The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 1: Ancient Japan

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

THE YAYOI PERIOD 107

yet organized their social life around the cultivation of

rice.

The strong-

est federation, located in the Nara basin of central Japan, subsequently

developed into the Yamato state, whose leaders figured prominently in

the history of Japan and buried their predecessors in huge mounds

(kofun.)

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CHAPTER

2

THE YAMATO KINGDOM

The Yamato kingdom appeared on the Nara plain of central Japan

between about

A.D.

250 and 300 and, during the next three centuries,

passed through successive stages of vigor, expansion, and disruption.

Because its "great kings"

(dkimi)

1

were buried in large mounds, these

years are commonly designated the Burial Mound {kofun)

2

period.

That was when farmers converted vast tracts of virgin land into rice

fields;

immigrants from northeast Asia introduced advanced tech-

niques of production from the continent; soldiers rode horses and

fought with iron weapons; armies subjugated most of Japan and ex-

tended their control to neighboring regions on the Korean peninsula;

and kings dispatched diplomatic missions to distant courts of Korea

and China. But because no written Japanese records of that day have

been preserved, and Korean and Chinese accounts do not tell us much

about contemporary life on the Japanese islands, the Yamato period

has long been considered a dark and puzzling stretch of prehistory.

Until the close of World War II, Japanese historians tended to think

of this period as a time when the "unbroken" imperial line was mysteri-

ously and wondrously formed. But postwar scholars have discovered

new written evidence, seen historical significance in massive archaeo-

logical finds, and viewed the whole of ancient Japanese life from differ-

ent angles. Egami Namio, for example, used Korean sources and the

findings of archaeologists to develop the thesis that in this period

1 The Yamato rulers were called "great kings," a literal translation of the word

dkimi

found in

two fifth-century inscriptions, on a sword found in the Eda Funa-yama burial mound in

Kumamoto Prefecture and on a sword excavated from the Inari-yama burial mound in Saitama

Prefecture. Although we have no proof that the word was used during earlier years of the

Yamato period, the construction of huge mounds in the southeastern corner of Yamato after

the middle of the third century suggests the appearance of rulers who may well have been

called something like dkimi. Not until the Taiho code of 701 do we have evidence that a

Japanese ruler was called an emperor or empress

(tenno).

See Kamada Motokazu, "Oken to be

min sei," in

Genshi

kodai,

vol.

1

of Rekishigaku kenkyu kai and Nihonshi kenkyu kai, eds.,

Koza:

Nihon

rekishi

(Tokyo:

Tokyo daigaku shuppankai, 1984), pp. 233-4.

2 The word

kofun

(ancient mounds)

is

commonly applied only to the huge burial mounds built in

Yamato after the middle of the third century. Archaeologists have, however, found earlier

mounds to which they refer as

funkyu-bo

(knoll mounds).

IO8

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE YAMATO KINGDOM 109

Japan came to be ruled by horse-riding warriors who had invaded the

islands from north Asia,3 and Ishimoda Sho reexamined ancient

sources and found a heroic

age.*

But our knowledge of what was really

occurring between the rule in the third century of Queen Himiko

(reported in the

Wei chih)

and the reign from 592 to 628 of Empress

Suiko (who reestablished relations with China) continued to be quite

hazy and imprecise.

Much new research has been done in the last two or three decades,

permitting us to see at long last the general outlines of a process by

which clan control in the third century was replaced by a sinicized,

bureaucratic state in the seventh century. Probably no other period in

Japanese history has been subjected to so much illumination in such a

short time. The new light has come from a number of directions.

First, numerous historians - freed from prewar restraints against the

critical study of Japan's sacred origins - have analyzed eighth-century

chronicles, attempting to distinguish myth from history and to assess

interactions between the two.5 Other historians have looked closely at

diverse sources and seen the rise and expansion of Yamato from a

"broad East Asian perspective.

