McConnell С., Campbell R. Macroeconomics: principles, problems, and policies, 17th ed

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CHAPTER 2

The Market System and the Circular Flow

33

goods and services. Money is socially defined; whatever soci-

ety accepts as a medium of exchange is money.

Most economies use pieces of paper as money.

The use of paper dollars (currency) as a medium of ex-

change is what enables Nebraska, Florida, and Idaho to

overcome their trade stalemate, as demonstrated in

Figure 2.1.

On a global basis different nations have different cur-

rencies, and that complicates specialization and exchange.

But markets in which currencies are bought and sold make

it possible for U.S. residents, Japanese, Germans, Britons,

and Mexicans, through the swapping of dollars, yen, euros,

pounds, and pesos, one for another, to exchange goods

and services.

Active, but Limited, Government

An active, but limited, government is the final characteristic

of market systems in modern advanced industrial economies.

Although a market system promotes a high degree of effi-

ciency in the use of its resources, it has certain inherent

shortcomings, called “market failures.” We will discover in

subsequent chapters that government can increase the over-

all effectiveness of the economic system in several ways.

QUICK REVIEW 2.2

• The market systems of modern industrial economies are

characterized by extensive use of technologically advanced

capital goods. Such goods help these economies achieve

greater efficiency in production.

• Specialization is extensive in market systems; it enhances

efficiency and output by enabling individuals, regions, and

nations to produce the goods and services for which their

resources are best suited.

• The use of money in market systems facilitates the exchange

of goods and services that specialization requires.

FIGURE 2.1 Money facilitates trade when wants do not coincide. The use of money as a medium of

exchange permits trade to be accomplished despite a noncoincidence of wants. (1) Nebraska trades the wheat that Florida wants for

money from Floridians; (2) Nebraska trades the money it receives from Florida for the potatoes it wants from Idaho; (3) Idaho trades

the money it receives from Nebraska for the oranges it wants from Florida.

NEBRASKA

Has surplus of

wheat.

Wants potatoes.

FLORIDA

Has surplus of

oranges.

Wants wheat.

IDAHO

Has surplus of

potatoes.

Wants oranges.

(3) Mo

n

ey

(3) Or

ang

es

(1) Mon

ey

(1) Wheat

(2) Mon

ey

(2) Potatoes

CONSIDER THIS . . .

Buy American?

Will “buying American” make

Americans better off? No, says

Dallas Federal Reserve econo-

mist W. Michael Cox:

A common myth is that it is

better for Americans to spend

their money at home than

abroad. The best way to expose

the fallacy of this argument is

to take it to its logical extreme.

If it is better for me to spend

my money here than abroad, then it is even better yet to buy

in Texas than in New York, better yet to buy in Dallas than in

Houston . . . in my own neighborhood . . . within my own

family . . . to consume only what I can produce. Alone and poor.*

*“The Fruits of Free Trade,” Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, Annual

Report 2002, p. 16.

mcc26632_ch02_028-043.indd 33mcc26632_ch02_028-043.indd 33 8/18/06 3:59:52 PM8/18/06 3:59:52 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART ONE

Introduction to Economics and the Economy

34

Five Fundamental Questions

The key features of the market system help explain how

market economies respond to five fundamental questions:

• What goods and services will be produced?

• How will the goods and services be produced?

• Who will get the goods and services?

• How will the system accommodate change?

• How will the system promote progress?

These five questions highlight the economic choices

underlying the production possibilities curve discussed in

Chapter 1. They reflect the reality of scarce resources in a

world of unlimited wants. All economies, whether market

or command, must address these five questions.

What Will Be Produced?

How will a market system decide on the specific types

and quantities of goods to be produced? The simple

answer is this: The goods and services produced at a con-

tinuing profit will be produced, and those produced at a

continuing loss will not. Profits and losses are the differ-

ence between the total revenue (TR) a firm receives from

the sale of its products and the total opportunity cost

(TC) of producing those products. (For economists,

economic costs include not only wage and salary payments

to labor, and interest and rental payments for capital and

land, but also payments to the entrepreneur for organizing

and combining the other resources to produce a

commodity.)

Continuing economic profit (TR TC) in an indus-

try results in expanded production and the movement of

resources toward that industry. Existing firms grow and

new firms enter. The industry expands. Continuing losses

(TC TR) in an industry leads to reduced production

and the exit of resources from that industry. Some existing

firms shrink in size; others go out of business. The indus-

try contracts. In the market system, consumers are sover-

eign (in command). Consumer sovereignty is crucial in

determining the types and quantities of goods produced.

Consumers spend their income on the goods they are most

willing and able to buy. Through these “dollar votes”

they register their wants in the market. If the dollar votes

for a certain product are great enough to create a profit,

businesses will produce that product and offer it for sale.

In contrast, if the dollar votes do not create sufficient rev-

enues to cover costs, businesses will not produce the prod-

uct. So the consumers are sovereign. They collectively

direct resources to industries that are meeting consumer

wants and away from industries that are not meeting con-

sumer wants.

