A Practical Guide to Private Equity Transactions

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

57

Some common issues on deal structuring

A warrant is a security issued by a company which entitles the bearer to

subscribe for shares in that company at a pre-determined price. A warrant

instrument is entered into by Newco at completion of the transaction entitling

Newco to issue warrants, and then warrants are issued to the mezzanine funder

over an agreed number of shares at the then prevailing issue price (that is, the

price at which the managers subscribe for their sweet equity, or lower if pos-

sible). Accordingly, on exit, the mezzanine lender is able to exercise its war-

rants and participate in a proportion of the equity returns (typically, between 2

per cent and 5 per cent of the full equity value on exit). It is important to note

that the warrant is not a security or protection to the mezzanine funder – if the

company in question becomes insolvent, the right to own shares in it becomes

worthless. The warrant is only of value if there is a successful exit with value

for the equity. A warrant enables the mezzanine lender to balance risk over its

portfolio. The valuable shares it receives for the warrants on a successful exit

help to improve its overall return. It should also be noted that the warrant is

normally a permanent feature – it does not cease to exist if the mezzanine debt

is fully repaid.

The issues arising in the negotiation of mezzanine facilities and warrant

instruments are set out in more detail in chapter 6.

15

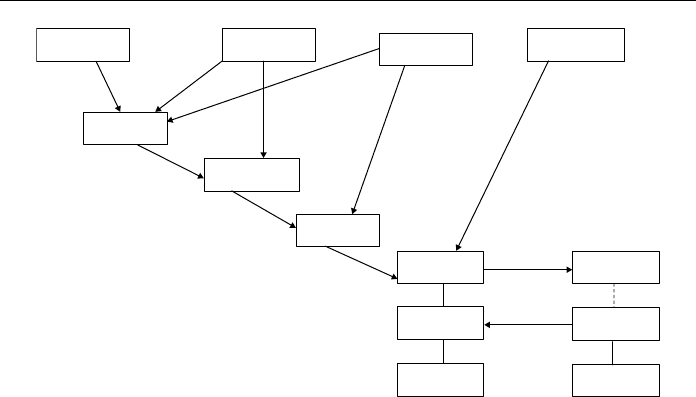

For the purposes of struc-

turing, however, it should be noted that, whilst the warrant will entitle the

mezzanine lender to subscribe for shares in the ultimate parent company along-

side the managers and the investor, for the reasons set out in section (b) above

a further Newco may sometimes be introduced into the transaction structure

which receives the debt funding, in order to achieve the appropriate structural

subordination. This is illustrated in Figure 3.4.

Chapter 6 also explains how other forms of junior debt came to promin-

ence in larger UK buyouts. In the economic and political climate existing at

the time of writing, such instruments are far less likely to be encountered.

Nevertheless, for the purposes of understanding any proposed deal structure,

the lawyer should identify each different layer of debt funding at the outset,

and clarify with any appropriate advisers (whether accounting, taxation or

legal) how many different new companies may need to be incorporated within

the structure to deal with those layers of debt.

3 Some common issues on deal structuring

3.1 Pricing the equity: the safe harbour

One overriding consideration in the structuring of the transaction will be a

desire on the part of the managers to ensure that any gains on their equity

investment fall within the capital gains tax, rather than income tax, regime. It

should also be borne in mind that a manager may be subject to an income tax

15 See chapter 6, section 4.2.

58

Transaction structures and deal documents

charge in the event that the manager acquires shares at a price which is less

than the market value of those shares on the date on which he acquires them.

These issues are considered in more detail in chapter 9, including the further

complexity arising as a result of the new rules concerning ‘restricted secur-

ities’ in the Income Tax (Earnings and Pensions) Act 2003,

16

and the require-

ments of the ‘safe harbour’ agreed between the BVCA and HMRC.

The safe harbour generally requires the managers and the investor to invest

at the same time, with the price paid by the investors for their equity shares

being no greater than the price paid by the managers for their equity shares

(in practice, the price paid for the equity is usually the same share for share).

Accordingly, the pricing of the equity on any transaction is usually a rela-

tively simple calculation once the commitment that the investor wishes to see

invested by the managers has been ascertained. The investor and managers

will simply pay the same price per percentage stake in the overall equity, and

the balance needed from the investor will be invested by way of loan notes.