6

Religious historians, mythologists,

3 Egami Namio, in his Kiba

minzoku

kokka (Tokyo: Chuokoronsha, 1967), used archaeological,

mythological, and historical data on early non-Japanese peoples of northeast Asia to support

his conclusion that Sujin was a Korean king who invaded Japan with horse-riding soldiers

during the first half of the fourth century and that the Yamato state was founded in the last half

of the fourth century when the Kyushu center of power was moved to central Japan. His basic

thesis has been further developed, with an extensive use of Korean sources, by Gari Ledyard

in "Galloping Along with the Horse-Riders: Looking for the Founders of

Japan,"

Journal of

Japanese Studies 1 (1975): 217-54. Recent archaeological investigations of ancient mounds

located in southeastern section of the Nara plain suggest that Yamato came into existence long

before the final years of the fourth century, but they provide no convincing evidence that this

kingdom was created by foreign invaders. This and other weaknesses of the Egami thesis were

revealed in Walter Edwards, "Event and Process in the Founding of

Japan:

The Horserider

Theory in Archaeological

Perspective,"

Journal of Japanese Studies 9 (Summer 1983): 265-95;

and in Edward Kidder, Jr., "The Archaeology of the Early Horse-Riders in Japan," Transac-

tions

of

the

Asiatic Society of Japan 20,3rd series (1985): 89-123. Egami nevertheless sharpened

interest in continental cultural influence on Japanese life during the Yamato period.

4 In his Nihon no kodai kokka (Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 1971), Ishimoda Sho concluded that

Japan's heroic age came between the third and fifth centuries. Ishimoda made important

contributions that have been clouded by disputes over the definition of terms and periods and

overshadowed by massive amounts of new archaeological data.

5 Ueda Masaaki provides an excellent summary in his Okimi no seiki, vol. 2 of

Nihon

no

rekishi

(Tokyo: Shogakkan, 1975). Important studies can be found in Kodai, vols. 2-4 of Asao

Naohiro, Ishi Susumu, Inoue Mitsusada, Oishi Kaichiro, et al., eds., Iwanami koza: Nihon

rekishi

(Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 1975-76). Cornelius J. Kiley carefully analyzed kinship and

state development in his "State and Dynasty in Arcahic

Yamato,"

Journal

of Asian Studies 33

(November 1973): 25-49.

6 A pioneer work is Kito Kiyoaki's Nihon kodai kokka no keisei to

higashi

Ajia (Tokyo: Azekura

shobo, 1976). Suzuki Yasutami has outlined recent studies of early Japanese history from an

East Asian perspective, in his "Ajia shominzoku no kokka keisei to Yamato oken," Genshi-

kodai, vol. 1 of Koza:

Nihon-rekishi

(Tokyo: Tokyo daigaku shuppankai, 1984), pp. 193-232.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

IIO THE YAMATO KINGDOM

and folklorists have also helped us understand that even agricultural

production and military expansion were then intertwined with the

worship of kami (deities). See Chapter 6. But by far the greatest

contributions have been made by archaeologists who have meticu-

lously investigated thousands of burial and village sites all over Japan

and compared their findings with the results of excavations made in

Korea and China.

7

Other scholars have reexamined these new data

and detected, in their search for meaning and wholeness, distinct

patterns of social and cultural change.

8

Utilizing the results of such research, we can now identify three

major currents of change in the Yamato period. The first, lasting for

around 150 years, took place when the Yamato kingdom flourished.

The second, with its high tide appearing in the

fifth

century, came when

the expanding power of the Yamato kings was manifested in overseas

military campaigns, in the construction of impressive mounds contain-

ing iron weapons and horse gear, and in the development of extensive

irrigation systems. The third current, coming in the turbulent sixth

century, arrived when Yamato's

kings,

faced with setbacks at home and

threatening situations abroad, became preoccupied with such imported

administrative techniques

as

reading and writing, bookkeeping and the

registration of householders, and higher forms of Chinese learning.

YAMATO VIGOR

Although the Yamato kingdom seems to have had no official relations

with Chinese or Korean courts during its first century and a half of

vigorous growth, evidence from archaeological sites reveals deep and

wide-ranging continental influence.

The situation in

northeast

Asia

After the breakup of the later Han empire in

A.D.

220, a number of

short-lived kingdoms arose in different regions of

China.

Two were in

contact with queens who ruled petty states in western Japan before the

rise of Yamato in central Japan: the kingdom of

Wei

(221 to 265) that

exchanged missions with the famous Himiko, and the Western Chin

(265 to 317) that was in contact with Himiko's female successor. But

7 Major studies of the last decade are listed in the archaeology sections of An Introductory

Bibliography for Japanese Studies (Tokyo: Japan Foundation, 1974-84), vols. 1-4, pt. 2.

