AckermannTh. (ed) Wind Power in Power Systems

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

//INTEGRAS/KCG/P AGIN ATION/ WILEY /WPS /FINALS_1 4-12- 04/0470855088_ 10_CHA09 .3D – 181 – [169–196/28]

20.12.2004 9:27PM

by putting bids on the exchanges. The prices at the exchange Nord Pool actually set

the power price in the system.

(1)

.

Selling bids placed at the Nord Pool exchange or Elbas exchange: first, we have to

mention the price level. The price level is set by bids at both these exchanges. The

resulting prices are normally the prices defined by the units with the highest operating

costs. This means that the selling companies are paid the avoided cost of the most

expensive units. However, for wind power, the design of the exchange makes it

difficult to bid. The bids at Nord Pool have to be put in 12–36 hours in advance of

the physical delivery. This makes it almost impossible for wind power production to

put in bids, since the forecasts normally are too inaccurate for this time horizon. At

Elbas, the bids have to be put in at least 2 hours prior to physical delivery, therefore it

is also of little interest for wind power production to participate. At Nord Pool, the

prices are set at the price intersection of supply and demand . At Elbas, in contrast, the

bids are accepted as they are put in (i.e. there is no price intersection). These

exchanges will probably have to be changed if there is a future increase in the amount

of wind power produced.

The conclusion is that, in the current deregulated market, it may be difficult for wind

power to capture the income from the avoided costs of the most expensive units, as wind

power generation has, in comparison with other power sources, rather limited options of

actually trading in this market. From a physical point of view, the power system does

not need 12–36 hours of forecasts. This structure reduces the value of wind power, or

forces wind power generation to cooperate with competitors that are aware of the

reduced value of wind power in the current structure.

9.4.2 The market capacity credit of wind power

Historically, capacity credit ha s not been an important issue in Sweden since the system

LOLP has been very low. This was because the companies had to keep reserves for dry

years. These reserves actually had become so large that there were huge margins for

peak load situations. With deregulation, this has changed. Now the amount of reserves

has decreased, resulting in an increased interest in capacity credit.

In Sweden, new regulations were introduced on 1 November 1999 in order to handle

the risk of a capacity deficit in the system. Currently (2004), these regulations imply that

the TSO Svenska Kraftna

¨

t can increase the regulating market price to e670 per MWh

(about 20 times the normal price) in case there is a risk of a power deficit, and to e2200

per MWh if there is an actual power deficit. This method of handling the capacity

problem means that wind power generation may receive very high prices during situ-

ations where there is a risk of a capacity deficit. The reason is that traders that expect

customer demand to exceed the amount the traders have purchased have to pay e2200

per MWh for the deficit. This means that they are willing to pay up to e2200 per MWh

(1)

See Nord Pool, http://www.nordpool.no/.

Wind Power in Power Systems 181

//INTEGRAS/KCG/P AGIN ATION/ WILEY /WPS /FINALS_1 4-12- 04/0470855088_ 10_CHA09 .3D – 182 – [169–196/28]

20.12.2004 9:27PM

in order to avoid this cost. However, there are still problems related to the design of the

exchange and the required forecasts as discussed in Section 9.4.1.

9.4.3 The market control value of wind power

In Sweden, primary and secondary control are handled through the so-called balance

responsibility. The Electricity Act states that:

An electricity retailer may only deliver electricity at points of con nection where

somebody is economically responsible for ensuring that the same amount of

electricity that is taken out at the point of connection is supplied to the national

power system (balance responsibility).

This implies that someone has to take on the balance responsibility for each point with a

wind power plant – and the wind power owner has to pay for this. This means that

problems related to primary and secondary control are included in the market structure.

I am not aware of any detailed evaluation concerning whether these costs reflect the

‘true costs’ in the system. However, the TSO Svenska Kraftna

¨

t has to purchase any

additionally required dispatch from the market, which means that, at least, the suppliers

will be paid.

There may be problems regarding the competition in the so-called regulating market,

which corresponds to secondary control. A power system normally does not have so

much ‘extra’ reserve power, since the power system was dimensioned with ‘sufficient’

margins (i.e. very close to normal demand ). The owners of such regulating resources

tend to have little competition in cases when nearly all resources are needed. This means

that they can bid much higher than marginal cost, since the buyer of the reserves,

normally the TSO, has to buy, no matter what the price is. In a power system with

larger amounts of wind power, the requirement and use of reserve power will increase.

This means that, in a deregulated framework, there is a risk that profit maximisation in

companies with a significant share of available regulating power can drive up the price

for the regulation. This means that the price for regulating power that is needed to

balance wind power can increase, which means that the ‘integration cost’ of wind power

seems to be higher than the actual physical integration cost.

