Luscombe D., Riley-Smith J. The New Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. 4: c. 1024-c. 1198, Part 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

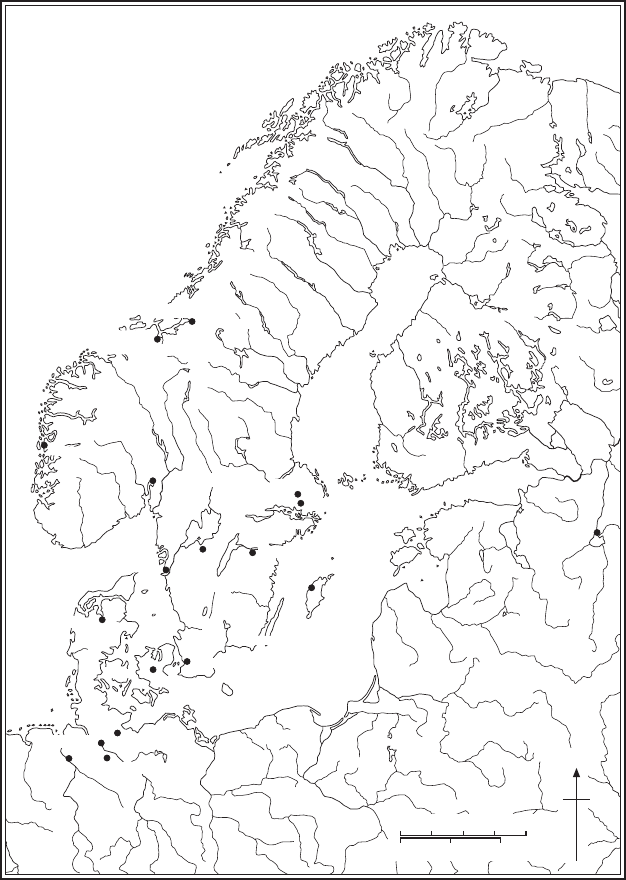

Scandinavia in the eleventh and twelfth centuries 291

N

0 100 200 300 400 km

0 100 200 miles

SVEALAND

Bremen

Hamburg Lübeck

Viborg

J

U

T

L

A

N

D

Odense

Ringsted

Lund

Elbe

Bornholm

Rügen

G

u

l

f

o

f

F

i

n

l

a

n

d

G

u

l

f

o

f

B

o

t

h

n

i

a

Lofoten

Gotland

Oder

Novgorod

Oslo

Vänern

Vättern

Konghelle

Mälaren

Uppsala

Sigtuna

Visby

Trondheim

(Nidaros)

Lüneburg

SKÅNE

GÖTALAND

H

A

L

L

A

N

D

Linköping

Skara

T

R

Ö

N

D

E

L

A

G

Stiklestad

BLEKINGE

Bergen

G

ö

t

a

Äl

v

Map 8 Scandinavia

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

292 peter sawyer

Another, wider, belt of forest lay between the G

¨

otar and the Svear (Old Norse

Sviar, Latin Suiones, Sueones) who lived in the region around Lake M

¨

alaren and

along the east coast of Sweden. The Norwegians were named after the ‘North

Way’, the Atlantic coast of the Scandinavian peninsula, but the name was also

used for people living along the extension of the coast as far as Oslo Fjord, and

for those living in the valleys of rivers that flow into that fjord. Extensive forest

separated the Norwegians from both the G

¨

otar and the Svear.

By the year 1200 most of the territory occupied by these Scandinavians had

been incorporated in the three medieval kingdoms. The Danish kingdom was

the first to be firmly established. At the beginning of the eleventh century Sven

Forkbeard, who had succeeded his father, Harald Bluetooth, as king of the

Danes in 987 after a rebellion, ruled a large territory from Jutland to Sk

˚

ane.

The medieval Danish kingdom at its fullest extent was not much larger; the

only additions, made by 1150 at the latest, were Halland, Blekinge and the

island of Bornholm. Sven was also widely acknowledged as overlord in other

parts of Scandinavia.

