McConnell Campbell R., Brue Stanley L., Barbiero Thomas P. Microeconomics. Ninth Edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

IN THIS CHAPTER

IN THIS CHAPTER

Y

Y

OU WILL LEARN:

OU WILL LEARN:

That trade is crucial to

Canada’s economic well-being.

•

The importance of specialization

and comparative advantage in

international trade.

•

How the value of a currency

is established on foreign

exchange markets.

•

The economic costs of

trade barriers.

•

About multilateral trade

agreements and free trade zones.

Canada in

the Global

Economy

B

ackpackers in the wilderness like to

think they are “leaving the world

behind,” but, like Atlas, they carry the

world on their shoulders. Much of their equip-

ment is imported—knives from Switzerland,

rain gear from South Korea, cameras from

Japan, aluminum pots from England, minia-

ture stoves from Sweden, sleeping bags from

China, and compasses from Finland. More-

over, they may have driven to the trailheads in

Japanese-made Toyotas or Swedish-made

Volvos, sipping coffee from Brazil or snacking

on bananas from Honduras.

FIVE

International trade and the global economy affect all of us daily, whether we are hik-

ing in the wilderness, driving our cars, listening to music, or working at our jobs.

We cannot “leave the world behind.” We are enmeshed in a global web of economic

relationships—trading of goods and services, multinational corporations, coopera-

tive ventures among the world’s firms, and ties among the world’s financial mar-

kets. That web is so complex that it is difficult to determine just what is—or isn’t—a

Canadian product. A Finnish company owns Wilson sporting goods; a Swiss com-

pany owns Gerber baby food; and a British corporation owns Burger King. The Toy-

ota Corolla sedan is manufactured in Canada. Many “Canadian” products are made

with components from abroad, and, conversely, many “foreign” products contain

numerous Canadian-produced parts.

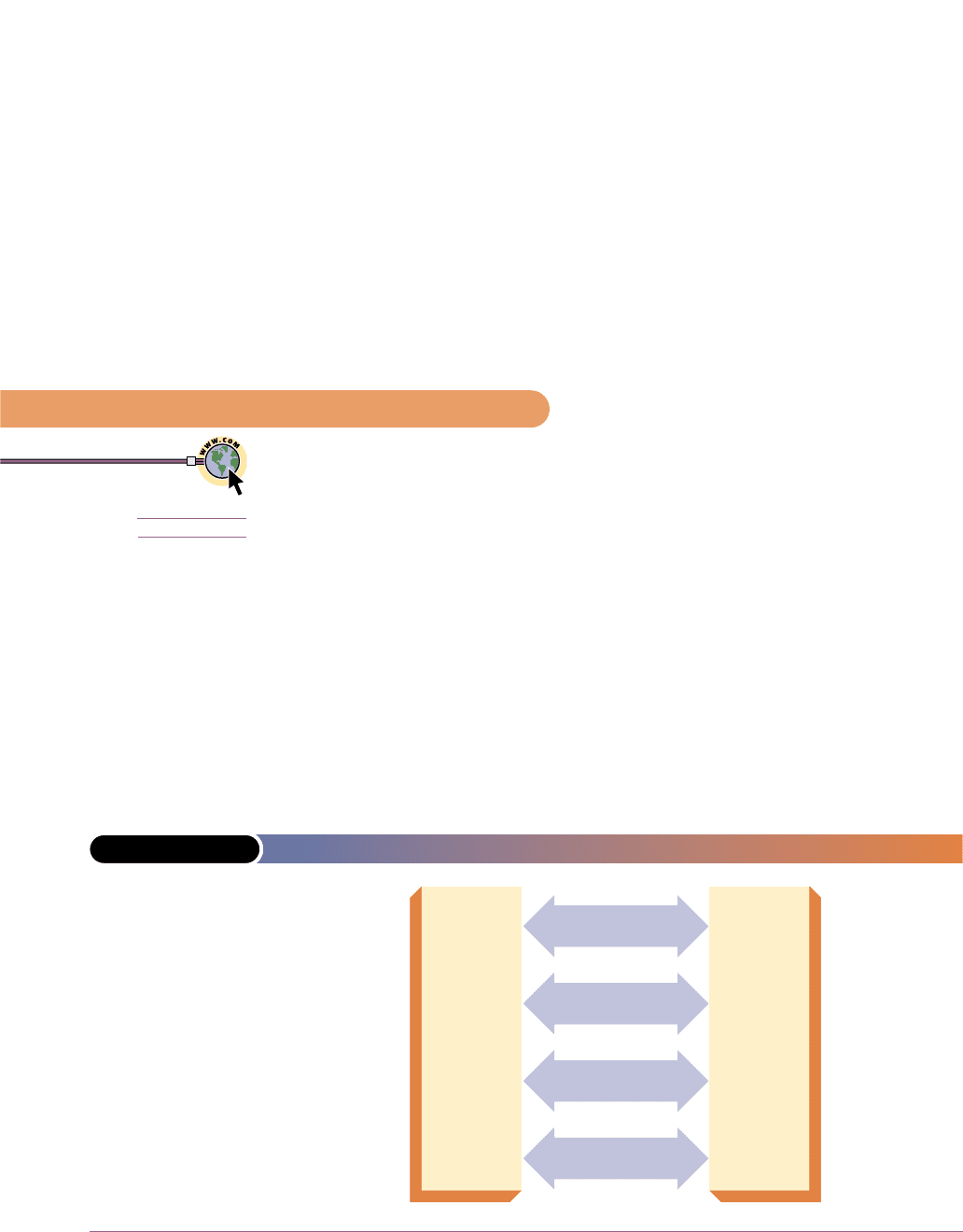

Several economic flows link the Canadian economy and the economies of other

nations. As identified in Figure 5-1, these flows are:

● Goods and services flows or simply trade flows Canada exports goods and

services to other nations and imports goods and services from them.

● Capital and labour flows or simply resource flows Canadian firms establish

production facilities—new capital—in foreign countries and foreign firms

establish production facilities in Canada. Labour also moves between nations.

Each year many foreigners immigrate to Canada and some Canadians move

to other nations.

● Information and technology flows Canada transmits information to other

nations about Canadian products, price, interest rates, and investment oppor-

tunities and receives such information from abroad. Firms in other countries

use technology created in Canada and Canadian businesses incorporate tech-

nology developed abroad.

100 Part One • An Introduction to Economics and the Economy

International Linkages

FIGURE 5-1 INTERNATIONAL LINKAGES

Canadian

economy

Other

national

economies

Goods and services

Capital and labour

Information and

technology

Money

The Canadian econ-

omy is intertwined

with other national

economies through

goods and service

flows (trade flows),

capital and labour

flows (resource

flows), information

and technology flows,

and financial flows.

www.oecd.org/

eco/out/eo.htm

OECD Economic

Outlook

● Financial flows Money is transferred between Canada and other countries

for several purposes, for example, paying for imports, buying foreign assets,

paying interest on debt, and providing foreign aid.

Our main goal in this chapter is to examine trade flows and the financial flows that

pay for them. What is the extent and pattern of international trade and how much

has it grown? Who are the major participants?

Volume and Pattern

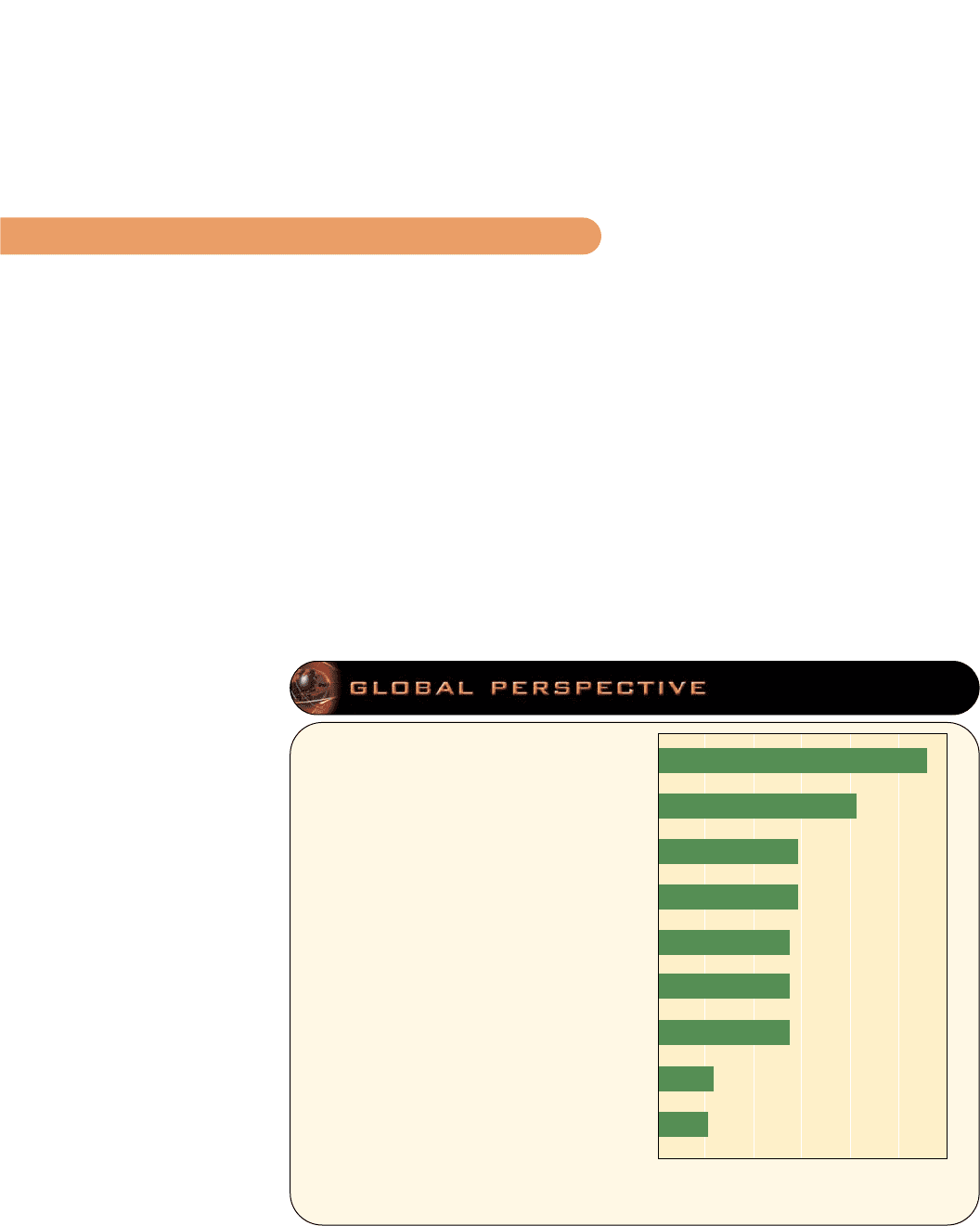

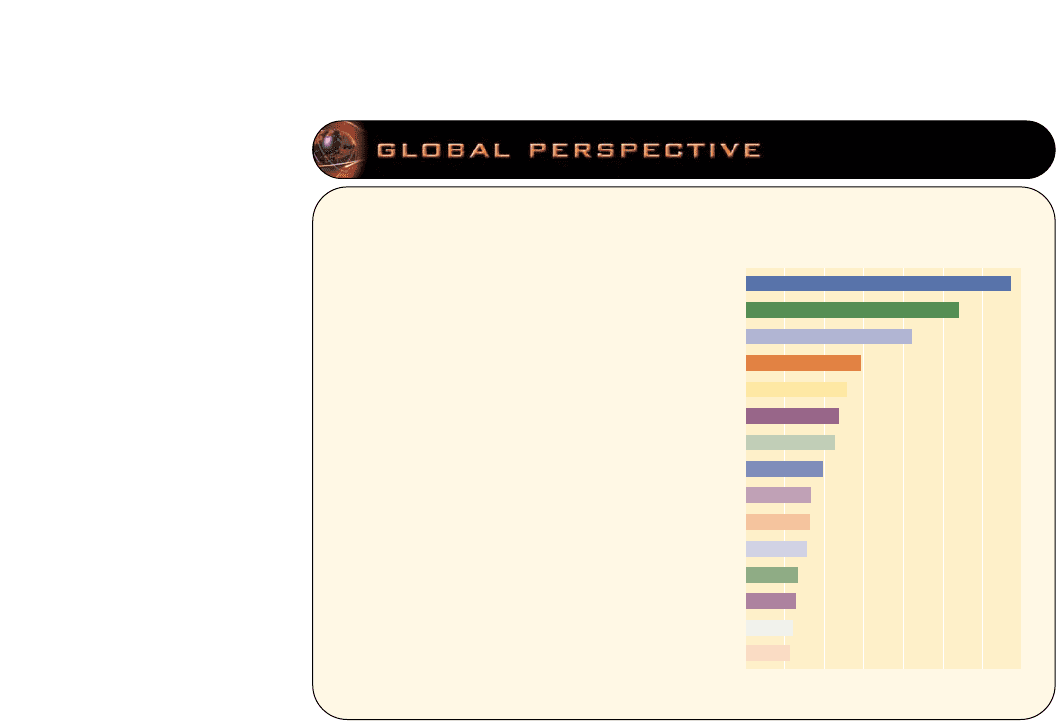

Global Perspective 5.1 suggests the importance of world trade for selected countries.

Canada, with a limited domestic market, cannot efficiently produce the variety of

goods its citizens want. So we must import goods from other nations. That, in turn,

means that we must export, or sell abroad, some of our own products. For Canada,

exports make up about 40 percent of our gross domestic output (GDP)—the market

value of all goods and services produced in an economy. Other countries, the

United States, for example, have a large internal market. Although the total volume

of trade is huge in the United States, it constitutes a much smaller percentage of

GDP than in a number of other nations.

chapter five • canada in the global economy 101

Canada and World Trade

Exports of goods

and services as a

percentage of

GDP, selected

countries, 1999

Canada’s exports

make up almost 40

percent of domestic

output of goods and

services.

5.1

0102030405060

The Netherlands

Germany

New Zealand

Canada

United Kingdom

France

Italy

U.S.A.

Japan

Source: IMF, International Financial Statistics, 2000

VOLUME

For Canada and for the world as a whole the volume of international trade has been

increasing both absolutely and relative to their GDPs. A comparison of the boxed

data in Figure 5-2 reveals substantial growth in the dollar amount of Canadian

exports and imports over the past several decades. The graph shows the growth of

Canadian exports and imports of goods and services as percentages of GDP. Cana-

dian exports and imports currently are approximately 40 percent of GDP, about

double their percentages in 1965.

DEPENDENCE

Canada is almost entirely dependent on other countries for bananas, cocoa, cof-

fee, spices, tea, raw silk, nickel, tin, natural rubber, and diamonds. Imported

goods compete with Canadian goods in many of our domestic markets: Japanese

cars, French and American wines, and Swiss and Austrian snow skis are a few

examples.

Of course, world trade is a two-way street. Many Canadian industries rely on for-

eign markets. Almost all segments of Canadian agriculture rely on sales abroad; for

example, exports of wheat, corn, and tobacco vary from one-fourth to more than

one-half of the total output of those crops. The Canadian computer, chemical, air-

craft, automobile, and machine tool industries, among many others, sell significant

portions of their output in international markets. Table 5-1 shows some of the major

Canadian exports and imports.

102 Part One • An Introduction to Economics and the Economy

FIGURE 5-2 CANADIAN TRADE AS PERCENTAGE OF GDP

Exports

Percentage of GDP

1971

Exports = $21.1 billion

Imports = $19.5 billion

2000

Exports = $475.8 billion

Imports = $427.4 billion

Imports

0

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

2000199519901985198019751971

Canadian imports

and exports of goods

and services have

increased in volume

and have doubled as

a percentage of GDP

since 1971. (Source:

Statistics Canada,

CANSIM, series

D15458 and D15471.)

Visit www.mcgrawhill.

ca/college/mcconnell9

for data update.

TRADE PATTERNS

The following facts will give you an overview of international trade:

● Canada has a trade surplus in goods. In 2000, Canadian exports of goods

exceeded Canadian imports of goods by $54.5 billion.

● Canada has a trade deficit in services (such as accounting services and financial

services). In 2000, Canadian imports of services exceeded export of services by

$6.6 billion.

● Canada imports some of the same categories of goods that it exports, specifi-

cally, automobiles products and machinery and equipment (see Table 5-2).

● As Table 5-2 implies, Canada’s export and import trade is with other industri-

ally advanced nations, not with developing countries. (Although data in this

table are for goods only, the same general pattern applies to services).

● The United States is Canada’s most important trading partner quantitatively.

In 2000, 86 percent of Canadian exported goods were sold to Americans, who

in turn provided 74 percent of Canada’s imports of goods (see Table 5-2).

FINANCIAL LINKAGES

International trade requires complex financial

linkages among nations. How does a nation

obtain more goods from others than it provides

to them? The answer is by either borrowing

from foreigners or by selling real assets (for

example, factories, real estate) to them.

Rapid Trade Growth

Several factors have propelled the rapid growth

of international trade since World War II.

TRANSPORTATION TECHNOLOGY

High transportation costs are a barrier to any

type of trade, particularly among traders who

chapter five • canada in the global economy 103

TABLE 5-1 PRINCIPAL CANADIAN EXPORTS AND IMPORTS

OF GOODS, 2000

Exports % of Total Imports % of Total

Machinery and equipment 25 Machinery and equipment 34

Automotive products 23 Automotive products 21

Industrial goods and materials 15 Industrial goods and materials 19

Forestry products 10 Consumer goods 11

Energy products 13 Agricultural and fishing products 5

Agricultural and fishing products 7 Energy products 5

Source: Statistics Canada, www.statisticscanada.ca/english/Pgdb/Economy/International/gblec05.htm

Visit www.mcgrawhill.ca/college/mcconnell9 for data update.

TABLE 5-2 CANADIAN

EXPORTS AND

IMPORTS OF

GOODS BY AREA,

2000

Percentage Percentage

Exports to of total Imports from of total

United States 86 United States 74

European Union 5 European Union 9

Japan 3 Japan 3

Other countries 6 Other countries 14

Source: Statistics Canada, www.statisticscanada.ca/

english/Pgdb/Economy/International/gblec02a.htm

Visit www.mcgrawhill.ca/college/mcconnell9 for data update.

are distant from one another. But improvements in transportation have shrunk the

globe and have fostered world trade. Airplanes now transport low-weight, high-

value items such as diamonds and semiconductors swiftly from one nation to

another. We now routinely transport oil in massive tankers, significantly lowering

the cost of transportation per barrel. Grain is loaded onto ocean-going ships at mod-

ern, efficient grain silos at Great Lakes and coastal ports. Natural gas flows through

large-diameter pipelines from exporting to importing countries—for instance, from

Russia to Germany and from Canada to the United States.

COMMUNICATIONS TECHNOLOGY

Dramatic improvements in communications technology have also advanced world

trade. Computers, the Internet, telephones, and fax (facsimile) machines now

directly link traders around the world, enabling exporters to assess overseas mar-

kets and to carry out trade deals. A distributor in Vancouver can get a price quote

on 1000 woven baskets in Thailand as quickly as a quote on 1000 laptop computers

in Ontario. Money moves around the world in the blink of an eye. Exchange rates,

stock prices, and interest rates flash onto computer screens nearly simultaneously

in Toronto, London, and Lisbon.

GENERAL DECLINE IN TARIFFS

Tariffs are excise taxes (duties) on imported products. They have had their ups and

downs over the years, but since 1940 they have generally fallen. A glance ahead to

Figure 5-5 shows that Canadian tariffs as a percentage of imports are now about 5

percent, down from over 40 percent in 1940. Many nations still maintain barriers to

free trade, but, on average, tariffs have fallen significantly, thus increasing interna-

tional trade.

Participants in International Trade

All the nations of the world participate to some extent in international trade.

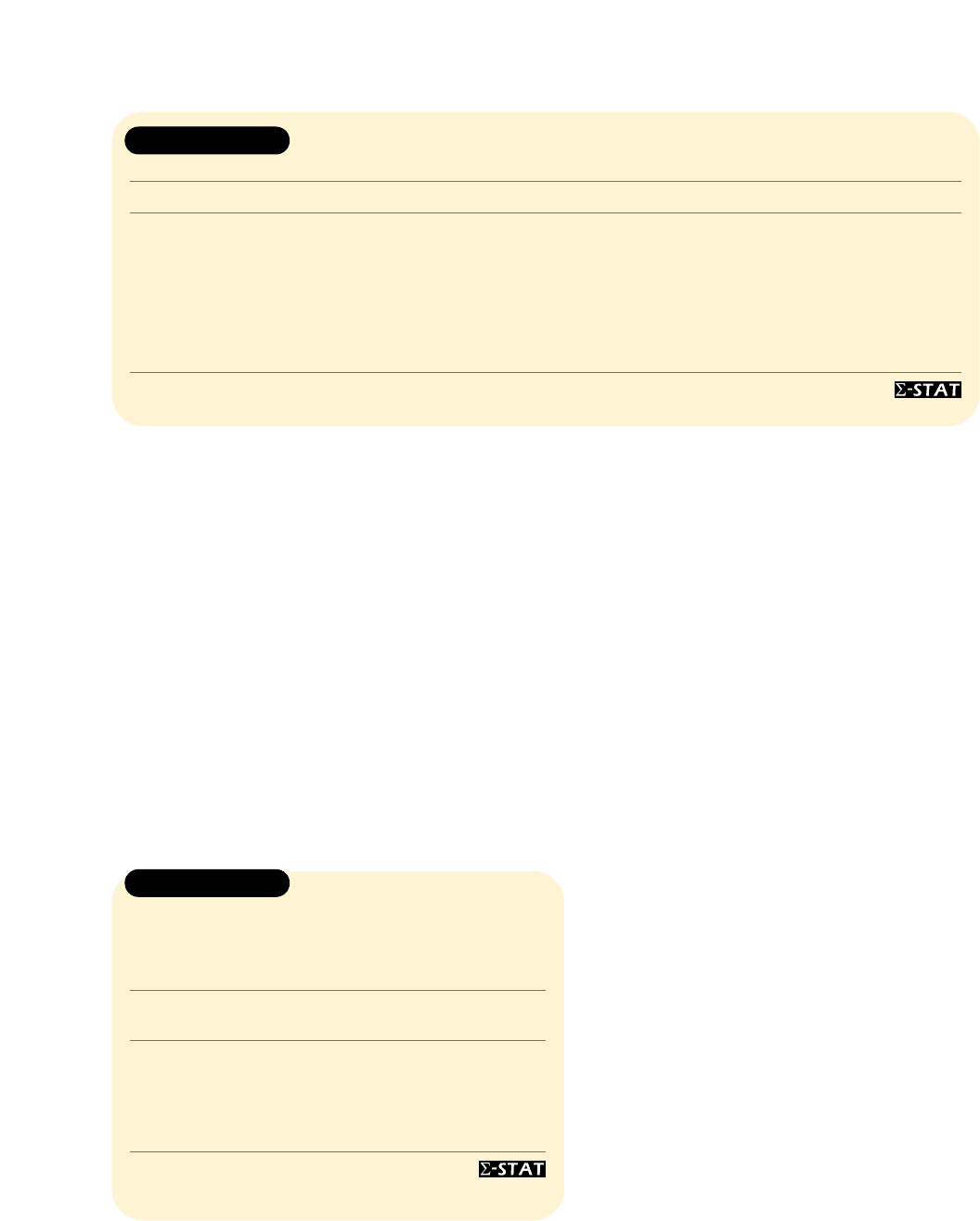

NORTH AMERICA, JAPAN, AND WESTERN EUROPE

As Global Perspective 5.2 indicates, the top participants in world trade by total vol-

ume are the United States, Germany, and Japan. In 1999 those three nations had com-

bined exports of $1.6 trillion. Along with Germany, other Western European nations

such as France, Britain, and Italy are major exporters and importers. Canada is the

world’s sixth largest exporter. Canada, the United States, Japan, and the Western

European nations also form the heart of the world’s financial systems and provide

headquarters for most of the world’s largest multinational corporations—firms that

have sizable production and distribution activities in other countries. Examples of

such firms are Unilever (Netherlands), Nestlé (Switzerland), Coca-Cola (United

States), Bayer Chemicals (Germany), Mitsubishi (Japan), and Nortel (Canada).

NEW PARTICIPANTS

Important new participants have arrived on the world trade scene. One group is

made up of the newly industrializing Asian economies of Hong Kong (now part of

China), Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan. Although these Asian economies

experienced economic difficulties in the 1990s, they have expanded their share of

world exports from about 3 percent in 1972 to more than 10 percent today. Together,

104 Part One • An Introduction to Economics and the Economy

multi-

national

corporation

A firm that owns

production facilities

in other countries

and produces and

sells its product

abroad.

they export about as much as either Germany or Japan and much more than France,

Britain, or Italy. Other economies in southeast Asia, particularly Malaysia and

Indonesia, also have expanded their international trade.

China, with its increasing reliance on the market system, is an emerging major

trader. Since initiating market reforms in 1978, its annual growth of output has aver-

aged 9 percent (compared with 2 to 3 percent annually over that period in Canada).

At this remarkable rate, China’s total output nearly doubles every eight years! An

upsurge of exports and imports has accompanied that expansion of output. In 1989,

Chinese exports and imports were each about $50 billion. In 1999, each topped $200

billion, with 33 percent of China’s exports going to Canada and the United States.

Also, China has been attracting substantial foreign investment (more than $800 bil-

lion since 1990).

The collapse of communism in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union in

the early 1990s altered world trade patterns. Before that collapse, the Eastern Euro-

pean nations of Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and East Germany traded mainly

with the Soviet Union and such political allies as North Korea and Cuba. Today, East

Germany is reunited with West Germany, and Poland, Hungary, and the Czech

Republic have established new trade relationships with Western Europe, Canada,

and the United States.

Russia itself has initiated far-reaching market reforms, including widespread pri-

vatization of industry, and has major trade deals with firms around the globe.

Although its transition to capitalism has been far from smooth, Russia may one day

chapter five • canada in the global economy 105

Comparative exports

The United States, Germany,

and Japan are the world’s

largest exporters. Canada

ranks sixth.

5.2

Exports of goods, 1999

(billions of dollars)

0 100 200 300 400 500 600

United States

Germany

Japan

France

Britain

Canada

Italy

China

Netherlands

Belgium-Lux.

South Korea

Singapore

Mexico

Taiwan

Spain

Source: World Trade Organization, www.wto.org

be a major trading nation. Other former Soviet republics—now independent

nations—such as Estonia and Azerbaijan also have opened their economies to inter-

national trade and finance.

We can easily add “the rest of the world” to Chapter 4’s circular flow model. We do

so in Figure 5-3 via two adjustments.

1. Our previous “Resource Markets” and “Product Markets” now become “Cana-

dian Resource Markets” and “Canadian Product Markets.” Similarly, we add

the modifier “Canadian” to the “Businesses,” “Government,” and “Households”

sectors.

106 Part One • An Introduction to Economics and the Economy

Back to the Circular Flow Model

FIGURE 5-3 THE CIRCULAR FLOW WITH THE FOREIGN SECTOR

CANADIAN

BUSINESSES

CANADIAN

RESOURCE

MARKETS

CANADIAN

GOVERNMENT

(10)

Goods and services

(7)

Expenditures

(8)

Resources

(9)

Goods and services

Net taxes

(11)

Net taxes

(12)

(5)

Expenditures

(6)

Goods and

services

Money income (

r

e

n

t

s

,

w

a

g

e

s

,

i

n

t

e

r

e

s

t

,

p

r

o

f

i

t

s

)

entrepreneuri

a

l

a

b

i

l

i

t

y

(1) Costs

(2) Resources

G

o

o

d

s and services

(4)

(3) Revenue

G

o

o

d

s

a

nd se

r

v

i

c

e

s

C

o

n

s

u

m

ption

e

x

p

e

n

d

i

t

u

r

e

s

REST

OF THE

WORLD

CANADIAN

HOUSEHOLDS

CANADIAN

PRODUCT

MARKETS

(13)

Canadian exports

(14)

Foreign

expenditures

(16)

Canadian imports

(15)

Canadian

expenditures

Land, labour,

c

a

p

i

t

a

l

,

Flows 13–16 in the

lower portion of the

diagram show how

the Canadian econ-

omy interacts with

“The Rest of the

World.” People

abroad buy Canadian

exports, contributing

to our business rev-

enue and money

income. Canadians,

in turn, spend part of

their incomes to buy

imports from abroad.

Income from a

nation’s exports helps

pay for its imports.

2. We place the foreign sector—the “Rest of the World”—so that it interacts

with Canadian Product Markets. This sector designates all foreign nations

that we deal with and the individuals, businesses, and governments that make

them up.

Flow (13) in Figure 5-3 shows that people, businesses, and governments abroad buy

Canadian products—our exports—from our product market. This goods and services

flow of Canadian exports to foreign nations is accompanied by an opposite mone-

tary revenue flow (14) from the rest of the world to us. In response to these revenues

from abroad, Canadian businesses demand more domestic resources (flow 2) to pro-

duce the goods for export; they pay for these resources with revenues from abroad.

Thus, the domestic flow (1) of money income (rents, wages, interest, and profits) to

Canadian households rises.

But our exports are only half the picture. Flow (15) shows that Canadian

households, businesses, and government spend some of their income on for-

eign products. These products, of course, are our imports (flow 16). Purchases of

imports, say, autos and electronic equipment, contribute to foreign output and

income, which in turn provides the means for foreign households to buy Canadian

exports.

Our circular flow model is a simplification that emphasizes product market

effects, but a few other Canada–Rest of the World relationships also require com-

ment. Specifically, there are linkages between the Canadian resource markets and

the rest of the world.

Canada imports and exports not only products, but also resources. For example,

we import some crude oil and export raw logs. Moreover, some Canadian firms

choose to engage in production abroad, which diverts spending on capital from our

domestic resource market to resource markets in other nations. For instance, Nortel

has an assembly plant in Switzerland. Or flowing the other direction, Sony might

construct a plant for manufacturing CD players in Canada.

There are also international flows of labour. About 200,000 immigrants enter

Canada each year. These immigrants expand the availability of labour resources in

Canada, raising our total output and income. On the other hand, immigration tends

to increase the labour supply in certain Canadian labour markets, reducing wage

rates for some types of Canadian labour.

The expanded circular flow model also demonstrates that a nation engaged in

world trade faces potential sources of instability that would not affect a “closed”

nation. Recessions and inflation can be highly contagious among nations. Suppose

the United States experienced a severe recession. As its income declines, its pur-

chases of Canadian exports fall. As a result, flows (13) and (14) in Figure 5-3 decline

and inventories of unsold Canadian goods rise. Canadian firms would respond by

limiting their production and employment, reducing the flow of money income to

Canadian households (flow 1). Recession in the United States in this case con-

tributed to a recession in Canada.

Figure 5-3 also helps us to see that the foreign sector alters resource allocation and

incomes in the Canadian economy. With a foreign sector, we produce more of some

goods (our exports) and fewer of others (our imports) than we would otherwise.

Thus, Canadian labour and other resources are shifted towards export industries

and away from import industries. We use more of our resources to manufacture

autos and telecommunication equipment. So we ask: “Do these shifts of resources

make economic sense? Do they enhance our total output and thus our standard of

living?” We look at some answers next. (Key Question 4)

chapter five • canada in the global economy 107

Specialization and international trade increase the productivity of a nation’s resources and

allow for greater total output than would otherwise be possible. This idea is not new.

Adam Smith pointed it out over 200 years ago. Nations specialize and trade for the

same reasons as individuals do: Specialization and exchange result in greater over-

all output and income.

Basic Principle

In the early 1800s British economist David Ricardo expanded Smith’s idea, observ-

ing that it pays for a person or a country to specialize and exchange even if that per-

son or nation is more productive than a potential trading partner in all economic

activities.

Consider an example of a chartered accountant (CA) who is also a skilled house

painter. Suppose the CA can paint her house in less time than the professional

painter she is thinking of hiring. Also suppose the CA can earn $50 per hour doing

her accounting and must pay the painter $15 per hour. Let’s say that it will take the

accountant 30 hours to paint her house; the painter, 40 hours.

Should the CA take time from her accounting to paint her own house or should

she hire the painter? The CA’s opportunity cost of painting her house is $1500 (= 30

hours × $50 per hour of sacrificed income). The cost of hiring the painter is only $600

(40 hours × $15 per hour paid to the painter). The CA is better at both accounting

and painting—she has an absolute advantage in both accounting and painting. But

her relative advantage (about which more below) is in accounting. She will get her

house painted at a lower cost by specializing in accounting and using some of the earnings

from accounting to hire a house painter.

Similarly, the house painter can reduce his cost of obtaining accounting services

by specializing in painting and using some of his income to hire the CA to prepare

his income tax forms. Suppose that it would take the painter ten hours to prepare

his tax return, while the CA could handle this task in two hours. The house painter

would sacrifice $150 of income (= 10 hours × $15 per hour of sacrificed time) to

accomplish a task that he could hire the CA to do for $100 (= 2 hours × $50 per hour

108 Part One • An Introduction to Economics and the Economy

Specialization and Comparative Advantage

absolute

advantage

When a region or

nation can produce

more of good X and

good Y with less

resources compared

to other regions or

nations.

● There are four main categories of economic

flows linking nations: goods and services flows,

capital and labour flows, information and tech-

nology flows, and financial flows.

● World trade has increased globally and nation-

ally. In terms of volume, Canada is the world’s

seventh largest international trader. With ex-

ports and imports of about 40 percent of GDP,

Canada is more dependent on international

trade than most other nations.

● Advances in transportation and communica-

tions technology and declines in tariffs have all

helped expand world trade.

● North America, Japan, and the Western Euro-

pean nations dominate world trade. Recent new

traders are the Asian economies of Singapore,

South Korea, Taiwan, and China (including Hong

Kong), the Eastern European nations, and the

former Soviet states.

● The circular flow model with foreign trade

includes flows of exports from our domestic

product market, imports to our domestic prod-

uct market, and the corresponding flows of

spending.

Specialization

and Trade