Ripper J. American Stories: Living American History. Volume 2: From 1865

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

THE U.S. GOVERNMENT

59

4

The U.S. Government

At Home and Abroad

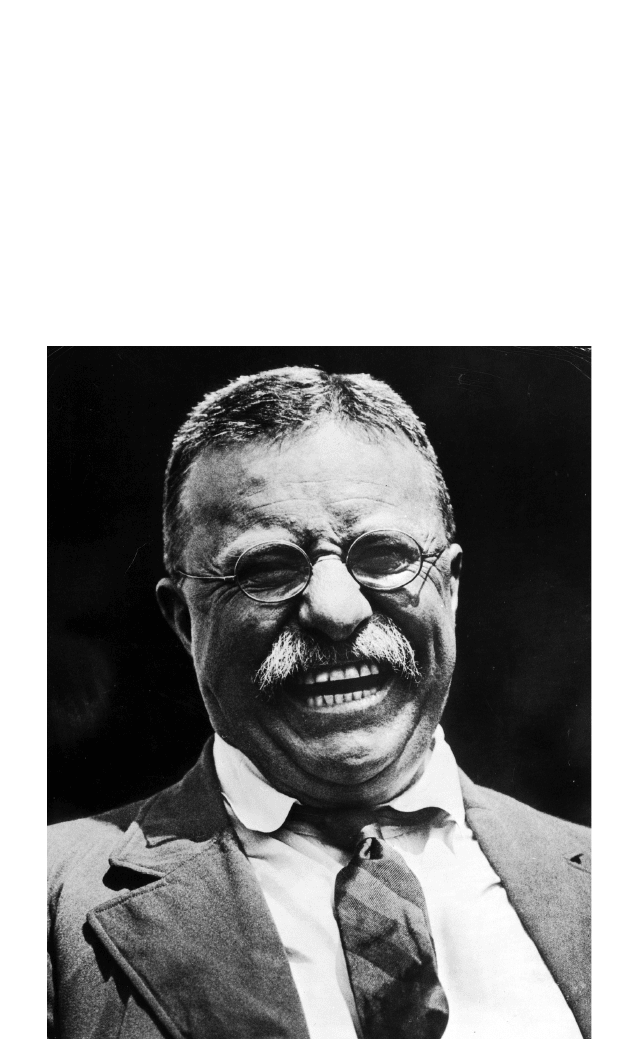

Theodore Roosevelt (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

AMERICAN STORIES

60

The Scene at Home

To what extent should the federal government regulate domestic affairs and

actively, even aggressively, promote U.S. international interests? At the turn

of the twentieth century, Americans faced this question with more urgency

than they had since the Civil War. Violence continued between workers and

their employers’ hired muscle. Effects lingered from the economic panic of

1893. Corporations’ influence and power continued to grow. Packaged foods

remained arguably unsafe. Wholesale clear-cutting of forests, decreasing

runs of fish, and polluted waterways hinted at disaster. Some cities, like San

Francisco, had insufficient water supplies. And worrisome troubles stewed

in Hawaii, Cuba, and the Philippines. Citizens and legislators had to decide

what roles the federal government should take, if any.

Past precedents suggested present solutions. During the Civil War, Presi-

d

ent Abraham Lincoln had sliced into civil liberties because he believed

the cause of union demanded drastic measures. Critics had grumbled when

Lincoln and Congress instituted both an income tax and military draft and

when Lincoln suspended habeas corpus throughout the nation—largely in

response to protests against the draft. Soon after the war ended, however,

habeas corpus was restored. Congress ended the income tax in 1872. And

the army shrank from 1 million men to 26,000 within a decade. As the need

for a mammoth federal government had receded, so too had the scope of the

government’s intervention.

Even so, the number of federal departments, bureaus, agencies, and em-

ployees

had grown steadily since 1789. Each increase came accompanied

by a sensible explanation. For example, the Secret Service got its start in

1865 to counteract counterfeit money. Secret Service agents began their first

presidential protection detail with Grover Cleveland in 1883—eighteen years

too late for Lincoln, and two years too late for President James Garfield, who

was assassinated a few months after his inaugural by a disgruntled federal job

seeker named Charles Guiteau.