There had been attempts to create a Norwegian kingdom based on the

west coast but these had failed and in the first decade of the eleventh century

Norway was under Danish overlordship. It was in the eleventh century that

the Norwegian kingdom was firmly established and by 1100 it extended from

Lofoten in the north to the estuary of G

¨

ota

¨

Alv. Norwegian kings then had

authority in many inland areas of Norway but the territorial consolidation of

the kingdom was not complete until the early thirteenth century.

The Swedish kingdom was formed by the unification of the G

¨

otar and

the Svear. This was a slow process. The first ruler to be called rex Sweorum et

Gothorum was Karl Sverkersson – he was entitled thus in the papal bull creating

the archbishopric of Uppsala in 1164 – but the first Swedish king who is known

to have granted land and privileges in most parts of the kingdom, and who

struck coins in both G

¨

otaland and Svealand, was Knut Eriksson, who died in

1195 or 1196 after a reign of a little more than three decades. There is no reliable

evidence that there was ever a kingdom of the G

¨

otar before the twelfth century,

but the Svea-kingship is well attested as an ancient institution, closely linked

with the pagan rituals celebrated at Uppsala, a famous cult centre north of

M

¨

alaren. During the eleventh and twelfth centuries several kings of the Svear,

including Karl Sverkersson and Knut Eriksson, were G

¨

otar. The Svear seem to

have been willing to accept outsiders rather than promote one of themselves.

The willingness of the Svear to accept kings who were G

¨

otar was a key factor

in forming the medieval kingdom. The process of unification was, however,

hindered by the physical barrier of forest dividing the two peoples and by

religious disunity; pagan rituals continued to be publicly celebrated at Uppsala

for most of the eleventh century.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Scandinavia in the eleventh and twelfth centuries 293

The earliest Scandinavian historians, writing in the twelfth and thirteenth

centuries, believed that the Danish kingdom had existed since time immemorial

and that the kingdoms of Norway and Sweden were relatively recent creations

formed by the unification of many small kingdoms. It is possible that there

were some unrecorded petty kingdoms, but in the first decade of the eleventh

century the only Scandinavian kingdoms mentioned in reliable sources were

those of the Danes and the Svear. They were very different. The territory under

the direct control of the Danish king and his agents had recently been greatly

enlarged but many of his predecessors had, since the eighth century or earlier,

dominated southern Scandinavia. The kingship of the Svear was, in contrast,

predominantly cultic. Effective power was in the hands of the Svea-chieftains,

whose wealth depended on their ability to exact tribute, in particular furs,

from the peoples living round the Gulfs of Bothnia and Finland and in north

Russia. Furs from these northern regions had for centuries been in demand in

Europe, and during the ninth and tenth centuries in the Islamic world too.

As they were of little value unless they could be sold, merchants had to be

encouraged and the peace of markets assured. It appears that the Svear tried

to achieve the stability they needed by acknowledging a king whose functions

were supernatural rather than military.

The king of the Svear contemporary with Sven Forkbeard was Olof, who suc-

ceeded his father Erik in about 995.Hewas a Christian and was therefore unable

to fulfil the traditional role of the Svea-king. He seems only to have had direct

authority over the Svear living in the vicinity of Sigtuna, a royal centre founded

in about 975,probably by Erik, as a base from which a new Christian form of

kingship was gradually extended over the region.

2

Whatever success Erik and

Olof had, their authority was much less than that of their Danish contempo-

raries. That is clearly shown by the progress of conversion in the two kingdoms.

In Denmark Harald Bluetooth was converted and baptized in about 965, and

by the end of the century the process of Christianization was well advanced;

pagan rituals were no longer celebrated in public and pagan forms of burial had

been abandoned. In contrast, although most of the eleventh-century Svea-kings

and many of the Svear were Christian, the pagan rituals at Uppsala continued

until about 1080.By1060 when the diocesan organization of Denmark was

complete, there was only one Swedish bishopric, in V

¨

asterg

¨

otland. It owed its

foundation to Olof who, despite being king, was unable to establish a bishopric

in the M

¨

alar region. The fact that he was able to do so in V

¨

asterg

¨

otland is one

of several indications that he was himself from that region.

In most parts of Scandinavia power was not in the hands of individuals ruling

well-defined territories, but was shared between, and contested by, lords or

2

Tesch (1990); Malmer, Ros and Tesch (1991).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

294 peter sawyer

chieftains each with his own band of men. That was the pattern of government

the Norwegian emigrants took to Iceland in the ninth century. Power in that

Scandinavian colony 200 years later was still divided between some three dozen

chieftains called go

ðar (singular goði ), a title that also occurs on three tenth-

century runic inscriptions on the Danish island of Fyn. A go

ði was a lord

of men, not territory, and he exercised authority publicly together with other

go

ðar in assemblies or things, supported by his thingmen. The number of goðar

was gradually reduced by conquests or more peacefully by marriage alliances,

and this led to a territorialization of their power. By the thirteenth century a

district in which a go

ði claimed authority over everyone could be called a r

´

ıki.

3

A similar process in Scandinavia may have produced small kingdoms that are

unmentioned in contemporary sources, but in some regions the older structure

with multiple lords survived until the thirteenth century, as it did in Iceland.

In Scandinavia, as in Iceland, the population was grouped in numerous local

communities that regulated their own affairs in regular assemblies that were

as much religious and social as legal and political occasions. Some commu-

nities, especially in inland regions, occupied territories that were well defined

by natural boundaries, forest being the most effective barrier, but in coastal

districts or in the relatively open landscapes of Denmark and central Sweden,

where most Scandinavians lived, local communities were not so isolated. Many

were, nevertheless, still largely independent in the early eleventh century, and

retained responsibility for their own affairs after they were incorporated in the

emergent kingdoms. Their assemblies, with some reorganization, were indeed

the main institutions through which royal government was extended in all

three Scandinavian kingdoms.

The assemblies were meetings of the freemen of the community, but in prac-

tice they tended to be dominated by the leading men. Competition between

such men led to some of them being recognized as overlords by those who were

less powerful, or lucky. In the late tenth century H

˚

akon of Lade, now a suburb

of Trondheim, was said by a contemporary poet to have been the overlord of

sixteen ‘jarls,’ a term that was later interpreted as meaning a tributary ruler.

4

H

˚

akon was himself known as a ‘jarl’ for he had acknowledged the Danish king

Harald as his overlord.

The Danish overlordship of Norway was interrupted in 995 by Olav

Tr yggvason, a Norwegian adventurer, whose attempt to revive an independent

Norwegian kingdom was initially successful, largely thanks to the elimination

of Jarl H

˚

akon, but Olav’s triumph was short-lived. In 999 he was defeated and

killed in battle against Sven Forkbeard who thus restored Danish hegemony

3

Sigurðsson (1999).

4

Einarr Helgason, Vellekla, str. 37;Jonsson (1912–15), i, ap. 131, b p. 124.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Scandinavia in the eleventh and twelfth centuries 295

over coastal Norway, with H

˚

akon’s sons, Erik and Sven, as his jarls. Sven Fork-

beard was also acknowledged as lord by many leading G

¨

otar and by some Svear

too.

The success of the Danish kings Harald and Sven in extending Danish

hegemony in Scandinavia was not welcomed by all, and some men who were

unwilling to submit went into exile as Vikings. Successful Vikings could chal-

lenge Danish power, as Olav Tryggvason did. To meet that threat Sven himself

led raids on England to gather plunder and tribute with which he could reward

his supporters and the warriors on whom his power largely depended. Sven’s

attacks on England culminated in his conquest of the kingdom in 1013.For

most of his reign Sven Forkbeard was the most powerful ruler in Scandinavia.