The dollar votes of consumers determine not only

which industries will continue to exist but also which

products will survive or fail. Only profitable industries,

firms, and products survive. So firms are not as free to

produce whatever products they wish as one might other-

wise think. Consumers’ buying decisions make the pro-

duction of some products profitable and the production of

other products unprofitable, thus restricting the choice of

businesses in deciding what to produce. Businesses must

match their production choices with consumer choices or

else face losses and eventual bankruptcy.

The same holds true for resource suppliers. The em-

ployment of resources derives from the sale of the goods

and services that the resources help produce. Autoworkers

are employed because automobiles are sold. There are few

remaining professors of early Latin because there are few

McHits and

McMisses

McDonald’s has introduced

several new menu items over

the decades. Some have been

profitable “hits,” while others

have been “misses.” Ultimately,

consumers decide whether a

menu item is profitable and

therefore whether it stays on

the McDonald’s menu.

• Hulaburger (1962)—McMiss

• Filet-O-Fish (1963)—McHit

• Strawberry shortcake (1966)—McMiss

• Big Mac (1968)—McHit

• Hot apple pie (1968)—McHit

• Egg McMuffin (1975)—McHit

• Drive-thru (1975)—McHit

• Chicken McNuggets (1983)—McHit

• Extra Value Meal (1991)—McHit

• McLean Deluxe (1991)—McMiss

• Arch Deluxe (1996)—McMiss

• 55-cent special (1997)—McMiss

• Big Xtra (1999)—McHit

Source: “Polishing the Golden Arches,” Forbes, June 15, 1998, pp. 42–43,

updated.

CONSIDER THIS . . .

mcc26632_ch02_028-043.indd 34mcc26632_ch02_028-043.indd 34 8/18/06 3:59:52 PM8/18/06 3:59:52 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 2

The Market System and the Circular Flow

35

people desiring to learn the Latin language. Resource

suppliers, desiring to earn income, are not truly free to al-

locate their resources to the production of goods that con-

sumers do not value highly. Consumers register their

preferences in the market; producers and resource suppli-

ers, prompted by their own self-interest, respond appro-

priately. (Key Question 8)

How Will the Goods and Services

Be Produced?

What combinations of resources and technologies will be

used to produce goods and services? How will the produc-

tion be organized? The answer: In combinations and ways

that minimize the cost per unit of output. Because com-

petition eliminates high-cost producers, profitability re-

quires that firms produce their output at minimum cost

per unit. Achieving this least-cost production necessitates,

for example, that firms use the right mix of labor and cap-

ital, given the prices and productivity of those resources. It

also means locating production facilities optimally to hold

down production and transportation expenses.

Least-cost production also means that firms must em-

ploy the most economically efficient technique of produc-

tion in producing their output. The most efficient

production technique depends on:

• The available technology, that is, the various

combinations of resources that will produce the

desired results.

• The prices of the needed resources.

A technique that requires just a few inputs of resources to

produce a specific output may be highly inefficient eco-

nomically if those resources are valued very highly in the

market. Economic efficiency means obtaining a particular

output of product with the least input of scarce resources,

when both output and resource inputs are measured in

dollars and cents. The combination of resources that will

produce, say, $15 worth of bathroom soap at the lowest

possible cost is the most efficient.

Suppose there are three possible techniques for pro-

ducing the desired $15 worth of bars of soap. Suppose also

that the quantity of each resource required by each pro-

duction technique and the prices of the required resources

are as shown in Table 2.1. By multiplying the required

quantities of each resource by its price in each of the three

techniques, we can determine the total cost of producing

$15 worth of soap by means of each technique.

Technique 2 is economically the most efficient, be-

cause it is the least costly. It enables society

to obtain $15 worth of output by using a

smaller amount of resources—$13 worth—

than the $15 worth required by the two

other techniques. Competition will dictate

that producers use technique 2. Thus, the

question of how goods will be produced is

answered. They will be produced in a least-

cost way.

A change in either technology or resource prices,

however, may cause a firm to shift from the technology it

is using. If the price of labor falls to $.50, technique 1

becomes more desirable than technique 2. Firms will find

they can lower their costs by shifting to a technology that

uses more of the resource whose price has fallen. Exer-

cise: Would a new technique involving 1 unit of labor, 4

of land, 1 of capital, and 1 of entrepreneurial ability be

preferable to the techniques listed in Table 2.1, assuming

the resource prices shown there? (Key Question 9)

Who Will Get the Output?

The market system enters the picture in two ways when

determining the distribution of total output. Generally, any

product will be distributed to consumers on the basis of

their ability and willingness to pay its existing market price.

If the price of some product, say, a small sailboat, is $3000,

then buyers who are willing and able to pay that price will

“sail, sail away.” Consumers who are unwilling or unable to

pay the price will be “sitting on the dock of the bay.”

