Duiker William J., Spielvogel Jackson J. The Essential World History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

The new government faced a sev er e challenge, not only

from the economic crisis but also fr om dissident elements

seeking autonomy or even separation from the republic.

U nder pressur e from the international community, Indone-

sia agreed to grant independence to the onetime P ortuguese

colon y of East Timor, where the majority of the people ar e

Roman Catholics. But violence provok ed by pro-Indonesian

militia units forc ed many refugees to flee the new country .

R eligious tensions ha ve also erupted between M uslims and

Christians elsewhere in the archipelago , and M uslim rebels in

western Sumatra continue to agitate for a political system

based on strict adherence to fundamentalist Islam.

In direct elections held in 2004, General Susilo

Yudhoyono defeated Megawati Sukarnoputri and ascended

to the presidency. The new chief executive promised a

new era of political stability, honest government, and

economic reform but faces a number of severe challenges.

Concerned about high wages and the risk of terrorism, a

number of foreign firms have relocated their factories

elsewhere in Asia, forcing thousands of workers to return

to the countryside. Pressure from traditional Muslims to

abandon the nation’s secular tradition and move toward

the creation of an Islamic state continues to grow. That

the country was able to hold democratic elections in the

midst of such tensions holds some promise for the future.

Vietnam and Burma Elsewhere in

the region, progress toward democ-

racy has been mixed. In Vietnam, the

trend has been toward a greater pop-

ular role in the governing process.

Elections for the unicameral parlia-

ment are more open than in the past.

The government remains suspicious

of Western-style democracy, however,

and represses any opposition to the

Communist Party’s guiding role over

the state.

Only in Burma (now renamed

Myanmar), where the military has

been in complete control since the

early 1960s, have the forces of

greater popular par ticipation been

v irtually silenced. Even there, how-

ever, t he power of the ruling regime

of General Ne Win (1911--2002)

and his successors, known as

SLORC, has been vocally challenged

by Aung San Suu Ky i (b. 1945),

the admired daughter of one of

theheroesofthecountry’sstruggle

for national liberation after World

War II. Massive flooding after a

powerful ty phoon in 2008 laid bare

the regime’s incompetence in dealing with a humani-

tarian crisis.

Crisis and Recovery The trend toward more repre-

sentative systems of government has been due in part to

increasing prosperity and the growth of an affluent and

educated middle class. Although Indonesia, Burma, and

the three Indochinese states are still overwhelmingly

agrarian, Malaysia and Thailand have been undergoing

relatively rapid economic development.

In the late summer o f 1997, ho wever, these economic

gains were threatened and popular faith in the ultimate

benefits of globalization was shaken as a financial crisis swept

through the r egion. The crisis was triggered by a number of

problems, including growing budget deficits caused by ex-

cessive gov ernment expenditures on ambitious development

projects, irr esponsible lending and in vestment practic es by

financial institutions, and an ov ervaluation of local curren-

cies relative to the U.S. dollar. An underlying cause of these

problems was the prevalenc e of backr oom deals between

politicians and business leaders that temporarily enriched

both groups at the cost of eventual ec onomic dislocation.

As local currencies plummeted in value, the Interna-

tional Monetary Fund agreed to provide assistance, but

only on the condition that the governments concerned

Soccer, a Global Obsession. Professional soccer has become the most popular sport in the

world. It offers a diversion from daily drudgery and promotes intense patriotism as each nation

supports its team. Moreover, children the world over enjoy playing soccer, even when there are no

playing fields in the vicinity. Shown here is an informal match held in an ancestral Chinese temple in

Hoi An, a town in central Vietnam that once served as a major entry point for European, Chinese, and

Japanese merchants who took part in the regional trade network. Today, Vietnam is once again

opening its doors to the outside world.

c

William J. Duiker

764 CHAPTER 30 TOWARD THE PACIFIC CENTURY?

permit greater transparency in their economic systems and

allow market forces to operate more freely, even at the

price of bankruptcies and the loss of jobs. By the early

2000s, ther e were signs that the economies in the region

had weathered the crisis and were beginning to recover.

But the massive tsunami that struck in December 2004 was

another setback to economic growth, as well as a human

tragedy of enormous proportions.

Regional Conflict and Cooperation:

The Rise of ASEAN

In addition to their continuing internal challenges, South-

east Asian states have been hampered by serious tensions

among themselves. Some of these tensions were a conse-

quence of historical rivalries and territorial disputes that had

been submerged during the long era of colonial rule.

Cambodia, for example, has bickered with both of its

neighbors, Thailand and Vietnam, over mutual frontiers

dra wn up originally by the French for their own conv enience.

After the fall of Saigon and the reunification of Viet-

nam under Communist rule in 1975, the lingering bor der

dispute between Cambodia and Vietnam erupted again. In

April 1975, a brutal rev olutionary regime under the lead-

ership of the Khmer Rouge dictator P ol Pot (c. 1928--1998)

came to power in Cambodia and proceeded to carry out

the massacre of more than one million Cambodians. Then,

claiming that vast territories in the Mekong delta had been

seized from Cambodia by the V ietnamese in previous

centuries, the Khmer Rouge regime launched attacks across

the c ommon border . In response, Vietnamese forc es in-

vaded Cambodia in December 1978 and installed a pro-

Hanoi regime in Phnom Penh. Fearful of Vietnam ’s

increasing power in the region, China launched a brief

attack on Vietnam to demonstrate its displeasure.