The managers and the investor will therefore negotiate what is the appropriate

split of the equity based on the returns which the investor is expecting to obtain

by reference to the Business Plan.

17

There may, however, be commercial reasons for the various managers to

pay a different price for their percentage stake. For example, the investors may

wish to see wealthier or key managers committing substantial capital sums,

but be more sympathetic to those managers with limited nancial resources,

Sale of Shares

Payment of

Consideration

Midco 1

Midco 2

Target

Target

Senior

Debt

Loan Note

Investment

Share

Investment

Share

Investment

Topco

100%

owned

Mezzanine

Debt

Bidco

Subsidiaries

Subsidiaries

Seller(s)

Warrant

100%

owned

100%

owned

Investor

Mezzanine

Senior LenderManagers

Figure 3.4 Structural subordination (with mezzanine)

16 See chapter 9, sections 4.2 and 4.3.

17 In certain cases where there is a ratchet, the amount payable per share by a manager may be

greater than that payable by an investor: see chapter 9, section 4.4(c).

59

Some common issues on deal structuring

or who will play a less critical role in delivering the Business Plan. In those

situations, it is possible that loan notes or redeemable preference shares will

be introduced, to be subscribed for by those manager(s) required to pay a

higher price to reect the premium required over the cost per share paid by the

investor. Such instruments may rank either alongside or behind the investor

loan notes or preference shares. To satisfy the safe harbour requirements, how-

ever, any such instruments must carry a coupon which is no lower than any

other debt provider (including any bank).

18

This can prove particularly prob-

lematic on any transaction involving mezzanine debt, given the higher margin

charged by providers of such debt.

Issues around the safe harbour are not only of concern to the managers

and their advisers. The investor will usually be concerned to ensure that the

managers have the maximum likelihood of being subject to tax under the more

favourable capital gains tax regime, provided there is no material cost or incon-

venience to the investor, in order to ensure that managers are most effectively

motivated to achieve a favourable exit. Further, if income tax is payable, it may

well be Newco’s obligation to account for the same through PAYE, in which

case employees’ and employers’ NIC will also be payable – which is poten-

tially disadvantageous for the investor as a shareholder in Newco as the cost

will normally reduce the value of Target on the exit. Finally, many investors

look to motivate their own employees via a co-investment scheme or similar

arrangement, whereby the employees of the investor may have a direct nan-

cial interest in the equity of Newco via such scheme. Accordingly, depending

on exactly how such a scheme is structured, the individual employees at the

private equity rm may need to ensure that the relevant safe harbour require-

ments have been satised, and that appropriate joint elections

19

are entered

into, in respect of those investments. For all of these reasons, therefore, the

investor will typically ensure that appropriate advice is sought to conrm that

the proposed transaction structure does satisfy the safe harbour requirements.

3.2 Ratchets

In structuring any transaction, the parties will consider whether a ratchet

mechanism is appropriate. A ratchet is a mechanism which enables the man-

agers to participate in an increased share of the exit proceeds in the event that

an exit is ultimately achieved on more favourable terms.

20

Usually, the trigger

point at which the managers become entitled to a greater share of the exit pro-

ceeds is the target IRR which the investor is looking to achieve from its invest-

ment (so that, by way of example, an investor may say that the managers are

entitled to x per cent of the exit proceeds up to the point where those proceeds

18 This is another safe harbour requirement: see chapter 9, section 4.4.

19 Section 431 elections: see further chapter 9, section 4.3.

20 For details of how a ratchet is provided for in the relevant investment documentation, see

chapter 5, section 4.6.

60

Transaction structures and deal documents

give the investor an IRR of 35 per cent, but then the share will increase to y

per cent on any exit proceeds achieved beyond that point). A ‘dual test’ is often

incorporated, whereby the investor expects to achieve a minimum return as a

multiple of the initial investment (say twice money invested), as well as hitting

the target IRR, with the tipping-point being that exit value at which both of

these tests are rst satised.