W 2.1

Least-cost

production

Units of Resource

Price per Unit

Technique 1 Technique 2 Technique 3

Resource of Resource Units Cost Units Cost Units Cost

Labor $2 4 $ 8 2 $ 4 1 $ 2

Land 1 1 1 3 3 4 4

Capital 3 1 3 1 3 2 6

Entrepreneurial ability 3 1 3 1 3 1 3

Total cost of $15 worth of bar soap $15 $13 $15

TABLE 2.1 Three Techniques for Producing $15 Worth of Bar Soap

mcc26632_ch02_028-043.indd 35mcc26632_ch02_028-043.indd 35 8/18/06 3:59:53 PM8/18/06 3:59:53 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART ONE

Introduction to Economics and the Economy

36

The ability to pay the prices for sailboats and other

products depends on the amount of income that consum-

ers have, along with the prices of, and preferences for,

various goods. If consumers have sufficient income and

want to spend their money on a particular good, they can

have it. And the amount of income they have depends on

(1) the quantities of the property and human resources

they supply and (2) the prices those resources command in

the resource market. Resource prices (wages, interest,

rent, profit) are crucial in determining the size of each

person’s income and therefore each person’s ability to buy

part of the economy’s output. If a lawyer earning $200 an

hour and a recreational worker earning $10 an hour both

work the same number of hours each year, the lawyer will

be able to take possession of 20 times as much of society’s

output as the recreational worker that year.

How Will the System

Accommodate Change?

Market systems are dynamic: Consumer preferences, tech-

nology, and supplies of resources all change. This means

that the particular allocation of resources that is now the

most efficient for a specific pattern of consumer tastes,

range of technological alternatives, and amount of avail-

able resources will become obsolete and inefficient as con-

sumer preferences change, new techniques of production

are discovered, and resource supplies change over time.

Can the market economy adjust to such changes?

Suppose consumer tastes change. For instance, as-

sume that consumers decide they want more fruit juice

and less milk than the economy currently provides. Those

changes in consumer tastes will be communicated to pro-

ducers through an increase in spending on fruit and a de-

cline in spending on milk. Other things equal, prices and

profits in the fruit juice industry will rise and those in the

milk industry will fall. Self-interest will induce existing

competitors to expand output and entice new competitors

to enter the prosperous fruit industry and will in time

force firms to scale down—or even exit—the depressed

milk industry.

The higher prices and greater economic profit in the

fruit-juice industry will not only induce that industry to

expand but will also give it the revenue needed to obtain

the resources essential to its growth. Higher prices and

profits will permit fruit producers to attract more re-

sources from less urgent alternative uses. The reverse oc-

curs in the milk industry, where fewer workers and other

resources are employed. These adjustments in the econ-

omy are appropriate responses to the changes in consumer

tastes. This is consumer sovereignty at work.

The market system is a gigantic communications

system. Through changes in prices and profits it commu-

nicates changes in such basic matters as consumer tastes

and elicits appropriate responses from businesses and

resource suppliers. By affecting price and profits, changes

in consumer tastes direct the expansion of some indus-

tries and the contraction of others. Those adjustments

are conveyed to the resource market. As expanding indus-

tries employ more resources and contracting industries

employ fewer; the resulting changes in resource prices

(wages and salaries, for example) and income flows guide

resources from the contracting industries to the expand-

ing industries.

This directing or guiding function of prices and prof-

its is a core element of the market system. Without such a

system, some administrative agency such as a government

planning board would have to direct businesses and re-

sources into the appropriate industries. A similar analysis

shows that the system can and does adjust to other funda-

mental changes—for example, to changes in technology

and in the prices of various resources.

How Will the System Promote

Progress?

Society desires economic growth (greater output) and

higher standards of living (greater income per person).

How does the market system promote technological im-

provements and capital accumulation, both of which con-

tribute to a higher standard of living for society?

Technological Advance The market system pro-

vides a strong incentive for technological advance and en-

ables better products and processes to supplant inferior

ones. An entrepreneur or firm that introduces a popular

new product will gain revenue and economic profit at the

expense of rivals. Firms that are highly profitable one year

may find they are in financial trouble just a few years

later.

Technological advance also includes new and im-

proved methods that reduce production or distribution

costs. By passing part of its cost reduction on to the con-

sumer through a lower product price, the firm can increase

sales and obtain economic profit at the expense of rival

firms.

Moreover, the market system promotes the rapid spread

of technological advance throughout an industry. Rival

firms must follow the lead of the most innovative firm or

else suffer immediate losses and eventual failure. In some

cases, the result is creative destruction: The creation of

new products and production methods completely destroys

mcc26632_ch02_028-043.indd 36mcc26632_ch02_028-043.indd 36 8/18/06 3:59:53 PM8/18/06 3:59:53 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 2

The Market System and the Circular Flow

37

the market positions of firms that are wedded to existing

products and older ways of doing business. Example: The

advent of compact discs largely demolished long-play vinyl

records, and MP3 and other digital technologies are now

supplanting CDs.

Capital Accumulation Most technological ad-

vances require additional capital goods. The market sys-

tem provides the resources necessary to produce those

goods through increased dollar votes for capital goods.

That is, the market system acknowledges dollar voting for

capital goods as well as for consumer goods.