However, if competition is working, the daily control value wi ll be included in the

market, as the secondary control is used to handle the uncertainties. Again, the time

frame required by the bidding process is a problem (see Section 9.4.1).

The season al control value is included in the market since the prices change over the

year, corresponding mainly to a changed the hydro power situation.

9.4.3.1 Market multiyear control value

In this section, the impact of multiyear control on the value of wind power will be

illustrated with use of the example of the Nordic market, with its significant amount of

wind power. The prices in a hydro-dominated system will here be analysed in an

approximate way. The aim is to estimate an economic value of the yearly energy

production including the variations between different years.

182 The Value of Wind Power

//INTEGRAS/KCG/P AGIN ATION/ WILEY /WPS /FINALS_1 4-12- 04/0470855088_ 10_CHA09 .3D – 183 – [169–196/28]

20.12.2004 9:27PM

As in e very market, the prices on the power market decrease when there is a lot of

power offered to the market. This implies that during wet years the prices in the Nordic

market are significantly lower than during dry years. During a dry year, the prices are

much higher as a large amount of thermal power stations have to be started up in order

to compensate for the lack of water.

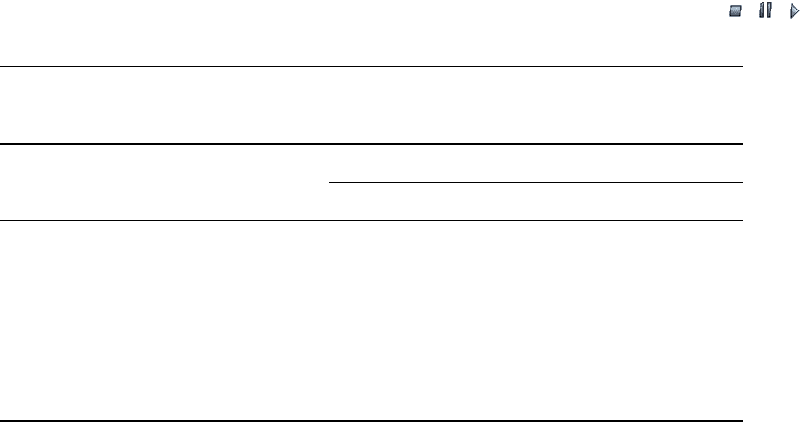

This means that the yearl y mean price, P

year

, can be approximated and described as a

function of the inflow x (calculated as yearly energy production). In order to be able to

analyse this from system statistics, the load changes between different years have to be

taken into account. The price does not depend directly on the hydro inflow but rather on

the amount of thermal power that is needed to supply the part of the load that is not

