Wakeman Rosemary. The Heroic City: Paris, 1945-1958

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

336 | chapter seven

from its commercial animation. What makes its life so curious, so amusing,

is the activity, the mélange of classes, the best artisanal features.” In a slap to

Vichy’s version of a past filled with Renaissance treasures, and pointing to the

Saint-Gervais neighborhood in particular, Debidour argued that “it would be

imprudent to implement an exaggerated passéiste zoning that assaulted life in

the name of history.” A taste for the past, he warned, “can risk unjustifiable

sacrifices and fall into the artificial.”

87

In Destinée de Paris, Pillement wrote

that “what is regrettable in the Marais is not the destruction of such-and-such

edifice, however irreplaceable, but the disappearance of the atmosphere that

makes Paris charming and still survives in certain neighborhoods that evoke

the most glorious, the darkest, the most tragic and the happiest episodes in

our history” (emphasis added).

88

One cannot help but call to mind Arletty’s

plaintive cry of “Atmosphere! atmosphere!” on the bridge over the canal

Saint-Martin in Marcel Carné’s Hôtel du Nord. The preservationist camp had

leapt from the defense of historic monuments to the evocation of an invented

urban ambience, emotional in content. It was, Pillement argued, these îlots

pittoresques that the state and the city should protect rather than demolish.

In 1943 the process of hounding the population out of the neighborhood

and tearing down buildings was stopped. Without alternative housing for the

displaced, and facing bombardment and the stringencies of war, Vichy’s ur-

ban renewal ground to a halt. By the Liberation, the city was left with an area

teetering on the edge of physical collapse. The heat of the immediate postwar

purges and retribution caused Vichy’s Renaissance dreams for the Marais to

be thrown aside, at least rhetorically. In an ironic reversal of Vichy policy, the

buildings expropriated during the occupation were used in 1945 to house

prisoners and deportees returning from Germany and the camps. The con-

tinued lack of resources left the Marais in limbo for years after the war, as it

did all of the îlots insalubres in the city center. Prefect Roger Verlomme argued,

in the first postwar assessment of the situation, that a middle ground had to

be found somewhere between the aggressive modernist plans for complete

clearance and the preservation opposition to any demolition whatsoever. He

called for a “complex and delicate balance between aesthetics and hygiene” in

considering the area’s future. Innovative modern planning techniques would

go hand in hand with safeguarding the area’s picturesque qualities.

89

As a model of what could be done, Michel Roux-Spitz offered an archi-

tectural motif consistent with the distinctive visual imagery associated with

the capital, the so-called City of Paris design. It was presented in the pages

planning paris | 337

of L’Architecture française and attempted to introduce a vernacular modern-

ism usable for construction in the historic districts. Along with Auzelle and

Sébille, Roux-Spitz had been instrumental in formulating the îlot as the basis

of urban composition. The City of Paris style was meant to be built within this

spatial context. Based on a sober classicism, traditional materials, and simple

facades, the buildings would harmonize with the vieux quartier.

90

Offered at

a reasonable price, the orthogonal stands of discrete three- and four-story

row houses of different sizes abutted the street. The interior courtyards and

alleyways that had made for such a warren of dereliction were prohibited,

to be replaced by gardens and green space. Lastly, strict regulation would

protect the newly invented historic district and educate the popular classes

about aesthetic values. The designs avoided “tasteless” decoration, prohib-

ited the balconies that had served as stashes for laundry lines and coal bins,

and offered sensible interiors with modern kitchens and bathrooms where

families could gather and live decently.

But even though the plans were based on the humanist imaginary of îlot

and renovation and called for repairing the best of the housing stock in the

Marais, it was still assumed that less than half the population would continue

to live there. The rest would be removed to the modern housing projects

planned for the suburbs. In Les Parisiens (1967), even the historian Louis

Chevalier refused to see the Marais as a legitimate working-class social unit

or quartier: “The Marais represented an entity in the originality of its built

environment, but not in human terms.” It was incontestably an authentic

pays parisien until the end of the nineteenth century but had since fallen into

disgrace. Despite its monuments and historic landscape, despite the “hal-

lucinating” survival of the area’s ancient pathways, history had not looked

kindly on the Marais, and few Parisians other than the preservationists con-

cerned themselves with it.

91

And for them, the poor were expendable in the

effort to “save” the neighborhood. As an example, socialist Henri Vergnolle,

president of the municipal council in 1946–47, suggested moving all of the

city’s most important historic monuments and buildings into one of the old

districts, for example the Saint-Gervais district in the Marais, where they

would constitute a quartier des vieilles pierres (neighborhood of ruins), a sort

of carnavalet de plein air (outdoor museum). This monumental handing over

of one of the îlot insalubre to the preservationists would allow the rest of the

central city to be redeveloped.

92

Although the Marais was among the city’s

most venerable working-class districts, it could be sacrificed. It was an irony

338 | chapter seven

born of humanist compromise. The communists on the municipal council

remained adamantly opposed to the plans for the neighborhood as yet an-

other attempt to conquer working-class terrain and banish its inhabitants

to the outskirts. The indemnities offered to the dispossessed became a hotly

contested political issue. The PCF accused the police of terrorizing families

in îlot 16 by periodically rounding them up at the police commissariat and

pressuring them to leave the miserable lodgings they inhabited. But the die

had been cast.

The municipal council eventually approved the idea of a “Cité interna-

tionale des arts” for îlot 16 that would attract foreign investment and act as a

sort of modern Medici villa for Paris. In 1952, as part of the ongoing negotia-

tions with the municipal council, André Prothin, the state’s Directeur général

de l’aménagement du territoire, offered a zoning plan that would extend the

“university zone” in the 5th arrondissement across the Seine into the Marais.

It was not a question of purging all of the artisan and commercial activity,

Prothin argued, “but of freeing up the old hôtels of those activities that can

be advantageously replaced by libraries, cultural, and study centers. They

would guarantee the conservation of the buildings and provide a dignified

framework for the growth of the University of Paris.” Once the slums were

cleared out, new housing would be offered to professors and students. To

safeguard the neighborhood’s picturesque streets and public spaces, only

artisans offering high-class goods, antique dealers, interior decorators, high-

fashion boutiques, and bookstores would be welcomed. The Marais would

be cleared of automobile traffic and reoriented toward the banks of the Seine

and the Latin Quarter. The once distinguished district would emerge from

its isolation and come to life as a vital part of the larger urban fabric. This

kind of planning “would allow Paris to conserve and put to good use one of

its oldest and most evocative neighborhoods, one that lovers of France have

not been able to fully appreciate because of what currently exists there.”

93

The reference to tourism was unequivocal.

The task of designing the restoration for îlot 16 remained largely in the

hands of Albert Laprade through the 1950s and early 1960s. Trained at the

École des beaux-arts, Laprade remained loyal to French architectural and

urbanistic proclivities rather than to the modernism offered by CIAM. He

had been involved in the debates over the Marais since well before the war.

He and the architect Jean-Charles Moreux had originally offered their own

counterdesigns for the district in the pages of L’Illustration in 1938 and 1941,

planning paris | 339

including an early call for façadisme, the inspired suggestion that buildings

might be destroyed if their facades were saved. A practitioner of humanist

urbanism, Laprade argued that “reconquering” Paris was achievable without

wiping out the historical fabric. The most difficult and urgent task in Paris was

to “liberate the îlot” by clearing out the detritus and showcasing the original

urban typography. Like Auzelle, he argued for renovation, for planting trees,

for new construction that harmonized with existing infrastructure. In a 1957

article entitled “Aménagement des quartiers historiques,”

94

Laprade offered

two examples of this design approach for îlot 16, both of which evidenced

the mounting ironies of poetic humanist discourse by the end of the decade.

Although the choices offered effectively saved the Marais from wholesale

demolition, they were far less about the beauty, mystery, and insight found

among le peuple and far more about reifying the built environment. It was a

form of historicist remembering that favored social elitism and a touristic

gaze. The first example was the site of the old cemetery of Saint-Gervais,

where many of the master artisans of the Middle Ages and Renaissance

lay. The area was cleared of the working-class squatter structures that had

been accumulating over the tombs since the early nineteenth century. Under

Laprade’s guidance the space was transformed into an urban garden, with the

renovated buildings around it enjoying the view and “complete calm.” In the

second example, the dilapidated buildings surrounding Saint-Gervais Church

were demolished to make way for a corner garden and children’s crèche. The

aesthetic purpose, however, was to open up the view of the church’s flying

buttresses and peaked roofline.

From these battles over îlot insalubre 16 came a new idealization of the his-

toric district. This vision was not intrinsic to the Marais, but was the product

of a broad-based, multifaceted public dialog and conscious visual invention.

The 1961 Festival of the Marais that opened the district’s renowned aristo-

cratic townhouses for public viewing attracted large crowds and mobilized

Parisians into believing the district was worth saving. The CDU carried out a

massive statistical, architectural, and topographic study of the Marais in 1961

and 1962, on the basis of which its future would be designed.

95

The architec-

tural inventory resulted in a listing of 56 buildings of “very great quality,” 121

buildings listed as historic monuments, and 526 buildings deemed of “very

great interest” worthy of protection. In addition, more than 1,000 structures

belonged to a category of “buildings of accompaniment or atmosphere” that

were vital to the district’s perceived environment, scale, and harmony. Build-

340 | chapter seven

ings and gardens were renovated, facades cleaned, courtyards and sinuous

streets cleared. Various cultural institutions set up headquarters in the 102

landmarked palaces and townhouses in the Marais, helped by their purchase

and restoration by the city of Paris.

In 1962 a new national preservation law, christened the Malraux Law,

permitted the registering of entire districts as protected landmarks, or secteurs

sauvegardés. They were defined as areas or complexes of buildings whose pres-

ervation was desirable for either historic or aesthetic reasons. The Marais was

classified as a secteur sauvegardé in 1964, the first such area in Paris and the

largest in France. The Malraux Law defined the Marais in terms not only of

its architectural beauty, but also of its ambience and tone, its shabby quaint-

ness. It reemerged as a space of historicism and ultimately of middle-class

tourism. The “right to the city” was grossly curtailed and became more and

more an elitist prerogative. The district was produced as an architectural and

atmospheric museum, a visual fantasyland. The more Paris changed under

the impact of modern urban planning, the more the Marais and neighbor-

hoods like it were depicted and defended as staying the same. The value and

readability of public space was associated with wandering through a visual

landscape caught in a moment of time. This imaginary was static and rigidly

conformist. The process of reification constructed an acceptable past and cut

entities off from their own history. The peuple and their magical place making

were banished from these sacred precincts. The October 1956 inauguration

of the Memorial to the Unknown Jewish Martyr on the rue Geoffroy l’Asnier

in which ashes from the death camps and the Warsaw ghetto were entombed,

was one of the few, if ironic, attempts to reclaim the neighborhood’s compli-

cated and darker memories. On the whole, however, the district gained an

invented self-consciousness that in fact hollowed out the space of its public

life and veiled the complexities of meaning written in its landscape. The

Marais’s preservation and abstraction could then be reiterated for all of the

historic central districts bordering the Seine to create a dramatic historicist

stage set deeply associated with Paris as a touristic imaginary.

341

constructing the Paris of Tomorrow

In 1964 the architect Noël Boutet de Monvel published his

Les Demains de Paris, a study of the capital’s state of affairs financed by the

Délégation général au district de la région de Paris. It began with the ques-

tion of whether Paris was at a crossroads. Paris, he said, was “a living organ-

ism that energized the entire country.” But underneath this appearance of

vitality were signs of mortal illness that only a kind of medical resuscitation

could reverse. “If,” he warned, “we don’t take steps now to ensure the sur-

vival and prosperity of this beautiful city . . . in thirty years, we will see a

very rapid decline.”

1

Boutet de Monvel’s warning was part of a long lineage

of dire predictions about the capital’s imminent demise. His was a complete

condemnation of the politically potent localism, the fragmented arrondisse-

ments, the quartiers and îlots that constituted Paris in the 1950s. The text was

a clarion call for the reassertion of state power and authority. The capital was

entering a new era under the Fifth Republic and the presidency of Charles

de Gaulle.

Despite Boutet’s assertions about dire ailment and dismal failure, a

great deal of progress had already been made toward turning Paris into

the symbol of a vigorous French nation. A series of grand-scale modernist

redevelopment projects and monumental trophy buildings was radically

reshaping the notion of urban place. Their uncompromising, vanguard de-

signs made no concessions to the scale and particularities of the historic

city. The first phase of the business complex at La Défense was under way,

with a projected completion date of 1973. “The tourist of 1973,” Boutet

predicted, “will be able to stand in the courtyard of the Louvre and look

conclusion

342 | conclusion

out through the arches of the Carousel and the Étoile to the heights of

La Défense and a 250-meter high tower” designed by Bernard Zehrfuss

that would complete the sight line. Just next to La Défense, at Nanterre,

Le Corbusier was working on designs for a cultural complex that would

include a museum, a new music conservatory, and an architecture school.

The old railroad yards at Maine-Montparnasse were being transformed into

a business center and commercial mall with a 185-meter high tower, to be

completed by 1969. The UNESCO building, designed by Bernard Zehrfus,

Marcel Breuer, and Pier Nervi and located on the place de Fontenoy, was

inaugurated in 1958 as a symbol of the city’s role in international affairs, as

was the NATO command center at the porte Dauphine. The headquarters

of state media conglomerate ORTF, or the Maison de la Radio, was com-

pleted by 1963 by the French architect Henry Bernard in high-modernist

idiom on the quai de Passy. Across the river at the Front de Seine, Ray-

mond Lopez and Michel Holley were designing a project for a “true capital

district” centered on 20 thirty-story towers (eventually cut back to 15 tow-

ers) and a six-hectare raised platform dalle that cascaded down five levels.

For the redevelopment of Les Halles, also on the drawing board, the two

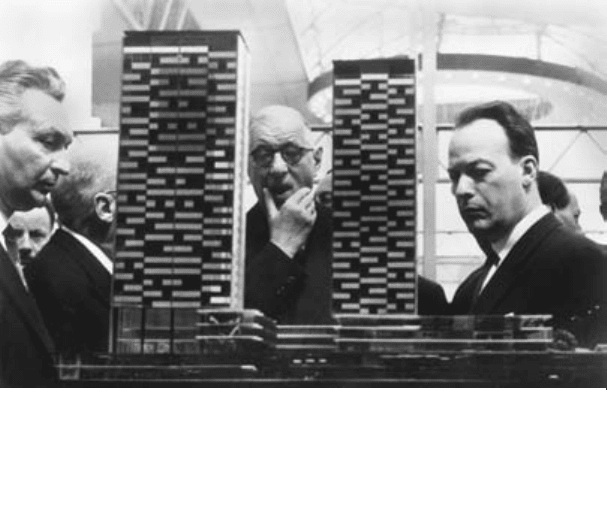

figure 34. President Charles de Gaulle and Pierre Sudreau (on his right) visiting the

exhibit “Demain . . . Paris” Exposition at the Grand Palais, before the scale model of the 15th

arrondissement, April 17, 1961. © keystone-france

constructing the paris of tomorrow | 343

imagined a colossal modernist “world trade complex” with a soaring of-

fice tower alongside Saint-Eustache Church. It was one of many futuristic

visions for the old “guts” of Paris. All of these projects were emphatically

internationalist in style. They were presented with enormous fanfare at the

“Demain . . . Paris” Exposition organized by the Ministère de la construc-

tion at the Grand Palais in 1961. Theatrics and melodramatic display had

shifted from le peuple to glamorous architecture. High-modernist designs

were triumphs of technocratic planning, an expression of the instrumental-

ity of state power and late twentieth-century capitalism. They were forms of

political communication and propagandistic illusions of power. De Gaulle

was remaking Paris into the de facto capital of Europe.

In 1961 de Gaulle appointed Paul Delouvrier as the head of the new

far-flung district of Paris. Delouvrier’s investiture heralded a radically new

climate of regional planning. A strategic plan laid out a vast network of grand

ensemble public housing projects, suburban “new towns,” highways, and re-

gional express trains. The entire emphasis in planning discourse shifted away

from the venerated zone cristalisée of the historical districts to a far-reaching

vision of the metropolitan region. Far from embracing the decentralization

policy that threatened the lifeblood of the capital, Delouvrier anticipated the

redistribution of a growing population, along with their housing and jobs,

away from the central city and into an economically robust Île-de-France.

Grand-scale modernism would go hand in hand with a new prosperity. Rather

than a jumble of fragmented pieces, urban topography was now imagined as

a broad, integrated, and rationalized ensemble. The state’s understanding of

urbanism was progressively configured around specific definitions of habitat

norms, quantitative gauges of well-being, predictions about traffic flow, and

the application of rational master-planning techniques. Data processing and

a mountain of documents evidenced conditions and statistically measured

patterns of activities and land use. These became the standard measures

of quality of life in French cities and provided the rationale for an ongoing

process of reform and regulation. This was an engineering-based systems

approach in which planning was seen as a continuous process of control and

monitoring. The spatial scale was monumental.

Private life was reified, social life continually supervised. The image of

Paris began to depend less on what local residents produced than on what

visitors consumed at the various sites developed for their pleasure. The ideal

of the city’s enchantment, its intimate scale, and its spatiality became fixed,

344 | conclusion

stagnant concepts. Carefully selected historical imagery obscured existing

social distinctions and the memory of recent political struggles while paving

the way for a new kind of antidemocratic politics. Display began to eclipse

debate as a staple of the public sphere. This had little to do with the loose

urban textures, the jumble of neighborhoods and fluid sociability, once as-

sociated with public space. Instead, citywide events encouraged Parisians and

tourists alike to participate in the public life of the city as an undifferentiated

crowd and as consumers of a shared commercial culture.

However, from the late 1940s through the end of the 1950s, the city was

the terrain of poetic humanism. It emerged as a cohesive intellectual ethos

that attempted to mediate the transformation of the trente glorieuses. As a

movement, it was powerful, wide-ranging, and porous. Concentrating on

poetic humanism as a midcentury discourse provides the opportunity to re-

think twentieth-century chronologies. It breaks down the boundary of 1945

as the traditional opening onto a distinctly new era. The origins of poetic

humanism clearly lay in the prewar years. It was heavily influenced by the

experience of war, and especially by the Resistance and Liberation, which it

claimed as its own. It is my hope that this volume adds to a growing body of

scholarship that reconceptualizes the mid-twentieth century as a significant

period in its own right. Particularly in the case of Paris, focusing on human-

ism as a counterdiscourse moves us away from treatments of midcentury

urban culture and spatiality as only a shadow of their former selves, as empty,

as mesmerized and emaciated by capitalism’s bewitching spell. It also turns

away from notions of urban planning as feeble or defeated.

Instead, what we find is a rich public sphere, made even more dramatic

by visual media. It was multiform, emotive, composed of a variety of publics

and counterpublics. In no way was the public sphere politically and socially

neutralized by media spectacle or commodified private ideals. The postwar

reconstruction years were a transformative moment, a theatrum mundi. The

streets overflowed with activity. Traditional uses of public space resurfaced

alongside new forms of civic life. Street fairs, student processions, the fête de

l’humanité, contended with endless commemoration ceremonies, with tele-

vision and radio shows broadcast live as well as with riots, violent protests,

and political marches. The phantasmagoria of the city’s public atmosphere

continued unabated and took on new, mediatized forms. There was never

really a single, defined moment at which Paris turned into pure spectacle.

Its public sphere has always been punctuated by multiple meanings, lay-

constructing the paris of tomorrow | 345

ers of action and counteraction, and creative materialization of urban life.

Even as the city became a carefully controlled touristic dream in the 1960s,

strikes and protests continued, culminating in the 1968 revolt. Entitlement

to public space was transmittable and invigorating. Various social groups

were successful in appropriating and adding to the endless vocabulary of im-

age manipulation as effective civic engagement. These practices dramatized

authentic conditions, real hopes, and, during the late 1940s and 1950s, the

extraordinary collective power of liberation and postwar renewal.

In humanist discourse, Paris was imagined as a decidedly populist, work-

ing-class place. This idealization of the proletariat was immensely powerful,

an expressive salve for the wounds that had torn France apart during the

war and occupation. The place of action for this heroic peuple was the public

spaces of the city. Space was imagined as decentered, spreading across the

landscape in a jigsaw puzzle of localized places and lived experience. Rather

than adhering to the systemic and centralizing practices of modern urbanism,

the city broke apart. It became “humanized” and sensual, encrusted with the

social practices that took place there. In humanist discourse, the neighbor-

hood was a fragmented, autonomous zone where the spirit was free from

centralizing control. It was a place of whimsy that created a mutable, fluid

spatiality and temporality, what Michel de Certeau referred to as “spatial

stories”—the everyday stories of moving through the city. For de Certeau, to

practice space is to repeat the joyful activity of childhood and “a way of moving

into something different.”

2

Folk festival and celebration were noncompliant

and subversive. Yet in this militant pedestrianism, tradition was evoked as

much as change. The uses of the past were magnified and heightened, given

mythic form. The urban fragments and objects that typify memory of place

gained significance in the quotidian atmosphere of the everyday. Memory

was an anchor in an environment of wrenching transformation.

Lastly, the destruction of the Second World War itself provoked a wide-

ranging debate about the nature of the modern city, how it should be re-

formed and reconstructed, and what forms public space should take. It gave

urban planning the quality of moral redemption. The charismatic high mod-

ernism offered by Le Corbusier and CIAM constituted the central referent

in this discourse. Yet the production of urban space is always a battlefield of

contending forces. The issue of city form is one of contradictions and spa-

tial dissonance. The spaces of the city are always malleable. Its meanings are

multiform and capable of being changed by the force of social and political