But who will register votes for capital goods? Answer:

Entrepreneurs and owners of businesses. As receivers of

profit income, they often use part of that income to pur-

chase capital goods. Doing so yields even greater profit

income in the future if the technological innovation is suc-

cessful. Also, by paying interest or selling ownership

shares, the entrepreneur and firm can attract some of the

income of households as saving to increase their dollar

votes for the production of more capital goods. (Key

Question 10)

promote the public or social interest. For example, we

have seen that in a competitive environment, businesses

seek to build new and improved products to increase

profits. Those enhanced products increase society’s

well-being. Businesses also use the least costly combina-

tion of resources to produce a specific output because

doing so is in their self-interest. To act otherwise would

be to forgo profit or even to risk business failure. But, at

the same time, to use scarce resources in the least costly

way is clearly in the social interest as well. It “frees up”

resources to produce something else that society

desires.

Self-interest, awakened and guided by the competi-

tive market system, is what induces responses appropriate

to the changes in society’s wants. Businesses seeking to

make higher profits and to avoid losses, and resource sup-

pliers pursuing greater monetary rewards, negotiate

changes in the allocation of resources and end up with the

output that society wants. Competition controls or guides

self-interest such that self-interest automatically and

quite unintentionally furthers the best interest of society.

The invisible hand ensures that when firms maximize

their profits and resource suppliers maximize their in-

comes, these groups also help maximize society’s output

and income.

Of the various virtues of the market system, three

merit reemphasis:

• Efficiency The market system promotes the efficient

use of resources by guiding them into the production

of the goods and services most wanted by society. It

forces the use of the most efficient techniques in or-

ganizing resources for production, and it encourages

the development and adoption of new and more effi-

cient production techniques.

• Incentives The market system encourages skill ac-

quisition, hard work, and innovation. Greater work

skills and effort mean greater production and higher

incomes, which usually translate into a higher stan-

dard of living. Similarly, the assuming of risks by

entrepreneurs can result in substantial profit in-

comes. Successful innovations generate economic

rewards.

• Freedom The major noneconomic argument for the

market system is its emphasis on personal freedom.

In contrast to central planning, the market system

coordinates economic activity without coercion.

The market system permits—indeed, it thrives on—

freedom of enterprise and choice. Entrepreneurs and

workers are free to further their own self-interest,

subject to the rewards and penalties imposed by the

market system itself.

QUICK REVIEW 2.3

• The output mix of the market system is determined by

profits, which in turn depend heavily on consumer

preferences. Economic profits cause industries to expand;

losses cause industries to contract.

• Competition forces industries to use the least costly

production methods.

• Competitive markets reallocate resources in response to

changes in consumer tastes, technological advances, and

changes in availability of resources.

• In a market economy, consumer income and product prices

determine how output will be distributed.

• Competitive markets create incentives for technological

advance and capital accumulation, both of which contribute

to increases in standards of living.

The “Invisible Hand”

In his 1776 book The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith

first noted that the operation of a market system creates

a curious unity between private interests and social in-

terests. Firms and resource suppliers, seeking to further

their own self-interest and operating within the frame-

work of a highly competitive market system, will simul-

taneously, as though guided by an “invisible hand,”

mcc26632_ch02_028-043.indd 37mcc26632_ch02_028-043.indd 37 8/18/06 3:59:54 PM8/18/06 3:59:54 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART ONE

Introduction to Economics and the Economy

38

The Demise of the Command

Systems

Our discussion of how a market system answers the five

fundamental questions provides insights on why command

systems of the Soviet Union, eastern Europe, and China

(prior to its market reforms) failed. Those systems en-

countered two insurmountable problems.

The Coordination Problem

The first difficulty was the coordination problem. The

central planners had to coordinate the millions of individ-

ual decisions by consumers, resource suppliers, and busi-

nesses. Consider the setting up of a factory to produce

tractors. The central planners had to establish a realistic

annual production target, for example, 1000 tractors. They

then had to make available all the necessary inputs—labor,

machinery, electric power, steel, tires, glass, paint, trans-

portation—for the production and delivery of those 1000

tractors.

Because the outputs of many industries serve as inputs

to other industries, the failure of any single industry to

achieve its output target caused a chain reaction of reper-

cussions. For example, if iron mines, for want of machinery

or labor or transportation, did not supply the steel industry

with the required inputs of iron ore, the steel mills were

unable to fulfill the input needs of the many industries that

depended on steel. Those steel-using industries (such as

tractor, automobile, and transportation) were unable to ful-

fill their planned production goals. Eventually the chain

reaction spread to all firms that used steel as an input and

from there to other input buyers or final consumers.

The coordination problem became more difficult as

the economies expanded. Products and production pro-

cesses grew more sophisticated, and the number of indus-

tries requiring planning increased. Planning techniques

that worked for the simpler economy proved highly

inadequate and inefficient for the larger economy. Bottle-

necks and production stoppages became the norm, not the

exception. In trying to cope, planners further suppressed

product variety, focusing on one or two products in each

product category.