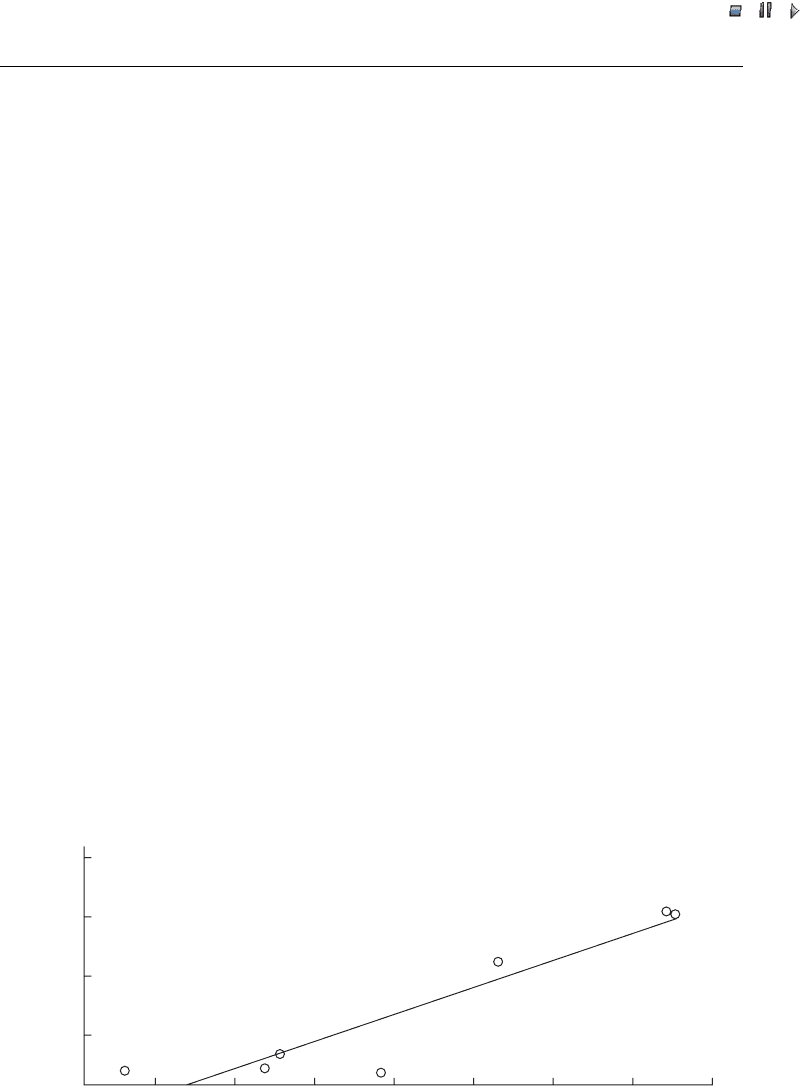

covered by hydro power. Figure 9.6 shows the yearly mean power price in Sweden as a

function of the required amount of thermal power (load inflow). In the figure, the

inflow is calculated as the sum of real hydro production and changes in reservoir

contents. The x-axis does not show the total thermal production, since the inflow is

used and not the hydropower production. The reason is as follows: the total reservoir

capacity is comparatively large (120 TWh) and this means that the stored amount of

water at the end of the year also influences the prices during the end of the year. If hydro

power production is exactly the same during two years, but during one these years the

content of the reservoir is rather small at the end of the year, the power price will be

higher during this year. It simply has to be higher, otherwise the water would be saved

for the next year.

A least square fit of the points in Figure 9.6 leads to:

P

year

¼ a

1

þ b

1

y; ð9:6Þ

where a

1

¼0:0165 and b

1

¼ 0:000251.

In the text below, it is easier to express the power price as a function of the inflow x.

For a given load level, D, the inflow can be calculated as

x ¼ D y: ð9:7Þ

Load – water inflow (TWh per year)

110 120 130 140 150 160 170 180

0.025

0.03

0.02

0.015

Price in Sweden (euro per kWh)

1998

2001

2000

2002

1997

1999

1996

P

year

= –0.0165 + 0.000251y

Figure 9.6 Yearly mean price as a function of total thermal production (for Sweden, Norway and

Finland)

Wind Power in Power Systems 183

//INTEGRAS/KCG/P AGIN ATION/ WILEY /WPS /FINALS_1 4-12- 04/0470855088_ 10_CHA09 .3D – 184 – [169–196/28]

20.12.2004 9:27PM

Equation (9.6) can now be rewritten as

P

year

¼ a

1

þ b

1

ðD xÞ¼ða

1

þ b

1

DÞb

1

x ¼ A þ Bx; ð9:8Þ

where

A ¼ a

1

þ b

1

D;

B ¼b

1

:

