Research methods in education (hand book)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

-

6 1 -

material). It comes from people like Sorel and Edelman. They discuss it in terms

of the political life of a nation, and point to the way that particular events in that

nation's history become special. Bastille Day to the French, and the taking of the

Winter Palace to the Russians, it's a bit harder to do for England but maybe the

Battle of Britain, or Dunkirk, as an example. These events do get a lot of attention

anyway, they are meant to have meaning for the citizens of a nation, in that sense

they are 'special'. But for political theorists it is the secondary devices which

describe them which are equally significant. It is the film, a TV repetitious

coverage, and the telling the tale again and again by many media means, which

helps build up the mystique. Telling the tale, reciting events, helps make the thing

'remade', 'different' and special. In fact there is more to this from classical

theorists, especially those on Greece, with a whole lot of stuff about 'Kerygma'

which might I suppose be relevant, it's all about events - real events, being seen as

revealing underlying purposes and directions. In a people like the British, who

have been very affected by Judaic-Christian and then Darwinian notions of

onward progress and purpose underlying it, we might be able to see something of

that socialisation. Anyway that may be getting too fanciful. You may think the

whole thing is too fanciful.

(Measor, 1983, personal communication)

The research team did not consider the idea fanciful. In fact Pat Sikes was able to provide further

substantiation from her own data and the theme was written up as one of the key features of a teacher's

career. Discovery of the theme was made possible by certain clues – repetition of the incident, use of the

same words. There is also something special about the words used, which put one on the alert.

Other clues might be irregularities that one observes, strange events, certain things that people say

and the way they say them, things that get people excited, angry, surprised. In the researcher is the

recognition that 'something is up', prompting the use of a 'detective's nose' for putting the available pieces

of the jigsaw together to form a larger, more meaningful picture. For example, Measor and Woods were

cued in to the importance of the myths that surrounded school transfer because a number of pupils

prefaced their comments with remarks such as: 'I have heard that …'; 'They tell me that …'; 'There is this

story that …'. Clearly, these accounts were connected and there was a special quality to them (Measor and

Woods, 1984).

In The Divided School, Woods's (1979) examination of 'teacher survival' led to the theory that, in

situations where constraints on action exceeded the expectations of strong commitment, a struggle for

survival would result. It was initiated by some observations of what appeared to be very strange

behaviour. One of these was a chemistry lesson where the teacher taught for seventy minutes, complete

with experiment and blackboard work, while the pupils manifestly ignored him. They were clearly doing

other things. Only in the last ten minutes of the lesson did they dutifully record the results in their

exercise books at his dictation. In another instance, a teacher showed a class a film, even though it was

the wrong film that had been delivered and had nothing remotely to do with the subject. Such events

seemed to cry out for explanation. Why did people behave in these strange ways? Inconsistencies and

contrasts are other matters that arouse interest. Why, for example, should teachers change character so

completely between staffroom and classroom, as Lacey noted? Why do they lay claim to certain values

and beliefs in the one situation and act out values and beliefs of strong contrast in another? Why do they

behave with such irrationality and such pettiness on occasions? Why do pupils 'work' with one teacher

and 'raise hell' with another, as Turner (1983) noted? From this latter observation, Turner came to certain

conclusions about pupils' interests and school resources and important refinements to notions of

'conformity' and 'deviance'. The investigation of key words, as discussed in Section 5.1, is another

common method for unpacking meanings.

CATEGORY AND CONCEPT FO UNDAT ION

There comes a time when the mass of data embodied in field-notes, transcripts, documents, has to

be ordered in some kind of systematic way, usually by classifying and categorizing. At an elementary

level, this simply applies to the data one has. There may be no concept formation, importation or

-

6 2 -

discovery of theory, creation of new thoughts at this stage. The object is to render one's material in a form

conducive to those pursuits. This means ordering data in some kind of integrated, exhaustive, logical,

succinct way.

The first step is to identify the major categories, which, in turn, may fall into groups. The data can

then be marshalled behind these. What the categories are depends on the kind of study and one's interests.

They may be to do with perspectives on a particular issue, certain activities or events, relationships

between people, situations and contexts, behaviours and so forth.

The test of the appropriateness of such a scheme is to see whether most of the material can be

firmly accommodated within one of the categories and, as far as is possible, within one category alone.

