004) Selection of

high ginsenoside producing hairy root lines using targeted metabolic analysis. Phytochemistry 65,

2751–2761.

Wu, J. and Ho, K.P. (1999) Assessment of various carbon sources and nutrient feeding strategies for

Panax ginseng cell culture. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 82, 17–26.

Wu, J. and Lin, L. (2002) Elicitor like effects of low energy ultrasound on plant (Panax ginseng)

cells: induction of plant defense responses and secondary metabolite production. Applied

Microbiology and Biotechnology 59, 51–57.

Wu, J.Y., Wong, K., Ho, K.P. and Zhou, L.G. (2005) Enhancement of saponin production in Panax

ginseng cell culture by osmotic stress and nutrient feeding. Enzyme and Microbial Technology 36,

133–138.

Xiaojie, X., Xiangyang, H., Neill, S.J., Jianying, F. and Weiming, C. (2005) Fungal elicitor induces

singlet oxygen generation, ethylene release and saponin synthesis in cultured cells of Panax

ginseng C.A. Meyer. Plant and Cell Physiology 46, 947–954.

Xu, H., Kim, Y.K., Jin, X., Lee, S.Y. and Park, S.U. (2008) Rosmarinic acid biosynthesis in callus

and cell cultures of Agastache rugosa Kuntze. Journal of Medicnal Plant Research 2, 237–241.

Yadav, S., Mathur, A., Mishra, P., Singh, M., Gupta, M.M., Alam, M. and Mathur, A.K. (2007) In

vitro growth and asiaticoside production in shoot cultures of Centella asiatica L.. In: Kukreja,

A.K. et al. (eds) Proceedings of National Symposium on Plant Biotechnology: New Frontiers, pp.

373–378.

Yamamoto, O. and Kamura, K. (1997) Production of saikosaponin in cultured roots of Bupleurum

falcatum. Plant Tissue Culture and Biotechnology 3, 138–147.

Yang, D.C. and Choi, Y.E. (2000) Production of transgenic plants of Panax ginseng from

Agrobacterium-transformed hairy roots. Plant Cell Reports 19, 491–496.

Yao, H. and Zhong, J.J. (1999) Improved production of ginseng polysaccharide by adding

conditioned medium to Panax notoginseng cell cultures. Biotechnological Technology 13, 347–

349.

Yoshikawa, M., Sugimoto, S., Nakamura, S. and Matsuda, H. (2007) Medicinal flowers.XI.

Structures of new dammarane-type triterpene diglycosides with hydroperoxide group from flower

buds of Panax ginseng. Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin (Tokyo) 55, 571–576.

Yoshikawa, T. and Furuya, T. (1987) Saponin production by cultures of Panax ginseng transformed

with Agrobacterium rhizogenes. Plant Cell Reports 6, 449–453.

Yoshimatsu, K., Yamaguchi, H. and Shimomura, K. (1996) Traits of Panax ginseng hairy roots after

cold storage and cryopreservation. Plant Cell Reports 15, 555–560.

Yu, C.J., Murthy, H.N., Jeong, C.S., Hahn, E.J. and Paek, K.Y. (2005) Organic germanium stimulates

the growth of ginseng adventitious roots and ginsenoside production. Process Biochemistry 40,

2959–2961.

Yu, K.W., Gao, W.Y., Son, S.H. and Paek, K.Y. (2000) Improvement of ginsenoside production by

jasmonic acid and some other elicitors in hairy roots culture of ginseng (Panax ginseng C.A.

Meyer). In vitro Cellular and Developmental Biology– Plant 36

, 424–428.

Yu, K.W., Gao, W., Han, E.J. and Paek, K.Y. (2002) Jasmonic acid improves ginsenoside

accumulation in adventitious root culture of Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer. Biochemical

Engineering 11, 211–215.

