Yasur-Lau Assaf. Household Archaeology in Ancient Israel and Beyond

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

162 yuval gadot

by cyclical shis between periods of strong and integrated social power

and periods during which the area became a frontier zone and a home

for pastoral groups and other marginal elements of society (Gadot

2006, 2008, forthcoming). An example of the latter came at the end of

the thirteenth century bce, following a long period of Egyptian domi-

nance, when the region became a frontier zone. It was during this time

that the Philistines took advantage of the absence of a central govern-

ing power and the ensuing social fragmentation within the region, and

exploited this area for their economic needs. is is reected mainly

by a shi in the settlement pattern in the region and by the appear-

ance of Philistine-related Bichrome pottery at all sites dated to this

time. Based on material culture studies, we know that the Philistines

initially immigrated only to the southern Coastal Plain, to places like

Ashkelon, Ashdod, and Ekron, and only later, aer a few decades, did

they turn their attention to areas surrounding their new homeland,

like the Yarkon region (Singer 1985; Mazar 1985a; Stager 1995; Gadot

2006). It should be noted, in light of the above discussion of ethnic-

ity in “encounter” zones, that the political and economic dominance

of the Philistines over the region does not necessarily mean that the

population was ethnically “Philistine.” In order to determine the pop-

ulation’s ethnic identity, many components constituting the material

culture of the region must be considered, among them houses and the

way they were used.

The Sites

is analysis focuses on four excavated sites dating to the timeframe of

the present inquiry and situated along the Yarkon River:

Tell Qasile: Located two kilometers east of the seashore, Tell Qasile

was rst excavated by B. Mazar (Mazar [Maisler] 1951; Dothan and

Dunayevsky 1993), who excavated Areas A and B located on the

southern and western slopes of the mound. A second expedition to

the site was headed by A. Mazar (Mazar 1980, 1985b, 1986; Mazar

and Harpazi-Ofer 1994), who excavated Area C located on the top of

the tell. Most of the known domestic structures come from Area A,

where an east–west street was unearthed that was anked by houses on

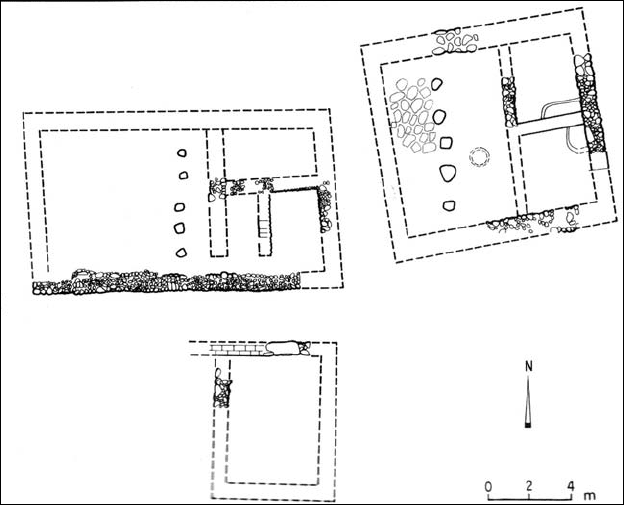

both sides. Stratigraphically, the houses belong to Stratum X (Fig. 2;

Dothan and Dunayesvky 1993: 1205; Mazar 2009: Figs. 1, 3), although

some houses were rst built in Stratum XI. Unfortunately, Area A has

society, economy, and identity 163

Figure 2. Plan of Tel Qasile stratum X (aer Mazar 2009: Figure 1).

164 yuval gadot

Figure 3. Aphek Stratum X11: the northwestern quarter.

only been published in a preliminary fashion that deals mainly with

the architecture; the material culture was never published in a man-

ner that allows for a spatial analysis of human behavior. Additional

domestic structures were found in Area C, where they were dated to

Strata XII, XI, and X (Mazar 2009: 320, Fig. 6). In all, seven complete

houses from Tell Qasile were analyzed in the present study.