ð9:9Þ

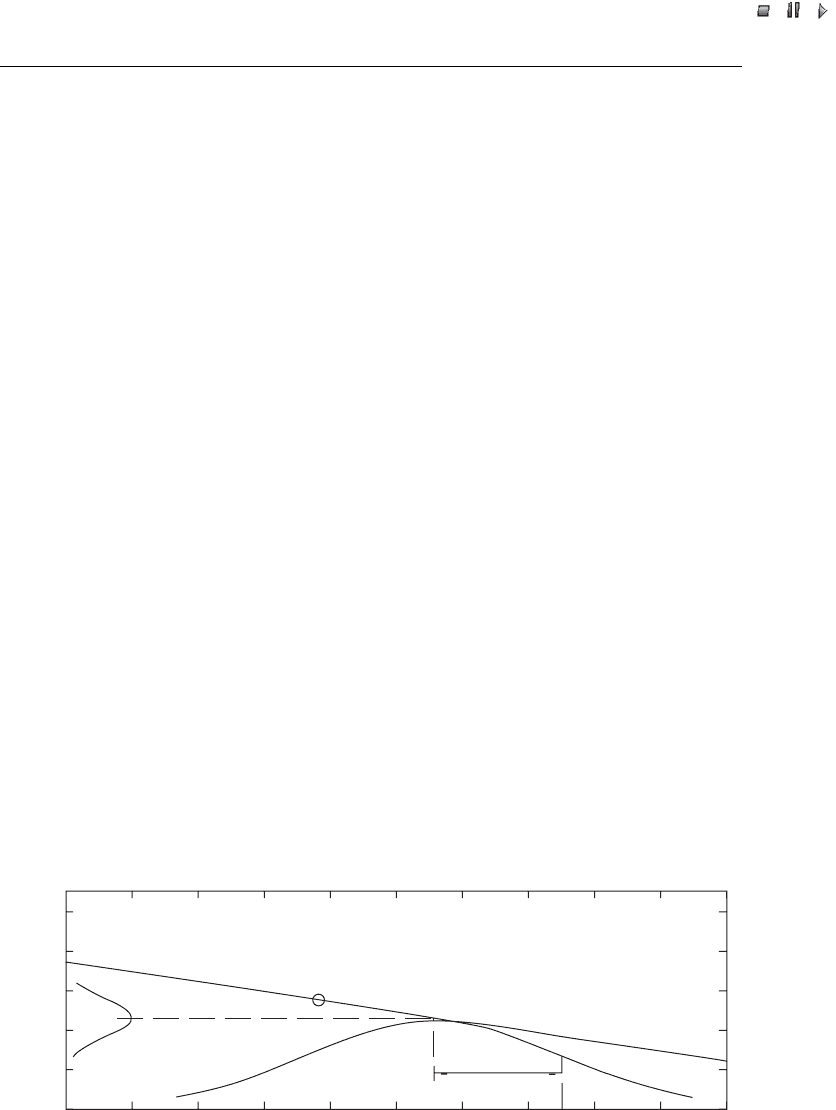

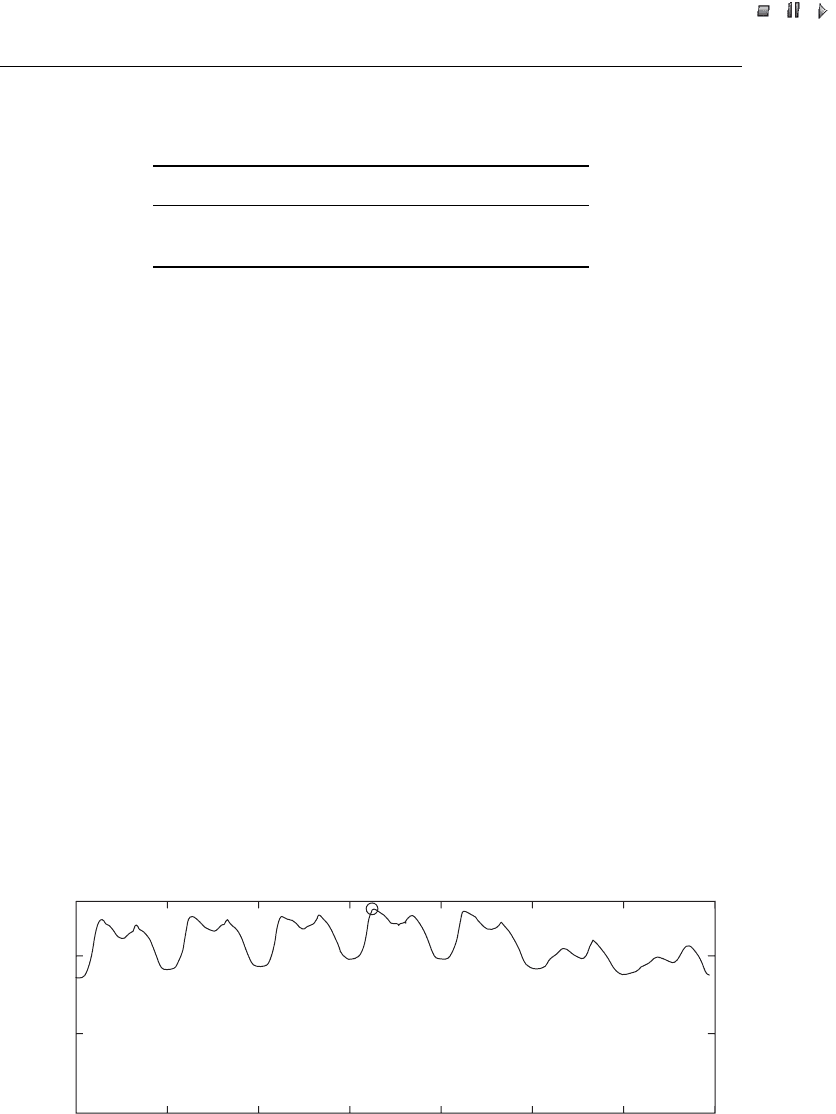

Figure 9.7 shows the price as a function of the inflow, P

year

(x). The parameters in

Equation (9.9) are then evaluated for a case with load figures from the year 2002 (i.e.

D ¼ 353 TWh).