The outbreak of war among the erstwhile Communist

allies aroused the concern of other countries in the

neighborhood. In 1967, several non-Communist countries

had established the Association of Southeast Asian Nations

(ASEAN). Composed of Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand,

Singapore, and the Philippines, ASEAN at first concen-

trated on cooperative social and economic endeavors, but

after the end of the Vietnam War , it cooperated with other

states in an effort to force the Vietnamese to withdra w

from Cambodia. In 1991, the V ietnamese finally withdrew,

and a new government was formed in Phnom Penh.

The growth of ASEAN from a weak collection of

diverse states into a stronger organization whose members

cooperate militarily and politically has helped provide the

nations of Southeast Asia with a more cohesive voice to

represent their interests on the world stage. That Vietnam

was admitted into ASEAN in 1996 should provide both

Hanoi and its neighbors with greater leverage in dealing

with China---their powerful neighbor to the north.

Daily Life: Town and Country

in Contemporary Southeast Asia

The urban-rural dichotomy observed in India also is found

in Southeast Asia, where the cities resemble those in the West

while the countryside often appears little changed from

precolonial days. In cities such as Bangkok, Manila, and

Jakarta, br oad boulevards lined with skyscrapers alternate

with muddy lanes passing through neighborhoods packed

with wooden shacks topped b y thatch or rusty tin roofs.

Nev ertheless, in recent decades, millions of Southeast Asians

have fled to these urban slums. Although most available jobs

are menial, the pay is better than in the villages.

Traditional Customs, Modern Values The urban mi-

grants change not only their physical surroundings but their

attitudes and values as well. Sometimes the mov e leads to a

decline in traditional beliefs. Nev ertheless, Buddhist,

M uslim, and Confucian beliefs remain strong, even in cos-

mopolitan cities such as Bangkok, Jakarta, and Singapore.

This preference for the traditional also shows up in lifestyle.

N ative dr ess---or an eclectic blend of Asian and Western

dress---is still common. Traditional music, art, theater, and

dance remain popular, although Western rock music has

CHRONOLOGY

Southeast Asia Since 1945

Philippines becomes independent 1946

Beginning of Franco-Vietminh War 1946

Burma becomes independent 1948

Republic of Indonesia becomes independent 1950

Malaya becomes independent 1957

Beginning of Sukarno’s ‘‘guided democracy’’

in Indonesia

1959

Militar y seizes power in Indonesia 1965

Founding of ASEAN 1967

Fall of Saigon to North Vietnamese forces 1975

Vietnamese invade Cambodia 1978

Corazon Aquino elected president

in the Philippines

1986

Vietnamese withdraw from Cambodia 1991

Vietnam becomes a member of ASEAN 1996

Islamic and student protests in Indonesia 1996--1997

Suharto steps down as president of Indonesia 1998

Tsunami causes widespread death and

destruction throughout the region

2004

Antigovernment protests erupt in Thailand 2008

S

OUTHEAST ASIA 765

become fashionable among the

young, and Indonesian filmmakers

complain that Western films are be-

ginning to dominate the market.

Changing Roles for Women One

of the most significant changes that

has taken place in Southeast Asia in

recent decades is in the role of

women in society. In general,

women in the region have histori-

cally faced fewer restrictions on their

activities and enjoyed a higher status

than women elsewhere in Asia.

Nevertheless,theywerenottheequal

of men in every respect. With inde-

pendence, Southeast Asian women

gained new rights. Virtually all of the

constitutions adopted by the newly

independent states granted women

full legal and political rights, in-

cluding the right to work. Today,

women have increased opportunities

for education and have entered ca-

reers previously reserved for men.

Women have become more active in

politics, and as we have seen, some

have served as heads of state.

Yet women are not truly equal to

men in any country in Southeast Asia.

In Vietnam, women are legally equal

to men, yet until recently no women had served in the

Communist P arty’ s ruling politburo. In Thailand, M alaysia,

and Indonesia, women rarely hold senior positions in go v-

ernment service or in the boardr ooms of major corporations.

A Region in Flux

Today, the Western image of a Southeast Asia mir ed in the

Vietnam conflict and the tensions of the Cold War has be-

come a memory. In ASEAN, the states in the region have

created the framework for a regional organization that can

serve their common political, ec onomic, technological, and

security interests. A few members of ASEAN are already on

theroadtoadvanceddevelopment.