Yu, K.W., Murthy, H.N., Hahn, E.J. and Paek, K.Y. (2005) Ginsenoside production by hairy root

cultures of Panax ginseng: influence of temperature and light quality. Biochemical Engineering

Journal 23, 53–56.

Zhang, Y.H. and Zhong, J.J. (1997) Hyperproduction of ginseng saponin and polysaccharide by high

density ultivation of Panax ginseng cells. Enzyme and Microbial Technology 21, 59–63.

Zhang, Y.H., Zhong, J.J. and Yu, J.T. (1996a) Effect of nitrogen source on cell growth and production

of ginseng saponin and polysaccharide in suspension cultures of Panax notoginseng.

Biotechnology Progress 12, 567–571.

Zhang, Y.H., Zhong, J.J. and Yu, J.T. (1996b) Enhancement of ginseng saponin production in

suspension cultures of Panax notoginseng: Manipulation of medium sucrose. Journal of

Biotechnology 51(1), 49–56.

In vitro Saponin Production 137

Zhang, Z.Y. and Zhong, J.J. (2004) Scale-up of centrifugal impeller bioreactor for hyperproduction of

ginseng saponin and polysaccharide by high-density cultivation of Panax notoginseng cells.

Biotechnology Progress 20, 1076–1081.

Zhao, J., Davis, L.C. and Verpoorte, R. (2005) Elicitor signal transduction leading to production of

plant secondary metabolites. Biotechnology Advances 23, 283–333.

Zhong, J.J. (2000) Production of ginseng saponins by cell suspension cultures of Panax notoginseng

in bioreactors. In: Oleszek, W. and Marston, A. (eds) Saponins in Food Feedstuffs and Medicinal

Plants. Proc. Phytochemical Society of Europe, Vol. 45. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht,

Boston, London, pp. 163–170.

Zhong, J.J. (2003) Biochemical engineering of the production of plant specific secondary metabolites

of cell suspension cultures. Advances in Biochemical Engineering Biotechnology 72, 1–26.

Zhong, J.J. and Wang, D.J. (1996) Improvement of cell growth and production of ginseng saponin

and polysaccharide in suspension cultures of Panax notoginseng: Cu

2+

effect. Journal of

Biotechnology 46, 69–72.

Zhong, J.J. and Wang, S.J. (1998) Effects of nitrogen source on the production of ginseng saponin

and polysaccharide by cell cultures of Panax quinquefolium. Process Biochemistry 33, 671–675.

Zhong, J.J. and Yue, C.J. (2005) Plant cells: secondary metabolite heterogeneity and its manipulation.

Advances in Biochemical Engineering Biotechnology 100, 53–88.

Zhong, J.J. and Zhu, Q.X. (1995) Effect of initial phosphate concentration on cell growth and ginseng

saponin production by suspended cultures of Panax notoginseng. Applied Biochemistry and

Biotechnology 55, 241–247.

Zhong, J.J., Meng, X.D., Zhang, Y.H. and Liu, S. (1997) Effective release of ginseng saponin from

suspension cells of Panax notoginseng. Biotech. Tech. 11, 241–243.

Zhou, L., Cao, X., Zhang, R., Peng, Y., Zhao, S. and Wu, J. (2007) Stimulation of saponin production

in Panax ginseng hairy roots by two oligosaccharides from Paris polyphalla var. yunnanensis.

Biotechnology Letters 29, 631–634.

Zhou, Y., Hirotani, M., Rui, H. and Furuya, T. (1995) Two triglycosidic triterpene astragalosides

from hairy root cultures of Astragalus membranaceus. Phytochemistry 38, 1407–1410.

