Richard L. Daft - Management. 9th ed., 2010

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

PART 4 ORGANIZING290

5. Meet with leaders, who are asked to respond to recommendations on the spot.

6.

Hold additional meetings as needed to implement the recommendations.

7. Start the process all over again with a new process or problem.

GE’s Work-Out process forces a rapid analysis of ideas, the creation of solutions, and

the development of a plan for implementation. Over time, this large-group process creates

an organizational culture where ideas are rapidly translated into action and positive business

results.

57

Large-group interventions represent a signi cant shift in the way leaders think

about change and re ect an increasing awareness of the importance of dealing with

the entire system, including external stakeholders, in any signi cant change effort.

As a new manager, look for and implement training opportunities that can help

people shift their attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors toward what is needed for team,

department, and organization success. Use organization development consultants

and techniques such as team building, survey feedback, and large-group intervention

for widespread change.

OD Steps Organization development experts acknowledge that changes in corpo-

rate culture and human behavior are tough to accomplish and require major effort.

The theory underlying OD proposes three distinct stages for achieving behavioral

and attitudinal change: (1) unfreezing, (2) changing, and (3) refreezing.

58

The rst stage, unfreezing, means that people throughout the organization are

made aware of problems and the need for change. This stage creates the motiva-

tion for people to change their attitudes and behaviors. Unfreezing may begin when

managers present information that shows discrepancies between desired behaviors

or performance and the current state of affairs. In addition, managers need to estab-

lish a sense of urgency to unfreeze people and create an openness and willingness to

change. The unfreezing stage is often associated with diagnosis, which uses an outside

expert called a change agent. The change agent is an OD specialist who performs a

systematic diagnosis of the organization and identi es work-related problems. He

or she gathers and analyzes data through personal interviews, questionnaires, and

observations of meetings. The diagnosis helps determine the extent of organizational

problems and helps unfreeze managers by making them aware of problems in their

behavior.

The second stage, changing, occurs when individuals experiment with new

behavior and learn new skills to be used in the workplace. This process is sometimes

known as intervention, during which the change agent implements a speci c plan

for training managers and employees. The changing stage might involve a number

of speci c steps.

59

For example, managers put together a coalition of people with the

will and power to guide the change, create a vision for change that everyone can

believe in, and widely communicate the vision and plans for change throughout the

company. In addition, successful change involves using emotion as well as logic to

persuade people and empowering employees to act on the plan and accomplish the

desired changes.

The third stage, refreezing, occurs when individuals acquire new attitudes or val-

ues and are rewarded for them by the organization. The impact of new behaviors

is evaluated and reinforced. The change agent supplies new data that show posi-

tive changes in performance. Managers may provide updated data to employees

that demonstrate positive changes in individual and organizational performance.

Top executives celebrate successes and reward positive behavioral changes. At this

stage, changes are institutionalized in the organizational culture, so that employees

begin to view the changes as a normal, integral part of how the organization oper-

ates. Employees may also participate in refresher courses to maintain and reinforce

the new behaviors.

TakeaMoment

u

u

u

u

u

unf

reezin

g

T

h

e stage o

f

o

o

o

o

rganization

d

eve

l

opment in

w

w

w

w

w

w

hi

w

ch

p

artici

p

ants are made

a

a

a

aw

w

a

a

re of

p

roblems to increase

t

t

t

th

h

eir willin

g

ness to chan

g

e

t

t

t

th

he

ir

be

h

a

vi

o

r.

c

c

c

c

han

g

e a

g

en

t

An

O

D

s

s

s

sp

pe

sp

pe

cia

cia

lis

lis

tw

t

w

ho

ho

con

con

tra

tra

cts

cts

wi

wi

th

th

a

a

a

a

an

n

a

or

g

anization to facilitate

c

c

c

ch

h

ch

h

a

c

n

g

e.

c

c

c

c

han

g

in

g

Th

e intervention

s

s

s

s

st

t

age o

f

organization

d

eve

l

op-

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

ent in which individuals ex

-

p

p

p

p

p

p

eriment with new work

p

lace

b

b

b

b

b

b

e

h

a

vi

o

r.

r

r

r

r

efreezin

g

T

h

e rein

f

orcemen

t

t

t

s

s

s

s

st

t

age o

f

organization

d

eve

l

op-

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

ent in which individuals

a

a

a

a

ac

cq

uire a desired new skill or

a

a

a

a

at

tt

i

tude

a

n

d

a

r

e

r

e

w

a

r

ded

f

o

r i

t

t

b

b

b

b

b

by

y

the or

g

anization.

CHAPTER 10 MANAGING CHANGE AND INNOVATION 291

4

Organizing

IMPLEMENTING CHANGE

The nal step to be managed in the change process is implementation. A new, creative

idea will not bene t the organization until it is in place and being fully used. Execu-

tives at companies around the world are investing heavily in change and innovation

projects, but many of them say they aren’t very happy with their results.

60

One frus-

tration for managers is that employees often seem to resist change for no apparent

reason. To effectively manage the implementation process, managers should be aware

of the reasons people resist change and use techniques to enlist employee coopera-

tion. Major, corporate-wide changes can be particularly challenging, as discussed in

the Manager’s Shoptalk box.

Need for Change

Many people are not willing to change

unless they perceive a problem or a crisis.

However, many problems are subtle, so

managers have to recognize and then make

others aware of the need for change.

61

One way managers sense a need for

change is through the appearance of a

performance gap—a disparity between

existing and desired performance levels.

They then try to create a sense of urgency

so that others in the organization will rec-

ognize and understand the need for change

(similar to the OD concept of unfreezing).

Recall from Chapter 7 the discussion of

SWOT analysis. Managers are responsible

for monitoring threats and opportuni-

ties in the external environment as well

as strengths and weaknesses within the

organization to determine whether a need

for change exists. Big problems are easy

to spot, but sensitive monitoring systems

are needed to detect gradual changes that

can fool managers into thinking their com-

pany is doing ne. An organization may

be in greater danger when the environment

changes slowly, because managers may fail

to trigger an organizational response.

Resistance to Change

Getting others to understand the need for change is the rst step in implementation. Yet

most changes will encounter some degree of resistance. Idea champions often discover

that other employees are unenthusiastic about their new ideas. Members of a new-

venture group may be surprised when managers in the regular organization do not

support or approve their innovations. Managers and employees not involved in an

innovation often seem to prefer the status quo. People resist change for several reasons,

and understanding them can help managers implement change more effectively.

Self-Interest People typically resist a change they believe con icts with their self-in-

terests. A proposed change in job design, structure, or technology may lead to an increase

in employees’ workload, for example, or a real or perceived loss of power, prestige, pay,

or bene ts. The fear of personal loss is perhaps the biggest obstacle to organizational

Fear of job loss is one of the biggest reasons for

resistance to change. Managers at Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. decided the company

needed to outsource some of its private label business to compete with low-cost

foreign producers. Unfortunately, the change would lead to plant closings in the

U.S. After having made major concessions several years earlier to help the ailing tire

manufacturer, United Steelworkers Union members were strongly opposed to further

job losses. Despite months of talks, the two sides failed to reach an agreement and

15,000 USW members went on strike.

© MARK DUNCAN/ASSOCIATED PRESS

p

p

p

p

p

per

f

ormance

g

ap

A

d

ispari

ty

ty

y

y

y

b

b

b

b

b

etween existing an

d

d

esire

d

p

p

p

p

p

er

p

p

f

ormance

l

eve

l

s

.

PART 4 ORGANIZING292

Employees are not always receptive to change. A

combination of factors can lead to rejection of, or

even outright rebellion against, management’s “new

and better ideas.”

Consider what happened when managers at

Lands’ End Inc. of Dodgeville, Wisconsin, tried to

implement a sweeping overhaul incorporating many

of today’s management trends—teams, 401(k) plans,

peer reviews, and the elimination of guards and time

clocks. Despite managers’ best efforts, employees

balked. They had liked the old family-like atmosphere

and uncomplicated work environment, and they con-

sidered the new requirement for regular meetings a

nuisance. “We spent so much time in meetings that

we were getting away from the basic stuff of taking

care of business,” says one employee. Even a much-

ballyhooed new mission statement seemed “pushy.”

One long-time employee complained, “We don’t

need anything hanging over our heads telling us to

do something we’re already doing.”

Confusion and frustration reigned at Lands’ End

and was re ected in an earnings drop of 17 percent.

Eventually, a new CEO initiated a return to the famil-

iar “Lands’ End Way” of doing things. Teams were

disbanded, and many of the once-promising initiatives

were shelved as workers embraced what was familiar.

The inability of people to adapt to change is not

new. Neither is the failure of management to suf ciently

lay the groundwork to prepare employees for change.

Harvard professor John P. Kotter established an eight-step

plan for implementing change that can provide a greater

potential for successful transformation of a company:

1. Establish a sense of urgency through careful

examination of the market and identi cation of

opportunities and potential crises.

2. Form a powerful coalition of managers able to

lead the change.

3. Create a vision to direct the change and the strat-

egies for achieving that vision.

4. Communicate the vision throughout the

organization.

5. Empower others to act on the vision by remov-

ing barriers, changing systems, and encouraging

risk taking.

6. Plan for and celebrate visible, short-term perfor-

mance improvements.

7. Consolidate improvements, reassess changes,

and make necessary adjustments in the new

programs.

8. Articulate the relationship between new behav-

iors and organizational success.

Major change efforts can be messy and full of sur-

prises, but following these guidelines can break

down resistance and mean the difference between

success and failure.

SOURCES: Gregory A. Patterson, “Lands’ End Kicks Out

Modern New Managers, Rejecting a Makeover,” The Wall

Street Journal, April 3, 1995; and John P. Kotter, “Leading

Changes: Why Transformation Efforts Fail,” Harvard Business

Review (March–April 1995): 59–67.

Making Change Stick

Manager’sShoptalk

change.

62

At Fabcon, which makes huge precast con-

crete wall panels for commercial buildings, employ-

ees resisted a new experimental automation process

because it added to their workload and reduced their

productivity. “They were already working long days;

they want to go home, and they didn’t want to spend

time doing R &D,” says Fabcon’s CEO Michael Le

Jeune.

63

Managers began working with the foremen to

show them how the process could eventually save time

and effort, and the change was eventually a success.

Lack of Understanding and Trust Employees

often distrust the intentions behind a change or do not

understand the intended purpose of a change. If pre-

vious working relationships with an idea champion

have been negative, resistance may occur. One man-

ager had a habit of initiating a change in the nancial

reporting system about every 12 months and then los-

ing interest and not following through. After the third

Marathon Oil Corporation took a

creative approach to implementing change by using this Discovery

Map to engage all 2,400 or so employees in the switch to using

a new enterprise resource planning system. The ERP software

system from SAP would impact all employees and operations at

the international oil and gas production company and was seen as

critical to the company’s future competitiveness. Paradigm Learning,

Inc., a Florida-based consulting fi rm, created the Discovery Map

that visually communicates Marathon’s change initiatives: its current

reality and challenges, its vision for the future, and how to get there

from here—with the new ERP system shown as the bridge.

© PARADIGM LEARNING’S DISCOVERY

MAP ® ON IMPLEMENTING CHANGE

AT MARATHON OIL

CHAPTER 10 MANAGING CHANGE AND INNOVATION 293

4

Organizing

time, employees no longer went along with the change because they did not trust the

manager’s intention to follow through to their bene t.

Uncertainty Uncertainty is the lack of information about future events. It represents a

fear of the unknown. Uncertainty is especially threatening for employees who have a

low tolerance for change and fear anything out of the ordinary. They do not know how a

change will affect them and worry about whether they will be able to meet the demands

of a new procedure or technology.

64

For example, union leaders at an American auto

manufacturer resisted the introduction of employee participation programs. They were

uncertain about how the program would affect their status and thus initially opposed it.

Different Assessments and Goals Another reason for resistance to change is

that people who will be affected by an innovation may assess the situation differently

from an idea champion or new-venture group. Critics frequently voice legitimate dis-

agreements over the proposed bene ts of a change. Managers in each department

pursue different goals, and an innovation may detract from performance and goal

achievement for some departments. For example, if marketing gets the new product

it wants for customers, the cost of manufacturing may increase, and the manufactur-

ing superintendent thus will resist. Resistance may call attention to problems with the

innovation. At a consumer products company in Racine, Wisconsin, middle managers

resisted the introduction of a new employee program that turned out to be a bad idea.

The managers truly believed that the program would do more harm than good.

65

These reasons for resistance are legitimate in the eyes of employees affected by

the change. The best procedure for managers is not to ignore resistance but to diag-

nose the reasons and design strategies to gain acceptance by users.

66

Strategies for

overcoming resistance to change typically involve two approaches: the analysis of

resistance through the force- eld technique and the use of selective implementation

tactics to overcome resistance.

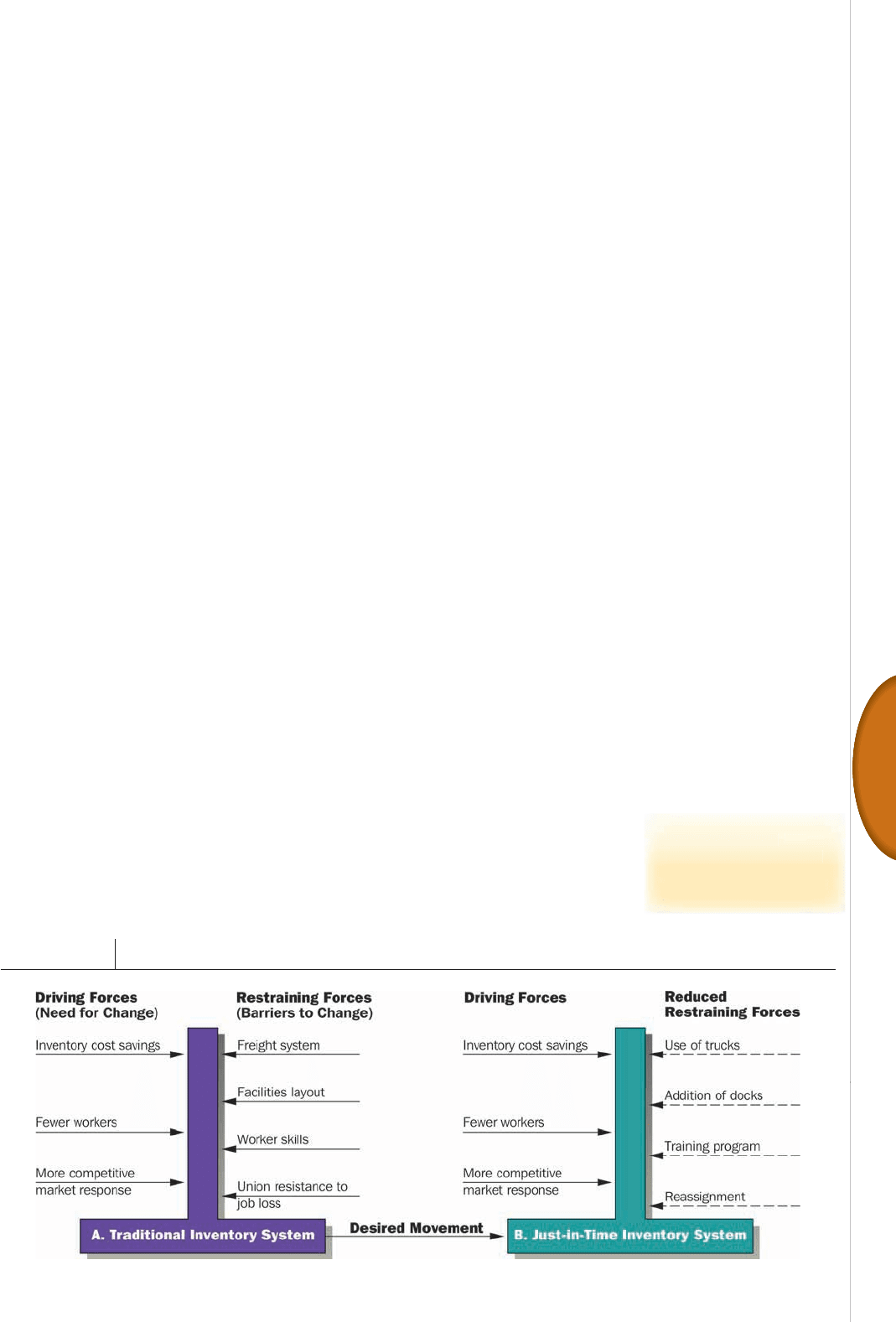

Force-Field Analysis

Force- eld analysis grew from the work of Kurt Lewin, who proposed that change was

a result of the competition between driving and restraining forces.

67

Driving forces can

be thought of as problems or opportunities that provide motivation for change within

the organization. Restraining forces are the various barriers to change, such as a lack

of resources, resistance from middle managers, or inadequate employee skills. When

a change is introduced, management should analyze both the forces that drive change

(problems and opportunities) as well as the forces that resist it (barriers to change). By

selectively removing forces that restrain change, the driving forces will be strong enough

to enable implementation, as illustrated by the move from A to B in Exhibit 10.7. As bar-

riers are reduced or removed, behavior will shift to incorporate the desired changes.

EXHIBIT 10.7 Using Force-Field Analysis to Change from Traditional to Just-in-Time Inventory System

f

f

f

f

fo

fo

for

ce-fi eld analysis Th

e

e

p

p

p

p

p

ro

p

p

p

p

p

cess o

fd

f

d

t

e

t

e

i

rm

i

i

n

i

n

g

w

g

hi

hi

c

h

h

f

f

f

fo

o

o

r

ces

d

riv

e

a

n

d

whi

c

h r

es

i

st

a

p

p

p

pr

pro

pro

pro

ro

p

p

pos

p

ed chan

g

e

g

.

PART 4 ORGANIZING294

Just-in-time (JIT) inventory control systems schedule materials to arrive at a

company just as they are needed on the production line. In an Ohio manufactur-

ing company, management’s analysis showed that the driving forces (opportuni-

ties) associated with the implementation of JIT were: (1) the large cost savings from

reduced inventories, (2) savings from needing fewer workers to handle the inventory,

and (3) a quicker, more competitive market response for the company. Restraining

forces (barriers) discovered by managers were: (1) a freight system that was too slow

to deliver inventory on time, (2) a facility layout that emphasized inventory mainte-

nance over new deliveries, (3) worker skills inappropriate for handling rapid inven-

tory deployment, and (4) union resistance to loss of jobs. The driving forces were not

suf cient to overcome the restraining forces.

To shift the behavior to JIT, managers attacked the barriers. An analysis of the

freight system showed that delivery by truck provided the exibility and quickness

needed to schedule inventory arrival at a speci c time each day. The problem with

facility layout was met by adding four new loading docks. Inappropriate worker

skills were attacked with a training program to instruct workers in JIT methods and

in assembling products with uninspected parts. Union resistance was overcome by

agreeing to reassign workers no longer needed for maintaining inventory to jobs in

another plant. With the restraining forces reduced, the driving forces were suf cient

to allow the JIT system to be implemented.

As a new manager, recognize that people often have legitimate and rational reasons

for resisting change. Don’t try to bulldoze a change through a wall of resistance. Use

force-fi eld analysis to evaluate the forces that are driving a change and those that are

restraining it. Try communication and education, participation, and negotiation to

melt resistance, and be sure to enlist the support of top-level managers. Use coercion

to implement a change only when absolutely necessary.

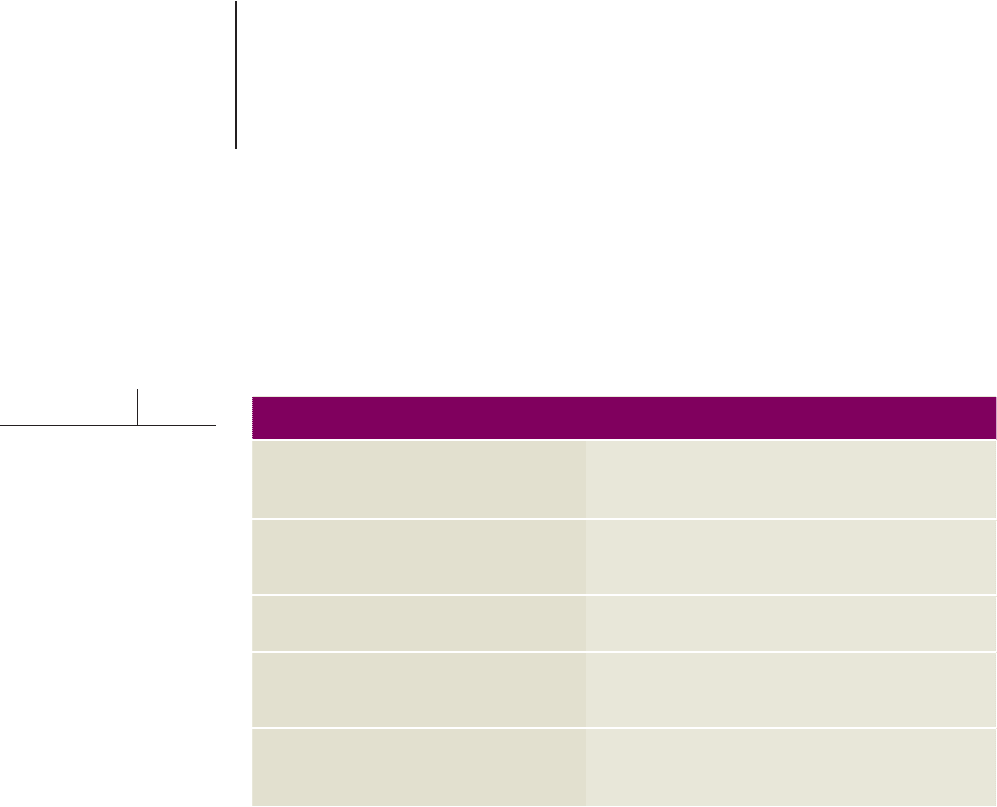

Implementation Tactics

The other approach to managing implementation is to adopt speci c tactics to over-

come resistance. Researchers have studied various methods for dealing with resis-

tance to change. The following ve tactics, summarized in Exhibit 10.8, have proven

successful.

68

TakeaMoment

EXHIBIT 10.8

Tactics for Overcoming

Resistance to Change

Approach When to Use

Communication, education • Change is technical.

• Users need accurate information and analysis to

understand change.

Participation

• Users need to feel involved.

• Design requires information from others.

• Users have power to resist.

Negotiation

• Group has power over implementation.

• Group will lose out in the change.

Coercion

• A crisis exists.

• Initiators clearly have power.

• Other implementation techniques have failed.

Top management support

• Change involves multiple departments or

reallocation of resources.

• Users doubt legitimacy of change.

SOURCE: Based on J.P. Kotter and L.A. Schlesinger,“Choosing Strategies for Change,” Harvard Business Review 57

(March–April 1979): 106–114.

CHAPTER 10 MANAGING CHANGE AND INNOVATION 295

4

Organizing

Communication and Education Communication and education are used when

solid information about the change is needed by users and others who may resist

implementation. Education is especially important when the change involves new

technical knowledge or users are unfamiliar with the idea. Canadian Airlines Inter-

national spent a year and a half preparing and training employees before chang-

ing its entire reservations, airport, cargo, and nancial systems as part of a new

“Service Quality” strategy. Smooth implementation resulted from this intensive train-

ing and communications effort, which involved 50,000 tasks, 12,000 people, and 26

classrooms around the world.

69

Managers should also remember that implementing

change requires speaking to people’s hearts (touching their feelings) as well as to

their minds (communicating facts). Emotion is a key component in persuading and

in uencing others. People are much more likely to change their behavior when they

both understand the rational reasons for doing so and see a picture of change that

in uences their feelings.

70

Participation Participation involves users and potential resisters in designing the

change. This approach is time consuming, but it pays off because users understand

and become committed to the change. At Learning Point Associates, which needed to

change dramatically to meet new challenges, the change team drew up a comprehen-

sive road map for transformation but had trouble getting the support of most manag-

ers. The managers argued that they hadn’t been consulted about the plans and didn’t

feel compelled to participate in implementing them.

71

Research studies have shown

that proactively engaging front-line employees in upfront planning and decision

making about changes that affect their work results in much smoother implementa-

tion.

72

Participation also helps managers determine potential problems and under-

stand the differences in perceptions of change among employees.

Negotiation Negotiation is a more formal means of achieving cooperation. Nego-

tiation uses formal bargaining to win acceptance and approval of a desired change.

For example, if the marketing department fears losing power if a new management

structure is implemented, top managers may negotiate with marketing to reach a

resolution. Companies that have strong unions frequently must formally negotiate

change with the unions. The change may become part of the union contract re ecting

the agreement of both parties.

Coercion Coercion means that managers use formal power to force employees to

change. Resisters are told to accept the change or lose rewards or even their jobs. In

most cases, this approach should not be used because employees feel like victims, are

angry at change managers, and may even sabotage the changes. However, coercion

may be necessary in crisis situations when a rapid response is urgent. For example, a

number of top managers at Coca-Cola had to be reassigned or let go after they refused

to go along with a new CEO’s changes for revitalizing the sluggish corporation.

73

Top Management Support The visible support of top management also helps

overcome resistance to change. Top management support symbolizes to all employees

that the change is important for the organization. One survey found that 80 percent

of companies that are successful innovators have top executives who frequently

reinforce the importance of innovation both verbally and symbolically.

74

Top man-

agement support is especially important when a change involves multiple depart-

ments or when resources are being reallocated among departments. Without top

management support, changes can get bogged down in squabbling among depart-

ments. Moreover, when change agents fail to enlist the support of top executives,

these leaders can inadvertently undercut the change project by issuing contradic-

tory orders.

PART 4 ORGANIZING296

Managers can soften resistance and facilitate change and innovation by using smart

techniques. At Remploy Ltd., needed changes were at rst frightening and confusing

to Remploy’s workers, 90 percent of whom have some sort of disability. However, by

communicating with employees, providing training, and closely involving them in

the change process, managers were able to smoothly implement the new procedures

and work methods. As machinist Helen Galloway put it, “Change is frightening, but

because we all have a say, we feel more con dent making those changes.”

75

ch10

A MANAGER’S ESSENTIALS: WHAT HAVE WE LEARNED?

▪ Change is inevitable in organizations, and successful innovation is vital to the

health of companies in all industries. This chapter discussed the techniques avail-

able for managing the change process. Two key aspects of change in organiza-

tions are changing products and technologies and changing people and culture.

▪ Three essential innovation strategies for changing products and technologies are

exploration, cooperation, and entrepreneurship. Exploration involves designing

the organization to promote creativity, imagination, and idea generation. Cooper-

ation requires mechanisms for internal coordination, such as horizontal linkages

across departments, and mechanisms for connecting with external parties. One

popular approach is open innovation, which extends the search for and com-

mercialization of ideas beyond the boundaries of the organization. Entrepreneur-

ship includes encouraging idea champions and establishing new-venture teams,

skunkworks, and new-venture funds.

▪ People and culture changes pertain to the skills, behaviors, and attitudes of

employees. Training and organization development are important approaches to

changing people’s mind-sets and corporate culture. The OD process entails three

steps: unfreezing (diagnosis of the problem), the actual change (intervention),

and refreezing (reinforcement of new attitudes and behaviors). Popular OD tech-

niques include team building, survey feedback, and large-group interventions.

▪ Implementation of change rst requires that people see a need for change.

Managers should be prepared to encounter resistance. Some typical reasons for

resistance include self-interest, lack of trust, uncertainty, and con icting goals.

Force- eld analysis is one technique for diagnosing barriers, which often can be

removed. Managers can also draw on the implementation tactics of communica-

tion, participation, negotiation, coercion, or top management support.

1. Times of shared crisis, such as the September 11,

2001, terrorist attack on the World Trade Center or

the Gulf Coast hurricanes in 2005, can induce many

companies that have been bitter rivals to put their

competitive spirit aside and focus on cooperation

and courtesy. Do you believe this type of change

will be a lasting one? Discuss.

2. A manager of an international chemical company

said that few new products in her company were

successful. What would you advise the manager to

do to help increase the company’s success rate?

3. As a manager, how would you deal with resistance

to change when you suspect employees’ fears of

job loss are well founded?

4. How might businesses use the Internet to identify

untapped customer needs through open innova-

tion? What do you see as the major advantages and

disadvantages of the open innovation approach?

5. If you were head of a police department in a mid-

sized city, which technique do you think would

be more effective for implementing changes in

patrol of cers’ daily routines to stop more cars:

ch10

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

CHAPTER 10 MANAGING CHANGE AND INNOVATION 297

4

Organizing

communication and education or proactively

engaging them through participation ?

6. Analyze the driving and restraining forces of a

change you would like to make in your life. Do

you believe understanding force- eld analysis can

help you more effectively implement a signi cant

change in your own behavior?

7. Which role or roles—the inventor, champion, spon-

sor, or critic—would you most like to play in the

innovation process? Why do you think idea champi-

ons are so essential to the initiation of change? Could

they be equally important for implementation?

8. You are a manager, and you believe the expense

reimbursement system for salespeople is far too

slow, taking weeks instead of days. How would

you go about convincing other managers that this

problem needs to be addressed?

9. Do the underlying values of organization devel-

opment differ from assumptions associated with

other types of change? Discuss.

10. How do large-group interventions differ from

OD techniques such as team building and survey

feedback?

ch10

MANAGEMENT IN PRACTICE: EXPERIENTIAL EXERCISE

Is Your Company Creative?

An effective way to assess the creative climate of an

organization for which you have worked is to ll

out the following questionnaire. Answer each ques-

tion based on your work experience in that rm.

Discuss the results with members of your group,

and talk about whether changing the rm along the

dimensions in the questions would make it more

creative.

Instructions: Answer each of the following ques-

tions using the ve-point scale (Note: No rating of 4 is

used):

0 We never do this.

1 We rarely do this.

2 We sometimes do this.

3 We frequently do this.

5 We always do this.

1. We are encouraged to seek help anywhere inside

or outside the organization with new ideas for our

work unit.

0 1 2 3 5

2. Assistance is provided to develop ideas into pro-

posals for management review.

0 1 2 3 5

3. Our performance reviews encourage risky, cre-

ative efforts, ideas, and actions.

0 1 2 3 5

4. We are encouraged to ll our minds with new

information by attending professional meetings

and trade fairs, visiting customers, and so on.

0 1 2 3 5

5. Our meetings are designed to allow people to free-

wheel, brainstorm, and generate ideas.

0 1 2 3 5

6. All members contribute ideas during meetings.

0 1 2 3 5

7. Meetings often involve much spontaneity and

humor.

0 1 2 3 5

8. We discuss how company structure and our

actions help or spoil creativity within our work

unit.

0 1 2 3 5

9. During meetings, the chair is rotated among

members.

0 1 2 3 5

10. Everyone in the work unit receives training in

creativity techniques and maintaining a creative

climate.

0 1 2 3 5

Scoring and Interpretation

Add your total score for all 10 questions: ______

To measure how effectively your organization fosters

creativity, use the following scale:

Highly effective: 35–50

Moderately effective: 20–34

Moderately ineffective: 10–19

Ineffective: 0–9

SOURCE: Adapted from Edward Glassman, Creativity Handbook: Idea

Triggers and Sparks That Work (Chapel Hill, NC: LCS Press, 1990).

Used by permission.

PART 4 ORGANIZING298

Crowdsourcing

Last year, when Ai-Lan Nguyen told her friend Greg

Barnwell that Off the Hook Tees, based in Asheville,

North Carolina, was going to experiment with

crowdsourcing, he warned her she wouldn’t like

the results. Now, as she was about to walk into a

meeting called to decide whether to adopt this new

business model, she was afraid her friend had been

right.

Crowdsourcing uses the Internet to invite anyone,

professionals and amateurs alike, to perform tasks

such as product design that employees usually per-

form. In exchange, contributors receive recognition—

but little or no pay. Ai-Lan, as vice president of

operations for Off the Hook, a company specializing

in witty T-shirts aimed at young adults, upheld the

values of founder Chris Woodhouse, who like Ai-Lan

was a graphic artist. Before he sold the company, the

founder always insisted that T-shirts be well designed

by top-notch graphic artists to make sure each screen

print was a work of art. Those graphic artists reported

to Ai-Lan.

During the past 18 months, Off the Hook’s sales

stagnated for the rst time in its history. The crowd-

sourcing experiment was the latest in a series of

attempts to jump-start sales growth. Last spring, Off

the Hook issued its rst open call for T-shirt designs

and then posted the entries on the Web so people

could vote for their favorites. The top ve vote get-

ters were handed over to the in-house designers, who

tweaked the submissions until they met the compa-

ny’s usual quality standards.

When CEO Rob Taylor rst announced the com-

pany’s foray into crowdsourcing, Ai-Lan found her-

self reassuring the designers that their positions were

not in jeopardy. Now Ai-Lan was all but certain she

would have to go back on her word. Not only had

the crowdsourced tees sold well, but Rob had put a

handful of winning designs directly into production,

bypassing the design department altogether. Custom-

ers didn’t notice the difference.

Ai-Lan concluded that Rob was ready to adopt

some form of the Web-based crowdsourcing because

it made T-shirt design more responsive to con-

sumer desires. Practically speaking, it reduced the

uncertainty that surrounded new designs, and it

dramatically lowered costs. The people who won

the competitions were delighted with the exposure it

gave them.

However, when Ai-Lan looked at the crowd-

sourced shirts with her graphic artist’s eye, she felt

that the designs were competent, but none achieved

the aesthetic standards attained by her in-house de -

signers. Crowdsourcing essentially replaced training

and expertise with public opinion. That made the art-

ist in her uncomfortable.

More distressing, it was beginning to look as if

Greg had been right when he’d told her that his work-

ing de nition of crowdsourcing was “a billion ama-

teurs want your job.” It was easy to see that if Off the

Hook adopted crowdsourcing, she would be handing

out pink slips to most of her design people, long-time

employees whose work she admired. “Sure, crowd-

sourcing costs the company less, but what about the

human cost?” Greg asked.

What future course should Ai-Lan argue for at the

meeting? And what personal decisions did she face if

Off the Hook decided to put the crowd completely in

charge when it came to T-shirt design?

What Would You Do?

1. Go to the meeting and argue for abandoning

cr

owdsourcing for now in favor of maintaining the

artistic integrity and values that Off the Hook has

always stood for.

2. Accept the reality that because Off the Hook’s CEO

Rob Taylor strongly favors crowdsourcing, it’s a

fait accompli. Be a team player and help work out

the details of the new design approach. Prepare to

lay off graphic designers as needed.

3. Accept the fact that converting Off the Hook to a

crowdsourcing business model is inevitable, but

because it violates your own personal values, start

looking for a new job elsewhere.

SOURCES: Based on Paul Boutin, “Crowdsourcing: Consumers as

Creators,” BusinessWeek Online (July 13, 2006), www.businessweek

.com/innovate/content/jul2006/id20060713_55844.htm?campaign_id=

search; Jeff Howe, “The Rise of Crowdsourcing,” Wired (June 2006),

www.wired.com/wired/archive/14.06/crowds. html; and Jeff Howe,

Crowdsourcing Blog, www.crowdsourcing.com.

ch10

MANAGEMENT IN PRACTICE: ETHICAL DILEMMA

CHAPTER 10 MANAGING CHANGE AND INNOVATION 299

4

Organizing

Southern Discomfort

Jim Malesckowski remembers the call of two

weeks ago as if he just put down the telephone

receiver. “I just read your analysis and I want you

to get down to Mexico right away,” Jack Ripon, his

boss and chief executive officer, had blurted in his

ear. “You know we can’t make the plant in Ocon-

omo work anymore—the costs are just too high.

So go down there, check out what our operational

costs would be if we move, and report back to me

in a week.”

At that moment, Jim felt as if a shiv had been

stuck in his side, just below the rib cage. As president

of the Wisconsin Specialty Products Division of

Lamprey, Inc., he knew quite well the challenge of

dealing with high-cost labor in a third-generation,

unionized U.S. manufacturing plant. And although

he had done the analysis that led to his boss’s knee-

jerk response, the call still stunned him. There were

520 people who made a living at Lamprey’s Oconomo

facility, and if it closed, most of them wouldn’t have

a journeyman’s prayer of nding another job in the

town of 9,000 people.

Instead of the $16-per-hour average wage paid at

the Oconomo plant, the wages paid to the Mexican

workers—who lived in a town without sanitation and

with an unbelievably toxic ef uent from industrial

pollution—would amount to about $1.60 an hour on

average. That’s a savings of nearly $15 million a year

for Lamprey, to be offset in part by increased costs for

training, transportation, and other matters.

After two days of talking with Mexican govern-

ment representatives and managers of other com-

panies in the town, Jim had enough information to

develop a set of comparative gures of production

and shipping costs. On the way home, he started

to outline the report, knowing full well that unless

some miracle occurred, he would be ushering in

a blizzard of pink slips for people he had come to

appreciate.

The plant in Oconomo had been in operation since

1921, making special apparel for persons suffering

injuries and other medical conditions. Jim had often

talked with employees who would recount stories

about their fathers or grandfathers working in the

same Lamprey company plant—the last of the

original manufacturing operations in town.

But friendship aside, competitors had already

edged past Lamprey in terms of price and were

dangerously close to overtaking it in product quality.

Although both Jim and the plant manager had tried to

convince the union to accept lower wages, union lead-

ers resisted. In fact, on one occasion when Jim and

the plant manager tried to discuss a cell manufactur-

ing approach, which would cross-train employees to

perform up to three different jobs, local union leaders

could barely restrain their anger. Yet probing beyond

the fray, Jim sensed the fear that lurked under the

union reps’ gruff exterior. He sensed their vulnerabil-

ity, but could not break through the reactionary bark

that protected it.

A week has passed and Jim just submitted his

report to his boss. Although he didn’t speci cally bring

up the point, it was apparent that Lamprey could put

its investment dollars in a bank and receive a better

return than what its Oconomo operation is currently

producing.

Tomorrow, he’ll discuss the report with the CEO.

Jim doesn’t want to be responsible for the plant’s

dismantling, an act he personally believes would

be wrong as long as there’s a chance its costs can be

lowered. “But Ripon’s right,” he said to himself. “The

costs are too high, the union’s unwilling to cooperate,

and the company needs to make a better return on its

investment if it’s to continue at all. It sounds right but

feels wrong. What should I do?”

Questions

1. What forces for change are evident at the Oconomo

plant?

2. What is the primary type of change needed—

changing “things” or changing the “people and

culture?” Can the Wisconsin plant be saved by

changing things alone, by changing people and

culture, or must both be changed? Explain your

answer.

3. What do you think is the major underlying cause of

the union leaders’ resistance to change? If you were

Jim Malesckowski, what implementation tactics

would you use to try to convince union members

to change to save the Wisconsin plant?

SOURCE: Doug Wallace, “What Would You Do?” Business Ethics

(March/April 1996): 52–53. Copyright 1996 by New Mountain Media

LLC. Reproduced with permission of New Mountain Media LLC in

the format Textbook via Copyright Clearance Center.

ch10

CASE FOR CRITICAL ANALYSIS