8 An especially valuable recent study is Shiraishi Taiichiro's "Ninon kofun bunka ron," in

Genski-kodai, vol. 1, pp. 159-232.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

YAMATO VIGOR III

the collapse of Western Chin at about the time Yamato came into

existence was hastened by invasions of nomadic tribes from the north,

a disruption that was followed by the rise and fall of one kingdom after

another and that continued until the close of the sixth century. For the

last two or more centuries of the Yamato period, no Chinese ruler was

in a position to exchange diplomatic missions with kings as far away as

Japan.

And yet Chinese cultural achievements continued to affect Japanese

life in fundamental ways. Political dislocation within China may have

accelerated the outward flow of Chinese techniques and knowledge.

The incursion of nomadic tribes from the north seems to have forced

many cultured Chinese with ties to defeated regimes to seek refuge in

Korea and possibly Japan. Moreover, the destruction of Chinese colo-

nies in Korea at the beginning of the fourth century was clearly fol-

lowed by an exodus of Chinese to the islands of Japan. Although the

channels of cultural flow from China in those early years cannot be

accurately charted, it is becoming increasingly clear that most conti-

nental advances were introduced through Korea. Still, the imports

were definitely Chinese in origin and character. It is thus generally

agreed that in these first years of the Yamato period, as well as in

earlier and later times, Japan lay within the Chinese cultural orbit.

In

313,

just four years before the collapse of the Chinese court of the

Western Chin, the old Chinese Lo-lang colony in north Korea was

destroyed by Koguryo, the first of the three independent Korean

kingdoms to emerge during the fourth century. Shortly after that,

Paekche became prominent in the southwest, having amassed enough

military power by 371 to invade Koguryo, enter the enemy capital,

and kill its king. But Koguryo survived and became stronger. After

being subjected to this humiliating defeat, Koguryo introduced forms

of Chinese learning and control (Buddhism, Confucianism, and Chi-

nese penal and administrative law) similar to those that, about two

hundred years later, transformed the upper layers of Japanese society.

Then during the last half of the fourth century, a third Korean king-

dom appeared. This was Silla, the closest of the three to Yamato, on

the southeast part of the peninsula.

Very little is known about political or military relations between

these Korean kingdoms and Yamato during the first half of the fourth

century, but in 414 a stone monument was erected in north Korea, on

which was inscribed an eighteen-hundred-character memorial to King

Kwanggaet'o of Koguryo who had died the previous year. The inscrip-

tion's middle section, in which the king's exploits are detailed, con-

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

112 THE YAMATO KINGDOM

tains praise of his 399 victory against Japanese invaders. Although

there is considerable disagreement about what was actually written

and meant there - some scholars even claim that Wo (Japanese: Wa)

did not refer to people residing on the Japanese islands - the reference

suggests that Yamato had gained enough strength by the end of the

fourth century to dispatch armies across the Tsushima Straits to Ko-

rea.

9

Overseas military activity of this type is corroborated somewhat

by traditions and myths concerning a female Yamato ruler, the famous

Queen Jingu, who must have lived at about that time and who is said

to have received help and guidance from various kami while personally

leading an expeditionary force against the Korean kingdom of Silla.

10

New archaeological data provide convincing evidence that many

areas of cultural life on the Japanese islands were being profoundly

altered at that time by innovations introduced through the Korean

peninsula, giving the entire Yamato period a Korean and northeast

Asian coloration that is clearly seen in artifacts, burial practices, ritu-

als,

myths, and language, a coloration surely not created by sporadic

military expeditions or diplomatic missions alone but by sizable migra-

tions as well. Therefore when concluding that Japan lay within the

Chinese cultural orbit in that early part of the Yamato period, as well

as before and later, one should remember that contact with the Chi-

nese center was mainly through the sinified kingdoms of Korea.

Ancient mounds

Because our principal source of information about Japanese life during

the Yamato period comes from burial mounds built for deceased lead-

ers,

historians have given special attention to their nature, contents,

and distribution. Scholars who have studied burial practices all over

the world note, first, that large mounds were constructed for deceased

rulers in other parts of the world when and where kingdoms were

emerging under hereditary rule. In China, for example, huge mounds

9 See Ueda, Okimi no seiki, pp. 191-205 for a review of evidential problems. Lee Chin-hui,

"K6tai-6 hi to shichishito," in Kodai Nihon to

Chosen

bunka (Tokyo: Purejidentosha, 1979),

pp.

