McConnell С., Campbell R. Macroeconomics: principles, problems, and policies, 17th ed

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CHAPTER 7

Introduction to Economic Growth and Instability

133

Unequal Burdens An increase in the unemploy-

ment rate from 5 to, say, 7 or 8 percent might be more

tolerable to society if every worker’s hours of work and

wage income were reduced proportionally. But this is not

the case. Part of the burden of unemployment is that its

cost is unequally distributed.

Table 7.3 examines unemployment rates for various

labor market groups for 2 years. The 2001 recession

pushed the 2002 unemployment rate to 5.8 percent. In

1999, the economy achieved full employment, with a

4.2 percent unemployment rate. By observing the large

variance in unemployment rates for the different groups

within each year and comparing the rates between the

2 years, we can generalize as follows:

• Occupation Workers in lower-skilled occupations

(for example, laborers) have higher unemployment

rates than workers in higher-skilled occupations (for

example, professionals). Lower-skilled workers have

more and longer spells of structural unemployment

than higher-skilled workers. They also are less likely

to be self-employed than are higher-skilled workers.

Moreover, lower-skilled workers usually bear the

brunt of recessions. Businesses generally retain most

of their higher-skilled workers, in whom they have

invested the expense of training.

• Age Teenagers have much higher unemployment

rates than adults. Teenagers have lower skill levels,

quit their jobs more frequently, are more frequently

“fired,” and have less geographic mobility than

adults. Many unemployed teenagers are new in the

labor market, searching for their first jobs. Male

African-American teenagers, in particular, have very

high unemployment rates.

• Race and ethnicity The unemployment rate for

African-Americans and Hispanics is higher than that

for whites. The causes of the higher rates include

lower rates of educational attainment, greater con-

centration in lower-skilled occupations, and

discrimination in the labor market. In general, the

unemployment rate for African-Americans is twice

that of whites.

• Gender The unemployment rates for men and

women are very similar.

• Education Less educated workers, on average, have

higher unemployment rates than workers with more

education. Less education is usually associated with

lower-skilled, less permanent jobs, more time be-

tween jobs, and jobs that are more vulnerable to cy-

clical layoff.

• Duration The number of persons unemployed for

long periods—15 weeks or more—as a percentage of

the labor force is much lower than the overall unem-

ployment rate. But that percentage rises significantly

during recessions.

Noneconomic Costs

Severe cyclical unemployment is more than an economic

malady; it is a social catastrophe. Depression means idle-

ness. And idleness means loss of skills, loss of self-respect,

plummeting morale, family disintegration, and sociopo-

litical unrest. Widespread joblessness increases poverty,

heightens racial and ethnic tensions, and reduces hope for

material advancement.

History demonstrates that severe unemployment can

lead to rapid and sometimes violent social and political

change. Witness Hitler’s ascent to power against a back-

ground of unemployment in Germany. Furthermore,

*Civilian labor-force data. In 2002 the economy was suffering the lingering

unemployment effects of the 2001 recession.

†

People age 25 or over.

Source: Economic Report of the President; Employment and Earnings; Census Bureau,

www.census.gov.

Unemployment Rate

Demographic Group 2002 1999

Overall 5.8% 4.2%

Occupation:

Managerial and professional 3.1 1.9

Operators, fabricators, and laborers 8.9 6.3

Age:

16–19 16.5 13.9

African-American, 16–19 29.8 27.9

White, 16–19 14.5 12.0

Male, 20 5.3 3.5

Female, 20 5.1 3.8

Race and ethnicity:

African-American 10.2 8.0

Hispanic 7.5 6.4

White 5.1 3.7

Gender:

Women 5.6 4.3

Men 5.9 4.2

Education:

†

Less than high school diploma 8.4 6.0

High school diploma only 5.3 3.5

College degree or more 2.9 1.8

Duration:

15 or more weeks 2.0 1.1

TABLE 7.3 Unemployment Rates by Demographic Group:

Recession (2002) and Full Employment (1999)*

mcc26632_ch07_124-145.indd 133mcc26632_ch07_124-145.indd 133 8/21/06 4:24:52 PM8/21/06 4:24:52 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART TWO

Macroeconomic Measurement and Basic Concepts

134

relatively high unemployment among some racial and eth-

nic minorities has contributed to the unrest and violence

that has periodically plagued some cities in the United

States and abroad. At the individual level, research links

increases in suicide, homicide, fatal heart attacks and

strokes, and mental illness to high unemployment.

