Yasur-Lau Assaf. Household Archaeology in Ancient Israel and Beyond

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

42 nimrod marom and sharon zuckerman

each consisting of several rooms or courtyards. A possible open area

was discerned between these structures. e whole area was residential

in nature. Characteristic of this phase are the sealed entryways and the

blocked openings discerned in the walls. is phase is attributed, on

the basis of its rich ceramic assemblage, to the last phase of the LBII

city of Hazor (i.e., stratum 1A in the stratigraphic scheme of Yadin)

(Zuckerman 2008).

Area S is thus an ideal candidate for the reconstruction of the devel-

opment of a domestic quarter within the context of the Canaanite city.

e project was designed as an interdisciplinary endeavor, aiming to

extract as much data as possible from the excavated structures and

associated open areas. During excavation, special emphasis was put on

the maximum retrieval of archaeological material. Floor deposits were

wet sieved using a otation machine, while other less secure depos-

its were sampled by partial dry sieving. e preliminary goal of the

excavation is the recovery of several categories of data that will be

crucial for the achievement of the research objectives. ese include

larger samples of well-stratied artifacts, such as ceramics, lithics, ani-

mal bones, and plant remains, all of which are deemed necessary for

determining the nature and scale of various daily activities, as well

as assessing their spatial distribution and temporal development. e

faunal assemblage is of prime importance in this context, and special

emphasis was therefore placed on understanding its formation pro-

cesses and taphonomic history.

Research Questions and Premises

Bone deposition can be divided into primary, secondary, and tertiary

episodes (Schier 1972, 1976, 1983; Meadow 1978). Primary deposi-

tion of bone reects refuse discarded at the place of animal processing

and consumption, and thereby provides the highest resolution infor-

mation on domestic activity areas. Animal bones in primary deposi-

tion are usually very small fragments, likely to have been trodden into

earthen oors or otherwise to have escaped periodic cleaning (Flad-

mark 1982; Schier 1987; LaMotta and Schier 1999). is fraction

of the bone assemblage cannot be recovered without high-resolution

recovery methods, such as wet sieving (James 1997). e density of

very small bone splinters and chips inside domestic spaces is expected

to vary, as places in which cooking and other bone processing activities

a case study from the lower city of hazor 43

took place should exhibit a higher density of such debitage (Hull 1987;

Metcalfe and Heath 1990; Bartram et al. 1991). e number of burnt

specimens can indicate the consumption of roasted vs. boiled esh

(Speth 2000), and the size and frequency of cancellous bone fragments

may likewise indicate bone fats (grease) rendering in particular areas

(Outram 2001).

However, since most identiable bone fragments are large (epiphy-

ses, teeth, large long-bone sha fragments), and may prove a sani-

tary disturbance and a hindrance to movement inside domestic space,

they cannot be assumed to be found in primary depositional contexts

(LaMotta and Schier 1999). Ethnoarchaeological and archaeological

studies conducted on refuse management show that larger bone frag-

ments are routinely removed from household oors to either the area

immediately adjacent to the house (the “to”) or to central dumps,

which are usually located near the primary consumption area (e.g.,

Hayden and Cannon 1983; Bartram et al. 1991; Martin and Russel

2000). Animal bones in secondary deposition are probably the best

target population to investigate domestic subsistence practices. Com-

munal dumps and bones recovered from to areas (alleys, accumu-

lations between house walls) present time-averaged “samples” of the

subsistence activities carried out in a domestic area, and are thus of

prime importance to the derivation of species, skeleton element abun-

dance, and demographic data. Being larger and less fragmented, bones

in secondary deposition are generally the specimens that yield more

zooarchaeological data (morphological, taxonomical, anatomical, and

mensural), which can be brought to bear on questions regarding socio-

economic variability between occupation periods (Hesse 1986; Zeder

1988; Bar-Oz et al. 2007).

Bones in tertiary deposition are accumulations brought as construc-

tion material (mudbricks or lls) to their archaeological context, or

otherwise removed from their original location. ese bone remains

are of little value to faunal analysis, as their original spatial and tem-

poral provenance is not known.