95-132, criticized traditional Japanese interpretations; Takeda Yukio reexamined earlier

views in "Kokaido-6 hibun shinbo nenjo no saigimmi," in Inoue Mitsusada hakushi kanreki

kinen kai, ed., Kodai shi

ronso

(Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kobunkan, 1978), vol. 1, pp. 48-84.

10 The Nihon shoki devotes Book 9 to her reign, Sakamoto Taro, Ienaga Saburo, Inoue

Mitsusada, and One Susumu, et al., eds., Nihon koten bungaku laikei (hereafter cited as

NKBT) (Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 1967), vol. 67, pp. 330-61. W. G. Aston, trans., Nihongi,

Chronicles

of Japan from

the Earliest Time to

A.D.

6*97

(hereafter cited as Aston) (London: Allen

& Unwin, 1956), pt. I, pp. 224-53. The Kojiki treatment is in bk. 2, NKBT 1.229-38;

translated by Donald L. Philippi, Kojiki (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, and

Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press, 1968), pp. 262-71.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

YAMATO VIGOR 113

were erected as early as the closing years of the Spring and Autumn

period (721 to 481 B.C.). In Korea, too, they were constructed for the

burial of kings who ruled each of the three kingdoms that arose and

flourished in the fourth century A.D., just when Yamato was expand-

ing under rulers who built enormous mounds for their deceased prede-

cessors. Although the mounds of each region had their own special

character, those erected in Japan and Korea (especially in Paekche and

Silla) during the fourth century were enough alike to suggest both a

parallel process of political centralization and a continuous and direct

flow of cultural imports from Korea to central Japan.

These large mounds did not suddenly appear in Japan at the begin-

ning of the Yamato period, however. Shiraishi Taichiro reports that

rather large ones were constructed on hills or knolls - a characteristic

feature of the early Yamato mounds - during the last part of the

previous Yayoi period. These were usually square in shape and sur-

rounded by moats, not unlike those found at that time and earlier in

China and north Asia. Toward the middle years of Yayoi - still a

century or so before the rise of the Yamato kingdom in central Japan -

such knoll mounds

(funkyubo)

were built in a zone extending from

Chugoku and Shikoku in the west to the Kanto plain in the north-

east.

11

Tsude Hiroshi points out that the digging of moats around

knoll mounds in middle Yayoi times had been paralleled by the prac-

tice of surrounding a village with a ditch, dirt wall, or board fence and

that this had been a Chinese custom since the disturbed centuries that

preceded the founding of the Han dynasty in 206

B.C.

Tsude surmises

that although these defenses in Yayoi Japan may have been installed to

protect a village against floods and wild animals, they were also meant

to protect the village from human enemies. Such defense works sug-

gest that individual relationships within the community were already

becoming close, and external relations tense, long before third-

century Chinese chronicles report endemic military strife on the Japa-

nese islands.

12

The knoll mounds of late Yayoi were not only quite large, ranging

between forty and eighty meters long, but had other characteristics of

a Yamato period mound. In addition to being built on a knoll or hill, a

few had the keyhole shape long thought to be a unique feature of the

later Yamato mounds. Moreover, many pre-Yamato knoll mounds had

horizontal stone cists for the burial of

one

particular person, and some

11 Shiraishi, "Nihon kofun bunka ron," pp. 161-2.

12 Tsude Hiroshi, "Noko shakai no keisei," in

Genshi-kodai,

pp. 131-6.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

114 THE YAMATO KINGDOM

were surrounded by clay tubes of

a

type later called

haniwa.

1

^

Such a

late Yayoi knoll mound has been found at the Makimuku site in

Sakurai in Nara Prefecture (quite close to the early Yamato burial

mounds) and also as far east as Ichihara in Chiba Prefecture. Some

historians are inclined to think that these large knoll mounds should

be classified as Yamato, but Shiraishi believes that they were made for

leaders at a pre-Yamato stage of centralization, for leaders who had

brought several agricultural communities (possibly all those in one

valley) under their control but had not yet accumulated power and

authority equal to that of a Yamato king. And yet these earlier knoll

burials leave the impression that an ideology of hereditary control had

begun to emerge, for they were clearly places to perform rites centered

on sacred ties between living and deceased as well as between rulers

and their divine ancestors.

