Elsevier Encyclopedia of Geology - vol I A-E

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

generated by underplating of mantle-derived melts.

However, there is little geophysical evidence for

lower crustal mafic intrusions in this area. In the cen-

tral and eastern North Sea, Denmark, and the Skager-

rak Graben, geophysical evidence such as deep crustal

reflectors and Bouguer anomalies suggest that, here,

volcanism may have been accompanied by crustal

underplating, although the age of these features

remains uncertain.

The effects of Permo-Carboniferous magmatism at

various crustal levels can be studied exemplarily in

the Ivrea Zone of northern Italy. This tilted crustal

fragment provides one of the rare opportunities in the

world to study a coherent crustal succession from

the Moho to upper crustal levels. The Ivrea Zone

achieved its present structure largely at the end

and shortly after the Variscan Orogeny. Intrusion of

mantle-derived basic magmas at or near the base of

the crust caused partial melting of lower crustal

rocks. This in turn generated granitic magmas that

ascended to middle and upper crustal levels. At the

surface, magmatism is also documented by volcanic

activity in the contemporaneous sedimentary basins.

Geodynamic Setting and Driving

Forces for Extension

The geodynamic setting of the Variscan domain

during the Permo-Carboniferous and the driving

forces for crustal re-equilibration have been matters

of intense debate. A prime feature is the strong ther-

mal perturbation of the lithosphere, which has been

attributed to diverse processes such as slab detach-

ment, delamination and thermal erosion of the

mantle lithosphere, crustal extension, or ascent of

mantle plumes. Some explanations even manage with-

out substantial crustal extension and assume eclogiti-

zation of the lower crust as the main process for the

disappearance of the Variscan crustal roots. In this

respect, it is interesting to note that basin formation

and substantial magmatism occur also in the northern

foreland of the Variscides (i.e., in an area not affec-

ted by Variscan crustal and lithospheric thickening).

Thus, the processes often invoked for postconvergent

settings may not hold in these areas. This leads to the

fundamental question: were Permo-Carboniferous

basin formation and magmatism genetically linked to

the preceding Variscan Orogeny, or do they document

a new geodynamic regime?

Because of the close temporal and spatial relation-

ship between crustal thickening and postconvergent

extension, several authors have suggested a gravita-

tional collapse of the Variscan orogen as the domin-

ant process controlling the geodynamic evolution of

central Europe in latest Carboniferous to Permian

times. The Tibetan Plateau of China and the Basin

and Range Province of the United States have been

proposed as modern analogues for theLate Palaeozoic

destruction of the Variscan orogen. Other authors,

however, have suggested that the postconvergent de-

struction of the Variscides was caused primarily not

by body forces, but by a change in orientation of the

far-field stress regime. The onset of the Stephanian

to Early Permian basin formation indeed coincides

with the change in the relative movement between

Gondwana and Laurussia, from head-on collision to

dextral translation.

To solve this dispute, it is crucial to establish

whether the Variscan orogen still had excessive crustal

and lithospheric thicknesses at the beginning of the

Stephanian, which would have driven orogenic col-

lapse. Unfortunately, no direct evidence is available,

neither on the palaeotopography of the Variscan oro-

gen nor on crustal thicknesses. Combining several

lines of evidence, a maximum crustal thickness of about

50 km at the onset of the Permo-Carboniferous evolu-

tion seems likely. Estimates for the total lithospheric

thickness can be constrained by the widespread Visean

(330–340 Ma)high-temperature/low-pressuremeta-

morphism and granite magmatism that are so charac-

teristic for the Variscan orogen. The magnitude of this

thermal event, which reached lower crustal tempera-

tures in excess of 900

C, indicates the absence of thick

mantle lithosphere beneath the internal zone of the

Variscan orogen at this time. Thus, if delamination or

convective erosion of the mantle lithosphere occurred

during the Variscan Orogeny, it must have oc-

curred prior to 330 Ma. Consequently, none of these

processes can be invoked to generate surplus potential

energy and gravitational collapse for the Stephanian

to Early Permian evolution.

Quantitative analysis using thermomechanical

finite element models suggests that the gravitational

instability of the Variscan orogen was insufficient to

explain the observed amount and timing of crustal

extension. In order to overcome the finite strength of

the crust and restore a uniform crustal thickness in

the area of the former orogen and its northern fore-

land, tensile plate boundary stresses are required

to have operated until about 285 Ma. The cause of

the far-field stresses can be attributed to the dextral

translation of Laurussia relative to Gondwana during

the Stephanian and Early Permian. Contemporaneous

crustal shortening of 300–400 km in the linked Appa-

lachian–Mauretanide orogen also provides an esti-

mate for the total amount of regional extension that

affected western and central Europe during this stage.

