Luscombe D., Riley-Smith J. The New Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. 4: c. 1024-c. 1198, Part 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Zengids, Ayyubids and Seljuqs 751

his reign he scrupulously respected the confederative structure of the empire.

If he was planning a radical reshaping of this structure, he died before he could

take any concrete steps toward that goal. In the siege of 1238 he had even

promised to restore Damascus to al-Nasir Da

ud, the nephew whom he had

dispossessed nine years before. (We cannot of course be sure that he would

have kept his promise; al-Kamil was always a man of flexible principles.) Upon

his death in Damascus in March 1238, al-Kamil’s personal dominions went to

his two sons, al-

Adil II in Egypt and al-Salih Ayyub in the East. Damascus

was left to the discretion of his amirs; they assigned it to one of his nephews,

al-Jawad Yunus, a prince of surpassing obscurity.

In principle, then, the Ayyubid confederation was still intact, along lines

not much different from those laid down by Saladin and al-

Adil. In reality,

everything had changed. No one was happy with the new settlement. It would

break down almost at once, and the internecine wars of the next decade, far

bitterer than any that had preceded them in Ayyubid times, would utterly trans-

form the political system created by Saladin. The dissolution of the Ayyubid

confederation led finally to the centralized military autocracy of the Mamluk

sultanate, but the analysis of these events must be reserved for another chapter.

The century and a half between the death of Malikshah and al-Kamil

Muhammad was clearly a period of intense political decentralization in western

Iran and the Fertile Crescent. However, only sporadically was it an era of po-

litical chaos. What we observe is a competition for autonomy or paramountcy

among local rulers and senior amirs who possessed roughly equal resources.

That competition was governed by well-understood if rarely articulated rules

of politics. Moreover, it was carried out within a rather stable set of fiscal and

administrative practices (the iqta

, the mamluk system, the atabeg and so on).

The dynastic succession, passing from Seljuqids to Zengids to Ayyubids,

marked no deep changes in these rules or practices. However, each of these

dynastic formations did incorporate them in a distinctive way. The Seljuqid

legacy left by Tutush in 1095 was so inchoate that his immediate successors were

unable to organize effective states, nor could any one of them hope to impose

a lasting order on the whole region from Damascus to Mosul. Zengi, schooled

in the Great Seljuqid politics of Baghdad, was no doubt more talented and

determined than his predecessors. He was also luckier, because there was al-

most no one to oppose him between Mosul and Aleppo at the beginning of his

career, and because he lived long enough to convert his first acquisitions into

a solid political structure. He was also fortunate in his successors, particularly

his second son Nur al-Din Mahmud, who knew how to extend and strengthen

his father’s legacy over a long reign. Nur al-Din created an enduring political

framework for his successors; in effect he trained the amirs and administrators

who would build the Ayyubid empire. Saladin, finally, began his career as a

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

752 stephen humphreys

junior amir at Nur al-Din’s court, and clearly acquired an uncommon under-

standing of the workings of Nur al-Din’s political system. What set him apart,

excluding his boldness and astonishing good luck in the summer of 1187, was

his very conscious political planning, his effort to build a complex confedera-

tive structure that could be transmitted from generation to generation. In spite

of the lengthy succession crisis of 1193–1201,hesucceeded remarkably well.

Only half a century after his death did the Ayyubid system of politics begin

to disintegrate. This time, however, it was replaced by a new system, based

on new administrative institutions and sharply different ways of playing the

political game.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

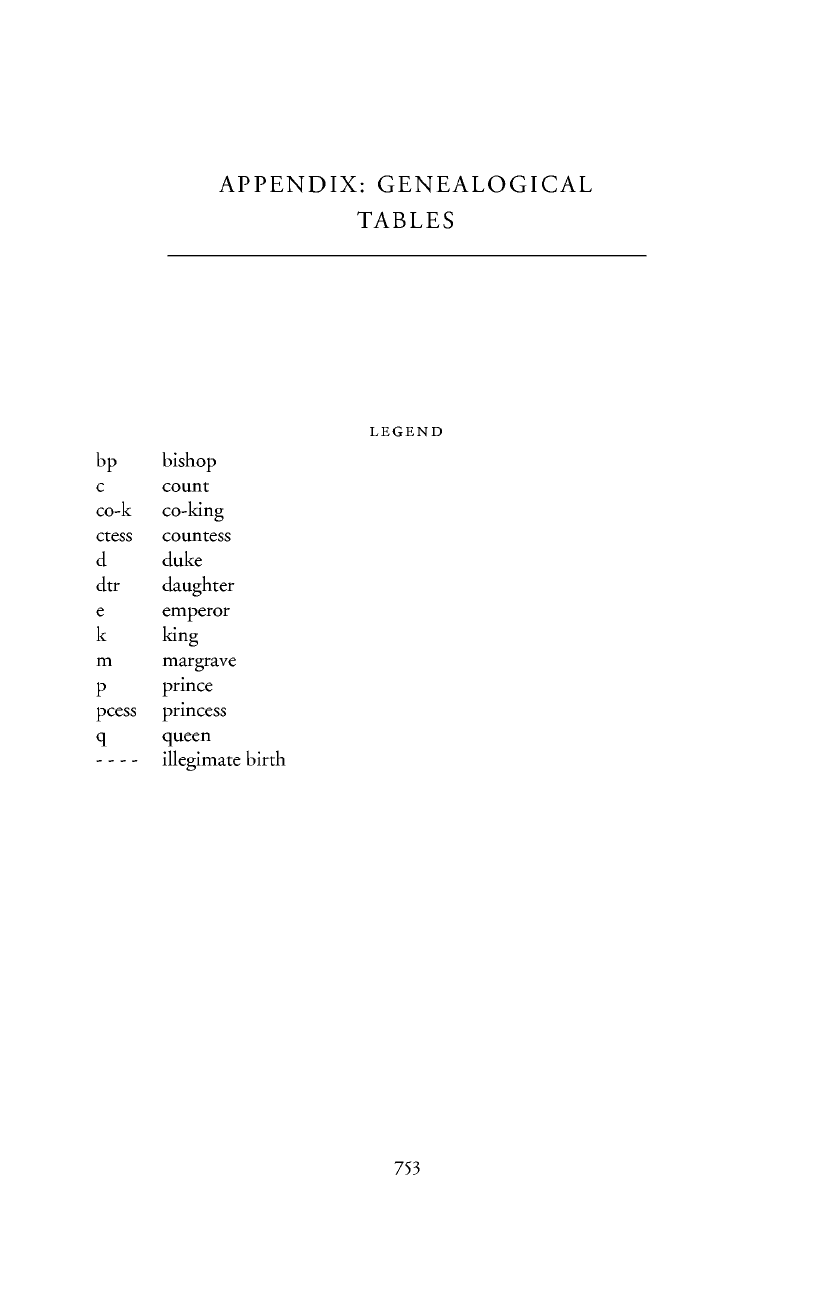

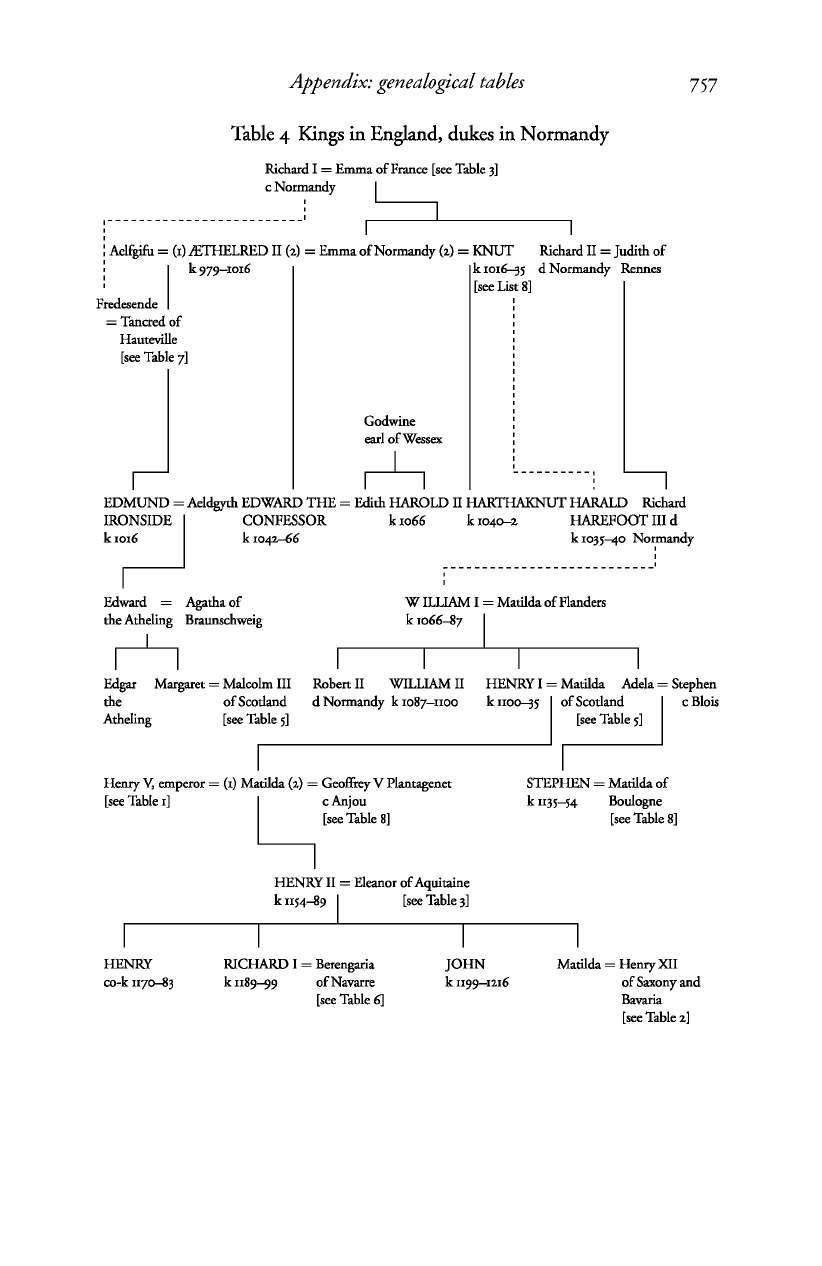

APPENDIX:

GENEALOGICAL

TABLES

LEGEND

bp

c

co-k

esscount ess

d

dtr

e

k

m

P

pcess

q

bishop

count

co-king

countess

duke

daughter

emperor

king

margrave

prince

princess

queen

illegimate birth

753

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

754

Appendix:

genealogical tables

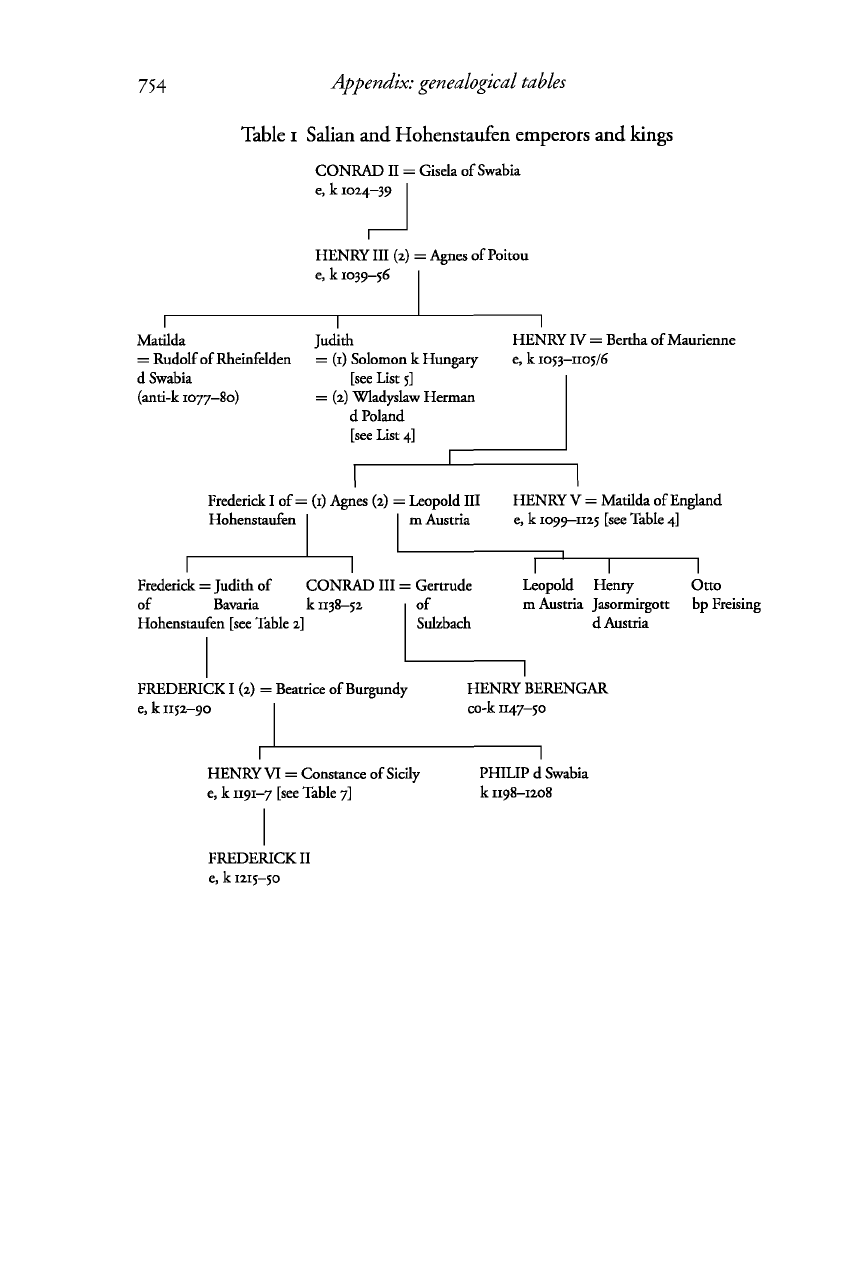

Table i Salian and Hohenstaufen emperors and kings

CONRAD II = Gisela of Swabia

e, k 1024—39

HENRY III (2) = Agnes of Poitou

e, k 1039-56

I

I I

Matilda Judith HENRY IV = Bertha of Maurienne

= Rudolf of Rheinfelden = (i) Solomon k Hungary e, k

1053—1105/6

d Swabia [see List 5]

(anti-k 1077-80) = (2) Wladyslaw Herman

d Poland

[see List 4]

±

Frederick I of =

(1)

Agnes (2) = Leopold III HENRY V = Matilda of England

Hohenstaufen m Austria e, k

1099—1125

[see Table 4]

I

I

Frederick = Judith of CONRAD III = Gertrude

of Bavaria k

1138-52

of

Hohenstaufen [see Table 2] Sulzbach

1

I I

Leopold Henry Otto

m Austria Jasormirgott bp Freising

d Austria

FREDERICK I (2) = Beatrice of Burgundy

e, k 1152-90

HENRY BERENGAR

co-k 1147—50

HENRYVI = Constance of Sicily

e, k

1191—7

[see Table 7]

FREDERICK II

e, k 1215-50

PHILIP d Swabia

k 1198-1208

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Appendix:

genealogical tables

755

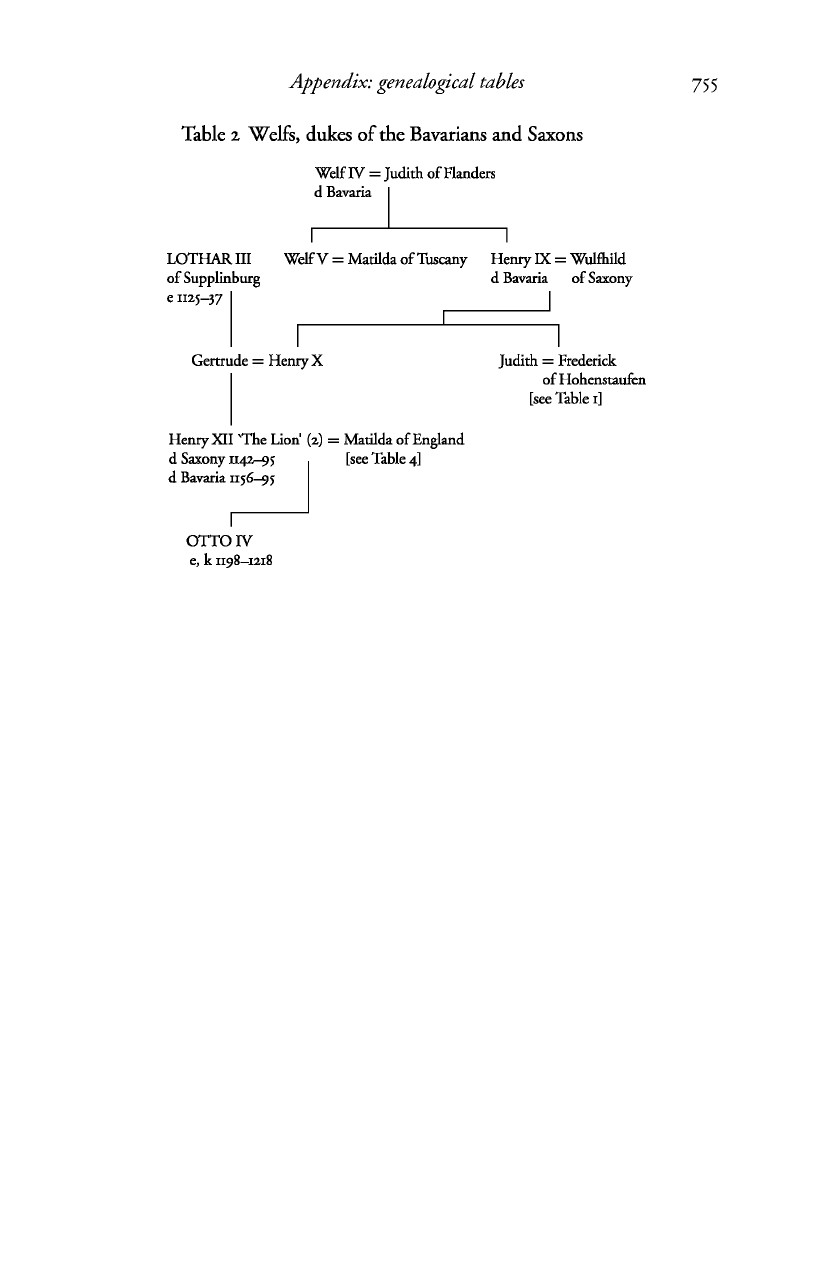

Table 2 Welfs, dukes of the Bavarians and Saxons

Welf IV = Judith of Flanders

d Bavaria

I

I

LOTHARIII WelfV = Matilda of Tuscany Henry IX = Wulfhild

of Supplinburg d Bavaria of Saxony

e1125-37

_£

Gertrude = Henry X

Henry

XII

The Lion

1

(2) = Matilda of England

d Saxony

1142-95

[see Table 4]

d Bavaria 1156-95

Judith = Frederick

of Hohenstaufen

[see Table

1]

OTTO IV

e, k 1198—1218

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

756

Appendix:

genealogical tables

Table

3

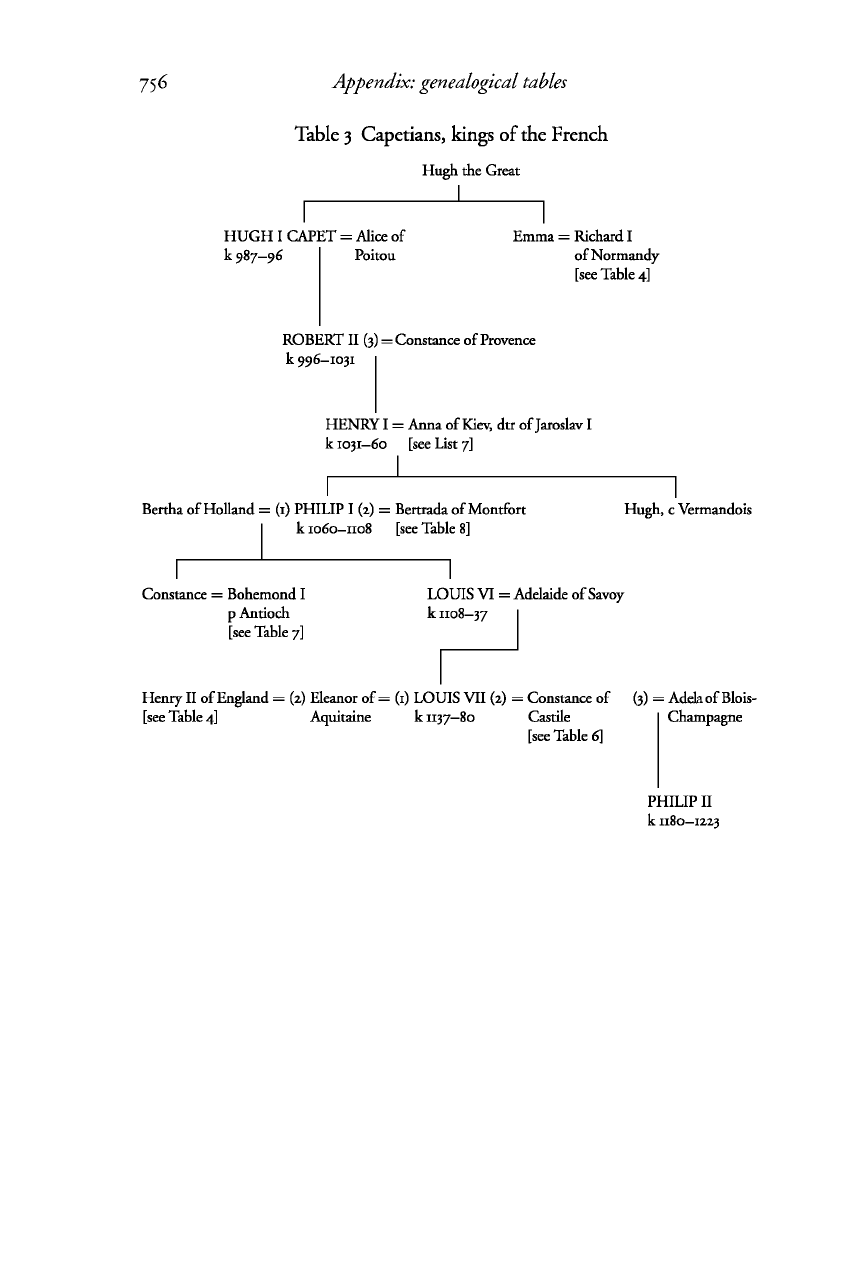

Capetians, kings of the French

Hugh the Great

I

HUGH I CAPET = Alice of

k987-96 Poitou

Emma = Richard I

of Normandy

[see Table 4]

ROBERT II

(3)

= Constance of Provence

k 996—1031

HENRY I = Anna of Kiev, dtr of Jaroslav I

k

1031—60

[see List 7]

Bertha of Holland = (1) PHILIP I (2) = Bertrada of Montfort

k 1060-1108 [see Table 8]

Hugh,

c

Vermandois

Constance = Bohemond I

pAntioch

[see Table 7]

LOUIS VI = Adelaide of Savoy

k 1108-37

Henry II of England = (2) Eleanor of = (1) LOUIS VII (2) = Constance of (3) = Adela of

Blois-

[see Table 4]

Aquitaine k 1137-80 Castile

[see Table 6]

Champagne

PHILIP II

k 1180—1223

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Appendix:

genealogical tables

Table

4

Kings

in England,

dukes

in

Normandy

Richard I = Emma of France [see Table 3]

c Normandy

757

1 1

Aelfgifu =

(1)

jETHELRED II (2) = Emma of Normandy (2) = KNUT Richard II = Judith of

k 979—1016

Fredesende

= Tancred of

Hauteville

[see Table 7]

Godwine

earl of Wessex

k

1016—35

d Normandy Rennes

[see List 8]

EDMUND = Aeldgyth EDWARD THE = Edith HAROLD II HARTHAKNUT HARALD Richard

IRONSIDE I CONFESSOR kio66 k 1040-2 HAREFOOTIIId

kioi6 I k 1042-66 k 1035-^40 Normandy

Edward = Agatha of

the Atheling Braunschweig

WILLIAM I = Matilda of Flanders

k1066-87

Edgar Margaret = Malcolm III Robert II WILLIAM II HENRY I = Matilda Adela = Stephen

the

Atheling [see Table 5]

of Scotland d Normandy kio87—1100 k 1100-35 of Scotland

[see Table 5]

:Blois

Henry

V,

emperor = (1) Matilda (2) = Geofftey V Plantagenet

[see Table

1]

| c Anjou

[see Table 8]

STEPHEN = Matilda of

k

1135—54

Boulogne

[see Table 8]

HENRY II = Eleanor of Aquitaine

k 1154-89 I [see Table 3]

HENRY RICHARD I = Berengaria JOHN

co-k

1170-83

k 1189-99 of Navarre kii99-i2i6

[see Table 6]

Matilda = Henry XII

of Saxony and

Bavaria

[see Table 2]

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

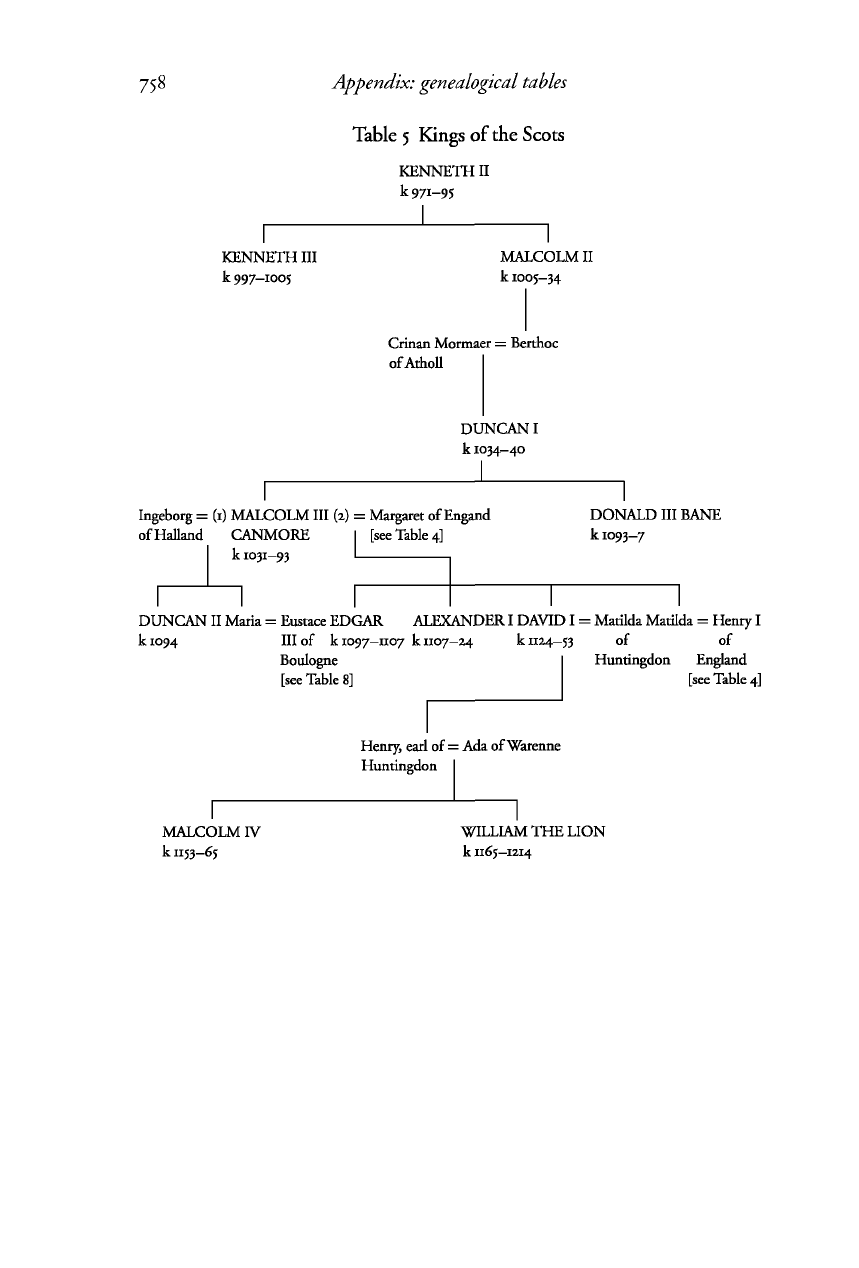

758

Appendix:

genealogical tables

Table

5

Kings of

the

Scots

KENNETH II

k 971-95

KENNETH III

k997-1005

MALCOLM II

k1005—34

Crinan Mormaer = Berthoc

ofAtholl

DUNCAN I

k 1034—40

Ingeborg = (i) MALCOLM III (2) = Margaret of Engand

ofHalland CANMORE I

[see

Table 4]

k

1031-93

I

DONALD III BANE

k1093-7

DUNCAN II Maria = Eustace EDGAR ALEXANDER I DAVID I = Matilda Matilda = Henry I

k

1094

III of k 1097-1107 k 1107-24 k

1124-53

of of

Boulogne

[see

Table 8]

Huntingdon England

[see

Table 4]

Henry, earl of = Ada of Warenne

Huntingdon

MALCOLM IV

k 1153-65

WILLIAM THE LION

k 1165—1214

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

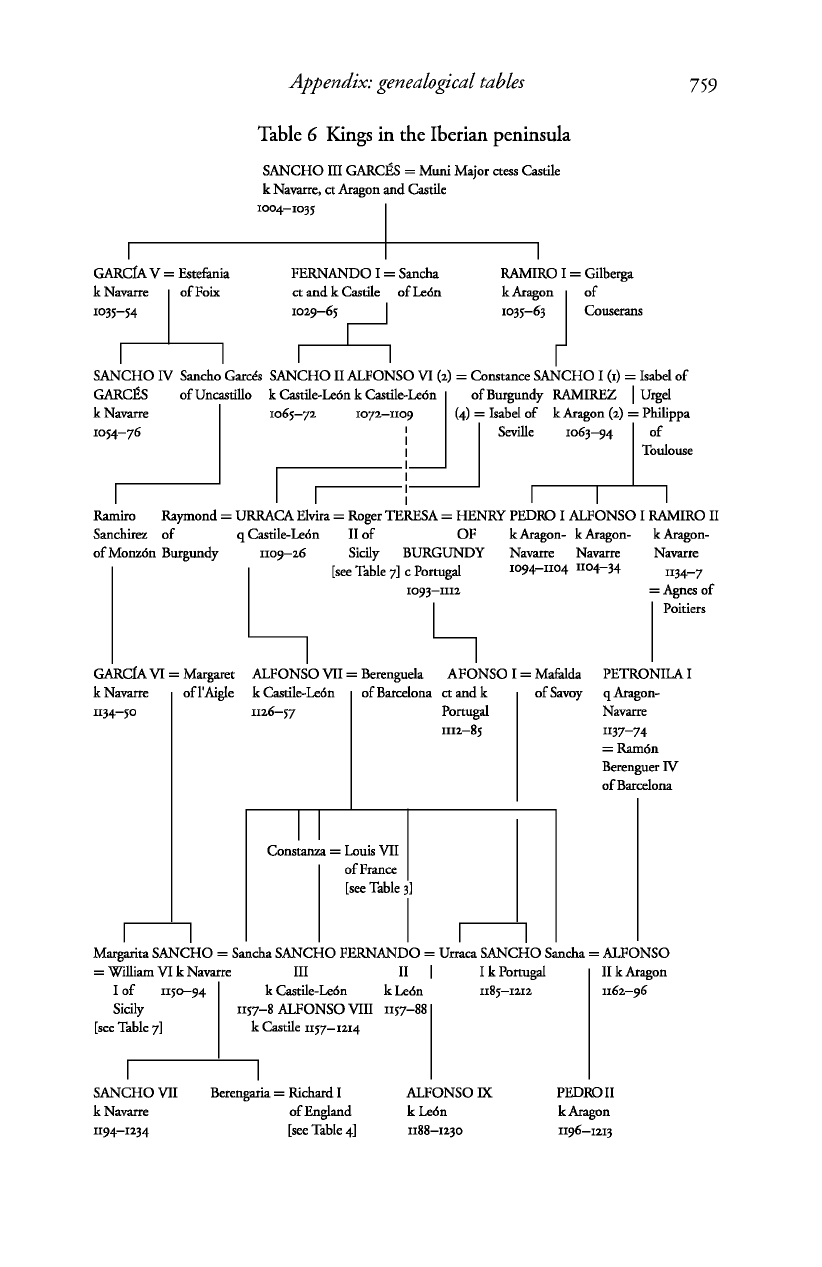

Appendix:

genealogical tables

Table

6

Kings

in

the Iberian peninsula

SANCHO

III

GARCES

=

Muni Major ctess Castile

k Navarre, et Aragon and Castile

1004—1035

759

I

GARClAV

=

Estefania

k Navarre ofFoix

1035-54

FERNANDO

I =

Sancha

et and

k

Castile of Leon

1029—65

I

RAMIRO

I =

Gilberga

k Aragon

i of

1035—63

I

Couserans

SANCHO

IV

Sandio Garces SANCHO II ALFONSO VI

(2) =

Constance SANCHO

I

(1)

=

Isabel

of

GARCES

k Navarre

1054-76

ofUncastillo k Castile-Le6n

k

Castile-Le6n

1065-72 1072-1109

ofBurgundy RAMIREZ

|

Urgel

(4)

=

Isabel

of k

Aragon (2)

=

Philippa

Seville 1063—94 of

Toulouse

Ramiro Raymond

=

URRACA Elvira

=

Roger TERESA

=

HENRY PEDRO

I

ALFONSO

I

RAMIRO

II

Sanchirez

of

ofMonz6n Burgundy

q Castile-Le6n

II of OF

1109-26 Sicily BURGUNDY

[see Table 7]

c

Portugal

1093-1112

k Aragon-

k

Aragon-

Navarre Navarre

1094-1104 1104-34

k Aragon-

Navarre

1134-7

= Agnes

of

Poitiers

GARCIA

VI =

Margaret ALFONSO

VII =

Berenguela AFONSO

I =

Mafalda PETRONILAI

k Navarre ofl'Aigle

k

Castile-Le6n

of

Barcelona

et and k of

Savoy qAragon-

1134—50 1126—57 Portugal Navarre

1112-85 1137-74

= Ram6n

Berenguer

Ttf

of Barcelona

Constanza

=

Louis VII

of France

[see Table 3]

Margarita SANCHO

=

Sancha SANCHO FERNANDO

=

Urraca SANCHO Sancha

=

ALFONSO

= William VI

k

Navarre

I

of

1150-94

Sicily

[see Table

7]

III

k Castile-Le6n

II

I

kLe6n

I

k

Portugal

1185-1212

1157-8 ALFONSO VIII 1157-88

k Castile 1157—1214

II

k

Aragon

1162-96

SANCHO VII

k Navarre

1194-1134

Berengaria

=

Richard

I

of England

[see Table

4]

ALFONSO

K

kLedn

1188-1230

PEDRO II

k Aragon

1196-1213

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

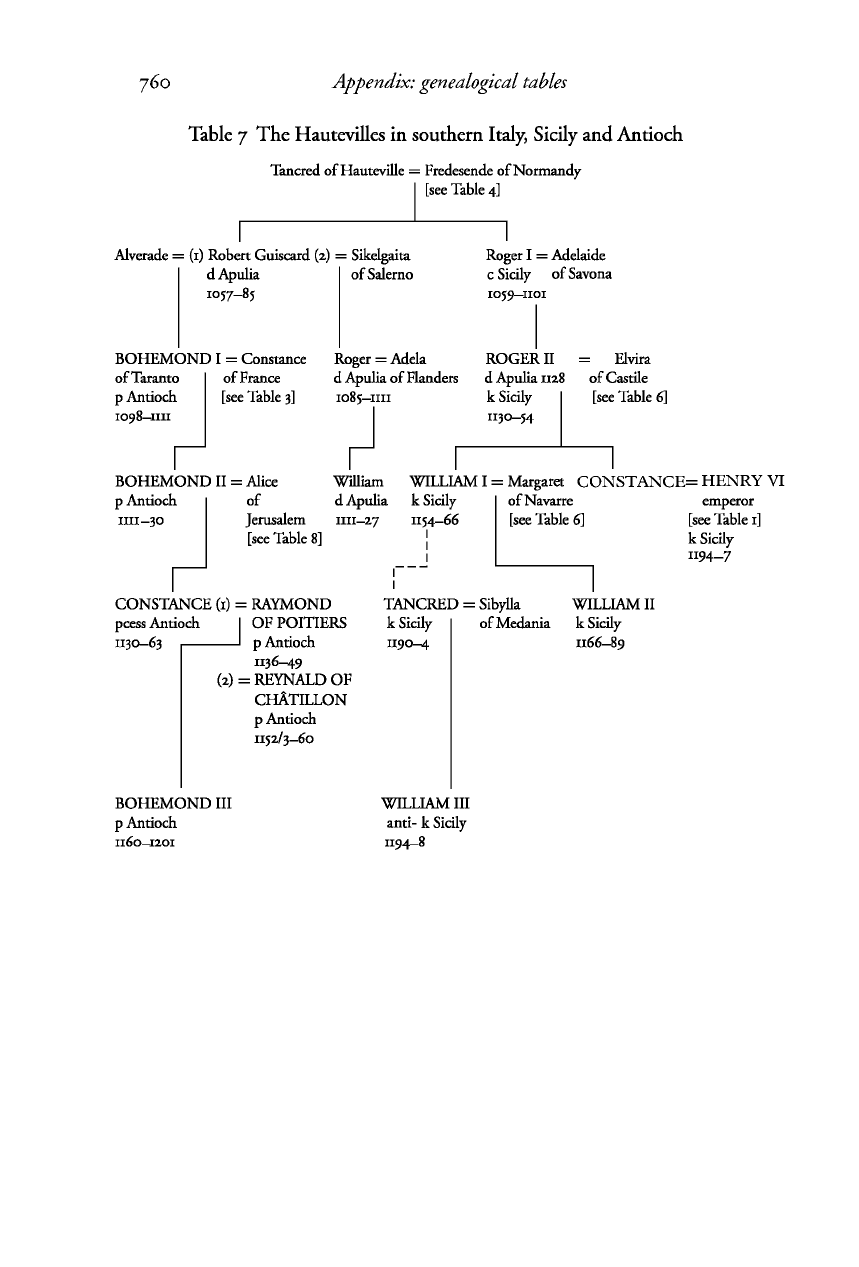

760

Appendix:

genealogical tables

Table

7

The Hautevilles

in

southern Italy, Sicily and Antioch

Tancred of Hauteville

=

Fredesende of Normandy

[see Table

4]

Alverade

=

(1) Robert Guiscard (2)

=

Sikelgaita

d Apulia

1057-85

of Salerno

BOHEMOND

I =

Constance Roger

=

Adela

Roger

I

=

Adelaide

c Sicily ofSavona

1059—1101

ROGER

II

=

Elvira

ofTaranto

p Antioch

1098—mi

of France

[see Table 3]

BOHEMOND 11= Alice

d Apulia of Flanders d Apulia

1128

of Castile

p Antioch

mi—30

of

Jerusalem

[see Table 8]

1085—mi

William

d Apulia

mi—27

k Sicily

1130-54

[see Table

6]

WILLIAM

I

=

Margaret CONSTANCE= HENRY

VI

k Sicily

1154—66

of Navarre

[see Table

6]

emperor

[see Table

1]

k Sicily

II94-7

CONSTANCE (1)

=

RAYMOND

pcess Antioch

1130-63

OF POITIERS

p Antioch

1136-49

(2)

=

REYNALD

OF

CHATILLON

p Antioch

1152/3-60

TANCRED

=

Sibylla

k Sicily

1190-4

ofMedania

WILLIAM

II

k Sicily

1166-89

BOHEMOND

III

p Antioch

1160—1201

WILLIAM

III

ami-

k

Sicily

1194-8

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008