Luscombe D., Riley-Smith J. The New Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. 4: c. 1024-c. 1198, Part 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

England and Normandy, 1042–1137 211

up of developments in England and the increased use of the same instruments

in Normandy. The sealed writ became an essential element in the royal gov-

ernment. Numbers of scribes increased, though some charters, particularly in

Normandy, were written by the beneficiaries and taken to the king for authen-

tication. There was, however, only one seal and one keeper of the seal and, once

arudimentary chancery began to emerge towards the end of Henry’s reign, one

chancellor. Other household officials – the chamberlains, constables and mar-

shals – might be more localized. Nevertheless, some officers were mobile; for

example Robert Mauduit served in the treasuries of both countries and Robert

de la Haye, constable of Lincoln Castle, served at another time as a baron of

the exchequer in Normandy.

All three of the first Norman kings necessarily divided their time between

England and Normandy and were obliged to leave kinsfolk or trusted magnates

to act as vice-regents in their place during their absence. William I often left

his wife Matilda as his representative in Normandy. In England he relied at

first on William fitz Osbern and then on Odo of Bayeux until Odo’s disgrace.

Archbishop Lanfranc had an important role in transmitting the king’s orders,

and both Robert of Mortain and Geoffrey bishop of Coutances were frequently

commissioned to act in important pleas. When William Rufus governed Nor-

mandy during his brother’s absence on crusade he employed an official of a

new type in England: Ranulf Flambard, who had emerged as one of the ablest

of the clerks in the royal household at the end of the Conqueror’s reign. Ranulf

never had quite the status of the later justiciar, but his duties were both judicial

and fiscal. Henry was absent for long periods in Normandy; though the central

curia remained the nucleus of all important business the practical difficulties

arising from his movements and the steady increase in administrative business

made it necessary to begin to detach more tightly organized departments of

government from the household-court on both sides of the Channel. Until 1118

Henry’s queen Matilda was the official regent in England during his absences,

but Roger bishop of Salisbury gradually took over more of the vice-regal du-

ties, and after her death emerged as second after the king. A small group of

men, including Robert Bloet bishop of Lincoln, Richard Belmeis bishop of

London, Adam of Port and Ralph Basset, were frequently associated with him,

acting both as justices in pleas that did not follow the king and presiding over

financial business. In Normandy John bishop of Lisieux performed similar

functions during Henry’s years in England.

Finance was crucial, and the need to meet recurring threats of invasion or

rebellion, particularly in Normandy, determined many of Henry’s decisions.

He had to provide at all times for the knights serving in his household troops

or as garrisons in his castles on the Norman frontiers and wherever feudal obli-

gations were insufficient to meet the needs of defence. The periods of greatest

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

212 marjorie chibnall

danger were from the time he secured Normandy in 1106 to 1113, and in the

1120s when William Clito, supported by Louis VI, posed a real threat to the

succession; and these saw the most vigorous financial reforms. It was necessary

to control the unruly retinues of knights and household servants, whose rav-

agings had made the journeys of the court during the reign of Rufus a terror to

the neighbourhood. By 1108 Henry had introduced greater discipline both by

ruthlessly punishing abuses and by planning his perambulations in advance so

that orderly arrangements for provisioning could be made. The evidence of the

1130 Pipe Roll shows how the sheriffs planned ahead to provide wine, wheat and

clothing and much more besides for the needs of the itinerant household. His

first great reform of the moneyers came in 1108; there was an even more radical

overhaul in 1125, when he reduced the number of mints and finally abandoned

the regular cycles of recoinage inherited from Anglo-Saxon England.

16

As more

and more of both the produce from the royal demesne and the feudal obliga-

tions of vassals were converted into financial payments the need for tight control

of the collection of cash and efficient auditing of receipts became necessary.