To be sure, there are continuing signs of trouble. The

financial crisis of the late 1990s aroused serious political

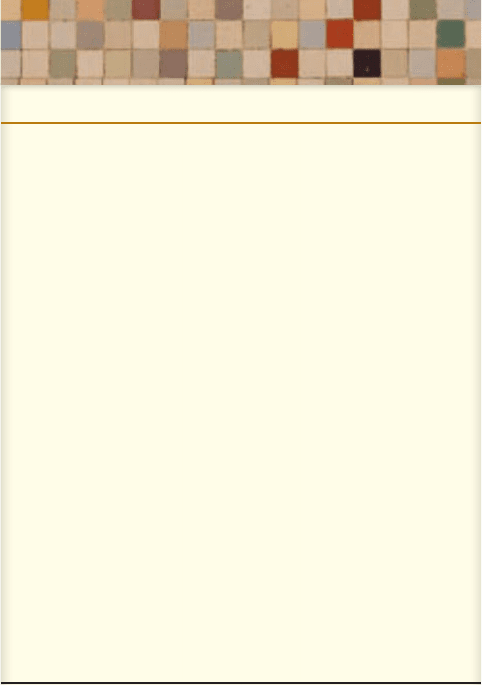

Holocaust in Cambod ia. When the Khmer Rouge seized power in Cambodia in April 1975, they

immediately emptied the capital of Phnom Penh and systematically began to eliminate opposition

elements throughout the country. Thousands were tortured in the infamous Tuol Sleng prison and then

marched out to the countryside, where they were massacred. Their bodies were thrown into massive

pits. The succeeding government disinterred the remains, which are now displayed at an outdoor

museum on the site. Today, a measure of political and economic stability has begun to return to the

country. The commandant of the prison, Comrade Deuch, is currently on trial in Phnom Penh.

c

William J. Duiker

c

William J. Duiker

One World, One Fashion . One of the negative aspects of tourism is

the eroding of distinctive ethnic cultures, even in previously less traveled

areas. Nevertheless, fashions from other lands often seem exotic and enticing.

This village chief from Flores, a remote island in the Indonesian archipelago,

seems very proud of his designer sunglasses.

766 CHAPTER 30 TOWARD THE PACIFIC CENTURY?

unrest in Indonesia, and the region’s economies, though

recovering, still bear the scars of the crisis. There are

disquieting signs that al-Qaeda has established a presence

in the region. Myanmar remains isolated and appears

mired in a state of chronic underdevelopment and brutal

military rule. The three states of Indochina remain po-

tentially unstable and have not yet been fully integrated

into the region as a whole. All things considered, however,

the situation is more promising today than would have

seemed possible a generation ago. Unlike the case in

Africa and the Middle East, the nations of Southeast Asia

have put aside the bitter legacy of the colonial era to

embrace the wave of globalization that has been sweeping

the world in the post--World War II era.

Japan: Asian Giant

Q

Focus Question: How did the Allied occupation after

World War II change Japan’s political and economic

institutions, and what remained unchange d?

In August 1945, Japan was in ruins, its cities destroyed, its

vast Asian empire in ashes, its land occupied by a foreign

army. Half a century later, Japan had emerged as the

second-greatest industrial power in the world, democratic

in form and content and a source of stability throughout

the region. Japan’s achievement spawned a number of

Asian imitators.

The Transformation of Modern Japan

For five years after the end of the war in the Pacific, Japan

was governed by an Allied administration under the

command of U.S. general Douglas MacArthur. As com-

mander of the occupation administration, MacArthur

was responsible for demilitarizing Japanese society, de-

stroying the Japanese war machine, trying Japanese

civilian and military officials charged with war crimes,

and laying the foundations of postwar Japanese society.

One of the sturdy pillars of Japanese militarism had

been the giant business cartels, known as zaibatsu. Allied

policy was designed to break up the zaibatsu into smaller

units in the belief that corporate concentration not only

hindered competition but was inherently undemocratic

and conducive to political authoritarianism. Occupation

planners also intended to promote the formation of in-

dependent labor unions in order to lessen the power of

the state over the economy and provide a mouthpiece for

downtrodden Japanese workers. Economic inequality in

rural areas was to be reduced by a comprehensive land

reform program that would turn the land over to those

who farmed it. Finally, the educational system was to be

remodeled along American lines so that it would turn out

independent individuals rather than automatons subject

to manipulation by the state.

The Allied program was an ambitious and even au-

dacious plan to remake Japanese society and has been

justly praised for its clear-sighted vision and altruistic

motives. Parts of the program, such as the constitution,

the land reforms, and the educational system, succeeded

brilliantly. But as other concerns began to intervene,

changes or compromises were made that were not always

successful. In particular, with the rise of Cold War sen-

timent in the United States in the late 1940s, the goal of

decentralizing the Japanese economy gave way to the

desire to make Japan a key partner in the effort to defend

East Asia against international communism. Convinced

of the need to promote economic recovery in Japan, U.S.

policy makers began to show more tolerance for the

zaibatsu. Concerned about growing radicalism within the

new labor movement, U.S. occupation authorities placed

less emphasis on the independence of the labor unions.

The Cold War also affected U.S. foreign relations with

Japan. On September 8, 1951, the United States and other

former belligerent nations signed a peace treaty restoring

Japanese independence. In turn, Japan renounced any

claim to such former colonies or territories as Taiwan,

Korea, and southern Sakhalin and the Kurile Islands (see

Map 30.3). On the same day, Japan and the United States

signed a defensive alliance and agreed that the latter could

maintain military bases on the Japanese islands. Japan was

now formally independent but in a new dependency re-

lationship with the United States. A provision in the new

constitution renounced war as an instrument of national

policy and prohibited the raising of an army.

