Tomlinson B.R. The New Cambridge History of India, Volume 3, Part 3: The Economy of Modern India, 1860-1970

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

TRADE

AND

MANUFACTURE,

1860-1945

Current expenditure

Year

Interest

pay-

ments

Military

expend-

iture

Civil

expend-

iture

3

Government

sterling

debt

b

1899-1900/1913-14

9-4

4-2

4-i

177.1

1914-15/1920-1

13.1

4-i

5-5

153.2

1924-5

14.4

10.1

7-4

262.5

1933-4

4-7

8.1

5-o

385.1

Note: 1899-1925, Rs 15 = £1; 1934-5, Rs 13 = £1.

a

Pensions, furlough, stores and

other

civil

expenditure.

b

Total outstanding on 31 March in end year of period (viz

31.3.14

for 1899-1900/

1913-14)

Source: Dharma Kumar, The Fiscal System', CEHI, 2, table

12.10;

Reserve Bank of India, Banking and

Monetary

Statistics of India, Bombay, 1954,

table

7

, p. 881.

because of implacable competition for scarce resources between

imperial and domestic interests. The additional difficulties for financial

and monetary policy created by India's sterling debts and payment

obligations represented a more intractable economic and political

problem in the inter-war years. The Home Charges amounted to more

than

a quarter of current government revenues by the 1930s, with

interest payments on the accumulated sterling public debt of £350

million

taking over half the total; the composition of the Home

Charges

over the first half of the twentieth century is shown in table

3.10.

Continuing the payment of interest and principal on loan capital,

and the rest of the Home Charges, was an important aim of British

policy

in India between the wars, especially during the sterling crisis of

the early 1930s when the British Government became convinced

that

it

would

have to make good these payments should India default. The

result was

that

the London authorities, at the urging of the British

Treasury, ensured

that

New Delhi followed a conservative financial

and monetary policy during the slump to retain confidence and

convertibility,

and insisted on creating 'safeguards' to guarantee

that

43

Table

3.10. Government of India expenditure and liabilities in

London, 1899-1900 to 1933-4 (annual averages in £ million)

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE

ECONOMY OF MODERN INDIA

any further constitutional reforms would not lead to a real transfer of

authority over external financial policy to an assembly of elected

politicians.

This was done by creating an independent central bank (the

Reserve

Bank of India) in 1935, which was to be accountable to the

Viceroy

rather

than

to an Indian finance minister. Once the nego-

tiations for the federal centre envisaged in the 1935 Government of

India Act ran into difficulties in the late 1930s, these arrangements

made it difficult for the colonial authorities to secure further political

support in India by new financial or constitutional concessions. No

real progress on this issue was possible until 1945, by which time the

new

system for financing India's participation in the imperial war

effort

during the Second World War had reversed the financial

relationship between Britain and India. By the end of the war all the

Government of India's pre-war sterling debt had been repaid, and was

replaced by credits in London (India's sterling balances) amounting to

over

£1,300 million.

53

The

particular interests of the colonial government required

that

its

economic

policy favour the externally oriented sectors of the local

economy

at the expense of purely domestic activities. This was a

plausible position so long as it seemed likely

that

the international

economy's

influence on India was benign, or would become so with

the evolutionary growth of appropriate domestic economic institu-

tions and markets. In the inter-war years, however, this

view

became

increasingly

hard to sustain, yet the colonial government was still

inescapably

committed to securing its external obligations as a first

priority. During the

trade

depression in the late 1920s, for example, the

Government of India had to contact the currency to secure remittance

to pay the Home Charges, just at the point

that

the domestic credit

system

was undergoing a liquidity crisis associated with the onset of

the agricultural depression. Thus the actions of government to

fulfil

one arm of its imperial commitment caused further dislocations in the

domestic economy, leading to economic retardation and to widespread

social

discontent and political protest in the 1930s.

Once

the international open economy of the long

trade

boom of

1860-1929

had collapsed in the early 1930s the British raj ran out of

room to manoeuvre. The colonial administration of South

Asia

was

53

See below, pp.

16c—1.

44

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

TRADE

AND MANUFACTURE, 1860-1945

conditional on the smooth working of a domestic and international

economy

that

could supply adequate tax revenues from production,

and a foreign exchange surplus on private account. Before 1914 the

colonial

administration provided

important

linkages, through its

Council

Bill

and domestic treasury system of financial and monetary

institutions, between the Indian, British and international economies,

and was able to combine the political acquiescence of its subjects with

an export-oriented free-trade economy run on laissez-faire principles.