The inflow varies between different years and can be approximated with a Gaussian

distribution with a mean value m

x

and a standard deviation

x

as shown in Figure 9.7.

Figure 9.7 shows the real case of Sweden, Norway and Finland with a normal inflow of

m

x

¼ 195 TWh. The applied standard deviation refers to the period 1985–2002, and the

result is

x

¼ 19:3 TWh. With the assumed linear relation between inflow and price, the

expected price, E(P

year

), and the standard deviation of the price, (P

year

), can be

calculated as follows :

EðP

year

Þ¼EðA þ BxÞ¼A þ Bm

x

;

ðP

year

Þ¼ðA þ BxÞ¼jBj

x

:

ð9:10Þ

The Gaussian distribution of the price is also shown in Figure 9.4. In this case, E(P

year

)

is e0.023 per kWh and the standard deviation is e0.0048 per kWh. The total value of the

inflow V

x

can be calculated as follows:

V

x

¼ P

year

x ¼ Ax þ Bx

2

: ð9:11Þ

140 150 160 170 180 190 200 210 220 230 240

0.05

0.04

0.03

0.02

0.01

0

E(P

year

)

P

year

= A + Bx

P

year

(euro per kWh)

x (TWh per year)

m

x

σ

x

2002

Figure 9.7 Yearly mean price as a function of inflow

184 The Value of Wind Power

//INTEGRAS/KCG/P AGIN ATION/ WILEY /WPS /FINALS_1 4-12- 04/0470855088_ 10_CHA09 .3D – 185 – [169–196/28]

20.12.2004 9:27PM

The expected value can therefore be calculated as:

EðV

x

Þ¼EðAx þ Bx

2

Þ

¼ Am

x

þ BEðx

2

Þ

¼ Am

x

þ Bð

2

x

þ m

2

x

Þ

¼ m

x

ðA þ Bm

x

ÞþB

2

x

< m

x

EðP

year

Þ;

ð9:12Þ

since B < 0. The formula shows that the expected value of the inflow is lower than the

mean inflow multiplied by the mean price. This is owing to the fact that high inflows

give lower prices for large volumes, and this is not compensated by the higher prices that

are paid during lower inflows.

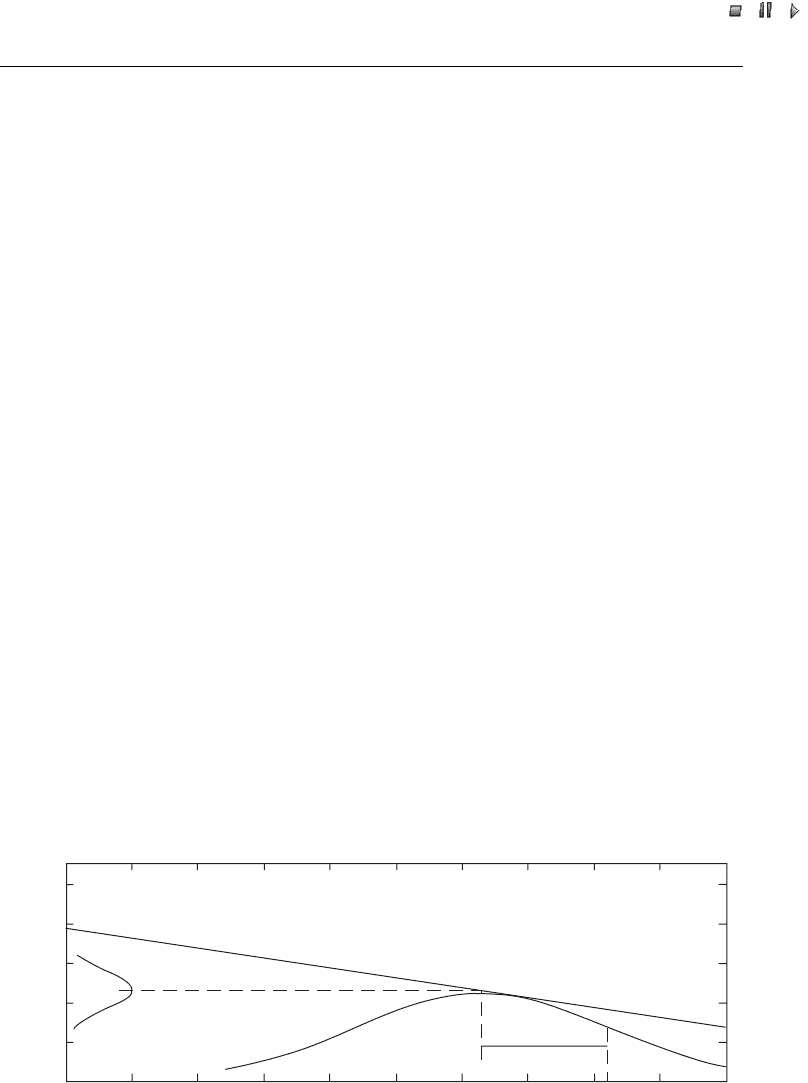

9.4.3.2 The value of a new power source

We now assume that a new power source is installed and produces m

y

TWh during a

normal year. It is also assumed that the new power source supplies an increased load