Also, the categories should be at the same level of analysis, as should any subcategories. One usually has

to have several shots at this before coming to the most appropriate arrangement, reading and rereading

notes and transcripts and experimenting with a number of formulations. It may be helpful to summarize

data, tabulate them on a chart, or construct figures and diagrams. Such distillation helps one to

encapsulate more of the material in a glance as it were and thus aids the formulation of categories.

The following are some fairly typical examples of categorization.

Example 1

Paul Willis (1977), 'Elements of a culture' from Learning to Labour. These were the major features

of 'the lads" culture:

•

Opposition to authority and rejection of the conformist.

•

The informal group.

•

Dossing, blagging and wagging.

•

Having a laff.

•

Boredom and excitement.

•

Sexism.

•

Racism.

Under these headings, Willis reconstructed the lads' outlook on life, using liberal portions of

transcript to build up a graphic and evocative picture. Notice that the categories include a mixture of the

lads' own terms, which alerted the researcher to major areas of activity, and Willis' own summarizing

features.

Example 2

John Beynon (1984), '"Sussing out" teachers: pupils as data gatherers'. Beynon observed a class of

boys during all their lessons in the first half-term of their first year at comprehensive school. The general

interest at first was in 'initial encounters' between boys and teachers. He became interested in 'the

strategies the boysemployed to find out about classrooms and type teachers; the specific nature of the

'knowledge' they required; and the means they employed to (in their words) 'suss-out' teachers' (p. 121).

He found there was a main group of boys who used a wide variety of 'sussing' strategies. One of his first

tasks, therefore, was to organize his data and identify the kinds of strategy. He found six major groups:

1.

Group formation and communication.

2.

Joking.

3.

Challenging actions (verbal).

4.

Challenges (non-verbal).

5.

Interventions.

6.

Play.

Within these, he put forward sub-groups of activities. For example:

Joking

•

Open joking.

-

6 3 -

•

Jokes based on pupils' names.

•

Risque joking.

•

Lavatorial humour.

•

Repartee and wit.

•

Set pieces.

•

Covert joking.

•

'Backchat' and 'lip'.

•

Closed joking.

•

Michelle: a private joke.

This, then, shows an organization of data using categories and subcategories, each being

graphically described by classroom observations, notes and recorded dialogue and interaction. The effect

is to re-create 'what it was like' for these pupils and their teachers and to show the considerable depth and

range of their 'sussing' activities.

Example 3

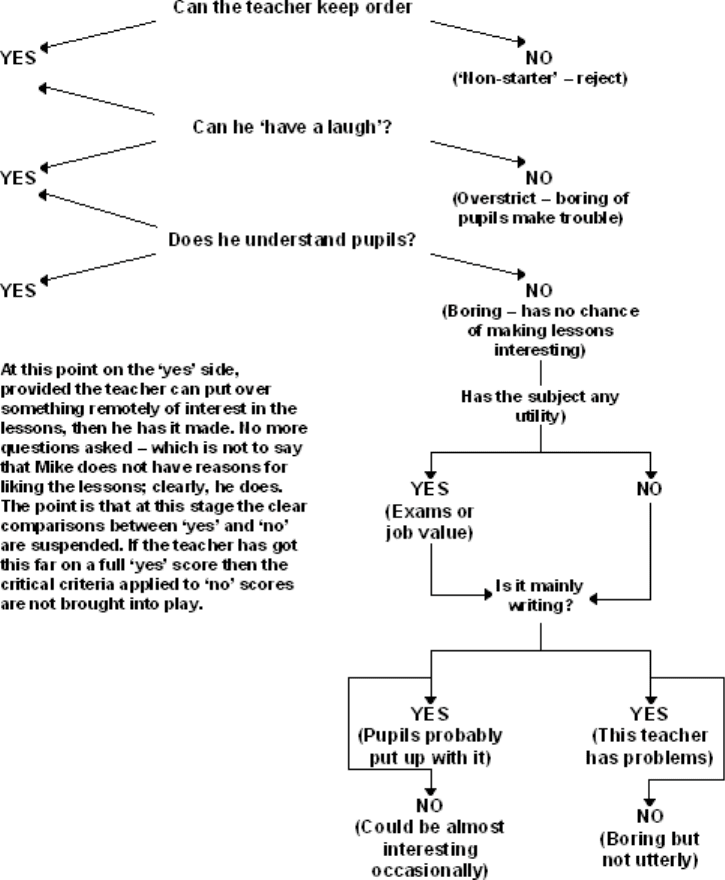

Howard Gannaway (1976) 'Making sense of school'. One of the questions raised in the

construction of categories is the interconnections between them. There had been a number of studies of

pupils' views of teachers which simply identified certain prominent features. Gannaway was concerned to

identify priorities and interrelationships among his categories. He summarized his conclusions in Figure 3

(overleaf).

