Henslin James M. Sociology: A Down to Earth Approach

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

in a moment of anger, and my hands accidentally wrapped around my daughter’s wind-

pipe” (LeDuff 2003).

Marital or Intimacy Rape. Sociologists have found that marital rape is more common

than is usually supposed. For example, between one-third and one-half of women who

seek help at shelters for battered women are victims of marital rape (Bergen 1996).

Women at shelters, however, are not representative of U.S. women. To get a better an-

swer of how common marital rape is, sociologist Diana Russell (1990) used a sampling

Two Sides of Family Life 491

“Why Doesn’t She Just Leave?”

The Dilemma of Abused Women

“Why would she ever put up with violence?” is a ques-

tion on everyone’s mind. From the outside, it looks so

easy. Just pack up and leave.“I know I wouldn’t put up

with anything like that.”

Yet this is not what typically happens. Women tend

to stay with their men after they are abused. Some stay

only a short while, to be sure, but others remain in abu-

sive situations for years.Why?

Sociologist Ann Goetting (2001) asked this question,

too. To learn the answer, she interviewed women who

had made the break. She wanted to find out what it was

that set them apart. How were they able to leave, when

so many women couldn’t seem to? She found that

1. They had a positive self-image.

Simply put, they believed that they deserved better.

2. They broke with old ideas.

They did not believe that a wife had to stay with her

husband no matter what.

3. They found adequate finances.

For some, this was easy. But others had to save for

years, putting away just a dollar or two a week.

4. They had supportive family and friends.

A support network served as a source of

encouragement to help them rescue themselves.

If you take the opposite of these four characteristics,

you can understand why some women put up with abuse:

They don’t think they deserve anything better, they believe

it is their duty to stay, they don’t think they can make it

financially, and they lack a supportive network.These four

factors are not of equal importance to all women, of

course. For some, the lack of finances is the most im-

portant, while for others, it is their low self-concept.The

lack of a supportive network is also significant.

There are two additional factors: The woman must

define her husband’s acts as abuse that warrants her

leaving, and she must decide that he is not going to

change. If she defines her husband’s acts as normal, or

perhaps as deserved in some way, she does not have a

motive to leave. If she defines his acts as temporary,

thinking that her husband will change, she is likely to

stick around to try to change her husband.

Sociologist Kathleen Ferraro (2006) reports that when

she was a graduate student, her husband “monitored my

movements, eating, clothing, friends, money, make-up, and

language. If I challenged his commands, he slapped or

kicked me or pushed me down.” Ferraro was able to leave

only after she defined her husband’s acts as intolerable

abuse—not simply that she was caught up in an unappeal-

ing situation that she had to put up with—and after she

decided that her husband was not going to change. Fellow

students formed the supportive network that Ferraro

needed to act on her new definition. Her graduate men-

tor even hid her from her husband after she left him.

For Your Consideration

On the basis of these findings, what would you say to a

woman whose husband is abusing her? How do you

think battered women’s shelters fit into this explana-

tion? What other parts of this puzzle can you think of—

such as the role of love?

Down-to-Earth Sociology

Spouse abuse is one of the most common forms of

violence. Shown here are police pulling a woman

from her bathroom window, where she had fled from

her husband, who was threatening to shoot her.

technique that allows generalization, but only to San Francisco. She found that 14 per-

cent of married women report that their husbands have raped them. Similarly, 10 per-

cent of a representative sample of Boston women interviewed by sociologists David

Finkelhor and Kersti Yllo (1985, 1989) reported that their husbands had used physical

force to compel them to have sex. Compared with victims of rape by strangers or ac-

quaintances, victims of marital rape are less likely to report the rape (Mahoney 1999).

With the huge numbers of couples who are cohabiting, we need a term that includes

sexual assault in these relationships. Perhaps, then, we should use the term intimacy rape.

And intimacy rape is not limited to men who sexually assault women. Sociologist Lori

Girshick (2002) interviewed lesbians who had been sexually assaulted by their partners.

In these cases, both the victim and the offender were women. Girshick points out that if

the pronoun “he” were substituted for “she” in her interviews, a reader would believe that

the events were being told by women who had been battered and raped by their hus-

bands. Like wives who have been raped by their husbands, these victims, too, suffered

from shock, depression, and self-blame.

Incest. Sexual relations between certain relatives (for example, between brothers and

sisters or between parents and children) constitute incest. Incest is most likely to occur

in families that are socially isolated (Smith 1992). Sociologist Diana Russell (n.d.)

found that incest victims who experience the greatest trauma are those who were vic-

timized the most often, whose assaults occurred over longer periods of time, and whose

incest was “more intrusive”—for example, sexual intercourse as opposed to sexual

touching.

