The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 06. Alien Regimes and Border States, 907-1368

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

SOCIETY

613

completion under Khubilai of the Grand Canal, the all-important economic

and political link between the Yangtze region and the capital, Ta-tu.

South China's landowners benefited greatly under the Yiian's economic

policies, except when the Tibetan Buddhist cleric Sangha (Sang-ko), as impe-

rial adviser under Khubilai in the late 1280s to 1291, initiated a campaign to

call in unpaid taxes. Once Sangha had been executed and his unpopular

financial policies reversed, south China was no longer subject to such onerous

tax collection. Thus, the southern Chinese landowning population can be

seen as an economic elite, largely left to its own devices in the Yiian period.

59

The Mongols devised household categories based mainly on occupation to

describe and keep track of both the elite and nonelite population of Yiian

China.

6

° Nonelite households that produced and manufactured goods, such

as peasant, artisan, and mining households, were mainly composed of Han

and southern Chinese, whereas Mongolian households were classified typi-

cally as military households, hunting households, and postal households.

Western and Central Asians were generally categorized as military house-

holds,

ortogh households, merchant households (not all foreign merchants

were

ortogh),

and religious households. Most of the categories were heredi-

tary, and from the Mongols' point of view, each served the state. The Mon-

gols granted tax and corvee exemptions and other privileges according to

both ethnic criteria and the relative importance of the household's occupation

to the state economy.

The granting of government stipends and exemptions from corvee and

military obligations to scholarly households (ju-hu), however, would seem to

contradict these criteria. The Mongolian emperors acquiesced to memo-

rialists' requests for favorable status for the scholarly households, most likely

in order to appease that small but important segment of the population. In

1276 the ju-hu numbered only 3,890, a small enough group for the Mongols

to waive certain of their state obligations. The number of scholarly house-

holds remained relatively low, in large part because this category of house-

hold was not hereditary; an incompetent scholar could lose his status.

At the very bottom of Yiian society were various types of

slaves.

The Yiian

period vis-a-vis earlier periods in China's history saw an increase in the

number of slaves. Historians have looked to the internal dynamics of

preconquest Mongolian society to explain this phenomenon. Although the

trend among scholars in the People's Republic of China has been to describe

the early thirteenth-century Mongols as passing through a slave-holding

59 See Uematsu Tadashi, "The control of Chiang-nan in early Yiian," Ada Aliatica, 45(1983), pp. 49-68.

60 See Huang Ch'ing-lien, Yiian lai hu chi chih tu yen chiu; Oshima Ritsuko, "The Chiang-hu in the

Yiian," Ada Asialica, 45 (1983), pp. 69—95; Hsiao Ch'i-ch'ing, "Yiian tai te ju hu: Ju shih ti wei yen

chin shih shang te i chang," in his Yiian tai shib hsin t'an (Taipei, 1983), pp. 1—58.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

614 THE YOAN GOVERNMENT AND SOCIETY

stage on the way to an early stage of feudalism in the linear Marxist scheme of

historically determined socioeconomic stages of development through which

all peoples pass, Soviet and Mongolian People's Republic scholars resolutely

hold that the Mongols skipped the slave-holding stage, thus moving directly

from a clan to a feudal society.

6l

Although these debates are not of direct

interest to us here, they do exemplify the difficulty that historians experience

in describing the role of slaves in early Mongolian society. Although the

thirteenth-century Mongols did indeed have slaves

—

usually non-Mongolian

war captives rather than indigenous slaves

—

it would not be correct to

describe slave holding as a fundamental characteristic of the Mongols' tribal

and clan-based pastoral nomadic society and economy.

Slavery was of particular importance to the economy of Mongolian soldiers

in Yuan China.

62

The Mongols kept captives from military campaigns, and

many of these captive slaves

(ch'ii-k'ou)

and their families were allocated to

soldiers for use in cultivating their lands, as Mongolian soldiers were loath to

till the soil themselves. Many of the captive slaves were Chinese, and by the

turn of the fourteenth century, so many of these captive slaves had run away

that Mongolian military households became impoverished, and ironically,

Mongolian men and women themselves began to be exported as slaves to

India and Islamic countries, starting as early as the late thirteenth century.