Providing we accept the premise that houses were routinely cleaned

when occupied, large bone fragments found above and on house oors

may reect primary discard from post-abandonment use of a build-

ing by human or animal visitors (squatters). Alternatively, house

oor assemblages may reect post-abandonment use of a house as a

dump—in which case they are assumed to be constituted of secondary

deposition from nearby houses (Cameron and Tomka 1993; LaMotta

44 nimrod marom and sharon zuckerman

and Schier 1999). A criterion for dierentiating use of abandoned

houses as a communal dump from a squatter community may be the

comparison of the above-oor and oor deposits from a house to

known dumps and middens in the vicinity, especially in terms of spe-

cies and body-part diversity (i.e., the number of taxa represented in

the assemblages). Deposition by squatters would probably show fewer

(if any) specimens from exotic or imported taxa (e.g., Nilotic sh), and

an overall lower diversity than a time-averaged accumulation of food

refuse from part of a large urban center. Use of an abandoned house as

a dump in an active urban area would show a pattern similar to nearby

middens in terms of animal diversity and taphonomic signature. e

microfaunal assemblage may also hint at which of the two options is

likely to be true: many noncommensal microvertebrate remains may

indicate deposition to have been the result of post-abandonment use

of a house by squatters; presence of commensals (e.g., house mice,

Mus musculus domesticus) may indicate continued human presence

at the house’s vicinity and thus the use of an empty house as a dump

(see, also, Hesse 1978, 1979; Hesse and Wapnish 1985). Microfaunal

remains can also yield important environmental information. Since

these animals have limited ranges and specic habitat preferences,

they are ne indicators of the immediate environment of the archaeo-

logical context in which they were found (e.g., Piper and O’Connor

2001; Weissbrod et al. 2005).

A primary research question is which taxa and of what age and sex

groups were eaten by the residents of the domestic quarters; which

body parts were consumed most oen; and how these foodways varied

spatially and diachronically. Demography and anatomical representa-

tion of the various livestock taxa are considered means to reconstruct-

ing ancient economy (Payne 1973; Redding 1981; Zeder and Hesse

2000; Vigne and Helmer 2007). Diachronic or spatial uctuations in

the frequencies of gourmet (i.e., meat-bearing) vs. non-meat-bearing

portions of livestock taxa may indicate changes in auence (Crabtree

1990; e.g., Schulz and Gust 1983; Jzereef 1988; Schmitt and Lupo 2008;

Marom et al. in press). Demographic shis from a young adult male

dominated assemblage to one in which older animals and especially

more females are represented may denote changes toward a less con-

sumerist and more autarkic economy, indicating a regional socioeco-

nomic shi toward lesser integration. An increase in the proportions

of livestock animals over game and low variability in the demographic

parameters of the population and skeleton element representation

a case study from the lower city of hazor 45

indicate consumers in the distribution chain of animal products, and

thus higher socioeconomic status (Zeder 1991). Trade relations can

be partly reconstructed using the presence of nonlocal animals in the

faunal assemblage (Van Neer and Ervynck 2004; van Neer et al. 2004;

Raban-Gerstel et al. 2008). ese imported animal commodities can

also serve as a measure of wealth: imported goods are usually limited

to the auent (Ervynck et al. 2003; Veen 2003).

Another important research question is diachronic and spatial pat-

terning in butchery practices of dierent taxa. Intensive butchery,

which includes the utilization of bone marrow and even grease, indi-

cates heightened eorts to utilize bone fats (Outram 2001). Utiliza-

tion of a wider selection of skeleton elements, especially those poor

in esh (feet, heads), may indicate subsistence stress or low socioeco-

nomic status (Schulz and Gust 1983; Izjereef 1989). Such information

can be derived from bones in secondary deposition (for interstrata

comparisons) and, to a lesser degree, from bones in primary deposi-

tion (for interhousehold comparisons; see below). Butchery patterns as

evident by cut marks on bone surfaces can illuminate dierential treat-

ment of carcasses from dierent animals (Lyman 1994; Lyman 2005),

as well as the intensity of consumption of various animal portions

(Domínguez-Rodrigo 1999). Inter- and intrastrata changes in butch-

ery intensity may be good indicators of auence. As primary animal

products (meat) become scarce, butchery would intensify to extract

animal fat from bone marrow (Bar-Oz and Munro 2007) and even

grease (Outram 2001, 2003)—practices which require some eort.