(or replaces old thermal plants) at the same yearly level as the mean production of the

new source (i.e. m

y

TWh). This implies that during a normal year, the price level will

be the same, independent of the new source and the increased load (see Figure 9.8).

This means that the new load and new power source will not affect the mean price level

in the system. With this assumption, the price function in Equation (9.8) has to be

rewritten as

P

0

year

¼ A

0

þ Bðx þ yÞ: ð9:13Þ

140 150 160 170 180 190 200 210 220 230 240

x (TWh per year)

0.05

0.04

0.03

0.02

0.01

0

P

year

(euro per kWh)

E(P ′

year

)

P

′

year

= A ′+Bx

m

x + y

σ

x + y

Figure 9.8 Yearly mean price as a function of inflow plus production in the new energy source

with a new load

Wind Power in Power Systems 185

//INTEGRAS/KCG/P AGIN ATION/ WILEY /WPS /FINALS_1 4-12- 04/0470855088_ 10_CHA09 .3D – 186 – [169–196/28]

20.12.2004 9:27PM

Only the A parameter is assumed to change, to A

0

. This implies that a decreased

production from hydro and new energy source of 7 TWh, for example, is assumed to

have the same effect on the price as reducing hyd ro production itself to a level of 7 TWh.

With these assumptions, the mean price shou ld still be the same; that is:

EðP

0

year

Þ¼A

0

þ Bðx þ yÞ¼EðP

year

Þ;

which implies

A

0

¼ A Bm

y

: ð9:14Þ

We now assume that the new power source is renewable with a low marginal cost. This

means that the yearly production is related to the amount of available primary energy:

sunshine, water, waves or wind. It is assumed here that the new renewable power source

cannot be stored from one year to the next. This implies that the value of existing hydro

power x plus the new source y is given by:

V

xþy

¼ A

0

ðx þ yÞþBðx þ yÞ

2

: ð9:15Þ

The new renewable power source has a mean value of m

y

, and a standar d deviation of

y

. There might also be a correlation between the yearly production of the new renew-

able source y and the existing hydro power x. The correlation coefficient is denoted

xy

.

The expected value for hydro plus the new power source becomes:

EðV

xþy

Þ¼EA

0

ðx þ yÞþBðx þ yÞ

2

hi

¼A

0

ðm

x

þ m

y

ÞþBð

2

x

þ m

2

x

ÞþBð

2

y

þ m

2

y

þ 2

xy

x

y

þ 2m

x

m

y

Þ:

ð9:16Þ

The expected incremental value of the new renewable source E(V

y

) can be estimated as

the difference between the expected value of hydro plus new renewable source [see

Equation (9.16)] y, and the expected value of only hydro power [see Equation (9.12)].

By app lying Equation (9.14), this value can be written as

EðV

y

Þ¼EðV

xþy

ÞEðV

x

Þ

¼ðA þ Bm

x

Þm

y

þ Bð

2

y

þ

xy

x

y

Þ: ð9:17Þ

We start by assuming the simple case where we have a constant new power source with

y

¼ 0. The value for this source is

EV

y

ð

y

¼ 0Þ

¼ðA þ Bm

x

Þm

y

¼ EðP

year

Þm

y

; ð9:18Þ

that is, the produced energy is sold (as a mean value) to the mean price in the system.

The next example includes a variation between different years, but this variation is

uncorrelated with the variation in the existing hydropower (

xy

¼ 0). Under these

circumstances, the value is given by

EV

y

ð

xy

¼ 0Þ

¼ EðP

year

Þm

y

þ B

2

y

; ð9:19Þ

186 The Value of Wind Power

//INTEGRAS/KCG/P AGIN ATION/ WILEY /WPS /FINALS_1 4-12- 04/0470855088_ 10_CHA09 .3D – 187 – [169–196/28]

20.12.2004 9:27PM

which is equal to that of the hydro power in Equation (9.12). The lowered value (B < 0)

depends on the fact that hydro together with the new power source, will vary more than

only hydro itself, and larger variations lower the value [see Equation (9.12)].

