Lawson B. How Designers Think: The Design Process Demystified

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

This must also ring very true to any architect who has designed for

a committee client. I have found that one of the most effective

ways of making apparent the disparate needs of groups in multi-

user buildings such as hospitals is to present the client committee

with a sketch design. Clients often seem to find it easier to

communicate their wishes by reacting to and criticising a proposed

design, than by trying to draw up an abstract comprehensive per-

formance specification.

This discussion has oversimplified reality by implicitly suggesting

that primary generators are always to be found in the singular. In

fact, as Rowe points out, it is the reconciling and resolving of two

or more such ideas which characterises design protocols. However,

we must leave further discussion of this complication, and of the

rejecting or resolving of primary generators, until a later chapter.

In summary

This chapter has examined the design process as a sequence of

activities and found the idea rather unconvincing. Certainly it is

reasonable to argue that for design to take place a number of

things must happen. Usually there must be a brief assembled, the

designer must study and understand the requirements, produce

one or more solutions, test them against some explicit or implicit

criteria, and communicate the design to clients and constructors.

The idea, however, that these activities occur in that order, or

even that they are identifiable separate events seems very ques-

tionable. It seems more likely that design is a process in which

problem and solution emerge together. Often the problem may

not even be fully understood without some acceptable solution

to illustrate it. In fact, clients often find it easier to describe their

problems by referring to existing solutions which they know of.

This is all very confusing, but it remains one of the many charac-

teristics of design that it so challenging and interesting to do and

study.

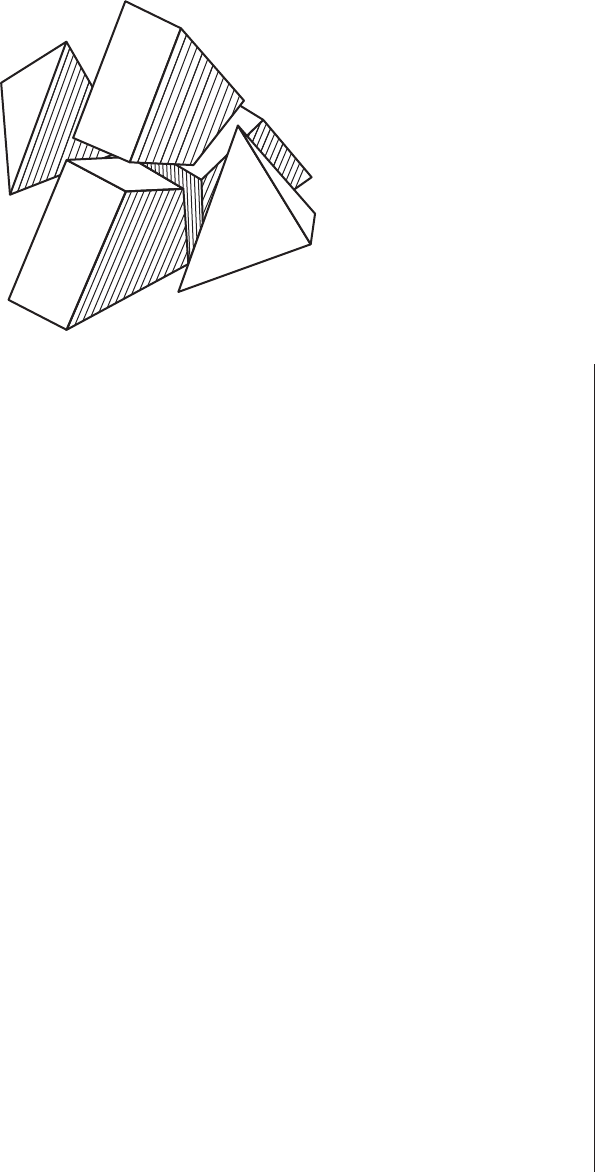

Our final attempt at a map of the design process shows this

negotiation between problem and solution with each seen as a

reflection of the other (Fig. 3.7). The activities of analysis, synthesis

and evaluation are certainly involved in this negotiation but the

map does not indicate any starting and finishing points or the

direction of flow from one activity to another. However, this map

should not be read too literally since any visually understandable

HOW DESIGNERS THINK

48

H6077-Ch03 9/7/05 12:26 PM Page 48

diagram is probably far too much of a simplification of what is

clearly a highly complex mental process.