Who are the offenders? The most common incest is apparently between brothers and

sisters, with the sex initiated by the brother (Canavan et al. 1992; Carlson et al. 2006).

With no random samples, however, we don’t know for sure. Russell found that uncles are

the most common offenders, followed by first cousins, stepfathers, brothers, and, finally,

other relatives ranging from brothers-in-law to stepgrandfathers. All studies indicate that

incest between mothers and their children is rare, more so than between fathers and their

children.

The Bright Side of Family Life: Successful Marriages

Successful Marriages. After examining divorce and family abuse, one could easily con-

clude that marriages seldom work out. This would be far from the truth, however, for

about three of every five married Americans report that they are “very happy” with their

marriages (Whitehead and Popenoe 2004). (Keep in mind that each year divorce elimi-

nates about a million unhappy marriages.) To find out what makes marriage successful,

sociologists Jeanette and Robert Lauer (1992) interviewed 351 couples who had been

married fifteen years or longer. Fifty-one of these marriages were unhappy, but the cou-

ples stayed together for religious reasons, because of family tradition, or “for the sake of

the children.”

Of the others, the 300 happy couples, all

1. Think of their spouse as their best friend

2. Like their spouse as a person

3. Think of marriage as a long-term commitment

4. Believe that marriage is sacred

5. Agree with their spouse on aims and goals

6. Believe that their spouse has grown more interesting over the years

7. Strongly want the relationship to succeed

8. Laugh together

Sociologist Nicholas Stinnett (1992) used interviews and questionnaires to study 660

families from all regions of the United States and parts of South America. He found that

happy families

492 Chapter 16 MARRIAGE AND FAMILY

incest sexual relations be-

tween specified relatives, such

as brothers and sisters or par-

ents and children

1. Spend a lot of time together

2. Are quick to express appreciation

3. Are committed to promoting one another’s welfare

4. Do a lot of talking and listening to one another

5. Are religious

6. Deal with crises in a positive manner

There are three more important factors: Marriages are happier when the partners get

along with their in-laws (Bryant et al. 2001), find leisure activities that they both enjoy

(Crawford et al. 2002), and agree on how to spend money (Bernard 2008).

Symbolic Interactionism and the Misuse of Statistics

Many students express concerns about their own marital future, a wariness born out

of the divorce of their parents, friends, neighbors, relatives—even their pastors and

rabbis. They wonder about their chances of having a successful marriage. Because so-

ciology is not just about abstract ideas, but is really about our lives, it is important to

stress that you are an individual, not a statistic. That is, if the divorce rate were 33

percent or 50 percent, this would not mean that if you marry, your chances of getting

divorced are 33 percent or 50 percent. That is a misuse of statistics—and a common

one at that. Divorce statistics represent all marriages and have absolutely nothing to do

with any individual marriage. Our own chances depend on our own situations—

especially the way we approach marriage.

To make this point clearer, let’s apply symbolic interactionism. From a symbolic inter-

actionist perspective, we create our own worlds. That is, because our experiences don’t

come with built-in meanings, we interpret our experiences and act accordingly. As we do

so, we can create a self-fulfilling prophecy. For example, if we think that our marriage

might fail, we are more likely to run when things become difficult. If we think that our

marriage is going to work out, we are more likely to stick around and to do things to

make the marriage successful. The folk saying “There are no guarantees in life” is cer-

tainly true, but it does help to have a vision that a good marriage is possible and that it is

worth the effort to achieve.

The Future of Marriage and Family

What can we expect of marriage and family in the future? Despite its many problems, mar-

riage is in no danger of becoming a relic of the past. Marriage is so functional that it ex-

ists in every society. Consequently, the vast majority of Americans will continue to find

marriage vital to their welfare.

Certain trends are firmly in place. Cohabitation, births to single women, age at first

marriage, and parenting by grandparents will increase. As more married women join the

workforce, wives will continue to gain marital power. The number of elderly will increase,

and more couples will find themselves sandwiched between caring for their parents and

rearing their own children.

Our culture will continue to be haunted by distorted images of marriage and family:

the bleak ones portrayed in the mass media and the rosy ones perpetuated by cultural

myths. Sociological research can help to correct these distortions and allow us to see how

our own family experiences fit into the patterns of our culture. Sociological research can

also help to answer the big question: How do we formulate social policies that will sup-

port and enhance family life?