Politics and Government The Allied occupation ad-

ministrators started with the conviction that Japanese ex-

pansionism was directly linked to the institutional and

ideological foundations of the M eiji Constitution. Acc ord-

ingly , they set out to change Japanese politics into some-

thing closer to the pluralistic model used in most Western

nations. Yet a number of characteristics of the postwar

Japanese political system reflected the tenacity of the tra-

ditional political culture. Although Japan had a multiparty

system with two major parties, the Liberal Democrats and

the Socialists, in practice there was a ‘‘go vernment party’’

and a permanent opposition---the Liberal Democrats were

not v oted out of office for thirty years.

That tradition changed suddenly in 1993, when

the ruling Liberal Democrats, shaken by persistent reports

of corruption and cronyism between politicians and

business interests, failed to win a majority of seats

in parliamentary elections. The new coalition govern-

ment, however, quickly split into feuding factions, and

in 1995, the Liberal Democrats returned to power.

JAPAN:ASIAN GIANT 767

Successive prime ministers proved

unable to carry out promised re-

forms, and in 2001, Junichiro

Koizumi (b. 1942), a former min-

ister of health and welfare, was

elected prime minister. His per-

sonal charisma raised expectations

that he might be able to bring

about significant changes, but bu-

reaucratic resistance to reform and

chronic factionalism within the

Liberal Democratic Party thwarted

his efforts, and since he left office

in 2006, the desire for change has

remained largely unrealized.

Japan, Inc. The challenges for

future Japanese leaders include

not only curbing persistent polit-

ical corruption but also reducing

the government’s involvement in

the economy. Since the Meiji pe-

riod, the government has played

an active role in mediating man-

agement-labor disputes, establish-

ing price and wage policies, and

subsidizing vital industries and

enterprises producing goods for

export. This government inter-

vention in the economy was once

cited as a key reason for the effi-

ciency of Japanese industry and

the emergence of the country as

an industrial giant. In rec ent years,

however, as the economy remained

mired in rec ession, the govern-

ment’s actions have increasingly

come under fire. Japanese firms now argue that deregula-

tion is needed to enable them to innovate to keep up with

the competition. Such reforms, however, have been resisted

by powerful government ministries.

Atoning for the Past Lingering social problems also

need to be addressed. Minorities such as the eta (now

known as the Burakumin) and Korean residents in Japan

continue to be subjected to legal and social discrimina-

tion. For years, official sources were reluctant to divulge

growing evidence that thousands of Korean women were

conscripted to serve as prostitutes (euphemistically called

‘‘comfort women’’) for Japanese soldiers during the war,

and many Koreans living in Japan contend that such

prejudicial attitudes continue to exist. Representatives of

the ‘‘comfort women’’ have demanded both financial

compensation and a formal letter

of apology from the Japanese

government for the treatment

they received during the Pacific

War. Negotiations over the issue

have been under way for several

years.

Japan’s behavior during

World War II has been an espe-

cially sensitive issue. During the

early 1990s, critics at home and

abroad charged that textbooks

printed under the guidance

of the Ministry of Education

did not adequately discuss the

atrocities committed by the

Japanese government and armed

forces during World War II.

Other Asian governments were

particularly incensed at Tokyo’s

failure to accept responsibility for

such behavior and demanded a

formal apology. The government

expressed remorse, but only in

the context of the aggressive ac-

tions of all colonial powers dur-

ing the imperialist era.

The Economy Nowhere are the

changes in postwar Japan so vis-

ible as in the economic sector,

where Japan developed into a

major industrial and technologi-

cal power in the space of a cen-

tury, surpassing such advanced

Western societies as Germany,

France, and Great Britain.

Although this ‘‘Japanese miracle’’ has often been

described as beginning after the war as a result of the

Allied reforms, Japanese economic growth in fact began

much earlier, with the Meiji reforms, which helped

transform Japan from an autocratic society based on

semifeudal institutions into an advanced capitalist

democracy.

As noted, the officials of the Allied occupation

identified the Meiji economic system with centralized

power and the rise of Japanese militarism. But with the

rise of Cold War tensions, the policy of breaking up the

zaibatsu was scaled back. Looser ties between companies

were still allowed, and a new type of informal relation-

ship, sometimes called the keiretsu, or ‘‘interlocking ar-

rangement,’’ began to take shape. Through such

arrangements among suppliers, wholesalers, retailers, and

CHINA RUSSIA

NORTH

KOREA

SOUTH

KOREA

Nagasaki

Hiroshima

Osaka

Nagoya

Yokohama

Tokyo

Kobe

Kyoto

HOKKAIDO

SAKHALIN

Kurile Islands

HONSHU

SHIKOKU

KYUSHU

S

e

a

o

f

J

a

p

a

n

(

E

a

s

t

S

e

a

)