©CAB International 2010. Medicinal Plant Biotechnology 138

(ed. Rajesh Arora)

Chapter 9

Podophyllotoxin and Related Lignans:

Biotechnological Production by In vitro Plant

Cell Cultures

Iliana Ionkova

Introduction

The aryltetralin lignan podophyllotoxin (PTOX) is a natural occurring lignan derived from

the roots and rhizomes of the Himalayan Podophyllum hexandrum and the American

Podophyllum peltatum L. (Podophyllaceae ~Berberidaceae) (Ionkova, 2007; Arora et al.,

2008). Podophyllum is a genus of six species of herbaceous perennial plants in the family

Berberidaceae, native to eastern Asia (five species) and eastern North America (one

species, P. peltatum). They are woodland plants, typically growing in colonies derived

from a single root. This small group of perennials (commonly called May Apples) is

originally from North America, the Himalayas and western China. They grow from 12 to

18 inches high and have large, deeply lobed leaves on long, fleshy stems, which rise

straight up from the soil. The name Podophyllum is taken from podos, a foot, and phyllon,

a leaf, and refers to the resemblance of the leaves to a duck’s foot. A drug known as

podophyllin is made from the rhizomes of these plants. P. hexandrum has pretty leaves that

are divided into three lobes. They completely unfurl after the plant has bloomed and are

dark green splotched with brown. In the spring, white or pale pink, six-petalled flowers are

borne at the ends of stout stems; these are followed by fleshy, oval, red berries. The

perennial herb Podophyllum hexandrum (syn. P. emodi), bearing the common names

Himalayan mayapple or Indian Mayapple, is native to the lower elevations in and

surrounding the Himalaya (Gupta and Sethi, 1983; Arora et al., 2008). It is low to the

ground with glossy green, drooping, lobed leaves on its few stiff branches, and it bears a

pale pink flower and bright red-orange bulbous fruit. The ornamental appearance of the

plant makes it a desirable addition to woodland-type gardens. It can be propagated by seed

or by dividing the rhizome. It is very tolerant of cold temperatures, as would be expected of

a Himalayan plant, but it is not tolerant of dry conditions.

Biotechnological Production of Lignans 139

Medicinal Use

Lignans have a long history of medicinal use as the first records date back over 1000 years

(Kelly and Hartwell, 1954). The roots of wild Chervil (Anthriscus sylvestris L. Apiaceae),

containing several lignans, including deoxypodophyllotoxin, were used in a salve for

treating cancer (Cockayne, 1961). Another source from 400–600 years ago reveals the use

of the resin, derived from an alcoholic extract of the roots and rhizomes of Podophyllum

perennials as a catharctic and poison, both by the natives of the Himalayas and the

American Penobscot Indians of Maine (Ayres and Loike, 1990). Throughout the years,

lignan-containing plant products were used for a wide number of ailments in Chinese

medicine – roots of Kadsura coccinea Hance. ex Benth. (Schizandraceae) for treatment of

rheumatoid arthritis, gastric and duodenal ulcers (Tu, 1977), Japanese – Fraxinus japonica

Blume ex K. Koch. (Oleaceae) (Kariyone and Kimurta, 1976; Kodaira, 1983) – diuretic,

antipyretic, an analgesic and antirheumatic agent. The bark of Olea europaea L. (Oleaceae)

has been studied (Tsukamoto et al., 1984) for its antipyretic, antirheumatic, tonic and

scrofula remedy actions.

The Podophyllum plant is poisonous but when processed has medicinal properties. The

rhizome of the plant contains a resin, known generally and commercially as Indian

Podophyllum Resin, which can be processed to extract podophyllotoxin, or podophyllin, a

neurotoxin. It has been historically used as an intestinal purgative and emetic, salve for

infected and necrotic wounds, and inhibitor of tumour growth. The North American variant

of this Asian plant contains a lower concentration of the toxin but has been more

extensively studied. All the parts of the plant, excepting the fruit, are poisonous. Even the

fruit, though not dangerously poisonous, can cause unpleasant indigestion. Podophyllum

gets its name from the Greek words podos and phyllon, meaning foot shaped leaves.

Podophyllum rhizomes have a long medicinal history among native North American tribes

who used a rhizome powder as a laxative or an agent that expels worms (anthelmintic). A

poultice of the powder was also used to treat warts and tumourous growths on the skin.