A momentous innovation took place in England in the first ten years of the

twelfth century; by 1110 a central receipt and audit was held at the same place

and in the same curial session. Still an event, not an institution, it was known as

the Exchequer from the checked cloth of the abacus on which calculations were

made as the sheriffs and other officers brought in their cash receipts and the

tallies for sums already disbursed. The court met regularly twice a year, initially

at Winchester; its composition varied from time to time, and the magnates

active in each session, called barons of the Exchequer, handled judicial no less

than financial business. Roger of Salisbury presided without ever being called

treasurer–atitle later given to his nephew Nigel. For convenience money

continued to be stored in repositories in several places, including the Tower

of London and Westminster as well as Winchester in England, and Caen and

Falaise in Normandy. The treasure needed for day-to-day expenses was carried

with the king, in the charge of a household chamberlain. Before the end of the

reign, possibly only in the last few years, a central receipt and audit had begun

to be held in Normandy at Caen, at a separate Exchequer presided over by

John bishop of Lisieux.

17

There was close contact between the financial agents

on both sides of the Channel; and though some chamberlains were active

only on one side, information and experience were exchanged. The position

of the treasurer, as described in the Constitutio Domus Regis at the end of

Henry’s reign, was still anomalous; half in the household and half out of it, he

possibly supervised all the chamberlains and had overall responsibility for all the

treasuries, English and Norman. There were similarities in organization at the

16

Blackburn (1991).

17

Green (1989), pp. 115–23.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

England and Normandy, 1042–1137 213

level of the household; but, because the position of the English sheriffs differed

from that of the vicomtes who were responsible for farming and collecting

the Norman revenues and there was no Norman equivalent of the county

court, differences were bound to persist. The first surviving English record

of the central audit, the Pipe Roll of 1129–30 antedates anything available

for Normandy; later Norman Exchequer Rolls (from 1172) show common

influences offset by variations in local practice.

In judicial matters also, even though a single curia regis,moving with the

king, might handle cases from any part of the realm wherever it happened to

be, the development of institutions of government tended to ‘perpetuate and

intensify the different traditions and customs of the two countries’.

18

So the

application of law through different local courts made in the long run for a

good deal of variation below the baronial level, while the upper ranks of feudal

society were tending towards greater uniformity all over the realm. At that level,

intermarriage, attendance at the royal court, service in the royal household and

widespread travel both on the king’s business and to oversee their own far-flung

estates, produced assimilation of the Normans, Bretons, Flemings, Poitevins

and others within two or three generations of the conquest and settlement of

England. The law of free inheritance was becoming more defined; by the end

of Henry’s reign the flexible inheritance customs within the family that had

previously existed were moving decisively towards primogeniture for military

tenures in England, and in Normandy towards a droit d’a

ˆ

ınesse with its rule that

fiefs were impartible. There was enough similarity for cases involving cross-

Channel lordships to be settled in the curia regis in the king’s presence. And

similar instruments were used; the sealed writ and the inquest at the king’s

command were ubiquitous in the Anglo-Norman realm.

At times from the reign of the Conqueror onwards justices were sent out with

special commissions; Henry I sometimes appointed justices or justiciars to hear

pleas in several counties. They dealt with cases initiated by writ, and the forms

of judicial writs were multiplying. These writs, which appeared in both England

and Normandy, were specifically designed for a particular set of circumstances.

The cases, however, were still heard in the local courts and judgement was

pronounced in the traditional way even when a royal officer presided; the

fundamental change whereby the officers themselves gave judgement did not

come until the reign of Henry II. Although the germ of later developments

may now be seen in the language of the writs and in the widening sphere of

action of the justices, this did not imply an inevitable development towards

the methods of dispensing justice which took a much clearer shape in the later

reign.

19

18

Le Patourel (1976), p. 223.

19

Brand (1990).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

214 marjorie chibnall

In many cases brought to his notice Henry insisted that the proper place

for them to be heard was in the lord’s court, where land pleas between vas-

sals were dealt with and feudal dues were enforced. Where the competence of

these courts failed, perhaps because men held of different lords, or if justice

was denied, he was prepared to have cases transferred to the county courts in

England, or ultimately to hear them in his own presence in the curia regis.