In the next section of this book we explore the nature of design

problems and their solutions in order to get a better understanding

of just why designers think the way they do.

References

Akin, O. (1986). Psychology of architectural design. London, Pion.

Archer, L. B. (1969). The structure of the design process. Design Methods

in Architecture. London, Lund Humphries.

Asimow, M. (1962). Introduction to Design. Englewood Cliffs, Prentice Hall.

Darke, J. (1978). The primary generator and the design process. New

Directions in Environmental Design Research: procedings of EDRA 9.

Washington, EDRA. 325–337.

Eastman, C. M. (1970). On the analysis of the intuitive design process.

Emerging Methods in Environmental Design and Planning. Cambridge

Mass, MIT Press.

Gregory, S. A. (1966). The Design Method. London, Butterworths.

Hillier, B., Musgrove, J. et al. (1972). Knowledge and design. Environ-

mental Design: research and practice EDRA 3. University of California.

Jones, J. C. (1966). Design methods reviewed. The Design Method.

London, Butterworths.

Jones, J. C. (1970). Design Methods: seeds of human futures. New York,

John Wiley.

Lawson, B. R. (1972). Problem Solving in Architectural Design. University of

Aston in Birmingham.

Lawson, B. R. (1979b). “Cognitive strategies in architectural design.”

Ergonomics 22(1): 59–68.

Lawson, B. R. (1994b). Design in Mind. Oxford, Butterworth Architecture.

Levin, P. H. (1966). “The design process in planning.” Town Planning

Review 37(1).

ROUTE MAPS OF THE DESIGN PROCESS

49

SOLUTION

PROBLEM

synthesis

evaluation

analysis

Figure 3.7

The design process seen as a

negotiation between problem

and solution through the three

activities of analysis, synthesis

and evaluation

H6077-Ch03 9/7/05 12:26 PM Page 49

Markus, T. A. (1969b). The role of building performance measurement and

appraisal in design method. Design methods in Architecture. London,

Lund Humphries.

Matchett, E. (1968). “Control of thought in creative work.” Chartered

Mechanical Engineer 14(4).

Maver, T. W. (1970). Appraisal in the building design process. Emerging

Methods in Environmental Design and Planning. Cambridge Mass,

MIT Press.

Page, J. K. (1963). Review of the papers presented at the conference.

Conference on Design Methods. Oxford, Pergamon.

Rosenstein, A. B., Rathbone, R. R. et al. (1964). Engineering Communica-

tions. Englewood Cliffs, Prentice Hall.

Rowe, P. G. (1987). Design Thinking. Cambridge Mass, MIT Press.

HOW DESIGNERS THINK

50

H6077-Ch03 9/7/05 12:26 PM Page 50

PART TWO

PROBLEMS AND

SOLUTIONS

H6077-Ch04 9/7/05 12:26 PM Page 51

This Page is Intentionally Left Blank

4

The components

of design problems

It seemed that the next minute they would discover a solution. Yet it

was clear to both of them that the end was still far, far off, and that

the hardest and most complicated part was only just beginning.

Anton Chekhov, The Lady with the Dog

It has long been an axiom of mine that the little things are infinitely

the most important.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes

Above and below the problem

Designers are traditionally identified not so much by the kinds of

problems they tackle as by the kinds of solutions they produce. Thus

industrial designers are so called because they create products for

industrial and commercial organisations whereas interior designers

are expected to create interior spaces. Of course, reality is not actu-

ally quite so rigid as this. Many designers dabble in other fields,

some quite regularly, but most designers tend not to be quite so

versatile as some writers on design methodology appear to think.