The Future of Marriage and Family 493

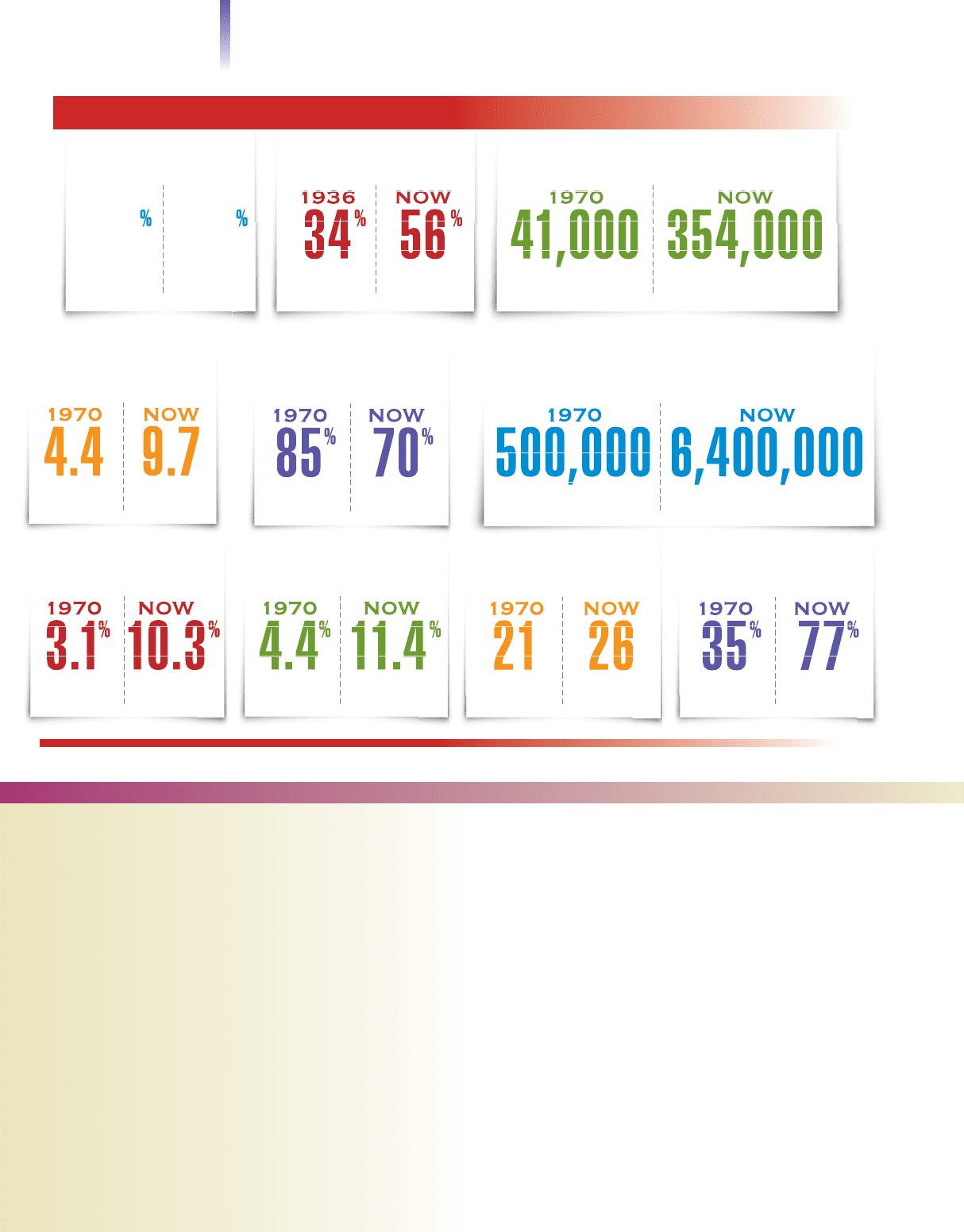

Percentage of white

Americans divorced

1970 NOW

%%

Percentage of African

Americans divorced

1970 NOW

%%

Average age of

rst-time bride

1970 NOW

Af

Number of cohabitating couples

1970

Women ages 20–24

who have never married

W

omen ages

20

–

24

W2024

w

ho have never marrie

d

d

1970 NOW

%%

Percentage of children

under age 18 who live

with both parents

PfAfi

Percentage

of

children

u

nder age 1

8

who live

w

ith both

p

arent

s

1970 NOW

%%

Pfh

Number of hours

per week husbands

do housework

1970 NOW

Number of hour

s

Americans who want

3 or more children

1936

64

NOW

34

%%

Percentage of children

P

Americans who want

0, 1, or 2 children

1936 NOW

%%

Number of marriages with a white

wife and an African American husband

1970 NOW

494 Chapter 16 MARRIAGE AND FAMILY

By the Numbers: Then and Now

SUMMARY and REVIEW

Marriage and Family in Global Perspective

What is a family—and what themes are universal?