Some, arising out of financial disputes revealed in the audit, were heard by

the barons of the Exchequer. The initiative normally lay with the plaintiff.

The king did not go out to seek justice, but he offered it widely and the

profits of justice and jurisdiction were, after land, one of the most impor-

tant sources of revenue. Below the king’s court there were some differences

in the administration of justice in England and Normandy. Tenants-in-chief

held their own feudal courts for their own barons, and these interlocked with

the king’s court in different ways. Little is known of the functioning of the

early vicomtes’ courts in Normandy; they certainly never had the communal

element of the county courts to which, in England, some cases found their

way. The vicomtes, like Landry of Orbec, appear to have brought criminal

cases into their courts by impleading suspects ex officio.

20

It was an intensely

unpopular practice which easily led to extortion, and though used occasion-

ally for a short while under Henry I it had no future in England. The or-

ganization of the county courts lent itself to the initiation of criminal pros-

ecutions through juries of presentment which were to become general under

Henry II.

Bishops, in so far as they were barons, were liable to come under the same

jurisdiction as the lay magnates, though they fought hard to limit their secular

liabilities. Their position in both England and Normandy was similar. Eccle-

siastical patronage and the control of appointments was equally important to

the king in both. The early recognition in Normandy that investment by the

duke with the temporalities did not involve spiritual investiture, which was

performed by a prelate, meant that in the Anglo-Norman realm the investiture

contest never had the same violence as in the empire even after the spread

of ecclesiastical reform. The struggle came with the increasing formalities in-

volved in the feudal relationships of prelates as great tenants-in-chief; it was

resolved in time by agreeing that homage might be performed before conse-

cration. Election did not become a major problem until later; the kings usually

succeeded in having their nominee accepted in a technically correct formal

election, or at least reached a working agreement without open conflict. The

extent of royal influence appears in the large number of bishoprics held by

clerks who had served in the royal household; promotion to a bishopric was a

20

Van Caenegem (1976), pp. 61–70.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

England and Normandy, 1042–1137 215

valuable form of patronage at a time when patronage helped to guarantee the

devotion of the king’s servants at every level. The experience of these men in

ecclesiastical business made up a part of their training for more secular duties

when they served on judicial commissions. John, archdeacon of S

´

ees, had had

long experience of judicial business in church courts before Henry made him

bishop of Lisieux in 1107, and he became the key figure in the development of

aNorman Exchequer.

Henry I, up to his death, maintained his rights of regale. Complaints, when

they came, were less about elections and more about sees being left vacant for

long periods while the king’s officers collected the revenues. New strains were

beginning to appear when Stephen succeeded with a doubtful title and needed

papal backing just when reformers were demanding a stricter application of

canon law. As far as the spiritual jurisdiction of the church courts went, it

was slowly being disentangled from temporal business, with a good deal of

confusion in areas of overlapping jurisdiction. The question of the activities

of bishops in the shire courts was naturally peculiar to England. In the main,

problems arising from the increasing activities of the archdeacons’ courts and

the strengthening of the hierarchy, which led to appeals, were broadly similar

in all parts of the realm and routine appeals to Rome had not yet become a

bone of contention.