P

a

c

i

f

i

c

O

c

e

a

n

R

y

u

k

y

u

I

s

l

a

n

d

s

300 Miles

400 Kilometers0

0

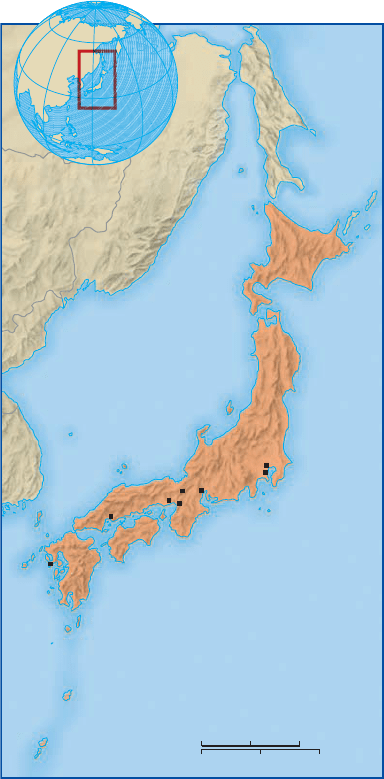

MAP 30.3 M odern Japan. Shown here are the

four main islands that comprise the contemporary

state of Japan.

Q

Which is the largest?

768 CHAPTER 30 TOWARD THE PACIFIC CENTURY?

financial institutions, the zaibatsu system was recon-

stituted under a new name.

The occupation administration had more success

with its program to reform the agricultural system. Half

of the population still lived on farms, and half of all

farmers were still tenants. Under the land reform pro-

gram, all lands owned by absentee landlords and all

cultivated landholdings over an established maximum

were sold on easy credit terms to the tenants. The

program created a strong class of yeoman farmers, and

tenants declined to about 10 percent of the rural

population.

During the next fifty years, Japan re-created the

stunning results of the Meiji era. In 1950, the Japanese

gross domestic product was about one-third that of Great

Britain or France. Today, it is larger than both put to-

gether and well over half that of the United States. Japan

is one of the greatest exporting nations in the world, and

its per capita income equals or surpasses that of most

advanced Western states.

In the last decades, however, the Japanese economy

has run into serious difficulties, raising the question of

whether the Japanese model is as appealing as many

observers earlier declared. A rise in the value of the yen

hurt exports and burst the bubble of investment by

Japanese banks that had taken place under the umbrella

of government protection. Lacking a domestic market

equivalent in size to the United States, in the 1990s the

Japanese economy slipped into a recession that has not

yet abated. Economic conditions worsened in 2008 and

2009 as Japanese exports declined significantly as a con-

sequence of the global economic downturn.

These economic difficulties have placed heavy pres-

sure on some of the vaunted features of the Japanese

economy. The tradition of lifetime employment created a

bloated white-collar workforce and has made downsizing

difficult. Today, job security is on the decline as increasing

numbers of workers are being laid off. A disproportionate

burden has fallen on women, who lack seniority and

continue to suffer from various forms of discrimination

in the workplace.

A final change is that s lowly but inexorabl y, the

Japanese market is beginnin g to open up t o interna-

tional competition. Greater exposure to foreign com-

petition may improve the performance of Japanese

manufacturers. In recen t years, Japanese consu mers have

become increasingly critical of the quality of some do-

mestic products, provoking one cabinet minister to

complain about ‘‘sloppiness and complacency’’ among

Japanese firms. One apparent reason for the country’s

recent quality problems is the cost-cutting measures

adopted by Japanese companies to meet the challenges

from abroad.

A Society in Transition

During the occupation, Allied planners set out to change

social characteristics that they believed had contributed to

Japanese aggressiveness before and during World War II.

The new educational system removed all references to

filial piety, patriotism, and loyalty to the emperor while

emphasizing the individualistic values of Western civili-

zation. The new constitution and a revised civil code

eliminated remaining legal restrictions on women’s rights

to obtain a divorce, hold a job, or change their domicile.

Women were guaranteed the right to vote and were en-

couraged to enter politics.

Such efforts to remake Japanese behavior through

legislation were only partially successful. During the past

sixty years, Japan has unquestionably become a more

individualistic and egalitarian society. At the same time,

many of the distinctive characteristics of traditional

Japanese society have persisted to the present day, al-

though in somewhat altered form. The emphasis on

loyalty to the group and community relationships, for

example, is reflected in the strength of corporate loyalties

in contemporary Japan.

Emphasis on the work ethic also remains strong. The

tradition of hard work is taught at a young age. The

Japanese school year runs for 240 days a year, compared

with 180 days in the United States, and work assignments

outside class tend to be more extensive. The results are

impressive: Japanese schoolchildren consistently earn

higher scores on achievement tests than children in other

advanced countries. At the same time, this devotion to

success has often been accompanied by bullying by

teachers and what Americans might consider an oppres-

sive sense of conformity (see the box on p. 771).

By all accounts, independent thinking is on the in-

crease in Japan. In some cases, it leads to antisocial be-

havior, such as crime or membership in a teenage gang.

Usually, it is expressed in more indirect ways, such as the

recent fashion among young people of dyeing their hair

brown (known in Japanese as ‘‘tea hair’’). Because the

practice is banned in many schools and generally frowned

on by the older generation (one police chief dumped a

pitcher of beer on a student with brown hair whom he

noticed in a bar), many young Japanese dye their hair as a

gesture of independence. When seeking employment or

getting married, however, they often return their hair to

its natural color.