Managers may nd the IRR concept difcult to understand,

21

and in

those circumstances the parties may feel that the ratchet will not have the

desired effect of motivating managers towards achieving a higher return for

the investor. Therefore, it is sometimes possible for a ratchet (particularly on

a smaller deal) to be structured on a more straightforward time and/or valu-

ation basis (for example, a ratchet will be triggered if an exit is achieved for a

value of greater than £x million within the next y years). However, it is more

common to see ratchets structured by reference to an IRR trigger, perhaps

combined with a separate money multiple threshold. Ultimately, these are the

performance measures by which the investor will be judged and rewarded, and

an IRR mechanism has the added advantage of taking into account all cash

ows to or from the investor during the life of the investment, thus avoiding the

need to revisit the relevant threshold in the event of follow-on investment.

Whilst a ratchet is often negotiated in terms of giving the managers more

if the relevant exit threshold is exceeded, the Memorandum of Understanding

between the BVCA and HMRC

22

originally stated that to fall within the safe

harbour the amount subscribed by the managers must reect the maximum

possible entitlement of the managers in respect of their equity shares. This

means that it has become more common to see ratchets which are dilutive or

negative in their effect (so, using the IRR example above, the managers may

begin with an equity share of y per cent, but this will then reduce pro rata to x

per cent in the event that the relevant threshold is not exceeded, rather than the

other way around). Where a ratchet is stated to operate in the more traditional

‘positive effect’ terms, then in order to ensure compliance with the safe har-

bour the managers may have to pay a premium on their equity when compared

with the investor, to reect the fully enhanced value, although there has been

more recent guidance on this point, as is explained in chapter 9.

As a result of these complexities, ratchets have been less common in trans-

actions since 2003. Many nancial advisers have concluded that it is better to

negotiate the overall split of the equity between the managers and the investor

to a rm number, than to have the uncertainty for all parties that the ratchet

may result in an unfortunate tax treatment. Further, even with an IRR ratchet

with carefully thought through multiple thresholds, the nancial performance

of the business may be such as to produce a distorted result for the managers

21 See chapter 1, section 3.4, for details of how an IRR is determined.

22 Section 6 of the MOU referred to in section 3.1 above. For more detail on the MOU, see chap-

ter 9, section 4.4.

61

Some common issues on deal structuring

(in situations of positive performance), or may soon become redundant as a

motivational tool (in cases of negative performance). However, ratchets are

still encountered, as they are often a helpful compromise where the investor

and the managers have differing views as to the likely future performance of

the business.

3.3 Multiple investors: understanding the parties

For simplicity, throughout this chapter we have made reference to a single

investor. However, in the vast majority of cases, there will be more than one

investor entity.

In smaller transactions, private equity funding may be provided by one sin-

gle private equity institution. However, the investments will almost invariably

come from a small number of investment funds managed by the private equity

house concerned. The main exception to this is those private equity houses

which are captives and invest from the parent entity’s own balance sheet.

23

Therefore, in the investment documentation it is usual to see a number of

different investing funds providing the appropriate equity and loan note invest-

ments on a pro rata basis. Often, these funds are structured as limited partner-

ships, registered under the Limited Partnership Act 1907. A limited partnership

will include one general partner (although there can be more than one, this is

rare in a private equity context), which is liable for all the debts and obligations

of the partnership.

24

The general partner will usually take the form of a lim-

ited company or, increasingly frequently, a limited liability partnership (LLP).

There will then be various limited partners who contribute capital as and when

required for investment, which might include pension funds, insurance com-

panies, local authorities and other national and international corporates. The

liability of these entities is limited to the amount contributed, provided they do

not participate in the management of the business of the fund.

25

Each private equity house will regularly undertake fundraising, to raise

monies for each new vintage of fund. Funds typically have an expected life

of around ten years, meaning that a successful UK private equity rm will

usually undertake a new fundraising exercise every three or four years. Each

vintage of fundraising may well include more than one limited partnership,

investing alongside each other. Often, this is in order that different limited

partnerships can be established by those partners sharing particular character-

istics – for example, it is common for American investors that are subject to the

requirements of ERISA to form a separate limited partnership vehicle so that

particular rights can be vested in that fund to qualify for ERISA.

26

23 See further chapter 1, section 2.3.

24 Section 4(2) of the Limited Partnership Act 1907.

25 Sections 4(2) and 6(1) of the Limited Partnership Act 1907.

26 Employee Retirement Income Security Act 1974, US legislation which imposes particular

requirements on certain types of US investor.