With a positive correlation,

xy

> 0, between the new source and existing hydro

power the value is even lower [see Equation (9.17)], where B < 0. This is owing to the

fact that a positive correlation implies that the new power source produces more during

wet years (with lower prices) than during dry years (with higher prices). If, however, the

correlation is negative the value is higher.

9.4.3.3 Numerical examples

Here, the method presented above will be applied to three examples: new thermal power

plants, new hydropower and new wind power. In all the three cases it is assumed that the

expected yearly production is 7 TWh and that the load also increases by 7 TWh per year.

The system studied is the Nordic system (i.e. Sweden, Norway and Finland the see data

in Figure 9.7). This means that during a hydrologically normal year, the expected power

price is E(P

year

) ¼ A þ Bm

x

¼ e0:0230 per kWh.

It is assumed here that a new thermal power plant will produce approximately the

same amount of power per year, independent of hydropower inflow. This means that the

operating cost of the plant is assumed to be rather low, because the amount of energy

production per year is assumed to be the same dur ing comparatively wet years, when the

power price is lower. With these assumptions, the expected value of this power plant

becomes, from Equation (9.18),

VðthermalÞ¼EðP

year

Þm

y

:

The value is

VðthermalÞ

m

y

¼ EðP

year

Þ¼e0:0230 per kWh:

Now, assume that new hydropower will be installed in Sweden. We assume that the

variations of new hydro power in Sweden will follow the same pattern as old hydro power.

This means that the standard deviation of 7 TWh of hydropower will be 0.895 TWh based

on real inflows for the period 1985–2002. The inflows are not exactly the same for the

Swedish and the Nordic system. The correlation coefficient is 0.890. With these assump-

tions, the expected value of hydropower becomes, from Equation (9.17),

VðhydroÞ¼EðP

year

Þm

y

þ Bð

2

y

þ

xy

x

y

Þ

¼ 0:023 7 0:000251ð0:895

2

þ 0:890 19:3 0 :895Þ¼0:1573:

The value is

VðhydroÞ

m

y

¼ e0:0225 per kWh:

Wind Power in Power Systems 187

//INTEGRAS/KCG/P AGIN ATION/ WILEY /WPS /FINALS_1 4-12- 04/0470855088_ 10_CHA09 .3D – 188 – [169–196/28]

20.12.2004 9:27PM

That is, the value of new hydro power is around 2.5 % lower than the value of

thermal power since more of the power production will be available during years with

lower prices.

The amount of wind power also varies between different years. For Sweden, available

hydropower and available wind power are correlated, as years with plenty of rain are

often also years with higher winds. The correlation depends on where the wind power

generation is located. In Sweden, hydropower is generated in the northern part of the

country. If the wind turbines are located a long distance from the hydro power stations,

the correlation is relatively low. In our example, the wind power is assumed to be spread

out over different locations. The standard deviation for total wind power is, for this

case, 0.7519 TWh (i.e. slightly lower than for hydro power). For the period 1961–1989,

the correlation between installed wind power and Swedish hydro power is 0.4022. It is

assumed here that the correlation between Swedish wind power and Nordic hydro

power is 0:4022 0:890 ¼ 0:358. With these assumptions, the expected value of wind

power, from Equation (9.17), is

VðwindÞ¼EðP

year

Þm

y

þ Bð

2

y

þ

xy

x

y

Þ

¼ 0:023 7 0:000251ð0:7519

2

þ 0:358 19:3 0:7519Þ¼0:1599:

The value is:

VðwindÞ

m

y

¼ e0:0228 per kWh:

That is, the value of new wind power is around 1 % lower than the value of thermal

power, but it is 2 % higher than the value for hydro power. This is owing to the fact that

wind power has a slightly negative correlation to the power price, as during years with

higher wind speeds prices are often lower.

9.4.4 The market loss reduction value of wind power

In Swedish deregulation, the grid companies levy tariff charges that include an energy

part, which is related to the losses. We will now take the example used in Section 9.3.4,

that is of 90 GWh of wind power on the Swedish island of Gotland, from the power

market view (for more details, see So

¨

der, 1999a).

In Sweden, the owners of wind power plants do not have to pay for increased losses

in the local grid, Gotland in this case. However, concerning the supplying grid, a local

grid owner has to pay the owners of wind power plants for the reduced tariff charges.

Since less power is transmitted from the mainland, these charges, which include costs

for losses, are reduced. In Table 9.3, the impact on the wind power owner is sum-

marised.