Although most slaves in Yuan China were thirteenth-century prisoners of

war, there also is evidence of the continuing enslavement, as well as the

buying and selling, of slaves throughout the Yuan period. Some were cap-

tives taken during internal rebellions, but others were apparently just arbi-

trary victims enslaved by officials and soldiers. Contemporary Yuan observers

deplored the existence of

slave

markets in Ta-tu, remarking that people were

being treated like cattle. To the Mongols, however, the category of

slave

was

indeed connected conceptually with ownership of animate and inanimate

objects. This is demonstrated by the existence of

the

so-called Agency of Men

and Things Gone Astray (Lan-i-chien), in which the disposition of runaway

slaves, lost material goods, and lost cattle was not differentiated.

Yuan government and society reflect both continuities and breaks with the

Chinese past. Yuan political institutions and styles of governance were based

on Mongolian, Inner Asian, and Chinese precedents, often difficult to disen-

61 See, for instance, Kao Wen-te,

Meng-ku

tin li

chih yen chiu

(Koke Khota, 1980); and Lu Ming-hui, "San

shih nien lai Chung-kuo Meng-ku shih yen chiu kai k'uang," in Meng-ku shih yen chiu lun wen chi, ed.

Lu Ming-hui et al. (Peking, 1984), pp. 240—3. On the treatment of Mongolian social development

and Yuan history in the Soviet Union and the Mongolian People's Republic, see Elizabeth Endicott-

West, "The Yuan," in Soviet

studies

of

premodem

China, ed. Gilbert Rozman (Ann Arbor, 1984), pp.

97-110.

62 See Hsiao, The military establishment of the Yiian dynasty, pp. 21, 29—30; and Tetsuo Ebisawa,

"Bondservants in the Yiian," Ada Asiatica, 45 (1983), pp. 27—48. The Japanese scholarship on slaves

in Yiian China is extensive.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

SOCIETY 615

tangle from one another. The Mongols often used Chinese means to achieve

specifically Mongolian goals (e.g., the use of the Chinese hereditary yin

privilege to maintain ethnic elites) and again used Mongolian means to

achieve goals that any dynasty on Chinese soil inevitably strove to attain (as

in the establishment of the Mongolian office of

darughachi

to oversee local

government).

The particular needs of the Mongolian ruling elite led to governing mea-

sures that probably would not have arisen indigenously. Historians of Yuan

China continue to assess the unique elements in Mongolian rule, or more

specifically, to define what constituted "un-Chinese" (actual or perceived)

ways of

governance.

Identifying, explaining, and assessing Yuan governmen-

tal institutions and social practices reconfirm for historians the distinctive

character of the era of Mongolian rule.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CHAPTER

9

CHINESE SOCIETY UNDER MONGOL

RULE, 1215-1368

THE MONGOLIAN PERIOD IN CHINESE HISTORY

The great khan (more properly, khaghan) Khubilai, who

had

taken that title

denoting supreme rule

of

the Mongolian empire

in

1260, took

a

further step

at

the end

of

the year

1271:

He

proclaimed that starting with

the

New Year,

his government

in

China would

be

called

the

Great Yuan dynasty.

He was

acting

on

the

advice

of

Chinese

and

sinified non-Chinese counselors,

and

his

proclamation employed allusive wordings from Chinese tradition supplied by

them. They devised

the

terminology

to

place

the

alien conquest dynasty

within

the

traditions

of

Chinese statecraft,

to

express

for him

benevolent-

sounding objectives vis-a-vis

his

Chinese subjects

and

their cultural tradi-

tions.

1

That gave

an

appropriate mask

to, but did not

conceal,

the

fact that

the Mongols

had

come into China

to

enrich themselves

and

sustain their

military empire beyond China. They were under pressure

to

maintain their

military

and

political superiority

in

China

in

order

to

exploit

the

resources of

the world's largest

and

richest nation. They altered their approaches

to

that

problem successively throughout

the 150

years from Chinggis khan's early

campaigns against the Jurchen Chin dynasty

in

1215 until the Mongols were

driven

out of

China

in 1368.

Khubilai khan's ceremonious adoption

of

Chinese dynastic forms

in 1272

began

the

period

of

greatest Mongolian

adaptation

to

Chinese influences

on the

patterns

of

government. Khubilai's

long

and

illustrious reign also marked

the

fullest regularization

of

Yuan

governing procedures.

But

we must note that

in not all

of

these matters

did

he accept Chinese "guidance" designed

to

detach Mongolian rule from

its

origins

in

the other body of historical experience on which the Mongols drew:

the traditions

of

the steppe and

the

norms

of

the Mongolian empire.

The Chinese

at

that time and since have nonetheless accepted the period of

Mongolian rule

as a

legitimate dynasty

in

their political tradition.

And

despite cogent reasons today

for

seeing that century and a

half,

as the Chinese

always have,

as an era in

Chinese social history, we must

not let

this obscure

1

For a

translation

of the

edict proclaiming

the

dynasty

and a

discussion

of its

significance,

see the

introduction to John

D.

Langlois,

Jr.,

ed.,

China under Mongol rule

(Princeton, 1981),

pp.

3-21.

6l6

THE MONGOLIAN PERIOD IN CHINESE HISTORY 617

for us the fact of extraordinary changes in the management of Chinese society.

We must note the consequences of those for Yuan social history and must

attempt to assess their consequences for post-Yuan history as well. In the

long-range

view,

the continuities nonetheless dominate. We

see

no fundamen-

tal displacement and redirection of the course of national history of the kind

that historians describe for Russia, induced by the Mongolian destruction of

Kiev in 1240 and the Golden Horde's subsequent domination of the Russian

state until 1480.

2

In East Asia the Mongolian conquests terminated some

histories, transformed others, and created new nations, most notably their

own.

The early years of Mongolian dominance witnessed, from 1215 to 1234,

the destruction of the Jurchen and Tangut states that lay largely within the

northern borders of China, and the dislocation or virtual extinction of their

peoples. There was nothing comparable to that

in

the case of the Chinese

nation.

It

was spared the direct onslaught of the early campaigns of con-

quest, and in any event its massive size may have buffered

it

against such

thoroughgoing dislocations. Mongolian patterns of conquest changed some-

what after the 1240s. The later Mongolian conquerors, Mongke (r. 1250-

9) and Khubilai (r. 1260-94), under whom China was brought into the

Mongolian empire, dealt with their sedentary subjects more purposively

and more effectively in the interests of the Mongolian state than had their

formidable warrior predecessors. Their policies also better served the inter-

ests of their conquered subjects; in some measure, a congruence of interests

was worked out. This

is

not to ignore the troubling departures from the

normal Chinese order of things that ensued. Eventually, however, the Chi-

nese felt that they had survived and triumphed over

an

unprecedented

disaster in the Mongolian conquest of their venerable civilization.

Apart from these externally imposed crises and the Chinese adaptation to

them, there also are cogent arguments to support the idea that the Yuan

dynasty coincided with a watershed in Chinese historical development. Some

of the net changes in Chinese civilization evident by the end of the period,

particularly in the realms of government and statecraft thought, can be seen

as culminations of trends long present in China, though enhanced by the

special conditions of Mongolian rule. On the other hand, we must also take

2 Charles

J.

Halperin,

Russia

and

the Golden

Horde:

The Mongol impact on medieval Russian history

(Blooming-

ton,

198;), though not contradicting what has here been called the "fundamental displacement and

redirection of the course of history" in the case of Russia, nonetheless emphasizes cultural continuities

and sees incidental benefits

to

Russia arising out of the "Mongol impact." Halperin aims to correct

Russian historians' consistent ignoring of all good consequences of Mongolian overlordship in Russia.

In contrast, the Chinese, though critical, have tended to deemphasize the destructive aspects of alien

rule

in

China and

to

emphasize cultural continuity, nonetheless imputing the "good"

to

Chinese

cultural superiority, not to the alien presence.

6l8 CHINESE SOCIETY UNDER MONGOL RULE

account

of

the disruptive change and the varied Chinese responses to all

the

new factors introduced by the alien presence. The point of view adopted here

is that the latter, the set of circumstances directly attributable to the Mongo-

lian overlordship, accounts for much

in

both political and social history.

It

is

more difficult

to

marshal supporting evidence from the life

of

the society

at

large than

it

is from the political sphere. This chapter will attempt to suggest

the kinds of

issues

in social history that give the Yuan dynasty its interest and

importance

in

the minds of historians today.

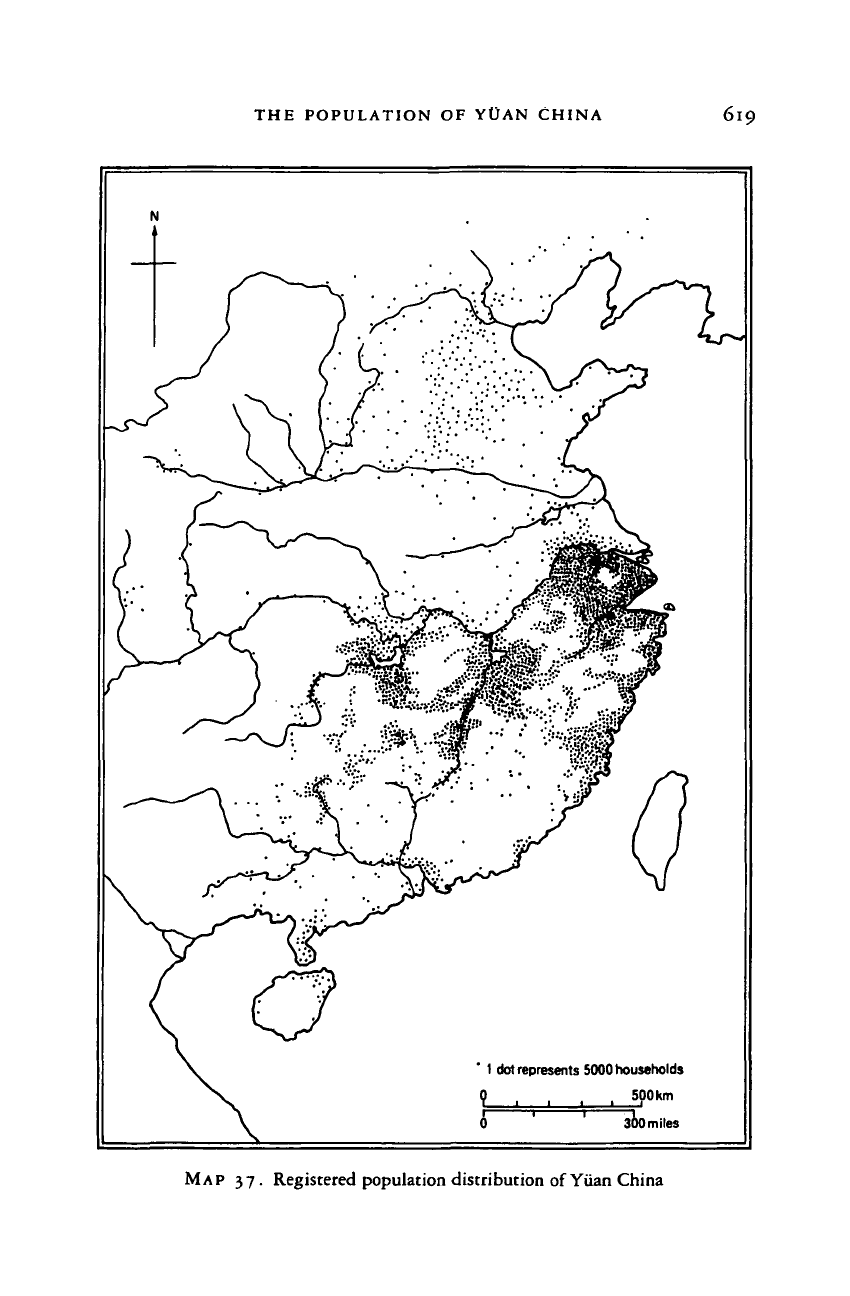

THE POPULATION OF YUAN CHINA

Some of

the

most basic facts about Yuan society remain subject to speculation

and debate. The most glaring example

is

the uncertainty about the size and

distribution

of

the Chinese population.

A

later section

of

this chapter will

show that

the

Yuan government went beyond

all

precedent

in its

effort

to

classify and register its subjects according to status and occupation,

in

order

to serve its social management objectives. The actual counting of households

and individuals, nonetheless, was less directly relevant

to the

Yuan fiscal

system than

it had

been under Chinese dynasties,

and the

administrative

machinery responsible for the census, taxation, and land registration was not

notably efficient. The quality of these data is thus more than usually suspect.

Historical demographers point

to

the figures from

a

census

in

1290, late

in

the reign

of

Khubilai khan,

as the

most reliable

of

the Yuan period.

As

reported

in

the

Yuan

shih,*

it registered 13.19 million households containing

58,834,711 persons (see Map 37).

The historians note, however, that

no

figures

are

given

for the

newly

conquered province

of

Yunnan,

for a

number of widely scattered prefectural

and county level administrative units, for people "dwelling in mountains and

marshes" and other remote places,

or for

several large categories

of

residents

such

as

monks

and

priests,

the

military,

and

households

in

bondage

to

appanages.

The only other nationwide figures from the Yuan following the conquest

of the Southern Sung are supposedly from

a

new census dated 1330; they

show

an

insignificant increase,

and

there

is

reason

to

believe that they

are

largely figures carried over from 1290,

not the

result

of

a new census.

The

number of individuals per household

in

the 1290 census

figures

is about 4.5,

low but not impossible. It seems plausible that the population of Yuan China

shortly after the conquest of Southern Sung

in

the 1270s was

in

the range of

65 million persons.

The

1290 figures closely match those provided

by the

3 Sung Lien

et

al., eds.. Yuan shih(Peking, 1976),

58, p.

1346 (hereafter cited as

YS).

THE POPULATION OF YUAN CHINA 619

1 dot represents 5000 households

MAP

37. Registered population distribution of

Yiian

China

62O CHINESE SOCIETY UNDER MONGOL RULE

best early Ming census, that of 1393, which registered 10,652,789 house-

holds and 60,545,812 individuals. There the mean household size is 5.68,

but the total of 60.5 million individuals is very close to the Yiian

figures

of a

century earlier. One long-standard work expresses the opinion that the actual

population in 1393 was larger, and it shows that fiscal considerations took

precedence in the census taking, allowing the undercounting of non-

taxpaying young children, widows, and the infirm (although that would

raise still further the ratio of individuals to households).

4

The Yiian

figures

of

1290 thus seem to be corroborated by the early Ming figures of 1393.

Our confidence in those figures is challenged by the fact that the popula-

tion of China had been substantially greater in Sung times. The Northern

Sung government in 1109 registered 20 million households (implying a total

population of more than 100 million), and the combined registered popula-

tion of Chin and Southern Sung (i.e., more or less the same area) in about the

year 1200 has been calculated to be over 100 million.' It is difficult to

believe that the population of China was reduced by one-half during the

thirteenth century and was still that low at the end of the fourteenth century

after a quarter-century of recovery from the Yiian period. Yet if we assume

that administrative laxity - meaning the inability to conduct a thorough

census - or the intentional omission of

some

groups (e.g., the captive house-

holds granted in fief to Mongolian leaders' appanages) offers an adequate

explanation for the low 1290 figures,

6

it would be reasonable to assume that

the more comprehensive early Ming figures from 1393, when administrative

rigor was in force, would show a marked increase. At least, one could assume

that the household figure was closer to reality, even if the counting of

individuals was skewed by

fiscal

considerations. Instead, they corroborate the

1290 figures. Although none of these census registrations should be inter-

preted as the result of a thorough attempt to count all the individuals in

China, as their purpose was

fiscal

management and not demographic research

per se, it is probably true that they indicate the general contours of popula-

tion increase and decrease and of distribution. Thus one must assume that

there was a catastrophic reduction in China's population between 1200 and

1400,

the most extreme in the history of China.

A closer look at some of

the

figures

strengthens that assumption. The Chin

dynasty's registration of 1207 gives a total population - essentially that of

China north of the Huai River - of 8.4 million households containing 53.5

4 Ho Ping-ti, Studies on

the population

ofChina, 1368-1953 (Cambridge, Mass., 1959), pp. 10—12.

5 Ho Ping-ti, "An estimate of the total population of Sung-Chin China," in Eludes Song in

memoriam

ttienne Balazs, 1st series, no. i, ed. Franchise Aubin (Paris, 1970), pp. 33-53.

6 For a discussion of census-taking procedures in the Yiian, see Huang Ch'ing-lien, Yiian tai

hu

chi Mb tu

yen chiu (Taipei, 1977), pp. 128-35.

THE POPULATION OF YtJAN CHINA 621

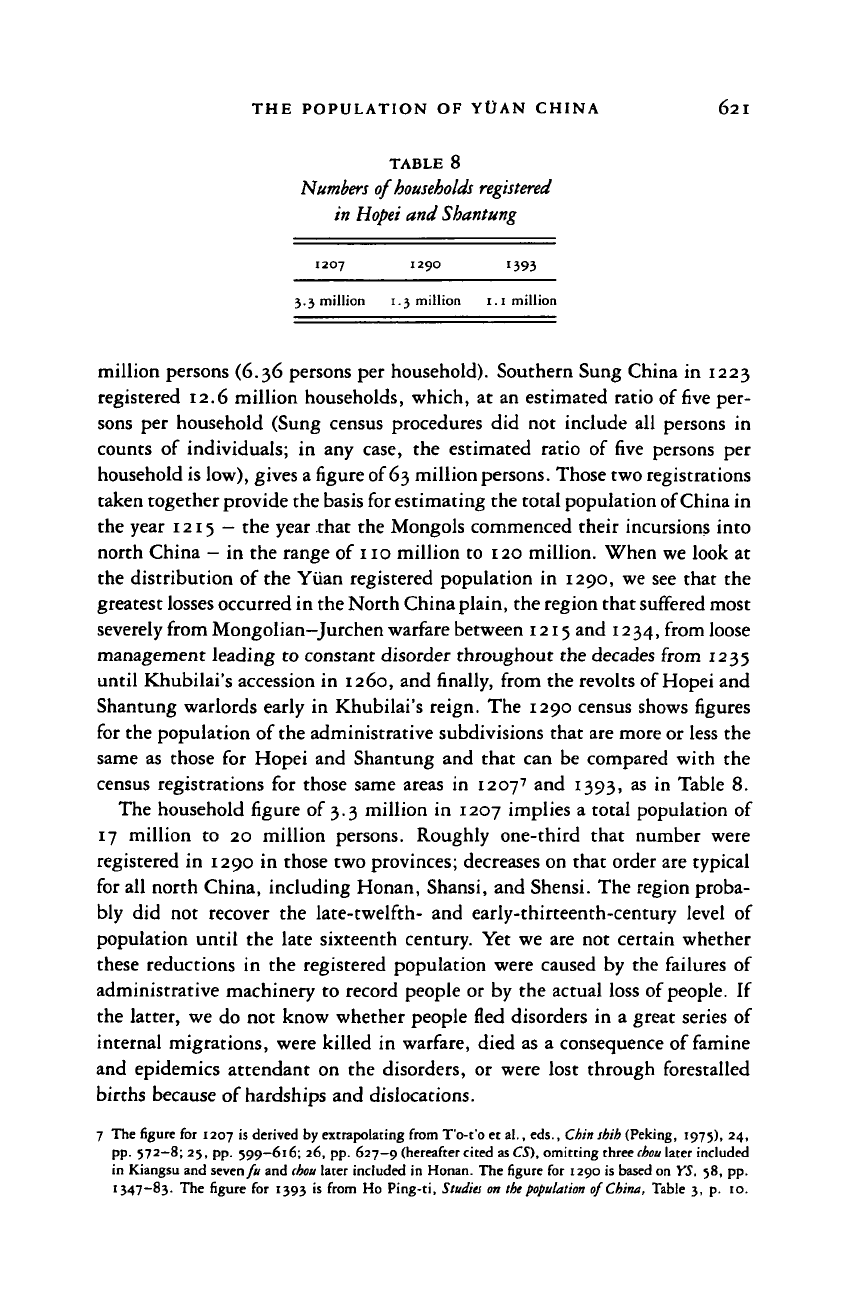

TABLE 8

Numbers of households registered

in Hopei and Shantung

1207 1290 1393

3.3 million 1.3 million 1.1 million

million persons (6.36 persons per household). Southern Sung China in 1223

registered 12.6 million households, which, at an estimated ratio of five per-

sons per household (Sung census procedures did not include all persons in

counts of individuals; in any case, the estimated ratio of five persons per

household is low), gives a figure of 63 million persons. Those two registrations

taken together provide the basis for estimating the total population of China in

the year 1215

—

the year that the Mongols commenced their incursions into

north China

—

in the range of 110 million to 120 million. When we look at

the distribution of the Yuan registered population in 1290, we see that the

greatest losses occurred in the North China plain, the region that suffered most

severely from Mongolian-Jurchen warfare between 1215 and 1234, from loose

management leading to constant disorder throughout the decades from 1235

until Khubilai's accession in 1260, and finally, from the revolts of Hopei and

Shantung warlords early in Khubilai's reign. The 1290 census shows figures

for the population of the administrative subdivisions that are more or less the

same as those for Hopei and Shantung and that can be compared with the

census registrations for those same areas in 1207

7

and 1393, as in Table 8.

The household figure of 3.3 million in 1207 implies a total population of

17 million to 20 million persons. Roughly one-third that number were

registered in 1290 in those two provinces; decreases on that order are typical

for all north China, including Honan, Shansi, and Shensi. The region proba-

bly did not recover the late-twelfth- and early-thirteenth-century level of

population until the late sixteenth century. Yet we are not certain whether

these reductions in the registered population were caused by the failures of

administrative machinery to record people or by the actual loss of people. If

the latter, we do not know whether people fled disorders in a great series of

internal migrations, were killed in warfare, died as a consequence of famine

and epidemics attendant on the disorders, or were lost through forestalled

births because of hardships and dislocations.

7 The figure for 1207 is derived by extrapolating from T'o-t'o et al., eds., Chin shih (Peking, 1975), 24,

pp.

572-8; 25, pp. 599—616; 26, pp. 627—9 (hereafter cited asCT), omitting three

chou

later included

in Kiangsu and seven fu and

chou

later included in Honan. The figure for 1290 is based on YS. 58, pp.

1347-83.

The figure for 1393 is from Ho Ping-ti, Studies on

the population

of China, Table 3, p. 10.

622 CHINESE SOCIETY UNDER MONGOL RULE

That the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries were a long period of repeated

disasters throughout much of north China is strongly supported by descrip-

tive information, yet the precise facts of population history cannot be derived

from that. If migration from one locality in China to another were a signifi-

cant factor, we might expect the migrants' descendants to show up in the

1393 census, but they do not. One might assume a combination of these

factors, but the net loss from warfare and calamity plus the forestalled

replacement attributable to long decades of hardship presents itself as the

inescapable conclusion. It is troubling to face a large riddle of this kind: If

modern historians cannot know with more precision about the size and

distribution of the population and the causes of its fluctuations, what can

they say with assurance about the social history of the period?

8

Although the quantitative data have so far failed to resolve the riddles of

the Yuan period's population history, fortunately the qualitative information

allows historians to come to more satisfying, though by no means undis-

puted, conclusions about the life of Chinese society under Mongolian rule.

SOCIAL-PSYCHOLOGICAL FACTORS

The Chinese people had experienced alien rule at several points in their

history, but never before over their entire nation. After a number of probing

campaigns into north China throughout the decade following acceptance of

Chinggis khan's leadership by his Mongolian and allied compatriots in 1206,

Mongolian armies first conquered the two other alien states then occupying

northern parts of China: The Tangut Hsi Hsia state in the northwest fell in

1227,

and the Jurchen Chin dynasty, whose conquest had required twenty

years,

finally collapsed in 1234. At that stage in their history

—

while their

armies simultaneously drove westward across Asia and into Europe

—

the

Mongols' goal was to defeat any nation or fortified city foolish enough to

resist them, but not to occupy and govern it. North China was repeatedly

crossed by armies and ravaged; local military leaders were often left in loose

8 A recent and thorough exploration of historical materials relevant to the Yuan population problem is

offered by Ch'iu Shu-shen and Wang T'ing in "Yuan tai hu k'ou wen t'i ch'u i," Yuan sbih lun

ts'ung,

2

(1983),

pp. 111—24. This study accepts the Yuan period registration figures just cited, proposing that

they represent a 20 percent underreporting. It then estimates that a maximum figure for the Yuan

period was reached some decades after the registration of 1290, in about 1340 and that it can be

calculated to have reached 19.9 million households and 90 million persons, figures that were reduced

again by the late Yuan warfare to 13 million households and over 60 million persons by the end of the

dynasty in 1368. This solution compounds the dilemma by proposing wide fluctuations both up and

down, without analyzing the annual rates of increase between 1290 and 1340 that would have been

necessary to produce the high estimate for 1340 or without explaining why such rates would not have

been present again in stable years after 1368. Also, it requires two catastrophic reductions in the actual

population, ranging from 33 to 50 percent, one following the peak of around 1215 and another

following that of 1340. Nonetheless, this study merits careful consideration.