Yasur-Lau Assaf. Household Archaeology in Ancient Israel and Beyond

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

122 itzhaq shai et al.

Table 1

Denition Size

(meters)

Walls:

width and

material

Relation to

other

buildings

Courtyard Floors References

Tell eṣ-Ṣa/

Gath

— 20 × 12 0.8–1 m,

eldstones

and

mudbricks

Not

attached

from the

north,

south, or

east

Inner

courtyard

? Shai et al.

forthcoming

Aphek Governors’

residence

20 × 20 1.4 m,

eldstones

and

mudbricks

Isolated

building

Outside

building

2 Gadot 2009a:

55

Tell el-

Farʿah (S)

Governors’

residence

23 × 22 1.5–2 m,

mudbricks

Two

isolated

buildings

Outside

building

hall

2 Oren 1992:

119–120,

Fig. 22

Tel Mor Governors’

residence /

fort, St. VIII

22.5 × 22.5 2–2.5 m,

mudbricks

Not

attached to

other

buildings

Small inner

court and

outer court

to the west

2 Barako 2007:

20, Plan 4.2

Tel Seraʿ Governors’

residence

25 × 25 2 m,

mudbricks

? Inner court ? Oren 1992:

118, Fig. 17

Gezer ‘Main

building’

19 × 13 ? Stone Attached to

ancient city

wall

Inner

courtyard

2 Herzog 1997:

178–179,

Fig. 4.30: C

Ashdod Governors’

residence

(Area G)

? 2 m,

eldstones

and

mudbricks

Not

attached

Inner

courts

? Dothan and

Porath 1993:

41–43, Plan 7

Tell Beit

Mirsim

Patrician

house

Ca. 20 × 20 1.3 m,

mudbricks

?Front

courtyard

? Oren 1992:

116, Fig. 14

Tel Batash Patrician

house

(St. VIII,

Building 475)

14 × 13 1.2 m, stone Not

attached to

other

buildings

Inner

courtyard

2 Mazar 1997b:

52, Fig 1.5

Tel Harassim House,

Building 305

14 × 13 Ca. 0.8 m,

eldstones

Not

a

ttached to

other

buildings

Outer court

in front of

building

1 Givon 1999:

Fig. 2

Taʿanakh Fort/patrician

house

18 × 20 1.2 m, stone ? Front

courtyard

2 Oren 1992:

116, Fig. 15

Megiddo Courtyard

house,

Stratum VI A

15 × 15 Stone and

mudbricks

Not

attached

Inner

courtyard

1 Gadot and

Yasur Landau

2006

Ashdod Courtyard

house

(Area B)

12 × 17 1.1/0.6 m,

mudbricks

Part of

domestic

quarter

Inner

courtyard

? Oren 1992:

116, Fig. 13;

Daviau 1993:

312–317

Ashdod 5381 Courtyard

house

Ca. 14 × 16 0.8 m,

mudbricks

Attached Inner

courtyard

1 Mazar and

Ben-Shlomo

2005: 16, Plan

2.2

a case study from late bronze age ii 123

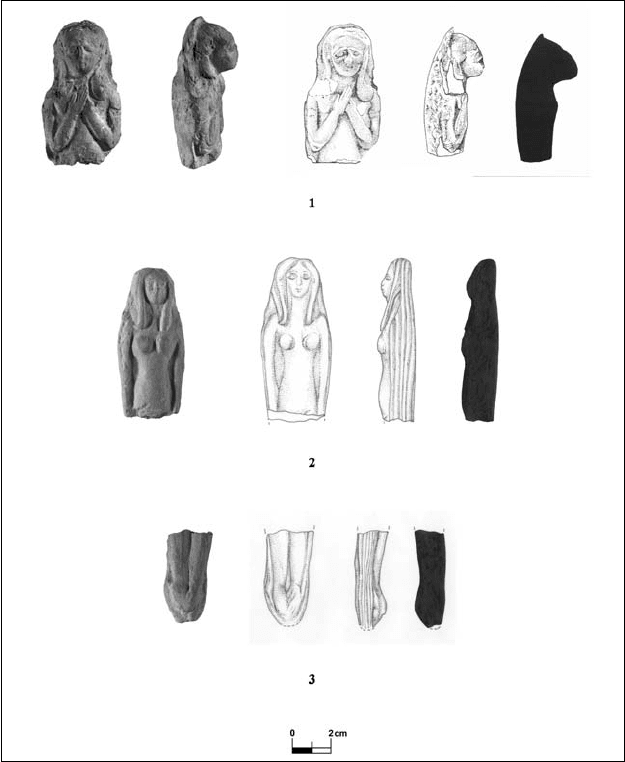

Figure 11. LB plaque gurines from Area E.