Podophyllotoxin is a plant-derived compound used to produce two cytostatic drugs,

etoposide and teniposide. The substance has been primarily obtained from the American

mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum). The Himalayan mayapple (Podophyllum hexandrum or

P. emodi) contains this constituent in a much greater quantity, but is endangered in the

wild. The substance they contain (podophyllotoxin or podophyllin) is used as a purgative

and as a cytostatic. Posalfilin is a drug containing podophyllin and salicylic acid that is

used to treat the plantar wart. Several podophyllotoxin preparations are on the market for

dermatological use to treat genital warts. Since the total synthesis of podophyllotoxin is an

expensive process, availability of the compound from natural renewable resources is an

important issue for pharmaceutical companies that manufacture these drugs (Moraes et al.,

2002). In recent years, P. hexandrum has been extensively investigated for its potent

radioprotective properties (Arora et al., 2005, 2007, 2010a,b; Chawla et al., 2006; Singh et

al., 2009).

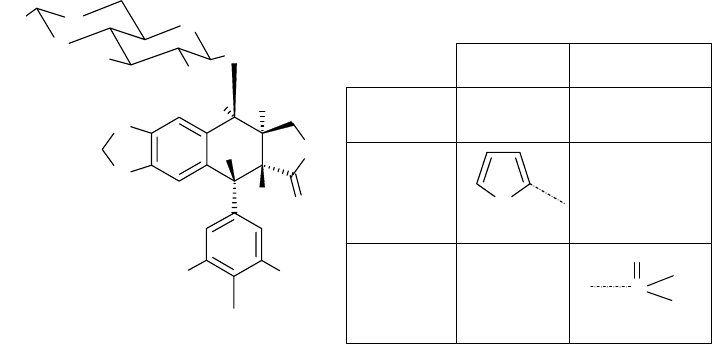

The lignan podophyllotoxin, occurring in Podophyllum emodi Wall. ex Royle and

Podophyllum peltatum L., is the starting compound for the semi-synthesis of the anticancer

drugs. It is currently being used as a lead compound for the semi-synthesis of anticancer

drugs etoposide, teniposide and etopophos (Fig. 9.1), which are used for the treatment of

lung and testicular cancers and certain leukaemias (Stahelin and Wartburg, 1991; Imbert,

140 Biotechnological Production of Lignans

1998). The drug etoposide (VePesid®) is the semisynthetic derivative of podophyllotoxin,

and is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for various types of

cancer. Currently, extracts of the podophyllum plant are used also in topical medications

for genital warts, HIV-related oral hairy leukoplakia, and some skin cancers. Preliminary

research also shows that CPH 82, an oral form of Podophyllum emodi composed of two

purified semisynthetic lignan glycosides, may be useful in treating rheumatoid arthritis.

However, when used orally, Podophyllum can be lethal and should be avoided.

R

1

R

2

Etoposide Me H

Teniposide

S

H

Etopophos Me

P

OH

OH

O

Fig. 9.1. Structures of etoposide, teniposide and etopophos.

Supply of podophyllotoxin

The supply of podophyllotoxin depends mainly on its extraction from roots and rhizomes

of Podophyllum hexandrum Royle (from Himalayas region) and Podophyllum peltatum L.

(North America), which contain 4% and 0.2% of the active substance on a dry mass basis,

respectively. Those resources are, however limited, because of the intensive collection of

the plants, lack of cultivation and the long juvenile phase and poor reproduction capacities