On the one hand, can be concluded that, in Sweden, the local grid owner is not paid

for the extra losses that wind power generation causes in the local grid. On the other

hand, the regional grid owner does not pay for the actual loss reduction caused by wind

power, since the tariffs are based on the mean cost of losses in the whole regional grid

and not on marginal losses of the specific costumer. The result is that wind power

188 The Value of Wind Power

//INTEGRAS/KCG/P AGIN ATION/ WILEY /WPS /FINALS_1 4-12- 04/0470855088_ 10_CHA09 .3D – 189 – [169–196/28]

20.12.2004 9:27PM

owners are paid less than the actual loss reduction. The ones that benefit from the

system are other consumers in the regional grid, but the consumers in the local grid will

have to pay higher tariffs because of the stipulation that wind power owners do not pay

for increased local losses.

9.4.5 The market grid investment value of wind power

In Swedish deregulation, the grid companies are paid with tariff charges. It is important

to ask whether these charges will be changed with the introduction of wind power. We

will use a numerical example to illustrate this issue (for more details regarding this

example, see So

¨

der, 1999a). In this example we analyse how the power charges in the

tariff for the supply of the Swedish island of Gotland could be reduced, depending on wind

power generation on Gotland. The Gotland grid company pays this charge to the regional

grid company on the mainland. The tariff of the regional grid includes the charges that the

regional grid has to pay to the national transmission grid, owned by the TSO Svenska

Kraftna

¨

t.

The basis for these calculations is therefore the tariff of the regional grid company,

Vattenfall Regionna

¨

t AB, concerning southern Sweden. The aim of this example is

mainly to illustrate how the calculations can be performed. The data are from 1997.

Table 9.4 shows the tariff for the mainland node where the island of Gotland is

connected. In Table 9.4:

.

yearly power is defined as the mean value of the two highest monthly demand values;

.

high load power is defined as the mean value of the two highest monthly demand

values during high load. High load is during weekdays between 06:00 and 22:00 hours

from January to March and No vember to December.

In relation to these two power levels, a subscription has to be signed in advance. If real

‘yearly power’ is higher than the subscribed value, an additional rate of 100 % becomes

Table 9.3 Market loss reduction value for 90 GWh wind power in Gotland

Grid True losses (GWh) Market treatment for wind power owner

loss (GWh) comment

Local grid 2.8 0 Grid-owner pays

Regional grid 4.6

o

3.7

o

Regional grid tariffs include

transmission grid losses, and these

tariffs are based on mean, not

marginal, losses

Transmission grid 2.8

Total 4.6 3.7 —

Wind Power in Power Systems 189

//INTEGRAS/KCG/P AGIN ATION/ WILEY /WPS /FINALS_1 4-12- 04/0470855088_ 10_CHA09 .3D – 190 – [169–196/28]

20.12.2004 9:27PM

payable for the excess power (i.e. a total of e6.9 per kW). If real ‘high load power’ exceeds

the subscribed value, an additional 50 % must be paid for the excess power (i.e. e12 per kW).

In addition , a monthly demand value can be calculated, which is the highest hourly

mean value during the month.

As just mentioned, the subscribed values have to be defined in advance. The real

power levels vary, of course, between different years. In the foll owing, we will describe

how the optimal subscribed values are estimated and give an example of how this level

changes when wind power is considered.

Before a year star ts the subscription levels for both the ‘yearly power’ and the ‘high

load power ’ have to be determ ined. We assume that both weeks with the dimensioning

load have a weekly variation according to Figure 9.9. Figure 9.9 shows only one week

but it is assumed that the other week in the other month ha s the same variation, but a

different weekly mean level.

The load curve we use refers to a week from Monday 01:00 to Sunday 24:00 hours. The

load is upscaled, and peak load during week 1 is 130 MW and during week 2 reaches

123.5 MW (i.e. it is 5 % lower). The following calculations are based on the assumption that

these two weeks contain the dimensioning hours for the two dimensioning months. The

peak load during both weeks is therefore on Thursday between 8:00 and 9:00 hours. These

two hours fall into the high load period. Therefore, the dimensioning hours for the ‘yearly

power’ and for the ‘high load power’ coincide. The mean value for these two occasions is

126.75 MW [i.e. 0:5 (130 þ 123:5)].

Statistics for several years have not been available for this study. Instead, it has been

assumed that the mean value of the two highest monthly values varies by 4%

Table 9.4 Subscription-based charges at the connection

point of Gotland

Charge (e/kW)

Yearly power charge 3.4

High load power charge 8

0

50

100

01234 657

Day

Week 1

MW

Figure 9.9 Hourly consumption during one week

190 The Value of Wind Power