Schweitzer P.A. Fundamentals of corrosion. Mechanisms, causes, and preventative methods

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Atmospheric Corrosion 149

4.8.5.1 Plywood

Wood layers or plies of veneer, or veneer and lumber in which alternate

plies are laid with the grain at right angles, are given the name plywood. By

alternating the grain direction of each ply, in adjacent plies, the two face

directions are equalized in strength, stiffness, and dimensional changes.

Plywood is produced as either interior or exterior type. Exterior-type ply-

wood is designed to retain its shape and strength when repeatedly wetted

and dried under adverse conditions and be suitable for permanent outdoor

exposure. It is sometimes referred to as marine plywood. Exterior plywood is

usually bonded with hot-pressed phenol resins.

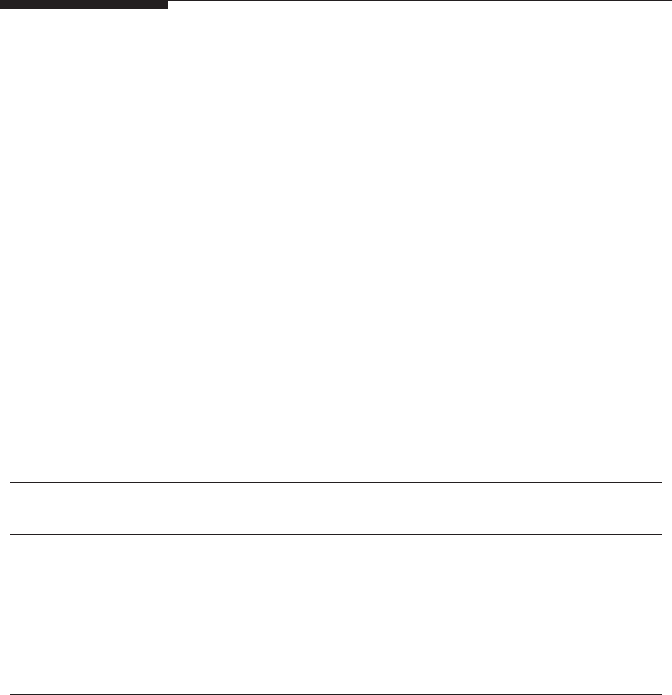

TabLE 4.23

Resistance of Wood to Decay

Softwoods Hardwoods

Bald cypress

Ε

Ash

Ρ

Douglas r

F–G

Aspen

VP

Hemlock, western

Ρ

Balsa

Ρ

Larch, western

F

Beech, American

Ρ

Pine, ponderosa

F

Birch, yellow

G

Redwood, virgin

Ε

Cherry, black

Ε

Spruce, Sitka

F

Chestnut, American

Ε

White cedar

Ε

Cottonwood, eastern

VP

Elm, American

F

Elm, rock

F

Hickory, shayback

G

Magnolia, southern

P

Mahogany

G

Maple, sugar

Ρ

Maple, silver

Ρ

Oak, red

G

Oak, white

G

Sycamore

Ρ

Sweetgum

F

Walnut, black

Ε

Poplar, yellow P

Note: Ε = excellent; G = good; F = fair; P = poor; and VP = very

poor.

Source: From Reference 23.

150 Fundamentals of Corrosion

4.8.5.2 Reconstituted Wood Products

Reconstituted wood products are produced by the formation of small pieces

of wood into large sheets. The nished product can be classied as berboard

or particle board, depending on the nature of the basic wood component.

Fiberboards are produced from mechanical pulps. Hardwood is a rela-

tively heavy type of berboard that is designed for exterior exposure.

Some reconstituted wood products can be factory primed with paint and

some may have a factory-applied topcoat to protect the wood from fungi and

insects; treatment with toxic chemicals provides the necessary protection.

A variety of materials can be used but oil and oil-borne preservatives pre-

dominate. The most widely used is coal tar creosote, which is a by-product

distilled from the coal tar produced by the high-temperature carbonization

of bituminous coal. It is a heterogeneous mixture of liquid and solid hydro-

carbons. To increase penetration and reduce the coat, coal tar solutions and

creosote-petroleum solutions are used extensively. Solutions as high as 50%

have been used. A disadvantage to this type of treatment is the inability to

apply paint.