Also, a greater diversity of animal portions from more locally avail-

able taxa, including wild game and fowl, would probably be present at

the assemblage (Zeder 1988).

e sex and age distribution of the animals represented at the site

can be used to test specic hypotheses (Marom and Bar-Oz 2009)

regarding ancient herd management strategies. Such strategies include

optimization of culling to increase work, caloric, or wool yields from

domestic ocks providing animal products to the site (e.g., Payne

1973; Redding 1981).

e picture of past foodways gained by zooarchaeologists is greatly

biased by deposition and post-depositional loss of information

brought about by various taphonomic agents (Lyman 1994; Reitz and

Wing 1999). ese include, for example, the deleterious eects of bone

fragmentation by humans (Brooks et al. 1977; Marshall and Pilgram

1991; Enloe 1993; Pickering and Egeland 2006; Bar-Oz and Munro

46 nimrod marom and sharon zuckerman

2007), carnivore gnawing (Binford 1981; Lyman 1994; Blumenchine

et al. 1996), subaerial weathering (Behrensmeyer 1978), and trampling

(Olsen and Shipman 1988). Another goal of faunal analysis is reveal-

ing to what degree various taphonomic actors aected the assemblage,

and thus how reliable cultural inferences based on faunal data is (Bar-

Oz and Munro 2004). Of equal importance is the determination of the

bias caused by bone recovery and analysis procedures (James 1997;

Marean et al. 2004). is problem is exacerbated in large-scale excava-

tions, where the recovery of all faunal material is not practical.

On-Site Faunal Recovery Procedures: A Case Study from Hazor

e recovery of faunal remains from large urban sites is problematic,

since practical limitations prohibit the complete recovery of all bone

material. erefore, at Hazor a two-tier recovery system is used to col-

lect bone specimens. e rst tier consists of recovery by hand by the

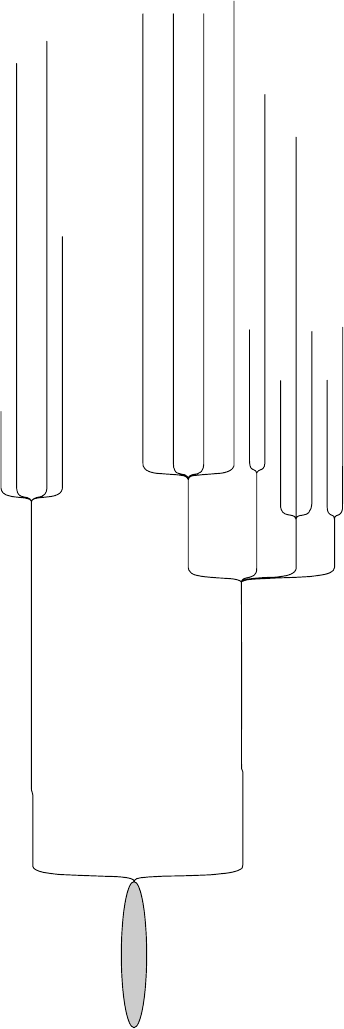

excavators; and the second of wet sieving (Fig. 3).

Recovery of faunal remains by the excavators without sieving was

shown to be a serious source of bias (Meadow 1980; Turner 1989;

James 1997; Zohar and Belmaker 2005). To reduce this bias, the hand-

picked sample is used to derive zooarchaeological information per-

taining only to larger mammals: sheep, goats, pigs, cows, and larger

game animals, the bones of which are more massive and likelier to be

picked up by excavators.

Wet sieving was carried out using a 1 mm aperture mesh. e buck-

ets for wet sieving contained sediments from which no bone mate-

rial was extracted by the excavators. Following sieving and drying, the

sieved fraction was sorted to isolate micromammal, sh, and mam-

mal bones. e samples for wet sieving were taken daily, in vertical

intervals of approximately 10 cm. When digging through extensive

lls, mudbrick collapse, or topsoil, ve buckets were sampled from

each square. e horizontal pattern of sampling alternated daily

between an X-shaped pattern, where one bucket is lled from each

corner of the square and one from its center, and a cross-shaped pat-

tern where four buckets were lled from the mid-side of the excava-

tion square and an additional bucket was taken from its center. is

superimposition of an X and a cross formed a “Union Jack” pattern

of sampling in each square, thereby making an allowance for spa-

tial variability in nds’ density and composition, while keeping the

a case study from the lower city of hazor 47

Figure 3. A owchart presenting a scheme of the faunal analysis procedures employed at the Lower City of Tel Hazor. See text

for explanations.