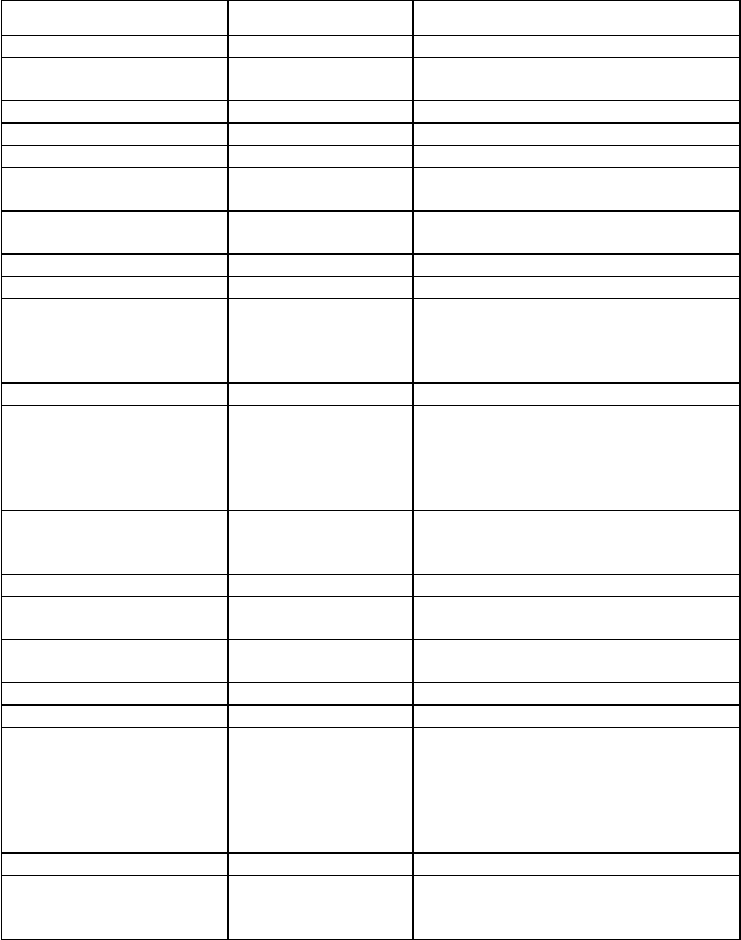

of the plant (Van Uden, 1992). Podophyllotoxin and related compounds (Fig. 9.2) are not

only present in Podophyllaceae, but also in e.g. Juniperaceae, Lamiaceae and Linaceae

(Petersen and Alfermann, 2001). A detailed phytochemical analysis of the lignans in the

Linaceae has been done in the groups of Ionkova (Sofia, Bulgaria), T.J. Schmidt (Münster,

Germany) and A.W. Alfermann (Düsseldorf, Germany). Genera in which abundance of

PTOX has been reported are Linum (Linaceae) (Ionkova, 2007; Broomhead and Dewick,

1990a; Konuklugil, 1996a; Vasilev et al., 2005a,b; Konuklugil et al, 2007). Juniperus

(Cupressaceae) (Kupchan, 1965; San Feliciano et al., 1989a,b), Hyptis (Lamiaceae) (Kuhnt

et al., 1994), Thymus (Lamiaceae), Teucrium (Lamiaceae), Nepeta (Lamiaceae)

(Konuklugil, 1996b), Dysosma (Berberidaceae) (Yu et al., 1991), Diphylleia

(Berberidaceae) (Broomhead and Dewick, 1990a), Jeffersonia (Berberidaceae) (Bedir et

al., 2002) and Thuja (Cupressaceae) (Muranaka et al, 1998).

General approaches to the chemical synthesis of podophyllotoxin derivatives (Canel et

al., 2000) and chemical synthesis of lignans (Ward, 2003) have been proposed, however,

H

3

CO

OCH

3

O

O

O

O

H

H

H

H

O

O

O

O

OH

OH

R

1

OR

2

Biotechnological Production of Lignans 141

an efficient commercially viable route to the synthesis of podophyllotoxin is still to be

sought.

Need for production of podophyllotoxin and related lignans by plant in vitro cultures

The supply of podophyllotoxin depends mainly on its extraction from roots and rhizomes

of Podophyllum hexandrum Royle (from Himalayas region) and Podophyllum peltatum L.