1

*

The Shiki

center

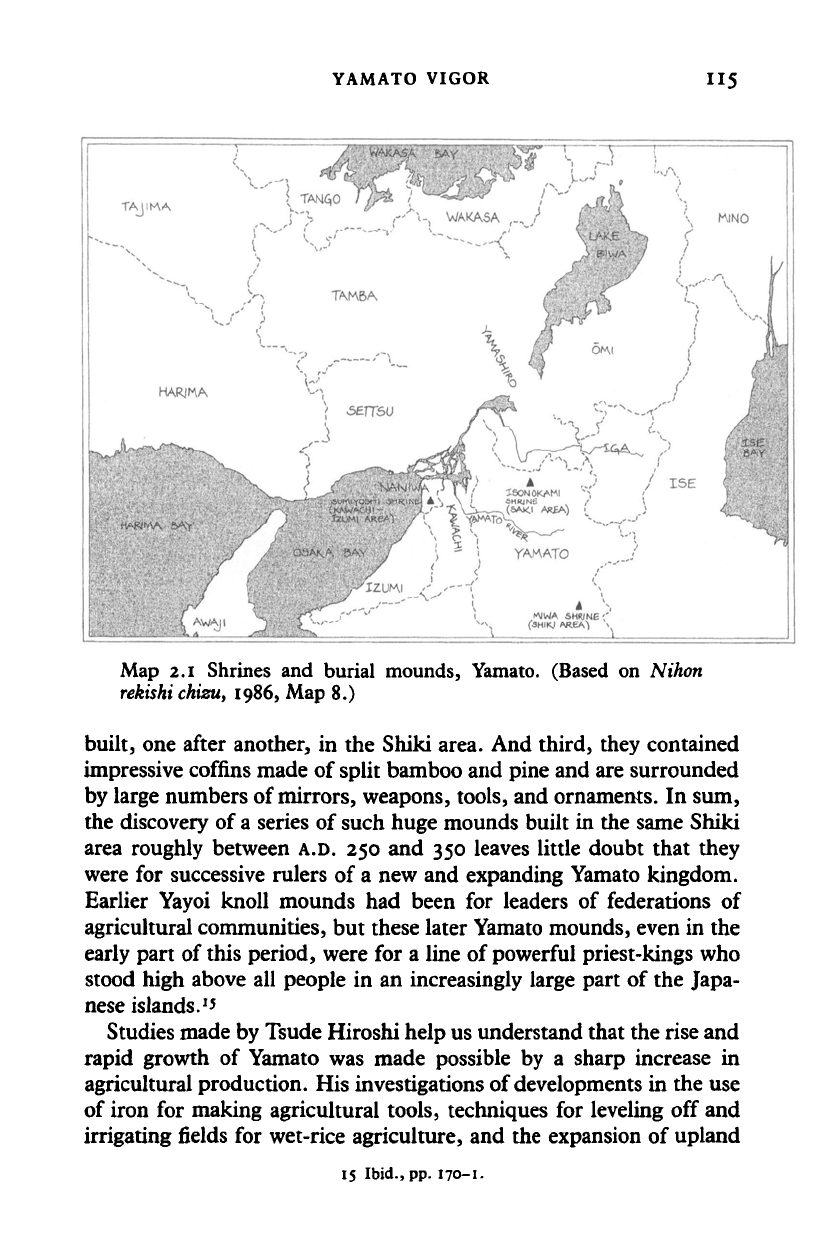

Most of what we know about the first century of the Yamato period

comes from archaeological discoveries made in the southeastern corner

of the Nara plain, in the Shiki area at the base of Mt. Miwa (see Map

2.1).

These discoveries were made largely at, or in the neighborhood

of, six mounds built between about

A.D.