One of the more tenacious legacies of the past in

Japanese society is sexual inequality. Although women are

now legally protected against discrimination in employ-

ment, very few have reached senior levels in business,

education, or politics. Women now constitute nearly

50 percent of the workforce; but most are in retail or

JAPAN:ASIAN GIANT 769

service occupations, and their average salary is only about

half that of men. There is a feminist movement in Japan,

but it has none of the vigor and mass support of its

counterpart in the United States.

Religion and Culture When Japan was opened to the

West in the nineteenth century, many Japanese became

convinced of the superiority of foreign ideas and in-

stitutions and were especially interested in Western reli-

gion and culture. Although Christian converts were few,

numbering less than 1 percent of the population, the

influence of Christianity was out of proportion to the size

of the community.

Today, Japan includes almost 1.5 million Christians,

along with 93 million Buddhists. Many J apanese also follow

Shinto , no longer identified with reverence for the emperor

and the state. As in the West, increasing urbanization has

led to a decline in the practice of organized r eligion, al-

though evangelical sects have pr oliferated in recent years.

The largest and best-known sect is Soka Gakkai, a lay

Buddhist organization that has attracted millions of fol-

lowers and formed its own political party, the Komeito. Zen

Buddhism retains its popularity, and some businesspeople

seek to use Zen techniques to learn how to focus on will-

power as a means of outwitting a competitor.

Western literature, art, and music have also had a

major impact on Japanese society. After World War II,

many of the writers who had been active before the war

resurfaced, but now their writing reflected demoralization.

Many were attracted to existentialism, and some turned to

hedonism and nihilism. For these disillusioned authors,

defeat was compounded by fear of the Americanization of

postwar Japan. One of the best examples of this attitude

was the novelist Yukio Mishima (1925--1970), who led a

crusade to stem the tide of what he described as America’s

‘‘universal and uniform ‘Coca-Colonization’’’ of the world

in general and Japan in particular.

3

Mishima’s ritual sui-

cide in 1970 was the subject of widespread speculation and

transformed him into a cult figure.

One of Japan’s most serious-minded contemporary

authors is Kenzaburo Oe (b. 1935). His work, rewarded

with a Nobel Prize for Literature in 1994, focuses on

Japan’s ongoing quest for modern identity and purpose.

His characters reflect the spiritual anguish precipitated by

the collapse of the imperial Japanese tradition and the

subsequent adoption of Western culture---a trend that Oe

contends has culminated in unabashed materialism, cul-

tural decline, and a moral void. Yet unlike Mishima, Oe

does not wish to reinstill the imperial traditions of the

past but rather seeks to regain spiritual meaning by re-

trieving the sense of communality and innocence found

in rural Japan.

Other aspects of Japanese culture have also been

influenced by Western ideas. Western music is very

popular in Japan, and scores of Japanese classical musi-

cians have succeeded in the West. Even rap music has

gained a foothold among Japanese youth, although

without the association with sex, drugs, and violence that

From Conformity to Countercultu re. Traditionally, schoolchildren in Japan

have worn uniforms to promote conformity with the country’s communitarian social

mores. In the left photo, young students dressed in identical uniforms are on a field trip

to Kyoto’s Nijo Castle, built in 1603 by Tokugawa Ieyasu. Recently, however, a youth

counterculture has emerged in Japan. On the right, fashion-conscious teenagers with

‘‘tea hair’’—heirs of Japan’s long era of affluence—revel in their expensive hip-hop

outfits, platform shoes, and layered dresses. Such dress habits symbolize the growing

revolt against conformity in contemporary Japan.

c

William J. Duiker

c

Barry Cronin/Getty Images

770 CHAPTER 30 TOWARD THE PACIFIC CENTURY?

it has in the United States. As one singer remarked,

‘‘We’ve been very fortunate, and we don’t want to bother

our Moms and Dads. So we don’t sing songs that would

disturb parents.’’

4

The Little Tigers

Q

Focus Questions: What factors have contributed to the

economic success achieved by the Little Tigers? To

what degree have they applied the Japanese model in

forging their developmental strategies?

The success of postwar Japan in meeting the challenge

from the capitalist West soon caught the eye of other

Asian nations. By the 1980s, several smaller states in the

region---known collectively as the ‘‘Little Tigers’’---had

successively followed the Japanese example.

South Korea: A Peninsula Divided

In 1953, the Korean peninsula was exhausted from three

years of bitter fraternal war, a conflict that took the lives

of an estimated four million Koreans on both sides of the

38th parallel. Although a cease-fire was signed in July

1953, it was a fragile peace that left two heavily armed and

mutually hostile countries facing each other suspiciously.

North of the

truce line was the

People’s Republic

of Korea (PRK), a

police state under

the dictatorial rule

of the Communist

leader Kim Il Sung

(1912--1994). To

the south was the

Republic of K orea,

under the equally

autocratic Presi-

dent Syngman

Rhee (1875--1965),

a fierce anti-

Communist who

had led the resis-

tance to the north-

ern invasion. After

GROWING UPINJAPAN

Japanese schoolchildren grow up in a much more

regimented environment than U.S. children experi-

ence. Most Japanese schoolchildren, for example,

wear black-and-white uniforms to school. These

regulations are examples of rules adopted by middle school

systems in various parts of Japan. The Ministry of Education in

Tokyo concluded that these regulations were excessive, but

they are probably typical.