62

Transaction structures and deal documents

As noted in section 3.1 above, this investment by the various limited

partnerships may also be accompanied by an investment by a co-investment

scheme which invests on behalf of the individuals employed by that private

equity rm, and which will often invest only for a proportion of the equity

shares without the accompanying subscription for loan notes. Effectively, the

members of the investment team are subscribing for a proportion of ‘sweet

equity’ alongside the managers, in a proportion which the limited partners

have agreed is appropriate to ensure that they are sufciently motivated to

nd successful investment opportunities. The relevant individuals will benet

from the capital gains achieved on such shares, in addition to such individuals

beneting (to the extent they are stakeholders in the general partner) from the

management fees and carried interest payable to the general partner under the

limited partnership agreement.

It should be noted that not all private equity investors in the UK are struc-

tured as limited partnerships under the 1907 Act. Investors may be structured

as foreign partnerships, UK companies, venture capital trusts, investment

trusts or in a range of other forms based on the investor’s origins, and the tax

residence and status of the private equity rm and its underlying investors.

The investment documents will normally dene a ‘Lead Investor’; in a

limited partnership structure, this is more often than not the general partner

entity. That is the legal entity which will deal with day-to-day management

of the investment, including the giving or withholding of investor consents,

receipt of relevant information, appointment of investor directors, and so on.

It should also be noted that a limited partnership is not in itself a recognised

legal entity under English law, and as a result it is usual for a nominee com-

pany to be established to hold the relevant shares and loan notes on behalf of

the relevant funds.

In many transactions, private equity investors may well combine to form

a syndicate. Syndication is not exclusive to larger deals; a syndicate of inves-

tors is sometimes found in venture capital transactions, where investors look

to spread the higher risk associated with those types of investment. In those

cases, the structure may become more complicated to accommodate the spe-

cic requirements of each individual funder. At the very least, one would

expect to see far more detailed terms regarding the extent to which each mem-

ber of the syndicate has a right to consent to and/or veto any particular investor

consent. As an alternative, an initial investor may wish to reserve a right to

syndicate some or all of its investment post-completion, which would need to

be accommodated within the initial transaction documents.

Similarly, in larger transactions, one will often be confronted with a syndi-

cate of senior lenders, or an initial senior lender may look to syndicate its debt

investment following completion of the transaction.

27

27 See further chapter 6, section 3.4.

63

Some common issues on deal structuring

3.4 Investor/management fees

Any private equity investor will look to charge the relevant investee company

a fee for arranging its investment. This is in addition to any ongoing monitor-

ing fee, or other fee payable for the ongoing services of any appointed investor

director(s). The private equity investor will also expect the investee company to

pay any professional fees incurred by the private equity house in relation to the

transaction, including accountancy and legal fees, and other due diligence costs.

Prior to October 2008, the payment of such fees attracted a great deal of

attention amongst lawyers on the question of whether the same might constitute

unlawful nancial assistance for the purposes of the Companies Act 1985.

28

In

principle, it was possible that the payment by a company of fees incurred by a

party for the purpose of subscribing for shares in a company might constitute

nancial assistance – whilst it is more common to consider the question of

nancial assistance in the context of the acquisition by a party of shares from

another, it might have been argued that a subscription for new shares can consti-

tute an acquisition of shares for the purposes of section 151 of the 1985 Act.

As a result of these concerns, the BVCA has on separate occasions taken

advice from counsel as to whether any arrangement to pay such fees is unlaw-

ful. These concerns increased as a consequence of the Court of Appeal deci-

sion in Chaston v. SWP Group plc,

29

in which Arden LJ suggested a relatively

strict ‘but for’ approach for determining whether nancial assistance has

occurred. Since the abolition of nancial assistance for private companies with

effect from 1 October 2008, however, most of such analysis is now redundant

(although still available on the BVCA’s website for subscribing members). Such

issues may still be of relevance in the event that any transactions entered into

prior to that date are challenged in the future. It is also relevant if for some

other reason a public limited company is used as the Newco; this is very rare.

A related point, however, which remains of concern is whether any of such

fee arrangements might constitute a breach of section 580 of the Companies

Act 2006, which prohibits the issue of any company’s shares at a discount to

their nominal value. In advising the BVCA on the nancial assistance issues,

counsel also highlighted that, where an investor subscribes for shares at par

value, and the investee company then pays fees connected to such subscription,

it might be argued that such shares have been issued at a discount in contra-

vention of that section.