Family is difficult to define. There are exceptions to every

element that one might consider essential. Consequently,

family is defined broadly—as people who consider them-

selves related by blood, marriage, or adoption. Universally,

marriage and family are mechanisms for governing mate

selection, reckoning descent, and establishing inheritance

and authority. Pp. 462–464.

Marriage and Family in Theoretical Perspective

What is a functionalist perspective on marriage

and family?

Functionalists examine the functions and dysfunctions of

family life. Examples include the incest taboo and how

weakened family functions increase divorce. Pp. 464–466.

What is a conflict perspective on marriage and family?

Conflict theorists focus on inequality in marriage, espe-

cially unequal power between husbands and wives. P. 466.

What is a symbolic interactionist perspective

on marriage and family?

Symbolic interactionists examine the contrasting experi-

ences and perspectives of men and women in marriage.

They stress that only by grasping the perspectives of

wives and husbands can we understand their behavior.

Pp. 466–468.

The Family Life Cycle

What are the major elements of the family life cycle?

The major elements are love and courtship, marriage,

childbirth, child rearing, and the family in later life. Most

Summary and Review 495

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT Chapter 16

1. Functionalists stress that the family is universal because it

provides basic functions for individuals and society.What

functions does your family provide? Hint: In addition to the

section “The Functionalist Perspective,” also consider the

section “Common Cultural Themes.”

2. Explain why social class is more important than race–

ethnicity in determining a family’s characteristics.

3. Apply this chapter’s contents to your own experience with

marriage and family.What social factors affect your family

life? In what ways is your family life different from that of

your grandparents when they were your age?

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

What can you find in MySocLab? www.mysoclab.com

• Complete Ebook

• Practice Tests and Video and Audio activities

• Mapping and Data Analysis exercises

• Sociology in the News

• Classic Readings in Sociology

• Research and Writing advice

mate selection follows predictable patterns of age, social

class, race–ethnicity, and religion. Child-rearing patterns

vary by social class. Pp. 468–474.

Diversity in U.S. Families

How significant is race–ethnicity in family life?

The primary distinction is social class, not race–ethnicity.

Families of the same social class are likely to be similar, re-

gardless of their race–ethnicity. Pp. 474–478.

What other diversity do we see in

U.S. families?

Also discussed are one-parent, childless, blended, and

gay and lesbian families. Each has its unique character-

istics, but social class is significant in determining their

primary characteristics. Poverty is especially significant

for single-parent families, most of which are headed by

women.Pp. 478–480.

Trends in U.S. Families

What major changes characterize U.S. families?

Three changes are postponement of first marriage, an in-

crease in cohabitation, and more grandparents serving as

parents to their grandchildren. With more people living

longer, many middle-aged couples find themselves sand-

wiched between rearing their children and taking care of

their aging parents. Pp. 480–484.

Divorce and Remarriage

What is the current divorce rate?

Depending on what numbers you choose to compare, you

can produce almost any rate you wish, from 50 percent

to less than 2 percent. P. 484.

How do children and their parents adjust to divorce?

Divorce is difficult for children, whose adjustment prob-

lems often continue into adulthood. Most divorced fathers

do not maintain ongoing relationships with their children.

Financial problems are usually greater for the former wives.

The rate of remarriage has slowed. Pp. 485–489.

Two Sides of Family Life

What are the two sides of family life?

The dark side is abuse—spouse battering, child abuse, mar-

ital rape, and incest. All these are acts that revolve around

the misuse of family power. The bright side is that most peo-

ple find marriage and family to be rewarding. Pp. 490–493.

The Future of Marriage and Family

What is the likely future of marriage and family?

We can expect cohabitation, births to unmarried women, age

at first marriage, and parenting by grandparents to increase.

The growing numbers of women in the workforce are likely

to continue to shift the balance of marital power. P. 493.

Where Can I Read More on This Topic?

Suggested readings for this chapter are listed at the back of this book.

Education

17

Chapter

athy Spiegel was upset. Horace Mann, the

school principal in her hometown in Oregon,

had asked her to come to his office. He explained that

Kathy’s 11-year-old twins had been acting up in class. They were

disturbing other children and the teacher—and what was Kathy going

to do about this?

Kathy didn’t want to tell

Mr. Mann what he could do

with the situation. That

would have gotten her kicked

out of the office. Instead, she

bit her tongue and said she

would talk to her daughters.

* * * * *

On the other side of the country, Jim and Julia Attaway were

pondering their own problem. When they visited their son’s school

in the Bronx, they didn’t like what they saw. The boys looked like

they were junior gang members, and the girls dressed and acted as

though they were sexually active. Their own 13-year-old son had

started using street language at home, and it was becoming

increasingly difficult to communicate with him.

* * * * *

In Minneapolis, Denzil and Tamika Jefferson were facing a

much quieter crisis. They found life frantic as they hurried from

one school activity to another. Their 13-year-old son attended a

private school, and the demands were so intense that it felt like

the junior year in high school. They no longer seemed to have any

relaxed family time together.

* * * * *

In Atlanta, Jaime and Maria Morelos were upset at the ideas

that their 8-year-old daughter had begun to express at home.

As devout first-generation Protestants, Jaime and Maria felt

moral issues were a top priority, and they didn’t like what they

were hearing.

* * * * *

Kathy talked the matter over with her husband, Bob. Jim and

Julia discussed their problem, as did Denzil and Tamika and Jaime

and Maria. They all came to the same conclusion: The problem

was not their children. The problem was the school their children

attended. All four sets of parents also came to the same solution:

home schooling for their children.

K

Kathy’s 11-year-old twins

were disturbing other

children and the teacher—

and what was Kathy going

to do about this?

497

Mississippi

Home schooling might seem to be a radical solution to today’s education problems, but

it is one that the parents of over a million U.S. children have chosen. We’ll come back to

this topic, but, first, let’s take a broad look at education.

The Development of Modern Education

To provide a background for understanding our own educational system, let’s look first

at education in earlier societies, then trace the development of universal education.

Education in Earlier Societies

Earlier societies had no separate social institution called education. They had no special

buildings called schools and no people who earned their living as teachers. Rather, as an

ordinary part of growing up, children learned what was necessary to get along in life. If

hunting or cooking were the essential skills, then parents and other relatives taught them

to the children. Education was synonymous with acculturation, learning a culture. It still is

in today’s tribal groups.

In some societies—such as China, Greece, and North Africa—when a sufficient sur-

plus developed, a separate institution for education appeared. Some people then devoted

themselves to teaching, while those who had the leisure—the children of the wealthy—

became their students. In ancient China, for example, Confucius taught a few select

pupils, while in Greece, Aristotle, Plato, and Socrates taught science and philosophy to

upper-class boys. Education, then, came to be something distinct from informal accultur-

ation. Education is a group’s formal system of teaching knowledge, values, and skills.

Such instruction stood in marked contrast to the learning of traditional skills such as

farming or hunting, for it was intended to develop the mind. Education flourished dur-

ing the period roughly marked by the birth of Christ, then slowly died out. During the

Dark Ages of Europe, monks kept the candle of enlightenment burning. Except for a

handful of the wealthy and some members of the nobility, only the monks could read

and write. Although the monks delved into philosophy, they focused on learning Greek,

Latin, and Hebrew so that they could study the Bible and writings of early church lead-

ers. The Jews also kept formal learning alive as they studied the Torah. In the Arab world,

the center of learning was Baghdad, where the focus was on the Koran, poetry, philoso-

phy, linguistics, and astronomy.

Formal education remained limited to

those who had the leisure to pursue it. (The

word school comes from the Greek word

scholé meaning “leisure.”) Industrialization

transformed education, for some of the ma-

chinery and new types of jobs required

workers to read, write, and work accurately

with numbers—the classic three R’s of the

nineteenth century (Reading, ‘Riting, and

‘Rithmetic).

Industrialization and

Universal Education

After the American Revolution, the founders

of the new republic were concerned that the

many contrasting religious and ethnic

groups (nationalities) would make the na-

tion unstable. To help create a uniform na-

tional culture, Thomas Jefferson and Noah

Webster proposed universal schooling. Stan-

dardized texts would instill patriotism and

498 Chapter 17 EDUCATION

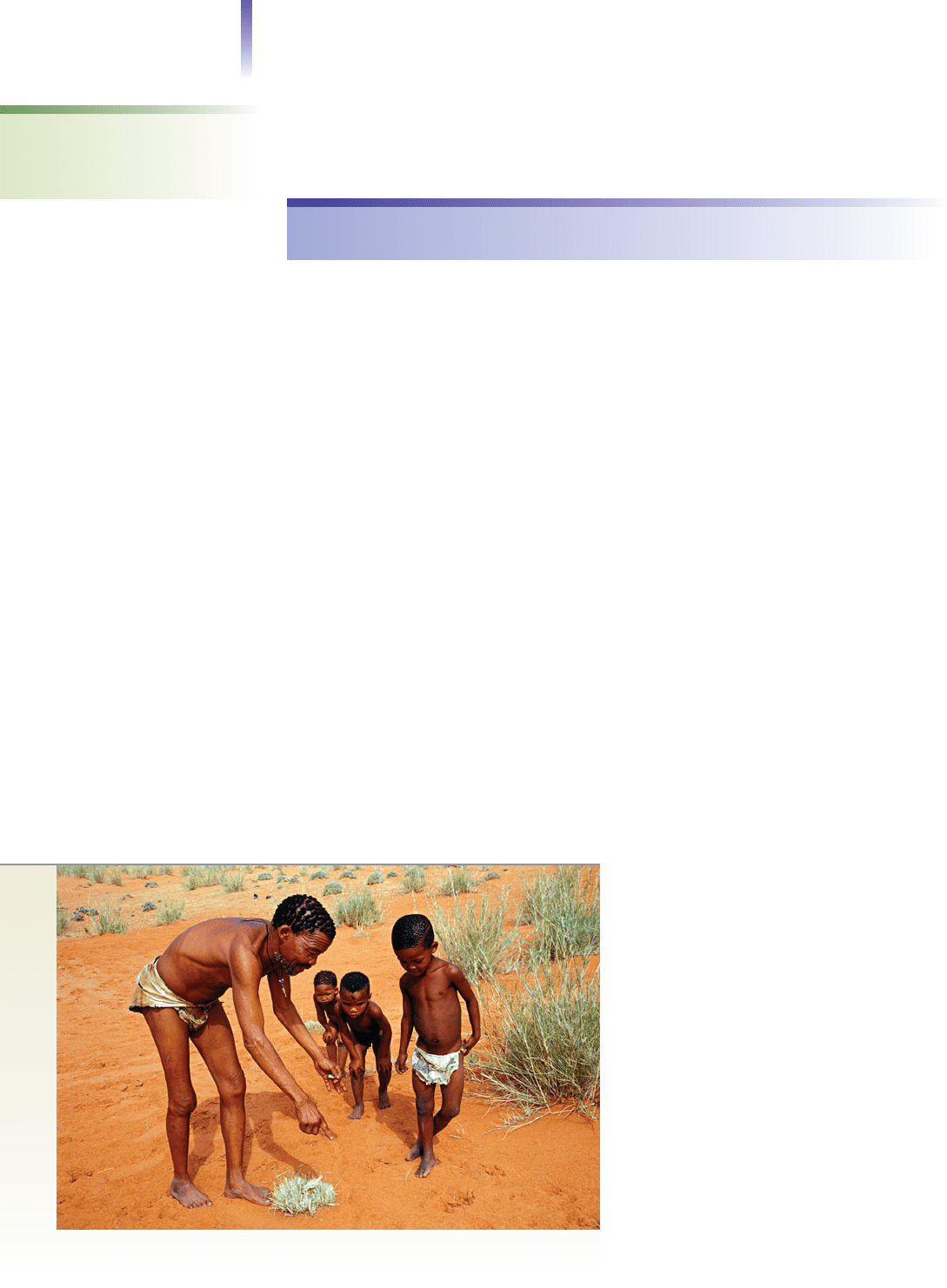

In hunting and gathering societies, there is no separate social institution called education.

Instead, children learn from their parents and elders. These boys in South Africa are

learning survival skills as their grandfather shows them lizard tracks in the sand.

education a formal

system of teaching knowledge,

values, and skills

teach the principles of representative govern-

ment (Hellinger and Judd 1991). If this new

political experiment were to succeed, they

reasoned, it would need educated citizens

who were capable of making sound decisions

and voting wisely. A national culture re-

mained elusive, however, and the country re-

mained politically fragmented into the

1800s. Many states even considered them-

selves to be near-sovereign nations.

Education reflected this disunity. There

was no comprehensive school system, just a

hodgepodge of independent schools. Public

schools even charged tuition. Lutherans,

Presbyterians, and Roman Catholics oper-

ated their own schools (Hellinger and Judd

1991). Children of the rich attended pri-

vate schools. Children of the poor received

no formal education—nor did slaves. High

school was considered higher education

(hence the name high school), and only the

wealthy could afford it. College, too, was

beyond the reach of almost everyone.