School Regulations, Japanese Style

1. Boys’ hair should not touch the eyebrows, the ears, or the top

of the collar.

2. No one should have a permanent wave, or dye his or her hair.

Girls should not wear ribbons or accessories in their hair. Hair

dryers should not be used.

3. School uniform skirts should be ___ centimeters above the

ground, no more and no less (differs by school and region).

4. Keep your uniform clean and pressed at all times. Girls’ middy

blouses should have two buttons on the back collar. Boys’ pant

cuffs should be of the prescribed width. No more than 12 eye-

lets should be on shoes. The number of buttons on a shirt and

tucks in a shirt are also prescribed.

5. Wear your school badge at all times. It should be positioned

exactly.

6. Going to school in the morning, wear your book bag strap on

the right shoulder; in the afternoon on the way home, wear it

on the left shoulder. Your book case thickness, filled and un-

filled, is also prescribed.

7. Girls should wear only regulation white underpants of 100%

cotton.

8. When you raise your hand to be called on, your arm should ex-

tend forward and up at the angle prescribed in your handbook.

9. Your own route to and from school is marked in your student

rule handbook; carefully observe which side of each street you

are to use on the way to and from school.

10. After school you are to go directly home, unless your parent

has written a note permitting you to go to another location.

Permission will not be granted by the school unless this other

location is a suitable one. You must not go to coffee shops.

You must be home by ___ o’clock.

11. It is not permitted to drive or ride a motorcycle, or to have a

license to drive one.

12. Before and after school, no matter where you are, you repre-

sent our school, so you should behave in ways we can all be

proud of.

Q

What is the apparent purpose of these regulations? Why

does Japan appear to place more restrictions on students’

behavior than most Western countries do?

Korea

Bay

Sea of

Japan

(East Sea)

CHINA

NORTH

KOREA

Y

a

l

u

R

.

T

u

m

e

n

R

.

Kwangju

Inchon

Seoul

Pusan

Panmunjom

Pyongyang

Yellow

Sea

JAPAN

SOUTH

KOREA

K

o

r

e

a

S

t

r

a

i

t

38th Parallel

0 100 200 Miles

0 150 300 Kilometers

Cease-fire line

The Korea n Penin sula Sinc e 1953

THE LITTLE TIGERS 771

several years of harsh rule in the Republic of Korea, marked

by government corruption, fraudulent elections, and police

brutality, demonstrations broke out in the capital city of

Seoul in the spring of 1960 and forced Rhee into retirement.

In 1961, a coup d’

etat in South Korea placed General

Chung Hee Park (1917--1979) in power. The new regime

promulgated a new constitution, and in 1963, Park was

elected president of a civilian government. He set out to

foster recovery of the economy from decades of foreign

occupation and civil war. Because the private sector had

been relatively weak under Japanese rule, the government

played an active role in the process by instituting a series

of five-year plans that targeted specific industries for

development, promoted exports, and funded infrastruc-

ture development.

The program was a solid success. Benefiting from the

Confucian principles of thrift, respect for education, and

hard work, as well as from Japanese capital and tech-

nology, Korea gradually emerged as a major industrial

power in East Asia. The largest corporations---including

Samsung, Daewoo, and Hyundai---were transformed into

massive conglomerates called chaebol, the Korean

equivalent of the zaibatsu of prewar Japan. Korean busi-

nesses began to compete actively with the Japanese for

export markets in Asia and throughout the world.

But like man y other countries in the region, South

Korea was slow to develop democratic principles. Although

his government functioned with the trappings of democ-

racy, P ark continued to rule by autocratic means and

suppressed all forms of dissidenc e. In 1979, Park was as-

sassinated. But after a brief interregnum of democratic

rule, in 1980 a new military go v ernment under General

Chun Doo Hwan (b. 1931) seized power. The new r egime

was as authoritarian as its predecessors, but after student

riots in 1987, by the end of the decade opposition to au-

tocratic rule had spr ead to much of the urban population.

National elections were finally held in 1989, and

South Korea reverted to civilian rule. Successive presidents

sought to rein in corruption while cracking down on the

chaebols and initiating contacts with the Communist re-

gime in the PRK on possible steps toward eventual re-

unification of the peninsula. After the Asian financial

crisis in 1997, economic conditions temporarily worsened,

but they have since recovered, and the country is in-

creasingly competitive in world markets today. Symbolic

of South Korea’s growing self-confidence is the nation’s

new president, Lee Myung-bak (b. 1941), elected in 2007.

An ex-mayor of Seoul, he is noted for his rigorous efforts

to beautify the city and improve the quality of life of his

compatriots, including the installation of a new five-day

workweek. His most serious challenge, however, is to

protect the national economy, which is heavily dependent

on exports, from the ravages of the recent economic crisis.