Tel Gerisa: is site is located on a projecting kurkar hill, near the

point where the Ayalon and Yarkon Rivers merge a few kilometers to

the east of Tell Qasile. e tell has two summits with a relatively low

saddle between them. Substantial architecture dating to the Iron Age

I was found on the southern summit (Area B) by Z. Herzog, the exca-

vator of the site (Herzog 1993, 1997; Herzog and Tsuk 1995). ese

remains have been published only in a preliminary fashion (Herzog

1993: 483). Hence, the two houses reported from Tel Gerisa are men-

tioned below but are not analyzed in detail.

Tel Aphek: e site of Aphek is located near the rich springs of

Aphek, the main source of water for the Yarkon River (Kochavi

1989a). Remains dating to the Late Bronze Age–Iron Age transition

society, economy, and identity 165

Figure 4. Plan of ‘Izbet Ṣartah stratum III (aer Finkelstein 1986: Fig. 26).

(Stratum X11) and to the Iron Age I (Strata X10–X9) were found only

in Area X, located on the upper tell (Gadot 2006, 2009b). e earlier

stratum includes two domestic quarters (Gadot 2009b: Figs. 6.1, 6.2).

In the later stratum a small farmstead was excavated. e nds include

a domestic structure and a large open space next to it, probably used

as a threshing oor (Gadot 2006, 2009b: Fig. 6.6). Both strata were

abandoned and therefore very few nds were recovered in situ. For

the present study, two houses from Stratum. X11 were scrutinized. e

single domestic unit from Strata X10–X9 is mentioned only briey.

166 yuval gadot

Figure 5. Plan of ‘Izbet Ṣartah stratum II (aer Finkelstein 1986: Fig. 27).

ʿIzbet Ṣartah: e site of ʿIzbet Ṣartah is located along the fringes

of the Coastal Plain and the Samaria Highlands (Finkelstein 1986).

Traditionally, the site has been interpreted as an example of the Isra-

elite settlement in the hill country (Finkelstein 1988; Mazar 1990: 335).

However, the proximity of the site to the Coastal Plain, particularly

to Aphek, suggests that the inhabitants of ʿIzbet Ṣartah shared eco-

nomic and social traits with their western neighbors. I have therefore

included this site as part of this analysis, regardless of the presumed

cultural identity of its inhabitants.