We have already seen that this is to some extent the result of

the range of technologies understood by the designer. Architects

for example need to understand, amongst a great deal else, the

structural properties and jointing problems associated with timber. It

seems likely, then, that most architects could turn furniture designer

to design a wooden chair, although a furniture designer would prob-

ably claim to be able to recognise architect-designed chairs. This is

because most architects are used to handling timber at a different

scale and in a different context and thus have already developed a

‘timber language’ with a distinctly architectural accent. The imposed

loads and methods of construction of buildings are rather different

H6077-Ch04 9/7/05 12:26 PM Page 53

to those found in furniture. While timber is capable of solving both

problems there are many other materials, each with their own tech-

nology, which are not usually common to architecture and furniture

design. Although both are possible, we do not very often see brick

chairs or polypropylene buildings!

The various design fields are also often thought to be different in

terms of the inherent difficulty of the problems they present. It is

easy to assume that size represents complexity. This argument sug-

gests that architecture must be more complex than industrial design

since buildings are larger than products. Certainly it is possible to

see the three-dimensional design fields in a tree with town planning

at the roots and the trunk beginning to branch out through urban

design, architecture and interior design to the twigs of industrial

design, but does this really mean that town planning is more diffi-

cult than product design? (Fig. 4.1).

Difficulty is, of course, a subjective matter. What one person finds

difficult may often be easy to another, so we must look at the exact

nature of these various kinds of problems to discover more. Urban

design solutions are obviously much larger in scale than architectural

solutions, but are urban design problems also in some way bigger

and more complex than architectural problems? The answer to this

question must be that this is not necessarily so. What really matters

HOW DESIGNERS THINK

54

product design

interior design

architecture

urban design

town planning

Figure 4.1

A ‘tree’ of three dimensional

design fields

H6077-Ch04 9/7/05 12:26 PM Page 54

here is just how far down the hierarchy the designer must go. For

example, when designing an ordinary house architects are unlikely

to be greatly concerned with detailed considerations of methods of

opening and closing cupboard doors. There may be some thought

necessary as to whether the windows might be of the sliding sash,

hinged casement or pivoting variety; but even that is not usually crit-

ical. The designer of a small caravan or boat, however, may need to

give very careful thought to such matters. Even the way in which

cupboard doors open in the restricted space available may be of

crucial significance. Thus part of the definition of a design problem is

the level of detail which requires attention. What usually seems

detail to architects may be central to interior or industrial designers

and so on.

The beginning and end of the problem

How, then, do we find the end of a design problem? Is it not pos-

sible to go on getting involved in more and more detail? Indeed

this is so; there is no natural end to the design process. There is

no way of deciding beyond doubt when a design problem has

been solved. Designers simply stop designing either when they

run out of time or when, in their judgement, it is not worth pursu-

ing the matter further. In design, rather like art, one of the skills is

in knowing when to stop. Unfortunately, there seems to be no

real substitute for experience in developing this judgement. This

presents considerable difficulties not just for students of design,

but also for practitioners. Since there is no real end to a design

problem it is very hard to decide how much time should be

allowed for its solution. Generally speaking, it seems that the

nearer you get to finishing a design the more accurately you are

able to estimate how much work remains to be done. As we have

seen in the last section we learn about design problems largely

by trying to solve them. Thus it may take quite a lot of effort

before a designer is really aware just how difficult a problem is.

First impressions are rarely very reliable in these matters. Design

students seem to be incorrigibly optimistic in their estimation of

the difficulty of problems and the time needed to arrive at

acceptable solutions. As a result students often fail to get down

to the level of detail required of them by their tutors. It is all too

easy to look superficially at a new design problem and, failing to

see any great difficulty, imagine that there is no real urgency.

THE COMPONENTS OF DESIGN PROBLEMS

55

H6077-Ch04 9/7/05 12:26 PM Page 55

Only later, perhaps when it is too late, do the difficulties emerge

in response to some effort.

One of the essential characteristics of design problems then is

that they are often not apparent but must be found. Unlike cross-

word puzzles, brain-teasers or mathematical problems, neither the

goal nor the obstacle to achieving that goal are clearly expressed.