Fossil assemblage sampling using...

Recovery by hand

Context: Secondary

Analytical methods: Diagnostic zones, bone surface modications

Derived information: Herd demography, body-part representation, taxonomic frequencies, butchery, taphonomy

Researchquestions: Social status and identity, gross diachronic and spatial trends in taxonomic, demographic and

anatomical parameters

Recovery by wet sieving

Recovery level: Lo

w, mainly medium and large mammal bones

Recovery level: High, representative sample of...

Bird remains

Fish remains

Research question: Trade and dietary spectrum

Research question: Fowling, dietary spectrum

Derived information: taxonomic frequencies, body-part representation, taphonomic observations

Context: Primary and secondary

Context: Primary and secondary

Micro-vertebrate remains

Research question: Depositional context of th

e associated faunal assemblage, micro-environment

Context: mainly primary deposition

Macro-mammal remains

Research questions: High resolution contextual comparisons; activity areas; control over recovery and anatical biases in

the hand-recovered sample

Context: Small fragments on oor levels may be in primary deposition

Derived informaton: Size-class (caprine/cattle size) and rough body part (limb, he

ad, axis) relative frequency

determinations per contextual unit; Density of bone nds of each type per volume unit.

Analytical methods: Identication to rough taxonomic and body-part categories of ALL bone fragments from wet-sieving;

nds’ density estimations; some taphonomic observations

48 nimrod marom and sharon zuckerman

wet sieving and consequent sorting of the sieved material logistically

manageable (Fig. 4). When the excavation reached above oor lev-

els, the sampling method changed to include a varying number of

buckets from each locus per 10 cm vertical increment. e samples

were taken to provide a balanced horizontal representation of all

parts of each of the sampled loci. Mean heights were taken for each

sampling unit, and the volume of sediment (in liters, before sieving)

was recorded.

Zooarchaeological Analytical Procedures

Processing the hand-picked sample includes the identication of cer-

tain skeleton elements, known as “diagnostic zones,” following the

protocol detailed by Davis (1992). ese zones are easily ascribed to

taxon and element, and provide the basic set of aging data through

teeth eruption and wear (Grant 1982), and state of epiphyseal fusion

(Silver 1969). Measurements of these elements are later used for

determining the sex ratios in the archaeological sample (e.g., Wilson

et al. 1982; Greeneld 2006). e cost-eciency of using diagnostic

zones is high, and it enables the derivation of maximal zooarchaeolog-

ical information in a short time. Diagnostic zones are additive values

that represent real counts, which makes them amenable to statistical

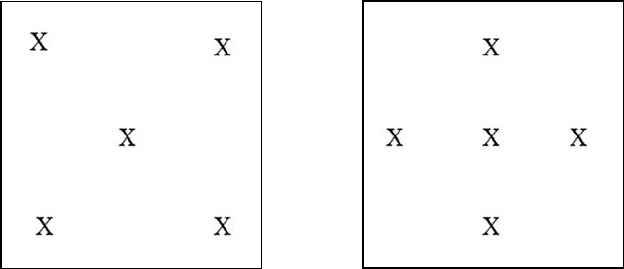

Figure 4. e sampling scheme for wet sieving above oor levels. X marks

a bucketful of sediments from which bone material was not removed by the

excavators in a 5 m × 5 m excavation square. e sampling scheme alter-

nates between the St. Andrew’s cross (le) and the St. George cross (right) in

10–15 cm vertical increments.

a case study from the lower city of hazor 49

analyses of frequencies, and free from problems of aggregation (unlike

minimum number of individuals/elements counts) (Grayson 1984;

Lyman 2008). In addition, diagnostic zones are small and far apart on

the skeleton, which allows the assumption of independence of counts,

necessary to analyses of frequencies, slightly easier to make.