A lack of a reliable success indicator added to the co-

ordination problem in the Soviet Union and China (prior

to its market reforms). We have seen that market econo-

mies rely on profit as a success indicator. Profit depends

on consumer demand, production efficiency, and product

quality. In contrast, the major success indicator for the

command economies usually was a quantitative produc-

tion target that the central planners assigned. Production

costs, product quality, and product mix were secondary

considerations. Managers and workers often sacrificed

product quality and variety because they were being

awarded bonuses for meeting quantitative, not qualitative,

targets. If meeting production goals meant sloppy assem-

bly work and little product variety, so be it.

It was difficult at best for planners to assign quantita-

tive production targets without unintentionally producing

distortions in output. If the plan specified a production tar-

get for producing nails in terms of weight (tons of nails),

the enterprise made only large nails. But if it specified the

target as a quantity (thousands of nails), the firm made all

small nails, and lots of them! That is precisely what hap-

pened in the centrally planned economies.

The Incentive Problem

The command economies also faced an incentive prob-

lem. Central planners determined the output mix. When

they misjudged how many automobiles, shoes, shirts, and

chickens were wanted at the government-determined

prices, persistent shortages and surpluses of those prod-

ucts arose. But as long as the managers who oversaw the

production of those goods were rewarded for meeting

their assigned production goals, they had no incentive to

adjust production in response to the shortages and sur-

pluses. And there were no fluctuations in prices and prof-

itability to signal that more or less of certain products was

desired. Thus, many products were unavailable or in short

supply, while other products were overproduced and sat

for months or years in warehouses.

The command systems of the Soviet Union and China

before its market reforms also lacked entrepreneurship. Cen-

tral planning did not trigger the profit motive, nor did it re-

ward innovation and enterprise. The route for getting ahead

was through participation in the political hierarchy of the

Communist Party. Moving up the hierarchy meant better

housing, better access to health care, and the right to shop in

special stores. Meeting production targets and maneuvering

through the minefields of party politics were measures of

success in “business.” But a definition of business success

based solely on political savvy was not conducive to techno-

logical advance, which is often disruptive to existing prod-

ucts, production methods, and organizational structures.

