Henslin James M. Sociology: A Down to Earth Approach

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

War and Terrorism: Implementing Political Objectives 451

How Can “Good” People

Torture Others?

W

hen the Nuremberg Trials

revealed the crimes of the

Nazis to the world, people

wondered what kind of abnormal,

bizarre humans could have carried out

those horrific acts.The trials, however,

revealed that the officials who author-

ized the torture and murder of Jews

and the soldiers who followed those

orders were ordinary,“good” people

(Hughes 1962/2005).This revelation

came as a shock to the world.

Later, we learned that in Rwanda

Hutus hacked their Tutsi neighbors to

death. Some Hutu teachers even killed

their Tutsi students. Similar revelations of “good” people

torturing prisoners have come from all over the world—

Cambodia, Iraq, Afghanistan, Mexico.We have also

learned that when the torturers finish their “work,” they

go home to their families, where they are ordinary fa-

thers and husbands.

Let’s try to understand how “good, ordinary people” can

torture prisoners and still feel good about themselves. Con-

sider the four main characteristics of dehumanization

(Bernard et al. 1971):

1. Increased emotional distance from others. People stop iden-

tifying with others, no longer seeing them as having qual-

ities similar to themselves.They perceive them as “the

enemy,” or as objects of some sort. Sometimes they

think of their opponents as less than human, or even not

as people at all.

2. Emphasis on following orders. The individual clothes acts of

brutality in patriotic language: To follow orders is “a sol-

dier’s duty.” Torture is viewed as a tool that helps sol-

diers do their duty. People are likely to say “I don’t like

doing this, but I have to follow orders—and someone

has to do the ‘dirty work.’”

3. Inability to resist pressures. Ideas of morality take a back

seat to fears of losing your job, losing the respect of

peers, or having your integrity and loyalty questioned.

4. A diminished sense of personal responsibility. People come

to see themselves as only small cogs in a large machine.

The higher-ups who give the orders are thought to have

more complete or even secret information that justifies

the torture.The thinking becomes,“Those who make

the decisions are responsible, for they are in a position

to judge what is right and wrong. In my low place in the

system, who am I to question these acts?”

Down-to-Earth Sociology

Sociologist Martha Huggins (2004) interviewed Brazilian

police who used torture to extract confessions. She identi-

fied a fifth method that torturers sometimes use:They

blame the victim. “He was just stupid. If he

had confessed in the first place, he

wouldn’t have been tortured.” This tech-

nique removes the blame from the tor-

turer—who is just doing a job—and

places it on the victim.

A sixth technique of neutralization was

used by U.S. government officials who au-

thorized the torture of terrorists.Their

technique of neutralization was to say that

what they authorized was not torture.

Rather, in their words, they authorized

“enhanced techniques” of interrogation

(Shane 2008).A fair summary of their

many statements on this topic would be

“What we authorized is a harsh, but nec-

essary, method of questioning prisoners,

selectively used on designated individu-

als, to extract information to protect

Americans.” In one of these approved interrogation tech-

niques, called waterboarding, the interrogators would force

a prisoner’s head backward and pour water over his or her

face. The gag reflex would force the prisoner to inhale

water, producing an intense sensation of drowning. When

the interrogators stopped pouring the water, they would

ask their questions again. If they didn’t get a satisfacto-

ryanswer, they continued the procedure. With an outcry

from humanitarian groups and some members of Con-

gress, waterboarding was banned (Shenon 2008).

In several contexts in this book, I have emphasized how

important labels are in social life. Notice how powerful they

are in this situation. Calling waterboarding “not torture”

means that it becomes “not torture”—for those who au-

thorize and practice it. This protects the conscience, allow-

ing the individuals who authorize or practice torture to

retain the sense of a “good” self.

One of my students, a Vietnam veteran, who read this

section, told me,“You missed the major one we used.We

killed kids. Our dehumanizing technique was this saying,

‘The little ones are the soldiers of tomorrow.’”

Such sentiments may be more common than we

suppose—and the killers’ and torturers’ uniforms don’t

have to display swastikas.

For Your Consideration

Do you think you could torture people? Instead of just

saying,“Of course not!” think about this: If “good, ordi-

nary” people can become torturers, why not you? Aren’t

you a “good, ordinary” person? To answer this question

properly, then, let’s rephrase it: Based on what you read

here, what conditions could get you to cooperate in the

torture of prisoners?