society, economy, and identity 167

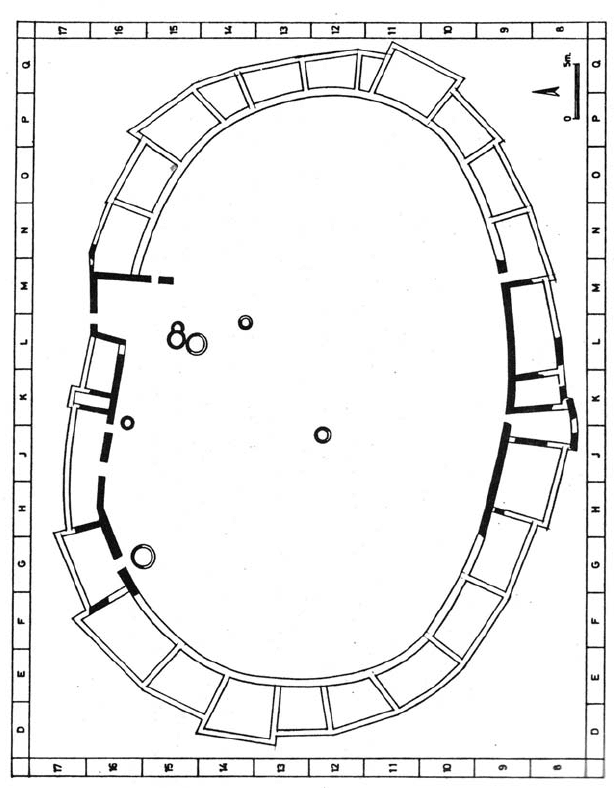

Two main phases of occupation were recognized at ʿIzbet Ṣartah. In

Stratum III a large central open courtyard was surrounded by small

domestic buildings (Fig. 4; Finkelstein 1986: Fig. 26). e second set-

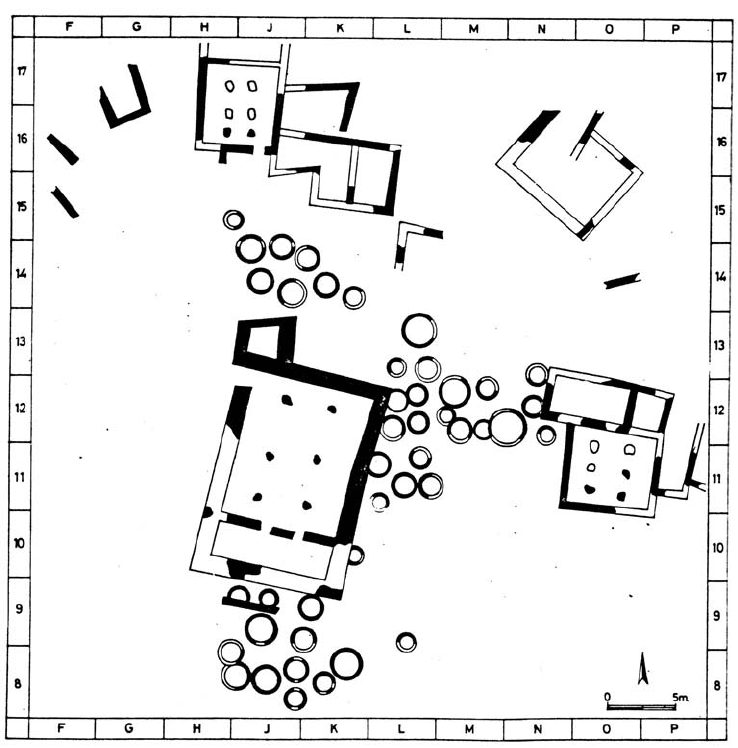

tlement (Strata II and I) was composed of at least three “four-room

houses,” or “pillar houses,” as they were named recently (Mazar 2009:

324), with many silos between them. One of the houses was located at

the center of the site and is considerably larger than the other buildings,

numbering at least two clusters (Fig. 5; Finkelstein 1986: Fig. 27).

Discussion

A holistic archaeological approach demands that both the architecture

and the artifacts located in primary contexts be considered together.

Unfortunately, from the four sites used in this investigation, only at

ʿIzbet Ṣartah Strata II–I is a holistic analysis possible. Aphek and Tel

Gerisa were abandoned in antiquity and no nds were recovered in

primary contexts, and most of the artifacts from Tel Gerisa and some

from Tell Qasile have not yet been published. erefore, the discussion

below will focus mainly on the architectural layout of the buildings

and their location within the settlement. My analysis of human behav-

ior will be drawn mostly by examining installations and the selected

artifacts that have been published to date.

e discussion is divided chronologically. I will rst discuss houses

and households dating to the LBIII/Iron I period (Table 1). is will

be followed by a discussion of living quarters in settlements dating to

the Iron Ib period (Tables 2 and 3).

3

Table 1 presents the available data concerning buildings identied

as houses found in strata dating to the transitional phase between the

Late Bronze Age and the Iron Age. It includes two sites: e rst is

ʿIzbet Ṣartah Stratum III where a circumferential belt of houses encloses

a courtyard (Finkelstein 1986: 106–108, Fig. 4); Excavations at the site

exposed parts of at least ve houses that are all very similar in their

size and nature. House 2007 is the better-preserved example and it

was therefore chosen for analysis below as a representative example.

e second site is Aphek Stratum X11 where two living quarters were

3

e separation into two tables is merley technical, as the houses in Tell Qasile

(Table 3) are compared with other coexisting houses presented in Table 2.

168 yuval gadot

unearthed—the southeastern and northwestern—separated by a public

piazza. e preservation of the southeastern quarter is too fragmentary

to be analyzed and I shall therefore focus on the northwestern quarter

only. Here, two buildings were excavated with similar dimensions. e

plan of House 2942 is more complete between the two existing plans

and was therefore chosen for analysis.

e two sites compared are spatially proximate to each other and

probably coexisted in time, but there are marked dierences in the

settlement plan and the construction of domestic units. Single houses

at Aphek are more complex in plan, with three internal spaces, com-

pared to one in ʿIzbet Ṣartah; they have interior, private courtyards,

while at ʿIzbet Ṣartah there is only one, exterior, shared courtyard;

and they are well built with paved oors and relatively thick walls

4

Based on Finkelstein 1986: Fig. 3.