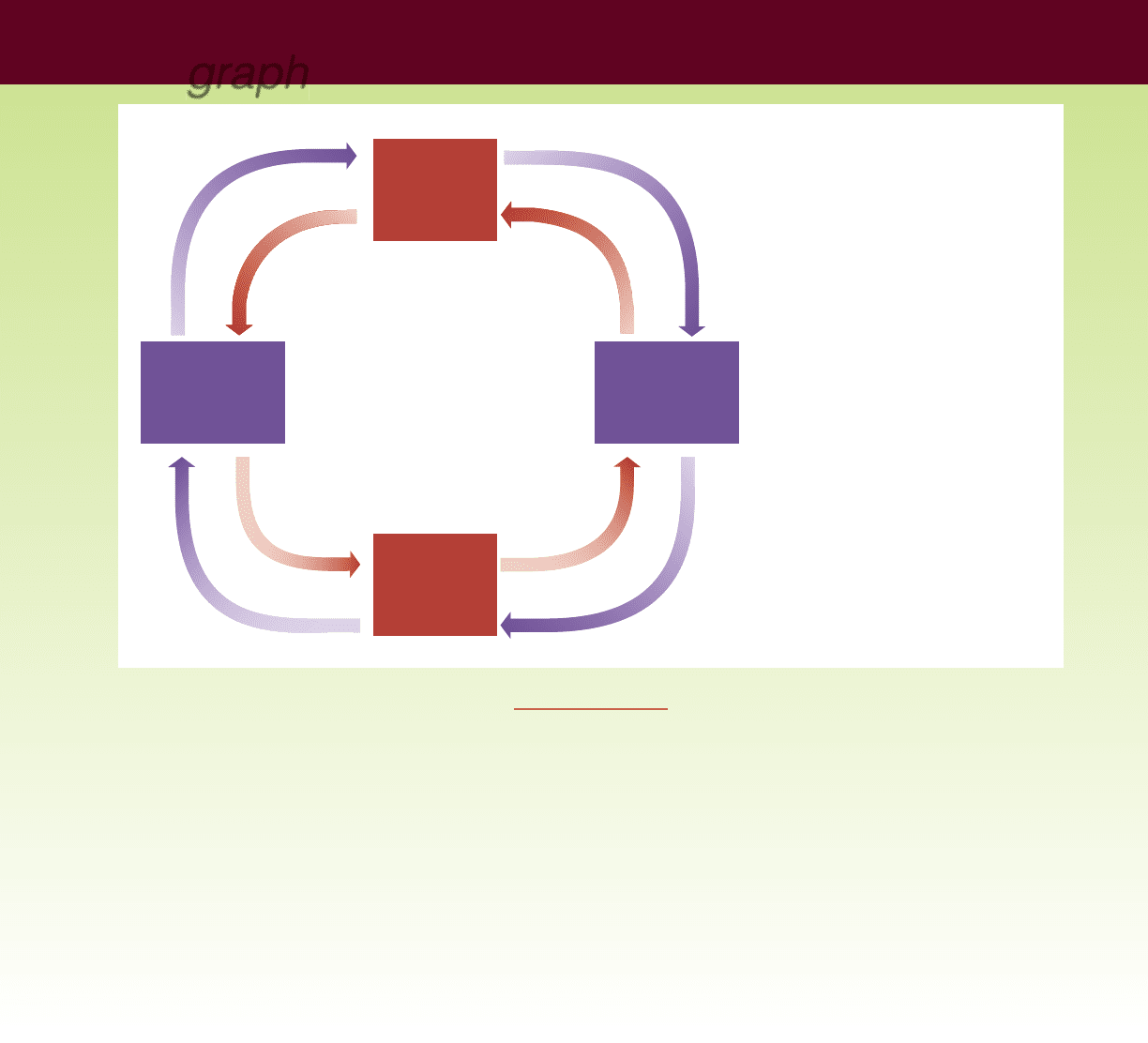

The Circular Flow

Model

The dynamic market economy creates con-

tinuous, repetitive flows of goods and ser-

vices, resources, and money. The circular

flow diagram, shown in Figure 2.2 (Key

O 2.4

Circular flow

diagram

mcc26632_ch02_028-043.indd 38mcc26632_ch02_028-043.indd 38 8/18/06 3:59:54 PM8/18/06 3:59:54 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

key

graph

QUICK QUIZ 2.2

1. The resource market is the place where:

a. households sell products and businesses buy products.

b. businesses sell resources and households sell products.

c. households sell resources and businesses buy resources (or

the services of resources).

d. businesses sell resources and households buy resources (or

the services of resources).

2. Which of the following would be determined in the product

market?

a. a manager’s salary.

b. the price of equipment used in a bottling plant.

c. the price of 80 acres of farmland.

d. the price of a new pair of athletic shoes.

3. In this circular flow diagram:

a. money flows counterclockwise.

b. resources flow counterclockwise.

c. goods and services flow clockwise.

d. households are on the selling side of the product market.

4. In this circular flow diagram:

a. households spend income in the product market.

b. firms sell resources to households.

c. households receive income through the product market.

d. households produce goods.

G

o

o

d

s

a

n

d

s

e

r

v

i

c

e

s

R

e

v

e

n

u

e

G

o

o

d

s

a

n

d

s

e

r

v

i

c

e

s

C

o

n

s

u

m

p

t

i

o

n

e

x

p

e

n

d

i

t

u

r

e

s

M

o

n

e

y

i

n

c

o

m

e

(

w

a

g

e

s

,

r

e

n

t

s

,

i

n

t

e

r

e

s

t

,

p

r

o

f

i

t

s

)

n

e

u

r

i

a

l

a

b

i

l

i

t

y

C

o

s

t

s

R

e

s

o

u

r

c

e

s

BUSINESSES HOUSEHOLDS

PRODUCT

MARKET

RESOURCE

MARKET

L

a

b

o

r

,

l

a

n

d

,

c

a

p

i

t

a

l

,

e

n

t

r

e

p

r

e

-

• Households sell

• Businesses buy

• Businesses sell

• Households buy

• buy resources

• sell products

• sell resources

• buy products

FIGURE 2.2 The circular flow

diagram. Resources flow from households to

businesses through the resource market, and

products flow from businesses to households

through the product market. Opposite these real

flows are monetary flows. Households receive

income from businesses (their costs) through the

resource market, and businesses receive revenue

from households (their expenditures) through the

product market.

Answers: 1. c; 2. d; 3. b; 4. a

Graph), illustrates those flows. Observe that in the

diagram we group private decision makers into businesses

and households and group markets into the resource market

and the product market.

Resource Market

The upper half of the circular flow diagram represents

the resource market: the place where resources or the

services of resource suppliers are bought and sold. In the

39

resource market, households sell resources and businesses

buy them. Households (that is, people) own all economic

resources either directly as workers or entrepreneurs or

indirectly through their ownership of business corpora-

tions. They sell their resources to businesses, which buy

them because they are necessary for producing goods and

services. The funds that businesses pay for resources are

costs to businesses but are flows of wage, rent, interest,

and profit income to the households. Productive resources

mcc26632_ch02_028-043.indd 39mcc26632_ch02_028-043.indd 39 8/18/06 3:59:54 PM8/18/06 3:59:54 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART ONE

Introduction to Economics and the Economy

40

Last

Word

Shuffling the Deck

Economist Donald Boudreaux Marvels at the Way

the Market System Systematically and Purposefully

Arranges the World’s Tens of Billions of Individual

Resources.

In The Future and Its Enemies, Virginia Postrel notes the aston-

ishing fact that if you thoroughly shuffle an ordinary deck of 52

playing cards, chances are practically 100 percent that the re-

sulting arrangement of cards has never before existed. Never.

Every time you shuffle a deck, you produce an arrangement of

cards that exists for the first time in history.

The arithmetic works out that way. For a very small num-

ber of items, the number of

possible arrangements is small.

Three items, for example, can

be arranged only six different

ways. But the number of possi-

ble arrangements grows very

large very quickly. The number

of different ways to arrange five

items is 120 . . . for ten items

it’s 3,628,800 . . . for fifteen

items it’s 1,307,674,368,000.

