Richard L. Daft - Management. 9th ed., 2010

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

PART 5 LEADING450

▪ Change outcomes. A person may change his or her outcomes. An underpaid per-

son may request a salary increase or a bigger of ce. A union may try to improve

wages and working conditions to be consistent with a comparable union whose

members make more money.

▪ Change perceptions. Research suggests that people may change perceptions of

equity if they are unable to change inputs or outcomes. They may arti cially

increase the status attached to their jobs or distort others’ perceived rewards to

bring equity into balance.

▪ Leave the job. People who feel inequitably treated may decide to leave their jobs

rather than suffer the inequity of being under- or overpaid. In their new jobs, they

expect to nd a more favorable balance of rewards.

The implication of equity theory for managers is that employees indeed evaluate the

perceived equity of their rewards compared to others’. Inequitable pay puts pressure

on employees that is sometimes almost too great to bear. They attempt to change their

work habits, try to change the system, or leave the job.

27

Consider Deb Allen, who went

into the of ce on a weekend to catch up on work and found a document accidentally

left on the copy machine. When she saw that some new hires were earning $200,000

more than their counterparts with more experience, and that “a noted screw-up” was

making more than highly competent people, Allen began questioning why she was

working on weekends for less pay than many others were receiving. Allen became so

demoralized by the inequity that she quit her job three months later.

28

As a new manager, be alert to feelings of inequity among your team members. Don’t

play favorites, such as regularly praising some while overlooking others making similar

contributions. Keep equity in mind when you make decisions about compensation and

other rewards.

Expectancy Theory

Expectancy theory suggests that motivation depends on individuals’

expectations about their ability to perform tasks and receive desired

rewards. Expectancy theory is associated with the work of Victor Vroom,

although a number of scholars have made contributions in this area.

29

Expectancy theory is concerned not with identifying types of needs but

with the thinking process that individuals use to achieve rewards. Con-

sider Amy Huang, a university student with a strong desire for a B in

her accounting course. Amy has a C+ average and one more exam to

take. Amy’s motivation to study for that last exam will be in uenced by:

(1) the expectation that hard study will lead to an A on the exam and

(2) the expectation that an A on the exam will result in a B for the course.

If Amy believes she cannot get an A on the exam or that receiving an A

will not lead to a B for the course, she will not be motivated to study

exceptionally hard.

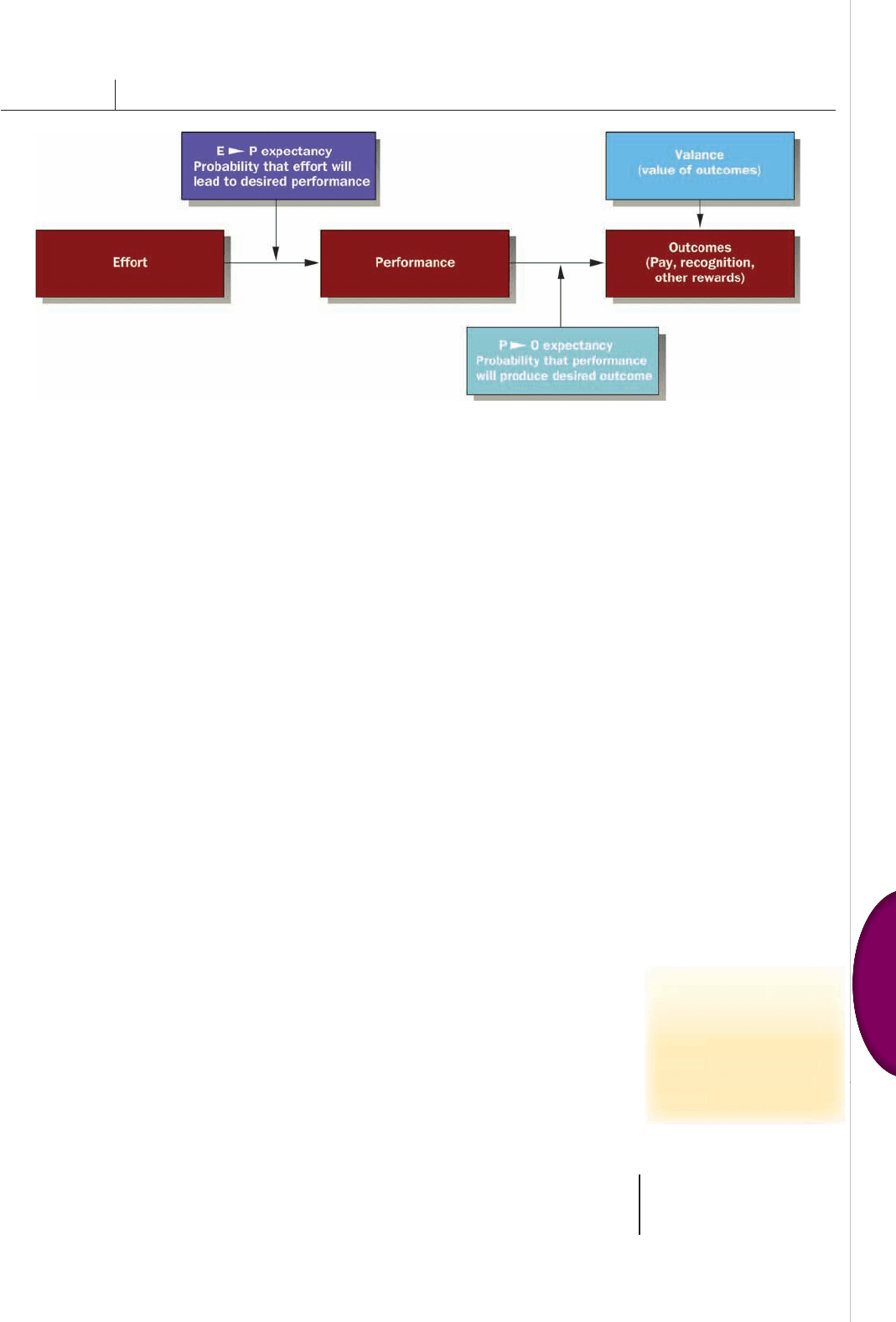

Expectancy theory is based on the relationship among the individ-

ual’s effort, the individual’s performance, and the desirability of outcomes

associated with high performance. These elements and the relationships

among them are illustrated in Exhibit 15.5. The keys to expectancy the-

ory are the expectancies for the relationships among effort, performance,

and the value of the outcomes to the individual.

E ➞ P expectancy involves determining whether putting effort into

a task will lead to high performance. For this expectancy to be high,

the individual must have the ability, previous experience, and neces-

sary equipment, tools, and opportunity to perform. Let’s consider a

simple sales example. If Carlos, a salesperson at the Diamond Gift Shop,

believes that increased selling effort will lead to higher personal sales,

TakeaMoment

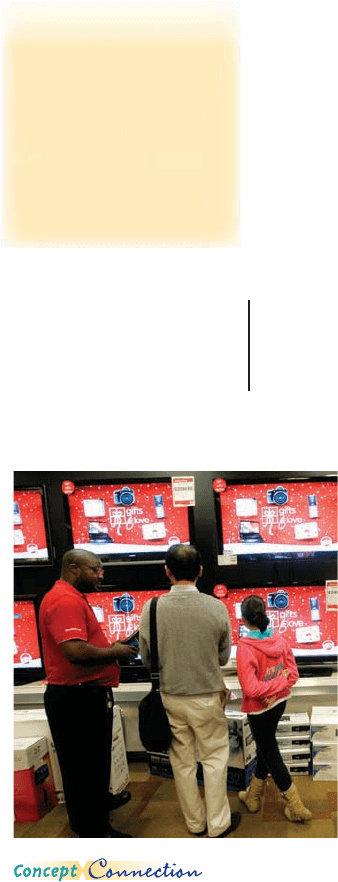

Circuit City man-

agers are using expectancy theory principles to

help meet employees’ needs while attaining or-

ganizational goals. By creating an incentive pro-

gram that is a commission-based plan designed

to provide the highest compensation to sales

counselors who are committed to serving every

customer, Circuit City achieves its volume and

profi tability objectives. The incentive program

is also used in other areas such as distribution,

where employees are recognized for accomplish-

ment in safety, productivity, and attendance.

© AP PHOTO/JEFF CHIU

e

e

e

e

e

exp

ectancy theor

y

A

A

p

p

roc

es

ss

ss

s

s

s

s

t

t

t

h

h

t

t

h

h

eory

th

th

t

a

t

proposes

th

th

a

t

t

m

ti

o

ti

-

-

-

v

v

v

v

v

va

a

tion de

p

ends on individuals’

e

e

e

e

ex

x

pectations about their abilit

y

y

t

t

t

o

o

perform tasks and receive

d

d

d

d

d

es

ir

e

d

r

e

w

a

r

ds

.

E

E

E

E

E

➞

P expectanc

y

E

x

p

ec-

t

t

t

a

a

a

nc

y

that puttin

g

effort into

a

a

a

a

a

g

a

iven task will lead to hi

g

h

p

p

p

p

pe

pe

per

er

p

formance

.

CHAPTER 15 MOTIVATING EMPLOYEES 451

5

Leading

we can say that he has a high E ➞ P expectancy. However, if Carlos believes he has

neither the ability nor the opportunity to achieve high performance, the expectancy

will be low, and so will be his motivation.

P ➞ O expectancy involves determining whether successful performance will

lead to the desired outcome or reward. If the P ➞ O expectancy is high, the individual

will be more highly motivated. If the expectancy is that high performance will not

produce the desired outcome, motivation will be lower. If Carlos believes that higher

personal sales will lead to a pay increase, we can say that he has a high P ➞ O expec-

tancy. He might be aware that raises are coming up for consideration and talk with

his supervisor or other employees to see if increased sales will help him earn a better

raise. If not, he will be less motivated to work hard.

Valence is the value of outcomes, or attraction to outcomes, for the individual.

If the outcomes that are available from high effort and good performance are not

valued by employees, motivation will be low. Likewise, if outcomes have a high

value, motivation will be higher. If Carlos places a high value on the pay raise,

valence is high and he will have a high motivational force. On the other hand, if

the money has low valence for Carlos, the overall motivational force will be low.

For an employee to be highly motivated, all three factors in the expectancy model

must be high.

30

Expectancy theory attempts not to de ne speci c types of needs or rewards

but only to establish that they exist and may be different for every individual.

One employee might want to be promoted to a position of increased responsi-

bility, and another might have high valence for good relationships with peers.

Consequently, the rst person will be motivated to work hard for a promotion

and the second for the opportunity of a team position that will keep him or her

associated with a group. Recent studies substantiate the idea that rewards need

to be individualized to be motivating. A recent nding from the U.S. Department

of Labor shows that the number 1 reason people leave their jobs is because they

“don’t feel appreciated.” Yet Gallup’s analysis of 10,000 workgroups in 30 indus-

tries found that making people feel appreciated depends on nding the right kind

of reward for each individual. Some people prefer tangible rewards or gifts, while

others place high value on words of recognition. In addition, some want public

recognition while others prefer to be quietly praised by someone they admire and

respect.

31

As a new manager, how would you manage expectations and use rewards to motivate

subordinates to perform well? Complete the New Manager Self-Test on page 452 to

learn more about your approach to motivating others.

TakeaMoment

EXHIBIT 15.5 Major Elements of Expectancy Theory

P

P

P

P

P

P

➞

O expectanc

y

E

xpect

anc

c

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

t

t

t

h

ha

h

ha

ts

t

s

ucc

ucc

ess

ess

ful

ful

pe

pe

rfo

rfo

rma

rma

nce

nce

of

of

a

a

a

a

t

a

t

a

ask

ask

wi

wi

ll

ll

lea

lea

dt

d

t

ot

o

t

he

he

des

des

ire

ire

d

d

o

o

o

o

ut

o

o

o

ut

com

com

e

e.

v

v

v

v

va

l

e

n

ce

T

he value or attrac

-

t

t

t

i

i

i

on an individual has for an

o

o

o

o

ou

ou

ut

o

co

m

e.

PART 5 LEADING452

Your Approach to

Motivating Others

Think about situations in which you were in a

student group or organization. Think about your

informal approach as a leader and answer the

questions below. Indicate whether each item

below is Mostly False or Mostly True for you.

1. I ask the other person what rewards they value

for high performance.

2. I only reward people if their performance is up

to standard.

3. I fi nd out if the person has the ability to do

what needs to be done.

4. I use a variety of rewards (treats, recognition)

to reinforce exceptional performance.

5. I explain exactly what needs to be done for the

person I’m trying to motivate.

6. I generously and publicly praise people who

perform well.

7. Before giving somebody a reward, I fi nd out

what would appeal to that person.

8. I promptly commend others when they do a

better-than-average job.

SCORING AND INTERPRETATION: The ques-

t

ions above represent two related aspects of

motivation theory. For the aspect of expectancy

theory, sum the points for Mostly True to the odd-

numbered questions. For the aspect of reinforce-

ment theory, sum the points for Mostly True for

the even-numbered questions. The scores for my

approach to motivation are:

My use of expectancy theory _____

My use of reinforcement theory _____

These two scores represent how you apply the

motivational concepts of expectancy and rein-

forcement in your role as an informal leader. Three

or more points on expectancy theory means you

motivate people by managing expectations. You

understand how a person’s effort leads to perfor-

mance and make sure that high performance leads

to valued rewards. Three or more points for rein-

forcement theory means that you attempt to modify

people’s behavior in a positive direction with

frequent and prompt positive reinforcement. New

managers often learn to use reinforcements fi rst,

and as they gain more experience are able to apply

expectancy theory.

SOURCES: These questions are based on D. Whetten and K.

Cameron, Developing Management Skills, 5th ed. (Upper Saddle

River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 2002), pp. 302–303; and P. M.