Local extension estimates from, for instance, subsid-

ence analysis and section balancing are available

for only a few basins in the Variscan domain (see

100 EUROPE/Permian Basins

Figure 2). They indicate crustal stretching by a factor

of at least 1.35. However, intrabasin highs, such as

basement ridges and areas with postrift sedimentation

only, do not necessarily represent unextended areas.

This is because diffuse extension and ductile flow of

lower crust towards the zones of maximum upper

crustal extension may have contributed towards

regional crustal thinning.

The decay of the thermal anomaly induced by

Stephanian to Early Permian geodynamic processes,

i.e., thermal contraction of the lithosphere and its re-

equilibration with the asthenosphere, caused long-

lasting subsidence and controlled the formation of

Late Permian and Mesozoic thermal sag basins that

were superimposed on the Permo-Carboniferous

troughs.

See Also

Europe: Permian to Recent Evolution; Variscan Orogeny.

Lava. Palaeozoic: Carboniferous; Permian. Pyroclas-

tics. Sedimentary Environments: Alluvial Fans, Alluvial

Sediments and Settings; Deserts; Lake Processes and

Deposits. Tectonics: Rift Valleys.

Further Reading

Arthaud F and Matte P (1977) Late Paleozoic strike–slip

faulting in southern Europe and northern Africa: results

of a right lateral shear zone between the Appalachians

and the Urals. Geological Society of America, Bulletin

88: 1305–1320.

Benek R, Kramer W, McCann T, et al. (1996) Permo-Car-

boniferous magmatism of the Northeast German Basin.

Tectonophysics 266: 379–404.

Burg J-P, van den Driessche J, and Brun J-P (1994) Syn- to

post-thickening extension in the Variscan Belt of Western

Europe: modes and structural consequences. Ge

´

ologie

de la France 3: 33–51.

Cortesogno L, Cassinism G, Dallagiovannam G, Gaggerom

L, Oggiano G, Ronchi A, Seno S, and Vanossi M (1998)

The Variscan post-collisional volcanism in Late Car-

boniferous Permian sequences of Ligurian Alps,

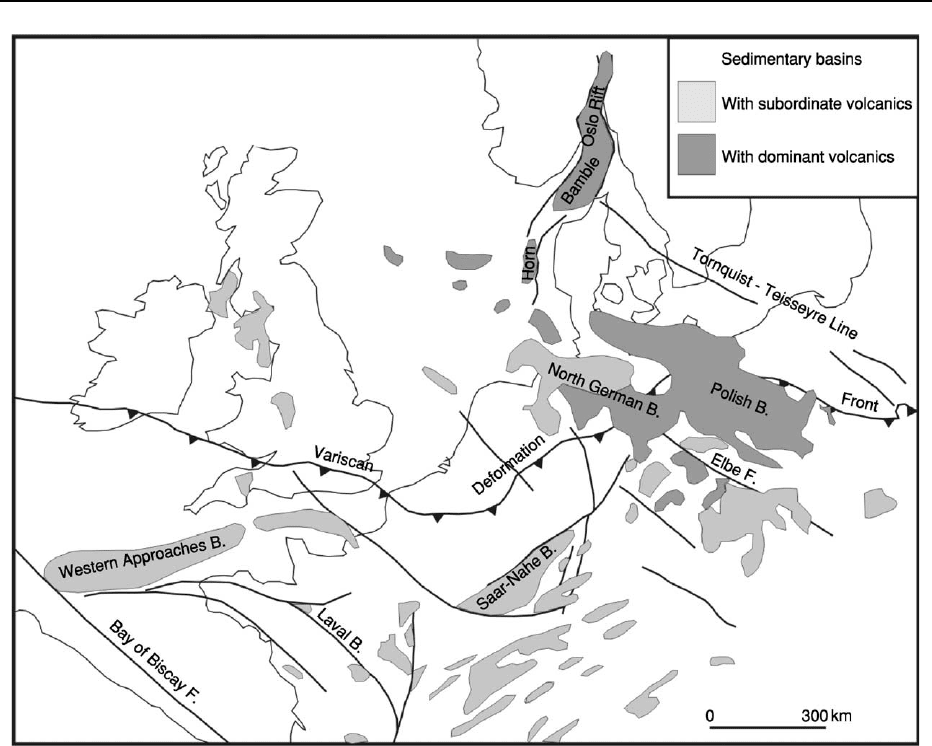

Figure 2 Permo-Carboniferous sedimentary basins and volcanic centres in the Variscan realm. Modified with permission from

Ziegler PA (1990) Geological Atlas of Western and Central Europe. The Hague: Shell Internationale Petroleum Maatschappij.