(North America), which contain 4% and 0.2% of the active substance on a dry mass basis,

respectively. Those resources are, however limited, because of the intensive collection of

the plants, lack of cultivation and the long juvenile phase and poor reproduction capacities

of the plant (Van Uden, 1992).

In the coming decades, several new enabling technologies will be required to develop

the next generation of advanced plant-based pharmaceuticals. With modern biotechnology,

it has become possible to use plant cells for the production of specific pharmaceuticals.

Using the right culture medium and appropriate phytohormones it is possible to establish in

vitro cultures of almost every plant species. Starting from callus tissue, cell suspension

cultures can be established that can even be grown in large bioreactors. Moreover, the

biotechnological production of these plant products is more environmentally friendly way

than is currently occurring.

Malignant diseases are the second leading cause of mortality within the human

population. Despite the serious progress in establishing and introducing novel specifically-

targeted drugs the therapy of these diseases remains a severe medical and social problem.

Some of the most effective cancer treatments to date are natural products or compounds

derived from plant products. Seven of the most consumed anticancer drugs are of plant

origin: etoposide, teniposide, taxol, vinblastine, vincristine, topotecan, and irinotecan. They

are some of the most vigorous products in cancer therapy and are still derived from plants

since the chemical synthesis of the chiral molecules is not economic (Dechamp, 1999).

Market prices for the plant-derived anticancer drugs are quite high: 1 kg of vincristine

(Catharanthus alkaloid) costs about US$20,000 and the annual world market is about

US$5 million per year. Isolation of pharmaceuticals from plants is difficult due to their

extremely low concentrations. The industry currently lacks sufficient methods for

producing all of the desired plant-derived pharmaceutical molecules. Some substances can

only be isolated from extremely rare plants. The biotechnological approach offers a quick

and efficient method for producing these high-value medical compounds in cultivated cells.

In the future, a new production method may also offer alternatives to other highly

expensive drugs.

Biotechnological production in plant cell cultures is an attractive alternative but has so far

had only limited commercial success (for example, paclitaxel or Taxol), due to a lack of

understanding of the complex multistep biosynthetic events leading to the desired end-

product. Discoveries of cell cultures capable of producing specific medicinal compounds at

a rate similar or superior to that of intact plants have accelerated in the last few years in

Bulgaria and other countries in Europe.

Lignans are a large group of phenolic compounds defined as -dimers of

phenylpropane (C6C3) units. This widely spread group of natural products possesses a long

and remarkable history of medicinal use in the ancient cultures of many peoples. The first

unifying definition of lignans was made by Howarth in 1936, who described them as a

group of plant phenols with a structure determined by the union of two cinnamic acid

142 Biotechnological Production of Lignans

residues or their biogenetic equivalents (Howarth, 1936). According to IUPAC

nomenclature, lignans are 8,8-coupled dimmers of coniferyl alcohol or other cinnamyl

alcohols (Moss, 2000). Lignans occur in many plant species, but only in low

concentrations. The biotechnological part focuses on alternative production systems for

these natural compounds, because the plant in vitro cultivation has several advantages over

collecting plants from fields (Alfermann et al., 2003). Growing plant cells permit a stricter

control of the quality of the products as well as their regular production without

dependence on the variations of natural production resulting from climate and socio-

political changes in their countries of origin. Problems connected with gathering, storing

(in special conditions), processing and disposal of huge amounts of biomass, connected

with extraction of active substances from in vivo plants are also solved. Suspension cultures

are of special interest due to their high growth rate and short cycle of reproduction.

Another advantage is the fact that undifferentiated plant cells, maintained in a liquid

medium, possess a high metabolic activity due to which considerably high yields of

secondary products can be achieved in short terms (from 1 to 3 weeks of cultivation). This

raises the question of investigation of in vitro cultures of new plant species for the

production of podophyllotoxin derivatives (Fuss, 2003). In Table 9.1, the accumulation of

lignans in plant tissue and organ cultures has been summarized.