Podsakoff, S. B. Mackenzie, R. H. Moorman, and R. Fetter,

“Transformational Leader Behaviors and Their Effects on

Followers’ Trust in Leader, Satisfaction, and Organizational

Citizenship Behaviors,” Leadership Quarterly 1, no. 2 (1990):

107–142.

New ManagerSelf-Test

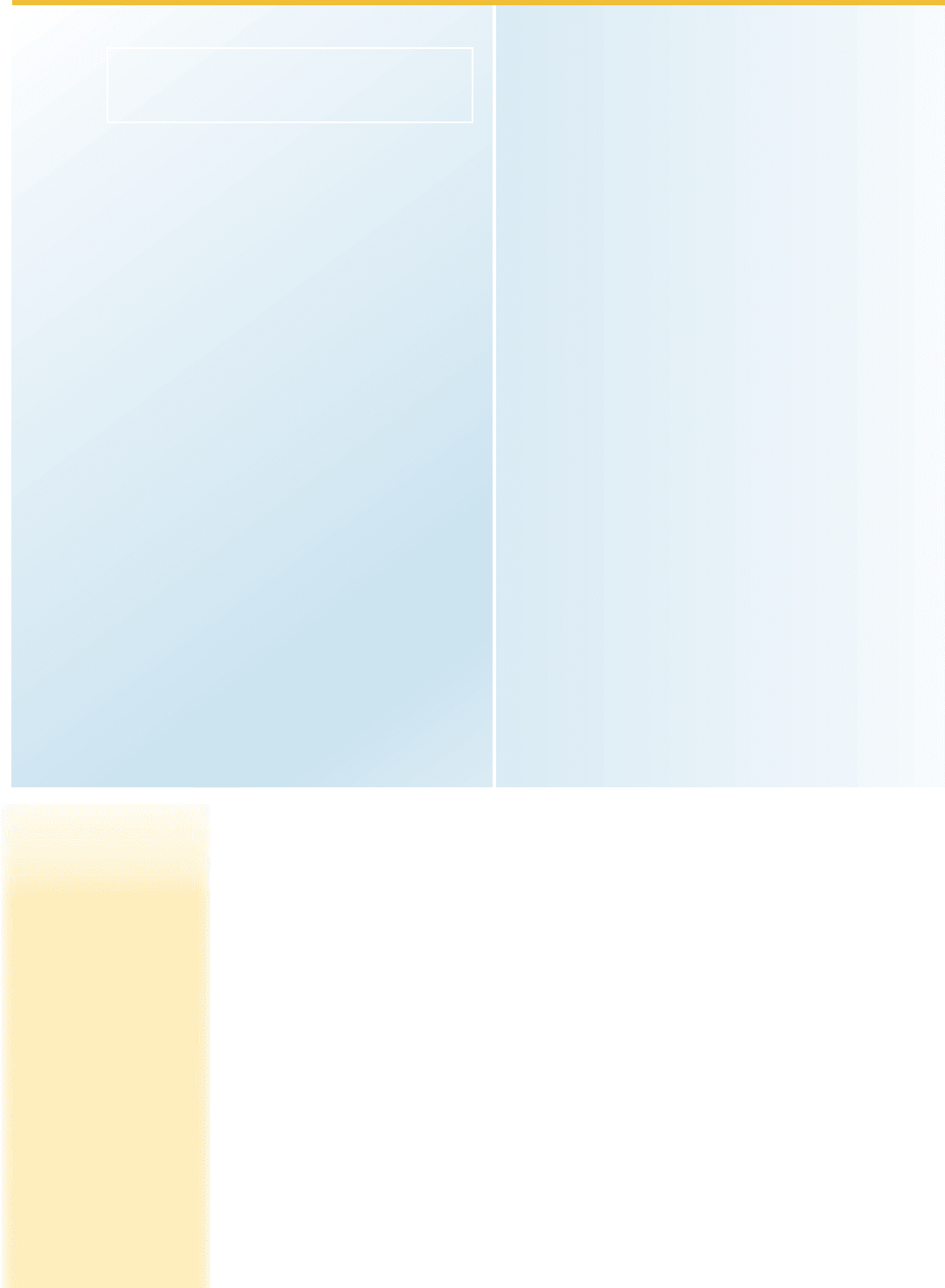

REINFORCEMENT PERSPECTIVE ON MOTIVATION

The reinforcement approach to employee motivation sidesteps the issues of employee

needs and thinking processes described in the content and process theories.

Reinforcement theory simply looks at the relationship between behavior and its

consequences. It focuses on changing or modifying employees’ on-the-job behavior

through the appropriate use of immediate rewards and punishments.

Behavior modi cation is the name given to the set of techniques by which rein-

forcement theory is used to modify human behavior.

32

The basic assumption under-

lying behavior modi cation is the law of effect, which states that behavior that is

positively reinforced tends to be repeated, and behavior that is not reinforced tends

not to be repeated. Reinforcement is de ned as anything that causes a certain behav-

ior to be repeated or inhibited. The four reinforcement tools are positive reinforcement,

avoidance learning, punishment, and extinction, as summarized in Exhibit 15.6.

▪ Positive reinforcement is the administration of a pleasant and rewarding con-

sequence following a desired behavior, such as praise for an employee who

r

r

r

r

re

rei

nforcement theory

A

m

m

m

m

m

otivation theor

y

based on th

e

e

r

r

r

re

e

l

r

r

ationship between a

g

iven

b

b

b

b

b

eh

b

b

avior and its conse

q

u

q

ences

.

.

b

b

b

b

be

h

a

vi

o

r m

od

ifi

cat

i

o

n The

s

s

s

s

se

e

t of techniques by which

r

r

r

r

re

e

inforcement theor

y

is used t

o

o

m

m

m

m

m

m

odif

y

human behavior

.

l

l

l

l

l

aw of effec

t

T

h

e assum

p

tio

n

n

t

t

th

h

h

h

at positively reinforced behavi

o

or

r

r

r

t

t

t

e

e

e

nds to be re

p

eated, and unre

-

i

i

in

n

n

n

forced or ne

g

ativel

y

reinforce

d

d

d

d

d

b

b

b

b

b

e

h

a

vi

o

r

te

n

ds

to

be

inhi

b

i

ted

.

r

r

r

r

r

einforcement Anyt

h

ing t

h

a

t

t

c

c

c

c

ca

a

uses a given behavior to be

r

r

r

r

re

ep

eated or inhibited.

p

p

p

p

p

ositive rein

f

orcemen

t

Th

e

a

a

a

a

ad

d

ministration o

f

a p

l

easant

a

a

a

a

an

nd

rewar

d

ing consequence

f

f

f

fo

o

o

llowing a desired behavior

.

CHAPTER 15 MOTIVATING EMPLOYEES 453

5

Leading

arrives on time or does a little extra

work. Research shows that positive

reinforcement does help to improve

performance. Moreover, non nancial

reinforcements such as positive feed-

back, social recognition, and attention

are just as effective as nancial incen-

tives.

33

One study of employees at fast-

food drive-thru windows, for example,

found that performance feedback and

supervisor recognition had a signi -

cant effect on increasing the incidence

of “up-selling,” or asking customers

to increase their order.

34

Indeed, many

people value factors other than money.

Nelson Motivation Inc. conducted a

survey of 750 employees across vari-

ous industries to assess the value

they placed on various rewards. Cash

and other monetary awards came in

dead last. The most valued rewards

involved praise and manager support

and involvement.

35

▪ Avoidance learning is the removal of

an unpleasant consequence following

a desired behavior. Avoidance learning

is sometimes called negative reinforcement. Employees learn to do the right thing

by avoiding unpleasant situations. Avoidance learning occurs when a supervisor

stops criticizing or reprimanding an employee once the incorrect behavior has

stopped.

▪ Punishment is the imposition of unpleasant outcomes on an employee. Punish-

ment typically occurs following undesirable behavior. For example, a supervisor

may berate an employee for performing a task incorrectly. The supervisor expects

that the negative outcome will serve as a punishment and reduce the likelihood

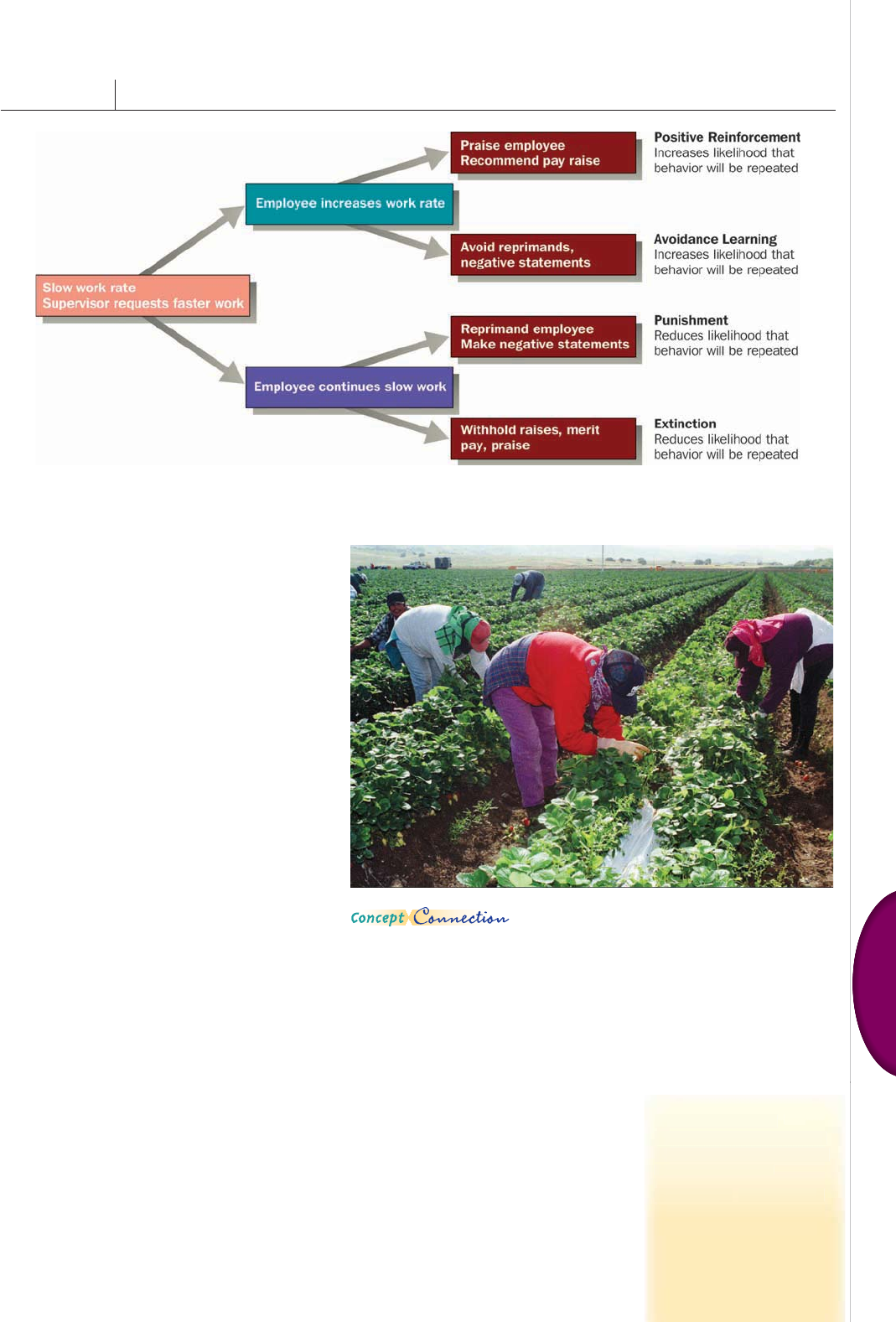

© CLAY PETERSON/THE CALIFORNIAN/ASSOCIATED PRESS

Farm managers apply positive reinforcement by basing

a fruit or vegetable picker’s pay on the amount he or she harvests. A variation on this

individual piece-rate system is a relative incentive plan that bases each worker’s pay on

the ratio of the individual’s productivity to average productivity among all co-workers.

A study of Eastern and Central European pickers in the United Kingdom found that

workers’ productivity declined under the relative plan. Researchers theorized that fast

workers didn’t want to hurt their slower colleagues, so they reduced their efforts. The

study authors suggested a team-based scheme—where everyone’s pay increased if the

team did well—would be more effective.

EXHIBIT 15.6 Changing Behavior with Reinforcement

SOURCE: Based on Richard L. Daft and Richard M. Steers, Organizations: A Micro/Macro Approach (Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman, 1986), p. 109.

a

a

a

a

a

avo

i

d

ance

l

earning

T

h

e

r

r

r

r

re

e

mova

l

o

f

an unp

l

easant con-

s

s

s

se

e

quence w

h

en an un

d

esira

bl

e

e

b

b

b

b

h

b

e

h

b

avior is correc

d

te

d

.

p

p

p

p

p

unishmen

t

h

T

h

e imposition

o

o

o

f

o

f

o

o

an un

p

p

l

l

easant outcome

f

f

o

l

l-

l

l

lo

o

o

o

win

g

un

d

esira

bl

e

b

e

h

avior.

PART 5 LEADING454

of the behavior recurring. The use of punishment in organizations is controver-

sial and often criticized because it fails to indicate the correct behavior. How-

ever, almost all managers report that they nd it necessary to occasionally impose

forms of punishment ranging from verbal reprimands to employee suspensions

or rings.

36

▪ Extinction is the withdrawal of a positive reward. Whereas with punishment,

the supervisor imposes an unpleasant outcome such as a reprimand, extinction

involves withholding pay raises, bonuses, praise, or other positive outcomes. The

idea is that behavior that is not positively reinforced will be less likely to occur

in the future. A good example of the use of extinction comes from Cheektowaga

(New York) Central Middle School, where students with poor grades or bad atti-

tudes are excluded from extracurricular activities such as athletic contests, dances,

crafts, or ice-cream socials.

37

Reward and punishment motivational practices dominate organizations. Accord-

ing to the Society for Human Resource Management, 84 percent of all companies

in the United States offer some type of monetary or nonmonetary reward system,

and 69 percent offer incentive pay, such as bonuses, based on an employee’s perfor-

mance.

38

However, in other studies, more than 80 percent of employers with incen-

tive programs have reported that their programs are only somewhat successful or not

working at all.

39

Despite the testimonies of organizations that enjoy successful incen-

tive programs, criticism of these “carrot-and-stick” methods is growing, as discussed

in the Manager’s Shoptalk.

As a new manager, remember that reward and punishment practices are limited

motivational tools because they focus only on extrinsic rewards and lower-level

needs. Using intrinsic rewards to meet higher level needs is important too.

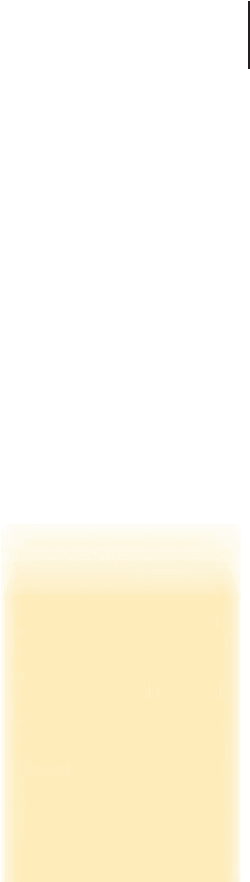

JOB DESIGN FOR MOTIVATION

A job in an organization is a unit of work that a single employee is responsible for per-

forming. A job could include writing tickets for parking violators in New York City,

performing MRIs at Salt Lake Regional Medical Center, reading meters for Paci c

Gas and Electric, or doing long-range planning for the WB Television Network. Jobs

are an important consideration for motivation because performing their components

may provide rewards that meet employees’ needs. Managers need to know what

aspects of a job provide motivation as well as how to compensate for routine tasks that

have little inherent satisfaction. Job design is the application of motivational theories

to the structure of work for improving productivity and satisfaction. Approaches to

job design are generally classi ed as job simpli cation, job rotation, job enlargement,

and job enrichment.

Job Simplifi cation

Job simpli cation pursues task ef ciency by reducing the number of tasks one person

must do. Job simpli cation is based on principles drawn from scienti c management

and industrial engineering. Tasks are designed to be simple, repetitive, and standard-

ized. As complexity is stripped from a job, the worker has more time to concentrate

on doing more of the same routine task. Workers with low skill levels can perform

the job, and the organization achieves a high level of ef ciency. Indeed, workers are

interchangeable because they need little training or skill and exercise little judgment.

As a motivational technique, however, job simpli cation has failed. People dislike

routine and boring jobs and react in a number of negative ways, including sabotage,

TakeaMoment

e

e

e

e

e

ext

i

n

ctio

n The withdrawal

of

of

f

a

a

a

a

p

a

a

p

ositive reward.

j

j

j

j

j

j

o

b

d

esi

g

n

Th

Th

e ap

li

p

li

cat

i

i

on

o

o

o

o

of

f

motivationa

l

t

h

eories to t

h

e

s

s

s

s

st

t

ructure o

f

wor

k

f

or improvin

g

g

g

g

p

p

p

p

p

roductivity and satisfaction

.

j

j

j

j

j

j

o

b

simp

l

i

fi

cation A

j

o

b

d

e-

s

s

s

s

si

i

gn w

h

ose purpose is to impro

v

ve

e

e

e

t

t

t

a

a

a

s

k

e

ffi

ciency

b

y re

d

ucing t

h

e

n

n

n

n

n

um

b

er o

f

tas

k

s a sing

l

e perso

n

n

n

n

m

m

m

m

m

m

ust do.

CHAPTER 15 MOTIVATING EMPLOYEES 455

5

Leading

Everybody thought Rob Rodin was crazy when he

decided to wipe out all individual incentives for his

sales force at Marshall Industries, a large distributor of

electronic components based in El Monte, California.

He did away with all bonuses, commissions, vaca-

tions, and other awards and rewards. All salespeople

would receive a base salary plus the opportunity for

pro t sharing, which would be the same percent of

salary for everyone, based on the entire company’s

performance. Six years later, Rodin says productiv-

ity per person has tripled at the company, but still he

gets questions and criticism about his decision.

Rodin is standing right in the middle of a big

controversy in modern management. Do nan-

cial and other rewards really motivate the kind of

behavior organizations want and need? A growing

number of critics say no, arguing that carrot-and-

stick approaches are a holdover from the Industrial

Age and are inappropriate and ineffective in today’s

economy. Today’s workplace demands innovation

and creativity from everyone—behaviors that rarely

are inspired by money or other nancial incentives.

Reasons for criticism of carrot-and-stick approaches

include the following:

1. Extrinsic rewards diminish intrinsic rewards.

When people are motivated to seek an extrinsic

reward, whether it is a bonus, an award, or the

approval of a supervisor, generally they focus

on the reward rather than on the work they

do to achieve it. Thus, the intrinsic satisfaction

people receive from performing their jobs actu-

ally declines. When people lack intrinsic rewards

in their work, their performance stays just ade-

quate to achieve the reward offered. In the worst

case, employees may cover up mistakes or cheat

to achieve the reward. One study found that

teachers who were rewarded for increasing test

scores frequently used various forms of cheat-

ing, for example.

2. Extrinsic rewards are temporary. Offering out-

side incentives may ensure short-term success,

but not long-term high performance. When

employees are focused only on the reward, they

lose interest in their work. Without personal

interest, the potential for exploration, creativity,

and innovation disappears. Although the cur-

rent deadline or goal may be met, better ways

of working and serving customers will not be

discovered and the company’s long-term success

will be affected.

3. Extrinsic rewards assume people are driven by

lower-level needs. Rewards such as bonuses,

pay increases, and even praise presume that the

primary reason people initiate and persist in

behavior is to satisfy lower-level needs. How-

ever, behavior also is based on yearnings for

self-expression and on feelings of self-esteem

and self-worth. Typical individual incentive pro-

grams don’t re ect and encourage the myriad

behaviors that are motivated by people’s need

to express themselves and realize their higher

needs for growth and ful llment.

Today’s organizations need employees who are

motivated to think, experiment, and continuously

search for ways to solve new problems. Al e Kohn,

one of the most vocal critics of carrot-and-stick

approaches, offers the following advice to manag-

ers regarding how to pay employees: “Pay well, pay

fairly, and then do everything you can to get money

off people’s minds.” Indeed some evidence indicates

that money is not primarily what people work for.

Managers should understand the limits of extrinsic

motivators and work to satisfy employees’ higher,

as well as lower, needs. To be motivated, employees

need jobs that offer self-satisfaction in addition to a

yearly pay raise.

SOURCES: Alfi e Kohn, “Incentives Can Be Bad for Business,”

Inc. (January 1998): 93–94; A. J. Vogl, “Carrots, Sticks, and Self-

Deception” (an interview with Alfi e Kohn), Across the Board

(January 1994): 39–44; Geoffrey Colvin, “What Money Makes

You Do,” Fortune (August 17, 1998): 213–214; and Jeffrey

Pfeffer, “Sins of Commission,” Business 2.0 (May 2004): 56.

The Carrot-and-Stick Controversy

Manager’sShoptalk

absenteeism, and unionization. Job simpli cation is compared with job rotation and

job enlargement in Exhibit 15.7.

Job Rotation

Job rotation systematically moves employees from one job to another, thereby

increasing the number of different tasks an employee performs without increasing

the complexity of any one job. For example, an autoworker might install windshields

j

j

j

j

j

jo

jo

job

rotation A

j

ob desi

g

n

th

h

a

at

at

t

t

t

at

s

s

sy

y

s

s

tematicall

y

moves emplo

y-

e

e

e

ee

es

ee

es

e

fr

fr

om

om

one

one

jo

jo

bt

b

t

oa

o

a

not

not

her

her

to

to

p

p

p

p

ro

p

ro

p

vid

vid

et

e

t

hem

hem

wi

wi

th

th

var

var

iet

iet

ya

y

a

nd

nd

s

s

st

ti

s

s

st

ti

s

mul

mul

ati

ati

on

on

.

PART 5 LEADING456

one week and front bumpers the next. Job rotation still takes advantage of engineer-

ing ef ciencies, but it provides variety and stimulation for employees. Although

employees might nd the new job interesting at rst, the novelty soon wears off as

the repetitive work is mastered.

Companies such as Home Depot, Motorola, 1-800-Flowers, and Dayton Hudson

have built on the notion of job rotation to train a exible workforce. As companies

break away from ossi ed job categories, workers can perform several jobs, thereby

reducing labor costs and giving people opportunities to develop new skills. At Home

Depot, for example, workers scattered throughout the company’s vast chain of stores

can get a taste of the corporate climate by working at in-store support centers, while

associate managers can dirty their hands out on the sales oor.

40

Job rotation also

gives companies greater exibility. One production worker might shift among the

jobs of drill operator, punch operator, and assembler, depending on the company’s

need at the moment. Some unions have resisted the idea, but many now go along,

realizing that it helps the company be more competitive.

41

Job Enlargement

Job enlargement combines a series of tasks into one new, broader job. This type of design

is a response to the dissatisfaction of employees with oversimpli ed jobs. Instead of

only one job, an employee may be responsible for three or four and will have more time

to do them. Job enlargement provides job variety and a greater challenge for employees.

At Maytag, jobs were enlarged when work was redesigned so that workers assembled

an entire water pump rather than doing each part as it reached them on the assembly

line. Similarly, rather than just changing the oil at a Precision Tune location, a mechanic

changes the oil, greases the car, airs the tires, checks uid levels, battery, air lter, and so

forth. Then, the same employee is responsible for consulting with the customer about

routine maintenance or any problems he or she sees with the vehicle.

Job Enrichment

Recall the discussion of Maslow’s need hierarchy and Herzberg’s two-factor theory.

Rather than just changing the number and frequency of tasks a worker performs, job

enrichment incorporates high-level motivators into the work, including job respon-

sibility, recognition, and opportunities for growth, learning, and achievement. In an

enriched job, employees have control over the resources necessary for performing

it, make decisions on how to do the work, experience personal growth, and set their

own work pace. Research shows that when jobs are designed to be controlled more

by employees than by managers, people typically feel a greater sense of involvement,

commitment, and motivation, which in turn contributes to higher morale, lower turn-

over, and stronger organizational performance.

42

Many companies have undertaken job enrichment programs to increase employ-

ees’ involvement, motivation, and job satisfaction. At Ralcorp’s cereal manufacturing

EXHIBIT 15.7 Types of Job Design

j

j

j

j

j

jo

jo

job

en

l

ar

g

emen

t

A

j

j

o

b

d

es

ign

gn

n

n

n

g

t

t

t

h

ha

h

ha

t

t

t

tc

t

c

omb

omb

ine

ine

sa

s

a

se

se

rie

rie

so

s

o

ft

f

t

ask

ask

s

s

i

i

in

n

n

n

to one new

b

,

b

roa

d

d

er jo

b

b

to

g

g

g

g

gi

i

ve employees variety and

c

c

c

c

ch

h

allenge

.

j

j

j

j

j

j

o

b

enric

h

ment A jo

b

d

esig

n

n

t

t

t

h

h

h

at incorporates ac

h

ievement

,

,

r

r

r

r

re

e

cognition, an

d

ot

h

er

h

ig

h

-

l

l

le

e

e

e

vel motivators into the work.

CHAPTER 15 MOTIVATING EMPLOYEES 457

5

Leading

plant in Sparks, Nevada, for example, assembly-line employees screen, interview,

and train all new hires. They are responsible for managing the production ow to

and from their upstream and downstream partners, making daily decisions that

affect their work, managing quality, and contributing to continuous improvement.

Enriched jobs have improved employee motivation and satisfaction, and the com-

pany has bene ted from higher long-term productivity, reduced costs, and happier,

more motivated employees.

43

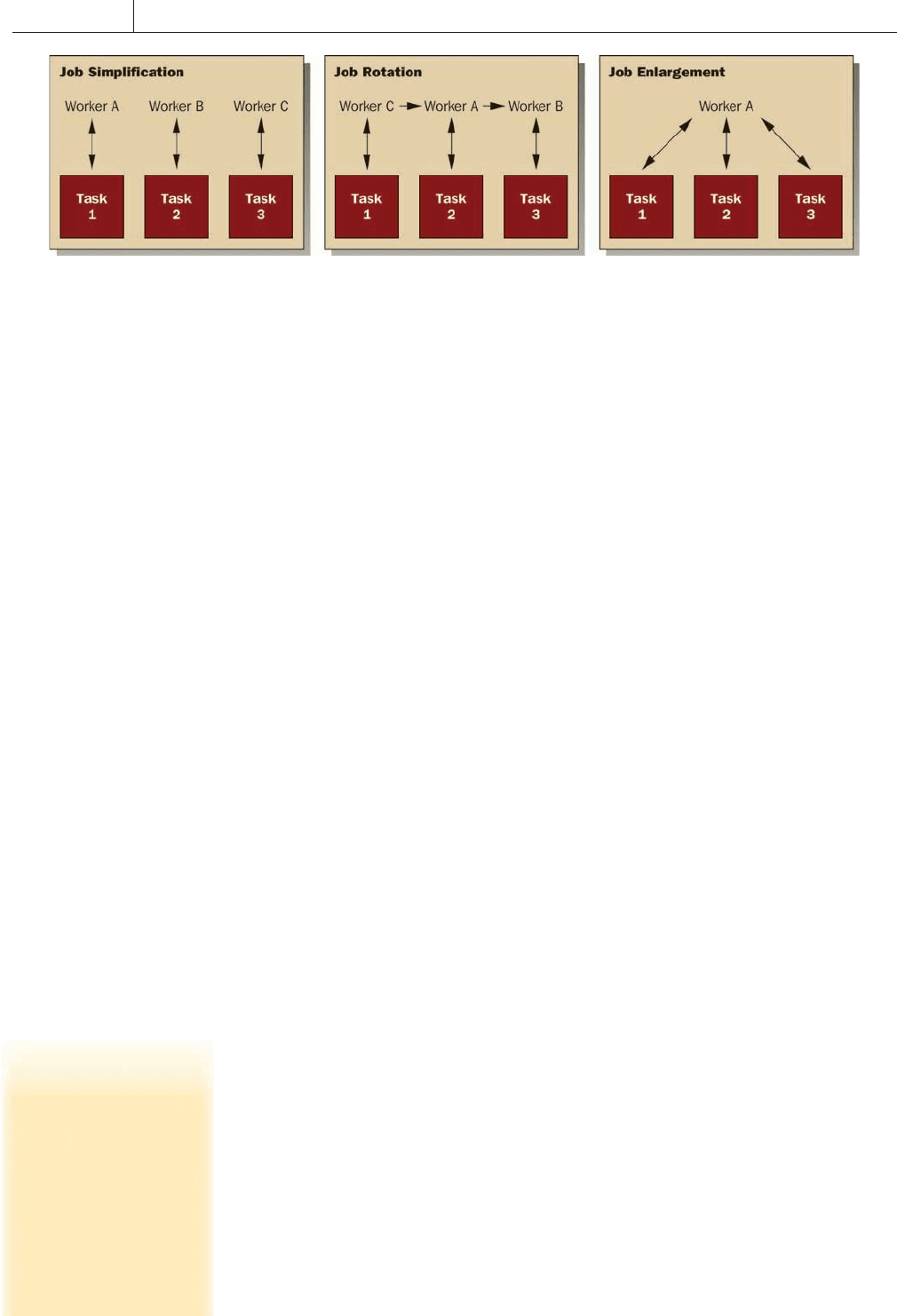

Job Characteristics Model

One signi cant approach to job design is the job characteristics model developed

by Richard Hackman and Greg Oldham.

44

Hackman and Oldham’s research con-

cerned work redesign, which is de ned as altering jobs to increase both the qual-

ity of employees’ work experience and their productivity. Hackman and Oldham’s

research into the design of hundreds of jobs yielded the job characteristics model,

which is illustrated in Exhibit 15.8. The model consists of three major parts: core job

dimensions, critical psychological states, and employee growth-need strength.

Core Job Dimensions Hackman and Oldham identi ed ve dimensions that

determine a job’s motivational potential:

1. Skill variety. The number of diverse activities that compose a job and the number

of skills used to perform it. A routine, repetitious assembly-line job is low in vari-

ety, whereas an applied research position that entails working on new problems

every day is high in variety.

2. Task identity. The degree to which an employee performs a total job with a recog-

nizable beginning and ending. A chef who prepares an entire meal has more task

identity than a worker on a cafeteria line who ladles mashed potatoes.

3. Task signi cance. The degree to which the job is perceived as important and hav-

ing impact on the company or consumers. People who distribute penicillin and

other medical supplies during times of emergencies would feel they have signi -

cant jobs.

4. Autonomy. The degree to which the worker has freedom, discretion, and self-

determination in planning and carrying out tasks. A house painter can determine

how to paint the house; a paint sprayer on an assembly line has little autonomy.

EXHIBIT 15.8 The Job Characteristics Model

SOURCE: Adapted from J. Richard Hackman and G. R. Oldham, “Motivation through the Design of Work: Test of a Theory,” Organizational Behavior and

Human Performance 16 (1976): 256.

w

w

w

w

w

wor

k redesign

T

he alterin

g

o

o

o

o

f

j

obs to increase both the

q

q

q

q

q

ua

q

q

q

l

l

it

y

o

f

f

e

l

mp

l

o

y

e

’

es

’

wo

k

r

k

ex-

p

p

p

p

p

er

p

p

p

i

i

ence

d

an

d

h

t

h

i

e

i

r pr

d

o

d

u

i

ct

i

i

v

i

t

y

y.

j

j

j

j

j

j

ob characteristics model

A

A

A

A

m

m

m

m

m

m

odel of

j

ob desi

g

n that compri

s

s-

-

-

-

e

e

e

e

es

s

core

j

ob dimensions, critical

p

p

p

p

p

sy

p

cholo

g

ical states, and em-

p

p

pl

plo

plo

plo

lo

p

p

p

p

yee

y

g

r

g

owt

h

-nee

d

stren

gth

gth

.

.

PART 5 LEADING458

5. Feedback. The extent to which doing the job provides information back to the

employee about his or her performance. Jobs vary in their ability to let workers

see the outcomes of their efforts. A football coach knows whether the team won

or lost, but a basic research scientist may have to wait years to learn whether a

research project was successful.

The job characteristics model says that the more these ve core characteristics can

be designed into the job, the more the employees will be motivated and the higher

will be performance, quality, and satisfaction.

Critical Psychological States The model posits that core job dimensions are

more rewarding when individuals experience three psychological states in response

to job design. In Exhibit 15.8, skill variety, task identity, and task signi cance tend

to in uence the employee’s psychological state of experienced meaningfulness of work.

The work itself is satisfying and provides intrinsic rewards for the worker. The job

characteristic of autonomy in uences the worker’s experienced responsibility. The job

characteristic of feedback provides the worker with knowledge of actual results. The

employee thus knows how he or she is doing and can change work performance to

increase desired outcomes.

Personal and Work Outcomes The impact of the ve job characteristics on the

psychological states of experienced meaningfulness, responsibility, and knowledge

of actual results leads to the personal and work outcomes of high work motivation,

high work performance, high satisfaction, and low absenteeism and turnover.

Employee Growth-Need Strength The nal component of the job character-

istics model is called employee growth-need strength, which means that people have

different needs for growth and development. If a person wants to satisfy low-level

needs, such as safety and belongingness, the job characteristics model has less

effect. When a person has a high need for growth and development, including

the desire for personal challenge, achievement, and challenging work, the model

is especially effective. People with a high need to grow and expand their abilities

respond favorably to the application of the model and to improvements in core job

dimensions.

One interesting nding concerns the cross-cultural differences in the impact of job

characteristics. Intrinsic factors such as autonomy, challenge, achievement, and rec-

ognition can be highly motivating in countries such as the United States. However,

they may contribute little to motivation and satisfaction in a country such as Nigeria

and might even lead to demotivation. A recent study indicates that the link between

intrinsic characteristics and job motivation and satisfaction is weaker in economi-

cally disadvantaged countries with poor governmental social welfare systems, and in

high power distance countries, as de ned in Chapter 4.

45

Thus, the job characteristics

model would be expected to be less effective in these countries.

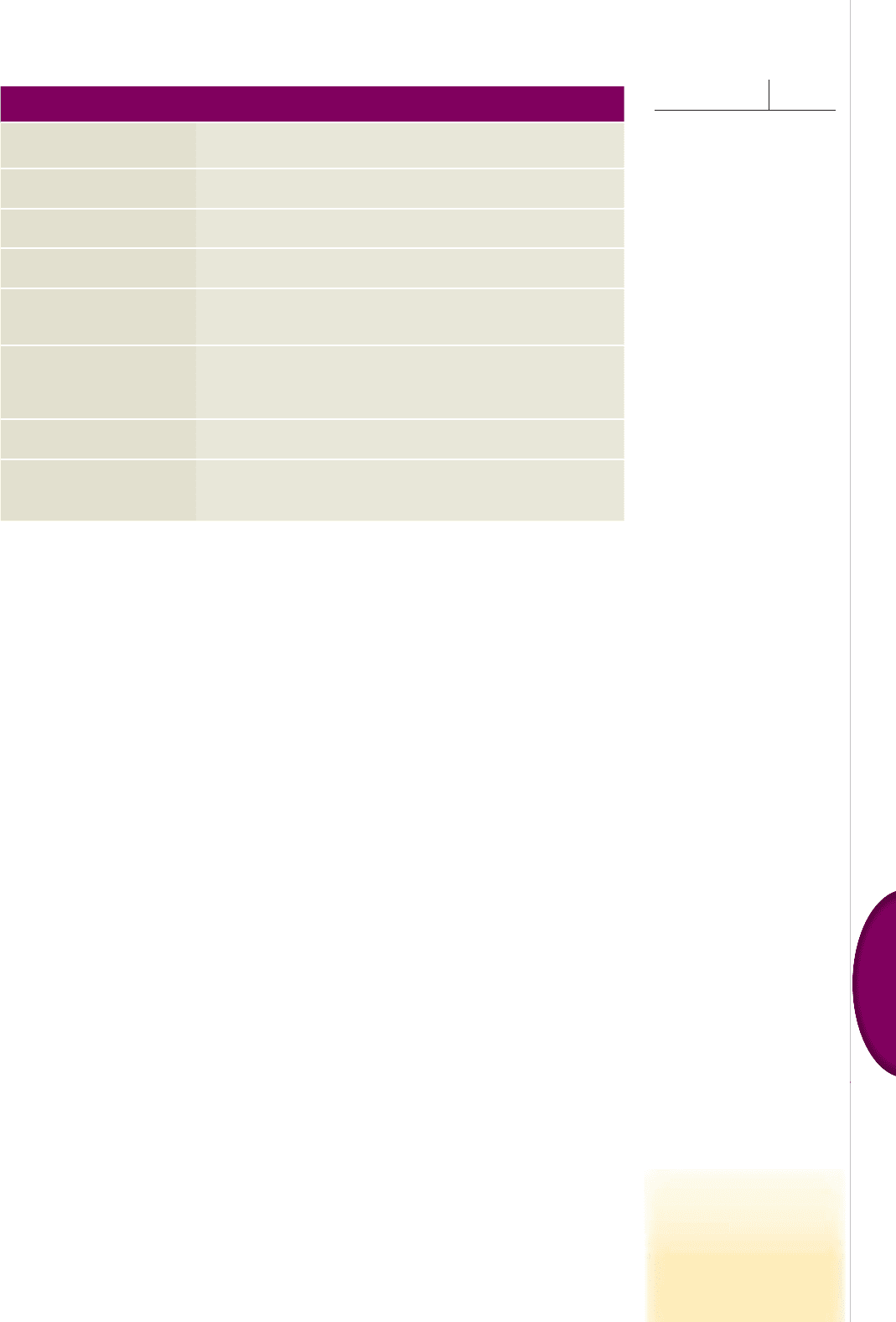

INNOVATIVE IDEAS FOR MOTIVATING

Despite the controversy over carrot-and-stick motivational practices discussed in

the Shoptalk box earlier in this chapter, organizations are increasingly using various

types of incentive compensation as a way to motivate employees to higher levels of

performance. Exhibit 15.9 summarizes several popular methods of incentive pay.

Go to the ethical dilemma on pages 464–465 that pertains to the use of incentive

compensation as a motivational tool.

TakeaMoment

CHAPTER 15 MOTIVATING EMPLOYEES 459

5

Leading

Variable compensation and forms of “at risk” pay are key motivational tools that

are becoming more common than xed salaries at many companies. These programs

can be effective if they are used appropriately and combined with motivational ideas

that also provide employees with intrinsic rewards and meet higher-level needs.

Effective managers don’t use incentive plans as the sole basis of motivation. The most

effective motivational programs typically involve much more than money or other

external rewards. Two recent motivational trends are empowering employees and

framing work to have greater meaning.

Empowering People to Meet Higher Needs

One signi cant way managers can meet higher motivational needs is to shift power

down from the top of the organization and share it with employees to enable them to

achieve goals. Empowerment is power sharing, the delegation of power or authority

to subordinates in an organization.

46

Increasing employee power heightens motiva-

tion for task accomplishment because people improve their own effectiveness, choos-

ing how to do a task and using their creativity.

47

Research indicates that most people

have a need for self-ef cacy, which is the capacity to produce results or outcomes, to

feel that they are effective.

48

Empowering employees involves giving them four elements that enable them

to act more freely to accomplish their jobs: information, knowledge, power, and

rewards.

49

1. Employees receive information about company performance. In companies where

employees are fully empowered, all employees have access to all nancial and

operational information.

2. Employees have knowledge and skills to contribute to company goals. Companies

use training programs and other development tools to help employees acquire

the knowledge and skills they need to contribute to organizational performance.

3. Employees have the power to make substantive decisions. Empowered employ-

ees have the authority to directly in uence work procedures and organizational

performance, such as through quality circles or self-directed work teams.

Program Purpose

Pay for performance Rewards individual employees in proportion to their performance

contributions. Also called merit pay.

Gain sharing Rewards all employees and managers within a business unit when

predetermined performance targets are met. Encourages teamwork.

Employee stock ownership

plan (ESOP)

Gives employees part ownership of the organization, enabling them

to share in improved profi t performance.

Lump-sum bonuses Rewards employees with a one-time cash payment based on

performance.

Pay for knowledge Links employee salary with the number of task skills acquired.

Workers are motivated to learn the skills for many jobs, thus in-

creasing company fl exibility and effi ciency.

Flexible work schedule Flextime allows workers to set their own hours. Job sharing allows two

or more part-time workers to jointly cover one job. Telecommuting,

sometimes called fl ex-place, allows employees to work from home or

an alternative workplace.

Team-based compensation Rewards employees for behavior and activities that benefi t the

team, such as cooperation, listening, and empowering others.

Lifestyle awards Rewards employees for meeting ambitious goals with luxury items,

such as high-defi nition televisions, tickets to big-name sporting

events, and exotic travel.

EXHIBIT 15.9

New Motivational Compen-

sation Programs

e

e

e

e

e

emp

owermen

t

T

h

e

d

e

l

ega

-

t

t

t

i

i

on o

f

p

p

ower an

d

aut

h

orit

y

y

to

s

s

s

su

u

b

s

s

ordinates.