5

Based on Gadot 2009b: Fig. 6.1.

Table 1. Houses dating to the Late Bronze Age–Iron Age transition

ʿIzbet Ṣartah III

4

Aphek X11: northwestern quarter

5

Building techniques

and materials

One row of eldstone foundations

and mudbricks; the bedrock serves

as the oor

Two rows of eldstone foundations; oors

either paved or of packed earth

Building size Building 2007: exterior

dimensions: 7 m × 5 m; net oor

area: 25–30 m

2

Building 2942: exterior dimensions: 9.5 m ×

7.5 m; net oor area: 48 m

2

; front courtyard

area: 30 m

2

Orientation e opening faces the courtyard

with no special orientation

e openings face north and east

Courtyard location One central shared courtyard:

1450 m

2

Inner courtyard located in the front part

of the house; large exterior public piazza of

unknown dimensions

Complexity,

internal division,

and syntax

Single space and shared courtyard Interior division into three spaces; back

rooms accessible from the courtyard

Location in the

settlement

Located on the perimeter of a hill Built on top of a hill

Relations with

other buildings

Houses share party walls Houses do not share party walls, but are

built next to each other

Uniformity in

architectural layout

e houses are uniform in plan,

but dier in size

e outer plan of the houses is uniform, but

the interior divisions dier from house to

house

society, economy, and identity 169

Table 2. Houses dating to the Iron Age I

ʿIzbet Ṣartah II–I

6

Aphek X10–X9

7

Tel Gerisa

8

Building techniques

and materials

Most houses have wall

foundations built of one row

of unworked eldstones. e

bedrock serves as oor.

Building 109 stands out in its

overall size and the width of its

walls

Wall foundations are made

of one row of unworked

eldstones; packed-earth

oors

Wall foundations are

made of unworked

eldstones

Building size Building 109: exterior

dimensions: ca. 11.5 m × 16 m;

net oor area: 120 m

2

;

Building 301: net oor area:

37.5 m

2

;

Building 916: net oor area:

51 m

2

Too fragmentary for

reconstruction

Too fragmentary for

reconstruction

Orientation Unclear Unclear Unclear

Courtyard location All three have an inner

courtyard; a paved outer

courtyard was found next to

Building 109

Inner courtyard Inner courtyards

located at the front part

of the house

Complexity, internal

division, and syntax

Buildings divided into at least

four rooms, accessed via a

courtyard

Divided into at least three

spaces; entrances cannot

be reconstructed

Division into subspaces;

entrance cannot be

reconstructed

Location in the

settlement

One building is at the center of

the site; the other two are built

on the mound’s perimeter

Built on a hill, next to open

grounds

Built on the top of the

southern hill

Relations with other

buildings

Most buildings are freestanding Only one freestanding

building found

Buildings are

freestanding

Uniformity in

architectural layout

Buildings share similar plan,

but are not identical

Cannot be determined Buildings are built

according to dierent

blueprints

that are not shared with neighboring buildings, as opposed to ʿIzbet

Ṣartah’s domestic units. At the same time, the living space inside the

buildings is relatively similar at the two settlements (25–30 m

2

at ʿIzbet

Ṣartah and 30 m

2

at Aphek). More dierences can be noticed in the

settlement’s layout. While both sites have a public piazza/courtyard,

6

Based on Finkelstein 1986: Fig. 4.

7

Based on Gadot 2009b: Fig. 6.6.

8

Based on Herzog 1993.

170 yuval gadot

the buildings surrounding the unpaved courtyard at ʿIzbet Ṣartah are

arranged in a standardized, almost rigid, plan; the Aphek piazza is

stone paved, but the arrangement of the houses built close to it exhib-

its no apparent preplanning.