Although cost-ecient, the diagnostic zones methods have been

criticized in the last decade for being liable to biases stemming from

density-mediated attritional processes (Marean and Frey 1997; Picker-

ing et al. 2003; Marean et al. 2004). However, empirical studies con-

ducted in later prehistoric sites (Bar-Oz and Dayan 2002; Marom and

Bar-Oz 2007) have shown the dierence between the various analytical

methods to be small. Recent studies at Tel Rehov (Marom et al. 2009)

showed a high frequencies of high-value, low-density bones, in spite

of the density-mediated attrition that was demonstrated to have taken

place at the site. A similar study of skeleton element abundance at Tel

Dor (Raban-Gerstel et al. 2008) showed similar underrepresentation

of heads and feet, which is contrary to the prediction of the “sha-

critique” for a site where consistent recovery and analysis of long-bone

sha fragments did not take place.

Processing the wet-sieved sample units includes picking through the

sieved sediments to isolate micromammal and sh bones, which are

passed on to respective experts aer their broad taxonomic designation

was recorded. All larger mammal bones are separated and counted to

calculate nds’ density per sample. Mammal bones are then sorted into

a “large mammal” (cow/horse-sized) and “medium mammal” (sheep/

goat-sized) categories, and further into long bone, axial, and cranial

fragments. e number of burnt bones is also recorded (Table 1).

e number of head, limb, and axis skeleton bones in the sieved

sample can be contrasted with the skeleton element breakdown

derived from the analysis of the identied remains per mammal size

category (medium/large) to estimate the eects of analytical and recov-

ery biases. e smaller osseous nds in the various sample units and

their division to broad taxonomic and anatomic categories can be used

to estimate what garbage had been disposed of in primary deposition

in each domestic unit. e density of nds may show activity areas

where carcass processing took place within structures, or, alternatively,

which places escaped routine cleaning (corners, under or behind

furniture, etc.).

All bones over 2 cm in length, recovered by hand or by wet sieving,

were scanned under magnication (×3) using an oblique light source

50 nimrod marom and sharon zuckerman

to detect bone surface modications (Blumenchine et al. 1996). ese

include carnivore gnawing, burning, weathering, percussion marks,

cut marks, and root etching. Fracture morphology was recorded for

diagnostic bones that retained diaphyseal fragments (Villa and Mahieu

1991), to provide evidence for fresh bone fracturing (presumably for

marrow extraction) versus fracturing of dry bones due to post-depo-

sitional processes (trampling, sediment weight, weathering). Tapho-

nomic information was listed in the database on a per-locus basis,

enabling interlocus taphonomic comparisons in the frequency of vari-

ous taphonomic indicators.

Data Processing

Comparison of skeleton elements and taxonomic abundances across

strata and architectural units will be performed using standard multi-

variate statistical techniques: correspondence and cluster analyses. Age

determination will rely on both epiphyseal fusion and tooth wear data;

mixture analysis and morphological attributes of horn cores and pubis

bones will be used to determine sex ratios (Greeneld 2006).

Discussion

e basic assumption underlying the excavation of Area S in the Lower

City of Hazor is that cultural processes of rise and decline, centraliza-

tion and decentralization, economic growth and impoverishment of a

city and its inhabitants can all be detected through a careful and prob-

lem-oriented excavation of the households and domestic units. e

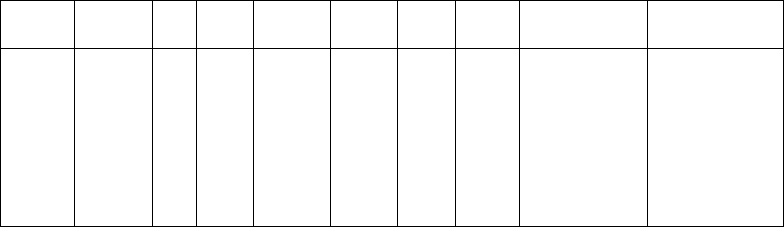

Table 1. An example of the format used to describe the unidentied fraction of wet sieved and

sorted samples

Sample # Date Area Square Locus Basket Height Volume

(litres)