The number of different

ways to arrange 52 items is

8.066 10

67

. This is a big

number. No human can com-

prehend its enormousness. By

way of comparison, the number of possible ways to arrange a

mere 20 items is 2,432,902,008,176,640,000—a number larger

than the total number of seconds that have elapsed since the

beginning of time ten billion years ago—and this number is

Lilliputian compared to 8.066 10

67

.

What’s the significance of these facts about numbers? Con-

sider the number of different resources available in the world—

my labor, your labor, your land, oil, tungsten, cedar, coffee

beans, chickens, rivers, the Empire State Building, [Microsoft]

Windows, the wharves at Houston, the classrooms at Oxford,

the airport at Miami, and on and on and on. No one can possi-

bly count all of the different productive resources available for

our use. But we can be sure that this number is at least in the

tens of billions.

When you reflect on how incomprehensibly large is the

number of ways to arrange a deck containing a mere 52 cards,

the mind boggles at the number of different ways to arrange all

the world’s resources.

If our world were random—if resources combined together

haphazardly, as if a giant took them all into his hands and tossed

them down like so many [cards]—it’s a virtual certainty that the

resulting combination of resources would be useless. Unless this

chance arrangement were quickly rearranged according to some

productive logic, nothing worthwhile would be produced. We

would all starve to death. Because only a tiny fraction of possi-

ble arrangements serves human ends, any arrangement will be

useless if it is chosen randomly or with inadequate knowledge of

how each and every resource

might be productively com-

bined with each other.

And yet, we witness all

around us an arrangement of

resources that’s productive and

serves human goals. Today’s ar-

rangement of resources might

not be perfect, but it is vastly

superior to most of the trillions

upon trillions of other possible

arrangements.

How have we managed to

get one of the minuscule num-

ber of arrangements that works?

The answer is private property—a social institution that encour-

ages mutual accommodation.

Private property eliminates the possibility that resource

arrangements will be random, for each resource owner chooses

a course of action only if it promises rewards to the owner that

exceed the rewards promised by all other available courses.

[The result] is a breathtakingly complex and productive

arrangement of countless resources. This arrangement emerged

over time (and is still emerging) as the result of billions upon

billions of individual, daily, small decisions made by people

seeking to better employ their resources and labor in ways that

other people find helpful.

Source: Abridged from Donald J. Boudreaux, “Mutual Accommodation,”

Ideas on Liberty, May 2000, pp. 4–5. Reprinted with permission.

40

mcc26632_ch02_028-043.indd 40mcc26632_ch02_028-043.indd 40 8/18/06 3:59:55 PM8/18/06 3:59:55 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 2

The Market System and the Circular Flow

41

Summary

1. The market system and the command system are the two

broad types of economic systems used to address the econo-

mizing problem. In the market system (or capitalism), pri-

vate individuals own most resources, and markets coordinate

most economic activity. In the command system (or social-

ism or communism), government owns most resources, and

central planners coordinate most economic activity.

2. The market system is characterized by the private owner-

ship of resources, including capital, and the freedom of indi-

viduals to engage in economic activities of their choice to

advance their material well-being. Self-interest is the driv-

ing force of such an economy, and competition functions as

a regulatory or control mechanism.

3. In the market system, markets, prices, and profits organize

and make effective the many millions of individual economic

decisions that occur daily.

4. Specialization, use of advanced technology, and the extensive

use of capital goods are common features of market systems.

Functioning as a medium of exchange, money eliminates the

problems of bartering and permits easy trade and greater

specialization, both domestically and internationally.

5. Every economy faces five fundamental questions: (a) What

goods and services will be produced? (b) How will the goods

and services be produced? (c) Who will get the goods and

services? (d) How will the system accommodate change?

(e) How will the system promote progress?

6. The market system produces products whose production

and sale yield total revenue sufficient to cover total cost. It

does not produce products for which total revenue continu-

ously falls short of total cost. Competition forces firms to

use the lowest-cost production techniques.

7. Economic profit (total revenue minus total cost) indicates

that an industry is prosperous and promotes its expansion.

Losses signify that an industry is not prosperous and hasten

its contraction.

8. Consumer sovereignty means that both businesses and re-

source suppliers are subject to the wants of consumers.

Through their dollar votes, consumers decide on the com-

position of output.

9. The prices that a household receives for the resources it

supplies to the economy determine that household’s income.

This income determines the household’s claim on the econ-

omy’s output. Those who have income to spend get the

products produced in the market system.

10. By communicating changes in consumer tastes to entrepre-

neurs and resource suppliers, the market system prompts

appropriate adjustments in the allocation of the economy’s

resources. The market system also encourages technological

advance and capital accumulation, both of which raise a na-

tion’s standard of living.

11. Competition, the primary mechanism of control in the mar-

ket economy, promotes a unity of self-interest and social

interests. As directed by an invisible hand, competition har-

nesses the self-interest motives of businesses and resource

supplier to further the social interest.

12. The command systems of the Soviet Union and pre-

reform China met their demise because of coordination

difficulties under central planning and the lack of a profit

incentive. The coordination problem resulted in bottle-

necks, inefficiencies, and a focus on a limited number of

products. The incentive problem discouraged product

improvement, new product development, and entrepre-

neurship.