It was still possible in 1137, when the struggle between Stephen and Matilda

entered a new phase, for a ruler to hold together, in a single realm, many

different provinces with considerable variations in custom. Boundaries might

vary as frontier provinces changed hands. In the north of England the claims of

the kings of Scotland were tenacious; it would have been possible for Cumbria

and perhaps Northumberland to be drawn into their kingdom. The Channel

was not an insuperable barrier, and Henry I may have believed that Normandy

could in time be brought fully under his royal authority. Nevertheless, the

claims of the kings of France were ancient and were never abandoned. An

important change in the nature of fealty worked to their advantage. As the

concept of liege homage replaced the looser bonds of loyalty that had once

prevailed, Louis VII showed clearly that he would be satisfied with nothing

less than homage performed in Paris by the duke of Normandy in person, not

in the marches by his son as previously. Possibly the struggle between Stephen

and Matilda made the break-up of the realm inevitable; possibly it merely

hastened the change that drew Normandy decisively away from England into

the kingdom of France. The work of the first three Norman kings established

arealm bound together by personal ties, with many common instruments of

government and a powerful central nucleus in the king’s court and household.

At the same time, any increase in the establishment of local courts for the king’s

business and localized finance would be likely to enhance regional divisions.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

216 marjorie chibnall

The permanent establishment of individual branches of cross-Channel families

in England tended to break family ties faster than cross-Channel marriages

could strengthen them. Paris was too near not to be a threat and the kings of

France were constantly vigilant for any weakening of Anglo-Norman power.

They seized each opportunity when it came, as it did with the outbreak of civil

war.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

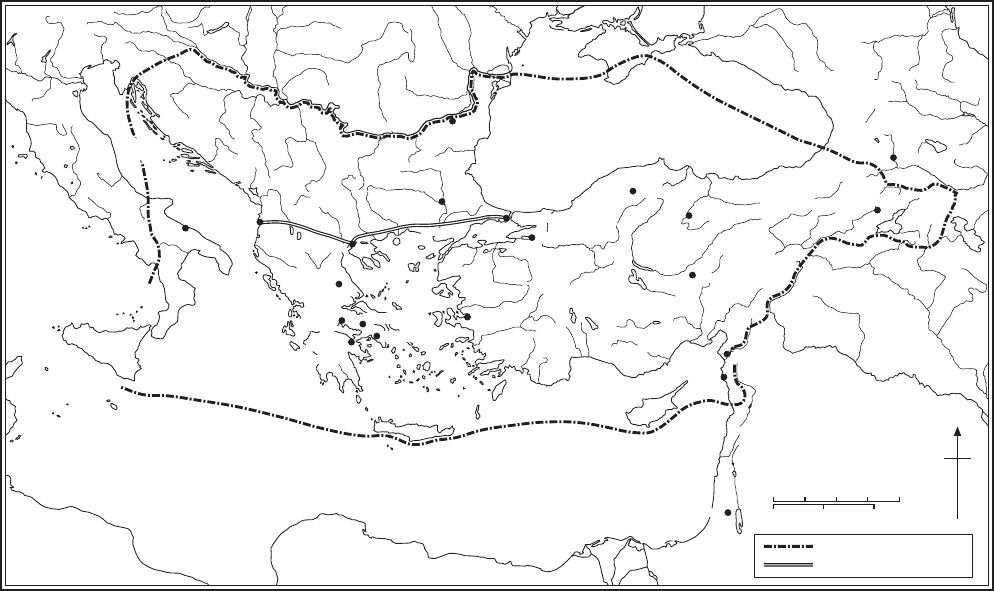

chapter 8

THE BYZANTINE EMPIRE, 1025–1118

Michael Angold

i

basil ii died on 15 December 1025 after a reign of almost fifty years. He left

Byzantium the dominant power of the Balkans and Near East, with apparently

secure frontiers along the Danube, in the Armenian highlands and beyond

the Euphrates. Fifty years later Byzantium was struggling for its existence.