He had many advantages. He could not only draw on the resources of the

most fertile and densely populated region of Scandinavia, but also controlled

the entrance to the Baltic and could, therefore, profit from the flourishing trade

between the lands round that sea and western Europe. The Danes had long

benefited from this traffic but the extension of the Danish kingdom in the

latter part of the tenth century to span

¨

Oresund enabled Harald and Sven to

control it more effectively than their predecessors. This provoked opposition

and, significantly, the first information about relations between the Danes and

the Svear in the tenth century is the report that Erik, king of the Svear, formed

an alliance against the Danes with Mieszko, the Polish ruler, whose daughter he

married. Adam of Bremen, whose Gesta Hammaburgensis Ecclesiae Pontificum,

written in the 1070s, is the main source of information about Scandinavia at

that time, claimed that Sven was defeated and driven into a prolonged ex-

ile. That was a wild exaggeration. Whatever success the allies had, the tables

were soon turned, and Sven marked his triumph by marrying Erik’s Polish

widow and then rejecting her after she had given birth to two sons, Harald and

Knut, and a daughter, Estrid. By the end of the century Erik’s son Olof had

acknowledged Sven as his overlord, and supported him in battle against Olav

Tr yggvason. Olof’s subordination is reflected in his nickname Skotkonungœr

(Mod. Swedish Sk

¨

otkonung). This was first recorded in the thirteenth century

but it was probably given at an early date and meant, according to Snorri

Sturluson, ‘tributary king’, and was equated by him with ‘jarl’.

5

After Sven’s death in February 1014 his empire disintegrated. His son Knut,

who had taken part in the English campaign, was elected king by the army,

but when the English refused to accept him Knut was forced to return to

Denmark. He apparently expected to be recognized as king by the Danes, for

he had some coin dies giving him that title made by English craftsmen.

6

The

Danes had, however, chosen Harald as their king. In 1015 Knut returned to

5

Sawyer (1991b), pp. 27–40.

6

Blackburn (1990).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

296 peter sawyer

England and by the end of 1016 he had reconquered it. It was, therefore, as

king of the English that, after the death of his brother, he was elected king by

the Danes, probably in 1019.

By then Olav Haraldsson, another Viking adventurer, had been recognized

as king by the Norwegians, who once again rejected Danish authority. It was

not until 1028, when he succeeded in driving Olav into exile, that Knut was

able to make good his claim to have inherited the kingship of Norway from

his father. He planned to revive the custom of ruling through a native jarl.

H

˚

akon, grandson of the jarl of Lade who had submitted to Harald Bluetooth,

was the ideal choice but he was drowned in 1029.Olav Haraldsson seized the

opportunity to return from exile in Russia but as he approached Trondheim

Fjord overland from Svealand he was met by enemies and killed in battle

at Stiklestad on 29 July 1030. Knut then made the mistake of attempting to

impose his own son Sven as king of Norway under the tutelage of the boy’s

English mother, Ælfgifu. This was unpopular and the short period of Ælfgifu’s

rule was remembered as a time of harsh and unjust exactions. The Norwegians

soon rebelled and expelled Sven and his mother, perhaps even before Knut

died in 1035.Olav Haraldsson was soon and widely recognized as a martyr.

Hisyoung son Magnus was brought from exile in Russia and acknowledged

as king.

Sven’s death also gave the Svear an opportunity to escape Danish overlord-

ship. Olof Sk

¨

otkonung demonstrated his independence in several ways. He

arranged the marriage of one daughter to Knut’s enemy Olav Haraldsson and

of another to Jaroslav, prince of Kiev. These alliances were clearly directed

against the Danes. It was as much in the interest of the Russians as of the Svear

to undermine Danish control of the route from the Baltic to the markets of

western Europe, and it was Jaroslav who gave refuge to Olav Haraldsson in

1028.Olof Sk

¨

otkonung further defied Knut by inviting Unwan, archbishop of

Hamburg-Bremen, to send a bishop to Sweden at a time Knut did not accept

the archbishop’s authority.