250 and 350 and in the

following order: (1) the Hashihaka in the city of Sakurai, 280 meters

long; (2) the Nishitonozuka in the city of Tenri, 230 meters; (3) the

Tobi Chausu-yama of Sakurai, 207 meters; (4) the Mesuri-yama of

Sakurai, 240 meters, (5) the Ando-yama (now referred to as the Sujin

tomb) in Tenri, 240 meters; and (6) the Shibutani Muko-yama (known

as the Keiko tomb), 310 meters. Although these six mounds, like a

few earlier knoll burials, have the famous keyhole shape as well as

horizontal stone chambers, they also have other features that permit us

to associate their construction with the emergence of

the

Yamato king-

dom. First, they are exceptionally large: Each of the six is at least

twice as large as any mound found in Korea. Second, they all were

13 A spectacular pre-Yamato knoll burial was found at the Tatetsuki site near Kurashiki in

Okayama Prefecture. The main portion of the square mound is forty meters across but has

projections on opposite sides that increase its width to between seventy and eighty meters. At

the top of the mound are five stone pillars with carved surface designs, and the mound is

surrounded by two rows of rocks with small stones spread between. It was for multiple

burials but had a special place for a wooden coffin that included various jewels and an iron

sword. Kondo Yoshiro's report is summarized in Shiraishi, "Nihon kofun bunka ran," p.

162.

14 Ibid., pp. 163-5. No clear connections have been made between pre-Yamato knoll mounds

and the "country of Yamatai" mentioned in the

Wei

shu,

or between Yamatai and Yamato.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

YAMATO VIGOR

115

.v

. -

Map 2.1 Shrines and burial mounds, Yamato. (Based on Nihon

rekishi

chizu,

1986, Map 8.)

built, one after another, in the Shiki area. And third, they contained

impressive coffins made of split bamboo and pine and are surrounded

by large numbers of

mirrors,

weapons, tools, and ornaments. In sum,

the discovery of

a

series of such huge mounds built in the same Shiki

area roughly between

A.D.

250 and 350 leaves little doubt that they

were for successive rulers of a new and expanding Yamato kingdom.

Earlier Yayoi knoll mounds had been for leaders of federations of

agricultural communities, but these later Yamato mounds, even in the

early part of this period, were for a line of powerful priest-kings who

stood high above all people in an increasingly large part of the Japa-

nese islands.

1

'

Studies made by Tsude Hiroshi help us understand that the rise and

rapid growth of Yamato was made possible by a sharp increase in

agricultural production. His investigations of developments in the use

of iron for making agricultural tools, techniques for leveling off and

irrigating fields for wet-rice agriculture, and the expansion of upland

15 Ibid., pp.

170-1.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Il6 THE YAMATO KINGDOM

farming lead him to conclude that the last part of the third century was

a time of explosive agricultural growth.

16

This seems to have enabled

Yamato kings to marshal the human and physical resources needed for

constructing huge mounds, undertaking ambitious military campaigns

into distant parts of the country, and extending their control, before

the close of the fourth century, to territory as far away as the Korean

peninsula.

At the Makimuku site in the present city of Sakurai, where two of

these six burial mounds are located, pottery had been found dating

back to preagricultural times, that is, several hundred years before the

first Yamato mounds were built. About 150 meters west of these pre-

Yamato digs, archaeologists have found two irrigation ditches about 6

meters wide and between 1.3 and 1.5 meters deep in which were

several early Yamato pots.

17

Such finds suggest that stable communi-

ties had existed in this part of the Nara plain before the appearance of

the Yamato kingdom and that the rise of Yamato was indeed abetted

by a sharp increase in rice productivity resulting, in part at least, from

the introduction of improved methods of keeping rice fields flooded

during the growing season.

As has been generally true of the rise of kingdoms in other parts of

the world, the birth of

Yamato

around the last half of the third century

was intimately connected with the worship of local deities (kami),

giving the Yamato kings both sacral and secular functions. By study-

ing myths that were continuously recast and revised before existing

versions were written down at the beginning of

the

eighth century and

by searching for the meaning of materials excavated from neighboring

religious sites, historians are beginning to detect a pattern of interac-

tion between the rule of early Yamato rulers and the worship of the

kami believed to reside on Mt. Miwa.

Ancient myths and traditions indicate that Mt. Miwa was (and still

is) a sacred mountain where particularly powerful kami were wor-

shiped, and now archaeological investigations reveal that all six of

these burial mounds were built at the foot of Mt. Miwa. Even before

historians were certain that Yamato's earliest kings had any special

connection with the kami residing on Mt. Miwa, they had become

interested in the Omiwa Shrine - the major religious institution for

the worship of the Mt. Miwa kami - as this was clearly a place where

ancient rites have been preserved. These historians seem to have been

16 Tsude, "Nogyo shakai no keisei," pp.

121-31.

17 Archaeological findings are summarized in Ueda, Okimi

no

seiki,

pp. 56-87.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008