All its frontiers were breached. Its Anatolian heartland was being settled by

Tu r kish nomads; its Danubian provinces were occupied by another nomad

people, the Petcheneks; while its southern Italian bridgehead was swept away

by Norman adventurers. It was an astonishing reversal of fortunes. Almost

as astonishing was the recovery that the Byzantine empire then made under

Alexios I Komnenos (1081–1118). These were years of political turmoil, financial

crisis and social upheaval, but it was also a time of cultural and intellectual

innovation and achievement. The monastery churches of Nea Moni, on the

island of Chios, of Hosios Loukas, near Delphi, and of Daphni, on the outskirts

of Athens, were built and decorated in this period. They provide a glimmer of

grander monuments built in Constantinople in the eleventh century, which

have not survived: such as the Peribleptos and St George of the Mangana. The

miniatures of the Theodore Psalter of 1066 are not only beautifully executed

but are also a reminder that eleventh-century Constantinople saw a powerful

movement for monastic renewal. This counterbalanced but did not necessarily

contradict a growing interest in classical education. The leading figure was

Michael Psellos. He injected new life into the practice of rhetoric and in his

hands the writing of history took on a new shape and purpose. He claimed

with some exaggeration to have revived the study of philosophy single-handed.

His interest in philosophy was mainly rhetorical. It was left to his pupil John

Italos to apply philosophy to theology and to reopen debate on some of the

fundamentals of Christian dogma.

217

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

N

0

100 200 300 400 km

0

100 200 miles

A

E

G

E

A

N

S

E

A

Jerusalem

SYRIA

Eup

h

r

at

e

s

CYPRUS

Bari

Laodicea

Antioch

Caesarea

C

I

L

I

C

I

A

MELITENE

ARMENIA

Manzikert

Constantinople

Nicaea

BLACK SEA

Kastamon

Ani

C

a

u

c

a

s

u

s

A

N A

T

O

L

I

A

Smyrna

Chios

CRETE

PELOPONNESE

Corinth

Athens

HELLAS

IONIAN

SEA

TYRRHENIAN

SEA

SICILY

D

r

a

v

a

S

a

v

a

D

a

n

u

b

e

Adrianople

M

a

r

it

s

a

Thessalonica

B

U

L

G

A

R

I

A

A

L

B

A

N

I

A

Durazzo

(Dyrrachion)

Thebes

Delphi

Larissa

THESSALY

THRACE

C

A

L

A

B

R

I

A

A

P

U

L

I

A

A

D

R

I

A T

I

C

S

E

A

Tigris

Boundaries of the Empire

Via Egnatia

Lake

Van

Dristra

Amaseia

Map 5

The Byzantine empire in the eleventh century

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The Byzantine empire, 1025–1118 219

Modern historiography has singled out the period from 1025 to 1118 as the

watershed of Byzantine history. G. Ostrogorsky has provided the classic in-

terpretation.

1

He saw the eleventh century as the beginning of Byzantium’s

inexorable decline, which he attributed to the triumph of feudalism. Private

interest gained at the expense of the state. Without effective central institutions

it was impossible to mobilize the resources of the empire or provide any clear

direction. Symptomatic of the decline of central authority was the struggle for

power between the civil and military aristocracies. The latter emerged victori-

ous with the accession to the throne of Alexios I Komnenos. But his success

was limited and his restoration of the empire superficial, because ‘the Empire

was internally played out’. Ostrogorsky meant by this that the peasantry and

their property were coming increasingly under the control of great landowners.

He believed that this compromised the economic and demographic potential

of the empire.

Ostrogorsky’s presentation of the history of the Byzantine empire in the

eleventh century has been attacked from two main directions. P. Lemerle

doubted that the eleventh century was a period of absolute decline at Byzan-

tium.

2

There is too much evidence of economic growth and cultural vitality,

which he connects with ‘le gouvernement des philosophes’. The tragedy was

Alexios I Komnenos’s seizure of power, which substituted family rule for the

state. R. Browning would add that Alexios damped down the intellectual and

religious ferment of the eleventh century through the deliberate use of heresy

trials.

3

A. P. Kazhdan takes a rather different view.

4

He agrees that in the eleventh

century Byzantium prospered. He attributes the political weakness of the

empire to reactionary elements holding back the process of ‘feudalization’.

A. Harvey presses this approach to extremes.

5

He insists that the advance of

the great estate was essential for economic and demographic growth. Kazhdan

is also struck by the buoyancy and innovation of Byzantine culture. He con-

nects this with a growth of individualism and personal relations. It was a victory

for progressive elements, which were promoted rather than hindered by the

Comnenian regime.

6

Such a bald presentation does not do justice to the subtleties and hesitations

displayed by the different historians nor to their skilful deployment of the

1

G. Ostrogorsky, AHistory of the Byzantine State, trans. J. Hussey, Oxford (1968), pp. 316–75.

2

P. Lemerle, Cinq

´

etudes sur le XIe si

`

ecle byzantin (Le Monde Byzantin), Paris (1977), pp. 249–312.

3

R. Browning, ‘Enlightenment and repression in Byzantium in the eleventh and twelfth centuries’,

PaP 69 (1975), 3–22.

4

A. P. Kazhdan and A. W. Epstein, Change in Byzantine Culture in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries,

Berkeley, Los Angeles and London (1985), pp. 24–73.

5

A. Harvey, Economic Expansion in the Byzantine Empire 900–1200, Cambridge (1989), pp. 35–79.

6

A. P. Kazhdan and S. Franklin, Studies on Byzantine Literature of the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries,

Cambridge (1984), pp. 242–55.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

220 michael angold

evidence. It makes their views far more schematic than they are, but it highlights

differences of approach and isolates the major problems. They hinge on the

effectiveness of the state. Was this being undermined by social, economic and

political developments? Though their chronology is different Ostrogorsky and

Lemerle are both agreed that it was. They assume that the health of Byzantium

depended on the centralization of power. By way of contrast Kazhdan believes

that imperial authority could be rebuilt on a different basis and this is what

Alexios Komnenos was able to do. The nature of Alexios’s achievement becomes

the key issue.

Aweakness of all these readings of Byzantium’s ‘eleventh-century crisis’ is

a willingness to take Basil II’s achievement at face value; to see his reign as

representing an ideal state of affairs. They forget that his iron rule represents

an aberration in the exercise of imperial authority at Byzantium. His complete

ascendancy was without precedent. In a series of civil wars in the early part of

his reign he destroyed the power of the great Anatolian families, such as Phokas

and Skleros, but only thanks to foreign aid. He used his power to straitjacket

Byzantine society and subordinate it to his autocratic authority. To this end

he reissued and extended the agrarian legislation of his forebears. Its purpose

was ostensibly to protect peasant property from the ‘powerful’ as they were

called. It was, in practice, less a matter of the imperial government’s professed

concern for the well-being of the peasantry; much more a way of assuring

its tax revenues. These depended on the integrity of the village community

which was the basic tax unit. This was threatened as more and more peasant

property passed into the hands of the ‘powerful’. Basil II followed up this

measure by making the latter responsible for any arrears of taxation which had

till then largely been borne by the peasantry. Control of the peasantry was vital

if Basil II was to keep the empire on a war footing, while keeping the empire on

a war footing was a justification for autocracy. The long war he waged against

the Bulgarians only finally came to an end in 1018.Itexploited the energies

of the military families of Anatolia. It cowered the aristocracy of the Greek

lands. They were terrified that they would be accused of cooperating with the

Bulgarians. The war with the Bulgarians was bloody and exhausting, but it was

a matter of recovering lost ground, not of gaining new territory. The Bulgarian

lands had been annexed by John Tzimiskes in the aftermath of his victory over

the Russians in 971.Itwas only the civil wars at the beginning of Basil II’s reign

and the emperor’s own ineptitude that allowed the Bulgarians to recover their

independence. Basil II’s triumph over the Bulgarians gave a false impression of

the strength of the empire.

In part, it depended on an absence of external enemies. Islam was for the

time being a spent force; thanks to Byzantium’s clients, the Petcheneks, con-

ditions on the steppes were stable; the Armenians were hopelessly divided;

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008