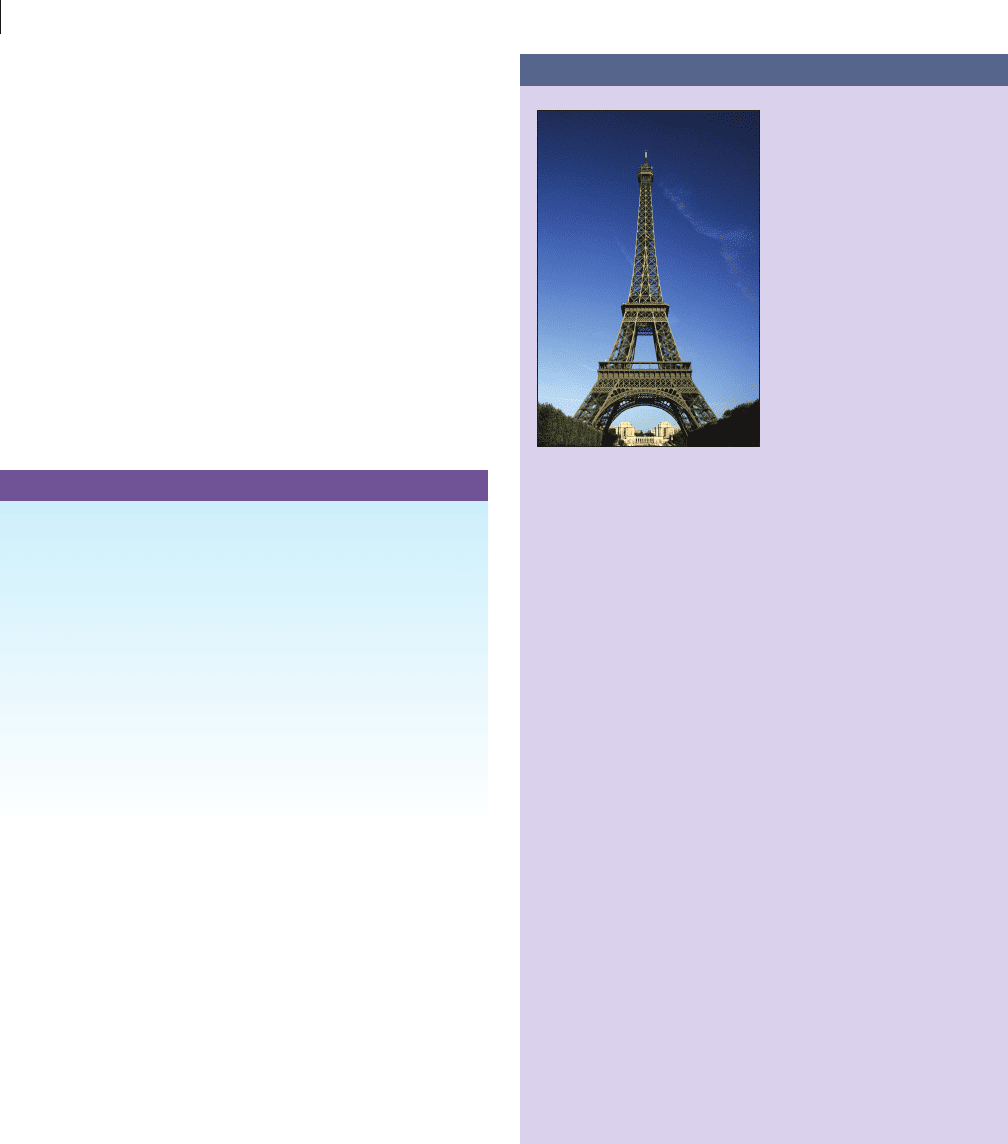

International Comparisons

Unemployment rates differ greatly among nations at any

given time. One reason is that nations have different natu-

ral rates of unemployment. Another is that nations may be

in different phases of their business cycles. Global Per-

spective 7.2 shows unemployment rates for five industrial-

ized nations in recent years. Between 1995 and 2005, the

U.S. unemployment rate was considerably lower than the

rates in Italy, France, and Germany.

QUICK REVIEW 7.2

• Unemployment is of three general types: frictional,

structural, and cyclical.

• The natural unemployment rate (frictional plus structural) is

presently 4 to 5 percent in the United States.

• A positive GDP gap occurs when actual GDP exceeds

potential GDP; a negative GDP gap occurs when actual

GDP falls short of potential GDP.

• Society loses real GDP when cyclical unemployment occurs;

according to Okun’s law, for each 1 percentage point of

unemployment above the natural rate, the U.S. economy

suffers a 2 percent decline in real GDP below its

potential GDP.

• Lower-skilled workers, teenagers, African-Americans and

Hispanics, and less educated workers bear a disproportionate

burden of unemployment.

CONSIDER THIS . . .

Why Is the

Unemp loyment

Rate in Europe So

High?

Several European economies

have had exceptionally high

unemployment rates recently.

For example, based on U.S.

measurement concepts, the

percentage unemployment

rate in 2005 in France was

9.7 percent; in Germany,

9.7 percent; in Spain, 9.6 per-

cent; and in Italy, 7.8 percent.

Those numbers compare

very unfavorably with the 5.1

percent in the United States that year. Furthermore, the high

European unemployment rates do not appear to be cyclical.

Even during business cycle peaks, the unemployment rates are

roughly twice those in the United States. Unemployment rates

are particularly high for European youth. For example, the un-

employment rate for 20- to 24-year-olds in France was 20 per-

cent in 2005 (compared to 8.8 percent in the United States).

The causes of high unemployment rates in these countries

are complex, but European economists generally point to gov-

ernment policies and union contracts that have increased the

business costs of hiring workers and have reduced the indi-

vidual cost of being unemployed. Examples: High legal minimum

wages have discouraged employers from hiring low-skilled

workers. Generous welfare benefits and unemployment bene-

fits have encouraged absenteeism, led to high job turnover, and

weakened incentives for people to take available jobs.

Restrictions on firing of workers have made firms leery of

adding workers during expansions. Short work weeks man-

dated by government or negotiated by unions have limited the

ability of employers to spread their recruitment and training

costs over a longer number of hours. Paid vacations and holi-

days of 30 to 40 days per year have boosted the cost of hiring

workers. Also, high employer costs of pension and other ben-

efits have discouraged hiring.

Attempts to make labor market more flexible in France,

Germany, Italy, and Spain have met with stiff political resis-

tance—including large rallies and protests. The direction of fu-

ture employment policy is unclear, but economists do not

expect the high rates of unemployment in these nations to

decline anytime soon.

Measurement of Inflation

The main measure of inflation in the United States is the

Consumer Price Index (CPI), compiled by the Bureau

of Labor Statistics (BLS). The government uses this index

Inflation

We now turn to inflation, another aspect of macroeco-

nomic instability. The problems inflation poses are subtler

than those posed by unemployment.

Meaning of Inflation

Inflation is a rise in the general level of prices. When in-

flation occurs, each dollar of income will buy fewer goods

and services than before. Inflation reduces the “purchas-

ing power” of money. But inflation does not mean that all

prices are rising. Even during periods of rapid inflation,

some prices may be relatively constant while others are

falling. For example, although the United States experi-

enced high rates of inflation in the 1970s and early 1980s,

the prices of video recorders, digital watches, and personal

computers declined.

mcc26632_ch07_124-145.indd 134mcc26632_ch07_124-145.indd 134 8/21/06 4:24:52 PM8/21/06 4:24:52 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 7

Introduction to Economic Growth and Instability

135

to report inflation rates each month and each year. It also

uses the CPI to adjust Social Security benefits and income

tax brackets for inflation. The CPI reports the price of a

“market basket” of some 300 consumer goods and services

that presumably are purchased by a typical urban

consumer. (The GDP price index of Chapter 6 is a much

broader measure of inflation since it includes not only

consumer goods and services but also capital goods, goods

and services purchased by government, and goods and ser-

vices that enter world trade.)

The composition of the market basket for the CPI is

based on spending patterns of urban consumers in a spe-

cific period, presently 2001–2002. The BLS updates the

composition of the market basket every 2 years so that it

reflects the most recent patterns of consumer purchases

and captures the inflation that consumers are currently ex-

periencing. The BLS arbitrarily sets the CPI equal to 100

for 1982–1984. So the CPI for any particular year is found

as follows:

price of the most recent market

CPI

basket in the particular year

_____________________________

price estimate of the same market

100

basket in 1982–1984

The rate of inflation for a certain year (say, 2005) is

found by comparing, in percentage terms, that year’s index

with the index in the previous year. For example, the CPI

was 195.3 in 2005, up from 188.9 in 2004. So the rate of

inflation for 2005 is calculated as follows:

Rate of inflation

195.3 188.9

_____________

188.9

100

3.4%

Recall that the mathematical approximation called the

rule of 70 tells us that we can find the number of years it

will take for some measure to double, given its annual

percentage increase, by dividing that percentage increase

into the number 70. So a 3 percent annual rate of inflation

will double the price level in about 23 ( 70 3) years.