EUROPE/Permian Basins 101

Southern Alps and Sardinia (Italy): a synthesis. Lithos 45:

305–328.

Finger F, Roberts MP, Haunschmid B, Schermaier A, and

Steyer HP (1997) Variscan granitoids of central Europe:

their typology, potential sources and tectonothermal

relations. Mineralogy and Petrology 61: 67–96.

Floyd PA, Exley CS, and Styles MT (1993) Igneous Rocks

of South-West England. Geological Conservation

Review. vol. 5. London: Chapman & Hall.

Glennie KW (1999) Lower Permian – Rotliegend. In:

Glennie KW (ed.) Petroleum Geology of the North Sea:

Basic Concepts and Recent Advances, pp. 137–173.

Oxford: Blackwell Science.

Henk A (1999) Did the Variscides collapse or were they torn

apart?: a quantitative evaluation of the driving forces for

postconvergent extension in central Europe. Tectonics

18: 774–792.

Plein E (1995) Norddeutsches Rotliegend–Becken. Rotlie-

gend monographie, teil II. Courier Forschungsinstitut

Senckenberg 183: 1–193.

Schaltegger U (1997) Magma pulses in the Central Variscan

Belt: episodic melt generation and emplacement during

lithospheric thinning. Terra Nova 9: 242–245.

Sundvoll B, Neumann E-R, Larsen BT, and Tuen E (1990)

Age relations among Oslo Rift magmatic rocks: implica-

tions for tectonic and magmatic modelling. Tectonophy-

sics 178: 67–87.

Ziegler PA (1990) Geological Atlas of Western and Central

Europe. The Hague: Shell Internationale Petroleum

Maatschappij.

Permian to Recent Evolution

P A Ziegler, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland

ß 2005, Elsevier Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Introduction