Horace Mann, an educator from Massa-

chusetts, found it deplorable that parents with an average income could not afford to send

their children to grade school. In 1837 he proposed that “common schools,” supported

through taxes, be established throughout his state. Mann’s idea spread, and state after state

began to provide free public education. It is no coincidence that universal education and in-

dustrialization occurred at the same time. As they observed the transformation of the econ-

omy, political and civic leaders recognized the need for an educated workforce. They also

feared the influx of “foreign” values and, like the founders of the country, looked on public

education as a way to “Americanize” immigrants (Hellinger and Judd 1991).

By 1918, all U.S. states had mandatory education laws requiring children to attend

school, usually until they completed the eighth grade or turned 16, whichever came first. By

this time, schooling had become widespread, and graduation from the eighth grade marked

the end of education for most people. “Dropouts” at that time were students who did not

complete grade school.

As industrialization progressed

and fewer people made their living

from farming, even more years of

formal education came to be re-

garded as essential to the well-

being of society. As graduation

from high school became more

common, more students wanted a

college education. Free education

stopped with high school, how-

ever, and with the distance to the

nearest college too far and the cost

of tuition and lodging too great,

most high school graduates were

unable to attend college. As is dis-

cussed in the Down-to-Earth

Sociology box on the next page,

this predicament gave birth to

community colleges. Figure 17.1

shows the incredible change in

The Development of Modern Education 499

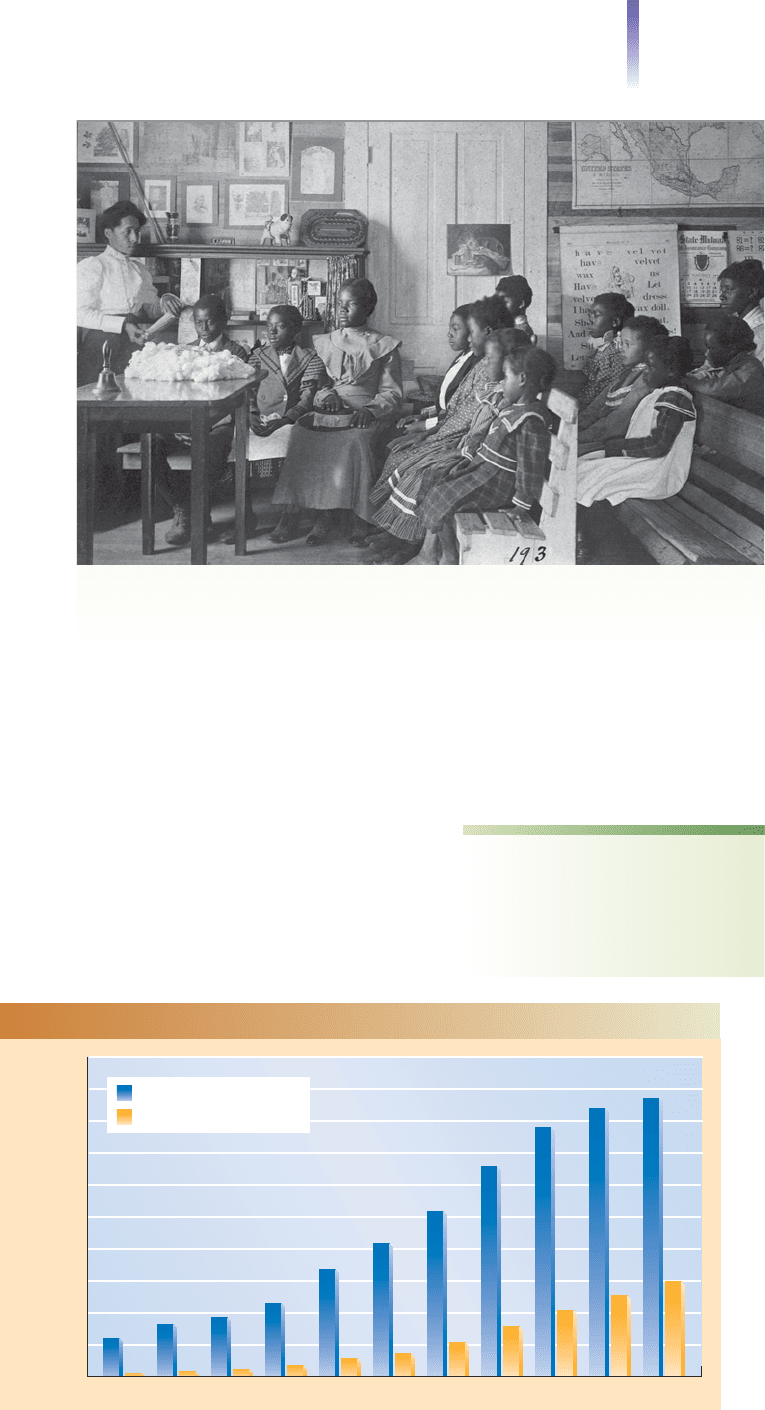

This 1902 photo from Tuskegee, Alabama, provides a glimpse into the past, when free

public education, pioneered in the United States, was still in its infancy. In these one-

room rural schools, a single teacher had charge of grades 1 to 8. Children were

assigned a grade not by age but by mastery of subject matter.

mandatory education laws

laws that require all children to

attend school until a specified

age or until they complete a

minimum grade in school

0%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

70%

80%

90%

Percentage

100%

Year

High school graduates

College graduates

1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010

FIGURE 17.1 Educational Achievement in the United States

Sources: By the author. Based on National Center for Education Statistics 1991:Table 8; Statistical

Abstract of the United States 2011:Table 225.

Note: Americans 25 years and over.

500 Chapter 17 EDUCATION

Community Colleges: Facing

Old and New Challenges

I

attended a junior college in Oakland, California. From

there, with fresh diploma in hand, I transferred to a

senior college—a college in Fort Wayne, Indiana, that

had no freshmen or sophomores.

I didn’t realize that my experimental college matched

the vision of some of the founders of the community

college movement. In the early 1900s, they foresaw a

system of local colleges that would be accessible to the

average high school graduate—a system so extensive that

it would be unnecessary for universities to offer courses

at the freshman and sophomore levels (Manzo 2001).

A group with an equally strong opinion questioned

whether preparing high school graduates for entry to

four-year colleges and universities should be the goal of

junior colleges. They insisted that the purpose of junior

colleges should be vocational preparation, to equip peo-

ple for the job market as electricians and other techni-

cians. In some regions, where the proponents of transfer

dominated, the admissions requirements for junior col-

leges were higher than those of Yale (Pedersen 2001).

This debate was never won by either side, and you can

still hear its echoes today (Van Noy et al. 2008).

The name junior college also became a problem.

Some felt that the word junior made their institution

sound as though it weren’t quite a real college. A strug-

gle to change the name ensued, and several decades ago

community college won out.

The name change didn’t settle the debate about

whether the purpose was preparing students to transfer

to universities or training them for jobs, however. Com-

munity colleges continue to serve this dual purpose.

Community colleges have become such an essential

part of the U.S. educational system that almost two of

every five (36 percent) of all undergraduates in the

United States are enrolled in them (Statistical Abstract

2011:Table 275). They have become the major source of

the nation’s emergency medical technicians, firefighters,

nurses, and police officers. Most students are nontraditional

students: Many are age 25 or older, are from the working

class, have jobs and children, and attend college part-

time (Bryant 2001; Panzarella 2008).

To help students who are not seeking occupational

certificates transfer to four-year colleges and universities,

many community colleges work closely with top-tier pub-

lic and private universities (Chaker 2003b). Some provide

admissions guidance on how to enter flagship state

schools. Others coordinate courses, making sure that they

match the university’s title and numbering system, as well

as its rigor of instruction and grading. More than a third

offer honors programs that prepare talented students to

transfer with ease into these schools (Padgett 2005).

Community colleges face the challenges of securing

adequate budgets in the face of declining resources, ad-

justing to changing job markets, and maintaining quality

instruction. Other challenges include offering effective

remedial courses, meeting the shifting needs of stu-

dents, such as teaching students for whom English is a

second language, and providing on-campus day care for

parents. In their quest to help students complete col-

lege, community colleges are also working to improve

their orientation programs and to find better ways to

monitor their students’ progress (Panzarella 2008).

For Your Consideration

Do you think the primary goal of community colleges

should be to prepare students for jobs or to prepare them

to transfer to four-year colleges and universities? Why?

Down-to-Earth Sociology

Community colleges have opened higher education to

millions of students who would not otherwise have access

to college because of cost or distance.

educational achievement. As you can see, receiving a bachelor’s degree is now twice as

common as completing high school used to be. Two of every three (69 percent) high

school graduates enter college (Statistical Abstract 2011:Table 272).

One of seven Americans has not made it through high school, however, which leads

to economic problems for most of them for the rest of their lives (Statistical Abstract

2011:Table 225). The Social Map on the next page shows how unevenly distributed high

school graduation is among the states. You may want to compare this Social Map with the

one on page 283 that shows how poverty is distributed among the states.