Inflation of 8 percent per year will double the price level

in about 9 ( 70 8) years. (Key Question 11)

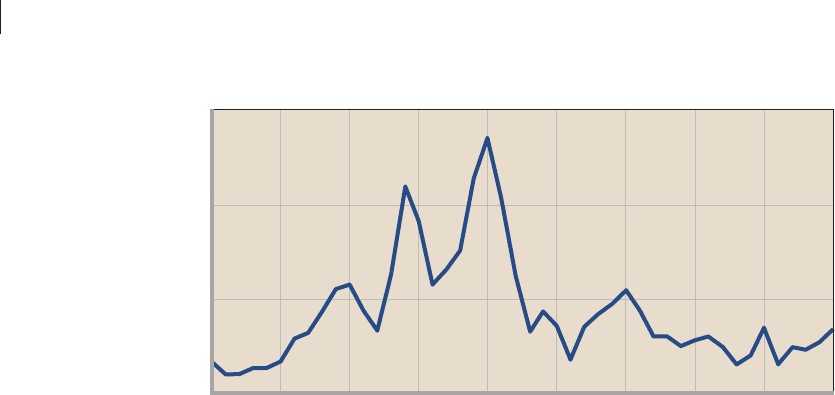

Facts of Inflation

Figure 7.4 shows the annual rates of inflation in the United

States between 1960 and 2005. Observe that inflation

reached double-digit rates in the 1970s and early 1980s but

has since declined and has been relatively mild recently.

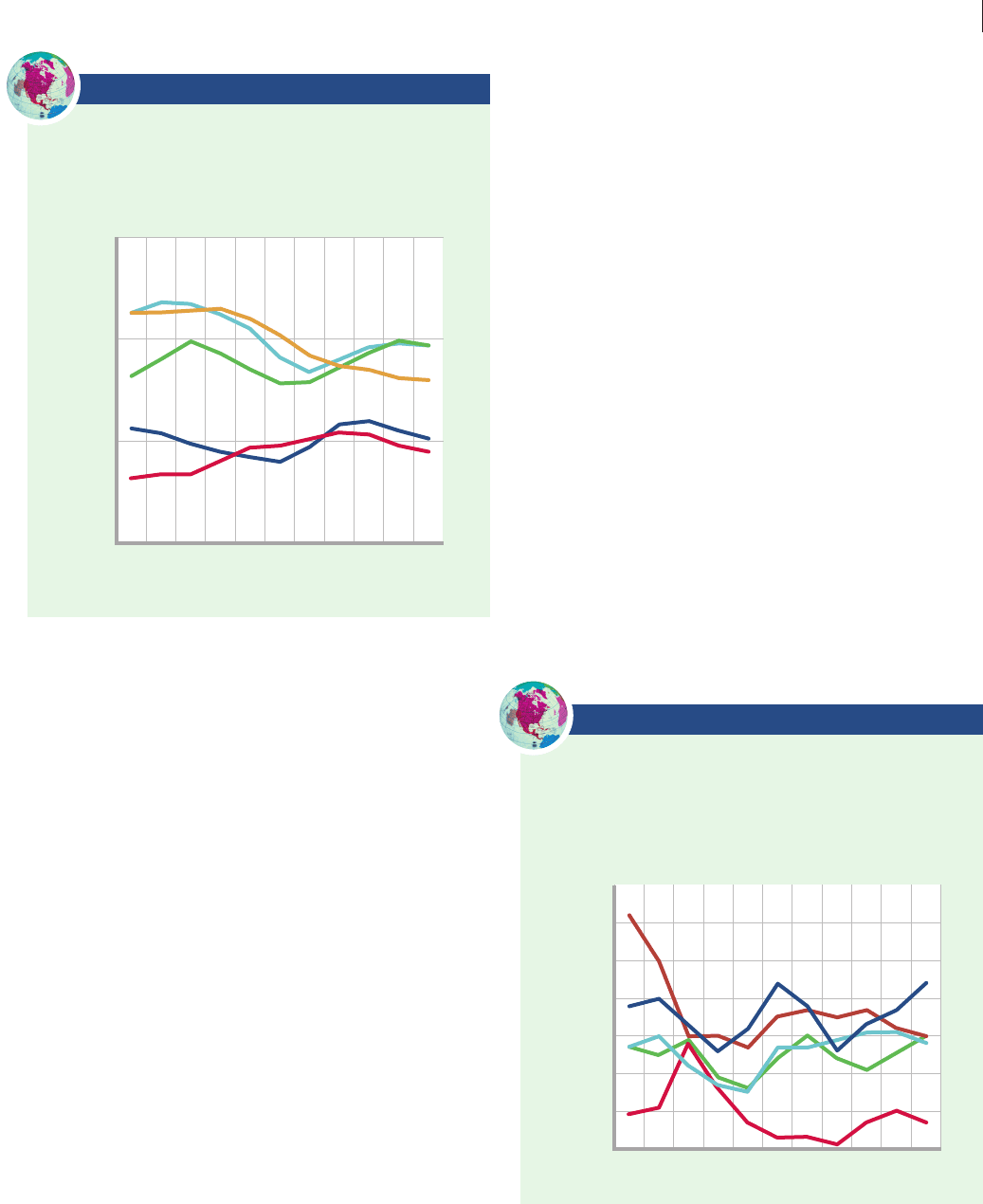

In recent years U.S. inflation has been neither unusu-

ally high nor low relative to inflation in several other in-

dustrial countries (see Global Perspective 7.3). Some

nations (not shown) have had double-digit or even higher

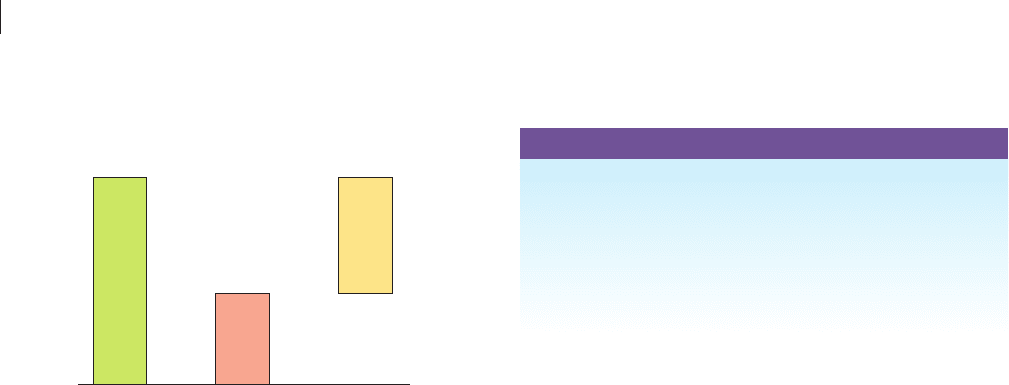

GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE 7.2

Unemployment Rates in Five Industrial Nations,

1995–2005

Compared with Italy, France, and Germany, the United States

had a relatively low unemployment rate in recent years.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, www.bls.gov. Based on

U.S. unemployment concepts.