Sample spots Type

6 3/9/2008 S T20 L08-2001 2000/09 225.9 24 diagonal, NE-SW wet-sieving, 1 mm

7 5/9/2008 S A20 L08-2008 2000/47 225.53 18 diagonal, NE-SW wet-sieving, 1 mm

8 5/9/2008 S S20 L08-2006 2000/50 226.03 22 diagonal, NW-SE wet-sieving, 1 mm

9 5/9/2008 S T1 L08-2000 2000/51 225.87 20 diagonal, NW-SE wet-sieving, 1 mm

10 5/9/2008 S U1 L08-2004 2000/52 225.64 7 diagonal, NW-SE wet-sieving, 1 mm

11 5/9/2008 S T20 L08-2010 2000/49 225.78 21 diagonal, NW-SE wet-sieving, 1 mm

12 5/9/2008 S U20 L08-2002 2000/48 225.69 23 diagonal, NW-SE wet-sieving, 1 mm

13 8/9/2008 S A20 L08-2008 2000/70 225.46 34 cross wet-sieving, 1 mm

14 8/9/2008 S U20 L08-2012 2000/71 225.61 32 cross wet-sieving, 1 mm

a case study from the lower city of hazor 51

nature and scale of the activities performed by the household (food

and cra production, distribution, consumption, social reproduction)

are expected to change according to larger processes inuencing its

historical and social wider contexts (Wilk and Rathje 1982; Watten-

maker 1998; Robin 2003). A meticulous study of all aspects of material

culture can illuminate issues of mundane life and daily activities of the

urban commoners of Hazor. A better understanding of these facets of

the city’s life will enable us to tackle questions concerning the larger

processes of development and decline aecting the site.

Here we would like to highlight one relevant example of such a

process—the gradual economic decline, leading to a situation of politi-

cal and social strife, witnessed in Canaan during the Late Bronze Age.

is process is well attested both by written documents and in the

archaeological record of the period (Liebowitz 1987; Bienkowski 1989;

Knapp 1989; Bunimovitz 1995). Material indices of these trajectories

might include architectural development and internal alterations in

contemporary structures, changes in pottery vessel form and technology,

variation and stability in the availability and consumption of dierent

foodstus. All these aspects of the archaeological record are assumed

to be sensitive to situations of economic and social stress. At Hazor,

features of “crisis architecture,” “termination rituals,” and deteriora-

tion in other aspects of the LB assemblage were detected in the con-

text of monumental temples and public structures and are interpreted

as the archaeological correlates of this process (Zuckerman 2007a).

According to this reconstruction, these internal conicts and eco-

nomic stresses led, eventually, to the conagration of the monumental

structures in the Lower City and on the acropolis, in a violent destruc-

tion campaign by the city’s inhabitants aimed at the symbols of elite

power.

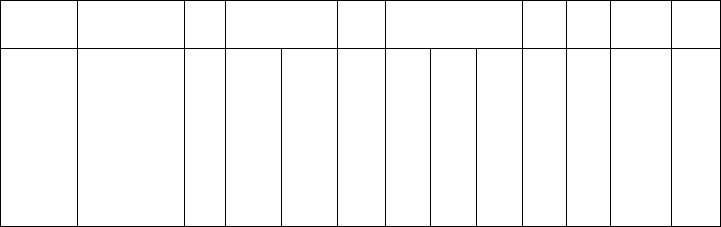

Table 1 (cont.)

Sediment Context NSP Large mammal Medium mammal Bird Fish Rodent Burnt

gray clay under top soil 12 0 0 0 6 0 0 0 0 0 2

gray clay ll 29 0 0 0 7 0 1 0 3 1 5

gray clay ll 35 0 0 0 6 2 0 0 1 0 2

gray clay ll 38 0 0 0 19 1 0 0 0 0 5

gray clay ll 15 0 0 0 8 1 0 0 1 1 4

gray clay ll 47 0 0 0 15 2 0 0 1 0 10

gray clay ll 25 0 0 0 5 0 0 0 1 0 5

gray clay ll 28 0 0 0 14 1 0 0 2 0 4

gray clay ll 41 0 0 0 28 2 0 0 1 1 2