After Olof Sk

¨

otkonung’s death in 1022 his son and successor, Anund, contin-

ued to be hostile to the Danes, and in 1026 he and Olav Haraldsson attacked

Denmark but without success. Although these kings of the Svear refused to

submit to Knut some Svear and G

¨

otar did recognize him as their overlord and

Knut was therefore able to claim, in 1027,tobeking of some of the Svear

(partes Suanorum).

7

Knut died in England in 1035 and was succeeded as king of the Danes by

his son Harthaknut. There was an influential group in England, including

his mother, Emma, who considered that he was Knut’s lawful heir there too.

Harthaknut was, however, unable to leave Denmark for fear of a Norwegian

7

Sawyer (1989).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Scandinavia in the eleventh and twelfth centuries 297

invasion and in his absence the faction that preferred Harald, Knut’s other son

by Ælfgifu, triumphed. It was only after Harald’s death in 1040 that Harthaknut

succeeded his father as king in England. After his death two years later the

Norwegian king Magnus was recognized as king by the Danes; and there are

some indications that this happened while Harthaknut was still alive. The

English feared that Magnus would go further and attempt to emulate Knut

by recreating a North Sea empire, but the expected attack on England did not

happen. Magnus’s hold on Denmark was challenged by Sven Estridsen who,

after the death of Harthaknut was the oldest male representative of the Danish

royal family. He was Knut’s nephew, and had spent the last part of Knut’s reign

in Sweden as an exile. His father, Ulf, had fallen out of favour with Knut;

according to some accounts he was killed on the king’s orders. Sven’s attempts

to displace Magnus had little success; he only gained control of Sk

˚

ane shortly

before Magnus died in 1047.His name then began to appear on coins minted

in Lund, but not as king, while Magnus continued to issue coins as king of the

Danes in Odense and elsewhere in western Denmark.

8

It was only after the

death of Magnus that Sven was accepted as king by the Danes.

For the last two years of his life Magnus shared the kingship of Norway with

his father’s half-brother Harald, known as Hardrada ‘hard-ruler.’ Harald had

returned to Norway in 1045 after serving the Byzantine emperor for more than

ten years in the Varangian Guard. After 1047 he was sole king in Norway. He

too attempted to recreate a North Sea empire but he failed to dislodge Sven

from Denmark and was himself killed at Stamford Bridge in 1066 when he

attempted to conquer England. He was, however, successful in extending the

Norwegian kingdom to include Bohusl

¨

an, and founded a new centre of royal

power at Konghelle on G

¨

ota

¨

Alv, which then formed the boundary with the

Danish kingdom.

By the end of the eleventh century it was the accepted rule in both Norway

and Denmark that only members of the royal families could become kings. All

Danish kings after Sven Estridsen were his descendants, and he himself was

grandson of Sven Forkbeard. It has been claimed that the hereditary principle

was accepted even earlier in Norway and that all Norwegian kings were de-

scendants of Harald Fine-hair. That is, however, a fiction.

9

Harald’s dynasty

ended with the death of his grandson in about 970 and neither Olav Tryggva-

son nor Olav Haraldsson were his descendants. The founder of the medieval

Norwegian dynasty was Harald Hardrada.

The limitation of kingship to members of the royal families did not eliminate

the need to make a choice. This was normally done by the leading men,

sometimes after a fight, but the successful claimant had to be recognized in

public assemblies. Sometimes different assemblies chose different candidates

8

Becker (1981).

9

Krag (1989).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

298 peter sawyer

and there were numerous occasions when joint kings were chosen, either by

agreement or in rivalry. There was no tradition of primogeniture; all the sons of

a king had a claim to succeed. After the death of Sven Estridsen in 1074 some of

his numerous sons thought they should rule jointly. That did not happen and

five of them succeeded in turn. It was in the next generation that the succession

was more violently disputed between the sons of the last two, Erik and Niels.

Forashort while there were three kings but the conflict ended in 1157 when

Erik’s grandson Valdemar emerged as victorious. He restored stability for a

while and was succeeded in turn by his two legitimate sons, Knut (1182–1202)

and Valdemar II (1202–41).

Norway was far more extensive than Denmark and had a much shorter

tradition of unity. After Harald Hardrada the normal pattern was for the

sons of the last king to rule jointly. They apparently did so in relative peace

until the death of King Sigurd ‘the Crusader’ in 1130. Civil war then broke

out and continued, with intervals, until 1208.Inthe 1160s the faction led by

Erling Skakke gained the upper hand for a while. His wife was King Sigurd’s

daughter and their young son Magnus was elected king in 1161.Two years later

an attempt was made to regulate the order of succession, but these rules were

not respected and kings continued to be chosen by different assemblies for the

next sixty years.

Magnus was opposed by several rivals who claimed to be the sons of previous

kings but most were defeated by his father. The most serious challenger was

Sverri who arrived in 1177 from the Faeroes claiming to be the son of a

Norwegian King. He was soon recognized as king in Tr

¨

ondelag and by 1184

he had defeated and killed both Erling and Magnus. Many Norwegians nev-

ertheless would not recognize him as their king and Øystein, archbishop of

Nidaros, refused to crown him. Instead Bishop Nicholas of Oslo did so in

1194, but shortly afterwards Nicholas joined and became one of the leaders of a

newly formed opposition group. Conflict between the two factions continued

after Sverri’s death in 1202, and it was not until 1217 that Sverri’s grandson

H

˚

akon was recognized as king throughout Norway.

Sweden was the last kingdom to be established and it was not until the

latter part of the twelfth century that Swedish kings had to be members of a

royal family. Before that the Svear elected, or recognized, several kings who

were not of royal descent, including Sverker, who was king from about 1132

to his assassination in 1156, and his successor Erik who was killed in 1160.For

100 years all Swedish kings were descendants of these two men and both were

G

¨

otar.Sverker was from

¨

Osterg

¨

otland and Erik from V

¨

asterg

¨

otland.

The linkage of the two peoples was powerfully reinforced in 1164 by the cre-

ation of the archiepiscopal province of Uppsala, which included the G

¨

otaland

sees of Skara and Link

¨

oping as well as three in Svealand. Provincial councils

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Scandinavia in the eleventh and twelfth centuries 299

summoned by the archbishop of Uppsala, or by papal legates, were the first

national councils of Sweden. The same is true of Norway, where the arch-

bishopric of Nidaros was established in 1152 or 1153. That province was the

precursor of the Norwegian kingdom at its fullest extent for in addition to the

five Norwegian sees it included the sees that had been established in Iceland,

Greenland and other Norwegian colonies. It was, however, a century before

Iceland and Greenland were incorporated in the kingdom.

The church contributed to the consolidation of the kingdoms in many

other ways. The clergy were literate and were members of an international

organization based on written law, with a relatively elaborate machinery to

implement it. The role of kings as upholders of justice was emphasized by

churchmen who also encouraged kings to act as law-makers, in the first place

in the interest of the clergy and their churches.

In Norway special assemblies known as law-things were beginning to make

or change law by the tenth century. Their early history is obscure but by the

thirteenth century there were four. There were similar assemblies in other parts

of Scandinavia. Some met in places such as Viborg or Odense that had been

the sites of assemblies in pre-Christian times and later became episcopal sees.

The creation of these law-making assemblies was an important stage in the

formation of the kingdoms. The laws made in them were influenced by kings

as well as churchmen, but kings ruled by consent and had to respect existing

rights. There were, consequently, in each kingdom significant differences in

the law of different provinces when written versions were produced between

the twelfth and fourteenth centuries. It was not until the thirteenth century

that Scandinavian kings began to issue law codes for their entire kingdoms.

The earliest of the provincial laws, for the west Norwegian province known

as Gulating, survives in a twelfth-century version. It shows how magnates

acted as royal agents, leading military levies, supporting stewards of royal es-

tates, arresting wrong-doers and choosing representatives to attend the annual

law-thing. It also has provisions designed to prevent such men abusing their

authority by interfering in the legal process. Clergy, in particular bishops, were

also important royal agents. Their influence is manifest in attempts to limit

the number of potential claimants to succeed as king by excluding illegitimate

sons. That doctrine was only accepted slowly – in Norway not until 1240s;

and even then illegitimate sons were not completely excluded from the order

of succession. Churchmen, as well as kings, favoured hereditary succession,

but this was only made law in Norway. In Denmark and Sweden the magnates

were powerful enough to retain the right to elect their kings on most occa-

sions. Churchmen also attempted to strengthen the position of kings against

the claims of potential rivals by the ceremony of coronation. There must al-

ways have been inauguration rituals but little is known about them before

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

300 peter sawyer

the twelfth century when ecclesiastical coronation, on the model developed in

tenth-century Germany, was introduced. The first Scandinavian coronation

was of Magnus Erlingsson in 1163 or 1164.His rival and successor, Sverri, at-

tempted to secure his position by coronation but he and his supporters argued

that he was king by God’s grace which was bestowed directly, not mediated

by the church. This view triumphed in Norway and was well expressed in the

King’s Mirror,atreatise on kingship written in the 1250s that reflects a political

ideology that may be described as almost absolutist, with the king ruling by

divine right as God’s representative, chosen not by human electors but by in-

heritance. The first Danish coronation ceremony was in 1170 on the initiative of

Valdemar I, whose attitude seems to have been very much the same as Sverri’s.

He had his eldest son designated and crowned in a ceremony at Ringsted. In

Sweden, where the first recorded coronation was in 1210, the claims of rival

dynasties made such ecclesiatical confirmation all the more valuable.

The interaction of the church and kingship was also displayed in the recog-

nition of royal saints. By 1200 each kingdom had at least one. Olav Haraldsson

in Nidaros; Sven Estridsen’s son Knut, who was killed in Odense in 1086;

Valdemar I’s father, Knut Lavard, who was murdered by a rival in 1134, and

whose sanctity was proclaimed during the coronation ceremony at Ringsted in

1170.InSweden Erik, killed at Uppsala in 1160, was soon treated as a martyr,

but his cult developed slowly.

Despite the efforts of kings and churchmen to ensure stability there were

frequent and violent conflicts in most parts of Scandinavia during the eleventh

and twelfth centuries. This was partly because kings were not rich or powerful

enough to overawe or decisively defeat rivals and rebellious magnates. By the

end of the eleventh century Scandinavian rulers could not realistically hope

to gather wealth in Russia, the Byzantine empire or in England. They were

forced to rely on their own resources, together with what they could gather

as plunder or tribute from each other or from the peoples living round the

Baltic. It is significant that the periods of stability coincided with the reigns of

kings who were able to enlarge their kingdoms. Thus, Norway was relatively

peaceful after the death of Harald Hardrada; his son and successor was indeed

known as Olav Kyrre ‘the peaceful’. This may have been in part due to the

death of many magnates alongside Harald in England but another factor was

the success of Harald and his successors in extending the kingdom. By the

end of the century Norwegian kings could draw on the resources of the whole

coast at least as far north as Lofoten, and in the south to G

¨

ota

¨

Alv. The Arctic

region was particularly valuable for, as explained below, there was a growing

demand in western Europe for its produce at that time. Similarly, Valdemar I

and his son Knut owed much of their success in Denmark to their conquest of

Slav territory. By 1169 Valdemar had conquered R

¨

ugen and in 1185 the prince

of the Pomeranians submitted to Knut, who was well placed to take advantage

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008