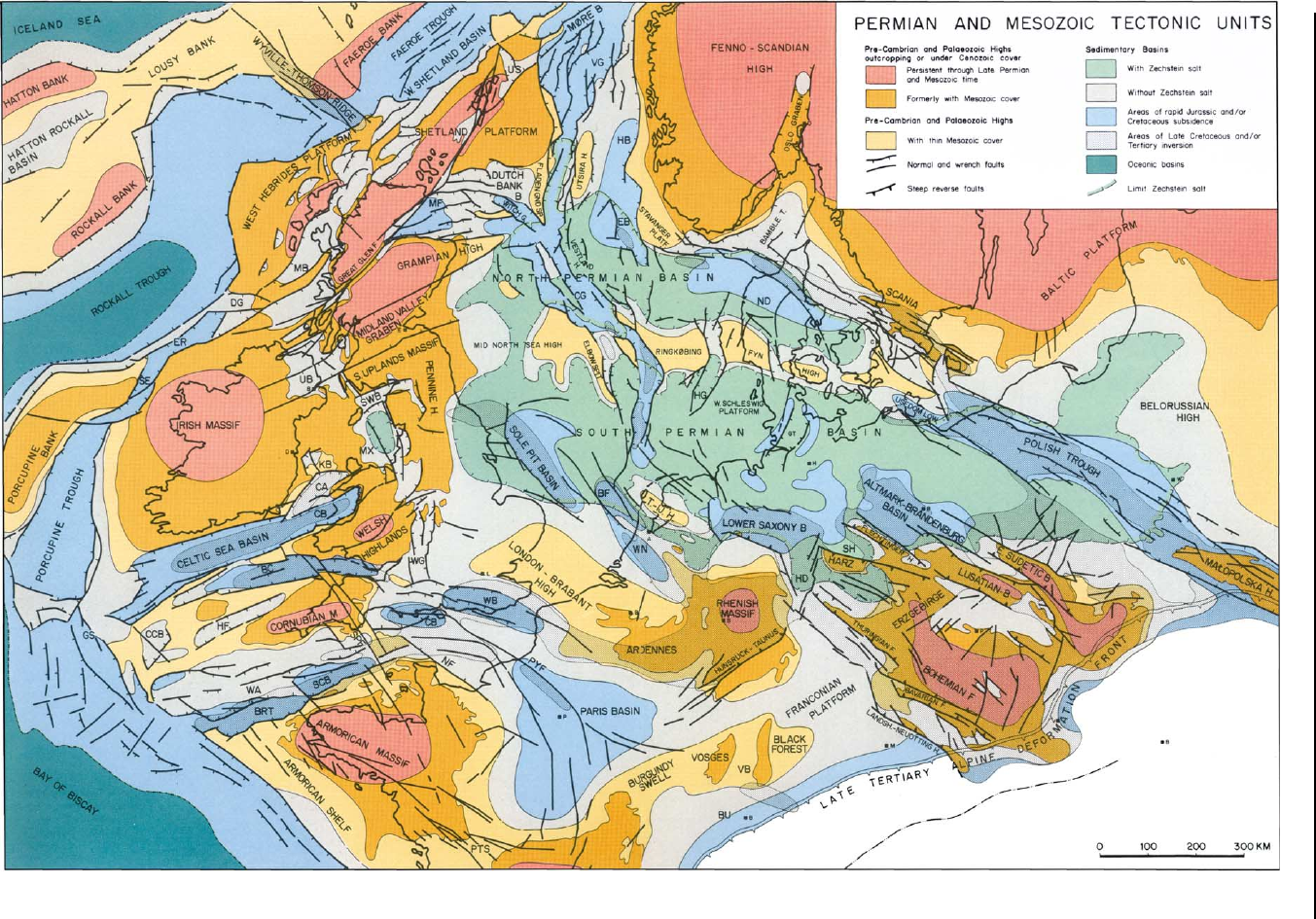

Large parts of Western and Central Europe (WCE)

are occupied by sedimentary basins that contain up

to 8 km thick Permian to Cenozoic series (Figure 1).

These basins are variably underlain by the Pre-

cambrian crust of the East-European-Fennoscandian

Craton (see Europe: East European Craton) and its

Late Precambrian to Early Palaeozoic sedimentary

cover, by the Precambrian Hebridean Craton, by the

Caledonian crust of the British Isles (see Europe:

Caledonides of Britain and Ireland), the North Sea,

Northern Germany and Poland and its Devonian and

Carboniferous sedimentary cover, and by the Varis-

can fold belt in which orogenic activity had ceased at

the end of the Westphalian. The present crustal con-

figuration of WCE bears little relationship to the

Caledonian and Variscan orogenic belts, but is closely

related to the geometry of the Late Permian, Meso-

zoic and Cenozoic sedimentary basins and the Alpine

orogen (Figure 2). This reflects that dynamic pro-

cesses, which governed the evolution of the Late

Permian and younger sedimentary basins, had a

strong impact on the crustal configuration of WCE,

and that the crustal roots of the Caledonian and

Variscan orogens had been destroyed shortly after

their consolidation.

During Permian to recent times, the megatectonic

setting of WCE underwent repeated changes. Corres-

pondingly, dynamic processes controlling the evolu-

tion and partial destruction of sedimentary basins

also changed through time. Therefore, in some

areas, basins of differing tectonic origin are stacked

on top of one other.

The following main stage are recognized in the Late

Permian to recent evolution of WCE, namely: (i) Late

Permian–Early Cretaceous rifting during Pangaea

breakup; (ii) Late Cretaceous–Paleocene rifting and

early Alpine intraplate compression; and (iii) Eocene-

recent opening of the Arctic–North Atlantic and

collisional interaction of the Alpine Orogen with its

foreland.

Background: Late Hercynian Wrench

Tectonics and Magmatism

Following its Late Westphalian consolidation, the

Variscan Orogen (see Europe: Variscan Orogeny)

and its northern foreland were overprinted during

the Stephanian to Early Permian by a system of con-

tinent-scale dextral shears, such as the Tornquist-

Teisseyre, Bay of Biscay, Gibraltar-Minas and Agadir

fracture zones which were linked by secondary sinis-

tral and dextral shear systems. This deformation

reflects a change in the Gondwana-Laurussia conver-

gence from oblique collision to a dextral translation

that was kinematically linked to continued crustal

shortening in the Appalachian (Alleghanian Orogeny)

and the Scythian orogens. Significantly, wrench tec-

tonics and associated magmatic activity abated in the

Variscan domain and its foreland at the transition to

the Late Permian in tandem with the consolidation of

the Appalachian Orogen.

Stephanian to Early Permian wrench-induced dis-

ruption of the Variscan Orogen and its foreland was

accompanied by regional uplift, wide-spread extru-

sive and intrusive mantle-derived magmatic activity

102 EUROPE/Permian to Recent Evolution

Figure 1 Total isopach of Late Permian to Cenozoic sediments.

EUROPE/Permian to Recent Evolution 103

that peaked during the Early Permian, and the subsid-

ence of a multi-directional array of transtensional and

pull-apart basins in which continental clastics accu-

mulated. Basins that developed during this time span

show a complex, polyphase structural evolution, in-

cluding a late phase of transpressional deformation

controlling their partial inversion. Although Stepha-

nian to Early Permian wrench deformation locally

gave rise to the uplift of extensional core complexes,

crustal stretching factors were on a regional scale

relatively low. Nevertheless, the model of the Ceno-

zoic Basin-and-Range Province has been repeatedly

invoked for the Stephanian-Early Permian collapse of

the Variscan Orogen. Yet, kinematics controlling the

development of these two provinces differed: whereas

the collapse of the Variscides was wrench-dominated,

extension dominated the collapse of the Cordillera.

The Stephanian to Early Permian magmatic activity

can be related to wrench-induced reactivation of

Variscan sutures which caused the detachment of

subducted lithospheric slabs, upwelling of the as-

thenosphere, partial delamination and thermal thin-

ning of the mantle-lithosphere, magmatic inflation

of the remnant lithosphere and interaction of

mantle-derived partial melts with the lower crust. In

conjunction with slab detachment and a general re-

organization of the asthenospheric flow patterns, a

system of not very active mantle plumes apparently

welled up to the base of the lithosphere in the area of

the future Southern and Northern Permian basins, the

British Isles and the Oslo Graben, causing thermal

attenuation of the lithosphere and magmatic desta-

bilisation of the crust-mantle boundary. In the domain

of the Variscan Orogen, this accounted for the

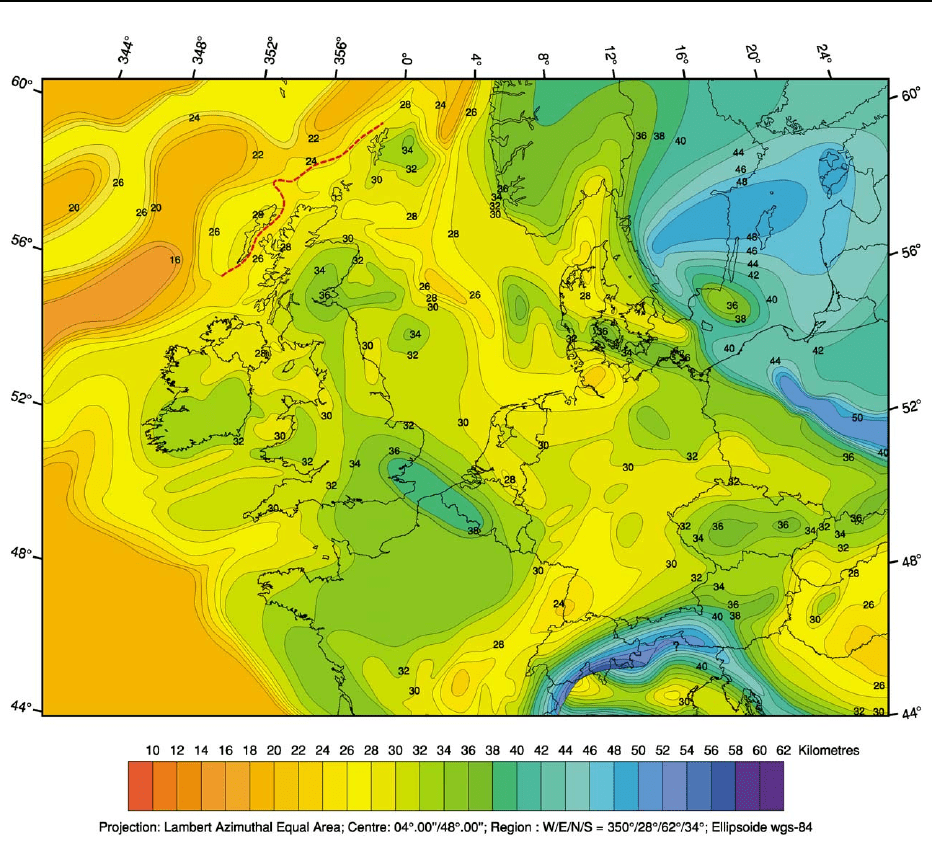

Figure 2 Moho Depth map of Western and Central Europe, contour interval 2 km (after De

`

zes & Ziegler, 2004) (available in digital

format).

104 EUROPE/Permian to Recent Evolution

destruction of its orogenic roots and regional uplift.

By the end of the Early Permian, its crust was thinned

down on a regional scale to 30–35 km, mainly by

magmatic processes and erosional unroofing and

only locally by its mechanical stretching. Moreover,

the thickness of the mantle-lithosphere was reduced to

as little as 50 to 10 km in areas which evolved during

the Late Permian and Mesozoic into intracratonic

thermal sag basins, such as the Southern Permian

and the Paris basins.

Late Permian–Early Cretaceous

Rifting During Pangaea Breakup

Following the Stephanian–Early Permian tectono-

magmatic cycle, the potential temperature of the as-

thenosphere returned quickly to ambient levels

(1300

C). This is indicated by the late Early Permian

extinction of magmatic activity and the onset of re-

gional thermal subsidence of the lithosphere, reflect-

ing the decay of thermal anomalies that had been

introduced during the Permo-Carboniferous. In com-

bination with erosional degradation of the remnant

topography of the Variscan Orogen and cyclically

rising sea-levels, progressively larger areas subsided

below the erosional base level and were incorporated

into a new system of intracratonic basins, comprising

the Northern and Southern Permian basins, the Hes-

sian Depression, the Paris Basin, and the Franconian

Platform (Figure 3). However, in large parts of the

WCE, thermal subsidence of the lithosphere was over-

printed and partly interrupted by the Late Permian–

Early Triassic onset of a rifting cycle which preceded

and accompanied the step-wise break-up of Pangaea.

Major elements of this breakup system were the

southward propagating Arctic-North Atlantic and the

westward propagating Neotethys rift systems. Evolu-

tion of these mega-rift systems was paralleled by the

development of multi-directional grabens in the WCE,

major constituents of which are the North Sea rift,

the North Danish-Polish Trough, the graben systems

of the Atlantic shelves and the Bay of Biscay rift

(Figure 3). Development of these grabens partly in-

volved tensional reactivation of Permo-Carboniferous

fracture systems.

Late Permian

Thermal subsidence of the Northern and Southern

Permian Basin commenced during the late Early

Permian and persisted into Early Jurassic times, as

evidenced by quantitative subsidence analyses, facies

patterns and isopach maps. In these basins sedimen-

tation commenced during the late Early Permian with

the accumulation of the continental Rotliegend red-

bed series which attain a thickness of up to 2300 m in

the axial parts of the-well defined Southern Permian

Basin and of 600 m in the less well-defined Northern

Permian Basin that was severely overprinted by the

Mesozoic North Sea rift.

During the Late Permian, the Norwegian–

Greenland Sea rift, which had come into evidence

during the Late Carboniferous, propagated south-

ward into the North-western Shelf of the British

Isles, opening a seaway through which the Arctic

seas transgressed via the Irish Sea and possibly the

northernmost North Sea into the Northern and

Southern Permian basins which, by this time, had

subsided below the global sea-level (see Europe: Per-

mian Basins). In these basins, the cyclical Zechstein

carbonate, evaporite, and halite series were deposited

under a tectonically quiescent regime. Following the

initial transgression, the axial parts of the Northern

and Southern Permian basins were characterized by

deeper water conditions whereas along their margins

basin-ward prograding carbonate and evaporitic

shelves developed. Facies and thickness changes on

these shelf series provide evidence for minor exten-

sional faulting along the southern margin of the

Southern Permian Basin. Oscillating sea-levels ac-

counted for cyclical restriction of the Northern and

Southern Permian basins in which up to 2000 m of

halites, partly containing polyhalites, were deposited.

During the end-Permian, global low-stand in sea-

level, the Arctic seas withdrew from the WCE into

the area between Norway and Greenland.

Triassic

During the Triassic, the Norwegian–Greenland Sea

rift propagated southwards into the North and

Central Atlantic domain, whilst the Neotethys rift

systems propagated westwards through the Bay of

Biscay and North-west Africa and linked up with

the Atlantic rift system.

During the Early Triassic, the North Sea rift, consist-

ing of the Horda half graben, and the Viking, Murray

Firth, Central, and Horn grabens, was activated and

transected the western parts of the Northern and

Southern Permian basins, whereas their eastern parts

were transected by the North Danish–Polish Trough

(Figure 4). Simultaneously the rift systems of the Alpine

domain, the Bay of Biscay, and the Western Shelves

were activated. The latter included the Porcupine,

Celtic Sea, and Western Approaches troughs. Crustal

extension in the Celtic Sea and Western Approaches

troughs involved at their eastern termination the re-

activation of Permo-Carboniferous shear systems

controlling the subsidence of the Channel Basin and

intermittent destabilization of the Paris thermal sag

basin. Significantly, Triassic–Early Jurassic rifting was

EUROPE/Permian to Recent Evolution 105

Figure 3 PermianandMesozoicTectonicunits.Forlegendsee Figure 16.DetailsofEnclosurefrom Geological Atlas of Western and Central Europe 2ndEdition,PeterA.Zeigler,1990,

published by Shell International Petroleum Mij. B.V., distributed by Geological Society Publishing House, Bath.

106 EUROPE/Permian to Recent Evolution

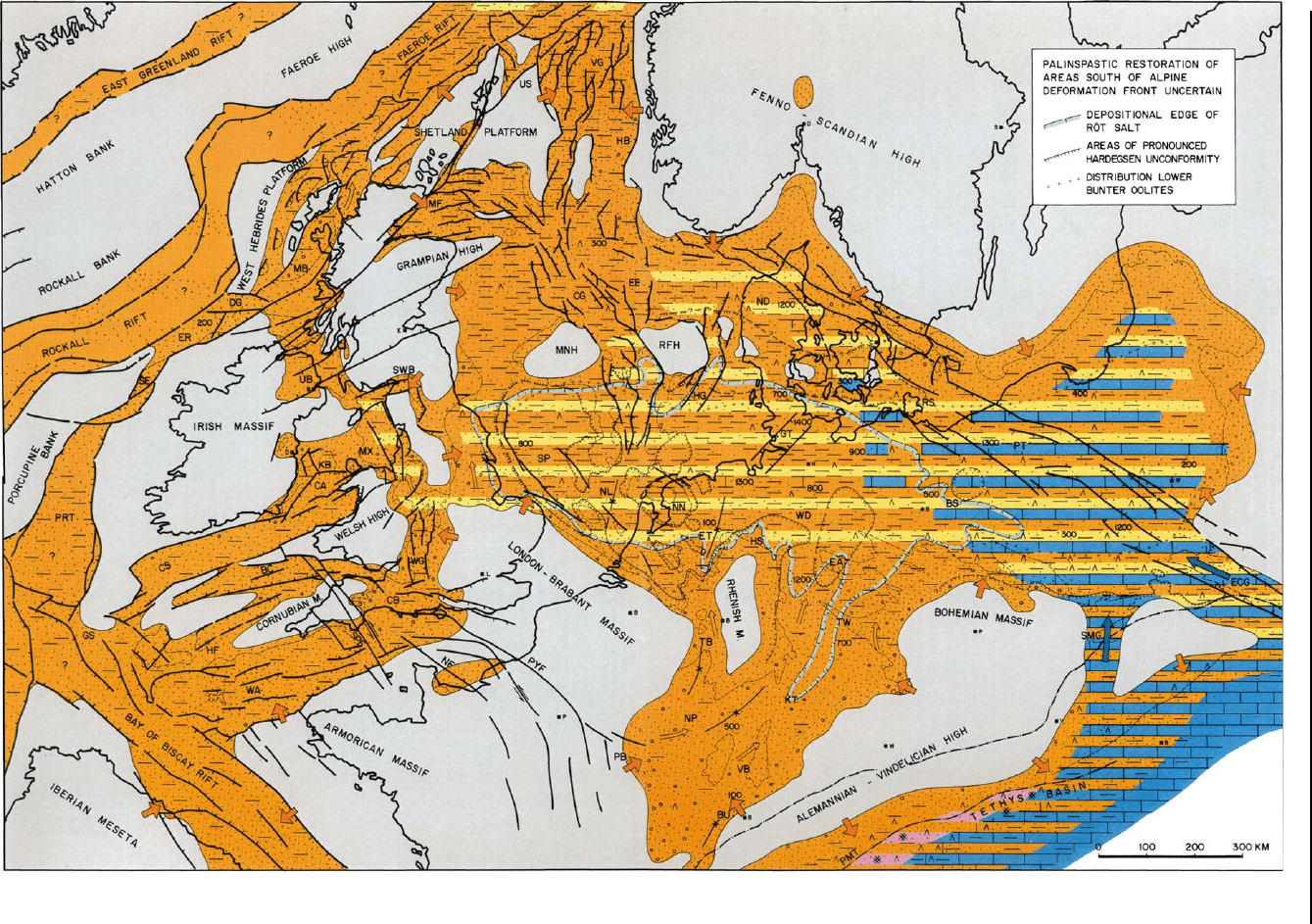

Figure 4 LatePermian,Zechsteinpalaeogeography.Forlegendsee Figure 16.DetailsofEnclosurefrom Geological Atlas of Western and Central Europe2ndEdition,PeterA.Zeigler,1990,

published by Shell International Petroleum Mij. B.V., distributed by Geological Society Publishing House, Bath.

EUROPE/Permian to Recent Evolution 107

accompanied by a low level of volcanic activity with

the exception of the Bay of Biscay, in the evolution of

which wrench faulting compensating for crustal exten-

sion in the Atlantic domain played an important role.

Areas not affected by rifting continued to subside

during the Triassic and Early Jurassic in response to

thermal relaxation of the lithosphere, accounting in

conjunction with eustatically rising sea-levels for a

progressive overstepping of basin margins.

During the Early Triassic, continental to lacustrine

conditions prevailed in the evolving grabens and ther-

mal sag basins of WCE, in which the ‘Bunter’ red-

beds were deposited. Clastics were shed into these

basins from adjacent Variscan and Caledonian

highs, as well as from Fennoscandia. During the late

Early Triassic, the Tethys Seas ingressed the continu-

ously subsiding Southern Permian Basin via the Polish

Trough, giving rise to the deposition of carbonates in

Poland and distal halites in northern Germany and

the Southern North Sea (Figure 5).