THE GENERATION OF T HEORY

Some qualitative studies do not proceed beyond the construction of models and typologies. Even

so, this is a useful exercise, since it ensures that notions like 'sussing-out' have substance and delineates

their major forms. We should want to go on from there, however, if we had the time and resources, to

consider why 'sussing-out' occurs and why it takes this particular form. The research becomes more

theoretical as it moves from 'how' to 'why' questions. To answer these questions we should need to

consider three things.

Firstly, we need to seek to understand events from the point of view of the participants and try to

discover the pupils' intentions. The second factor is incidence. One would want to know when and where

this kind of activity took place and with whom. Is it limited to initial encounters between teachers and

pupils? If it is occurring at other times, another explanation is required. Under what sort of circumstances

does it occur, with what kinds of teachers and what kinds of pupils? Are all pupils involved, or only

some? What proportion of the pupils' behaviour is taken up with this kind of activity? This is the

contextual aspect. Comparisons need to be made with other sections of activity. Theory and methodology

interact, the emerging theory guiding the next part of the investigation. If there is similar activity

elsewhere then the theory may have to be revised, though there may be another explanation for that

activity.

Thirdly, what are the consequences of sussing-out? The theory would lead us to expect that where

the required knowledge was ascertained, where teachers justified their claims to being able to teach and to

control, different, more 'settled' behaviour would ensue. Where it was not, the behaviour would

presumably continue and perhaps intensify since the boundaries of tolerance would be being seen as lying

further and further back. If this is not the case, again the theory may have to be revised.

It is also necessary to explore alternative theories. In the case of 'sussing-out' one would need to

consider the possibility that the behaviour was a cultural product (e.g. of male, working-class or ethnic

culture) or an institutional product (i.e. a function of a particular kind of school organization). Some of

these, of course, may also be involved: that is, the behaviour may be and probably is multifunctional.

Comparative analysis

The development of the theory proceeds typically through comparative analysis. Instances are

compared across a range of situations, over a period of time, among a number of people and through a

variety of methods. Attention to sampling is important if the theory being formulated concerns a

particular population. Thus comparisons are made among a representative set. Negative cases are sought

-

6 4 -

for these might perhaps invalidate the argument, or suggest contrary explanations. These comparisons

may be made both inside and outside the study. These kinds of comparisons, however, can also be used

for other purposes – establishing accurate evidence, establishing empirical generalizations, specifying a

concept (bringing out the distinctive elements or nature of the case) and verifying theory.

Figure 3. An evaluation scheme for teachers.

Theorizing begins from the first day of fieldwork with the identification of possible significant

events or words, as we have seen earlier, leading eventually to identification of categories. As categories

and concepts are suggested by the data, so they prefigure the direction of the research in a process known

as 'theoretical sampling'. This is to ensure that all categories are identified and filled or groups fully

researched. Thus Mac an Ghaill (1988) followed the identification by observation of an anti-school group,

the 'Warriors', with the collection of material from school reports and questionnaires on their attitudes to

school, which enabled him to build case histories. This is another good illustration of how theory and

methodology interrelate, leading to an 'escalation of insights' (Lacey, 1976).

To aid this process the researcher becomes steeped in the data, but at the same time employs

devices to ensure breadth and depth of vision. These include the compilation of a field diary, a running

commentary on the research with reflections on one's personal involvement; further marginal comments

on field-notes, as thoughts occur on re-reading them; comparisons and contrasts with other material;

further light cast by later discoveries; relevance to other literature; notes concerning validity and

reliability; more aides-memoire, memos and notes, committing thoughts to paper on interconnections

among the data, and some possible concepts and theories. Consulting the literature is an integral part of

-

6 5 -

theory development. It helps to stimulate ideas and to give shape to the emerging theoiy, thus providing

both commentary on, and a stimulus to, study.

Consulting colleagues, for their funds of knowledge and as academic 'sounding-boards', is also

helpful. The 'sounding-board' is an important device for helping to articulate and give shape to ideas.