13. The circular flow model illustrates the flows of resources

and products from households to businesses and from busi-

nesses to households, along with the corresponding mone-

tary flows. Businesses are on the buying side of the resource

market and the selling side of the product market. House-

holds are on the selling side of the resource market and the

buying side of the product market.

therefore flow from households to businesses, and money

flows from businesses to households.

Product Market

Next consider the lower part of the diagram, which repre-

sents the product market: the place where goods and

services produced by businesses are bought and sold.

In the product market, businesses combine resources to

produce and sell goods and services. Households use the

(limited) income they have received from the sale of re-

sources to buy goods and services. The monetary flow of

consumer spending on goods and services yields sales

revenues for businesses. Businesses compare those revenues

to their costs in determining profitability and whether or

not a particular good or service should continue to be

produced.

The circular flow model depicts a complex, interre-

lated web of decision making and economic activity in-

volving businesses and households. For the economy, it

is the circle of life. Businesses and households are both

buyers and sellers. Businesses buy resources and sell

products. Households buy products and sell resources.

As shown in Figure 2.2, there is a counterclockwise real

flow of economic resources and finished goods and ser-

vices and a clockwise money flow of income and consump-

tion expenditures.

mcc26632_ch02_028-043.indd 41mcc26632_ch02_028-043.indd 41 8/18/06 3:59:55 PM8/18/06 3:59:55 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART ONE

Introduction to Economics and the Economy

42

Terms and Concepts

economic system

command system

market system

private property

freedom of enterprise

freedom of choice

self-interest

competition

market

specialization

division of labor

medium of exchange

barter

money

consumer sovereignty

dollar votes

creative destruction

“invisible hand”

circular flow diagram

resource market

product market

Study Questions

1. Contrast how a market system and a command economy try

to cope with economic scarcity.

2. How does self-interest help achieve society’s economic

goals? Why is there such a wide variety of desired goods and

services in a market system? In what way are entrepreneurs

and businesses at the helm of the economy but commanded

by consumers?

3. Why is private property, and the protection of property

rights, so critical to the success of the market system?

4. What are the advantages of using capital in the production

process? What is meant by the term “division of labor”?

What are the advantages of specialization in the use of

human and material resources? Explain why exchange is the

necessary consequence of specialization.

5. What problem does barter entail? Indicate the economic

significance of money as a medium of exchange. What is

meant by the statement “We want money only to part

with it”?

6. Evaluate and explain the following statements:

a. The market system is a profit-and-loss system.

b. Competition is the disciplinarian of the market economy.

7. In the 1990s thousands of “dot-com” companies emerged

with great fanfare to take advantage of the Internet and new

information technologies. A few, like Yahoo, eBay, and

Amazon, have generally thrived and prospered, but many

others struggled and eventually failed. Explain these varied

outcomes in terms of how the market system answers the

question “What goods and services will be produced?”

8.

KEY QUESTION With current technology, suppose a firm is

producing 400 loaves of banana bread daily. Also assume

that the least-cost combination of resources in producing

those loaves is 5 units of labor, 7 units of land, 2 units of

capital, and 1 unit of entrepreneurial ability, selling at prices

of $40, $60, $60, and $20, respectively. If the firm can sell

these 400 loaves at $2 per unit, will it continue to produce

banana bread? If this firm’s situation is typical for the other

makers of banana bread, will resources flow to or away from

this bakery good?

9.

KEY QUESTION Assume that a business firm finds that its

profit is greatest when it produces $40 worth of product A.

Suppose also that each of the three techniques shown in the

table below will produce the desired output:

a. With the resource prices shown, which technique will

the firm choose? Why? Will production using that

technique entail profit or losses? What will be the

amount of that profit or loss? Will the industry expand

or contract? When will that expansion end?

b. Assume now that a new technique, technique 4, is de-

veloped. It combines 2 units of labor, 2 of land, 6 of

capital, and 3 of entrepreneurial ability. In view of the

resource prices in the table, will the firm adopt the new

technique? Explain your answer.

c. Suppose that an increase in the labor supply causes the

price of labor to fall to $1.50 per unit, all other resource

prices remaining unchanged. Which technique will the

producer now choose? Explain.

d. “The market system causes the economy to conserve

most in the use of resources that are particularly scarce

in supply. Resources that are scarcest relative to the de-

mand for them have the highest prices. As a result, pro-

ducers use these resources as sparingly as is possible.”

Evaluate this statement. Does your answer to part c,

above, bear out this contention? Explain.

Resource Units Required

Price per

Unit of Technique Technique Technique

Resource Resource 1 2 3

Labor $3 5 2 3

Land 4 2 4 2

Capital 2 2 4 5

Entrepreneurial

ability 2 4 2 4

10. KEY QUESTION Some large hardware stores such as Home

Depot boast of carrying as many as 20,000 different prod-

ucts in each store. What motivated the producers of those

mcc26632_ch02_028-043.indd 42mcc26632_ch02_028-043.indd 42 8/18/06 3:59:56 PM8/18/06 3:59:56 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES