McConnell Campbell R., Brue Stanley L., Barbiero Thomas P. Microeconomics. Ninth Edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

tion possibilities curves: one showing the situation where a better technique for pro-

ducing robots has been developed while the technology for producing pizzas is

unchanged, and the other illustrating an improved technology for pizzas while the

technology for producing robots remains constant.

PRESENT CHOICES AND FUTURE POSSIBILITIES

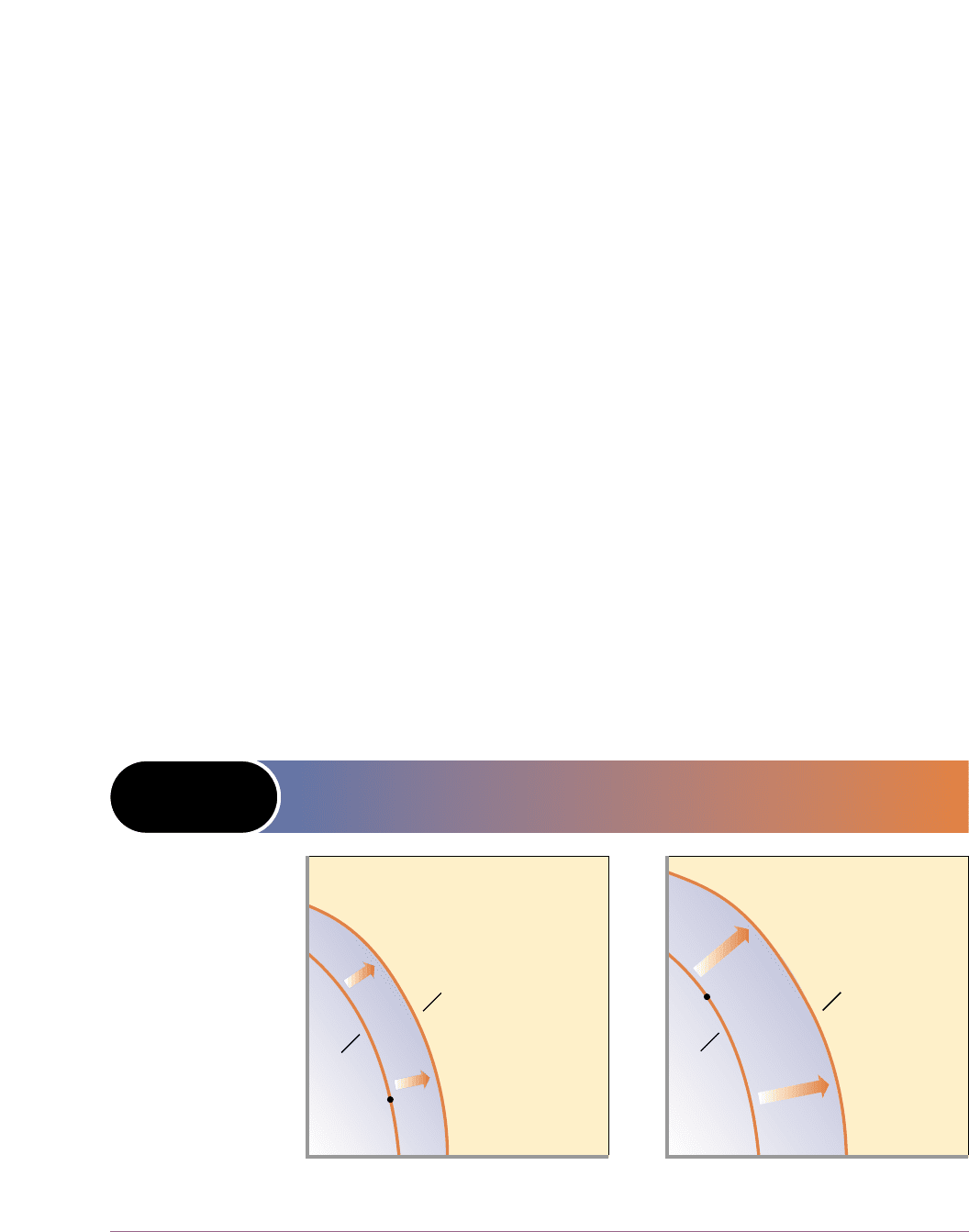

An economy’s current position on its production possibilities curve is a basic

determinant of the future location of that curve. Let’s designate the two axes of the

production possibilities curve as goods for the future and goods for the present, as in

Figure 2-5. Goods for the future are such things as capital goods, research and edu-

cation, and preventive medicine. They increase the quantity and quality of property

resources, enlarge the stock of technological information, and improve the quality

of human resources. As we have already seen, goods for the future, like industrial

robots, are the ingredients of economic growth. Goods for the present are pure con-

sumer goods, such as pizza, clothing, and soft drinks.

Now suppose there are two economies, Alta and Zorn, which are initially identi-

cal in every respect except one: Alta’s current choice of positions on its production

possibilities curve strongly favours present goods over future goods. Point A in Fig-

ure 2-5(a) indicates that choice. It is located quite far down the curve to the right,

indicating a high priority for goods for the present, at the expense of fewer goods

for the future. Zorn, in contrast, makes a current choice that stresses larger amounts

of future goods and smaller amounts of present goods, as shown by point Z in Fig-

ure 2-5(b).

Other things equal, we can expect the future production possibilities curve of

Zorn to be farther to the right than Alta’s curve. By currently choosing an output

more favourable to technological advances and to increases in the quantity and

quality of resources, Zorn will achieve greater economic growth than Alta. In terms

chapter two • the economic problem: scarcity, wants, and choices 39

FIGURE 2-5 AN ECONOMY’S PRESENT POSITION ON ITS

PRODUCTION POSSIBILITIES CURVE DETERMINES

THE CURVE’S FUTURE LOCATION

Goods for the future

Goods for the present

0

(a) Alta

Current

curve

Future

curve

Goods for the future

Goods for the present

0

(b) Zorn

Future

curve

Current

curve

A

Z

A nation’s current

choice favouring

“present goods,” as

made by Alta in (a),

will cause a modest

outward shift of the

curve in the future.

A nation’s current

choice favouring

“future goods,” as

made by Zorn in (b),

will result in a greater

outward shift of the

curve in the future.

of capital goods, Zorn is choosing to make larger current additions to its “national

factory”—to invest more of its current output—than Alta. The payoff from this

choice for Zorn is more rapid growth—greater future production capacity. The

opportunity cost is fewer consumer goods in the present for Zorn to enjoy. (See

Global Perspective 2.1.)

Is Zorn’s choice thus “better” than Alta’s? That, we cannot say. The different out-

comes simply reflect different preferences and priorities in the two countries. (Key

Question 10 and 11)

A Qualification: International Trade

Production possibilities analysis implies that a nation is limited to the combinations

of output indicated by its production possibilities curve. But we must modify this prin-

ciple when international specialization and trade exist.

You will see in later chapters that an economy can avoid, through international

specialization and trade, the output limits imposed by its domestic production pos-

sibilities curve. International specialization means directing domestic resources to out-

put that a nation is highly efficient at producing. International trade involves the

exchange of these goods for goods produced abroad. Specialization and trade

enable a nation to get more of a desired good at less sacrifice of some other good.

Rather than sacrifice three robots to get a third unit of pizza, as in Table 2-1, a nation

might be able to obtain the third unit of pizza by trading only two units of robots

for it. Specialization and trade have the same effect as having more and better

resources or discovering improved production techniques; both increase the quan-

tities of capital and consumer goods available to society.

Examples and Applications

There are many possible applications and examples relating to the production pos-

sibilities model. We will discuss just a few of them.

UNEMPLOYMENT AND PRODUCTIVE INEFFICIENCY

Almost all nations have at one point or another experienced widespread unem-

ployment of resources. That is, they have operated inside of their production pos-

sibilities curves. In the depths of the Great Depression of the 1930s, 20 percent of

Canada’s workers were unemployed and one-third of Canadian production capac-

ity was idle. In the last half of the 1990s, several countries (for example, Argentina,

Japan, Mexico, and South Korea) operated inside their production possibilities

curves, at least temporarily, because of substantial declines in economic activity.

40 Part One • An Introduction to Economics and the Economy

● Unemployment and the failure to achieve pro-

ductive efficiency cause an economy to operate

at a point inside its production possibilities curve.

● Increases in resource supplies, improvements

in resources quality, and technological advance

cause economic growth, which is depicted as an

outward shift of the production possibilities curve.

● Society’s present choice of capital and con-

sumer goods helps determine the future loca-

tion of its production possibilities curve.

● International specialization and trade enable a

nation to obtain more goods than its production

possibilities curve indicates.

Economies that experience substantial discrimination based on race, ethnicity,

and gender do not achieve productive efficiency and thus operate inside their pro-

duction possibilities curves. Because discrimination prevents those discriminated

against from obtaining jobs that best use their skills, society has less output than

otherwise. Eliminating discrimination would move such an economy from a point

inside of its production possibilities curve toward a point on its curve. Similarly,

economies in which labour usage and production methods are based on custom,

heredity, and caste, rather than on efficiency, operate well inside their production

possibilities curves.

TRADEOFFS AND OPPORTUNITY COSTS

Many current controversies illustrate the tradeoffs and opportunity costs indicated

in movements along a particular production possibilities curve. (Any two categories

of “output” can be placed on the axes of production possibilities curves.) Should

scenic land be used for logging and mining or preserved as wilderness? If the land

is used for logging and mining, the opportunity cost is the forgone benefits of

wilderness. If the land is used for wilderness, the opportunity cost is the lost value

of the wood and minerals that society forgoes.

Should society devote more resources to the criminal justice system (police,

courts, and prisons) or to education (teachers, books, and schools)? If society

devotes more resources to the criminal justice system, other things equal, the oppor-

tunity cost is forgone improvements in education. If more resources are allocated to

education, the opportunity cost is the forgone benefits from an improved criminal

justice system.

SHIFTS IN PRODUCTION POSSIBILITIES CURVES

Canada has recently experienced a spurt of new technologies relating to computers,

communications, and biotechnology. Technological advances have dropped the

prices of computers and greatly enhanced their speed. Cellular phones and the

Internet have increased communications capacity, enhancing production and

improving the efficiency of markets. Advances in biotechnology, specifically genetic

engineering, have resulted in important agricultural and medical discoveries. Many

chapter two • the economic problem: scarcity, wants, and choices 41

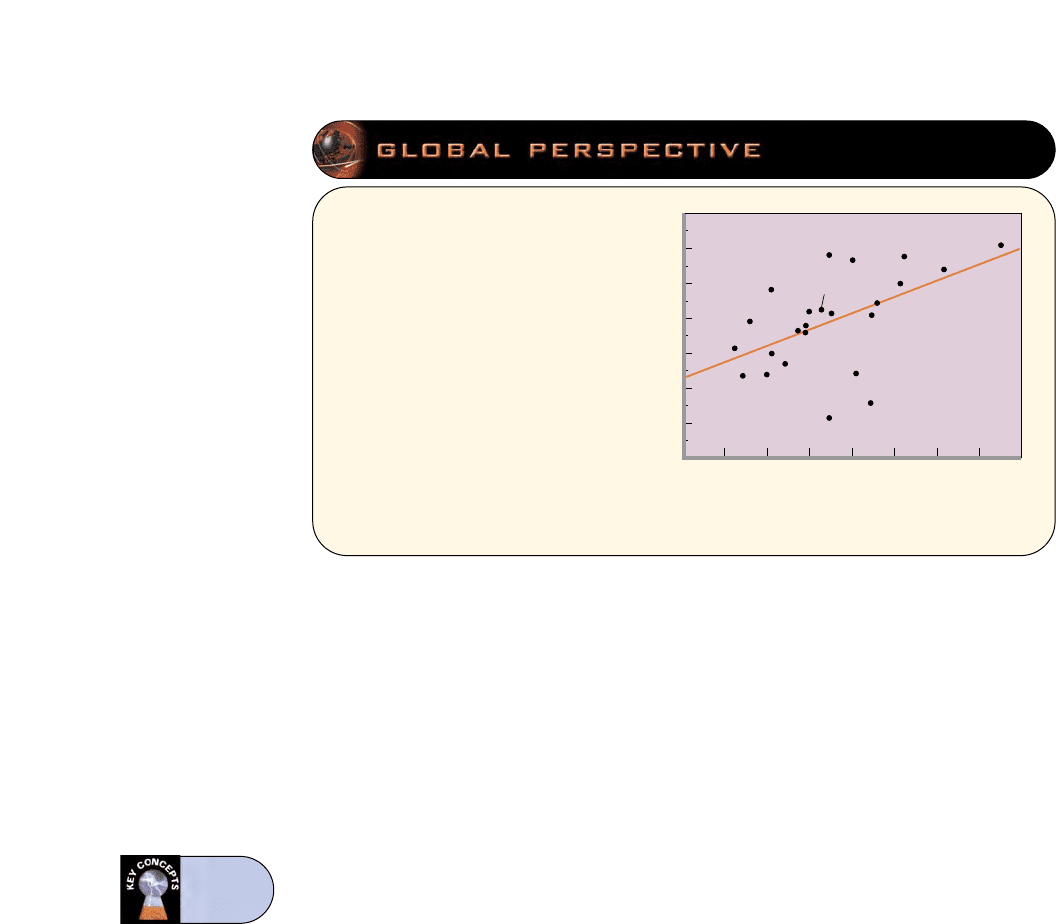

Investment and

economic growth,

selected countries

Nations that invest large por-

tions of their national output

tend to achieve high growth

rates, measured here by out-

put per person. Additional

capital goods make workers

more productive, which means

greater output per person.

2.1

4.0

U.K.

Belgium

Turkey

U.S.

Sweden

Denmark

Netherlands

France

Greece

Canada

Spain

Ireland

Iceland

Portugal

Finland

Norway

Japan

Luxembourg

Australia

Switzerland

New Zealand

Austria

Italy

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

1816 20 22 24 26 28 30 32

Annual growth rate of real

national output per person (1970–1990)

Investment as share of national output

(average, 1970–1990)

Germany

Source: International Monetary Fund

Facing

Tradeoffs

economists believe that these new technologies are so significant that they are con-

tributing to faster-than-normal economic growth (faster rightward shifts of the pro-

duction possibilities curve).

In some circumstances a nation’s production possibilities curve can collapse

inward. For example, in the late 1990s Yugoslavia forces began to “ethnically cleanse”

Kosovo by driving out its Muslim residents. A decisive military response by Canada

and its allies eventually pushed Yugoslavia out of Kosovo. The military action also

devastated Yugoslavia’s economy. Allied bombing inflicted great physical damage on

Yugoslavia’s production facilities and its system of roads, bridges, and communica-

tion. Consequently, Yugoslavia’s production possibilities curve shifted inward.

Every society needs to develop an economic system—a particular set of institutional

arrangements and a coordinating mechanism—to respond to the economic problem.

Economic systems differ as to (1) who owns the factors of production and (2) the

method used to coordinate and direct economic activity. There are two general types

of economic systems: the market system and the command system.

The Market System

The private ownership of resources and the use of markets and prices to coordinate

and direct economic activity characterize the market system, or capitalism. In that

system each participant acts in his or her own self-interest; each individual or busi-

ness seeks to maximize its satisfaction or profit through its own decisions regarding

consumption or production. The system allows for the private ownership of capi-

tal, communicates through prices, and coordinates economic activity through mar-

kets—places where buyers and sellers come together. Goods and services are

produced and resources are supplied by whoever is willing and able to do so. The

result is competition among independently acting buyers and sellers of each prod-

uct and resource. Thus, economic decision making is widely dispersed.

In pure capitalism—or laissez-faire capitalism—government’s role is limited to

protection private property and establishing an environment appropriate to the

operation of the market system. The term laissez-faire means “let it be,” that is, keep

government from interfering with the economy. The idea is that such interference

will disturb the efficient working of the market system.

But in the capitalism practised in Canada and most other countries, government

plays a substantial role in the economy. It not only provides the rules for economic

activity but also promotes economic stability and growth, provides certain goods

and services that would otherwise be underproduced or not produced at all, and

modifies the distribution of income. The government, however, is not the dominant

player in deciding what to produce, how to produce it, and who will get it. These

decisions are determined by market forces.

The Command System

The alternative to the market system is the command system, also known as social-

ism or communism. In that system, government owns most property resources and

economic decision making occurs through a central economic plan. A government

central planning board determines nearly all the major decisions concerning the use

of resources, the composition and distribution of output, and the organization of

42 Part One • An Introduction to Economics and the Economy

economic

system

A par-

ticular set of institu-

tional arrangements

and a coordinating

mechanism for

solving the econo-

mizing problem.

market

system

An

economic system

in which property

resources are pri-

vately owned and

markets and prices

are used to direct

and coordinate eco-

nomic activities.

command

system

An

economic system

in which most prop-

erty resources are

owned by the gov-

ernment and eco-

nomic decisions are

made by a central

government body.

Economic Systems

production. The government owns most of the business firms, which produce

according to government directives. A central planning board determines produc-

tion goals for each enterprise and specifies the amount of resources to be allocated

to each enterprise so that it can reach its production goals. The division of output

among the population is centrally decided, and capital goods are allocated among

industries on the basis of the central planning board’s long-term priorities.

A pure command economy would rely exclusively on a central plan to allocate the

government-owned property resources. But, in reality, even the pre-eminent com-

mand economy—the Soviet Union—tolerated some private ownership and incor-

porated some markets before its demise in 1991. Recent reforms in Russia and most

of the eastern European nations have to one degree or another transformed their

command economies to market-oriented systems. China’s reforms have not gone as

far, but have reduced the reliance on central planning. Although there is still exten-

sive government ownership of resources and capital in China, it has increasingly

relied on free markets to organize and coordinate its economy. North Korea and

Cuba are the last remaining examples of largely centrally planned economies.

Because nearly all of the major nations now use the market system, we need to gain

a good understanding of how this system operates. Our goal in the remainder of this

chapter is to identify the market economy’s decision makers and major markets. In

Chapter 3 we will explain how prices are established in individual markets. Then

in Chapter 4 we will detail the characteristics of the market system and explain how

it addresses the economic problem.

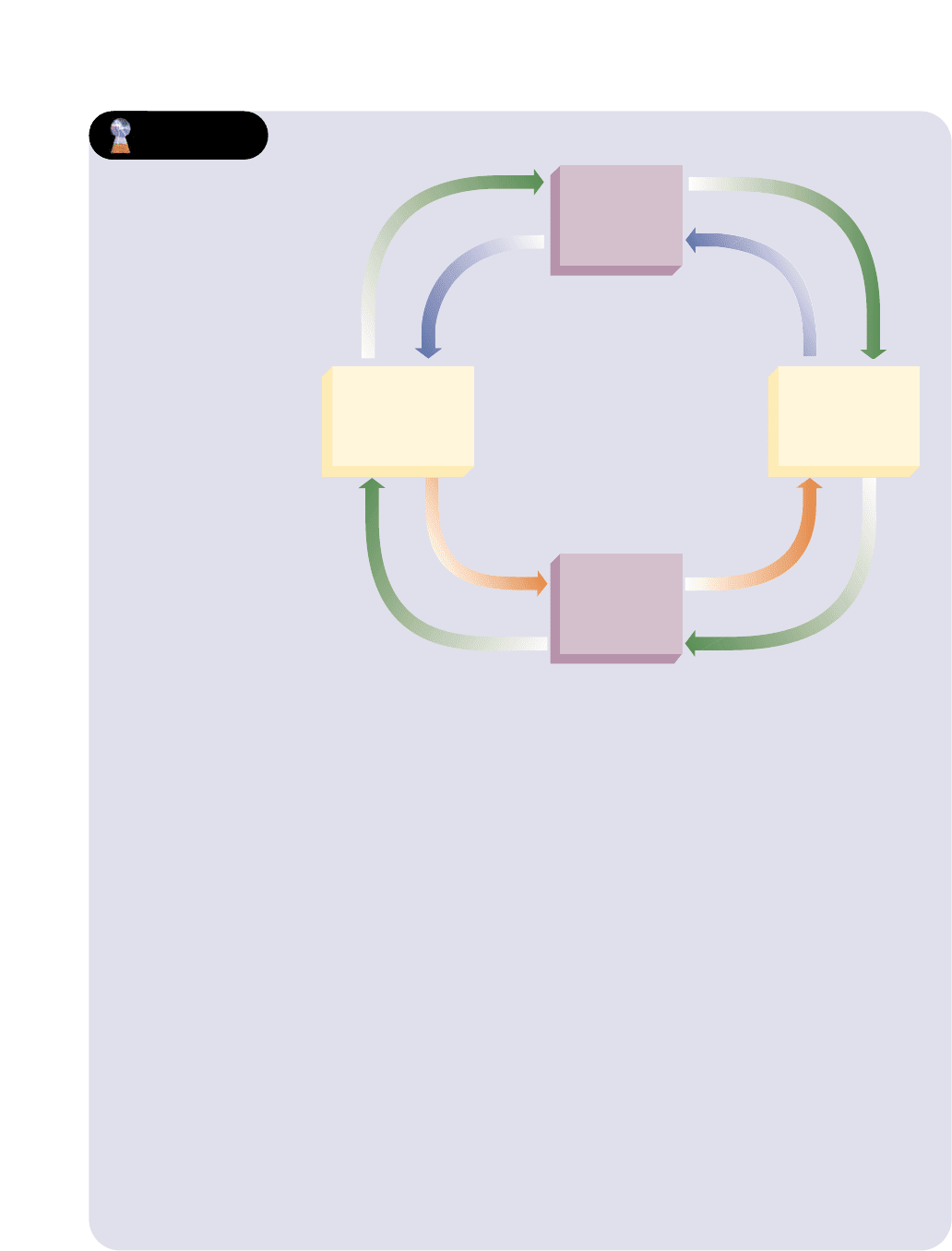

As shown in Figure 2-6 (Key Graph), the market economy has two groups of

decision makers: households and businesses. It also has two broad markets: the

resource market and the product market

The upper half of the diagram represents the resource market: the place where

resources or the services of resource suppliers are bought and sold. In the sources market,

households sell resources and businesses purchases them. Households (that is, peo-

ple) own all resources either directly as workers or entrepreneurs or indirectly

through their ownership (through stocks) of business corporations. They sell their

resources to businesses, which buy them because they are necessary for producing

goods and services. The money that businesses pay for resources are costs to busi-

nesses but are flows of wage, rent, interest, and profit income to the households.

Resources therefore flow from households to businesses, and money flows from

businesses to households.

Next consider the lower part of the diagram that represents the product market:

the place where goods and services produced by businesses are bought and sold. In the prod-

uct market, businesses combine the resources they have obtained to produce and

sell goods and services. Households use the income they have received from the sale

of resources to buy goods and services. The monetary flow of consumer spending

on goods and services yields sales revenues for businesses.

The circular flow model shows the interrelated web of decision making and eco-

nomic activity involving businesses and households. Businesses and households are

both buyers and sellers. Businesses buy resources and sell products. Households buy

products and sell resources. As shown in Figure 2-6, there is a counterclockwise real

flow of resources and finished goods and services, and a clockwise money flow of

income and consumption expenditures. These flows are simultaneous and repetitive.

chapter two • the economic problem: scarcity, wants, and choices 43

The Circular Flow Model

resource

market

A mar-

ket in which house-

holds sell and firms

buy resources or

the services of

resources.

product

market

A mar-

ket in which prod-

ucts are sold by

firms and bought

by households.

circular

flow model

The flow of

resources from

households to

firms and of prod-

ucts from firms to

households. These

flows are accompa-

nied by reverse

flows of money

from firms to

households and

from households

to firms.

44 Part One • An Introduction to Economics and the Economy

G

o

o

d

s

a

n

d

s

e

r

v

i

c

e

s

R

e

v

e

n

u

e

G

o

o

d

s

a

n

d

s

e

r

v

i

c

e

s

C

o

n

s

u

m

p

t

i

o

n

e

x

p

e

n

d

i

t

u

r

e

s

M

o

n

e

y

i

n

c

o

m

e

(

w

a

g

e

s

,

r

e

n

t

s

,

i

n

t

e

r

e

s

t

,

p

r

o

f

i

t

s

)

p

r

e

n

e

u

r

i

a

l

a

b

i

l

i

t

y

C

o

s

t

s

R

e

s

o

u

r

c

e

s

BUSINESSES HOUSEHOLDS

PRODUCT

MARKET

RESOURCE

MARKET

L

a

b

o

u

r

,

l

a

n

d

,

c

a

p

i

t

a

l

,

e

n

t

r

e

-

• Households sell

• Firms buy

• Firms sell

• Households buy

• Buy resources

• Sell products

• Sell resources

• Buy products

Resources flow from

households to businesses

through the resource mar-

ket and products flow from

businesses to household

through the product mar-

ket. Opposite these real

flows are monetary flows.

Households receive

income from businesses

(their costs) through the

resource market and busi-

nesses receive revenue

from households (their

expenditures) through the

product market.

FIGURE 2-6 THE CIRCULAR FLOW DIAGRAM

Key Graph

Quick Quiz

1. The resource market is where:

a. households sell products and businesses buy products.

b. businesses sell resources and households sell products.

c. households sell resources and businesses buy resources (or the services of

resources).

d. businesses sell resources and households buy resources (or the services of

resources).

2. Which of the following would be determined in the product market?

a. a manager’s salary

b. the price of equipment used in a bottling plant

c. the price of 80 hectares of farmland

d. the price of a new pair of athletic shoes

3. In this circular flow diagram:

a. money flows counterclockwise.

b. resources flow counterclockwise.

c. goods and services flow clockwise.

d. households are on the selling side of the product market.

4. In this circular flow diagram:

a. households spend income in the product market.

b. firms sell resources to households.

c. households receive income through the product market.

d. households produce goods.

Answers:

1. c; 2. d; 3. b; 4. a

chapter two • the economic problem: scarcity, wants, and choices 45

One of the more remarkable

trends of the past half-century in

Canada has been the substantial

rise in the number of women

working in the paid workforce.

Today, nearly 70 percent of

women work full-time or part-

time in paid jobs, compared to

only 31 percent in 1965. There are

many reasons for this increase.

Women’s Rising Wage Rates

Over recent years, women have

greatly increased their productiv-

ity in the workplace, mostly by

becoming better educated and

professionally trained. As a re-

sult, they can earn higher wages.

Because those higher wages have

increased the opportunity costs—

the forgone wage earnings—of

staying at home, women have

substituted employment in the

labour market for more “expen-

sive” traditional home activities.

This substitution has been partic-

ularly pronounced among mar-

ried women.

Women’s higher wages and

longer hours away from home

have produced creative realloca-

tions of time and purchasing

patterns. Daycare services have

partly replaced personal child

care. Restaurants, take-home

meals, and pizza delivery often

substitute for traditional home

cooking. Convenience stores

and catalogue and Internet sales

have proliferated, as have lawn-

care and in-home cleaning serv-

ices. Microwave ovens, dish-

washers, automatic washers and

dryers, and other household

“capital goods” enhance domes-

tic productivity.

Expanded Job Access Greater

access to jobs is a second factor

increasing the employment of

women. Service industries—

teaching, nursing, and clerical

work, for instance—that tradi-

tionally have employed mainly

women have expanded in the

past several decades. Also, pop-

ulation in general has shifted

from farms and rural regions to

urban areas, where jobs for

women are more abundant and

more geographically accessible.

The decline in the average

length of the workweek and the

increased availability of part-

time jobs have also made it eas-

ier for women to combine labour

market employment with child-

rearing and household activities.

Changing Preferences and Atti-

tudes Women collectively have

changed their preferences from

household activities to employ-

ment in the labour market. Many

find personal fulfillment in jobs,

careers, and earnings, as evi-

denced by the huge influx of

women into law, medicine, busi-

ness, and other professions.

More broadly, most industrial

societies now widely accept and

encourage labour force partici-

pation by women, including

those with very young children.

Today about 60 percent of Cana-

dian mothers with preschool

children participate in the labour

force, compared to only 30 per-

cent in 1970. More than half

return to work before their

youngest child has reached the

age of two.

Declining Birthrates There were

3.8 lifetime births per woman in

1957 at the peak of the baby

boom. Today the number is less

than 2. This marked decline in

the size of the typical family, the

result of changing lifestyles and

the widespread availability of

birth control, has freed up time

for greater labour-force partici-

pation by women. Not only do

women now have fewer chil-

dren; their children are spaced

closer together in age. Thus

women who leave their jobs dur-

ing their children’s early years

can return to the labour force

sooner. Higher wage rates have

also been at work. On average,

women with relatively high

wage earnings have fewer chil-

dren than women with lower

earnings. The opportunity cost

of children—the income sacri-

ficed by not being employed—

rises as wage earnings rise. In

the language of economics, the

higher “price” associated with

children has reduced the “quan-

tity” of children demanded.

WOMEN AND EXPANDED

PRODUCTION POSSIBILITIES

A large increase in the number of employed women has

shifted the U.S. production possibilities curve outward.

46 Part One • An Introduction to Economics and the Economy

Rising Divorce Rates Marital in-

stability, as evidenced by high

divorce rates, may have moti-

vated many women to enter and

remain in the labour market. Be-

cause alimony and child support

payments are often erratic or

non-existent, the economic im-

pact of divorce on non-working

women may be disastrous. Most

non-working women enter the

labour force for the first time

following divorce. And many

married women—perhaps even

women contemplating marriage

—may have joined the labour

force to protect themselves

against the financial difficulties

of potential divorce.

Slower growth of male wages

The earnings of many low-wage

and middle-wage male workers

grew slowly or even fell in

Canada over the past three

decades. Many wives may have

entered the labour force to en-

sure the rise of household living

standards. The median income

of couples with children grew 25

percent between 1969 and 1996.

Without the mothers’ income,

that growth would have been

only 2 percent. Couples of all in-

come levels may be concerned

about their family income com-

pared to other families. So, the

entry of some women into the

labour force may have encour-

aged still other women to enter

in order to maintain their fami-

lies’ relative standard of living.

Taken together, these factors

have produced a rapid rise in the

presence of women workers in

Canada. This increase in the quan-

tity of resources has helped push

the Canadian production possibil-

ities curve outward. In other

words, it has contributed greatly

to Canada’s economic growth.

chapter summary

1. Economics is grounded on two basic facts:

(a) wants are virtually unlimited; (b) resources

are scarce.

2. Resources may be classified as property re-

sources—raw materials and capital—or as

human resources—labour and entrepreneur-

ial ability. These resources constitute the fac-

tors of production.

3. Economics is concerned with the problem of

using scarce resources to produce the goods

and services that satisfy the material wants of

society. Both full employment and the effi-

cient use of available resources are essential

to maximize want satisfaction.

4. Efficient use of resources consists of produc-

tive efficiency (producing all output combina-

tions in the least costly way) and allocative

efficiency (producing the specific output mix

most desired by society).

5. An economy that is achieving full employ-

ment and productive efficiency—that is oper-

ating on its production possibilities curve—

must sacrifice the output of some types of

goods and services in order to increase the

production of others. Because resources are

not equally productive in all possible uses,

shifting resources from one use to another

brings the law of increasing opportunity costs

into play. The production of additional units of

one product requires the sacrifice of increas-

ing amounts of the other product.

6. Allocative efficiency means operating at the

optimal point on the production possibilities

curve. That point represents the highest-

valued mix of goods and is determined by

expanding the production of each good until

its marginal benefit (MB) equals its marginal

cost (MC).

7. Over time, technological advances and

increases in the quantity and quality of

resources enable the economy to produce

more of all goods and services—that is, to

experience economic growth. Society’s

choice as to the mix of consumer goods and

capital goods in current output is a major

determinant of the future location of the pro-

duction possibilities curve and thus of eco-

nomic growth.

8. The market system and the command system

are the two broad types of economic systems

terms and concepts

chapter two • the economic problem: scarcity, wants, and choices 47

used to address the economic problem. In

the market system (or capitalism) private indi-

viduals own most resources and markets

coordinate most economic activity. In the

command system (or socialism or commu-

nism), government owns most resources and

central planners coordinate most economic

activity.

9. The circular flow model locates the product

and resource markets and shows the major

real and money flows between businesses

and households. Businesses are on the buy-

ing side of the resource market and the selling

side of the product market. Households are on

the selling side of the resource market and the

buying side of the product market.

allocative efficiency, p. 30

capital, p. 28

capital goods, p. 31

circular flow model, p. 43

command system, p. 42

consumer goods, p. 31

economic growth, p. 38

economic problem, p. 27

economic resources, p. 28

economic system, p. 42

entrepreneurial ability, p. 28

factors of production, p. 29

full employment, p. 29

full production, p. 30

investment, p. 28

labour, p. 28

land, p. 28

law of increasing opportunity

costs, p. 34

market system, p. 42

opportunity cost, p. 32

product market, p. 43

production possibilities curve,

p. 32

production possibilities table,

p. 31

productive efficiency, p. 30

resource market, p. 43

utility, p. 27

study questions

1. Explain this statement: “If resources were

unlimited and were freely available, there

would be no subject called economics.”

2. Comment on the following statement from a

newspaper article: “Our junior high school

serves a splendid hot meal for $1 without

costing the taxpayers anything, thanks in

part to a government subsidy.”

3. Critically analyze: “Wants aren’t insatiable. I

can prove it. I get all the coffee I want to

drink every morning at breakfast.” Explain:

“Goods and services are scarce because

resources are scarce.” Analyze: “It is the

nature of all economic problems that

absolute solutions are denied to us.”

4. What are economic resources? What are the

major functions of the entrepreneur?

5.

KEY QUESTION Why is the problem

of unemployment part of the subject matter

of economics? Distinguish between produc-

tive efficiency and allocative efficiency. Give

an illustration of achieving productive, but

not allocative, efficiency.

6.

KEY QUESTION Here is a production

possibilities table for war goods and civilian

goods:

PRODUCTION

ALTERNATIVES

Type of production A B C D E

Automobiles 02468

Rockets 30 27 21 12 0

a. Show these data graphically. Upon what

specific assumptions is this production

possibilities curve based?

b. If the economy is at point C, what is the

cost of one more automobile? One more

rocket? Explain how the production pos-

sibilities curve reflects the law of increas-

ing opportunity costs.

c. What must the economy do to operate at

some point on the production possibili-

ties curve?

7. What is the opportunity cost of attending

college or university? In 1999 nearly 80 per-

cent of Canadians with post-secondary edu-

cation held jobs, whereas only about 40

percent of those who did not finish high

school held jobs. How might this difference

relate to opportunity costs?

8. Suppose you arrive at a store expecting to

pay $100 for an item but learn that a store

two kilometres away is charging $50 for it.

48 Part One • An Introduction to Economics and the Economy

Would you drive there and buy it? How

does your decision benefit you? What is the

opportunity cost of your decision? Now sup-

pose you arrive at a store expecting to pay

$6000 for an item but discover that it costs

$5950 at the other store. Do you make the

same decision as before? Perhaps surpris-

ingly, you should! Explain why.

9.

KEY QUESTION Specify and explain

the shapes of the marginal-benefit and mar-

ginal-cost curves. How are these curves used

to determine the optimal allocation of re-

sources to a particular product? If current

output is such that marginal cost exceeds

marginal benefit, should more or fewer re-

sources be allocated to this product? Explain.

10.

KEY QUESTION Label point G inside

the production possibilities curve you drew

in question 6. What does it indicate? Label

point H outside the curve. What does that

point indicate? What must occur before the

economy can attain the level of production

shown by point H?

11.

KEY QUESTION

Referring again to

question 6, suppose improvement occurs in the

technology of producing rockets but not in the

technology of producing automobiles. Draw

the new production possibilities curve. Now

assume that a technological advance occurs in

producing automobiles but not in producing

rockets. Draw the new production possibilities

curve. Now draw a production possibilities

curve that reflects technological improvement

in the production of both products.

12. Explain how, if at all, each of the following

events affects the location of the production

possibilities curve:

a. Standardized examination scores of high

school, university, and college students

decline.

b. The unemployment rate falls from 9 to 6

percent of the labour force.

c. Defence spending is reduced to allow gov-

ernment to spend more on health care.

d. A new technique improves the efficiency

of extracting copper from ore.

13. Explain: “Affluence tomorrow requires sacri-

fice today.”

14. Suppose that, based on a nation’s produc-

tion possibilities curve, an economy must

sacrifice 10,000 pizzas domestically to get

the one additional industrial robot it desires,

but that it can get the robot from another

country in exchange for 9000 pizzas. Relate

this information to the following statement:

“Through international specialization and

trade, a nation can reduce its opportunity

cost of obtaining goods and thus ‘move out-

side its production possibilities curve.’ ”

15.

Contrast how a market system and a command

economy respond to the economic problem.

16. Distinguish between the resource market

and product market in the circular flow

model. In what way are businesses and

households both sellers and buyers in this

model? What are the flows in the circular

flow model?

17. (Last Word) Which two of the six reasons

listed in the Last Word do you think are

the most important in explaining the rise in

participation of women in the workplace?

Explain your reasoning.

internet application questions

1. More Labour Resources—What is the Evi-

dence for Canada and France? Go to the

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistic’s Web site

www

.bls.gov/ and click Data and then Most

Requested Series. Click International Labor

Statistics and retrieve Canadian employment

data for the period of the last 10 years. How

many more workers were there at the end of

the 10-year period than at the beginning?

Next find the total employment growth of

Italy over the last 10 years. In which of the

two countries did “more labour resources”

have the greatest impact on the nation’s pro-

duction possibilities curve over the 10 years?

2. Relative Size of the Military—Who’s Incur-

ring the Largest Opportunity Cost? To obtain

military goods, a nation must sacrifice civil-

ian goods. Of course, that sacrifice may be

worthwhile in terms of national defence and

protection of national interests. Go to the

U.S. Central Intelligence Agencies Web

site www

.odci.gov/cia/publications/factbook/

country.html to determine the amount of

military expenditures and military expendi-

tures as a percentage of GDP, for each of the

following five nations: Canada, Japan, North

Korea, Russia, and the United States. Who is

bearing the greatest opportunity costs?