Presidential

murder in pursuit of a federal job proved the final nudge in

getting Congress to pass sweeping civil service reform: the Pendleton Act of

1883, which set up the Civil Service Commission, responsible for establishing

hiring guidelines for federal jobs. In a February 1891 Atlantic Monthly article,

Theodore Roosevelt, a member of the commission, wrote, “We desire to make

a man’s honesty and capacity to do the work to which he is assigned the sole

tests of his appointment and retention.” In the 1830s, President Andrew Jackson

had defended the “spoils system,” the practice of handing out plum jobs to

friends and supporters. Although Jackson’s opponents grumbled at the extra

power the spoils system infused into the office of the president, his executive

61

THE U.S. GOVERNMENT

successors continued the practice of handing federal jobs to sycophants. But

the scandals that dogged President Ulysses S. Grant’s time in office, from 1869

to 1877, provided solid evidence that good relations with the president were

no guarantee of a job seeker’s intentions or abilities, no matter how reputable

the president. Grant seems to have been an honest man surrounded by leeches.

His confidant and private secretary, General Orville E. Babcock—though

ultimately found not guilty—was implicated and indicted for what was likely

his central role in defrauding the government of millions of tax dollars, part

of the notorious “Whiskey Ring.” Was it to be men of talent or men of con-

nections

who ran the world’s first successful republic in 2,000 years? If the

federal government was to be a major employer, then its procedures needed

to be orderly and regulated, in much the same way that large corporations

were instituting efficient management and personnel practices.

The size of the federal government alone did not mean that it was exceeding

its constitutional powers. In 1887, however, Congress passed the Interstate

Commerce Act, followed three years later by the Sherman Antitrust Act: two

laws that gave Congress the power to regulate the economy on a case-by-case

basis. This was something radically new. Business was fast becoming the pulse

of the nation, and the common philosophy of the day stressed free-market

economics, the belief that competition between companies would ensure the

“survival of the fittest.” In the early 1800s, when large corporations had not

existed and almost everyone had farmed, federal involvement in the economy

had mostly been limited to imposing tariffs—taxes on imported goods—with

the intention of protecting domestic manufactures by making imported goods

unnaturally pricey. Otherwise, Congress regularly gave away free land or

sold it for a pittance, giving people the one thing they needed—soil to plow.

In the 1820s, the efforts of Speaker of the House Henry Clay to implement

his “American System” of government-sponsored road building had been

met with lamentations about the insidious interference of the government

in private (or at most state) matters. Even funding the Erie Canal by New

York State tax dollars had seemed to many critics a dangerous move. Under

the original model of republican philosophy, citizens had feared the federal

government. The framers of the Constitution had wanted to keep the president

from becoming a tyrant, to keep either house of Congress from growing too

powerful, and to keep the federal government from abusing the prerogatives

of the states. But now, with the passing of the Interstate Commerce and

Sherman Antitrust laws, Congress perceived companies and corporations, es-

sentially

conglomerations of private citizens, as threats to the common good.

The federal government—the old monster hiding under the bed—was slowly

becoming the public defender.

Corporations like John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company and Philip

AMERICAN STORIES

62

Armour’s meatpacking houses in Chicago challenged the autonomous agrarian

order of farmers hoeing their own vegetable patches and scything their own

fields of wheat. And James Pierpont Morgan’s financial holding system gave

him control over railroad networks, steel factories, banks, and coalfields—to

the tune of $22 billion, which was more capital than the federal government

had at the time. Some of these “captains of industry,” or “robber barons,” as

they were also known, welcomed federal oversight. With every federal in-

s

pection stamp applied to a package of Armour sausages, international buyers

could feel confident that American meats were safe to eat. Sometimes busi-

ness

and government entered into willing partnership. There were, however,

more industrialists and financiers opposed to the oversight and interference

of the government. Bulbous-nosed, temperamental J.P. Morgan had bought

Andrew Carnegie’s U.S. Steel because he wanted to integrate steel making

into his shipping interests in order to stabilize the economy. Morgan thought

too much competition bred wild fluctuations into the economy, but Presidents

William McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt, and William Howard Taft—one

after the other—disagreed. These three Republican presidents brought the

Sherman Antitrust Act down upon more than 100 corporations and holding

companies—“trusts”—in order to prevent one company or even one man

(like Morgan) from monopolizing too much money and power. In his 1913

Autobiography, former president Theodore Roosevelt argued that 100 years of

unregulated capitalism had given “perfect freedom for the strong to wrong the

weak.” Saying there had been “in our country a riot of individualistic material-

i

sm,” Roosevelt justified his use of federal power to constrain the Morgans and

R

ockefellers from preying “on the poor and the helpless.”

1

Although President

Taft “busted” more trusts than Roosevelt, it is Theodore Roosevelt who has

continued to be known as the preeminent trust-buster. In fact, five-foot-eight,

barrel-chested Roosevelt was known for just about anything a man could hope

to do, due in great part to his own knack for self-promotion.

Theodor

e Roosevelt, Part 1: Of Silver Spoons and

P

olice Badges

Millions of inherited dollars and an ebullient family spirit—as well as owner-

ship

of an import-export business, a controlling stake in Chemical Bank, and

connections to New York City’s other leading families—freed the Roosevelts

to chase their own fancies. Descended from some of the earliest Dutch settlers

to colonize Manhattan, the Roosevelts grew with the city, building mansions

adjacent to the financial district and raising each generation to prosper and

think. They were as much a family of the mind as they were a family of the

dollar. In 1858, Theodore Roosevelt—the future president—was born to a

63

THE U.S. GOVERNMENT

stalwart father and a story-filled southern mother, Martha Bulloch.

2

Theodore

Roosevelt Sr., born in 1831, chose not to fight in the Civil War—paying

$1,000 for a substitute instead—but he did more for the Union cause than any

single soldier could have accomplished.

Philanthropy

is a pursuit of the wealthy, a sort of voluntary welfare that

appealed to a nation of self-styled rugged individualists. In the emerging

American capitalist arrangement, individuals could choose whether to spend,

save, or give away their own money. Government neither doled out relief nor

forced the wealthy to help the indigent. Rich colonists and their republican

descendants had been expected to dispense alms to the needy, a workable

arrangement in villages and small towns. But the immensity of poverty in

nineteenth-century cities overwhelmed the ability of individuals to dispense

food and coins. A few hundred leading families did not have personal networks

in place to handle the needs of tens of thousands of urban poor. And besides,

the precedent for large-scale, philanthropic poor-relief simply did not exist.

How to alleviate widespread poverty was a new problem made worse by the

devastation of the Civil War, which not only killed wage-earning fathers and

sons, but at the very least left mothers and young children at home to fend for

themselves until their battle-scarred fathers and husbands returned.

T

heodore Roosevelt Sr. decided to do something on a massive scale to help

soldiers’ struggling families, and he thought the federal government ought to

be at the center of his efforts. This wealthy man with a deserved reputation

for philanthropic work wanted to enlist Lincoln’s Union government in the

cause of the common good. Seeing government as an aid, not as a hindrance

or lurking foe, Roosevelt went with two friends to visit President Lincoln in

the capital. The president supported their idea for an allotment system, a way

of sending home some of a soldier’s pay. With Lincoln’s blessing, Roosevelt

convinced Congress to enact the plan and soon began convincing New York

State soldiers, over whom he had been made allotment commissioner. For two

years he toured Army camps, signing men up for the program and overseeing

the distribution of funds, which totaled in the millions.

P

rior to the war and afterward, Theodore Sr. dedicated himself in other ways

to alleviating the hazards of urban poverty. In part, he funded an orphanage,

the Newsboys’ Lodging House, to which he went every Sunday afternoon,

often bringing young Theodore along. The future president would watch his

father dispense good advice and encouragement, pepping the youngsters to

study and work hard. Over the years, thousands of the orphans were placed

in midwestern farm families, away from the grime of New York’s underside.

In 1913, Theodore Roosevelt published his autobiography and with great

admiration remembered his father as “the best man I ever knew. . . . He was

interested in every social reform movement, and he did an immense amount

AMERICAN STORIES

64

of practical charitable work himself.” The elder Roosevelt died in 1878 at

the too-young age of forty-six, when his son was halfway through Harvard.

The father had lived long enough, however, to provide a model for the rest of

Theodore’s life. The future president recalled how his father’s “heart filled

with gentleness for those who needed help or protection, and with the pos-

sibility of much wrath against a bully or an oppressor

.”

3

All was not philanthropy and tender care giving in young Roosevelt’s

childhood. There was also fascination with nature. He remembered, “rais-

ing

a family of very young gray squirrels [and] fruitlessly endeavoring to

tame an excessively unamiable woodchuck.”

4

The family hiked the Alps and

took a float down the Nile, where he blasted away at ibises with a shotgun.

Theodore and his three siblings studied with private tutors. Some nights,

when bronchial asthma filled his frail lungs with swollen tissue and fluid, his

father would wander the mansion, carrying the “gasping” boy from room to

room. Occasionally they would load into a carriage and trot through the night

streets of New York, letting the motion and cool air calm young Theodore’s

nerves and soothe his breathing. He remembered his mother, Martha, with

equal love. She was from the South and remained “entirely ‘unreconstructed’

to the day of her death,” an attitude that in a less loving family might have

caused problems. In the Roosevelt household, having a Union-leaning father

and Confederate-leaning mother led to nothing more than mischief and play.

The ex-president recalled the dawning in his child’s mind of “a partial but alert

understanding of the fact that the family were not one in their views about”

the war. To pay his mother back for a dose of daytime “maternal discipline,”

he tried “praying with loud fervor for the success of the Union arms” during

the evening prayer. Luckily for the mischievous boy, his mother was “blessed

with a strong sense of humor, and she was too much amused to punish me.”

5

Unlike the orphaned boys he visited on Sunday afternoons with his father,

bereft as they were of family, Theodore Roosevelt had loving parents and

playful siblings to influence him and instill a belief that people could be good

when circumstances permitted.

A

fter graduating from Harvard in 1880, Theodore Roosevelt scanned

his prospects—which were many—and chose two marriages: one to Alice

Lee; the second to the public. He would break with genteel tradition and

become a politician. Educated sons of privilege scorned politics in the late

1800s, considering it the domain of ruffians, attention seekers, and men

of ambition, a quality that was not necessary for those already at the top

of the national pyramid. The world already stretched out beneath them.

Roosevelt’s well-heeled friends scoffed at his political intentions, warning

him away from the “saloon-keepers, horse-car conductors, and the like”

whom he would have to deal with as equals. Roosevelt, however, had had

65

THE U.S. GOVERNMENT

quite enough of billiard rooms and talk that went nowhere. He had the

example of his father before him, a first-rate education, and an internal

drive to better himself and the nation at all turns. Politics was the place to

accomplish his vision. As he told his blue-blood friends, “I intended to be

one of the governing class.”

6

One year out of college, Roosevelt got elected to the New York State legis-

lature, where he remained for three terms, distinguishing himself as a cautious

reformer who listened attentively and spoke forcefully. He devoted special

zeal to civil service reform, helping enact the first statewide civil service laws

in 1883, just before passage of the Pendleton Act nationally. This made him,

in effect, the champion of competence and honesty, setting him at odds with

the lords of tradition, represented by city political machines—notably New

York’s own Tammany Hall, the heart and soul of Democratic politics for more

than 100 years, well into the 1900s. Although Tammany’s most notorious

leader—graft-swollen William Marcy Tweed, known as “Boss” Tweed—had

been jailed in the 1870s for skimming upward of $200 million from city cof-

fers,

the Tammany political organization maintained tight control over city

jobs and contracts, exchanging votes for employment. The political machine

system benefited fresh immigrants who needed work, protection, and access to

basic services, but the same system also stymied reform and made graft easy.

Roosevelt’s time in state office endeared him to President Benjamin Harrison,

who appointed Theodore as a federal Civil Service Commissioner in 1889. The

step from state to federal government had been natural and easy for Roosevelt,

though contemporary events in his own life proved more tumultuous.

O

n February 14, 1884, Theodore Roosevelt’s mother and wife both died. The

twin deaths left him hollow, and he turned to the same part of the country so

many men before him had used as a crucible for recasting a shattered life: the

West, in his case North Dakota. Landscapes of trees, mountains, and streams

had always tugged at Roosevelt’s spirit. He found more to bind the mind in

wilderness than in anything else other than politics. (Later in life he found a way

to bring his love of nature and his gift for politics together.) The Roosevelts had

spent summers on Long Island, when it still harbored tangled places and quiet

dunes. The best parts of his two trips to Europe had been its natural vistas and

ancient ruins, the parts of civilization at least partially returned to the earth. At

the age of thirteen, Roosevelt had learned the skills of taxidermy, which blended

well with his bird hunting and general interest in “natural history,” the catch-all

phrase for human history and earth sciences tumbled together. What better place,

then, than North Dakota, still a territory and still untamed enough for ranching,

grizzly hunting, and bandit rassling, all of which Roosevelt fit into his two years

on the range—along with solitary trips through the moonscape of the Badlands,

haunted as it was with dinosaur bones and other relics of time.

AMERICAN STORIES

66

In 1886, Roosevelt returned to the East—though the West was never far

from his mind. He fully resumed a settled life by marrying a childhood

friend, Edith Carow, with whom he had five children to accompany the one

from his previous marriage (named after her mother, Alice, who had died

from childbirth complications). He also tried his luck at a mayoral election,

which he lost. Along with his six years as a civil service commissioner

(preceded by working on Benjamin Harrison’s successful presidential bid),

Roosevelt spent most of the next decade in personal ways, writing an epic

history of the West in four volumes and raising his wild brood. But 1895

found Roosevelt back in a reformer’s chair, serving as police commissioner

for New York, where he had to fight against nearly as many problems inside

the department as its officers faced daily on the streets. Training standards

were either lax or nonexistent. For example, patrolmen received few to no

lessons in pistol use, though they were given revolvers. Protection rackets

took up as much time as protection of innocent citizens. It was common

police practice to extort weekly fees from brothels in exchange for letting

prostitutes continue their business. And night patrol was seen as a good

time to take a nap. For two years, Roosevelt cleaned up shop, informing

the officers that he would judge them according to the quality of their

patrolmen’s police work. In typical Roosevelt fashion, he did the judging

personally by wandering the streets at night, keeping tabs on his own in-

c

reasingly alert force. This was all a matter of “merit” and responsibility

as far as Roosevelt was concerned, another facet of his intention to fill civil

service jobs with men who performed well. After his two years of institut-

i

ng effective reforms and training procedures, the nation again called out

to Theodore Roosevelt, and he excused himself from police oversight to

take a larger cop’s job, assistant secretary of the navy, in 1897. The tim-

i

ng, for a man of Roosevelt’s tastes, temperament, and toughness, could

not have been better.

An International Interlude: Cuba, Hawaii, and the

Pr

elude to War

After Theodore Roosevelt retired from the presidency in 1909, he grabbed a

big-game rifle and some buddies, notified enough reporters to keep the name

“Roosevelt” in the newspapers, and steamed for Africa. His son Kermit was

the expedition’s photographer, mirroring Roosevelt’s own family shooting

trip down the Nile some thirty years earlier (when a minimum of 100 birds

had been shot, destined for stuffing and storage in young Roosevelt’s grow-

ing

home taxidermy collection). In 1909, besides wanting to have a “bully”

time in Africa, ex-President Roosevelt was off to prove his manliness by

67

THE U.S. GOVERNMENT

blasting anything that moved—other than people. Roosevelt and company

killed more than 250 animals, including eight elephants, seven giraffes, seven

hippopotamuses, five pelicans, and nine lions. The American public, in turn,

lionized Roosevelt, cheering at news of his ongoing “strenuous life.” In a 1910

dispatch from Khartoum in the Sudan, the ex-president informed readers that

he had gone “where the wanderer sees the awful glory of sunrise and sunset

in the wide waste spaces of the earth, unworn of man, and changed only by

the slow change of the ages through time everlasting.”

7

Roosevelt’s yearlong tour of Africa did more than impress his nation

of admirers. The tour reinforced a handful of notions: animals and nature

were present for humans to “use” as they saw fit; Africa had produced no

real civilizations of its own, leaving the continent “unworn of man”; and the

United States should continue to share its bold democracy with the world.

During the 1800s, Europeans colonized most of Africa, and in the century’s

closing decade, the United States established Hawaii as a territory and the

Philippines, Cuba, and Puerto Rico as colonial protectorates. These forays

into Africa, the Caribbean, and the Pacific islands were generally understood

to be part of the “white man’s burden,” a responsibility to do two things: to

bring the modern wonders of white civilization to dark peoples and to make

money in the process. Where once it had been the responsibility of mission-

ary

societies to spread American culture on a global scale, now the federal

government—through its navy and army—was asserting American global

aspirations. Theodore Roosevelt was delighted to display the United States

flexing its muscles, and he was not shy to say so. In 1895, he spelled out his

image of the American colossus. “We should,” he said, “build a first-class

fighting navy. . . . We should annex Hawaii immediately. It was a crime against

the United States, it was a crime against white civilization, not to annex it

two years and a half ago [when Queen Liliuokalani was deposed by white

landowners]. . . . We should build the Isthmian Canal, and it should be built

either by the United States Government or under its protection.” In his own

gymnastic prose, Roosevelt proclaimed both peace and war as just policies:

“Honorable peace is always desirable, but under no circumstances should

we permit ourselves to be defrauded of our just rights by any fear of war.”

This was an early version of Roosevelt’s dictum, “Speak softly and carry a

big stick.”

8

In 1887, Theodore Roosevelt had met Alfred Thayer Mahan at the United

States Naval War College. Three years later, Mahan published The Influence

of Sea Power Upon History, a book that Roosevelt took seriously. Mahan

theorized that during the colonial period (stretching back to Rome), navies

had determined which empire would prevail: whoever controlled the seas

could control commerce; and whoever’s commerce could be sustained could