As during the Middle Triassic, the trend of highs

that had separated the Northern and Southern Per-

mian basins became gradually overstepped and with

this these basins coalesced, thus forming the compos-

ite North-west European Basin. The Tethys Seas ad-

vanced further into this continuously subsiding basin

complex via the Polish Trough as well as via the Bur-

gundy Trough and the Trier and Hessian depressions,

establishing a broad neritic basin in which the

‘Muschelkalk’ carbonates, evaporites, and halites

were deposited (Figure 6). Furthermore, intermittent

marine transgressions advanced from the Tethyan

shelves via the Bay of Biscay rift into the grabens of

the Western Shelves. By contrast, continental condi-

tions continued to prevail in the grabens of the Central

and Northern North Sea and the North-western Shelf.

With the beginning of the Late Triassic (see Meso-

zoic: Triassic), clastic influx from Fennoscandia and

eastern sources increased, causing the replacement of

the carbonate-dominated Muschelkalk depositional

regime by the evaporitic ‘Keuper’ red-beds containing

halites. Whilst the Polish seaway, which had linked

the Tethys and the North-west European Basin, was

closed, intermittent marine transgressions advanced

through the Burgundy Trough into the evolving Paris

Basin and the continuously subsiding North-west

European Basin, as well as through the Bay of Biscay

rift into the grabens of the Western Shelves. However,

continental conditions persisted in the grabens of the

Central and Northern North Sea and the North-west-

ern Shelf. Only during the Rhaetian did the Arctic

Seas start to advance southwards into the rifted

basins of the North-western Shelf, whilst neritic con-

ditions were established in the broad North-west

European Basin (Figure 7).

The Triassic series attains thicknesses of up to 3 km

in the grabens of the Western Shelves, the North Sea,

and in the Polish Trough, and up to 6 km in the

grabens of the North-western Shelf. In the Northern

and Southern Permian Basins, the diapirism of

Permian salts commenced during the Triassic, and

accounted for local subsidence anomalies.

Jurassic

In conjunction with continued rifting activity and

cyclically rising sea-levels, the Arctic and Tethys

Seas linked up during the Rhaetian–Hettangian, via

the rift systems of the North-western and Western

shelves and the continuously subsiding North-west

European Basin (see Mesozoic: Jurassic). In the open

marine, shale-dominated North-west European

Basin, which occupied much of the Southern

and Central North Sea, Denmark and Germany

(Figure 7), the Belemnitidae (see Fossil Invertebrates:

Cephalopods (Other Than Ammonites)) developed

during the Hettangian and Sinemurian. Persisting

clastic influx from the East-European Platform

allowed only for temporary marine incursions via

the Polish Trough. Similarly, fluvio-deltaic conditions

prevailed in the grabens of the Northern North Sea

until the end-Hettangian to Early Sinemurian when

neritic conditions were also established in these

basins. By Late Simemurian times, this facilitated a

broad faunal exchange between the Boreal and

Tethyan realms and the dispersal of the Belemnitidae.

In response to rising sea-levels and continued

crustal extension, open marine conditions were estab-

lished in the Central Atlantic during the Simemurian,

permitting Tethyan faunas to reach the Pacific by

Pliensbachian times. In basins which were dominated

by the warmer Atlantic and Tethyan waters, carbon-

ates and shales were deposited, whilst shales prevailed

in the North-west European Basin, which was domin-

ated by the cooler Arctic waters. During the Early

Jurassic, repeated stagnant water stratification gave

rise to the deposition of organic-rich shales, forming

important oil source-rocks, for example, in the Paris

Basin and the southern parts of the North-west

European Basin.

During the Late Aalenian–Early Bajocian, the

Arctic seas became separated from the Tethys and

the Central Atlantic in conjunction with the uplift

of a large arch in the Central North Sea from which

clastics were shed into the adjacent continuously

subsiding basins (Figure 8). Uplift of this arch

was associated with major volcanism that may be

related to the impingement of a short-lived mantle

plume. Open marine communications between the

Arctic and the Tethys–Atlantic seas were re-opened

108 EUROPE/Permian to Recent Evolution

Figure 5 Scythian,Buntsandsteinpalaeogeography.Forlegendsee Figure 16.DetailsofEnclosurefrom Geological Atlas of Western and Central Europe2ndEdition,PeterA.Zeigler,1990,

published by Shell International Petroleum Mij. B.V., distributed by Geological Society Publishing House, Bath.

EUROPE/Permian to Recent Evolution 109