What may seem to be brilliant insights to the researcher may be false promises to others. The critical

scrutiny of one's peers at this formative stage is very helpful. It may be obtained by discussion (the mere

fact of trying to articulate an idea helps give it shape), by circulating papers, by giving seminars.

Another important factor is time. The deeper the involvement, the longer the association, the

wider the field of contacts and knowledge, the more intense the reflection, the stronger the promise of

'groundedness'. As Nias remarks:

The fact that I have worked for so long on the material has enabled my ideas to

grow slowly, albeit painfully. They have emerged, separated, recombined, been

tested against one another and against those of other people, been rejected,

refined, re-shaped. I have had the opportunity to think a great deal over 15 years,

about the lives and professional biographies of primary teachers and about their

experience of teaching as work. My conclusions, though they are in the last resort

those of an outsider, are both truly 'grounded' and have had the benefit of slow

ripening in a challenging professional climate.

(Nias, 1988)

Nias reminds us that a great deal of thinking has to go into this process and that this is frequently

painful, though ultimately highly rewarding. Wrestling with mounds of accumulating material, searching

for themes and indicators that willmake some sense of it all, taking some apparently promising routes

only to find they are blind alleys, writing more and more notes and memos, re-reading notes and literature

for signs and clues, doing more fieldwork to fill in holes or in the hope of discovering some beacon of

light, presenting tentative papers that receive well-formulated and devastating criticisms – all these are

part and parcel of the generation of theory.

Grounded theory has not been without its critics. Brown, for example, has argued that Glaser and

Strauss are not clear about the nature of grounded theory, nor about the link between such theory and

data. They refer to categories and their properties and to hypotheses as 'theory'. Their examples are of a

particular kind of data – classificatory, processual – amenable to that kind of analysis, but 'some

phenomena involve much greater discontinuity in either time or space or in the level of the systems

studied' (Brown, 1973, p. 6). Greater immersion in the field is unlikely to yield useful theories here.

Equally plausible alternative explanations from elsewhere may be available, so questions of how one

decides among them (i.e. methodological issues) must be considered at an early stage. We need a balance,

therefore, between verification and exploration and formulation. Bulmer (1979) raises doubts about

Glaser and Strauss' tabula rasa view of enquiry in urging concentration, and a pure line of research, on the

matter in hand, discounting existing concepts (in case of contamination) until grounded categories have

emerged. This must be very difficult to do in well-researched areas. More characteristic is the interplay of

data and conceptualization. Also, he wonders, when should the process of category development come to

an end? Possibly the method is more suited to the generation of concepts than of testable hypotheses.

In fairness, Glaser and Strauss do acknowledge the construction of theory on existing knowledge,

where that already has claims to being well grounded. They also recognize the importance of testing.

Their complaint is about testing theory inadequately related to the material it seeks to explain. As for the

confusion over theory, the identification of categories and their properties, the emergence of concepts and

the formulation of hypotheses represent a clear and well-tried route. The fact is that many qualitative

studies do not cover all these stages. This does not mean that they are without worth. Detailed

ethnographic description and theory-testing (of reasonably grounded theories) are equally legitimate

pursuits for the qualitative researcher.

-

6 6 -

5.4. SUMMARY

In this section we have considered the various stages of analysis, from the first tentative efforts to

theory formation. Preliminary and primary analysis begins by highlighting features in field-notes or

transcripts and making brief marginal notes on important points, suggested issues, interconnections, etc. It

proceeds to more extended notes on emerging themes and possible patterns and then to more fully fledged

memos, which may be half-way to the draft of a paper or at least a section of one.

At this stage, the researcher is studying the data and seeking clues to categories, themes and

issues, looking for key words, other interesting forms of language, irregularities, strange events, and so

on. This, in turn, leads to the formation of categories and concepts. We discussed the main methods and

principles involved and considered examples of some typical attempts at forming categories and

subcategories. One study had gone further and sought to establish the relative importance of the

categories identified and their interconnections.

From here we considered the further generation of theory. This could involve the further

elaboration of categories and concepts, investigating the conditions that attend them, the context and the

consequences.

Theoretical sampling also takes place, ensuring coverage and depth in the emerging pattern.

Comparative analysis plays a large part in this process, the researcher constantly comparing within and

between cases and seeking negative cases as a rigorous test of the developing theory. In another kind of

comparison or testing there is consultation with the literature and among one's peers.

Having sufficient time for this whole process is vital, as is the recognition that it involves a great

deal of thought, frequently painful and sometimes apparently chaotic. We concluded with a review of the

strengths and weaknesses of 'grounded theorizing'.

6.

QUANTITATIVE RESEARCH

In this section we turn from qualitative to quantitative methods. As we explained earlier, the

distinction between these two sorts of approach to educational research is not clear-cut. Indeed, in

beginning our exploration of quantitative research we shall examine part of a study that is generally

regarded as qualitative in character, but which, in fact, also employs a good deal of quantitative data.

The term 'quantitative research' is subject to different definitions. For the purposes of this section

we shall proceed as if it referred to:

(a) The search for causal relationships conceptualized in terms of the

interaction of 'variables', some of which (independent variables) are seen

as the cause of other (dependent) variables.

(b) The design and use of standardized research instruments (tests, attitude

scales, questionnaires, observation schedules) to collect numerical data.

(c) The manipulation of data using statistical techniques.

Our emphasis will be very much on the forms of analysis used by quantitative researchers, rather

than on the data collection techniques they employ. Selectivity is unavoidable given the time available

and we decided that this focus would give you the best sense of the character of quantitative research. We

do need to begin, however, by outlining the main sources and types of data that quantitative researchers

use. These are constrained to a considerable degree by the requirements of quantitative analysis. Most

obviously, the data need to be in numerical form – measurements of the intensity and/or frequency of

various phenomena. Some of this type of data is readily available in the form of published or unpublished

statistics: for example, school examination results, figures for absenteeism, etc. Often, though, researchers

have to produce the data themselves. This may be done in various ways. For example, via a laboratory

experiment, in which responses to some stimulus, such as a particular method of teaching, are measured.

Here the interest might be in the effectiveness of the method in bringing about students' learning.

Alternatively, quantitative data may also come from structured questionnaires administered to relatively

large samples of respondents, say teachers or pupils. If unstructured interviews can be coded into

-

6 7 -

elements that can be counted they may also be a source of quantitative data. Another source is data

produced by an observer or a team of observers using an observational schedule, which identifies various

different sorts of action or event whose frequency is to be recorded.

Phenomena vary, of course, according to how easily and accurately they can be measured. It is

one thing to document the number of A levels obtained by each member of the sixth form in a school in a

particular year. It is quite another to document the proportion of sixth formers from working-class and

from middle-class homes. There are troublesome conceptual issues involved in identifying membership

of social classes and collecting accurate information on which to base assignment to social classes is

much more difficult than finding out how many A levels were obtained. Although we shall concentrate

primarily on techniques of analysis, the threats to validity involved in the process of collectingdata must

not be ignored. We shall have occasion to discuss them at several places in this section.

We shall look firstly at the kind of causal logic that underpins quantitative methods and then at

various ways in which numerical material can be analysed in quantitative research. We have two main

objectives in this. The first and major purpose is to put you in a position where you can read the results of

quantitative research knowledgeably and critically. This is an objective that runs from beginning to end of

the section. The second objective is to show you how relatively simple quantitative methods can be used

in school-based research. The first half of this section will serve this purpose since the major example

chosen is, indeed, relatively simple and the techniques discussed are usable by a researcher with limited

time and resources.

INTRODUCING BEACHSIDE

Early in the section we shall make extensive use of a relatively simple example of quantitative

work drawn from Stephen Ball's Beachside Comprehensive, a book whose main approach is qualitative

rather than quantitative (Ball, 1981). In his book, Ball is primarily concerned with finding out whether, or

how far, the principles of comprehensive education have been implemented at a particular school, to

which he gives the pseudonym Beachside. One of the main criticisms of the selective educational system

in Britain of the 1950s and the early 1960s was that it disadvantaged working-class children because

selection for different kinds of education occurred so early. The move to comprehensive schools was

intended, in part, to overcome this problem. In carrying out this research in the late 1970s, Ball was

particularly interested in how far it was the case that working-class and middle-class children had an

equal chance of educational success at schools like Beachside Comprehensive. We shall look at only a

very small part of his work, where he examines whether the distribution of working-class and middle-

class children to bands on their entry to the school shows signs of inequality.