124 itzhaq shai et al.

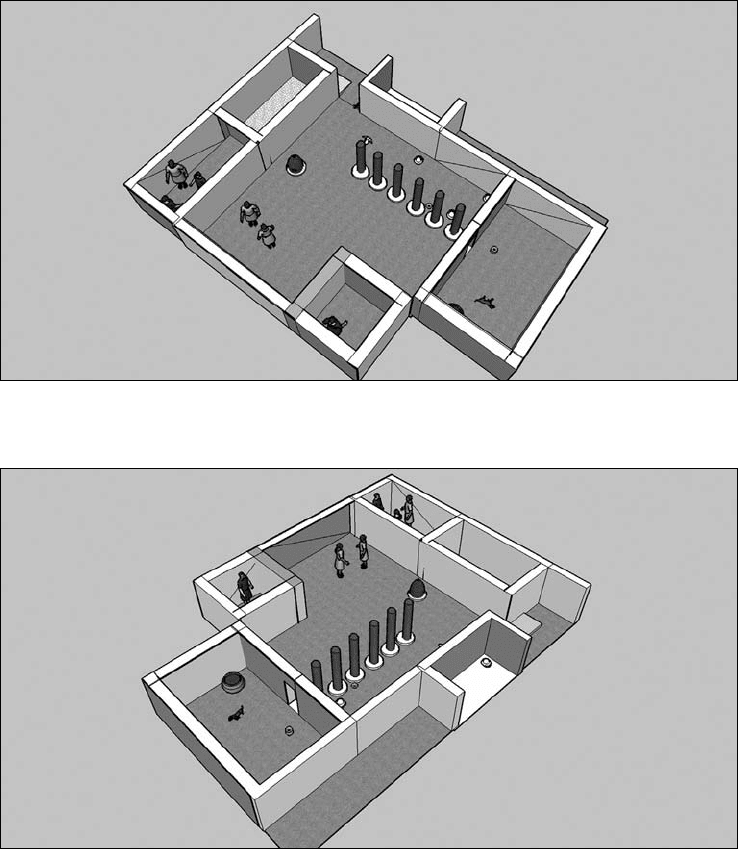

no sign of an entrance, and the eastern side faces a relatively steep slope.

It is assumed that from this western entrance, a narrow corridor led into

the central feature of Building 66323-a courtyard (66009). As mentioned

above, this reconstruction is based on a comparison to Building 475 at

Tel Batash (Mazar 1997b: 52, Fig. 1.5). It should be noted that, when

entering the building, one did not go straight into the courtyard but

rather through a passageway. e entrance to the central courtyard

was therefore controlled: rst, one would have to go through the pas-

sageway, and then one would have to enter the courtyard through a

relatively narrow entrance (ca. 1 m wide). e courtyard is divided by

a row of pillar bases, which is seen in other “public” buildings in LB

Canaan, such as at Tel Batash, Strata VIII–VII (Building 475: Mazar

1997b: 52–57; Panitz-Cohen 2006a: 176–183, Fig. 15; Building 315:

Mazar 1997b: 58–72; Panitz-Cohen 2006a: 183–190, Fig. 16). Since the

access to the other rooms was from the main courtyard, movement in

the house was also controlled.

e restricted entrance into an inner court characterizes almost all

of the houses in Table 1. However, there are slight dierences that

may indicate social values and restrictions. e governors’ residences

feature an outer court located in front of the entrance and only a small

inner court. is seems to indicate that the outer (ceremonial?) court

was part of the public domain, while the entrance into the rst oor

of the building, the location of the storerooms, was more restricted.

