Henslin James M. Sociology: A Down to Earth Approach

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

one that can be upset at any time. Following this

principle, could conflict between the elderly and

the young be in our future? Let’s consider this

possibility.

If you listen closely, you can hear ripples of

grumbling—complaints that the elderly are

getting more than their fair share of society’s

resources. The huge costs of Social Security

and Medicare are a special concern. One of

every three tax dollars (32 percent) is spent on

these two programs (Statistical Abstract

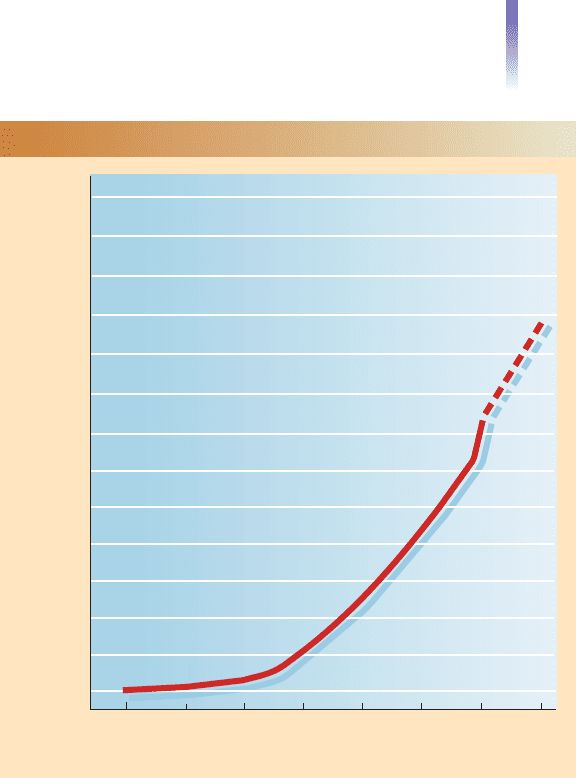

2011:Table 471). As Figure 13.8 shows, Social

Security payments were $781 million in 1950;

now they run 870 times higher. Now look at

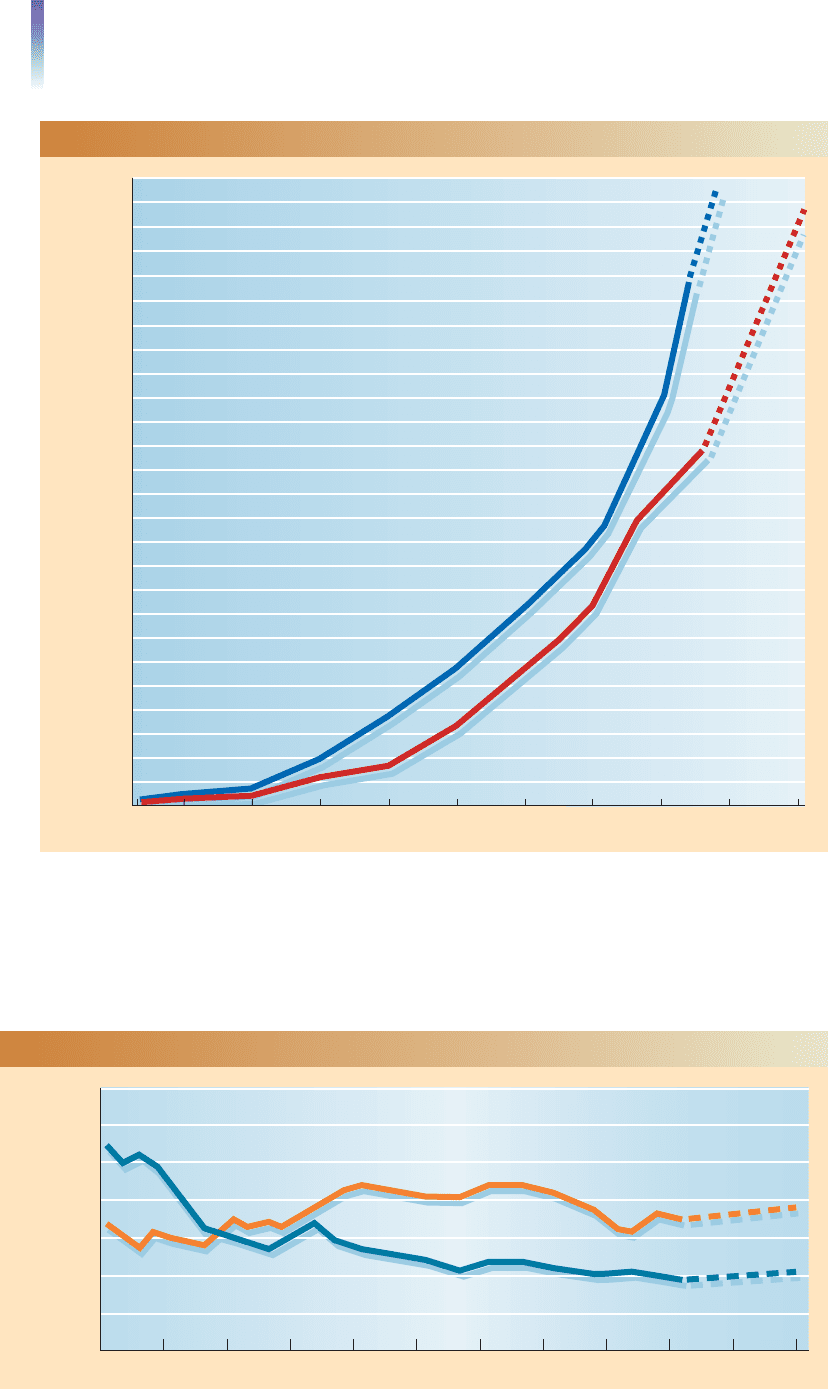

Figure 13.9 on the next page, which shows the

nation’s medical bill to care for the elderly. Like

gasoline poured on a bonfire, these soaring

costs may well fuel a coming intergenerational

showdown.

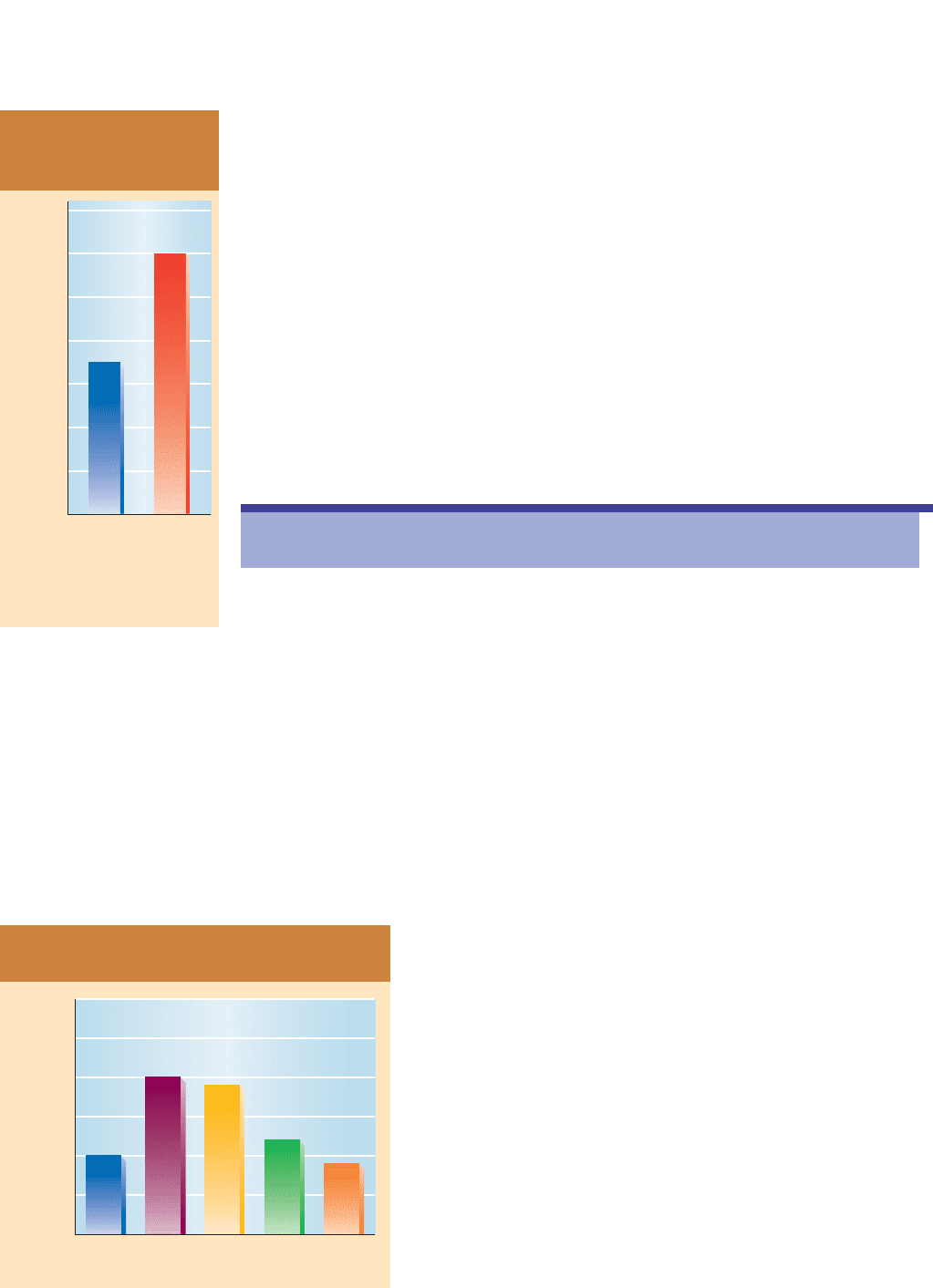

Figure 13.10 on the next page shows another

area of concern that can fuel an intergenerational

conflict. You can see how greatly the condition

of the elderly improved as the government trans-

ferred resources to them. But look also at the

matching path of children’s poverty. Even with its

recent decline, children’s poverty is just as high

now as it was in 1967. Certainly the decline in

the elderly’s rate of poverty did not come at the

expense of the nation’s children. Congress could

have decided to finance the welfare of children

just as it has that of the elderly. It has chosen not

to. One fundamental reason, following conflict theorists, is that the children have not

launched as broad an assault on Congress. Simply put, the lobbyists for the elderly have

put more grease in the political reelection machine.

Figure 13.10 could be another indicator of a coming intergenerational storm. If we

take a 10 percent poverty rate as a goal for the nation’s children—just to match what

the government has accomplished for the elderly—where would the money come

from? If the issue gets pitched as a case of money going to one group at the expense

of another group, it can divide the generations. To get people to think that they must

choose between pathetic children and suffering old folks can splinter them into oppos-

ing groups, breaking their power to work together to improve society. The Down-to-

Earth Sociology box on page 383 examines stirrings of resentment that could become

widespread.

Fighting Back

Some organizations work to protect the gains of the elderly. Let’s consider two.

The Gray Panthers. The Gray Panthers, who claim 20,000 members, are aware how eas-

ily the public can be split along age lines (Gray Panthers n.d.). This organization encour-

ages people of all ages to work for the welfare of both the old and the young. On the micro

level, their goal is to help people develop positive self-concepts (Kuhn 1990), and on the

macro level, to build a base so broad that it can challenge institutions that oppress the poor,

whatever their age, and fight attempts to pit people against one another along age lines. One

indication of their effectiveness is that Gray Panthers frequently testify before congressional

committees concerning pending legislation.

The Conflict Perspective 381

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

Billions of Dollars

900

1,000

1,100

1,200

$1,300

1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010

20201950

Year

FIGURE 13.8 Social Security Payments to Beneficiaries

Source: By the author. Based on Statistical Abstract of the United States 1997:

Table 518; 2011:Table 471. Broken line indicates the author’s projections.

382 Chapter 13 THE ELDERLY

Billions of Dollars

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

200

220

240

260

280

300

420

320

340

360

380

400

440

460

480

500

$520

1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2010 20152005

Medicare

Medicaid

Year

1970 19751967

FIGURE 13.9 Health Care Costs for the Elderly and Disabled

Source: By the author. Based on Statistical Abstract, of the United States various years, and

2011:Tables 146, 147. Broken lines indicate the author’s projections.

Percentage

1967

0

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

1971 1975 1979 1983 1987 1991 1995 2000

35

%

2005 20152010

Elderly (65 and over)

Youth (under 18)

Year

FIGURE 13.10 Age and Trends in Poverty

Source: By the author. Statistical Abstract of the United States, various years, and 2011:Table 712. Broken lines

indicate the author’s projections.

Note: Medicare is intended for the elderly and disabled, Medicaid for the poor. About 20 percent of

Medicaid payments (over $60 billion) go to the elderly (Statistical Abstract 2011:Table 147).

The Conflict Perspective 383

Stirrings of Resentment About

the U.S. Elderly

I

n the past, most U.S. elderly were poor. Social Secu-

rity has been so successful that, as we saw in Figure

10.6 on page 282, the poverty rate of today’s elderly is

less than the national average. Many of the elderly who

draw Social Security don’t need it. Despite our eco-

nomic crisis, many elderly still travel about the country

in motor homes and spend huge amounts on recre-

ation. The golf courses, although thinned, continue to be

popular with retired Americans. The cruise ships still

wend their way to exotic destinations. Is the relative

prosperity of the elderly in the midst of economic hard-

ships for many creating resentments?

There are indications that it is. Many younger people

have begun to question “senior citizen discounts.” “Why

should old folks pay less for a meal or for a hotel room

than I do?” they wonder. Some of the younger know

their parents’ situation: They have paid off their home,

own investment property, collect a private pension from

their former employer, and collect social security. Why

should they—or anyone else—be automatically entitled

to a “senior citizen discount,” they wonder. . . .

In one of the more bizarre reactions to the growing

political power of the elderly, one of our senators, who

just happened to head the Senate Committee on Social

Security, called the retired “greedy geezers” who de-

mand government handouts while they “tee off near

their second homes in Florida” (Duff 1995). Of course,

senators say most anything if they feel it is popular. This

particular senator later retired, quickly grabbed his gen-

erous Senate pension, and became a “greedy geezer”

himself, teeing off from his own second home.

Another indication of changing sentiment is that

some have begun to argue that we should ration med-

ical care for the elderly (Thau 2001). Open-heart sur-

gery is a favorite example. For people in their 80s, this

costly operation prolongs life by only two or three

years. Since our resources are limited, they say it makes

more sense to pay for a kidney transplant for a child,

whose life might be prolonged by fifty years.

For Your Consideration

These questions, brought up only tentatively in the

United States, are being asked more openly in countries

that have larger proportions of elderly. In Austria, for

example, even resentments about old age pensions have

become front page news (Aichinger 2007). How do you

see future relationships between the elderly and the

younger?

Finally, if seniors have it so good, why do you see so

many of them working at Wal-Mart?

Attitudes toward the elderly have undergone major shifts during the

short history of the United States. As the economic circumstances of

the elderly improve, attitudes are changing once again.

Down-to-Earth Sociology

The American Association of Retired Persons. The AARP also champions legislation

to benefit the elderly. With 39 million members, this organization has political clout. It

monitors federal and state legislation and mobilizes its members to act on issues affecting

their welfare. A statement of displeasure about some proposed law from the AARP can

trigger tens of thousands of telephone calls, telegrams, letters, and e-mails from irate eld-

erly citizens. To protect their chances of reelection, politicians try not to cross swords with

the AARP. As you can expect, critics claim that this organization is too powerful, that it

muscles its way to claim more than its share of the nation’s resources.

In Sum: All of these points—from Social Security and Medicare to organizations that

lobby for the elderly—support our position, say conflict theorists. Age groups are one of

society’s many groups that are competing for scarce resources. At some point, conflict is

the inevitable result.

Recurring Problems

“When I get old, will I be able to take care of myself ? Will I become frail and unable to

get around? Will I end up in some nursing home, in the hands of strangers who don’t care

about me?” These are common concerns of people as they age. Let’s first examine gender

and the elderly and then the problems of nursing homes, abuse, and poverty.

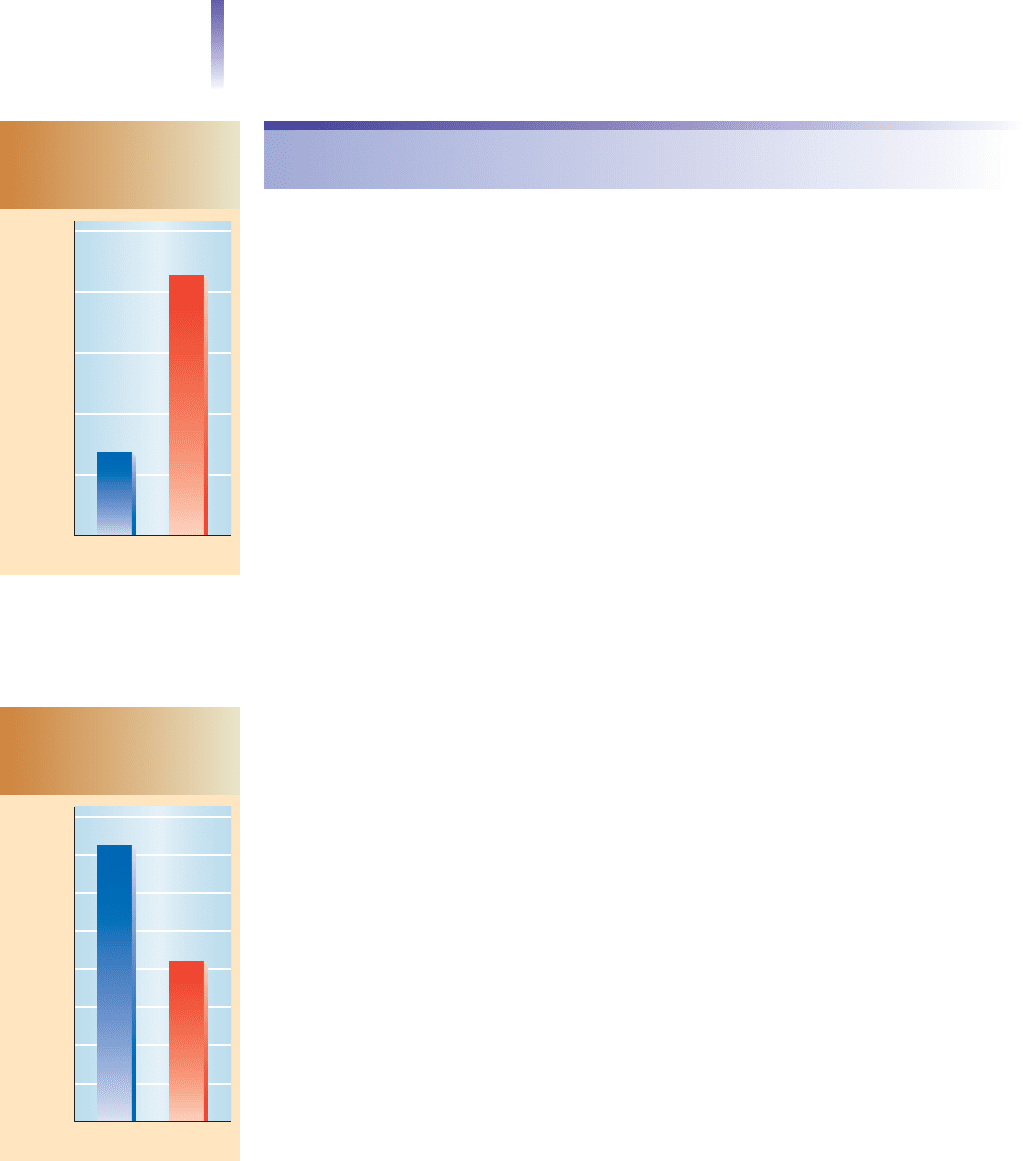

Gender and the Elderly

In Chapter 11, we examined how gender influences our lives. The impact of gender

doesn’t stop when we get old. Because most women live longer than most men, women

are more likely to experience the loneliness and isolation that widowhood often brings.

This is one implication of Figure 13.11, which shows how much more likely women are

to be widowed. This difference in mortality also leads to different living arrangements in

old age. Figure 13.12 shows how much more likely elderly men are to be living with their

wives than elderly women are to be living with their husbands. Another consequence is

that most patients in nursing homes are women.

Before we review nursing homes, I think you will enjoy reading the

Down-to-Earth Sociology box on the next page. It will give you a glimpse of some of the

variety that exists among the elderly, as well as how people carry gender roles into old age.

Nursing Homes

In one nursing home, the nurses wrote in the patient’s chart that she had a foot lesion. She

actually had gangrene and maggots in her wounds (Rhone 2001). In another nursing home—

supposedly a premier retirement home in Southern California—a woman suffered a stroke

in her room. Her “caretakers” didn’t discover her condition for 15 hours. She didn’t survive.

(Morin 2001)

Most elderly are cared for by their families, but at any one time a million and a half

Americans age 65 and over are in nursing homes. This comes to about 4 percent of the

nation’s elderly (Statistical Abstract 2011:Tables 9, 190). Some patients return home after

only a few weeks or a few months. Others die after a short stay. Overall, about one half

of elderly women and one-third of elderly men spend at least some time in nursing homes.

Nursing home residents are not typical of the elderly. Three of four are age 75 or

older. Almost all (80 percent) are widowed or divorced, or have never married, leav-

ing them without family to care for them. Most of these elderly are in such poor health

that they need help to bathe, dress, and eat (Centers for Disease Control and Preven-

tion 2008d).

Understaffing, Dehumanization, and Death. It is difficult to say good things about

nursing homes. The literature on nursing homes, both popular and scientific, is filled

with horror stories of neglected and abused patients. Ninety percent of nursing homes fail

federal inspections for health and safety (Pear 2008). With events like those in the quo-

tation that opens this section, Congress ordered a national study of nursing homes. The

researchers found that in nursing homes that are understaffed, patients are more likely to

have bedsores and to be malnourished, underweight, and dehydrated. Ninety percent of

nursing homes are understaffed (Pear 2002).

It is easy to see why nursing homes are understaffed. Who—if he or she has a choice—

works for poverty-level wages in a place that smells of urine, where you have to clean up

feces, and where you are surrounded by dying people? Forty to one hundred percent of

nursing home staff quit each year (DeFrancis 2002).

But all the criticisms of nursing homes pale in comparison with this finding: Compared

with the elderly who have similar health conditions but remain home, those who go to

nursing homes tend to get sicker and to die sooner (Wolinsky et al. 1997). This is a

remarkable finding. Could it be, then, that a function of nursing homes is to dispose of

384 Chapter 13 THE ELDERLY

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0

Percentage

Men

13%

Women

42%

FIGURE 13.11

The Elderly Who

Are Widowed

Source: By the author. Based on

Statistical Abstract of the United

States 2011:Table 34.

80%

40%

50%

60%

70%

30%

20%

10%

0

Percentage

Men

73%

Women

42%

FIGURE 13.12

The Elderly Who Live

with a Spouse

Source: By the author. Based on

Statistical Abstract of the United

States 2011:Table 34.

Recurring Problems 385

Feisty to the End: Gender Roles

Among the Elderly

T

his image of my father makes me smile—not be-

cause he was arrested as an old man, but, rather,

because of the events that led to his arrest. My

dad had always been a colorful character, ready with

endless, ribald jokes and a hearty laugh. He carried

these characteristics into his old age.

In his late 70s, my dad was living in a small apartment

in a complex for the elderly in Minnesota. The adjacent

building was a nursing home, the next destination for

the residents of these apartments. None of them liked

to think about this “home,” because no one survived

it—yet they all knew that this would be their destina-

tion. Under the watchful eye of these elderly neighbors,

care in the nursing home was fairly good. Until they

were transferred to this unwelcome last stopping-place,

life for them went on “as usual” in the complex for the

elderly.

According to the police report and my dad’s account,

here is what happened:

Dad was sitting in the downstairs lounge with other resi-

dents, waiting for the mail to arrive, a daily ritual that the

residents looked forward to. For some reason known

only to him, my dad hooked his cane under the dress of

an elderly woman, lifted up her skirt, and laughed. Under-

standably, this upset her, as well as her husband, who was

standing next to her. Angry, the man moved toward my

father, threatening him.

I say “moved,” rather than “lunged,” because this man

was using a walker. My dad started to run away from this

threat. Actually,“run” isn’t quite the right word.“Hobbled”

would be a better term.

My dad fled as fast as he could using his cane, while the

other man pursued him as fast as he could using his

walker. Wheezing and puffing, the two went from the

lounge into the long adjoining hall, pausing now and then

to catch their breath. Tiring the most, the other man gave

up the pursuit. He then called the police.

When the police officer arrived, he said,“Uncle Marv,

I’m sorry, but I’m going to have to arrest you.” (This event

occurred in a small town, and the officer assigned this case

turned out to be Dad’s nephew.)

Dad went before a judge, who could hardly keep a

straight face. He gave Dad a small fine and warned him to

behave himself. The apartment manager also gave Dad a

warning: One more incident, and he would have to move

out of the complex.

Dad’s wife wasn’t too happy about the situation,

either.

This event was brought to mind by a newspaper ac-

count of a fight that broke out at the food bar of a re-

tirement home (“Melee Breaks” . . . 2004). It seems

that one elderly man criticized the way another man

was picking through the salad.When a fight broke out

between the two, several elderly people were hurt as

they tried either to intervene or to flee.

For Your Consideration

People carry their personalities, values, and other traits

into old age. Among these characteristics are gender

roles. What examples of gender roles do you see in

the events related here? Are you familiar with how

old people continue to show their femininity or

masculinity?

Down-to-Earth Sociology

During their elderly years, men and women continue to

exhibit aspects of the gender roles that they learned and

played in their younger years.

the frail and unwanted elderly? If so, could we consider nursing homes the Western equiv-

alent of the Tiwi’s practice of “covering up,” which we reviewed in this chapter’s opening

vignette?

Perhaps this judgment is too harsh. But there are alternatives, and yet we continue

with the depressing nursing homes that all of us want to avoid. We explore more pleas-

ant alternatives in the Down-to-Earth Sociology box on the next page.

386 Chapter 13 THE ELDERLY

Do You Want to Live

in a Nursing Home?

You have just turned 75—or 85—or 95,

and the dreaded moment has come.You

know you’ve been a “little” forgetful

lately, but it couldn’t be this bad.That’s a

county sheriff’s vehicle that just pulled

up to your house.You know they’re

going to take you to a nursing home.

“Over my dead body!” you shout

to no one, as you begin to frantically

barricade the door. “They’re not com-

ing in here. I’d rather die!”

While one deputy diverts your at-

tention at the front door, another

crawls in a back window. He grabs you

from behind, pins your frail arms be-

hind you while he opens the door with

the other hand. The two deputies drag

you screaming and kicking to their car.

* * *

But wait a minute. It didn’t happen like that at all. Instead,

you were packed up and waiting—with a big grin on your

face.“Finally, I get to go to the home for the elderly,” you say

to yourself, as you open the door to welcome the two offi-

cials who are going to take you to live with your new friends.

“That first version is a little extreme—barricade and all—

but so is the second one,” you might say, adding,“Never in

my life would I want to live in a nursing home!” That reac-

tion is understandable.The isolation, the coldness, the har-

ried staff, the neglect, people calling you “dearie” and talking

to you like you’re a child, the antipsychotic drugs given to

people who have no psychosis, to “calm” anyone who gets

out of line—make nursing homes depressing, feared places.

Do nursing homes have to be like this? Can’t we do

better—a lot better? Could we even turn them into

places so warm and inviting that the second version of

our little story could be true—that you would look for-

ward to living there when you are old?

Some visionaries say that we can transform nursing

homes into warm, inviting places. They started with a

clean piece of paper and asked how we could redesign

nursing homes so they enhance or maintain people’s qual-

ity of life. The model they came up with doesn’t look or

even feel like a nursing home. (And it certainly doesn’t

smell like one.) In Green Houses, as they are called,

elderly people live in a homelike setting (Lagnado 2008).

Instead of a sterile hallway lined with rooms, 10 to 12

residents live in a carpeted ranch-style house. They re-

ceive medical care suited to their personal needs, share

meals at a communal dining table, and, if they want to,

they can cook together in an open kitchen. As shown in

the photo above, they can even play virtual sports on

plasma televisions. This home-like setting fosters a sense

of community among residents and staff.

Taking a different approach, the elderly themselves are

developing a second model, neighborhood support

groups. The goal is to avoid nursing homes altogether,

no matter how good they might be. In some areas, such

as Beacon Hill in Boston, the neighborhood support

group replaces the caring, nearby adult children that

many lack (Gross 2007). In return for annual dues, just a

phone call away are screened carpenters, house clean-

ers—even someone to drop by and visit. In one version

of these neighborhood support groups, members ex-

change services. Those who are still able to fix faucets,

for example, do so. They bank that time, exchanging it for

something they need, such as transportation to the doc-

tor. This concept, simple and promising, lets the elderly

live in their own homes, remaining in the neighborhood

they know so well and in which they feel comfortable.

For Your Consideration

Of the two models presented here, Green Houses and

neighborhood support groups, which would you prefer

if you were elderly? Why? What are the limitations of

each model?

These members of a Wii bowling team illustrate the developing concept of homes for the

elderly: active old people enjoying themselves in home-like settings.

Down-to-Earth Sociology

Elder Abuse

You’ve probably heard stories of elder abuse, about residents of nursing homes being

pushed, grabbed, shoved, or shouted at. Some of the elderly in nursing homes are also

abused sexually (Ramsey-Klawsnik et al. 2008). Others are abused at home, by family

members who exploit them financially or abuse them physically.

While abuse of the elderly certainly occurs, it is not typical. Less than 4 percent of the

U.S. elderly experience financial abuse, and less than 1 percent are abused physically (Lau-

mann et al. 2008). Few of the abusers are “mean” people. One of the most common rea-

sons for abuse is that a family member has run out of patience. The husband of a woman

who was suffering from Alzheimer’s disease said this to the social scientists who inter-

viewed him

Frustration reaches a point where patience gives out. I’ve never struck her, but sometimes I

wonder if I can control myself. . . . This is...the part of her care that causes me the frus-

tration and the loss of patience. What I tell her, she doesn’t register. Like when I tell her,

“You’re my wife.” “You’re crazy,” she says. (Pillemer and Suitor 1992)

This quote is not intended to excuse any abuse, but, rather, to gain insight into why

anyone would abuse a family member. From what this husband said, we can glean some

insight into the stress that comes with caring for a person who is dependent, demanding,

and uncomprehending. Since most people who care for the elderly undergo stress but are

not violent toward those they care for, however, we do not have the answer to why some

caregivers become violent. For this, we must await future research.

More important than understanding the causes of abuse, however, is preventing the

elderly from being abused in the first place. There is little that can be done about abuse

at home by relatives—except to enforce current laws when abuse comes to the atten-

tion of authorities. For home-care and nursing home workers, in contrast, we can re-

quire background checks to screen out people who have been convicted of robbery,

rape, and other violence. This is similar to requiring background checks of preschool

workers in order to screen out people who have been convicted of molesting children.

Such laws are only a first step to solving this problem. They will not prevent abuse,

only avoid the obvious.

Recurring Problems 387

In old age, as in all other stages of the life course, people find life more pleasant if they have friends and

enough money to meet their needs. How do you think that an elderly man who lives by himself in a

rundown camper finds life? How about elderly married people who get together for lunch with friends

of many years? While neither welcomes old age, you can see what a difference social factors make in

how people experience this time of life.

The Elderly Poor

Many elderly live in nagging fear of poverty. Not knowing how long they will live nor how

much inflation they will face, they fear that they will outlive their savings. How realistic

is this fear? Statistics don’t apply to any individual case, but they help us to understand

how earlier social patterns carry over to the elderly as a group.

Gender and Poverty. As reviewed in Chapter 11, during their working years most

women earn less than men. Figure 13.13 shows how this pattern follows women and men

into their old age. As you can see, elderly women are about 70 percent more likely than

elderly men to be poor.

Race–Ethnicity and Poverty. As we reviewed earlier, Social Security has lifted most

elderly Americans out of poverty, and today’s elderly are less likely than the average

American to be poor. There is poverty among the elderly, of course, and it follows the

racial–ethnic patterns of the general society. From Figure 13.14, you can see how much

less likely elderly whites and Asian Americans are to be poor than are African Ameri-

cans and Latinos.

The Sociology of Death and Dying

Have you ever noticed how people use language to try to distance themselves from

death? We have constructed linguistic masks, ways to refer to death without using the

word itself. Instead of dead, we might say “gone,” “passed on,” “no longer with us,” or

“at peace now.” We don’t have space to explore this fascinating characteristic of social

life, but we can take a brief look at why sociologists emphasize that dying is more than

a biological event.

Industrialization and the New Technology

Before industrialization, death was no stranger. The family took care of the sick at home,

and the sick died at home. Because life was short, most children saw a sibling or parent

die (Blauner 1966). As noted in Chapter 1 (page 26), the family even prepared corpses

for burial. Industrialization changed this. As secondary groups came to dominate society,

the process of dying was placed in the hands of professionals in hospitals. Dying now

takes place behind closed doors—isolated, remote, and managed by strangers. As a re-

sult, for most of us death has become something strange and alien.

Not only did new technologies remove the dying from our pres-

ence, but they also created technological life—a form of existence

that lies between life and death, but is neither (Cerulo and Ruane

1996). The “brain dead” in our hospitals have no self. Their “per-

son” is gone—dead—yet our technology keeps the body alive. This

muddles the boundary between life and death, which used to seem

so certain.

For most of us, however, that boundary will remain firm, and we

will face a definite death. Some of us will even learn in advance

that we will die shortly. If so, how are we likely to cope with this

knowledge? Let’s look at what researchers have found.

Death as a Process

Let me share an intimate event from my own life.

When my mother was informed that she had inoperable lung cancer,

she went into a vivid stage of denial. If she later went through anger or

negotiation, she kept it to herself. After a short depression, she experi-

388 Chapter 13 THE ELDERLY

Percentage

0

30%

25%

20%

15%

10%

5%

10%

9%

12%

19%

20%

African

Americans

Latinos WhitesAsian

Americans

Overall

FIGURE 13.14 Race–Ethnicity

and Poverty in Old Age

Source: By the author. Based on Statistical Abstract of the

United States 2011:Table 712.

14%

10%

8%

6%

4%

0

12%

2%

Percentage

Men

7.0%

Women

12.0%

The percentage of

Americans aged 65

and older who

are poor

FIGURE 13.13

Gender and Poverty

in Old Age

Source: By the author. Based on

Statistical Abstract of the United

States 2011:Table 34.

enced a longer period of questioning why this was happening to her. After coming to grips

with the fact that she was going to die soon, she began to make her “final arrangements.”

The extent of those preparations soon became apparent.

After her funeral, my two brothers and I went to her apartment, as she had instructed

us. There, to our surprise, attached to each item in every room—from the bed and the tel-

evision to the boxes of dishes and knickknacks—was a piece of masking tape with one of

our names on it. At first we found this strange. We knew she was an orderly person, but

to this extent? As we sorted through her things, reflecting on why she had given certain

items to whom, we began to appreciate the “closure” she had given to this aspect of her

material life.

Psychologist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross (1969/2008) studied how people cope during the

living–dying interval, that period between discovering they are going to die soon and death

itself. After interviewing people who had been informed that they had an incurable dis-

ease, she concluded that people who come face to face with their own death go through

five stages:

1. Denial. At first, people cannot believe that they are going to die. (“The doctor must

have made a mistake. Those test results can’t be right.”) They avoid the topic of

death and situations that remind them of it.

2. Anger. After a while, they acknowledge that they are going to die, but they view

their death as unjust. (“I didn’t do anything to deserve this. So-and-so is much worse

than I am, and she’s in good health. It isn’t right that I should die.”)

3. Negotiation. Next, the individual tries to get around death by making a bargain with

God, with fate, or even with the disease itself. (“I need one more Thanksgiving with

my family. I never appreciated them as much as I should have. Let me just hold out

until then.”)

4. Depression. During this stage, people become resigned to their death, but they

grieve because their life is about to end, and they have no power to change the

course of events.

5. Acceptance. In this final stage, people come to terms with their impending death.

They put their affairs in order—make wills, pay bills, instruct their children to take

care of the surviving parent. They also express regret at not having done certain

things when they had the chance. Devout Christians are likely to talk about the

hope of salvation and their desire to be in heaven with Jesus.

Dying is more individualized than this model indicates. Not everyone, for example,

tries to make bargains. What is important sociologically is that death is a process, not just

an event. People who expect to die soon face a reality quite different from the one expe-

rienced by those of us who expect to be alive years from now. Their impending death

powerfully affects their thinking and behavior.

Hospices

What a change. In earlier generations, life was short, and people took death at an early

age for granted. Today, we take it for granted that most people will see old age. Due

to advances in medical technology and better public health practices, most deaths in

the United States (about 75 percent) occur after age 65. People want to die with dig-

nity, in the comforting presence of friends and relatives, but hospitals, to put the mat-

ter bluntly, are awkward places in which to die. There people experience what

sociologists call institutional death—they die surrounded by strangers in formal garb,

in sterile rooms filled with machines, in an organization that puts its routines ahead

of patients’ needs.

Hospices emerged as a way to reduce the emotional and physical burden of dying—

and to lower the costs of death. Hospice care is built around the idea that the people who

are dying and their families should control the process of dying. The term hospice orig-

inally referred to a place, but now it generally refers to home care. Services are brought into

The Sociology of Death and Dying 389

hospice a place (or services

brought to someone’s home)

for the purpose of giving com-

fort and dignity to a dying

person

a dying person’s home—from counseling and managing pain to such basic help as pro-

viding babysitters or driving the person to a doctor or lawyer. During the course of a year,

more than a million people are in hospice care in the United States. These services have

become so popular that two of five Americans receive hospice care prior to their deaths

(National Hospice 2008).

Whereas hospitals are dedicated to prolonging life, hospice care is dedicated to provid-

ing dignity in death and making people comfortable during the living–dying interval. In

the hospital, the focus is on the patient; in hospice care, the focus switches to both the

dying person and his or her friends and family. In the hospital, the goal is to make the pa-

tient well; in hospice care, it is to relieve pain and suffering and make death easier to bear.

In the hospital, the primary concern is the individual’s physical welfare; in hospice care,

although medical needs are met, the primary concern is the individual’s social—and, in

some instances, spiritual—well-being.

Suicide and Age

We noted in Chapter 1 how Durkheim stressed that suicide has a social base. Suicide,

he said, is much more than an individual act. Each country, for example, has its own

suicide rate, which remains quite stable year after year. In the United States, we can

predict that 31,000 people will commit suicide this year. If we are off by more than

1,000, it would be a surprise. As we saw in Figure 1.1 (page 13), we can also predict that

Americans will choose firearms as the most common way to kill themselves and that

hanging will come in second. We can also be certain that this year more men than

women will kill themselves, and more people in their 60s than in their 20s. It is this way

year after year.

Statistics often fly in the face of the impressions we get from the mass media, and here

we have such an example. Although the suicides of young people are given much public-

ity, such deaths are relatively rare. The suicide rate of adolescents is lower than that of

adults of any age. It is the elderly who have the highest suicide rate, especially those age

75 and over. Because adolescents have such a low overall death rate, however, suicide does

rank as their third leading cause of death—after accidents and homicide (Statistical Ab-

stract 2011:Table 118, 125).

These findings on suicide are an example of the primary sociological point stressed

throughout this text: Recurring patterns of human behavior—whether education, mar-

riage, work, crime, use of the Internet, or even suicide—represent underlying social forces.

Consequently, if no basic change takes place in the social conditions under which the

groups that make up U.S. society live, you can expect these same patterns of suicide to pre-

vail five to ten years from now.

Adjusting to Death

The feelings that people experience after the death of a loved one often surprise them.

Along with grief and loneliness, they may feel guilt, anger, or even relief. During the pe-

riod of mourning that follows, usually one or two years, the family members come to

terms with the death. In addition to sorting out their feelings, they also reorganize their

family system to deal with the absence of the person who was so important to it.

In general, when death is expected, family members find it less stressful. They have

begun to cope with the coming death by managing a series of smaller losses, includ-

ing the person’s inability to fulfill his or her usual roles or to do specific tasks. They

also have been able to say a series of goodbyes to their loved one. In contrast, unex-

pected deaths—accidents, suicides, and murders—bring greater emotional shock.

The family members have had no time to get used to the idea that the individual is

going to die. One moment, the person is here; the next, he or she is gone. The sud-

den death gave them no chance to say goodbye or to bring any form of “closure” to

their relationship.

390 Chapter 13 THE ELDERLY