When cleanliness and paintability are required, pentachlorophenol in vol-

atile petrochemical carriers is used. Concentrations of not less than 5% are

used. These solutions are in the same price range as coal tar emulsions and

provide the same degree of protection.

Water-borne solutions of inorganic salts are also used. These have the

advantages over the oils of greater ease of penetration and freedom from re

hazards and odor. The disadvantage is that they cause swelling and some

react with metal. The primary preservative used is chromated zinc chloride.

Other typical salts used include:

1. Acid cupric chromate

2. Ammonial copper arsenate

3. Chromated copper arsenate

4. Chromated zinc arsenate

5. Copperized chromated zinc chloride

Wood can be treated with preservatives in several ways, including:

1. Under pressure in closed vessels

2. Dipping

3. Hot and cold soak

4. Diffusion

Of the four methods listed, treatment under pressure in closed vessels is the

predominant method employed for lumber used in engineering structures.

Atmospheric Corrosion 151

4.8.5.3 Applied Exterior Wood Finishes

There are a variety of nishes that can be applied to wood that is to be

exposed to the weather and atmospheric conditions. The nish selected will

depend on the appearance and degree of protection desired and on the spe-

cies of wood to be protected. In addition, different nishes provide varying

degrees of protection; therefore, the type, quality, quantity, and application

method of the nish must be considered when selecting and planning the

nishing of wood and wood products. Table 4.24 shows the relative painting

and weathering properties of various woods. The classication of paintabil-

ity results from the nature of the specic wood. The higher the rating, the

greater the care that must be taken in applying the nishes.

Paints. Paint coatings on wood provide the most protection because they block

the damaging ultraviolet light rays from the sun. They may be either oil based

or latex based. Either type is available in a wide range of colors. Oil or alkyd

paints are borne by an organic solvent, whereas latex-based paints are water-

borne. The three primary reasons for using paints are to protect the wood sur-

face from weathering, to conceal certain defects, and for aesthetic purposes.

Paints do not penetrate the wood surface too deeply. A surface lm is

formed while obscuring the wood grain. Paints perform best on smooth,

edge-grained lumber of lightweight species. If the wood becomes wet, the

paint lm blisters or peels.

A nonporous paint lm provides the most protection for wood against

surface erosion and the largest selection of colors of any of the wood n-

ishes. Paint accomplishes this by retarding the penetration of moisture, and

reducing the problem of discoloration by wood extractives, paint peeling,

and warping of the wood. However, paint is not a preservative. It does not

prevent decay if conditions are favorable for fungi growth. Wood preserva-

tives must be used for this purpose.

Water-repellent preservatives. Water-repellent preservatives contain a fun-

gicide or mildewcide (the preservative), a small amount of wax for water

repellence, a resin or drying oil, and a solvent such as mineral spirits or tur-

pentine. A water-repellent preservative can be used as a natural nish. These

preservatives do not usually contain coloring pigments. The type of wood

determines the color of the resulting nish. The mildewcide prevents wood

from darkening.

During the rst few years of application, the water-repellent preservative

has a short life. Additional applications are usually required each year. Once

the wood has weathered to a uniform color, the treatments are more durable

and renishing is required only when the surface starts to become unevenly

colored by fungi.

Special color effects can be achieved by adding inorganic pigments to the

water-repellent preservatives. The addition of pigment to the nish helps

stabilize the color and increase the durability of the nish. Colors that match

the natural color of the wood and extractives are usually preferred.

152 Fundamentals of Corrosion

Water-repellent preservatives can also be used on bare wood prior to prim-

ing and painting or in areas where old paint has peeled, exposing bare wood.

This treatment prevents rain or dew from penetrating into the wood, partic-

ularly at joints and end-grain, thereby reducing the swelling and shrinking

of wood. This reduces the stress placed on the paint lm, thus extending its

service life.

TabLE 4.24

Painting and Weathering Characteristics of Various Woods

Woods

Ease of Keeping

Painted

Resistance to

Weathering

Softwoods

Cedar 1

A

Cypress 1

A

Redwood 1

A

Pine, ponderosa 3

Β

Fir 3

Β

Hemlock 3

Β

Spruce 3

Β

Douglas r 4

Β

Larch 4

Β

Hardwoods

Aspen 3

Β–Α

Basswood 3

Β

Cottonwood 3

D–B

Magnolia 3

Β

Yellow poplar 3

Β–Α

Beech 4

D–B

Birch 4 D–B

Gum 4

D–B

Lauan (plywood) 4

Β

Maple 4

Β

Chestnut 5–3

C–B

Walnut 5–3

C–B

Elm 5–4

D–B

Hickory 5–4

D–B

Oak, white 5–4

D–B

Oak, red 5–4

D–B

Note: 1 = easiest to keep well painted; 5 = most difcult. A = most

resistant to weathering; D = least resistant to weathering.

Source: From Reference 24.

Atmospheric Corrosion 153

Water repellents. Water repellents are water-repellent preservatives with

the fungicide, mildewcide, and preservatives omitted. They are not effective

natural nishes by themselves but are used as a stabilizing treatment prior

to priming and painting.

Solid color stains. Solid color stains provide an opaque nish and are avail-

able in a wide range of colors. They contain a much higher concentration of

pigment than the semitransparent stains. Solid color stains totally obscure

the natural color and grains of the wood. Oil-based and latex-based solid

color stains form a lm similar to a paint lm and as such can peel loose

from the substrate. Both of these stains are similar to thinned paint and

can usually be applied over old paint or stains, providing the old nish is

securely bonded.

Semitransparent penetrating stains. Semitransparent penetrating stains are

moderately pigmented and do not hide the wood grain. They do not form a

surface lm, are porous to water vapor, and penetrate the surface. Because

they do not form a surface lm, they do not blister or peel. Penetrating stains

are alkyd or oil based, and may contain a fungicide or mildewcide as well as

a water repellent. Latex-based stains are also available but do not penetrate

the wood surface as do the oil-based stains.

These stains are not effective when applied over a solid color stain or over

old paint. They are not recommended for use on hardwood but provide an

excellent nish on weathered wood.

Transparent coatings. Conventional spar or marine varnishes produce a

lm-forming nish and are not generally recommended for exterior use on

wood. Shellac or lacquers should never be used outdoors because they are

brittle and very sensitive to water. Exposure to sunlight causes varnish coat-

ings to become brittle and to develop severe cracking and peeling, often in

less than 2 years.

4.8.6 indoor atmospheric Corrosion

Atmospheric corrosion poses a problem indoors as well as outdoors. As

can be expected, there are obvious differences between outdoor and indoor

exposure conditions that lead to a difference between outdoor and indoor

corrosion behaviors.

Under outdoor exposure conditions, the aqueous layer is inuenced by

seasonal and daily changes in humidity and by precipitation (dew, fog, or

snow), whereas indoors the aqueous layer is apt to be governed by relatively

constant humidity conditions. In this situation, for all practical purposes,

there will be an absence of wet-dry cycles, and therefore the effect of indoor

humidity will introduce a time-of-wetness factor.

In general, most gaseous pollutants found outdoors have considerably

lower levels of concentration indoors, with the exception of NH

3

and HCHO.

Pollutants such as HCHO and HCOOH are important indoor corrosion

154 Fundamentals of Corrosion

stimulants. They originate from adhesives, tobacco smoke, combustion of

biomass, and plastics.

Another factor contributing to a decreased indoor corrosion rate is the

decreased levels of indoor atmospheric oxidants, many of which are photo-

chemically produced.

As discussed previously, not only the concentration of pollutants but also

the air velocity determines the dry deposition velocity of corrosion stimu-

lants. Because the air velocity is decreased indoors, signicantly lower dry

deposition velocities will take place.

Based on the differences between the indoor and outdoor factors affecting

atmospheric corrosion rates, it follows that the corrosion rate of many metals

is lower indoors than outdoors. This has been veried by examining the cor-

rosion rates of copper, nickel, cobalt, and iron in eight indoor locations. In all

cases, they exhibited a lower corrosion rate indoors than outdoors.

These factors do not eliminate the possibility of indoor atmospheric cor-

rosion of materials. Designs must take into account the possibility of indoor

atmospheric corrosion.

In an uncontaminated atmosphere at constant temperature, and with the

relative humidity below 100%, corrosion of metals would not be expected.

However, this is never the case because there are always normal temperature

uctuations: as the temperature decreases, the relative humidity increases;

and because of hygroscopic impurities in the atmosphere or in the metal

itself, the relative humidity must be reduced to a much lower value than

100% in order to ensure that no water condenses on the surface. For all met-

als there is a critical relative humidity below which corrosion is negligible.

These critical relative humidities fall between 50 and 70% for steel, copper,

nickel, and zinc.

In design, areas where dust particles can accumulate should be eliminated,

as well as any crevices or pockets. Even in indoor atmospheres, carbon steel

should be protected from corrosion by means of rust preventatives, painting,

galvanizing, or other protective coatings, depending on the conditions of

exposure. The use of low-alloy steel also helps to reduce or eliminate corro-

sion. Atmospheric corrosion is reduced when steel is alloyed in small con-

centrations with copper, potassium, nickel, and chromium.

References

1. Schweitzer, P.A., 1999, Atmospheric Degradation and Corrosion Control, New York:

Marcel Dekker, p. 20.

2. Schweitzer, P.A., 1999, Atmospheric Degradation and Corrosion Control, New York:

Marcel Dekker, p. 17.

Atmospheric Corrosion 155

3. Schweitzer, P.A., 1999, Atmospheric Degradation and Corrosion Control, New York:

Marcel Dekker, p. 22, 23.

4. Schweitzer, P.A., 1999, Atmospheric Degradation and Corrosion Control, New York:

Marcel Dekker, p. 42.

5. Kucera, V. and Mattsen, E., 1989, Atmospheric Corrosion, in Manseld, F., Ed.,

Corrosion Mechanisms, New York: Marcel Dekker, p. 258.

6. Kucera, V. and Mattsen, E., 1989, Atmospheric Corrosion, in Manseld, F., Ed.,

Corrosion Mechanisms, New York: Marcel Dekker, p. 266.

7. Schweitzer, P.A., 1999, Atmospheric Degradation and Corrosion Control, New York:

Marcel Dekker, p. 117.

8. Schweitzer, P.A., 1999, Atmospheric Degradation and Corrosion Control, New York:

Marcel Dekker, p. 119.

9. Schweitzer, P.A., 1999, Atmospheric Degradation and Corrosion Control, New York:

Marcel Dekker, p. 132.

10. Schweitzer, P.A., 1999, Atmospheric Degradation and Corrosion Control, New York:

Marcel Dekker, p. 133.

11. Schweitzer, P.A., 1999, Atmospheric Degradation and Corrosion Control, New York:

Marcel Dekker, p. 137.

12. Schweitzer, P.A., 1999, Atmospheric Degradation and Corrosion Control, New York:

Marcel Dekker, p. 136.

13. Schweitzer, P.A., 1999, Atmospheric Degradation and Corrosion Control, New York:

Marcel Dekker, p. 150.

14. Schweitzer, P.A., 1999, Atmospheric Degradation and Corrosion Control, New York:

Marcel Dekker, p. 145.

15. Schweitzer, P.A., 1999, Atmospheric Degradation and Corrosion Control, New York:

Marcel Dekker, p. 144.

16. Schweitzer, P.A., 1999, Atmospheric Degradation and Corrosion Control, New York:

Marcel Dekker, p. 146.

17. Schweitzer, P.A., 1999, Atmospheric Degradation and Corrosion Control, New York:

Marcel Dekker, p. 147.

18. Schweitzer, P.A., 1999, Atmospheric Degradation and Corrosion Control, New York:

Marcel Dekker, p. 172.

19. Schweitzer, P.A., 1999, Atmospheric Degradation and Corrosion Control, New York:

Marcel Dekker, p. 176.

20. Schweitzer, P.A., 1999, Atmospheric Degradation and Corrosion Control, New York:

Marcel Dekker, p. 179.

21. Schweitzer, P.A., 1999, Atmospheric Degradation and Corrosion Control, New York:

Marcel Dekker, p. 193.

22. Schweitzer, P.A., 1999, Atmospheric Degradation and Corrosion Control, New York:

Marcel Dekker, p. 193.

23. Schweitzer, P.A., 1999, Atmospheric Degradation and Corrosion Control, New York:

Marcel Dekker, p. 198.

24. Schweitzer, P.A., 1999, Atmospheric Degradation and Corrosion Control, New York:

Marcel Dekker, p. 201.

25. Leygraf, Atmospheric Corrosion in P. Marcus, J. Oudar, Eds., Corrosion

Mechanisms in Theory and Practice, New York: Marcel Dekker, p. 423.

157

5

Corrosion of Polymer (Plastic) Materials

As discussed previously, metallic materials undergo a specic corrosion rate

as a result of an electrochemical reaction. Because of this, it is possible to

predict the life of a metal when in contact with a corrodent under a given set

of conditions. This is not the case with polymeric materials. Plastic materi-

als do not experience a specic corrosion rate. They are usually completely

resistant to chemical attack or they deteriorate rapidly. They are attacked

either by chemical reaction or by solvation. Solvation is the penetration of

the plastic by a corrodent, which causes softening, swelling, and ultimate

failure. Corrosion of plastics can be classied in the following ways as to the

attack mechanism:

1. Disintegration or degradation of a physical nature due to absorption,

permeation, solvent action, or other factors

2. Oxidation, where chemical bonds are attacked

3. Hydrolysis, where ester linkages are attacked

4. Radiation

5. Thermal degradation involving depolymerization and possibly

repolymerization

6. Dehydration (rather uncommon)

7. Any combination of the above

Results of such attacks will appear in the form of softening, charring, craz-

ing, delamination, discoloration, dissolving, or swelling.

The corrosion of polymer matrix composites is also affected by two other

factors: the nature of the laminate and, in the case of the thermoset resins,

the cure. Improper or insufcient cure time will adversely affect the cor-

rosion resistance, whereas proper cure time and procedures will generally

improve the corrosion resistance.

All polymers are compounded. The nal product is produced to certain

specic properties for a specic application. When the corrosion resistance of

a polymer is discussed, the data referred to are that of the pure polymer. In

many instances, other ingredients are blended with the polymer to enhance

certain properties, which in many cases reduce the ability of the polymer to

resist attack of some media. Therefore it is essential to know the makeup of

any polymer prior to its use.

158 Fundamentals of Corrosion

5.1 Radiation

Polymeric materials in outdoor applications are exposed to weather

extremes that can be extremely deleterious to the material, the most harm-

ful of which is exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, which can cause

embrittlement, fading, surface cracking, and chalking. Most plastics, after

being exposed to direct sunlight for a period of years, exhibit reduced

impact resistance, lower overall mechanical performance, and a change

in appearance.

The electromagnetic energy from sunlight is normally divided into UV

light, visible light, and infrared energy. Infrared energy consists of wave-

lengths longer than the visible red wavelengths, and starts above 760 nm.

Visible light is dened as radiation between 400 and 760 nm. UV light con-

sists of radiation below 400 nm. The UV portion of the spectrum is further

subdivided into UV-A, UB-B, and UV-C. The effects of the various wave-

length regions are shown below:

Ultraviolet Wavelength Regions

Region

Wavelength

(nm) Characteristics

UV-A 400–315 Causes polymer damage

UV-B 315–280 Includes the shortest wavelengths at the Earth’s surface

Causes severe polymer damage

Absorbed by window glass

UV-C 280–100 Filtered by the Earth’s atmosphere

Found only in outer space

Because UV is easily ltered by air masses, cloud cover, pollution, and other

factors, the amount and spectrum of natural UV exposure is extremely vari-

able. Because the sun is lower in the sky during the winter months, it is

ltered through a greater air mass. This creates two important differences

between summer and winter sunlight: changes in the intensity of the light

and in the spectrum. During the winter months, much of the damaging

shortwavelength UV light is ltered out. For example, the intensity of UV at

320 nm changes about 8 to 1 from summer to winter. In addition, the short-

wavelength solar cut-off shifts from about 295 nm in summer to about 310

nm in winter. As a result, materials sensitive to UV below 320 nm would

degrade only slightly, if at all, during the winter months.

Photochemical degradation is caused by photons of light breaking chemical

bonds. For each type of chemical bond there is a critical threshold wavelength

of light with enough energy to cause a reaction. Light of any wavelength