In the smaller domestic structures, such as Buildings 305 and 315 at

Tel Batash (Mazar 1997b: Figs. 13–14), the external entrance leads

directly into the main, inner court; for comparison, a similar syntax is

seen in the four-room houses of the Iron Age (Bunimovitz and Faust

2003a; 2003b). e “courtyard houses” at Ashdod and Megiddo and

the “Patrician House” at Tel Batash all have a small entrance room

that separates the external world from the inner court, i.e., the center

of the house. is may indicate conceptual dichotomies of external vs.

internal and public vs. private or domestic. Due to the limits of the

excavated area and architectural preservation in this case, we do not

know if an outer court similar to those in the governors’ residences

existed in front of building 66323. As it seems that the building did

not have such a court (based on comparative data—see Table 1), the

syntax of Building 66323 is most similar to the urban courtyard and

patrician buildings.

e location of the building: e location of Building 66323 is also

of interest, as it is not situated on the upper part of the mound, but

a case study from late bronze age ii 125

rather on its easternmost slopes, in what would appear to be a rather

peripheral part of the site. It seems that this location may have been

an intentional act, separating the building from other structures in the

city, as well as making it stand out on the landscape of the site.

5

Most

importantly, the building’s location may help us understand aspects of

the sociopolitical structure in Gath during the thirteenth century bce.

While this period is usually thought to be a period of economic regres-

sion (e.g., Dever 1992), it seems that Gath ourished during this time,

expanding to include the eastern slopes of the site, an area that was

only settled in periods when the site reached a peak in size (and see

Uziel and Maeir 2005 for a comparison between LB Gath and Ekron).

One should note that excavations in other parts of the site (most nota-

bly Areas P and F) have revealed impressive LB architectural remains,

indicating that the architectural and urban fabric of Tell eṣ-Ṣa/Gath

during the thirteenth century bce was not one of regression and crisis,

but of a ourit.

6

Building 66323: Suggested Use of Space

A spatial analysis of the nds from the building at Tell eṣ-Ṣa/Gath

is a dicult task that requires much care and awareness of formation

processes (e.g., Schier 1983, 1985) (Figs. 10, 12, 13). As the building

is located on the slope of the tell, many of the original artifacts may

have washed down slope; therefore, their excavated location reects

secondary deposition. Furthermore, the proximity of the building to

the surface may have adversely aected the deposition of artifacts as

well as their post-depositional history (although in certain areas, the

Stratum E4b contexts were sealed from above, particularly in the west-

ern parts of the building). However, the most signicant aspect in the

deposition of the artifacts, which makes spatial analysis a dicult task

to undertake, is the fact that most of the pottery, which represents the

5

Interestingly, one can note Aurenche, Bazin, and Sadler’s (1997: 136) observation

that one of the criteria for dening the houses of the wealthiest families in contem-

porary villages in the Keban region, Turkey, is their location on the periphery of the

village.

6

ere are other sites where there is evidence for prosperity at the end of the Late

Bronze Age—see, e.g., Megiddo (Ussishkin 1998).

126 itzhaq shai et al.

majority of nds relevant for this study, is sherds.

7

is may be due

to the long period of time in which the building was in use, the way

in which the building went out of use, or various post-depositional

activities. In addition, certain areas appear to exhibit signs of destruc-

tion while others seem to have been simply abandoned.

Despite these diculties, the location of some of the nds does hint

to the activities conducted in dierent rooms and in the building in

general. e presence of at least one tabun (49022) on the south side of

the courtyard suggests that cooking was conducted within the build-

ing. e vessels found in proximity to the tabun (including storage

jars and cooking pots) also indicate that the area was used for food

preparation. Additional evidence for cooking and food preparation is

seen in other parts of the building as well, as several cooking pots (e.g.,

Fig. 5: 12–14) and grinding implements were found throughout. It is

interesting to note the large size of one of these cooking pots (Fig. 5:

14); with a diameter of 50 cm, it appears that such vessels were used

to cook for a large group of people in Building 66323.

Other nds that indicate specic activities in dierent rooms include

the archaeobotanical remains, including wheat, in Room 84010, indi-

cating that the room served either for storage or food preparation

(Mahler-Slasky and Kislev forthcoming). Interestingly, the location of

this room at the entrance to the building is similar to the location

of the grains found in the entrance room at Tel Batash (Room 347;

Mazar 1997b: 66). While pending nal analysis, int tools (includ-

ing sickle blades) were recovered in various locations in the building,

indicating another aspect of daily life.

e presence of nds that could be interpreted as luxury items, such

as imported Cypriot and Mycenaean pottery, is commonplace in the

LB southern Levant (Gadot et al. forthcoming). However, as opposed

to most Mycenaean imports from other LB sites, which include pri-

marily small, closed containers, the Mycenaean imports from this

building included a signicant sample of large serving vessels (i.e.,

kraters and jugs) and few small containers (Gadot et al. forthcoming).

7

e many and varied forms of foundation deposits mentioned above are inter-

preted as being connected to the establishment of the building, and therefore cannot

be used for making inferences about behavior inside the building or the function

of rooms throughout the extended use history of the building. Nevertheless, these

numerous deposits do hint to the original status and ideological importance of this

building, perhaps indicating its somewhat sacred status.

a case study from late bronze age ii 127

Figure 12. Isometric reconstruction of Building 66323, looking southwest.

Figure 13. Isometric reconstruction of Building 66323, looking southeast.

128 itzhaq shai et al.

While this may be a result of the small sample of imports found in

Building 66323, it stands in contrast to data from other sites in the

region (e.g., French and Sherratt 2004; Yasur-Landau 2005). Together

with the large-sized cooking pot noted above, one can perhaps suggest

that some kind of feasting occurred in the building.

8

e installation built of yellow mudbricks and lined with eldstones

in Room 84011 is of importance. e exact activity conducted in this

installation is dicult to determine; however, the presence of relatively

high quantities of metal in the sediments nearby (discerned through

chemical analyses; S. Weiner, personal communication), as well as a

dagger deposit in the foundation trench of Wall 56018 (see below),

may bear witness to metallurgical activities in Building 66323. Met-

allurgical activities are generally not considered within the realm of

household production (e.g., Daviau 1993: 437–438), which is further

indication of the nonprivate character of this building.

e pottery assemblage of Building 66323 is typical of the Late

Bronze Age (Figs. 6–9) and includes bowls, cooking pots, and stor-

age jars; for the most part, it can be compared to pottery from many

dierent contemporary contexts (for full discussion, see Gadot et al.

forthcoming). e plaque gurines (Fig. 11) are also commonplace in

LB Canaan (e.g., Tadmor 1981). However, one can identify a number

of more unique features within this assemblage. First, four cup-and-

saucer vessels were found in the building (e.g., Fig. 6: 10). While these

are not unique to Tell eṣ-Ṣa/Gath, they are oen associated with cul-

tic activity (e.g., Uziel and Gadot 2010), with numerous examples hav-

ing been found in cultic contexts, such as the Fosse Temple at nearby

Lachish (Tufnell et al. 1940: Pl. 44). Several groups of astragali (Lev-

Tov forthcoming) were also found in the building, likely indicating

another aspect of cultic activity that took place there (see Gilmour

1997).

To this, one can add that quite a few Egyptian and Egyptianizing

scarabs and seals were discovered in the building (Münger and Keel

forthcoming). ese nds might hint to a possible administrative (or at

least administratively oriented) function for this building; however, they

might just be indicative of the auence of the people who lived in it.

Finally, in the occupational debris of Room 58037, an incised hier-

atic sherd was found. It was locally made, inscribed before ring, and

8

On Canaanite feasting, see, e.g., Yasur-Landau 2005; Zuckerman 2007b.

a case study from late bronze age ii 129

it was paleographically dated to the Ramesside period, with an an-

ity toward the late Nineteenth or early Twentieth Egyptian Dynas-

ties (late thirteenth/early twelh centuries bce; Maeir et al. 2004).

e suggested reading as S

̌

ps, meaning “noble, precious, august,” can

be explained as a label marking the content of a vessel (Maeir et al.

2004). In Egypt, vessels with these markings were usually made of

stone and used in cultic or mortuary contexts (Wimmer forthcoming).

is sherd reects a mixture of two writing traditions (Egyptian—a

hieratic inscription—and Canaanite—inscribing a vessel before ring;

Maeir et al. 2004: 133). Of interest to this study is the fact that we

have evidence of writing, which is perhaps related to cultic activity,

or, as noted above, to some sort of administrative activity (on the use

of writing in LB Canaan, see, e.g., van der Toorn 2000; Wimmer and

Maeir 2007).

From the above, it appears that the building, while serving some

“domestic functions,” had many aspects that hint to functions and

meanings beyond the quotidian. e relatively large size of the build-

ing, the unique architectural features (pillars), as well as the many

nonmundane nds (imported objects, Egyptiaca, and cult-oriented

objects), seem to indicate that the building either served as the abode

of a person/family of elevated social status, or for some public function.

Conclusions

e building that we have discussed is clearly unique both in its size

and in several of its nds. It is dicult, however, to determine the

function(s) of the building. On one hand, the identication of cook-

ing activities and food preparation suggests domestic activities, but the

cooking and serving activities may have been for groups larger than

a nuclear family. Other nds suggest that the function of the build-

ing and the activities conducted within it were not typical household

activities. is relates to the question addressed in the title, that of

distinguishing between public and private architecture. Size is many

times used to dene public buildings (betting Building 66323), yet an

elite dwelling, or a dwelling of an extended family, might also be very

large (Chesson 2003: 87).

It seems that, in this case, a number of aspects do suggest that the

building served as a dwelling; however, it was not a standard domestic

structure. To start with, the row of pillars in the center of the building

130 itzhaq shai et al.

suggests an architectural style not typical of dwellings, not even large

ones. Furthermore, the possible production of metal within the building

or in its vicinity is uncommon in domestic contexts in the Late Bronze

Age. e presence of scarabs, seals, an Egyptian inscription, various

ceramic imports, and nds that indicate feasting may all t with an

interpretation of the structure as an elite dwelling. Most telling, per-

haps, is the cultic/ideological endorsement given to the building when

it was constructed, as evidenced by the placement of numerous foun-

dation deposits, both the unusually large number of lamp-and-bowl

deposits, and also the more unique deposits (the bovine skull, don-

key jaw, dog skeleton, and MB dagger). It is therefore suggested that

the building probably had a public nature, with cultic activities taking

place within its connes (suggested by certain vessels and deposits), as

well as feasting and, perhaps, the production of metals. Perhaps these

activities were linked to a person of elevated social status. Conceivably,

the domestic areas were on an upper oor of the building, but as of

now, there is insucient evidence to determine if in fact there was an

upper oor, and, if so, what activities were conducted there.

Our understanding of the restriction of movement within the

house—controlled through the central courtyard—further reects the

use of certain spaces as more private and restricted areas (in general,

see Hillier and Hanson 1984: 176–197). Similar concepts of restricting

movement within the house have been identied in other architectural

plans in other periods in the Levant. For example, Bunimovitz and

Faust (2003a; 2003b) suggest that the design of the four-room house

was intended to allow for the separation of the pure and impure, with

dierential access to the dierent rooms within the house. A similar

situation does not exist in Building 66323. While access to the building

was not restricted as, for example, in the Minoan villa (Preziosi and

Hitchcock 1999: 111), it clearly was not meant to have unrestricted

access from the external world; an eort seems to have been made to

restrict access to the internal parts of this building, where, perhaps,

private activities were conducted. Perhaps not everyone was welcome

to participate in and see these activities from the outside (for a dis-

cussion of preferential viewing of the interior of elite houses by the

“outside world,” see, e.g., Hendon 2004: 276). Without reconstructing

all of the activities occurring in the dierent rooms (and see above, for

the problems with doing so in Building 66323), it is dicult to explain

clearly why access to Rooms 58036, 68016, and 66325 was controlled.

However, it seems that controlled access was part of the way in which

a case study from late bronze age ii 131

patrician houses in general were planned and built. We suggest that

the architectural model behind these patrician houses included spaces

that were public (in the sense that anyone allowed into the building

was given access), alongside private rooms, with more limited, private

space. e design of the building at Tell eṣ-Ṣa/Gath may also have

allowed for limited interaction between inhabitants, as the rooms were

set on dierent sides of the courtyard. us, while those using Room

58036 would have had access to Room 68016, they would not neces-

sarily be allowed to access Room 66325 or other rooms in the house

(see Grahame 1997, for further interpretations on strangers, inhabit-

ants, and access in domestic space).

9

In conclusion, the study of Building 66323 demonstrates the di-

culties in dening a building as public or private, and dening if a

building falls in between these two extremes. We believe though that it

is possible to understand the function and meaning of such a building

more fully only through a close analysis of both the architectural and

artifactual evidence, along with what can be reconstructed about the

activities that took place in the building.

9

It should be noted that, based on the available evidence from the building, there

does not seem to be any clear indication for the dierentiation of gender-related

activities.