0

5

10

15

1995 2000 2005

U.S.

Japan

France

Germany

Italy

Unemployment rate (percent)

GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE 7.3

Inflation Rates in Five Industrial Nations,

1995–2005

Inflation rates in the United States in recent years were nei-

ther extraordinarily high nor extraordinarily low relative to

rates in other industrial nations.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, www.bls.gov.

1

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

U.S.

Japan

France

Germany

Italy

1995 2000 2005

Inflation rate (percent)

mcc26632_ch07_124-145.indd 135mcc26632_ch07_124-145.indd 135 8/21/06 4:24:53 PM8/21/06 4:24:53 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART TWO

Macroeconomic Measurement and Basic Concepts

136

annual rates of inflation in recent years. In 2005, for

example, the annual inflation rate in Iraq was 40 percent;

in Liberia, 15 percent; and in Azerbaijan, 12 percent. Re-

call from the chapter opener that inflation was 585 percent

in Zimbabwe that year. For 2006, Zimbabwe’s inflation

rate is expected to reach 1000 percent!

Types of Inflation

Economists sometimes distinguish between two types of

inflation: demand-pull inflation and cost-push inflation.

Demand-Pull Inflation Usually, changes in the

price level are caused by an excess of total spending beyond

the economy’s capacity to produce. Where inflation is

rapid and sustained, the cause invariably is an overissuance

of money by the central bank (the Federal Reserve in the

United States). When resources are already fully employed,

the business sector cannot respond to excess demand by

expanding output. So the excess demand bids up the prices

of the limited output, producing demand-pull inflation.

The essence of this type of inflation is “too much spending

chasing too few goods.”

Cost-Push Inflation Inflation may also arise on

the supply, or cost, side of the economy. During some pe-

riods in U.S. economic history, including the mid-1970s,

the price level increased even though total spending was

not excessive. These were periods when output and em-

ployment were both declining (evidence that total spend-

ing was not excessive) while the general price level was

rising.

The theory of cost-push inflation explains rising

prices in terms of factors that raise per-unit production

costs at each level of spending. A per-unit production cost

is the average cost of a particular level of output. This av-

erage cost is found by dividing the total cost of all resource

inputs by the amount of output produced. That is,

Per-unit production cost

total input cost

_____________

unit of output

Rising per-unit production costs squeeze profits and

reduce the amount of output firms are willing to supply at

the existing price level. As a result, the economy’s supply

of goods and services declines and the price level rises. In

this scenario, costs are pushing the price level upward,

whereas in demand-pull inflation demand is pulling it

upward.

The major source of cost-push inflation has been

so-called supply shocks. Specifically, abrupt increases in

the costs of raw materials or energy inputs have on

occasion driven up per-unit production costs and thus

product prices. The rocketing prices of imported oil in

1973–1974 and again in 1979–1980 are good illustrations.

As energy prices surged upward during these periods,

the costs of producing and transporting virtually every

product in the economy rose. Rapid cost-push inflation

ensued.

Complexities

The real world is more complex than the distinction

between demand-pull and cost-push inflation suggests. It is

FIGURE 7.4 Annual inflation rates in the United States, 1960–2005. The major periods of

inflation in the United States in the past 40 years were in the 1970s and 1980s.

0

5

10

15

Inflation rate (percent)

2000 20051990 19951980 19851970 197519651960

Year

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, stats.bls.gov

mcc26632_ch07_124-145.indd 136mcc26632_ch07_124-145.indd 136 8/21/06 4:24:55 PM8/21/06 4:24:55 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 7

Introduction to Economic Growth and Instability

137

Without proper identification of the source of the infla-

tion, government and the Federal Reserve may be slow to

undertake policies to reduce excessive total spending.

Another complexity is that cost-push inflation and de-

mand-pull inflation differ in their sustainability. Demand-

pull inflation will continue as long as there is excess total

spending. Cost-push inflation is automatically self-limit-

ing; it will die out by itself. Increased per-unit costs will

reduce supply, and this means lower real output and em-

ployment. Those decreases will constrain further per-unit

cost increases. In other words, cost-push inflation gener-

ates a recession. And in a recession, households and busi-

nesses concentrate on keeping their resources employed,

not on pushing up the prices of those resources.

CONSIDER THIS . . .

Clipping

Coins

Some interesting

early episodes of

demand-pull in-

flation occurred

in Europe during

the ninth to the

fifteenth centu-

ries under feu-

dalism. In that economic system lords (or princes) ruled

individual fiefdoms and their vassals (or peasants) worked the

fields. The peasants initially paid parts of their harvest as taxes

to the princes. Later, when the princes began issuing “coins of

the realm,” peasants began paying their taxes with gold coins.

Some princes soon discovered a way to transfer purchasing

power from their vassals to themselves without explicitly in-

creasing taxes. As coins came into the treasury, princes clipped

off parts of the gold coins, making them slightly smaller. From

the clippings they minted new coins and used them to buy

more goods for themselves.

This practice of clipping coins was a subtle form of taxation.

The quantity of goods being produced in the fiefdom remained

the same, but the number of gold coins increased. With “too

much money chasing too few goods,” inflation occurred. Each

gold coin earned by the peasants therefore had less purchasing

power than previously because prices were higher. The in-

crease of the money supply shifted purchasing power away

from the peasants and toward the princes just as surely as if

the princes had increased taxation of the peasants.

In more recent eras some dictators have simply printed

money to buy more goods for themselves, their relatives, and

their key loyalists. These dictators, too, have levied hidden taxes

on their population by creating inflation.