Activity 8. You should now read the extract from Stephen Ball's

Beachside Comprehensive which is printed in an appendix at the end of

Part 1. As you do so, make a list of the main claims he puts forward

and of the types of evidence he presents. You do not need to go into

much detail at this point. Do not worry about statistical terminology

that you do not understand, your aim should be simply to get a general

sense of the structure of Ball's argument. This will take careful

reading, however.

In the extract Ball argues that there is evidence of bias against working-class pupils in their

allocation to bands at Beachside. He supports this by comparing the distribution of middle-class and

working-class children across Bands 1 and 2 with their scores on the NFER tests of reading

comprehension and mathematics. We shall be considering this evidence in some detail later, but first we

need to give some attention to the nature of the claim he is making.

6.1. CAUSAL THINKING

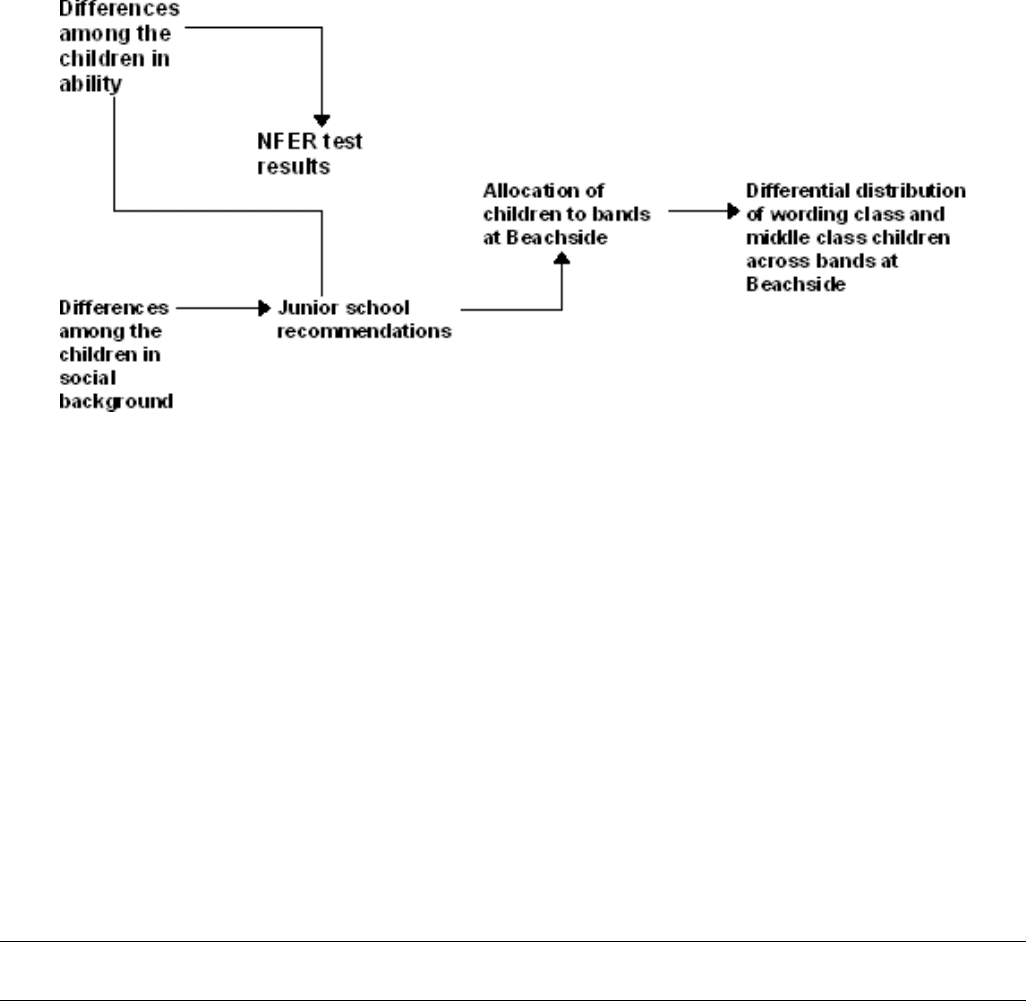

Ball's argument can be represented in the causal-network diagram shown in Figure 4.

While this causal model captures the main lines of Ball's argument, of course it represents only a

small proportion of the factors that might interact to cause pupils to be allocated to bands at Beachside.

-

6 8 -

It is worth noting that the diagram presupposes a temporal sequence in that all the arrows go one

way, from left to right. The one solid fact about causality is that something can only be caused by

something that precedes it. Thus, the left-hand side of the diagram must refer to earlier events and the

right-hand side to later events. In our case 'social class' must mean something about pupils' home

background which existed prior to their allocation to bands. Only in this sense can 'social class' be said to

have a causal relationship to allocation to bands. Of course, the causal network could be extended almost

indefinitely backwards or forwards in time.

Figure 4. A causal-network diagram of Stephen Ball’s argument.

In quantitative analysis the terms 'dependent' and 'independent' variables are frequently used. The

causes and effects identified in Figure 4 are variables. The dependent variable is the effect we are

interested in explaining and the independent variables are what are held to cause it. In Figure 4, the

allocation to bands is the dependent variable, while social class and pupil's ability (and junior teachers'

recommendations) are independent variables.

The 'time rule' for causal analysis means that changes in independent variables must occur before

the changes in the dependent variables they are held to cause. Beyond this, the way the terms are used

relates to the explanatory task at hand. Thus we could move back a step and see differences in pupils'

ability as the dependent variable, in which case differences in social background (and other things) would

be the independent variable. On the other hand, we could treat social-class differences in upbringing as

the dependent variable and look for factors that explain this, treating these as independent variables. The

meaning of the terms 'independent' and 'dependent' variables, then, derives from the explanatory task

being pursued.

Another point to notice is that we could go on adding to our independent variables, perhaps for

ever. In setting up an explanatory model, a causal network, we are selective about what we include among

the independent variables. The decision about what to include is based on the theory that we want to test.

Activity 9. What theory was Ball trying to test in the extract you

read earlier?

Ball was concerned with the extent to which the allocation of pupils to bands at Beachside was

affected independently by social class, rather than being based solely on pupils' ability. He was looking to

see if middle-class children were more likely than working-class children to be allocated to Band 1 over

and above any differences in ability. This research problem determined his selection of independent

variables: social-class background and pupils' ability.

In our diagram, we have also included the junior schools' recommendations as a factor mediating

the effects of those two other variables. The teachers from Beachside who carried out the initial allocation

to bands had no knowledge of the children other than what was available to them via the junior schools'

records and recommendations. If they had had such knowledge then we should haveneeded to include

-

6 9 -

direct causal relationships both between ability and band allocation and between social class and band

allocation.

It is worth thinking a little about the nature of Ball's hypothesis. As we indicated earlier, his

concern is with the extent to which there is inequality (or, more strictly speaking, inequity) in allocation

to bands in terms of social class. This is quite a complex issue, not least because it relies on assumptions

about what we believe to be equitable and, more generally, about what is a reasonable basis for allocation

of pupils to bands within the context of a school. It suggests that what is partly at issue in Ball's argument

is a question about the basis on which band allocation should be made, not just about how it is actually

carried out. In our discussion here, however, we shall treat Ball's hypothesis as factual; as concerned with

whether or not social class has an effect on allocation to bands over and above the effects of differences in

ability.

OPREATIONALIZATION

In order to test his hypothesis, of course, Ball had to find measures for his variables. This is

sometimes referred to as the process of 'operationalization'. Thus, in the extract you read, he is not

directly comparing the effect on band allocation of social class and the ability of children. Rather, he

compares the band allocation of children who obtained scores in the same range on the NFER tests for

reading and mathematics, whose fathers are manual and non-manual workers. He has 'operationalized'

social class in terms of the difference between households whose head has a manual as opposed to a non-

manual occupation and has 'operationalized' ability in terms of scores on NFER achievement tests. This,

obviously, raises questions about whether the variables have been measured accurately.

How well does the occupation of the head of household (categorized as manual or non-manual)

measure social class? This is by no means an uncontroversial question.

Activity 10. What potential problems can you see with this

operationalization?

There are several problems. For one thing, there are conceptual issues surrounding what we mean

by social class. Furthermore, what this operationalization typically means is that allocation of children to

social classes is based on their father's occupation. Yet, of course, many mothers have paid employment

and this may have a substantial impact on households. There has been much debate about this (see

Marshall et al, 1988). A second question that needs to be asked is whether the distinction between non-

manual and manual occupations accurately captures the difference between working class and middle

class. This too raises problems about which there has long been and continues to be much discussion. We

might also raise questions about the accuracy of the occupational information that was supplied by the

pupils and on which Ball relied.

Activity 11. Can you see any likely threats to validity in Ball's

operationalization of ability? Note down any that you can think of

before you read on.

To answer this question, we need to think about what the term 'ability' means in this context. It is

worth looking at how Ball introduces it. He appeals to the work of Ford, arguing that controlling for

measured intelligence is the most obvious way of testing for the presence of equality of opportunity. If the

impact of socialclass on educational attainment is greater than can be explained by the covariation of

social class and IQ, then the existence of equality of opportunity must be called into question, he implies.

One point that must be made in the light of this about Ball's operationalization of ability is that he

relies on achievement tests in reading and mathematics, not on the results of intelligence tests (these were

not available). We must consider what the implications of this are for the validity of the

operationalization. We need to think about what is being controlled. Effectively, Ball is asking whether

the allocations to bands were fair, as between children from different social classes, and takes a 'fair

allocation' to be one that reflects differences in intelligence. What this seems to amount to is placing those

who were more likely to benefit from being placed in Band 1 in that band and those who were more likely

to benefit from being placed in Band 2 in that band. In other words, the allocations are to be made on the

basis of predictions of likely outcomes. If this is so, it seems to us that teachers operating in this way are

-

7 0 -

unlikely to rely only on the results of achievement tests. They will use those scores, but also any other

information that is available, such as their own and other teachers' experience with the children.

Furthermore, they are likely to be interested not just in intelligence and achievement, but also in

motivation to do academic work, since that too seems likely to have an effect on future academic success.

In fact, you may remember that Ball notes that Beachside School allocated children to bands on the basis

of the primary school's recommendations and that 'test scores were not the sole basis upon which

recommendations were made. Teachers' reports were also taken into account' (see Section 2 of the

Appendix). What this indicates is that the primary schools did not regard test scores as in themselves

sufficient basis for judgments about the band into which pupils should be placed. Given this, it would not

be too surprising if Ball were to find some discrepancy between band allocation and test score, although

this discrepancy would not necessarily be related to social class.

Over and above these conceptual issues, all tests involve potential error. Ball himself notes the

problem, commenting that 'to some extent at least, findings concerning the relationships between test-

performance and social class must be regarded as an artefact of the nature of the tests employed' (see

Section 2 of the Appendix). These are not grounds for rejecting the data, but they are grounds for caution.

There are some serious questions to be raised about the operationalization of both social class and

of ability in Ball's article. For the purposes of our discussion, however, let us assume that the

measurements represented by Ball's figures are accurate and that ability is the appropriate criterion for

band allocation.

6.2. CO-VARIATION

In quantitative research the evidence used to demonstrate a causal relationship is usually 'co-

variation'. Things that vary together can usually be relied upon to be linked together in some network of

relationships between cause and effect, although the relationships may not be simple or direct.

Activity 12. Look again at Table 2.5 in the extract from Ball in the

Appendix. Does this table display co-variation between social class

(in Ball's terms) and allocations to the two forms that he studied?

The answer is that it does. We can see this just by looking at the columns labelled 'Total non-

manual' and 'Total manual'. Form 2CU contains 20 pupils from homes of non-manual workers and 12

from those of manual workers, whereas the corresponding figures for Form 2TA are 7 and 26. This

pattern is also to be found if we look at the two top bands as a whole, rather than just the individual forms

(Table 3).

Table 3. Distribution of social classes by ability bands

Band

Non-manual

Manual

Unclassified

top band

middle band

bottom band

40

29

10

54

83

20

15

19

6

Source: Table N2, p. 293 Ball (1981)

Table 4. Distribution of social classes across the second-year cohort

an Beachside 1973-74

Band

I

II

IIIn

Total non-

manual

IIIm

IV

V

Total manual

Unclassified

Band total

Band 1

Band 2

Band 3

Total

11

5

12

18

26

11

4

41

23

13

4

40

60

29

10

99

49

55

11

115

5

23

9

37

0

5

0

5

54

83

20

157

15

19

6

40

129

131

36

296

Source: Table N2, p. 293 Ball (1981)

Notice how we produced Table 3 by extracting just a small portion of the information that is

available in Ball's Table N2 (See Appendix, endnote 3). Doing so enables us to see patterns much more

clearly. At the same time, of course, it involves losing, temporarily at least, quite a lot of other