There are two steps which might be taken by the diligent legal adviser to

a private equity investor to deal with this issue. First, the relevant fees may

be invoiced to a company below the ultimate holding company in the rele-

vant structure. Whilst such an approach would not have addressed the nan-

cial assistance issues (as nancial assistance by a subsidiary for its ultimate

28 Companies Act 1985, sections 151 et seq.

29 [2002] EWCA Civ 1999.

64

Transaction structures and deal documents

holding company was also prohibited),

30

it should be sufcient to demonstrate

that such payment cannot be treated as a discount for the share subscription

if payment comes from a separate legal entity within the group. Alternatively,

where the ultimate parent company must pay the fees for whatever reason, then

those fees payable in connection with the equity investment may be identied

separately from those fees invoiced in connection with any loan investments,

or due diligence or other acquisition advice. The share capital in that parent

company is then issued incorporating a share premium which is sufcient to

satisfy the full amount of such fees (i.e. so that such deduction cannot in any

event be of such an amount which results in the shares being offered at a dis-

count). To be successful in this approach, it follows that the share premium

created must exceed the aggregate amount of fees payable to or on behalf of a

particular shareholder, which can be difcult when deals are structured with a

relatively low equity subscription amount.

3.5 Secondary buyouts and other ‘rollover’ sellers

There are often circumstances where an existing shareholder in Target will

become an investor in the acquiring Newco (or, in a multiple group structure,

the ultimate holding company). Common examples include a secondary buy-

out (discussed in more detail in chapter 12), and development capital transac-

tions where a founder may remain alongside the private equity investor (either

with or without extracting some value in cash as part of the transaction).

In these cases, the structure will need to accommodate the relevant seller tak-

ing the relevant loan and equity stake in Newco. The simplest way to achieve this

is by the buyer simply issuing consideration loan notes or consideration shares.

However, this will not work where the funding structure involves multiple Newcos,

as the buyer company will not be the company where that seller will be expected to

hold his equity interests, and possibly his loan note interests, going forward.

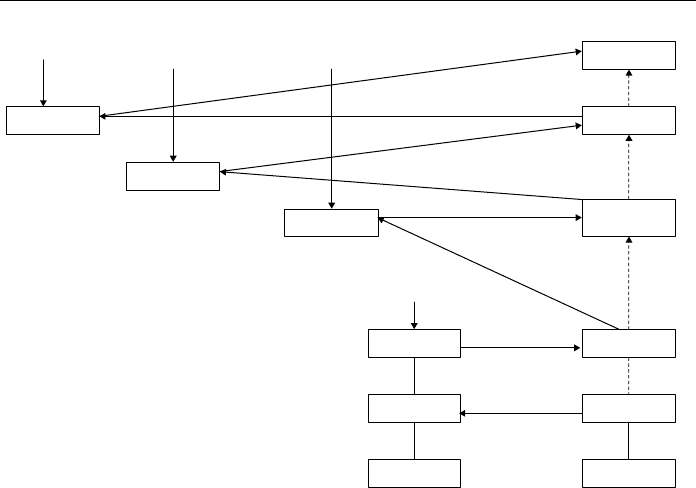

In those cases, the solution is usually for the buyer Newco (i.e. Bidco) to

issue loan notes to the relevant seller(s) as part of their consideration for the sale

of shares. A series of documents are then entered into by which the relevant

seller agrees to exchange his loan notes in Bidco for loan notes in that Bidco’s

holding company. If required, subsequent exchanges of loan notes may then

continue up the chain of companies (often referred to as a ‘ip up’) until such

point as the investment is in the correct entity. As a nal step, the relevant pro-

portion of loan notes will then be exchanged for shares in Topco, leaving the

seller with equity shares in the correct entity. This is illustrated in Figure 3.5.

Whilst it is possible for Topco to issue shares in consideration for the sale of

the shares to Bidco (and for Bidco to agree to procure such share issue within

the sale documentation, or even for Topco to be a party to the relevant sale

30 Section 151(1) stated that it was not lawful for a company or any of its subsidiaries to give

nancial assistance directly or indirectly for the purpose of that acquisition.