The moral of the story is quite simple: A society that values

price-level stability should not entrust the control of its money

supply to people who benefit from inflation.

difficult to distinguish between demand-pull inflation and

cost-push inflation unless the original source of

inflation is known. For example, suppose a significant in-

crease in total spending occurs in a fully employed econ-

omy, causing demand-pull inflation. But as the demand-pull

stimulus works its way through various product and

resource markets, individual firms find their wage costs,

material costs, and fuel prices rising. From their perspec-

tive they must raise their prices because production costs

(someone else’s prices) have risen. Although this inflation is

clearly demand-pull in origin, it may mistakenly appear to

be cost-push inflation to business firms and to government.

QUICK REVIEW 7.3

• Inflation is a rising general level of prices and is measured as

a percentage change in a price index such as the CPI.

• For the past several years, the U.S. inflation rate has been

within the middle range of the rates of other advanced

industrial nations and far below the rates experienced by

some nations.

• Demand-pull inflation occurs when total spending exceeds

the economy’s ability to provide goods and services at the

existing price level; total spending pulls the price level

upward.

• Cost-push inflation occurs when factors such as rapid

increases in the prices of imported raw materials drive up

per-unit production costs at each level of output; higher

costs push the price level upward.

Redistribution Effects

of Inflation

Inflation hurts some people, leaves others unaffected, and

actually helps still others. That is, inflation redistributes

real income from some people to others. Who gets hurt?

Who benefits? Before we can answer, we need some

terminology.

Nominal and Real Income There is a difference

between money (or nominal) income and real income.

Nominal income is the number of dollars received as

wages, rent, interest, or profits. Real income is a measure

of the amount of goods and services nominal income can

buy; it is the purchasing power of nominal income, or in-

come adjusted for inflation. That is,

Real income

nominal income

________________________

price index (in hundredths)

mcc26632_ch07_124-145.indd 137mcc26632_ch07_124-145.indd 137 8/21/06 4:24:57 PM8/21/06 4:24:57 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART TWO

Macroeconomic Measurement and Basic Concepts

138

Inflation need not alter an economy’s overall real

income—its total purchasing power. It is evident from the

above equation that real income will remain the same

when nominal income rises at the same percentage rate as

does the price index.

But when inflation occurs, not everyone’s nominal in-

come rises at the same pace as the price level. Therein lies

the potential for redistribution of real income from some

to others. If the change in the price level differs from the

change in a person’s nominal income, his or her real

income will be affected. The following rule tells us ap-

proximately by how much real income will change:

Percentage percentage percentage

change in ⬵ change in change in

real income nominal income price level

For example, suppose that the price level rises by

6 percent in some period. If Bob’s nominal

income rises by 6 percent, his real income

will remain unchanged. But if his nominal

income instead rises by 10 percent, his real

income will increase by about 4 percent.

And if Bob’s nominal income rises by only

2 percent, his real income will decline by

about 4 percent.

1

Anticipations The redistribution effects of inflation

depend on whether or not it is expected. With fully ex-

pected or anticipated inflation, an income receiver may

be able to avoid or lessen the adverse effects of inflation on

real income. The generalizations that follow assume un-

anticipated inflation—inflation whose full extent was not

expected.

Who Is Hurt by Inflation?

Unanticipated inflation hurts fixed-income recipients, sav-

ers, and creditors. It redistributes real income away from

them and toward others.

Fixed-Income Receivers People whose incomes

are fixed see their real incomes fall when inflation occurs.

The classic case is the elderly couple living on a private

pension or annuity that provides a fixed amount of nomi-

nal income each month. They may have retired in, say,

1990 on what appeared to be an adequate pension.

However, by 2005 they would have discovered that

inflation had cut the purchasing power of that pension—

their real income—by one-third.

Similarly, landlords who receive lease payments of

fixed dollar amounts will be hurt by inflation as they re-

ceive dollars of declining value over time. Likewise, public

sector workers whose incomes are dictated by fixed pay

schedules may suffer from inflation. The fixed “steps” (the

upward yearly increases) in their pay schedules may not

keep up with inflation. Minimum-wage workers and fami-

lies living on fixed welfare incomes will also be hurt by

inflation.

Savers Unanticipated inflation hurts savers. As prices

rise, the real value, or purchasing power, of an accumula-

tion of savings deteriorates. Paper assets such as savings

accounts, insurance policies, and annuities that were once

adequate to meet rainy-day contingencies or provide for a

comfortable retirement decline in real value during infla-

tion. The simplest case is the person who hoards money

as a cash balance. A $1000 cash balance would have lost

one-half its real value between 1982 and 2005. Of course,

most forms of savings earn interest. But the value of sav-

ings will still decline if the rate of inflation exceeds the

rate of interest.

Example: A household may save $1000 in a certificate

of deposit (CD) in a commercial bank or savings and loan

association at 6 percent annual interest. But if inflation is

13 percent (as it was in 1980), the real value or purchasing

power of that $1000 will be cut to about $938 by the end

of the year. Although the saver will receive $1060 (equal to

$1000 plus $60 of interest), deflating that $1060 for

13 percent inflation means that its real value is only about

$938 ( $1060 1.13).

Creditors Unanticipated inflation harms creditors

(lenders). Suppose Chase Bank lends Bob $1000, to be

repaid in 2 years. If in that time the price level doubles,

the $1000 that Bob repays will have only half the purchas-

ing power of the $1000 he borrowed. True, if we ignore

interest charges, the same number of dollars will be repaid

as was borrowed. But because of inflation, each of those

dollars will buy only half as much as it did when the loan

was negotiated. As prices go up, the value of the dollar

goes down. So the borrower pays back less valuable dollars

than those received from the lender. The owners of Chase

Bank suffer a loss of real income.

1

A more precise calculation uses our equation for real income. In our

first illustration above, if nominal income rises by 10 percent from $100

to $110 and the price level (index) rises by 6 percent from 100 to 106,

then real income has increased as follows:

$110

_____

1.06

$103.77

The 4 percent increase in real income shown by the simple formula in

the text is a reasonable approximation of the 3.77 percent yielded by our

more precise formula.

W 7.4

Nominal and real

income

mcc26632_ch07_124-145.indd 138mcc26632_ch07_124-145.indd 138 8/21/06 4:24:57 PM8/21/06 4:24:57 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 7

Introduction to Economic Growth and Instability

139

Who Is Unaffected or Helped

by Inflation?

Some people are unaffected by inflation and others are ac-

tually helped by it. For the second group, inflation redis-

tributes real income toward them and away from others.

Flexible-Income Receivers People who have

flexible incomes may escape inflation’s harm or even benefit

from it. For example, individuals who derive their incomes

solely from Social Security are largely unaffected by infla-

tion because Social Security payments are indexed to the

CPI. Benefits automatically increase when the CPI increases,

preventing erosion of benefits from inflation. Some union

workers also get automatic cost-of-living adjustments

(COLAs) in their pay when the CPI rises, although such

increases rarely equal the full percentage rise in inflation.

Some flexible-income receivers and all borrowers are

helped by unanticipated inflation. The strong product de-

mand and labor shortages implied by rapid demand-pull

inflation may cause some nominal incomes to spurt ahead

of the price level, thereby enhancing real incomes. For

some, the 3 percent increase in nominal income that oc-

curs when inflation is 2 percent may become a 7 percent

increase when inflation is 5 percent. As an example, prop-

erty owners faced with an inflation- induced real estate

boom may be able to boost flexible rents more rapidly

than the rate of inflation. Also, some business owners may

benefit from inflation. If product prices rise faster than re-

source prices, business revenues will increase more rapidly

than costs. In those cases, the growth rate of profit in-

comes will outpace the rate of inflation.

Debtors Unanticipated inflation benefits debtors (bor-

rowers). In our earlier example, Chase Bank’s loss of real

income from inflation is Bob’s gain of real income. Debtor

Bob borrows “dear” dollars but, because of inflation, pays

back the principal and interest with “cheap” dollars whose

purchasing power has been eroded by inflation. Real in-

come is redistributed away from the owners of Chase Bank

toward borrowers such as Bob.

The Federal government, which had amassed

$7.9 trillion of public debt through 2005 has also benefited

from inflation. Historically, the Federal government regu-

larly paid off its loans by taking out new ones. Inflation

permitted the Treasury to pay off its loans with dollars of

less purchasing power than the dollars originally bor-

rowed. Nominal national income and therefore tax collec-

tions rise with inflation; the amount of public debt owed

does not. Thus, inflation reduces the real burden of the

public debt to the Federal government.

Anticipated Inflation

The redistribution effects of inflation are less severe or

are eliminated altogether if people anticipate inflation

and can adjust their nominal incomes to reflect the ex-

pected price-level rises. The prolonged inflation that

began in the late 1960s prompted many labor unions in

the 1970s to insist on labor contracts with cost-of-living

adjustment clauses.

Similarly, if inflation is anticipated, the redistribution

of income from lender to borrower may be altered. Sup-

pose a lender (perhaps a commercial bank or a savings and

loan institution) and a borrower (a household) both agree

that 5 percent is a fair rate of interest on a 1-year loan pro-

vided the price level is stable. But assume that inflation has

been occurring and is expected to be 6 percent over the

next year. If the bank lends the household $100 at 5 percent

interest, the bank will be paid back $105 at the end of the

year. But if 6 percent inflation does occur during that year,

the purchasing power of the $105 will have been reduced

to about $99. The lender will, in effect, have paid the bor-

rower $1 for the use of the lender’s money for a year.

The lender can avoid this subsidy by charging an

inflation premium—that is, by raising the interest rate by

6 percent, the amount of the anticipated inflation. By

charging 11 percent, the lender will receive back $111 at

the end of the year. Adjusted for the 6 percent inflation,

that amount will have the purchasing power of today’s

$105. The result then will be a mutually agreeable transfer

of purchasing power from borrower to lender of $5, or

5 percent, for the use of $100 for 1 year. Financial institu-

tions have also developed variable- interest-rate mortgages

to protect themselves from the adverse effects of inflation.

(Incidentally, this example points out that, rather than be-

ing a cause of inflation, high nominal interest rates are a

consequence of inflation.)

Our example reveals the difference between the real

rate of interest and the nominal rate of interest. The real

interest rate is the percentage increase in

purchasing power that the borrower pays the

lender. In our example the real interest

rate is 5 percent. The nominal interest

rate is the percentage increase in money

that the borrower pays the lender, includ-

ing that resulting from the built-in expec-

tation of inflation, if any. In equation

form:

Nominal interest rate real interest rate

inflation premium

(the expected rate of

inflation)

O 7.2

Real interest

rates

mcc26632_ch07_124-145.indd 139mcc26632_ch07_124-145.indd 139 8/21/06 4:24:58 PM8/21/06 4:24:58 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART TWO

Macroeconomic Measurement and Basic Concepts

140

As illustrated in Figure 7.5, the nominal interest rate in

our example is 11 percent.

Addenda

We end our discussion of the redistribution effects of in-

flation by making three final points:

• Deflation The effects of unanticipated deflation—

declines in the price level—are the reverse of those of

inflation. People with fixed nominal incomes will find

their real incomes enhanced. Creditors will benefit at

the expense of debtors. And savers will discover that

the purchasing power of their savings has grown be-

cause of the falling prices.

• Mixed effects A person who is an income earner, a

holder of financial assets, and an owner of real as-

sets simultaneously will probably find that the re-

distribution impact of inflation is cushioned. If the

person owns fixed-value monetary assets (savings

accounts, bonds, and insurance policies), inflation

will lessen their real value. But that same inflation

may increase the real value of any property assets

(a house, land) that the person owns. In short,

many individuals are simultaneously hurt and bene-

fited by inflation. All these effects must be consid-

ered before we can conclude that any particular

person’s net position is better or worse because of

inflation.

• Arbitrariness The redistribution effects of inflation

occur regardless of society’s goals and values. Inflation

lacks a social conscience and takes from some and

Nominal

interest

rate

11%

Real

interest

rate

5%

Inflation

premium

6%

FIGURE 7.5 The inflation premium and

nominal and real interest rates. The inflation

premium—the expected rate of inflation—gets built into

the nominal interest rate. Here, the nominal interest rate

of 11 percent comprises the real interest rate of 5 percent

plus the inflation premium of 6 percent.

QUICK REVIEW 7.4

• Inflation harms those who receive relatively fixed nominal

incomes and either leaves unaffected or helps those who

receive flexible nominal incomes.

• Unanticipated inflation hurts savers and creditors while

benefiting debtors.

• The nominal interest rate equals the real interest rate plus

the inflation premium (the expected rate of inflation).

Does Inflation Affect Output?

Thus far, our discussion has focused on how inflation re-

distributes a given level of total real income. But inflation

may also affect an economy’s level of real output (and thus

its level of real income). The direction and significance of

this effect on output depends on the type of inflation and

its severity.

Cost-Push Inflation and

Real Output

Recall that abrupt and unexpected rises in key resource

prices such as oil can sufficiently drive up overall produc-

tion costs to cause cost-push inflation. As prices rise, the

quantity of goods and services demanded falls. So firms

respond by producing less output, and unemployment

goes up.

Economic events of the 1970s provide an example of

how inflation can reduce real output. In late 1973 the Or-

ganization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), by

exerting its market power, managed to quadruple the price

of oil. The cost-push inflationary effects generated rapid

price-level increases in the 1973–1975 period. At the same

time, the U.S. unemployment rate rose from slightly less

than 5 percent in 1973 to 8.5 percent in 1975. Similar out-

comes occurred in 1979–1980 in response to a second

OPEC oil supply shock.

In short, cost-push inflation reduces real output. It re-

distributes a decreased level of real income.

Demand-Pull Inflation and

Real Output

Economists do not fully agree on the effects of mild infla-

tion (less than 3 percent) on real output. One perspective

is that even low levels of inflation reduce real output,

gives to others, whether they are rich, poor, young,

old, healthy, or infirm.

mcc26632_ch07_124-145.indd 140mcc26632_ch07_124-145.indd 140 8/21/06 4:24:58 PM8/21/06 4:24:58 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 7

Introduction to Economic Growth and Instability

141

because inflation diverts time and effort toward activities

designed to hedge against inflation. Examples:

• Businesses must incur the cost of changing thousands

of prices on their shelves and in their computers

simply to reflect inflation.

• Households and businesses must spend consider-

able time and effort obtaining the information

they need to distinguish between real and nom-

inal values such as prices, wages, and interest

rates.

• To limit the loss of purchasing power from infla-

tion, people try to limit the amount of money they

hold in their billfolds and checking accounts at any

one time and instead put more money into interest-

bearing accounts and stock and bond funds. But

cash and checks are needed in even greater amounts

to buy the higher-priced goods and services. So

more frequent trips, phone calls, or Internet visits

to financial institutions are required to transfer

funds to checking accounts and billfolds, when

needed.

Without inflation, these uses of resources, time, and effort

would not be needed, and they could be diverted toward

producing more valuable goods and services. Proponents

of “zero inflation” bolster their case by pointing to cross-

country studies that indicate that lower rates of inflation

are associated with higher rates of economic growth. Even

mild inflation, say these economists, is detrimental to

economic growth.

In contrast, other economists point out that full

employment and economic growth depend on strong

levels of total spending. Such spending creates high prof-

its, strong demand for labor, and a powerful incentive for

firms to expand their plants and equipment. In this view,

the mild inflation that is a by-product of strong spending

is a small price to pay for full employment and continued

economic growth. Moreover, a little inflation may have

positive effects because it makes it easier for firms to ad-

just real wages downward when the demands for their

products fall. With mild inflation, firms can reduce real

wages by holding nominal wages steady. With zero infla-

tion firms would need to cut nominal wages to reduce

real wages. Such cuts in nominal wages are highly visible

and may cause considerable worker resistance and labor

strife.

Finally, defenders of mild inflation say that it is much

better for an economy to err on the side of strong spend-

ing, full employment, economic growth, and mild infla-

tion than on the side of weak spending, unemployment,

recession, and deflation.

Hyperinflation

All economists agree that hyperinflation, which is

extraordinarily rapid inflation, can have a devastating im-

pact on real output and employment.

As prices shoot up sharply and unevenly during hy-

perinflation, people begin to anticipate even more rapid

inflation and normal economic relationships are disrupted.

Business owners do not know what to charge for their

products. Consumers do not know what to pay. Resource

suppliers want to be paid with actual output, rather than

with rapidly depreciating money. Creditors avoid debtors

to keep them from repaying their debts with cheap money.

Money eventually becomes almost worthless and ceases to

do its job as a medium of exchange. Businesses, anticipat-

ing further price increases, may find that hoarding both

materials and finished products is profitable. Individual

savers may decide to buy nonproductive wealth—jewels,

gold, and other precious metals, real estate, and so forth—

rather than providing funds that can be borrowed to pur-

chase capital equipment. The economy may be thrown

into a state of barter, and production and exchange drop

further. The net result is economic collapse and, often,

political chaos.

Examples of hyperinflation are Germany after the First

World War and Japan after the Second World War. In

Germany, “prices increased so rapidly that waiters changed

the prices on the menu several times during the course of a

lunch. Sometimes customers had to pay double the price

listed on the menu when they ordered.”

2

In postwar Japan,

in 1947 “fisherman and farmers . . . used scales to weigh

currency and change, rather than bothering to count it.”

3

There are also more recent examples: Between June

1986 and March 1991 the cumulative inflation in Nicara-

gua was 11,895,866,143 percent. From November 1993 to

December 1994 the cumulative inflation rate in the Dem-

ocratic Republic of Congo was 69,502 percent. From

February 1993 to January 1994 the cumulative inflation

rate in Serbia was 156,312,790 percent.

4

Such dramatic hyperinflations are almost invariably

the consequence of highly imprudent expansions of the

money supply by government. The rocketing money sup-

ply produces frenzied total spending and severe demand-

pull inflation.

2

Theodore Morgan, Income and Employment, 2nd ed. (Englewood Cliffs,

N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1952), p. 361.

3

Raburn M. Williams, Inflation! Money, Jobs, and Politicians (Arlington

Heights, Ill.: AHM Publishing, 1980), p. 2.

4

Stanley Fischer, Ratna Sahay, and Carlos Végh, “Modern Hyper- and

High Inflations,” Journal of Economic Literature, September 2002, p. 840.

mcc26632_ch07_124-145.indd 141mcc26632_ch07_124-145.indd 141 8/21/06 4:24:58 PM8/21/06 4:24:58 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART TWO

Macroeconomic Measurement and Basic Concepts

142

Last

Word

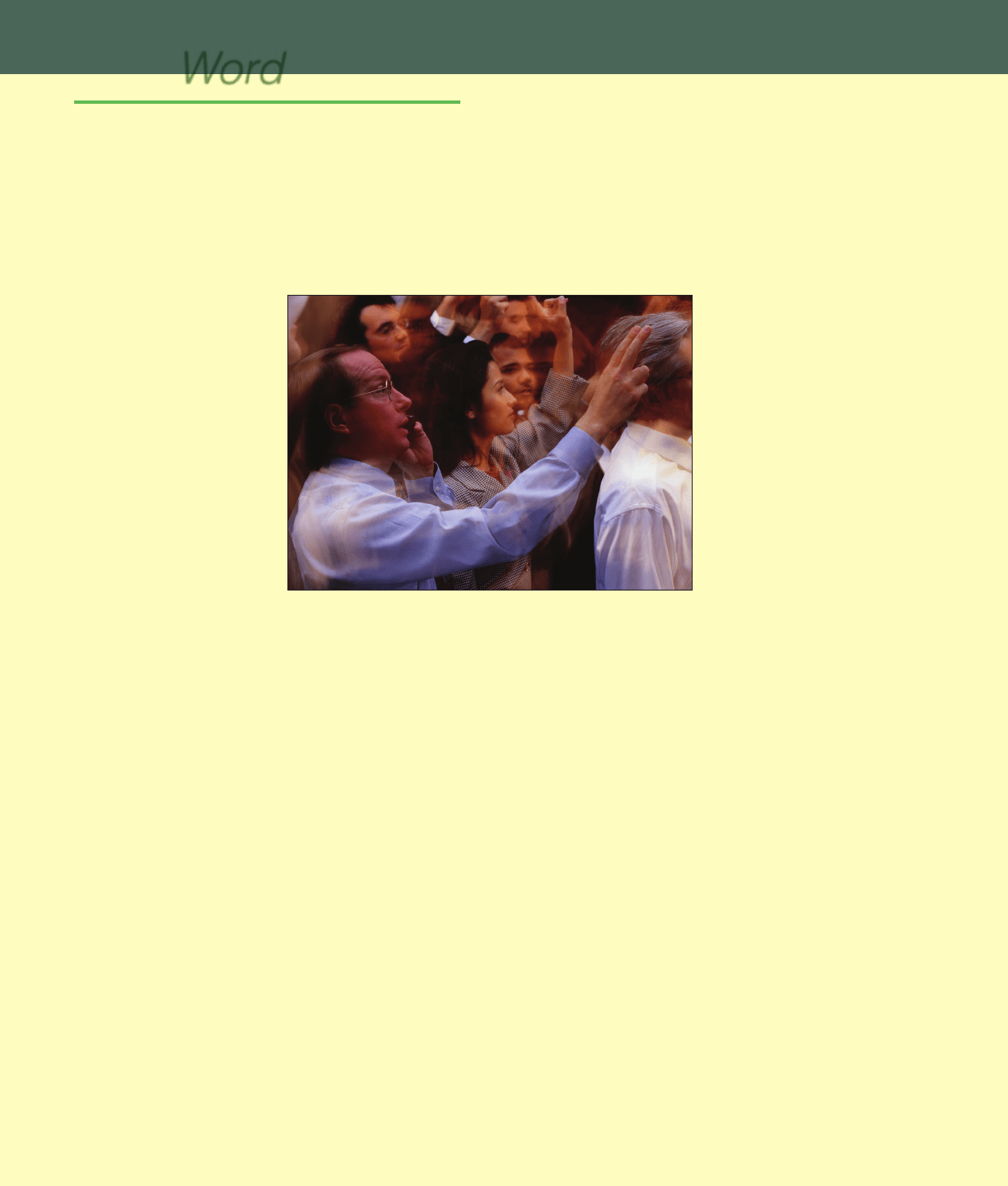

The Stock Market and the Economy

How, If at All, Do Changes in Stock Prices Relate to

Macroeconomic Instability?

Every day, the individual stocks (ownership shares) of thousands

of corporations are bought and sold in the stock market. The

owners of the individual stocks receive dividends—a portion of

the firm’s profit. Supply and

demand in the stock market

determine the price of each

firm’s stock, with individual

stock prices generally rising and

falling in concert with the

collective expectations for each

firm’s profits. Greater profits

normally result in higher divi-

dends to the stock owners, and,

in anticipation of higher divi-

dends, people are willing to pay

a higher price for the stock.

The media closely monitor

and report stock market

averages such as the Dow Jones

Industrial Average (DJIA)—the

weighted-average price of the stocks of 30 major U.S. industrial

firms. It is common for these price averages to change over

time or even to rise or fall sharply during a single day. On

“Black Monday,” October 19, 1987, the DJIA fell by 20 percent.

A sharp drop in stock prices also occurred in October 1997,

mainly in response to rapid declines in stock prices in Hong

Kong and other southeast Asia stock markets. In contrast, the

stock market averages rose spectacularly in 1998 and 1999, with

the DJIA rising 16 and 25 percent in those two years. In 2002,

the DJIA fell 17 percent. In 2003, it rose by 25 percent.

The volatility of the stock market raises this question: Do

changes in stock price averages and thus stock market wealth

cause macroeconomic instability? Linkages between the stock

market and the economy might lead us to answer “yes.” Con-

sider a sharp increase in stock prices. Feeling wealthier, stock

owners respond by increasing their spending (the wealth effect).

Firms react by increasing their purchases of new capital goods,

because they can finance such purchases through issuing new

shares of high-valued stock (the investment effect). Of course,

sharp declines in stock prices would produce the opposite results.

Studies find that changes in stock prices do affect

consumption and investment but that these consumption

and investment impacts are relatively weak. For example, a

10 percent sustained increase in stock market values in 1 year is

associated with a 4 percent increase in consumption spending

over the next 3 years. The investment response is even weaker.

So typical day-to-day and year-

to-year changes in stock market

values have little impact on the

macroeconomy.

In contrast, stock market

bubbles can be detrimental to an

economy. Such bubbles are

huge run-ups of overall stock

prices, caused by excessive opti-

mism and frenzied buying. The

rising stock values are unsup-

ported by realistic prospects of

the future strength of the econ-

omy and the firms operating in

it. Rather than slowly decom-

press, such bubbles may burst

and cause harm to the economy.

The free fall of stock values, if long-lasting, causes reverse wealth

effects. The stock market crash may also create an overall pessi-

mism about the economy that undermines consumption and in-

vestment spending even further.

A related question: Even though typical changes in stock

prices do not cause recession or inflation, might they predict

such maladies? That is, since stock market values are based on

expected profits, wouldn’t we expect rapid changes in stock

price averages to forecast changes in future business conditions?

Indeed, stock prices often do fall prior to recessions and rise

prior to expansions. For this reason stock prices are among a

group of 10 variables that constitute an index of leading indica-

tors (Last Word, Chapter 11). Such an index may provide a use-

ful clue to the future direction of the economy. But taken alone,

stock market prices are not a reliable predictor of changes in

GDP. Stock prices have fallen rapidly in some instances with no

recession following. Black Monday itself did not produce a

recession during the following 2 years. In other instances,

recessions have occurred with no prior decline in stock

market prices.

142

mcc26632_ch07_124-145.indd 142mcc26632_ch07_124-145.indd 142 8/21/06 4:24:58 PM8/21/06 4:24:58 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES