Henslin James M. Sociology: A Down to Earth Approach

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

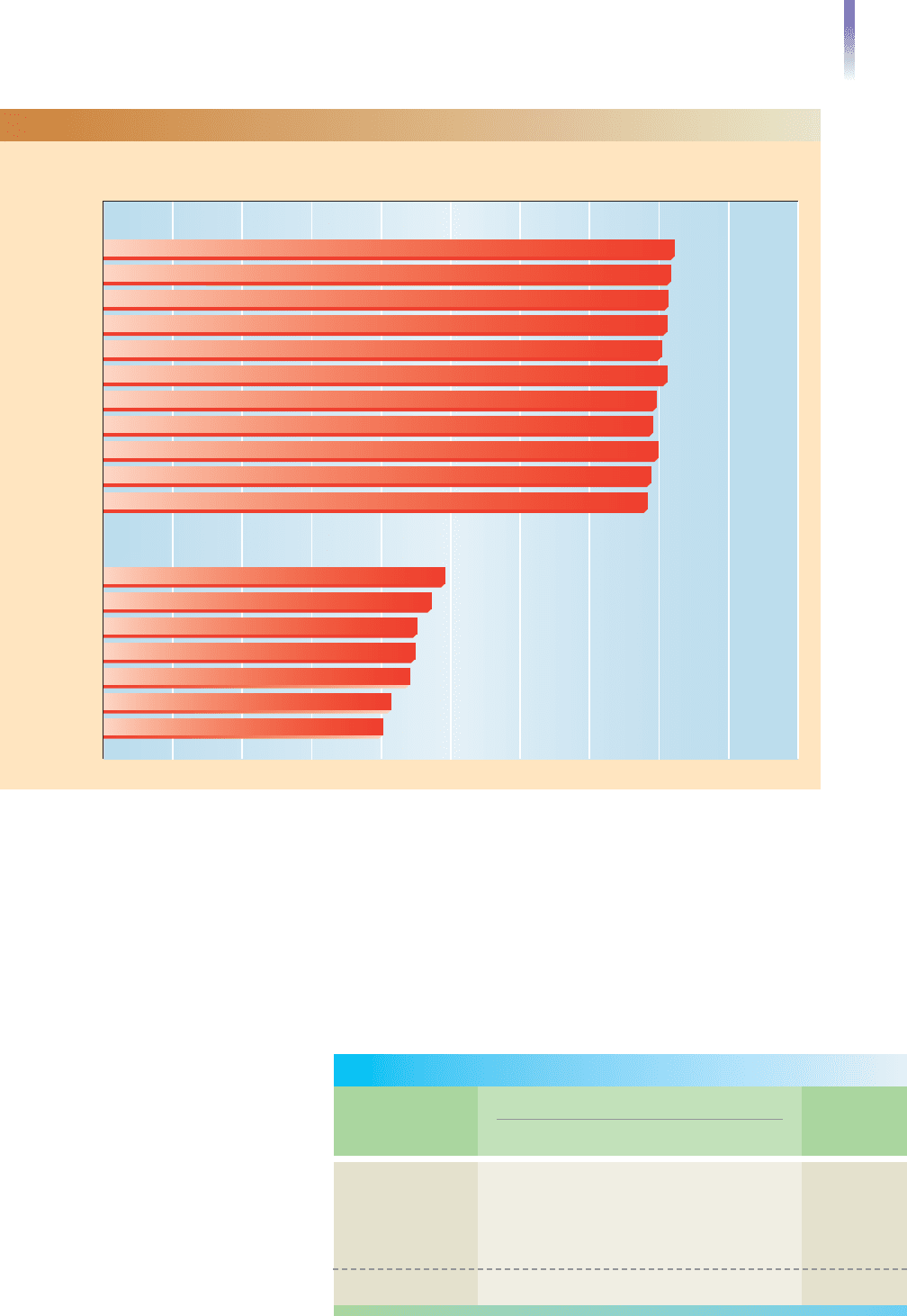

Abstract 2011:Table 7). Despite this vast change, as Figure 13.5 shows, life expectancy

in the United States is far from the world’s highest. With its overall average of 82,

Japan holds this record.

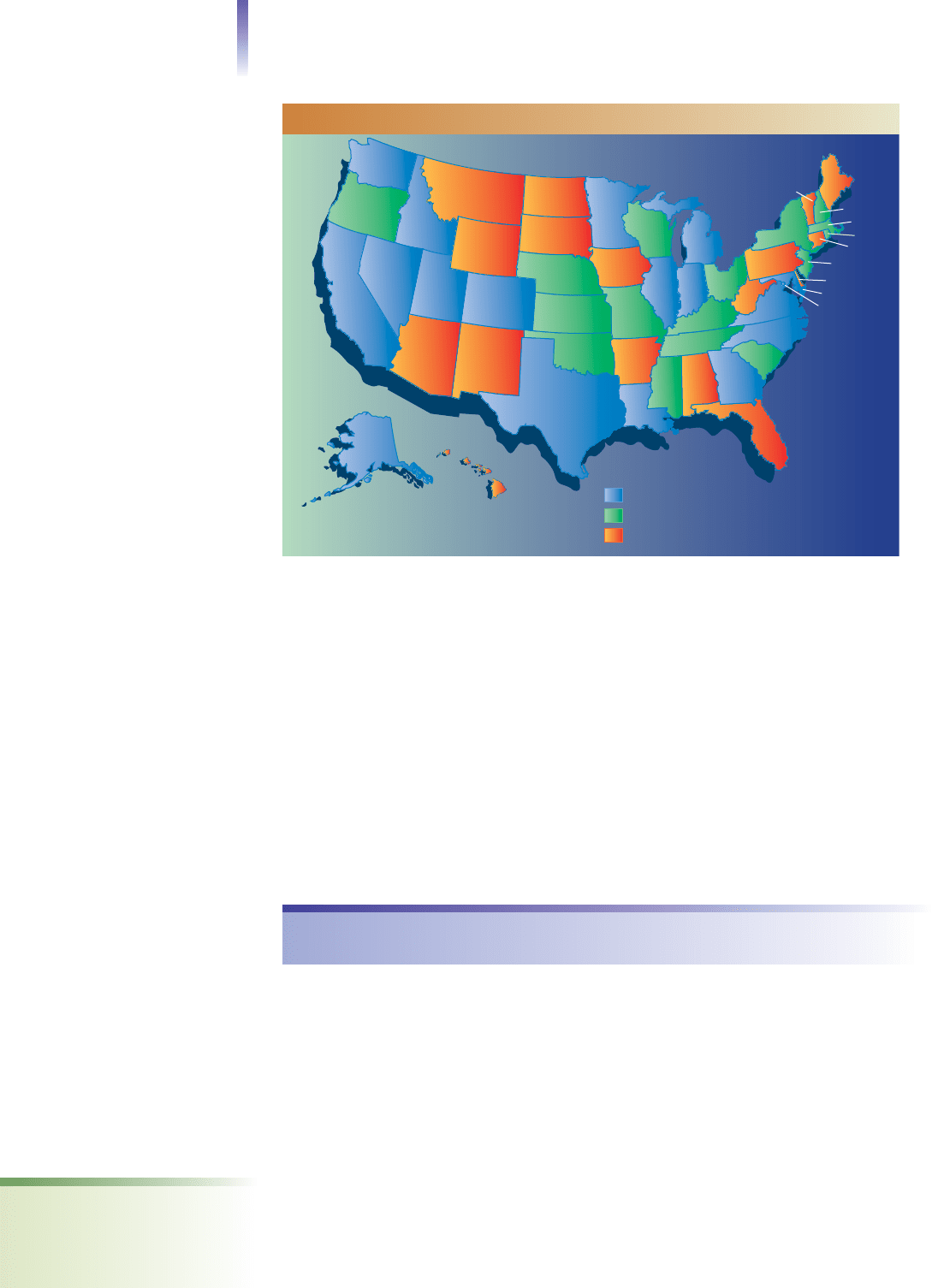

As anyone who has ever visited Florida

has noticed, the elderly population is not

distributed evenly around the country.

(As Jerry Seinfeld sardonically noted,

“There’s a law that when you get old,

you’ve got to move to Florida.”) The

Social Map on the next page shows how

uneven this distribution is.

Race–Ethnicity and Aging. Just as the

states have different percentages of elderly,

so do the racial–ethnic groups that make

up the United States. As you can see from

Table 13.1, whites have the highest percent-

age of elderly and Latinos the lowest. The

difference is so great that the proportion of

elderly whites (15.3 percent) is almost three

Aging in Global Perspective 371

Japan

Australia

Canada

France

Italy

Spain

Holland

Germany

Great Britain

South Korea

United States

South Africa

Nigeria

Afghanistan

Niger

Malawi

Mozambique

Zimbabwe

0

10 20 30 40 50

Years

60

70 80 90 100

82.2 years

The World’s Longest Life Expectancy (78 and higher)

The World’s Shortest Life Expectancy (below 50)

81.7 years

81.3 years

81.1 years

80.3 years

81.1 years

79.6 years

79.1 years

79.9 years

78.8 years

78.4 years

47.2 years

49.2 years

45.1 years

44.8 years

44.1 years

41.4 years

40.2 years

FIGURE 13.5 Life Expectancy in Global Perspective

Note: The countries listed in the source with a life expectancy higher than the United States and those with a life

expectancy less than 50 years. The totals are for year 2010. All the countries in the top group are industrialized, and none

of those in the bottom group is.

Source: By the author. Based on Statistical Abstract of the United States 2011:Table 1338.

TABLE 13.1 Race–Ethnicity and Aging

Total 65

and Over

AGE

Median 65–74 75–84 85⫹

Whites 41.2 8.2% 5.3% 2.2% 15.8%

Asian Americans 35.3 5.4% 3.0% 1.1% 9.6%

African Americans 31.3 4.9% 2.8% 0.9% 8.6%

Native Americans 29.5 4.4% 2.2% 0.7% 7.3%

Latinos 27.4 3.2% 1.8% 0.7% 5.7%

U.S.Average 36.8 6.7% 4.2% 1.8% 12.9%

Source: By the author. Based on Statistical Abstract of the United States 2011:Table 10.

times that of Latinos (5.5 percent). The percentage of older Latinos is small because so many

younger Latinos have migrated to the United States. Differences in cultural attitudes about

aging, family relationships, work histories, and health practices will be important areas of so-

ciological investigation in coming years.

Although more people are living to old age, the maximum length of life possible, the life

span, has not increased. No one knows, however, just what that maximum is. We do know

that it is at least 122, for this was the well-documented age of Jeanne Louise Calment of

France at her death in 1997. If the birth certificate of Tuti Yusupova in Uzbekistan proves to

be genuine, her age of 128 would indicate that the human life span may exceed even this num-

ber by a comfortable margin. It is also likely that advances in genetics will extend the human

life span—perhaps to hundreds of years—a topic we will return to later. For now, let’s see the

different pictures of aging that emerge when we apply the three theoretical perspectives.

The Symbolic Interactionist Perspective

We saw how industrialization changed the way earlier Americans viewed the elderly. To

see how social factors affect our own views, let’s begin by asking how culture “signals” to

people that they are “old.” Then let’s consider how ideas about the elderly are changing

and how stereotypes and the mass media influence our perceptions of aging.

When Are You “Old”?

Changing Perceptions as You Age. You probably can remember when you thought that

a 12-year-old was “old”—and anyone older than that, beyond reckoning. You probably

were 5 or 6 at the time. Similarly, to a 12-year-old, someone who is 21 seems “old.” To

someone who is 21, 30 may mark the point at which one is no longer “young,” and 40

may seem very old. As people add years, “old” gradually recedes further from the self. To

people who turn 40, 50 seems old; at 50, the late 60s look old—not the early 60s, for the

passing of years seems to accelerate as we age, and at 50 age 60 doesn’t seem so far away.

In Western culture, most people have difficulty applying the label “old” to themselves.

In the typical case, they have become used to what they see in the mirror. The changes

372 Chapter 13 THE ELDERLY

AK

VT

The younger states: 10.1% to 14.2%

The average states: 14.4% to 15.7%

The grayer states: 15.8% to 19.5%

UT

OH

SC

NC

VA

WA

OR

CA

NV

ID

MT

WY

AZ

NM

CO

ND

SD

NE

KS

OK

TX

MN

IA

MO

AR

LA

WI

IL

KY

TN

MS

AL

GA

FL

IN

MI

WV

PA

NY

ME

NH

MA

RI

CT

NJ

DE

MD

DC

HI

Percent Elderly

FIGURE 13.6 As Florida Goes, So Goes the Nation

Source: By the author. Based on Statistical Abstract of the United States 2011:Table 18. Projections

to 2015.

life span the maximum length

of life of a species; for humans,

the longest that a human has

lived

have taken place gradually, and each change, if it

has not exactly been taken in stride, has been ac-

commodated. Consequently, it comes as a shock

to meet a long-lost friend and see how much that

person has changed. At class reunions, each per-

son can hardly believe how much older the others

appear!

Four Factors in Our Decision. If there is no

fixed age line that people cross, then what makes

someone “old”? Sociologists have identified sev-

eral factors that spur people to apply the label

of old to themselves.

The first factor is biology. One person may ex-

perience “signs” of aging earlier than others: wrin-

kles, balding, aches, difficulty in doing something

that he or she used to take for granted. Conse-

quently, one person will feel “old” at an earlier or

later age than others.

A second factor is personal history or biogra-

phy. An accident that limits someone’s mobility,

for example, can make that person feel old sooner

than others. Or consider a woman who gave birth

at 16 and has a daughter who, in turn, has a child

at 18. She has become a biological grandmother at age 34. It is most unlikely, however, that

she will play any stereotypical role—spending the day in a rocking chair, for example—but

knowing that she is a grandmother has an impact on her self-concept. At a minimum, she

must deny that she is old.

Then there is gender age, the relative value that a culture places on men’s and women’s

ages. For example, graying hair on a man, and even a few wrinkles, may be perceived as

signs of “maturity,” while on a woman, those same features may indicate that she is getting

“old.” “Mature” and “old,” of course, carry different meanings; most of us like to be called

mature, but few of us like to be called old. Similarly, around the world, most men are able

to marry younger spouses than women can. Maria might be an exception and marry Bill,

who is fourteen years younger than she. But in most marriages in which there is a fourteen-

year age gap, the odds greatly favor the wife being the younger of the pair. This is not bi-

ology in action; rather, it is the social construction of appearance and gender age.

The fourth factor in deciding when people label themselves as “old” is timetables, the

signals societies use to inform their members that old age has begun. Since there is no au-

tomatic age at which people become “old,” these timetables vary around the world. One

group may choose a particular birthday, such as the 60th or 65th, to signal the onset of

old age. Other groups do not even have birthdays, making such numbers meaningless. In

the West, retirement is sometimes a cultural signal of the beginning of old age—which is

one reason that some people resist retirement.

Changing Perceptions of the Elderly

At first, the audience sat quietly as the developers explained their plans to build a high-rise

apartment building. After a while, people began to shift uncomfortably in their seats. Then

they began to show open hostility.

“That’s too much money to spend on those people,” said one.

“You even want them to have a swimming pool?” asked another incredulously.

Finally, one young woman put their attitudes in a nutshell when she asked, “Who wants

all those old people around?”

When physician Robert Butler (1975, 1980) heard these complaints about plans to build

apartments for senior citizens, he began to realize how deeply antagonistic feelings toward the

elderly can run. He coined the term ageism to refer to prejudice, discrimination, and hostil-

ity directed against people because of their age. Let’s see how ageism developed in U.S. society.

The Symbolic Interactionist Perspective 373

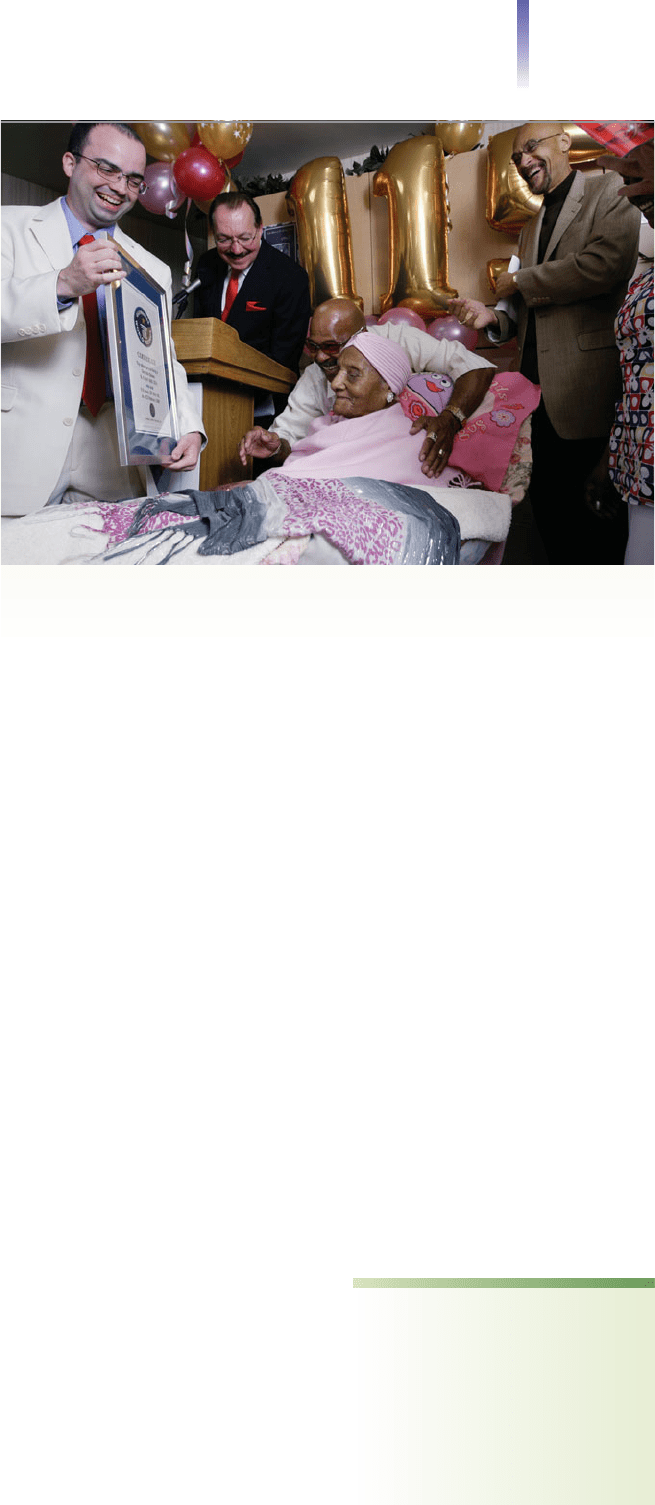

At age 115, Gertrude Baines is the world’s oldest living person. Baines, whose

parents were former slaves, was born in Georgia in 1894. The world’s record for

age that has been documented by a birth certificate is held by Jeanne Calment

of France who died in 1997 at the age of 122.

gender age the relative value

placed on men’s and women’s

ages

ageism prejudice, discrimina-

tion, and hostility directed

against people because of their

age; can be directed against any

age group, including youth

Shifting Meanings. As we have seen, there is nothing inherent in old

age to produce any particular attitude, negative or not. Some histori-

ans point out that in early U.S. society old age was regarded positively

(Cottin 1979; Fleming et al. 2003). In colonial times, growing old was

seen as an accomplishment because so few people made it to old age.

With no pensions, the elderly continued to work at jobs that changed

little over time. They were viewed as storehouses of knowledge about

work skills and sources of wisdom about how to live a long life.

The coming of industrialization eroded these bases of respect. The

better sanitation and medical care allowed more people to reach old

age, and no longer was being elderly an honorable distinction. In-

dustrialization’s new forms of mass production also made young

workers as productive as the elderly. Coupled with mass education,

this stripped away the elderly’s superior knowledge (Cowgill 1974;

Hunt 2005). In the Cultural Diversity box on the next page, you can

see how a similar process is now occurring in China as it, too, indus-

trializes.

A basic principle of symbolic interactionism is that we perceive

both ourselves and others according to the symbols of our culture.

What old age means to people has followed this principle. When the

meaning of old age changed from an asset to a liability, not only did

younger people come to view the elderly differently but the elderly

also began to perceive themselves in a new light. This shift in mean-

ing is demonstrated in the way people lie about their age: They used

to claim that they were older than they were, but now they say that

they are younger than they are (Clair et al. 1993).

Once again, the meaning of old age is shifting—and this time in

a positive direction. This is largely because most of today’s U.S. eld-

erly can take care of themselves financially, and many are well-off. As

the vast numbers of the baby boom generation enter their elderly

years, their better health and financial strength will contribute to still

more positive images of the elderly. If this symbolic shift continues,

the next step—now in process—is to celebrate old age as a time of re-

newal. Old age will be viewed not as a period that precedes death,

but, rather, as a new stage of growth.

Even in scholarly theories, perceptions of the elderly have become

more positive. A theory that goes by the mouthful gerotranscendence was developed by

Swedish sociologist Lars Tornstam. The thrust of this theory is that as people grow old they

transcend their more limited views of life. They become less self-centered and begin to feel

more at one with the universe. Coming to see things as less black and white, they develop

more subtle ways of viewing right and wrong and tolerate more ambiguity (Manheimer

2005; Wadensten 2007). This theory is not likely to be universal. I have seen some eld-

erly people grow softer and more spiritual, but I have also seen others grow bitter, close

up, and become even more judgmental of others. The theory’s limitations should become

apparent shortly.

374 Chapter 13 THE ELDERLY

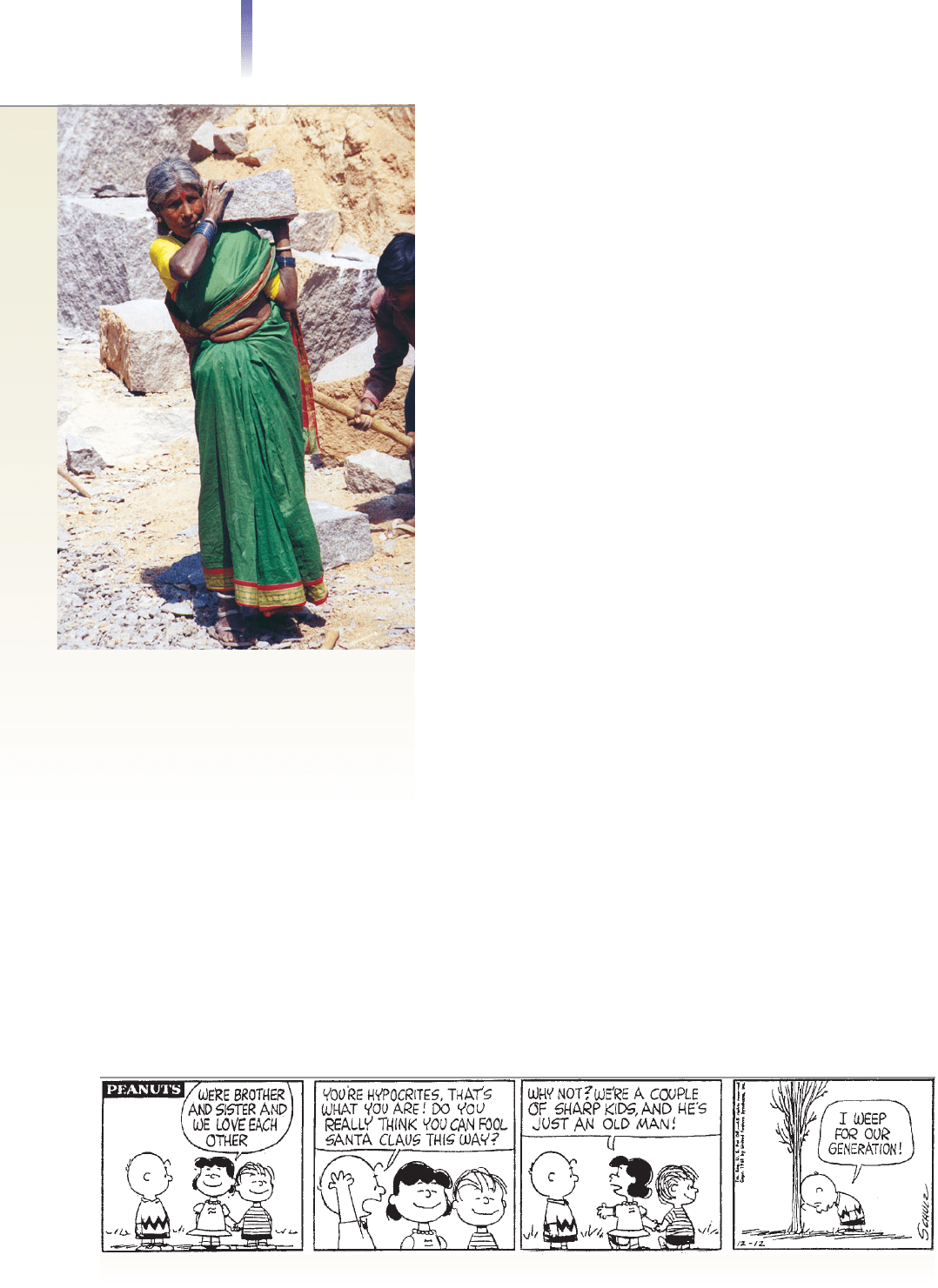

When does old age begin? And what activities are

appropriate for the elderly? From this photo that I took

of Munimah, a 65-year-old bonded laborer in Chennai,

India, you can see how culturally relative these questions

are. No one in Chennai thinks it is extraordinary that

this woman makes her living by carrying heavy rocks all

day in the burning, tropical sun.Working next to her in

the quarry is her 18-year-old son, who breaks the rocks

into the size that his mother carries.

Stereotypes, which play such a profound role in social life, are a basic area of sociological investigation. In

contemporary society, the mass media are a major source of stereotypes.

The Symbolic Interactionist Perspective 375

Cultural Diversity around the World

China: Changing Sentiment

About the Elderly

A

s she contemplates her future, Zhao Chunlan, a

71-year-old widow, smiles shyly, with evident

satisfaction. She has heard about sons abandon-

ing their aged parents. She has even

heard whispering about abuse.

But Zhao has no such fears.

It is not that her son is so devoted

that he would never swerve from his

traditional duty to his mother. Rather,

it is a piece of paper that has eased

Zhao’s mind. Her 51-year-old son has

signed a support agreement: He will

cook her special meals, take her to

medical checkups, even give her the

largest room in his house and put the

family’s color television in it (Sun 1990).

The high status of the elderly in

China is famed around the world: The

elderly are considered a source of wis-

dom, given honored seating at both

family and public gatherings—even ven-

erated after death in ancestor worship.

Although this outline may represent

more ideal than real culture, it appears

to generally hold true—for the past,

that is. Today, the authority of elders has

eroded, leading to less respect from the

adult children (Yan 2003; Fan 2008). For some, the cause is

the children’s success in the new market economy, which

places them in a world unknown to their parents (Chen

2005). But other structural reasons are also tearing at the

bonds between generations, especially the longer life ex-

pectancy that has come with industrialization. The change

is startling: In 1950, China’s life expectancy was 41 years.

It has now jumped to 70 years (Li 2004). China’s elderly

population is growing so rapidly that the

country has 114 million elderly—8.6

percent of its population (Statistical Abstract

2011:Table 1333).

China’s policy that allows each married couple only

one child has created a problem for the support of the

elderly. With such small families, the responsibility for

supporting aged parents falls on

fewer shoulders. The problem is

that many younger couples must

now support four elderly parents

(Zhang and Goza 2007). Try put-

ting yourself in that situation, and

see how it would interfere with

your plans for life. Can you see

how it might affect your attitudes

toward your aging parents—and

toward your in-laws?

Alarmed by signs that parent–

child bonds are weakening, some

local officials require adult children

to sign support agreements for

their aged parents. One province

has come up with an ingenious de-

vice: To get a marriage license, a

couple must sign a contract pledg-

ing to support their parents after

they reach age 60 (Sun 1990).“I’m

sure he would do right by me, any-

way,” says Zhao,“but this way I

know he will.”

For Your Consideration

Do you think we could solve our Social Security crisis

by requiring adult children to sign a parental support

agreement in order to get a marriage license? Why or

why not? What do you think Chinese officials can do to

solve the problem of supporting these huge and grow-

ing numbers?

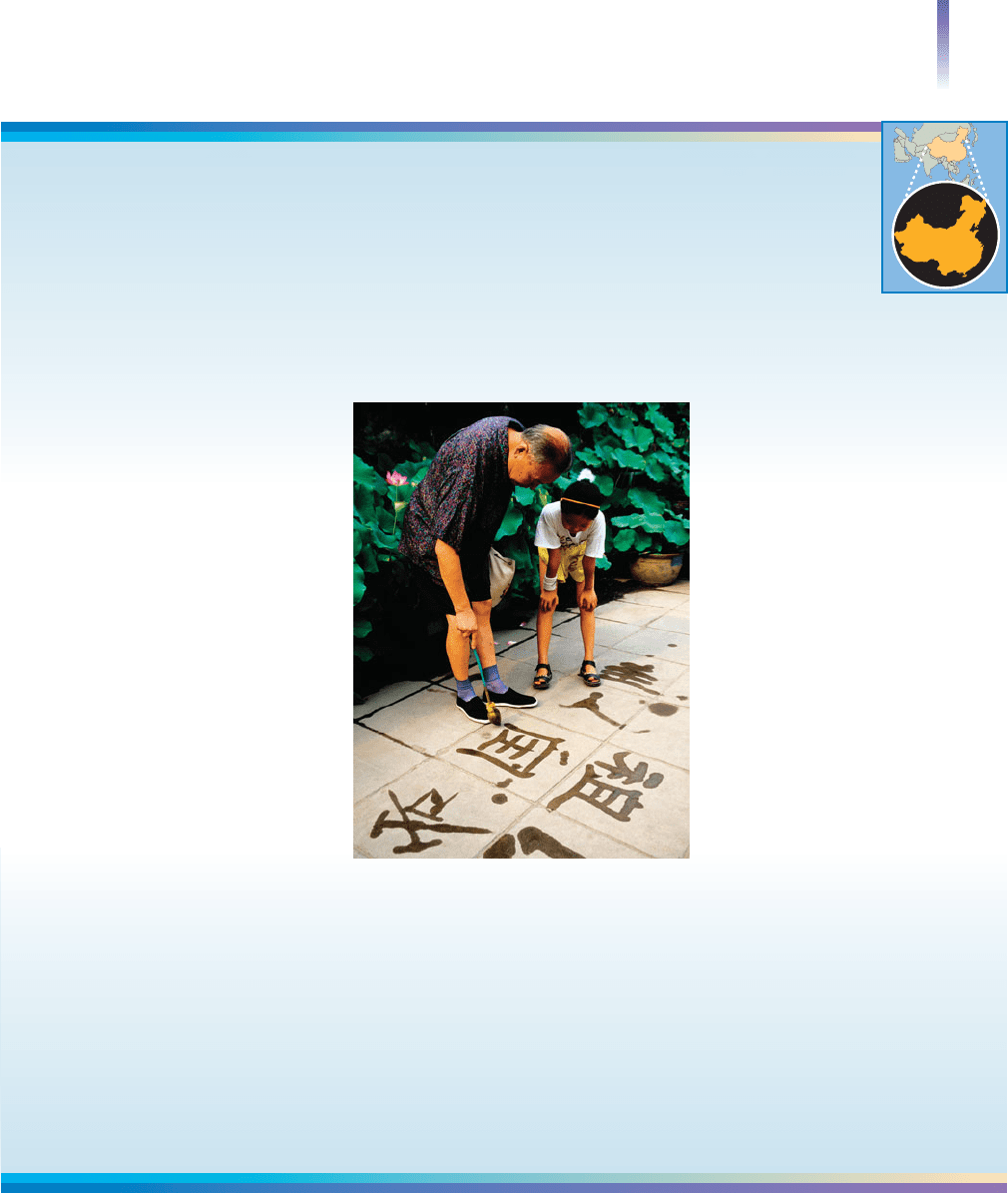

This grandfather in Beijing is teaching calligraphy

to his granddaughter. As China industrializes and

urbanizes, its society is changing, including the

structure of relationships that nurture the elderly.

China

China

The Influence of the Mass Media

In Chapter 3 (pages 78–80), we noted that the mass media help to shape our ideas about both

gender and relationships between men and women. As a powerful source of symbols, the

media also influence our ideas of the elderly, the topic of the Mass Media box on the next page.

In Sum: Symbolic interactionists stress that old age has no inherent meaning. There

is nothing about old age to automatically summon forth responses of honor and re-

spect, as with the Abkhasians, or any other response. Culture shapes how we perceive

the elderly, including the way we view our own aging. In short, the social modifies the

biological.

376 Chapter 13 THE ELDERLY

MASS MEDIA In

SOCIAL LIFE

The Cultural Lens: Shaping Our

Perceptions of the Elderly

T

he mass media profoundly influence our percep-

tion of others.What we hear and see on televi-

sion and in the movies, the songs we listen to, the

books and magazines we read—all become part of the

cultural lens through which we view the world. Without

our knowing it, the media subtly shape our images of

people. They influence how we view minorities and dom-

inant groups; men, women, and children; people with dis-

abilities; people from other cultures—and the elderly.

The shaping of our images and perception of the eld-

erly is subtle, so much so that it usually occurs without

our awareness. The elderly, for example, are underrep-

resented on television and in most popular magazines.

This leaves a covert message—that the elderly are of lit-

tle consequence and can be safely ignored.

The media also reflect and reinforce stereotypes of

gender age. Older male news anchors are likely to be re-

tained, while female anchors who turn the same age are

more likely to be transferred to less visible positions.

Similarly, in movies older men are more likely to play ro-

mantic leads—and to play them opposite much younger

rising stars.

Although usually subtle, the message is not lost. The

more television that people watch, the more they per-

ceive the elderly in negative terms. The elderly, too, in-

ternalize these negative images, which, in turn, influences

the ways they view themselves. These images are so

powerful that they affect the elderly’s health, even the

way they walk (Donlon et al. 2005).

We become fearful of growing old, and we go to

great lengths to deny that this is happening to us. Fear

and denial play into the hands of advertisers, of course,

who exploit our concerns about losing our youth.

They help us deny this biological reality by selling us hair

dyes, skin creams, and other products that are designed

to conceal even the appearance of old age. For these

same reasons, plastic surgeons do a thriving business as

they remove telltale signs of aging.

The elderly’s growing numbers and affluence translate

into economic clout and political power. It is inevitable,

then, that the media’s images of the elderly will change.

An indication of that change is shown in the photo above.

For Your Consideration

What other examples of fear and denial of growing old

are you familiar with? What examples of older men play-

ing romantic leads with younger women can you give?

Of older women and younger men? Why do you think

we have gender age?

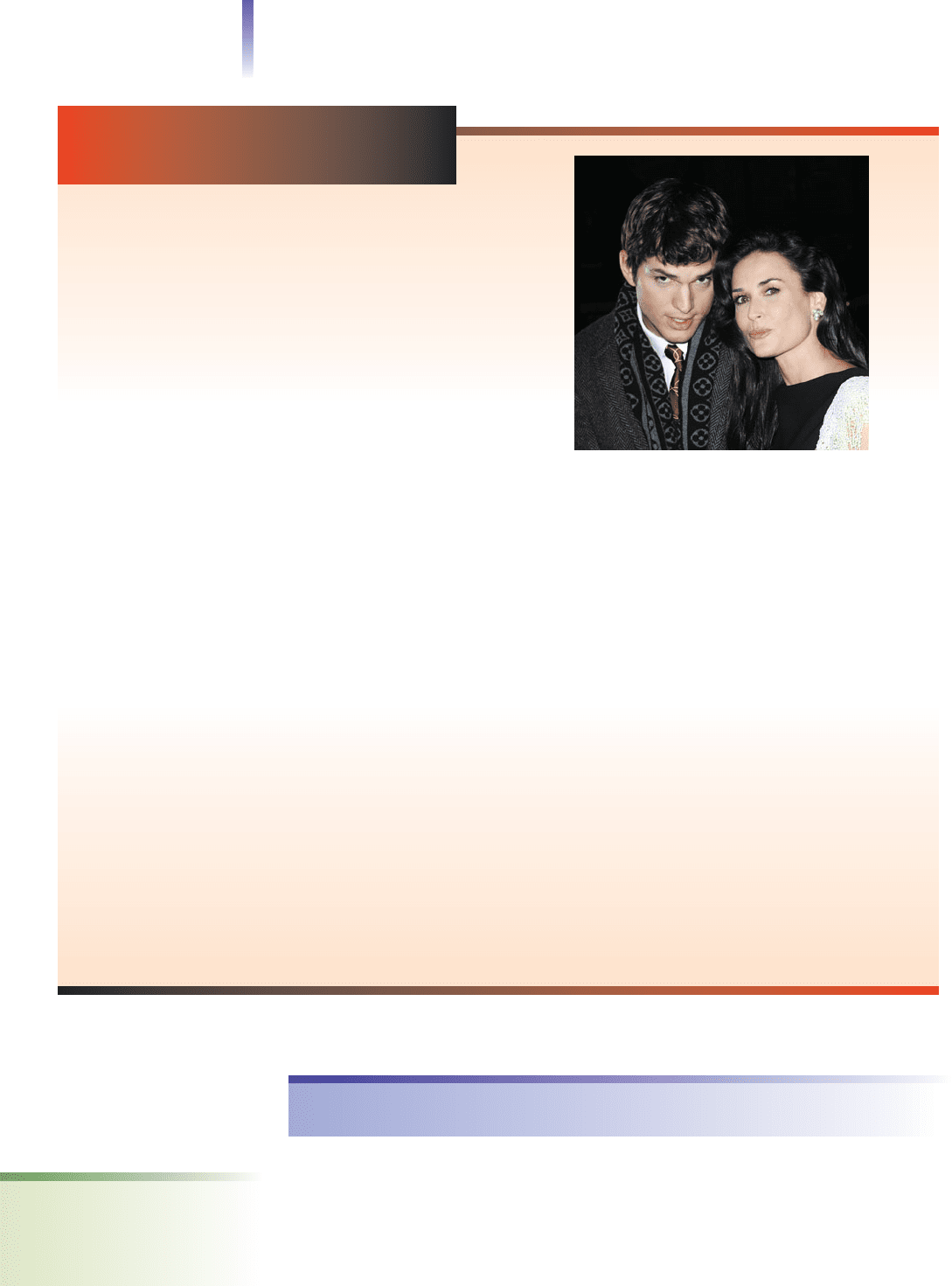

In some cultures, Demi Moore, 44, would be con-

sidered elderly. Moore is shown here with her hus-

band, Ashton Kutcher, 29. Almost inevitably,

when there is a large age gap between a husband

and wife, it is the husband who is the older one.

The marriage of Kutcher and Moore is a reversal

of the typical pattern of gender age.

The Functionalist Perspective

Functionalists analyze how the parts of society work together. Among the components of

society are age cohorts—people who were born at roughly the same time and who pass

through the life course together. Although you don’t see them, age cohorts have a huge

impact on your life. When you finish college, for example, if the age cohort nearing re-

tirement is large (a “baby boom” generation), more jobs will be available. In contrast, if

it is a small group (a “baby bust” generation), fewer jobs open up. Let’s look at theories

that focus on how people adjust to retirement.

age cohort people born at

roughly the same time who

pass through the life course

together

Disengagement Theory

Think about how disruptive it would be if the elderly left their jobs only when they died

or became incompetent. How does society get the elderly to leave their positions so

younger people can take them? According to disengagement theory, developed by Elaine

Cumming and William Henry (1961), this is the function of pensions. Pensions get the

elderly to disengage from their positions and hand them over to younger people. Retire-

ment, then, is a mutually beneficial arrangement between two parts of society.

Cumming (1976) also examined disengagement from the individual’s perspective.

She pointed out that people start to disengage long before retirement. During middle

age, they sense that the end of life is closer than its start. As they realize that their time

is limited, they begin to assign priority to goals and tasks. Disengagement begins in

earnest when their children leave home and increases with retirement and eventually

widowhood.

Changing Forms of “Disengagement.” And how do the elderly “disengage” today? Few quit

their jobs and sit in rocking chairs watching the world go by. With computers, the Internet,

and new types of work, the dividing line between work and retirement has blurred. Less

and less does retirement mean an end to work. Millions of workers just slow down. Some

stay at their jobs, but put in fewer hours. Others work as consultants part-time. Some switch

careers, even though they are in their 60s, some even in their 70s. Many never “retire”—at

least not in the sense of sinking into a recliner or being forever on the golf course.

Evaluation of the Theory. Disengagement theory came under attack almost as soon as

the ink dried on the theorists’ paper. One of the main criticisms is that this theory con-

tains an implicit bias against older people—assumptions that the elderly disengage from

productive social roles and then sort of slink into oblivion (Manheimer 2005). Instead of

disengaging, say the critics, the elderly exchange one set of roles for another (Jerrome

1992). The elderly’s new roles, which often center on friendship, are no less satisfying to

them than their earlier roles. These new roles are less visible to researchers, however, who

tend to have a youthful orientation—and who show their bias by assuming that produc-

tivity is the measure of self-worth. If disengagement theory is ever resurrected, it must also

come to grips with our new patterns of “disengagement.”

Activity Theory

Are retired people more satisfied with life?

(All that extra free time and not having to

kow-tow to a boss must be nice.) Are intimate

activities more satisfying than formal ones?

Such questions are the focus of activity the-

ory. Although we could consider this theory

from other perspectives, we are examining it

from the functionalist perspective because its

focus is how disengagement is functional or

dysfunctional.

Evaluation of the Theory. A study of retired

people in France found that some people are

happier when they are more active, but others

are happier when they are less involved (Keith

1982). Similarly, most people find informal,

intimate activities, such as spending time with

friends, to be more satisfying than formal

activities. But not everyone does. In one

study, 2,000 retired U.S. men reported for-

mal activities to be as important as informal

ones. Even solitary activities, such as doing

home repairs, had about the same impact as

The Functionalist Perspective 377

disengagement theory the

view that society is stabilized

by having the elderly retire

(disengage from) their posi-

tions of responsibility so the

younger generation can step

into their shoes

activity theory the view that

satisfaction during old age is re-

lated to a person’s amount and

quality of activity

Researchers are exploring factors that can make old age an enjoyable period of life,

those conditions that increase people’s mental, social, emotional, and physical well-

being. As research progresses, do you think we will reach the point where the

average old person will be in this woman’s physical condition?

intimate activities on these men’s life satisfaction (Beck and Page 1988). It is the same for

spending time with adult children. “Often enough” for some parents is “not enough” or

even “too much” for others. In short, researchers have discovered the obvious: What makes

life satisfying for one person doesn’t work for another. (This, of course, can be a source of

intense frustration for retired couples.)

Continuity Theory

Another theory of how people adjust to growing old is continuity theory. As its name im-

plies, the focus of this theory is on how the elderly maintain ties with their past (Kinsella

and Phillips 2005). When they retire, many people take on new roles that are similar to

the ones they gave up. For example, a former CEO might serve as a consultant, a retired

electrician might do small electrical repairs, or a pensioned banker might take over the fi-

nances of her church. Researchers have found that people who are active in multiple roles

(wife, author, mother, intimate friend, church member, etc.) are better equipped to han-

dle the changes that growing old entails. They have also found that with their greater re-

sources, people from higher social classes adjust better to the challenges of aging.

Evaluation of the Theory. The basic criticism of continuity theory is that it is too broad

(Hatch 2000). We all have anchor points based on our particular experiences in life, and

we all rely on them to make adjustments to the changes we encounter. This applies to peo-

ple of all ages beyond infancy. This theory is really a collection of loosely connected ideas,

with no specific application to the elderly.

In Sum: The broader perspective of the functionalists is how society’s parts work together

to keep society running smoothly. Although it is inevitable that younger workers replace

the elderly, this transition could be disruptive. To entice the elderly out of their positions

so that younger people can take over, the elderly are offered pensions. Functionalists also

use a narrower perspective, focusing on how individuals adjust to their retirement. The

findings of this narrower perspective are too mixed to be of much value—except that peo-

ple who have better resources and are active in multiple roles adjust better to old age

(Crosnoe and Elder 2002).

Because U.S. workers do not have to retire by any certain age, it is also important to study

how people decide to keep working or to retire in the first place. After they retire, how do they

reconstruct their identities and come to terms with their changed life? As the United States

grows even grayer, these should prove productive areas of sociological theory and research.

The Conflict Perspective

As you know, the conflict perspective’s guiding principle of social life is how social groups

struggle to control power and resources. How does this apply to society’s age groups? Re-

gardless of whether the young and old recognize it, say conflict theorists, they are oppo-

nents in a struggle that threatens to throw society into turmoil. Let’s look at how the

passage of Social Security legislation fits the conflict view.

Fighting for Resources: Social Security Legislation

In the 1920s, before Social Security provided an income for the aged, two-thirds of all cit-

izens over 65 had no savings and could not support themselves (Holtzman 1963; Crossen

2004a). The fate of workers sank even deeper during the Great Depression, and in 1930

Francis Townsend, a physician, started a movement to rally older citizens. He soon had

one-third of all Americans over age 65 enrolled in his Townsend Clubs. They demanded

that the federal government impose a national sales tax of 2 percent to provide $200 a

month for every person over 65 ($2,100 a month in today’s money). In 1934, the

Townsend Plan went before Congress. Because it called for such high payments and many

were afraid that it would destroy people’s incentive to save for the future, members of

378 Chapter 13 THE ELDERLY

continuity theory the focus

of this theory is how people

adjust to retirement by contin-

uing aspects of their earlier

lives

Congress looked for a way to reject the plan without appearing to oppose the elderly.

When President Roosevelt announced his own, more modest Social Security plan in 1934,

Congress embraced it (Schottland 1963; Amenta 2006).

To provide jobs for younger people, the new Social Security law required that work-

ers retire at age 65. It did not matter how well people did their work, or how much they

needed the pay. For decades, the elderly protested. Finally, in 1986, Congress eliminated

mandatory retirement. Today, almost 90 percent of Americans retire by age 65, but most

do so voluntarily. No longer can they be forced out of their jobs simply because of their

age. Let’s look at what has happened to this groundbreaking legislation since it was

passed.

The Conflict Perspective 379

ThinkingCRITICALLY

The Social Security Trust Fund: There Is No Fund,

and You Can’t Trust It

E

ach month, the Social Security Administration mails checks to 50 million people.

Across the country, 205 million U.S. workers pay into the Social Security system, look-

ing to it to provide for their basic necessities—and even a little more than that—in

their old age (Statistical Abstract 2011:Tables 542, 543).

How dependable is Social Security? The short answer is “Don’t bet your old age on it.”

The first problem is well known. Social Security is not a bank account. The money taken

from our checks is not deposited into our individual accounts. No money in the Social Se-

curity system is attached to anyone’s name. At retirement, we don’t withdraw the money

we paid into Social Security. Instead, the government writes checks on money that it col-

lects from current workers. When these workers retire, they, too, will be paid, not from

their own savings, but from money collected from others who are still working.

The Social Security system is like a giant chain letter—it works as long as enough new

people join the chain. If you join early enough, you’ll collect more than you paid in—but if

you join toward the end, you’re sim-

ply out of luck.And, say some con-

flict theorists, we are nearing the

end of the chain.The shift in the

dependency ratio—the number

of people who collect Social Secu-

rity compared with the number of

workers who contribute to it—is

especially troubling.As Figure 13.7

shows, sixteen workers used to

support each person who was col-

lecting Social Security. Now the

dependency ratio has dropped to

four to one. In another generation,

it could hit two to one. If this hap-

pens, Social Security taxes could

become so high that they stifle the

country’s economy.To prevent

this, Congress raised Social Secu-

rity taxes and established a Social

Security trust fund. Supposedly,

this fund has trillions of dollars.

But does it?

16

4

2?

1950

2000

2030

Number of workers

who pay into Social

Security for each

beneficiary

FIGURE 13.7 Fewer Workers

to Support the Retired

Source: By the author. Based on Social Security

Administration; Statistical Abstract of the United States

2011:Tables 542, 543.

dependency ratio the num-

ber of workers who are

required to support each

dependent person—those 65

and older and those 15 and

under

380 Chapter 13 THE ELDERLY

This question takes us to the root of the crisis, or, some would say, the fraud. In 1965, Pres-

ident Lyndon Johnson was bogged down in a war in Vietnam. To conceal the war’s costs from

the public, he arrived at the diabolical solution of forcing the Social Security Administration to

invest only in U.S.Treasury bonds, a form of government IOUs. This put the money collected

for Social Security into the general fund, where Johnson could siphon it off to finance the war.

Politicians love this easy source of money, and they continue the fraud. They use the term “off

budget” to refer to the Social Security money they spend. And each year, they spend it all.

Suppose that you buy a $10,000 U.S. Treasury bond. The government takes your

$10,000 and hands you a document that says it owes you $10,000 plus interest. This is how

Social Security works. The Social Security Administration (SSA) collects the money from

workers, pays the retired, disabled, and survivors of deceased workers, and then hands the

excess over to the U.S. government. The government, in turn, gives IOUs to the SSA in the

form of U.S.Treasury bonds. The government spends the money on whatever it wants—

whether that means building roads and schools, subsidizing tobacco crops, or buying bombs

and fighting a war in some far off place.

Suppose you are spending more money than you make. You talk Aunt Mary into loaning

you some money, and you give her an IOU. If you don’t count what you owe Aunt Mary, you

have a surplus. The government simply does not count those huge IOUs that it owes the

elderly. Instead, it reports a fake surplus to the public.

This arrangement is a politician’s dream. Politicians grab the money from the workers and

hand the workers giant IOUs. And then they pretend that they haven’t even spent that money.

The Gramm-Rudman law, which was designed to limit the amount of federal debt, does

not count the money that the government “borrows” from Social Security. It is as though

the debt owed to Social Security does not exist—and to politicians it doesn’t. To politicians,

Social Security is a magical money machine. A wave of their magical wand produces billions

from thin air. Are those just numbers on paper? Or are they money that has been confis-

cated from workers? Ask workers whose paychecks are hit by that magical wand.

One analyst (Sloan 2001) put the matter pithily:“The Social Security trust fund isn’t

a fund, and you shouldn’t trust it.”

For Your Consideration

Here are two proposals to solve this problem.

1. Raise the age at which Social Security payments begin to 70.

2. Keep the retirement age the same, but put what workers pay as Social Security taxes

into their own individual retirement accounts. Most proposals to do this lack controls to

make the system work. Here are controls:A board, independent of the government,

would select money managers to invest these accounts in natural resources, real estate,

stocks, and bonds—both foreign and domestic.Annually, the board would review the

performance of each money manager, retaining those who do the best job and replacing

the others. All investment results would be published, and individuals could select the

management team that they prefer. No one could withdraw funds before retirement.

How about your own Social Security? Do you prefer to retain the current system? Do

you prefer one of these two proposals? Neither is perfect. What problems might each have?

Can you think of a better alternative?

Sources: Smith 1986; Hardy 1991; Genetski 1993; Stevenson 1998; Statistical Abstract 2011. Government publications

that list Social Security receipts as deficits can be found in Monthly Treasury Statement of Receipts and Outlays, the

Winter Treasury Bulletin, and the Statement of Liabilities and Other Financial Commitments of the United States Government.

Intergenerational Competition and Conflict

Social Security came about not because the members of Congress had generous hearts, but

out of a struggle between competing interest groups. As conflict theorists stress, equilib-

rium between competing groups is only a temporary balancing of oppositional forces,