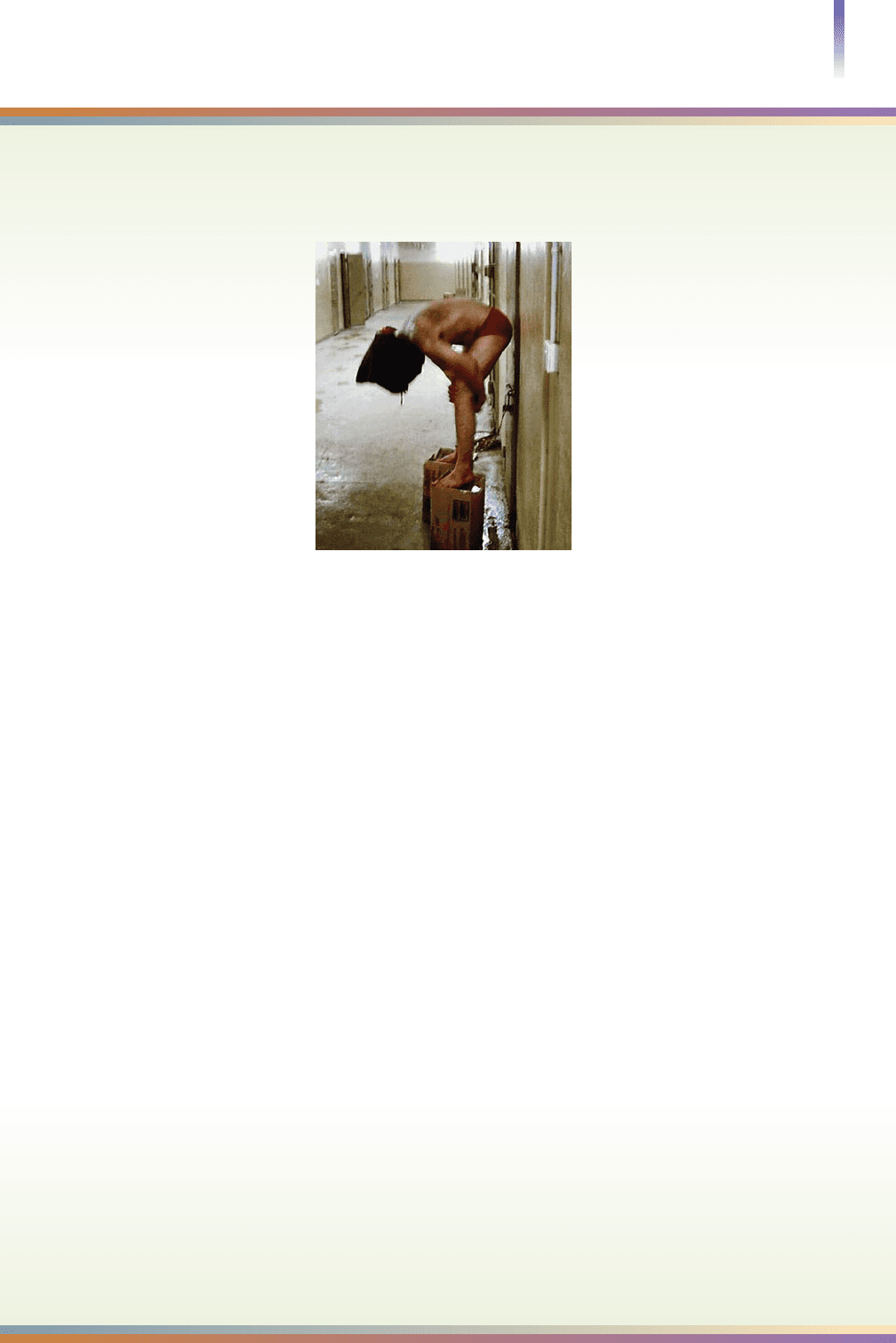

Prisoner at Abu Ghraib Prison, Iraq

Terrorism

Mustafa Jabbar, in Najaf, Iraq, is proud of his first born, a baby boy, but he said, “I will put

mines in the baby and blow him up.” (Sengupta 2004)

How can feelings run so deep that a father would sacrifice his only son? Some groups

nourish hatred, endlessly chronicling the injustices and atrocities of their archenemy.

Stirred in a cauldron of bitterness, antagonism can span generations, its embers some-

times burning for centuries. The combination of perceived injustice and righteous hatred

produces a desire to strike out and hurt an enemy. If a group is weaker than its enemy,

however, what options does it have? Unable to meet its more powerful opponent on the

battlefield, one option is terrorism, violence intended to create fear in order to bring

about political objectives. And, yes, that can mean blowing up your only child. Stronger

groups sometimes use terrorism, too, but this is “just because they can.” They revel in

their power and delight in seeing their opponents suffer.

Suicide terrorism, a weapon sometimes chosen by the weaker group, captures headlines

around the world. Among the groups that have used suicide terrorism are the Palestinians

against the Israelis and the Iraqis against U.S. troops. The suicide terrorism that has had

the most profound effects on our lives is the attack on the World Trade Center and the Pen-

tagon under the direction of Osama bin Laden. What kind of sick people become suicide

terrorists? This is the topic of the Down-to-Earth Sociology box on the next page.

The suicide attacks on New York and Washington are tiny in comparison with the

threat of weapons of mass destruction. If terrorists unleash biological, nuclear, or chem-

ical weapons, the death toll could run in the millions. We’ve had a couple of scares. Crim-

inal opportunists, who don’t care who their customers are, have tried to smuggle enriched

uranium out of Europe. Their shipment was intercepted just before it landed in terrorist

hands (Sheets and Broad 2007a, b). This chilling possibility was brought home to Amer-

icans in 2001 when anthrax powder was mailed to a few select victims.

It is sometimes difficult to tell the difference between war and terrorism. This is espe-

cially so in civil wars when the opposing sides don’t wear uniforms and attack civilians.

Africa is embroiled in such wars. In the Down-to-Earth Sociology box on page 454, we

look at one aspect of these wars, that of child soldiers.

Sowing the Seeds of Future Wars and Terrorism

Selling War Technology. Selling advanced weapons to the Least Industrialized Nations

sows the seeds of future wars and terrorism. When a Least Industrialized Nation buys

high-tech weapons, its neighbors get nervous, which sparks an arms race among them

(Broad and Sanger 2007). Table 15.4 shows that the United States is, by far, the chief

merchant of death. Russia and Great Britain place a distant second and third.

This table also shows the major customers in the business of death. Two matters are

of interest. First, India, where the average annual income is only $600 and Egypt,

where it is only $1,500, are some of the

world’s biggest spenders. Second, the huge

purchase of arms by Saudi Arabia indicates

that U.S. dollars spent on oil tend to return

to the United States. There is, in reality, an ex-

change of arms for oil, with dollars the

medium of exchange. As mentioned in Chap-

ter 9 (page 256), Saudi Arabia cooperates with

the United States by trying to keep oil prices

down and, in return, the United States props

up its dictators.

The seeds of future wars and terrorism are also

sown by nuclear proliferation. Some Least Indus-

trialized Nations, such as India, China, and

North Korea, possess nuclear weapons. So does

Pakistan, whose head of nuclear development

452 Chapter 15 POLITICS

terrorism the use of vio-

lence or the threat of violence

to produce fear in order to at-

tain political objectives

The Top Arms Sellers The Top Arms Buyers

1. $28 billion, United States 1. $19 billion, Saudi Arabia

2. $16 billion, Russia 2. $9 billion, China

3. $12 billion, Great Britain 3. $7 billion, United Arab Emirates

4. $9 billion, France 4. $6 billion, Egypt

5. $3 billion, China 5. $6 billion, India

6. $2 billion, Israel 6. $4 billion, Israel

7. $1 billion, Germany 7. $4 billion,Taiwan

8. $1 billion, Ukraine 8. $3 billion, South Korea

Note: For years 2001–2004.

TABLE 15.4 The Business of Death

Source: By the author. Based on Grimmett 2005:Tables 2F, 2I.

War and Terrorism: Implementing Political Objectives 453

Who Are the Suicide Terrorists?

Testing Your Stereotypes

W

e carry a lot of untested ideas around in our

heads, and we use those ideas to make sense

out of our experiences.When something hap-

pens, we place the event into a mental file of “similar

events,” which gives us a way of interpreting it.This is a

normal process, and all of us do it all the time.Without

stereotypes—ideas of what people, things, and events are

like—we could not get through everyday life.

As we traverse society, our files of “similar people” and

“similar events” usually provide adequate interpretations.

That is, the explanations we get from our interpreting

process usually satisfy our “need to understand.” Some-

times, however, our files for classifying people and events

leave us perplexed, not knowing what to make of things. For

most of us, terrorism is like this. We don’t know any terror-

ists or suicide bombers, so it is hard to imagine someone

becoming one.

Let’s see if we can flesh out those mental files a bit.

Sociologist Marc Sageman (2008a, 2008b) wondered

about terrorists, too. Finding that his mental files were

inadequate to understand them, he decided that research

might provide the answer. Sageman had an unusual

advantage for gaining access to data—he had been in the

CIA.Through his contacts, he studied 400 al-Qaeda terror-

ists who had targeted the United States. He was able to

examine thousands of pages of their trial records.

So let’s use Sageman’s research to test some common

ideas. I think you’ll find that the data blow away stereo-

types of terrorists.

• Here’s a common stereotype. Terrorists come from

backgrounds of poverty. Cunning leaders take advan-

tage of their frustration and direct it toward striking

out at an enemy. Not true. Three-quarters of the ter-

rorists came from the middle and upper classes.

• How about this image, then—the deranged loner? We

carry around images like this concerning serial and

mass murderers. It is a sort of catch-all stereotype that

we have.These people can’t get along with anyone; they

stew in their loneliness and misery; and all this bubbles

up in misapplied violence. You know, the workplace

killer sort of image, loners “going postal.” Not this one,

either. Sageman found that 90 percent of the terrorists

came from caring, intact families. On top of this, 73 per-

cent were married, and most of them had children.

• Let’s try another one. Terrorists are ignorant people, so

those cunning leaders can manipulate them easily. We

have to drop this one, too. Sageman found that 63

percent of the terrorists had gone to college.Three-

quarters worked in professional and semi-professional

occupations. Many were scientists, engineers, and

architects.

What? Most terrorists are intelligent, educated, family-

oriented, professional people? How can this be? Sageman

found that these people had gone through a process of

radicalization. Here was the trajectory:

1. Moral outrage. They became incensed about something

that they felt was terribly wrong.

2. Ideology. They interpreted their moral outrage within a

radical, militant interpretation of Islamic teachings.

3. Shared outrage and ideology. They found like-minded

people, often on the Internet, especially in chat rooms.

4. Group decision: They decided that an act of terrorism

was called for.

To understand terrorists, then, it is not the individual

that we need to look at.We need to focus on group

dynamics, how the group influences the individual and

how the individual influences the group (as we studied in

Chapter 6). In one sense, however, the image of the loner

does come close. Seventy percent of these terrorists

committed themselves to extreme acts while they were

living away from the country where they grew up.They

became homesick, sought out people like themselves,

and ended up at radical mosques where they learned a

militant script.

Constantly, then, sociologists seek to understand the

relationship between the individual and the group.This fas-

cinating endeavor sometimes blows away stereotypes.

For Your Consideration

1. How do you think we can reduce the process of radi-

calization that turns people into terrorists?

2. Sageman concludes that this process of radicalization

has produced networks of homegrown, leaderless ter-

rorists, ones that don’t need al-Qaeda to direct them.

He also concludes that this process will eventually

wear itself out. Do you agree? Why or why not?

Down-to-Earth Sociology

What does a suicide

bomber look like? Iraqi

police arrested this girl,

who was wearing an

explosives vest.

454 Chapter 15 POLITICS

Child Soldiers

W

hen rebels entered 12-year-old Ishmael

Beah’s village in Sierra Leone, they lined up

the boys (Beah 2007). One of the rebels

said,“We are going to initiate you by killing these peo-

ple.We will show you blood and make you strong.”

Before the rebels could do the killing, shots rang out

and the rebels took cover. In the confusion, Ishmael es-

caped into the jungle. When he returned, he found his

family dead and his village burned.

With no place to go and rebels attacking the villages,

killing, looting, and raping, Ishmael continued to hide in

the jungle.As he peered out at a village one day, he saw

a rebel carrying the head of a man, which he held by the

hair. With blood dripping from where the neck had

been, Ishmael said that the head looked as though it

were still feeling its hair being pulled.

Months later, government soldiers found Ishmael. The

“rescue” meant that he had to become a soldier—on

their side, of course.

Ishmael’s indoctrination was short but to the point.

Hatred is a strong motivator.

“You can revenge the death of your family, and make sure

that more children do not lose their parents,” the lieu-

tenant said. “The rebels cut people’s heads off. They cut

open pregnant women’s stomachs and take the babies out

and kill them. They force sons to have sex with their

mothers. Such people do not deserve to live. This is why

we must kill every single one of them.Think of it as de-

stroying a great evil. It is the highest service you can per-

form for your country.”

Along with thirty other boys, most of whom were

ages 13 to 16, with two just 7 and 11, Ishmael was

trained to shoot and clean an AK-47.

Banana trees served for bayonet practice.With

thoughts of disemboweling evil rebels, the boys would

slash at the leaves.

The things that Ishmael had seen, he did.

Killing was difficult at first, but after a while, as

Ishmael says,“killing became as easy as drinking water.”

The corporal thought that the boys were sloppy with

their bayonets.To improve their performance, he held a

contest. He chose five boys and placed them opposite

five prisoners with their hands tied. He told the boys to

slice the men’s throats on his command.The boy whose

prisoner died the quickest would win the contest.

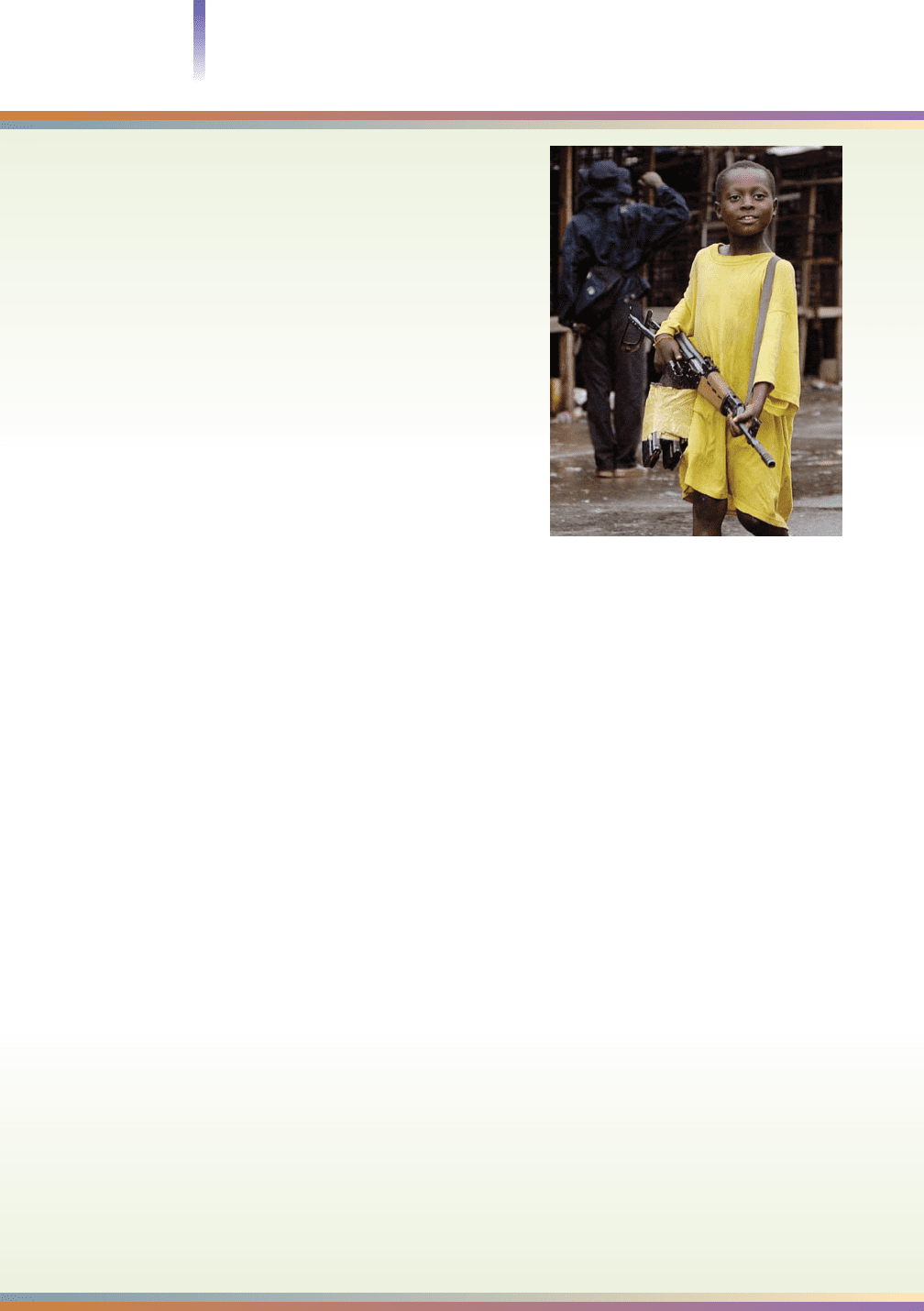

A boy soldier in Liberia.

Down-to-Earth Sociology

“I stared at my prisoner,” said Ishmael.“He was just an-

other rebel who was responsible for the death of my

family.The corporal gave the signal with a pistol shot, and

I grabbed the man’s head and sliced his throat in one fluid

motion. His eyes rolled up, and he looked me straight in

the eyes before they suddenly stopped in a frightful

glance. I dropped him on the ground and wiped my bayo-

net on him. I reported to the corporal who was holding a

timer. I was proclaimed the winner.The other boys

clapped at my achievement.”

“No longer was I running away from the war,” adds

Ishmael.“I was in it. I would scout for villages that had

food, drugs, ammunition, and the gasoline we needed. I

would report my findings to the corporal, and the entire

squad would attack the village.We would kill everyone.”

Ishmael was one of the lucky ones. Of the approxi-

mately 300,000 child soldiers worldwide, Ishmael is one

of the few who has been rescued and given counseling

at a UNICEF rehabilitation center. Ishmael has also had

the remarkable turn of fate of graduating from college

in the United States and becoming a permanent U.S.

resident.

For Your Consideration

1. Why are there child soldiers?

2. What can be done to prevent the recruitment of

child soldiers? Why don’t we just pass a law that re-

quires a minimum age to serve in the military?

3. How can child soldiers be helped? What agencies can

take what action?

Based on Beah 2007; quotations are summaries.

sold blueprints for atomic bombs to North Korea, Libya, and Iran (Perry et al. 2007). As

I write this, Iran and North Korea are furiously following those blueprints, trying to de-

velop their own nuclear weapons. In the hands of terrorists or a dictator who wants to set-

tle grudges—whether nationalistic or personal—these weapons can mean nuclear

blackmail or nuclear destruction, or both.

Making Alignments and Protecting Interests. The current alignments of the powerful

nations also sow the seeds of future conflicts. The seven richest, most powerful, and most

technologically advanced nations (Canada, France, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, Japan,

and the United States) formed a loose alliance which they called G7 (the Group of 7). The

goal was to coordinate their activities so they could perpetuate their global dominance, di-

vide up the world’s markets, and regulate global economic activity. Although Russia did

not qualify for membership on the basis of wealth, power, or technology, the other nations

feared Russia’s nuclear arsenal and invited Russia as an observer at its annual summits. Rus-

sia became a full member in 2002, and the organization is now called G8. Because China

has increased both its economic clout and its nuclear arsenal, it has been invited to be an

observer—a form of trial membership.

G8, soon to be G9, may be a force for peace—if these nations can agree on how to di-

vide up the world’s markets and force weaker nations to cooperate. Dissension became ap-

parent in 2003, however, when the United States attacked Iraq, with the support of only

Great Britain and Italy from this group. On several occasions, U.S. officials have vowed

that the United States will not allow Iran to become a nuclear power. If the United Na-

tions does not act and if a course similar to that which preceded the Iraq War is followed,

the United States, with the support of Great Britain, will bomb Iran’s nuclear facilities. An

alternative course of action is for the United States to quietly give the go-ahead to Israel

to do the bombing. One way or the other, the United States will protect its interests in

this oil-rich region of the world.

It does not take much imagination to foresee the implications of these current align-

ments: the propping up of cooperative puppet governments that support the interests of

G8, the threat of violence to those that do not cooperate, and the inevitable resistance—

including the use of terrorism—of various ethnic groups to the domination of these more

powerful countries. With these conditions in place, the perpetuation of war and terror-

ism is guaranteed.

A New World Order?

War and terrorism, accompanied as they so often are by torture and dehumanization, are

tools that some nations use to dominate other nations. So far, their use to dominate the

globe has failed. A New World Order, however, might be ushered in, not by war, but by

nations cooperating for economic reasons. Perhaps the key political event in our era is

the globalization of capitalism. Why the term political? Because politics and economics are

twins, with each setting the stage for the other.

Trends Toward Unity

As discussed in the previous chapter, the world’s nations are almost frantically embracing

capitalism. In this pursuit, they are forming cooperative, economic–political units. The

United States, Canada, and Mexico have formed a North American Free-Trade Associa-

tion (NAFTA). Eventually, all of North and South America may belong to such an organ-

ization. Ten Asian countries with a combined population of a half billion people have

formed a regional trading partnership called ASEAN (Association of South East Asian

Nations). Struggling for dominance is an even more encompassing group called the World

Trade Organization. These coalitions of trading partners, along with the Internet, are

making national borders increasingly insignificant.

The European Union (EU) may indicate a unified future. Transcending their national

boundaries, twenty-seven European countries (with a combined population of 450 million)

formed this economic and political unit. These nations have adopted a single, cross-national

A New World Order? 455

currency, the Euro, which has replaced their marks, francs, liras, lats, and pesetas. The EU

has also established a military staff in Brussels, Belgium (Mardell 2007).

Could this process continue until there is just one state or empire that envelops the

earth? It is possible. The United Nations is striving to become the legislative body of the

world, wanting its decisions to supersede those of any individual nation. The UN oper-

ates a World Court (formally titled the International Court of Justice). It also has a rudi-

mentary army and has sent “peacekeeping” troops to several nations.

Strains in the Global System

Although the globalization of capitalism and its encompassing trade organizations could lead

to a single world government, the strains in the developing global system are so great that they

threaten to rip the system apart. As noted in Chapter 9, it certainly isn’t easy to maintain

global stratification. Unresolved items constantly rear up, demanding realignments of the

current arrangements of power. Although these pressures are resolved on a short-term basis,

over time their accumulative weight leads to a gradual shift in global stratification.

If we take a broad historical view, we see that groups and cultures can dominate only so

long. They always come to an end, to be replaced by another group or culture. The process

of decline is usually slow and can last hundreds of years (Toynbee 1946), but in our

speeded-up existence, the future looms into the present at a furious rate. If the events of

the past century indicate the future, the decline of U.S. dominance—like that of Great

Britain—will come fairly quickly, although certainly not without resistance and blood-

shed. What the new political arrangements of world power will look like is anyone’s guess,

although there are indications that point to the ascendancy of China. Certainly the polit-

ical arrangements of the present will give way, creating a new world for future generations.

Building upon what we know about political power, we can be certain that whatever

the particular shape of future stratification, a political elite will be directing it, using its

resources to bolster its position, making alliances across international boundaries designed

to continue its dominance. Perhaps this process as it is currently unfolding will lead to a

one-world government. Only time will tell. In the meantime, a major blockage to global

unity is national patriotism and ethnic loyalties, a topic explored in the following

Thinking Critically section, which closes this chapter.

456 Chapter 15 POLITICS

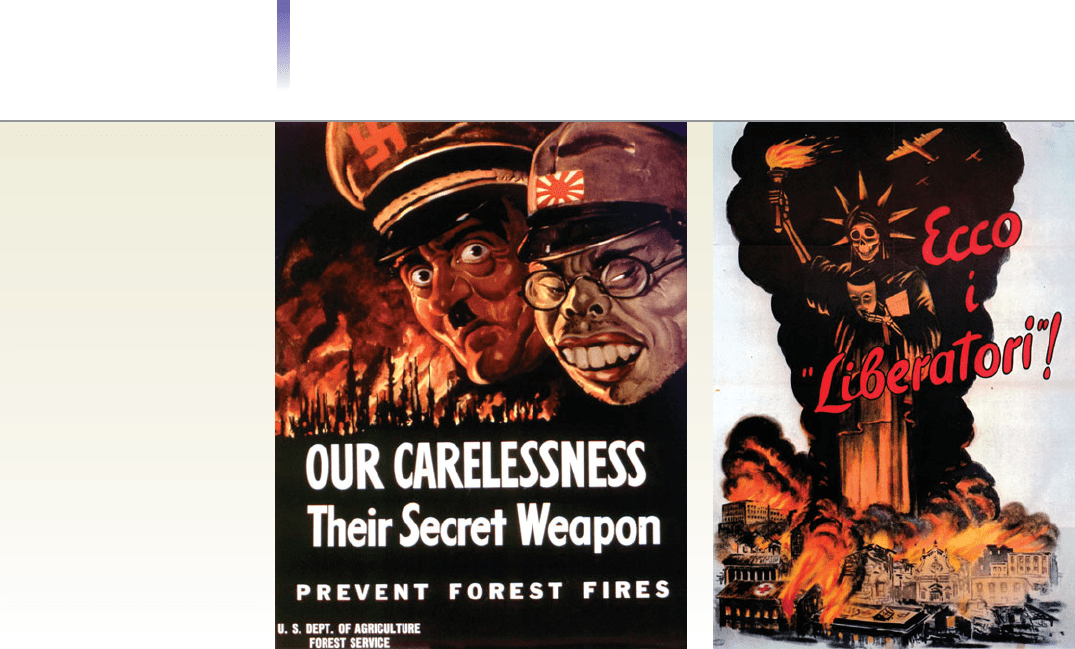

All governments—all the

time—use propaganda to

influence public opinion.

During times of war, the

propaganda becomes

more obvious. Note how

ugly Hitler and Tojo are

depicted on the World

War II poster from the

United States—and this is

just an ad to prevent

forest fires! In the other

poster, the Italian

government exposes

what Americans are

“really” like—in case any

Italians are going soft.

ThinkingCRITICALLY

Nationalism and Ethnic Loyalties: Roadblocks to the New

World Order

N

ation or state? What’s the difference? The world has about 5,000 nations, people

who share a language, culture, territory, and political organization. A state is another

name for “country.” Claiming a monopoly on violence over a territory, a state may

contain many nations. The Cataluns are one of the nations within the state called Spain.

The Chippewa and Sioux are two nations within the state called the United States. The

world’s 5,000 nations have existed for hundreds, some even for thousands, of years. In

contrast, most of the world’s states have been around only since World War II.

The nations that exist within states usually ended up there through conquest, leaving a bit-

ter harvest of resentment. Nation identity, much more personal and intense, usually trumps

state identity.The Palestinians who live within Israel’s borders, for example, do not identify

themselves as Israelis.The Oromos in Ethiopia, who have more members than do three-quar-

ters of the states in the United Nations, do not think of themselves as Ethiopians.The 22 mil-

lion Kurds don’t consider themselves first and foremost to be Iranians, Iraqis, Syrians, or Turks.

That nations are squeezed into states with which they don’t identify is the nub of the

problem. Nigeria has about 450 nations, India 350, Brazil 180, the former USSR 130, and

Ethiopia 90. Most states are controlled by a power elite that operates by a simple principle:

Winner takes all.To keep itself in power, this elite controls foreign investment and aid, levies

taxes—and buys weapons. A state obtains great wealth by confiscating the resources of the

nations under its control. The specifics are endless—Native American land in North and

South America, oil from the Kurds in Iraq, gold from the aborigines of Australia.When na-

tions resist, the result is armed conflict—and sometimes genocide.

G8’s attempt to establish a New World Order can be viewed as a drive to divide the world’s

resources on a global scale. The unexpected roadblock is the resurgence of nationalism—

identity with and loyalty to a nation. Nationalism strikes chords of emotions so deep that people

will kill—or give up their own lives. When nationalism erupts in a shooting war, the issues and

animosities are understood only faintly by those who are not a party to them; but nurtured in a

nation’s folklore and collective memory, they remain vividly alive to the participants.

The outcome of our present arrangements is seemingly contradictory: local shooting

wars alongside global coalitions. The local conflicts

come as nations struggle to assert their identity and

control, the coalitions as G8 tries to divide the

globe into regional trading blocs.With G8’s power,

David is not likely to defeat Goliath this time. Yet

there is a spoiler.Where David had five small stones

and needed only one, some nations have discovered

that terrorism is a powerful weapon. This, too, has

become part of the balance of global political

power.

For Your Consideration

Do you think we will have a one-world govern-

ment? Why or why not? If so, when? If a nation pos-

sesses self-identity and a common history and

culture, should it have the right to secede from a

state?

Sources: Clay 1990; Ohmae 1995; Marcus 1996; Hechter 2000; Ka-

plan 2003; Zakaria 2008.

A New World Order? 457

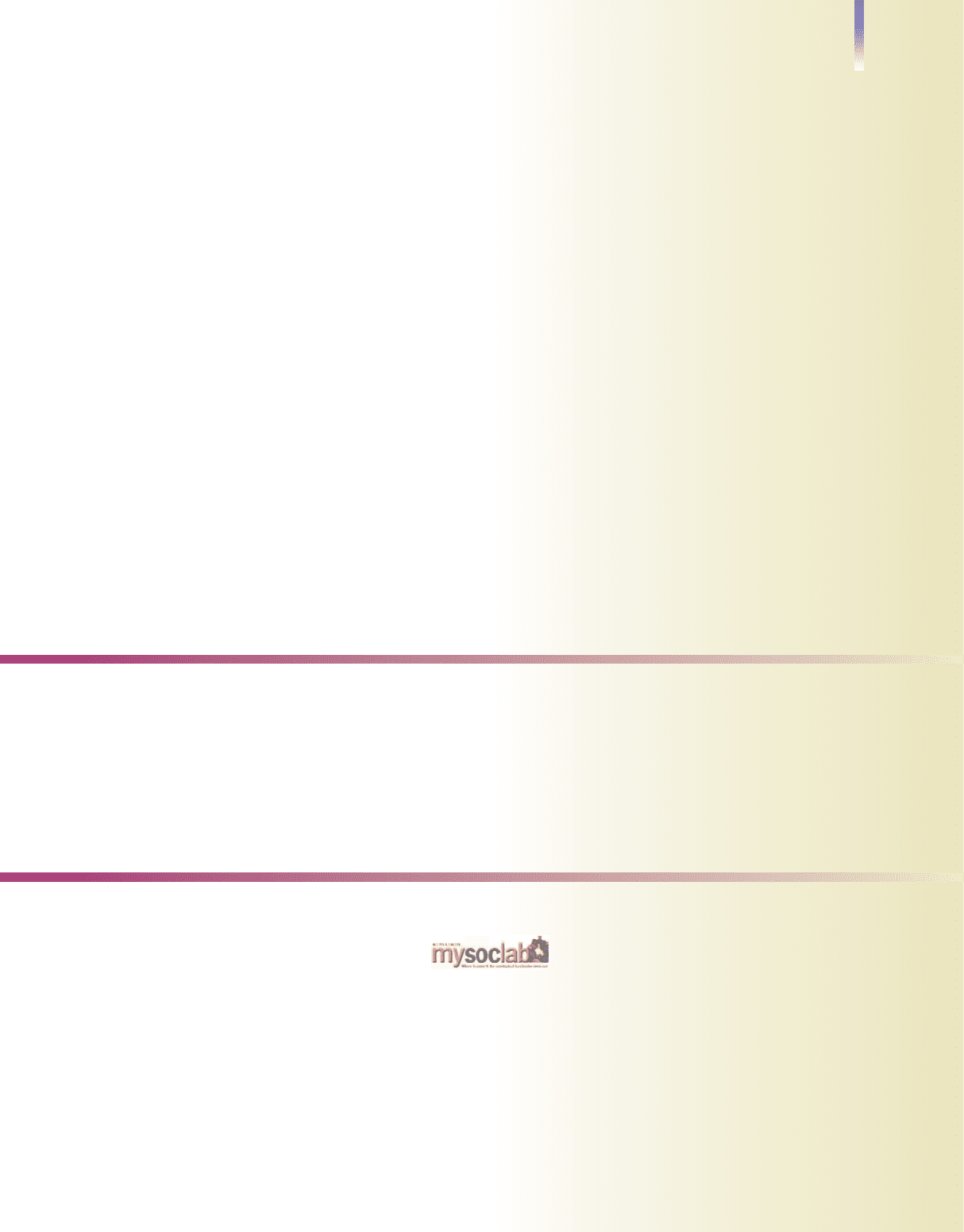

The depths of the roadblock to the New World Order were made apparent in

the 2008 conflict between Georgia and South Ossetia, especially when Russia

intervened militarily. Shown here is a Georgian woman crying over soldiers

buried in the rubble.

nationalism a strong identifi-

cation with a nation, accompa-

nied by the desire for that

nation to be dominant

458 Chapter 15 POLITICS

By the Numbers: Then and Now

SUMMARY and REVIEW

Micropolitics and Macropolitics

What is the difference between micropolitics

and macropolitics?

The essential nature of politics is power, and every group

is political. The term micropolitics refers to the exercise

of power in everyday life. Macropolitics refers to large-

scale power, such as governing a country. P. 432.

Power, Authority, and Violence

How are authority and coercion related to power?

Authority is power that people view as legitimately ex-

ercised over them, while coercion is power they consider

unjust. The state is a political entity that claims a mo-

nopoly on violence over some territory. If enough peo-

ple consider a state’s power illegitimate, revolution is

possible. Pp. 432–433.

What kinds of authority are there?

Max Weber identified three types of authority. In traditional

authority, power is derived from custom—patterns set

down in the past serve as rules for the present. In

rational–legal authority (also called bureaucratic authority),

power is based on law and written procedures. In

charismatic authority, power is derived from loyalty to an

individual to whom people are attracted. Charismatic au-

thority, which undermines traditional and rational–legal au-

thority, has built-in problems in transferring authority to a

new leader. Pp. 433–435.

Types of Government

How are the types of government related to power?

In a monarchy, power is based on hereditary rule; in a

democracy, power is given to the ruler by citizens; in a

dictatorship, power is seized by an individual; and in an

oligarchy, power is seized by a small group. Pp. 436–439.

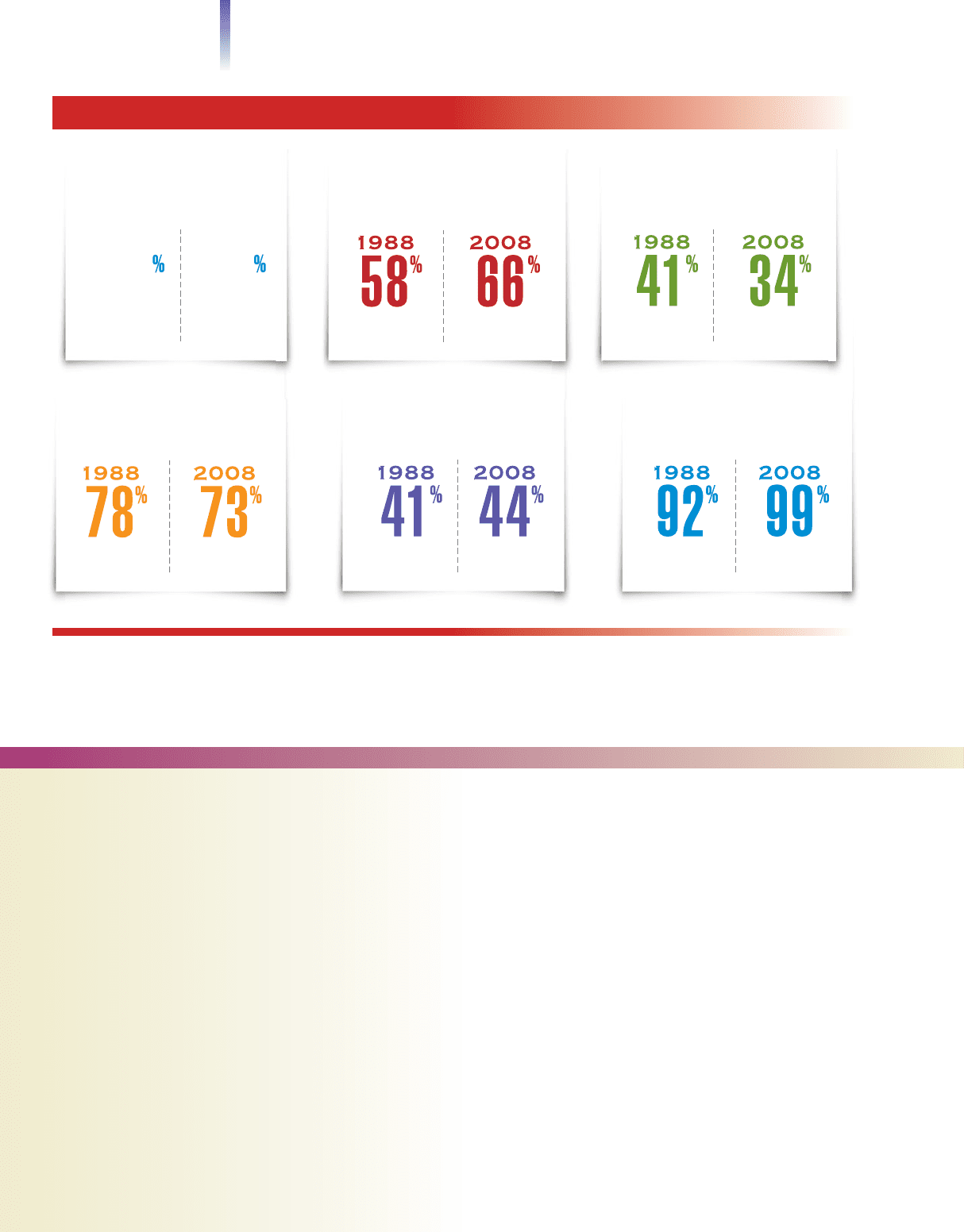

1988 2008

African Americans

who voted for a

Democratic president

%%

2008

College graduates who voted

in the presidential election

%

1988

%

Whites who voted for a

Democratic president

1988 2008

%%

Women who voted in the

presidential election

1988 2008

%%

African Americans

High school drop-outs

who voted in the

presidential election

1988 2008

%%

Men who voted in the

presidential election

198 8

56

2008

62

%%

Summary and Review 459

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT Chapter 15

1. What are the three sources of authority, and how do they

differ from one another?

2. What does biological terrorism have to do with politics?

What does the globalization of capitalism have to do with

politics?

3. Apply the findings on “Why Nations Go to War” (page

449) to a recent war that the United States has been a

part of.

The U.S. Political System

What are the main characteristics of the U.S.

political system?

The United States has a “winner take all” system, in which

a simple majority determines the outcome of elections.

Most European democracies, in contrast, have

proportional representation; legislative seats are allotted

according to the percentage of votes each political party

receives. Pp. 439–441.

Voter turnout is higher among people who are more

socially integrated—those who sense a greater stake in the

outcome of elections, such as the more educated and well-

to-do. Lobbyists and special-interest groups, such as

political action committees (PACs), play a significant

role in U.S. politics. Pp. 441–446.

Who Rules the United States?

Is the United States controlled by a ruling class?

In a view known as pluralism, functionalists say that no

one group holds power, that the country’s many compet-

ing interest groups balance one another. Conflict theo-

rists, who focus on the top level of power, say that the

United States is governed by a power elite, a ruling class

made up of the top corporate, political, and military lead-

ers. At this point, the matter is not settled. Pp. 446–448.

War and Terrorism: Implementing

Political Objectives

How are war and terrorism related to politics—and

what are their costs?

War and terrorism are both means of attempting to accom-

plish political objectives. Timasheff identified three essential

conditions of war and seven fuels that ignite antagonistic sit-

uations into war. His analysis can be applied to terrorism.

Because of technological advances in killing, the costs of war

in terms of money spent and human lives lost have esca-

lated. Another cost is dehumanization, whereby people no

longer see others as worthy of human treatment. This paves

the way for torture and killing. Pp. 448–455.

A New World Order?

Is humanity headed toward a world

political system?

The globalization of capitalism and the trend toward re-

gional economic and political unions may indicate that a

world political system is developing. Oppositional forces

are global economic crises, ethnic loyalties, and

nationalism. Pp. 455–458.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

What can you find in MySocLab? www.mysoclab.com

• Complete Ebook

• Practice Tests and Video and Audio activities

• Mapping and Data Analysis exercises

• Sociology in the News

• Classic Readings in Sociology

• Research and Writing advice

Where Can I Read More on This Topic?

Suggested readings for this chapter are listed at the back of this book.

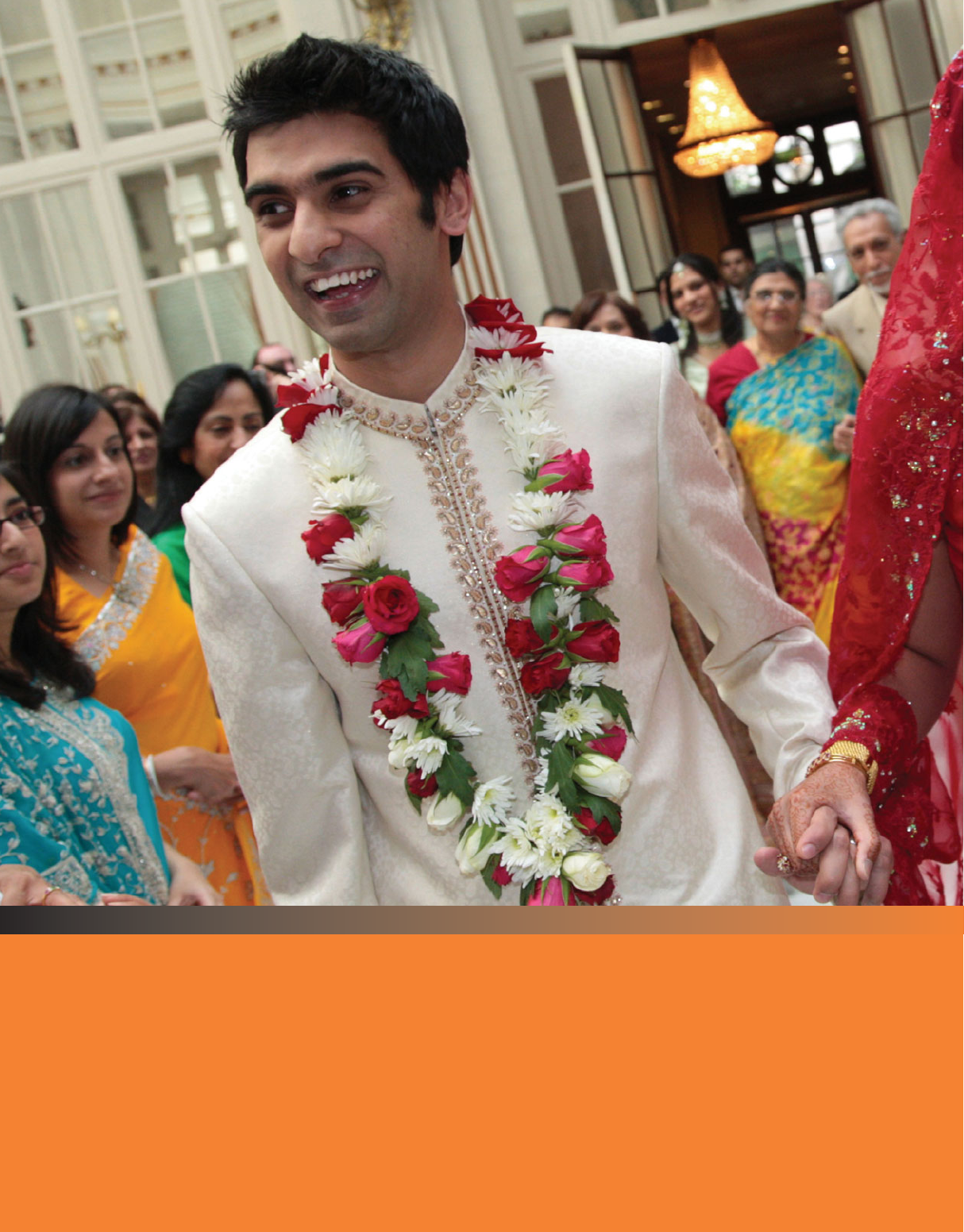

Marriage and Family

16

Chapter