It seems that the dierences in the layout of the two settlements and

in the ground plan of the buildings derive from the signicance given

to the individual family in society and, consequently, to the individual

building. At ʿIzbet Ṣartah Stratum III the single house has very little

signicance in itself, and is only a component of the overall plan. Fin-

kelstein has noted that the ratio between the public and private spaces

at ʿIzbet Ṣartah is 65: 35 (Finkelstein 1986: 106). is means that a

Table 3. Houses at Tell Qasile

9

Pillar houses: (Area A) Pillar houses:

(Area C)

Courtyard House O

Building techniques

and materials

Fieldstones and mudbricks Fieldstones and

mudbricks; thick walls

Fieldstones and

mudbricks

Building size K: 9.1 m × 9.1 m; 51 m

2

;

J: 8.8 m × 10.1 m; 60 m

2

;

W: 9.1 m × 10.1 m; 77 m

2

;

R: 10.4 m × 9.9 m; 64 m

2

225: 8.5 m × 13.5 m; 77 m

2

;

495: 10.7 m × 13.4 m;

92 m

2

12.5 m × 12.9 m;

139 m

2

Orientation Entrance facing street Entrance facing street Entrance facing street

Courtyard location Inner courtyard located in the

front part of the house

Inner courtyard located in

the front part of house

Inner courtyard located

in the central part of

house

Complexity, internal

division, and syntax

Four spaces, all accessed via

the courtyard

Four spaces, some not

accessible from the

courtyard

At least ve spaces

arranged around a

courtyard

Location in the

settlement

Built along a street on the

southwestern slope of the hill

Built on top of the hill,

close to the temple

Inside the settlement,

between the temple and

the pillar houses

Relations with other

buildings

Buildings share party walls Building 495 is separate

from other buildings;

Building 225 shares a party

wall with the temple

Shares no walls with

building W; shares one

wall with building J

Uniformity in

architectural layout

Buildings share a similar plan,

but vary in sizes

Plans are similar in idea,

but each building has some

unique additions

Only one building

9

e information here is based on Mazar 2009: Tables 2, 3.

society, economy, and identity 171

majority of the everyday activities were preformed out in the pub-

lic realm, while considerably less space was allotted to the individual

family. e preplanned settlement and the uniformity of its houses in

size, plan, and construction quality show that the occupants of ʿIzbet

Ṣartah formed a closely integrated social group, which suppressed the

place of the individual family. Scholars studying the emergence of

village society during the time of the Neolithic Revolution stress the

move to autonomous households as one that bettered productivity,

and lead to the creation of social stratication (e.g. Byrd 1994, 2000).

e buildings at Aphek are organized as autonomous households. e

architectural layout at ʿIzbet Ṣartah reects an entirely dierent pref-

erence that emphasizes the public arena. According to the excavator

(Finkelstein 1986: 106–109), the need for a large public courtyard was

explained as reecting economic or functional considerations. Accord-

ing to Finkelstein, the plan of the settlement proves that the site was

occupied by pastoralists who had shied to a sedentary lifestyle. e

tent camp was replaced by stone-built houses that retained the former

dwellings’ tent-like shape (Finkelstein 1986: 116–121). e courtyard

was used for penning the herds—sheep and goats or camels—at night.

Finkelstein (1986: 118) notes that some pastoralists’ camps were built

along a linear axis, while others, like at ʿIzbet Ṣartah, enclosed a court-

yard. e particular arrangement was explained by security needs,

by the nature of the animals herded, or according to topographical

considerations.

Apart from the courtyard’s role in the survival strategy of the site’s

inhabitants, its public nature and the fact that most of the everyday

activities were preformed there communally by members of the group

point to the fact that the courtyard also played a signicant role in

regulating and maintaining social order and in the control of the

individual by the larger group. e importance of public space for

integrating and strengthening social bonds in villages that are based

on autonomous households was mentioned by Byrd (Byrd 1994; see

also Rosenberg and Redding 2000: 47–49). e layout of ʿIzbet Ṣartah,

however, is a combination of a large public courtyard and a consi-

derably small overall area of autonomous spaces. is meant that

everyday activities, such as food preparation and consumption, were

preformed in an open area. ere was no escape from public scrutiny. e

power of social surveillance of the ruling elite or of lower-ranking

members of society is known as a key for regulating social order and