After

1929, however these circumstances changed fundamentally, as

global

depression and war broke down the established systems of

marketing and credit supply within India. In attempting to repair the

damage, government was sucked into a new relationship with the

domestic economy in the 1930s and, as we

will

see shortly, by the 1940s

it had to improvise new institutions to allocate scarce goods, capital

and foreign exchange among competing local interests. Operating a

government of this type required a much more sensitive and participa-

tory political system

than

the colonial administration, could provide,

and its failure to manage the economy

effectively

during the war and in

the immediate post-war period helped to intensify the nationalist and

communal passions pushing inexorably towards Partition and the

Transfer of Power. By 1947 the British were happy to abdicate their

responsibilities in South

Asia,

hoping

that

the successor governments

of

India and Pakistan had enough political skill and legitimacy to run

the interventionist economic systems

that

a century of colonial neglect

had made necessary.

15

5

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CHAPTER

4

THE

STATE

AND THE

ECONOMY,

1939-1970:

THE

EMERGENCE

OF

ECONOMIC

MANAGEMENT

IN

INDIA

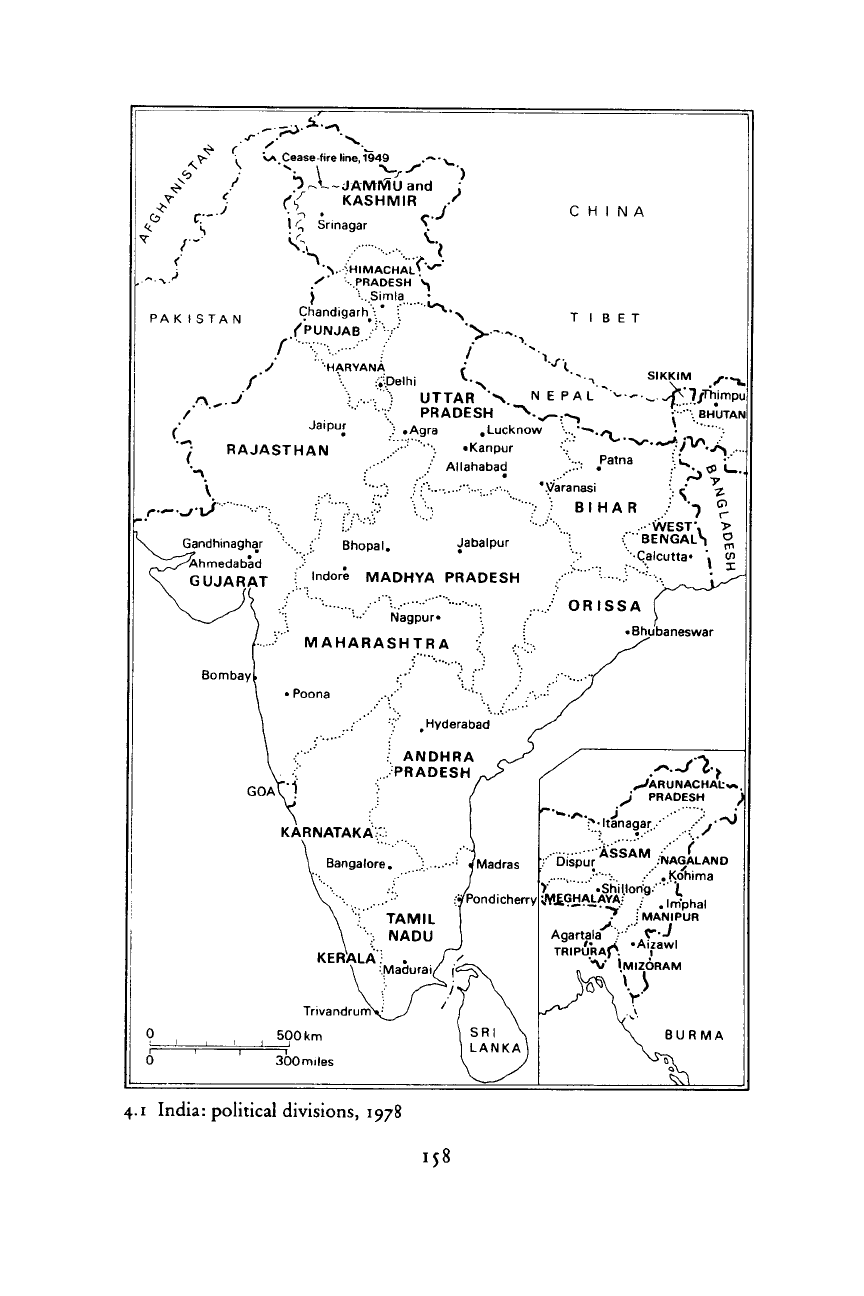

The

independent India

that

came into existence on 15 August 1947 was

a large, diverse and poor country

that

inherited many economic

problems from its colonial past. It was operating within novel political

boundaries, and the separation of sizeable areas of the north-western

and north-eastern areas of British India to create the new

state

of

Pakistan created some important economic difficulties and dislo-

cations,

especially in the supply of Punjabi wheat and Bengali jute. The

Indian Union had a federal constitution, with powers over economic

policy

split between the central government in New Delhi and the

state

administrations. In several

parts

of the country, notably in central and

western India, the administrative units were made more unwieldy by

the problems of incorporating the old Princely States into the new

administrative system, and of meeting demands for the creation of

linguistically

based states out of the old provincial administrative units

of

British India. This process continued throughout the first thirty

years

of Independence, resulting in the boundaries and units shown on

the political map of contemporary India in map 4.1. The Indian

economy

at Independence was, as we have already seen, largely

agricultural, with over four-fifths of the population

living

in rural

areas, and only about 10 per cent working in the manufacturing sector.

The

economy was also strongly regionalised, with important differ-

ences

in resources and sectoral distribution in different

parts

of the

country. Some indicators of the regional diversity of the economy in

the early 1950s are

given

in table

4.1,

while map 4.2 shows the sectoral

distribution of the labour force and per capita income for the whole

subcontinent in 1961.

The

most decisive break with the past

that

was achieved in economic

matters by independent India was in the role of government policy and

state

agencies in the running and directing of the economy. Since the

announcement of the First

Five

Year

Plan in 1952 the Indian economy

has been subjected to a regime of strict controls and close economic

management. This extensive web of government regulations has been

156

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

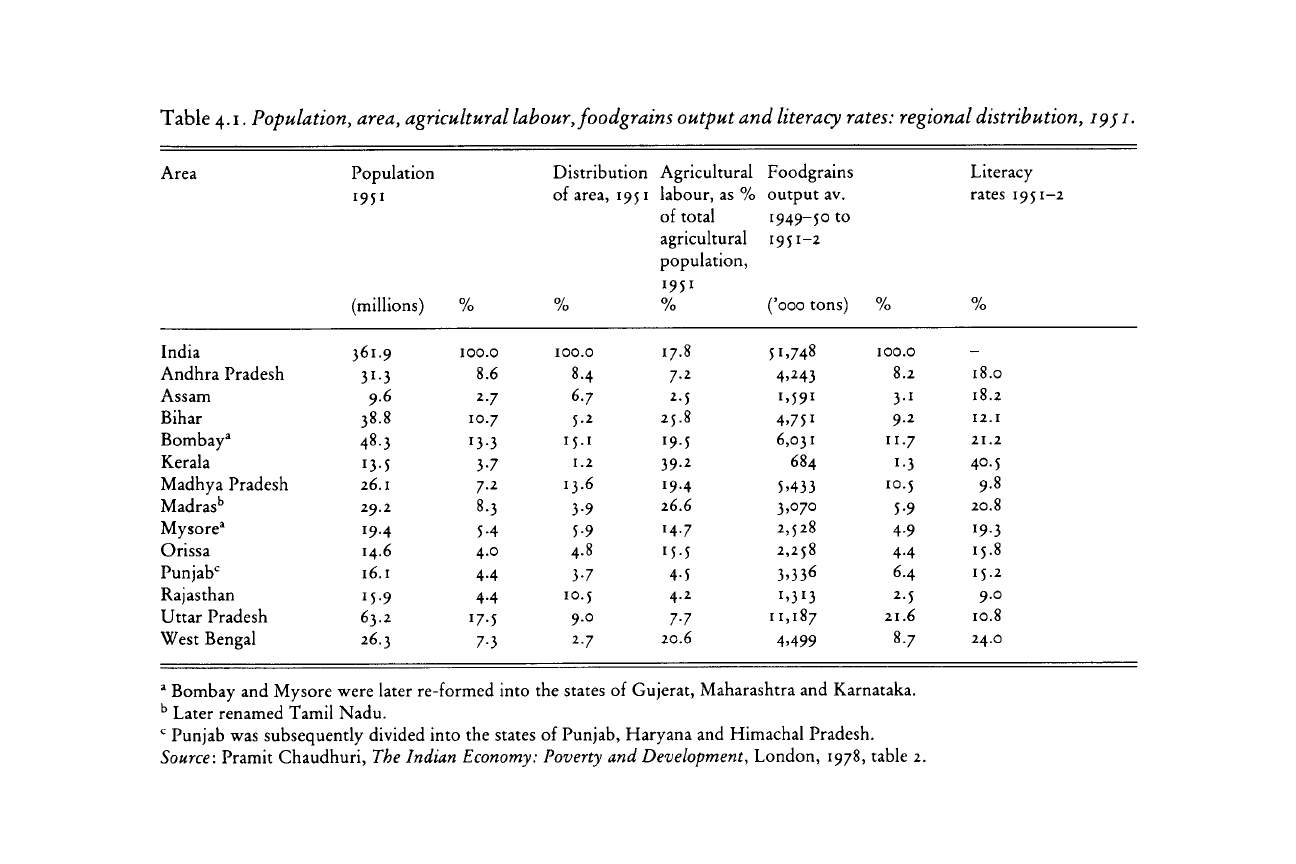

Table

4.1.

Population, area, agricultural labour, foodgrains

output

and literacy rates: regional distribution, 1951.

Area

Population

Distribution Agricultural

Foodgrains

Literacy

1951

of

area,

1951

labour, as %

output av. rates

1951-2

of

total

1949-50

to

agricultural

1951-2

population,

1951

(millions)

/0

/0

%

('000 tons)

0/

/0

%

India

361.9

100.0

100.0

17.8

51,748

100.0

-

Andhra

Pradesh

3i-3

8.6

8.4

7-2

4^43

8.2

18.0

Assam

9.6

6.7

*-S

i,59i

3-i

18.2

Bihar

38.8

10.7

S-2

25.8

4,75*

9-2

12.1

Bombay

3

48.3

13-3

15.1

19-5

6,031

11.7

21.2

Kerala

13-5

3-7

1.2

39-2

684

i-3

40.5

Madhya

Pradesh

26.1

7-2

13.6

19.4

5,433

10.5

9.8

Madras

b

29.2

8.3

3-9

26.6

3,070

5-9

20.8

Mysore

3

19.4

5-4 5-9

14.7

2,528

4-9

19-3

Orissa

14.6

4.0

4.8

15-5

2,258

4-4

15.8

Punjab

0

16.1

4-4 3-7

4-5

3-33

6

6.4

15.2

Rajasthan

15-9

4-4

10.5

4-2

1,313

2.5

9.0

Uttar Pradesh

63.2

J

7-5

9.0

7-7

11,187

21.6

10.8

West

Bengal

26.3

7-3

2-7

20.6

4,499

8.7 24.0

3

Bombay and Mysore were later re-formed into the states of Gujerat, Maharashtra and Karnataka.

b

Later renamed Tamil Nadu.

c

Punjab was subsequently divided into the states of Punjab, Haryana and Himachal Pradesh.

Source:

Pramit Chaudhuri, The

Indian

Economy: Poverty and Development, London, 1978, table 2.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

So

/

<

<

PAKISTAN

VA

Cease-fire

line,

1949

)

JAMltfU

and .

KASHMIR

I

Srinagar

\

^

^

V>HIMACHAO ^"

-..PRADESH

^

\ \. Simla.

•

Chandigarh':"

| ^^'"N

^PUNJAB

V V- - .

•HARYANA

^

UTTAR^«N. N

E

PAL^W.^.^l/Thi

PRADESH

"V^^ "

Agra .Lucknow

\-/"*«/^

CHINA

TIBET

¿\Delhi

Jaipur

RAJASTHAN

SIKKIM

\

S'

impull

BHUTAN

I

Gandhinaghar

"^hmedabâd

GUJARAT

Bombayl

Bhopal.

•Kanpur

Allahabad

Jabalpur

.

Pa,na

i

V.

*, Jl

'.Vara nasi

BIHAR

Indore

MADHYA PRADESH

Nagpur»

MAHARASHTRA

• Poona

. Hyderabad

goaY'1

karnataka:;:

Bangalore.

J

i %

.

WEST\

>

(BENGALS

%

'•Calcutta*

', </>

l

x

OR ISSA

• Bhubaneswar

^ARUNACHAL'^.

J

PRADESH

)

J

">•

Itanagar

/'y

•

Dispur ^

SAM

."NAGALAND

/' .Kohima

Y .ShillonW"" '/

^GHA^AYA/

#|r

H

pha|

J

JMANIPUR

Agartala

.

TR.PURAf\

,A,

,

ZaWl

"V

I.MIZÒRAM

\

\

Y

4.1

India:

political

divisions,

1978

158

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

- 2008 — 2025 «СтудМед»