65

The deal documents

agreement for that purpose) to avoid the need for numerous ‘ip up’ documents,

this approach is not usually followed. One key reason for this is that the relevant

seller will usually want to roll over any capital gains in the existing shares into

the new investment, which requires the ‘ip up’ approach to be taken, and with

particular care to ensure that the relevant legislative requirements are satised.

In any transaction where one or more sellers are rolling part of their consid-

eration into the new investment vehicle, such a seller may try to negotiate that

such investment should be on like terms to the investor. That seller might argue

that the proportion of the total amount which is invested in the form of equity

rather than loan notes should be in the same proportion as is the case for the

institutional strip. Taking these arguments further, it might be possible for such

rollover shares to be free from some of the punitive restrictions (such as leaver

provisions) which attach to the sweet equity. Such participation in the institu-

tional strip might also stand alongside a separate subscription for sweet equity,

subject to the same terms and restrictions as the other managers, where the rele-

vant seller is also a key member of the management team going forward (as in a

secondary buyout). These issues are discussed in more detail in chapter 12.

4 The deal documents

The chapters that follow discuss the key points to be negotiated on the princi-

pal legal documentation on a UK private equity transaction. Whilst the precise

Issue of Topco Shares

Shareholders

Shareholder

Debt

Mezzanine

Debt

Seller(s)

Seller(s)

Seller(s)

Seller(s)

Target

Subsidiary

Topco

Midco 1

Midco 2

Subsidiary

Target

Bidco

Flip Up 2

Flip Up 3

Flip Up 1

Cash

consideration plus

Bidco Loan Notes

Sale of part of Midco 1 Loan Notes

Issue of Midco 1 Loan Notes

Issue of Midco 2 Loan Notes

Sale of Bidco Loan Notes

Sale of Midco 2 Loan Notes

Sale of Shares

Senior Debt

Figure 3.5 ‘Flip up’

66

Transaction structures and deal documents

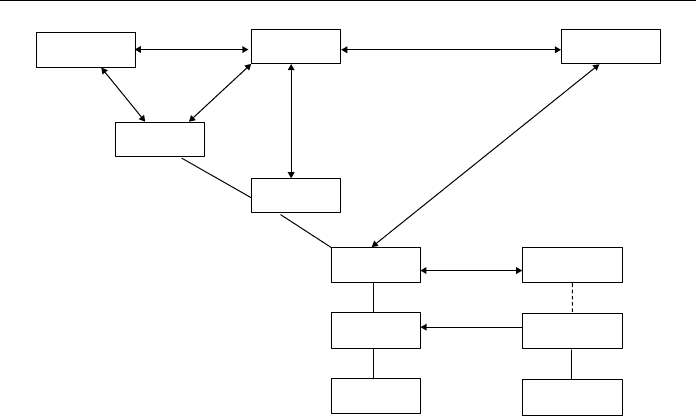

documentation required will vary depending on the nature and structure of the

particular transaction, Figure 3.6 is included here as it shows (by reference to

a simple deal structure diagram) the relationships that are governed by those

principal documents. A brief overview of the documents in each category is

provided below.

4.1 The acquisition documents

The documents governing the acquisition by Bidco of the Target, include:

the acquisition agreement, entered into by the seller(s) of the Target and •

Bidco, and possibly other parties (for example, in the case of a disposal by a

corporate group of a subsidiary, a guarantee may be required by Bidco from

the parent company);

a separate tax deed (although the tax provisions may alternatively be included •

within a tax schedule in the acquisition agreement);

the disclosure letter from the seller(s) of Target to Bidco, qualifying the war-•

ranties set out in the acquisition agreement;

stock transfer forms in favour of Bidco for the shares in Target, together with •

any ancillary transfer documents or agreements required for the transfer of

any assets not covered by the acquisition agreement (for example, to assign

assets held by an individual seller personally but used in the business);

any commercial agreements required to be entered into by such parties to •

facilitate the continued running of the business (for example, concerning

interim accounting, IT or other services to be provided for an initial period

from completion);

Midco

Target

Target

Acquisition

Agreement,

Disclosure Letter

and Ancillaries

Senior LenderInvestors

Managers

Loan

Notes

Investment

Agreement and

Articles

Topco

Intercreditor Agreement

Bidco

Subsidiaries

Subsidiaries

Seller(s)

Facilities Agreement

Security (with other

Group Companies)

Figure 3.6 Key transaction documents