Although there are many examples for the synthesis of podophyllotoxin and its

derivatives in plant cell and tissue cultures, the in vitro production still has to cope with

multiple tasks for the purpose of finding economically feasible paths for enhancing

production. The plant-specific secondary products as a podophyllotoxin and its derivatives

were long considered as a major limitation for an extensive use of plant-made

pharmaceuticals in human therapy.

Production advantages provided by plant in vitro cultures

The two principal advantages of plant-based production systems are:

1. Scalability: no other production system offers the potential scalability of plant

products. High-value products could be produced in sufficient amounts in plant cell

culture and will allow product manufacture on a massive scale that can match global

demand.

2. Adaptability: In the post-genomic era, it has become feasible to engineer plant cell and

tissue cultures, not only to produce complex proteins but also to produce high-value

secondary metabolites or entirely novel structures (such as new lead compounds for

pharmaceutical industry) (Stakeholders proposal, 2005).

Additional major advantages of a cell culture system over the conventional cultivation of

whole plants are:

1. Useful compounds can be produced under controlled conditions independent of

climatic changes or soil conditions;

2. Cultured cells would be free of microbes and insects;

3. The cells of any plants, tropical or alpine, could easily be multiplied to yield their

specific metabolites;

4. Automated control of cell growth and rational regulation of metabolite processes

would reduce labour costs and improve productivity;

Biotechnological Production of Lignans 143

5. Organic substances are extractable from callus cultures. Production by cell cultures

could be justified, for rare products that are costly and difficult to obtain through other

means.

Table 9.1. Podophyllotoxin and related lignans in plant in vitro cultures*.

Species In vitro culture Lignans synthesized

Callitris drummondii Callus, Suspension PTOX

Daphne odora Callus, Suspension Matairesinol, Lariciresinol, Pinoresinol,

Secoisolariciresinol, Wikstromol

Forsythia x intermedia Callus, Suspension Epipinoresinol

Forsythia x intermedia Callus, Suspension Matairesinol

Forsythia x intermedia Suspension Pinoresinol, Matairesinol

Forsythia sp. Callus, Suspension Matairesinol, Epipinoresinol, Phillyrin,

Arctigenin

Haplophyllum patavinum Callus Justicidin B, Diphyllin, Tuberculation,

Arctigenin

Ipomea cairica Callus Trachelogenin, Arctigenin

Ipomea cairica Callus Pinoresinol

Jamesoniella autumnalis Gametophyte 8, 8,2-Tricarboxy-5,4-dihydroxy-7

(5)-6-pyranonyl-7,8-

dihydronaphthalene and its two

monomethylesters

Juniperus chinensis Callus PTOX

Larix leptolepis Callus Pinoresinol; 2,3-dihydro-2-(4-hydroxy-

3-metoxyphenyl)-3-hydroxymethyl-5-

(-hydroxypropyl)-7-

metoxybenzofuran, Lariciresinol,

Secoisolariciresinol, Iso-lariciresinol

Linum album Suspension PTOX, 6MPTOX, DPTOX,

Pinoresinol, Matairesinol, Lariciresinol,

-peltatin, -peltatin

Linum altaicum Cell cultures Justicidin B, Isojusticidin B

Linum austriacum Callus, Suspension,

Root, Hairy root

Justicidin B, Isojusticidin B

Linum austriacum ssp.

euxinum

Cell cultures Justicidin B, Iisojusticidin B

Linum africanum Callus, Suspension PTOX, DPTOX

Linum campanulatum Callus, Suspension Justicidin B

Linum cariense Suspension 6MPTOX

5-demethoxy-6-

methoxypodophyllotoxin, and the

corresponding 8-epimers 6-

methoxypicropodophyllin, 5-

demethoxy-6-methoxypicropodophyllin

Linum flavum Root 6MPTOX

Linum flavum Suspension,

Embryogenic

Suspension

6MPTOX