In fact, the initial expression of design problems may often be

quite misleading. If design problems are characteristically unclearly

stated, then it is also true that designers seem never to be satisfied

with the problem as presented. Eberhard (1970) has amusingly

illustrated this sometimes infuriating habit of designers with his

cautionary tale of the doorknob. He suggests that there are two

ways in which designers can retreat back up the hierarchy of prob-

lems, by escalation and by regression.

When faced with the task of designing a new knob for his client’s

office door, Eberhard’s designer suggests that perhaps ‘we ought

to ask ourselves whether a doorknob is the best way of opening

and closing a door’. Soon the designer is questioning whether the

office really needs a door, or should even have four walls and so

on. As Eberhard reports from his own experience, such a train of

argument can lead to the redesign of the organisation of which the

client and his office are part, and ultimately the very political sys-

tem which allows this organisation to exist is called into question.

This escalation leads to an ever wider definition of the problem.

Rather like the after-image in your eye after looking at a bright

light, the problem seems to follow your gaze.

We may also respond to a design problem by what Eberhard

calls regression. A student of mine who was asked to design a new

central library building decided that he needed to study the vari-

ous methods of loaning and storing books. As his design tutor

I agreed that this seemed sensible, only to discover at the next

tutorial that his work now looked more as if he was preparing for a

degree in librarianship than one in architecture. This trail of regres-

sion is to a certain extent encouraged by some of the maps of the

design process which were reviewed in Chapter 3. This behaviour

is only one logical outcome in practice of the notion that analysis

precedes synthesis and data collection precedes analysis. As

we have seen, in design it is difficult to know what problems

are relevant and what information will be useful until a solution is

attempted.

Both escalation and regression often go together. Thus my archi-

tectural student studying librarianship may also become convinced

that a new central library building is no answer. The problem, he

HOW DESIGNERS THINK

56

H6077-Ch04 9/7/05 12:26 PM Page 56

may argue, lies in designing a new system of making books more

available by providing branch libraries, travelling libraries or per-

haps even using new methods of data transmission by television.

While this continuous broadening of the problem can be used to

avoid the issue and put off the evil day of actually getting to grips

with the design, nevertheless it does represent a sensibly cautious

response to unclearly stated problems. Design action, like medi-

cine, is only needed when the current situation is in some way

unsatisfactory, but which is better, to treat the symptoms or to look

for the cause?

The design fix

A client once asked me to design an extension to his house. The

initial brief was rather vague with various ideas of adding an extra

bedroom or a study. The real purpose of this extension was difficult

to understand since the house was already large enough for all the

family to have their own bedrooms and still leave a room which could

have been used as a study. The site was cramped and any extension

had to either occupy some valued garden space or involve consider-

able expense in building over a single storey garage and removing a

rather splendid pitched roof. It seemed that any extension was

almost bound to create new problems, and was not even likely to

prove a worthwhile investment. The client’s thinking was still unclear

and at one meeting, ideas of being able to accommodate grand-

parents were being discussed to the sounds of rather loud music

from one of the teenage children’s bedrooms. It then gradually

emerged that this was the real source of the problem. In fact the

house was indeed already large enough but not well enough divided

up acoustically. The problem then shifted to installing some better

sound insulation, but this is by no means easy to achieve with exist-

ing traditional domestic construction. I suggested the actual solution

initially as a joke. Buy the children some headphones! Thus by treat-

ing the cause of the problem rather than fixing the symptoms the

client kept his garden and his money. I regrettably lost some fees,

but gained a very grateful client who remained a friend. This presents

a rather unglamorous view of design problems. The stereotypical

public image of design portrays the creation of new, original and

uncompromising objects or environments.

The reality is that design is often more of a repair job. Part of the

problem is in correcting something which has gone wrong in some

THE COMPONENTS OF DESIGN PROBLEMS

57

H6077-Ch04 9/7/05 12:26 PM Page 57