In the meantime, relations with North Korea, now

under the dictatorial rule of Kim Il Sung’s son Kim Jong Il

(b. 1941) and on the verge of becoming a nuclear power,

remain tense. Multinational efforts to persuade the re-

gime to suspend its nuclear program continue, although

North Korea claimed to have successfully conducted a

nuclear test in 2009.

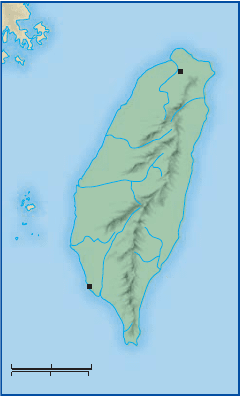

Taiwan: The Other China

After retreating to Taiwan following their defeat by the

Communists, Chiang Kai-shek ’s government, which con-

tinued to refer to itself as

the Republic of China

(ROC), contended that it

remained the legitimate

representativ e of the Chi-

nese people and would

eventually return in tri-

umph to the mainland.

The Nationalists had

much more success on

Taiwan than they had

achieved on the mainland.

In the relatively secure

environment provided by

a security treaty with the

United States, signed

in 1954, the ROC was able

to concentrate on eco-

nomic growth without

worrying about a Com-

munist invasion.

The government moved rapidly to create a solid ag-

ricultural base. A land reform program led to the re-

duction of rents, and landholdings over 3 acres were

purchased by the government and resold to the tenants at

reasonable prices. At the same time, local manufacturing

and commerce were strongly encouraged. By the 1970s,

Taiwan had become one of the most dynamic industrial

economies in East Asia.

In contrast to the Communist regime in the People’s

Republic of China (PRC), the ROC actively maintained

Chinese tradition, promoting respect for Confucius and

the ethical principles of the past, such as hard work,

frugality, and filial piety. Although there was some cor-

ruption in both the government and the private sector,

income differentials between the wealthy and the poor

were generally less than elsewhere in the region, and the

overall standard of living increased substantially. Health

and sanitation improved, literacy rates were quite high,

and an active family planning program reduced the rate

of population growth.

CHINA

Taipei

Kaohsiung

Pacific

Ocean

Pescadores

Islands

T

a

i

w

a

n

S

t

r

a

i

t

60 Miles

100 Kilometers0

0

Modern Ta iwan

772 CHAPTER 30 TOWARD THE PACIFIC CENTURY?

After the death of Chiang Kai-shek in 1975, t he

ROC slowly began to move toward a more representat ive

form of government, including elections and legal op-

position parti es. A national election in 1992 resulted in a

bare m ajority for the Nationalists over strong opposition

from the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). B ut po-

litical liberalization had it s dangers; some members of

the DPP began to agitate for an i ndependent Republic of

Taiwan, a possibility that aroused concern within the

Nationalist government in Taipei and frenzied hostility

in the PRC. The election of DPP leader Chen Shui-bian

(b. 1950) as ROC president in March 2000 angered

Beijing, which threatened to invade Taiwan should the

island continue to delay unification with th e mainland.

The return to power of the Nationalist Party in 2008 has

at least for the time being eased relations with mainland

China.

The United States continues to provide defensive

military assistance to the Taiwanese armed forces and has

made it clear that it supports self-determination for the

people of Taiwan and that it expects the final resolution

of the Chinese civil war to be by peaceful means. In the

meantime, economic and cultural contacts between

Taiwan and the mainland are steadily increasing. Never-

theless, the Taiwanese have shown no inclination to ac-

cept the PRC’s offer of ‘‘one country, two systems,’’ under

which the ROC would accept the PRC as the legitimate

government of China in return for autonomous control

over the affairs of Taiwan.

Singapore and Hong

Kong: The Littlest Tigers

The smallest but by no means

the least successful of the Little

Tigers are Singapore and Hong

Kong. Both contain large

populations densely packed

into small territories. Singa-

pore, once a British colon y and

briefly a part of the state of

Malaysia, is now an indepen-

dent nation. Hong Kong was a

British colony until it was re-

turned to PRC control in 1997.

In recent years, both have

emerged as industrial power -

houses, with standards of liv-

ing well above those of their

neighbors.

The success of Singapore

must be ascribed in good

measure to the will and en-

ergy of its political leaders.

When it became independent in August 1965, Singapore’s

longtime position as an entrepo

ˆ

t for trade between the

Indian Ocean and the South China Sea was on the wane.

Within a decade, Singapore’s role and reputation had

dramatically changed. Under the leadership of Prime

Minister Lee Kuan-yew (b. 1923), the government culti-

vated an attractive business climate while engaging in

public works projects to feed, house, and educate its two

million citizens. The major components of success have

been shipbuilding, oil refineries, tourism, electronics, and

finance---the city-state has become the banking hub of the

entire region.

As in the other Little T igers, an authoritarian political

system has guaranteed a stable environment for economic

growth. Until his retir ement in 1990, Lee Kuan-yew and his

P eople ’s Action Party dominated Singapore politics, and

opposition elements wer e intimidated into silence or ar -

rested. The prime minister openly declar ed that the Western

model of pluralist

democracy was

not appropriate for

Singapore. Confu-

cian values of thrift,

hard work, and obe-

dience to authority

were promoted as

the ideology of the

state (see the box on

p . 774).

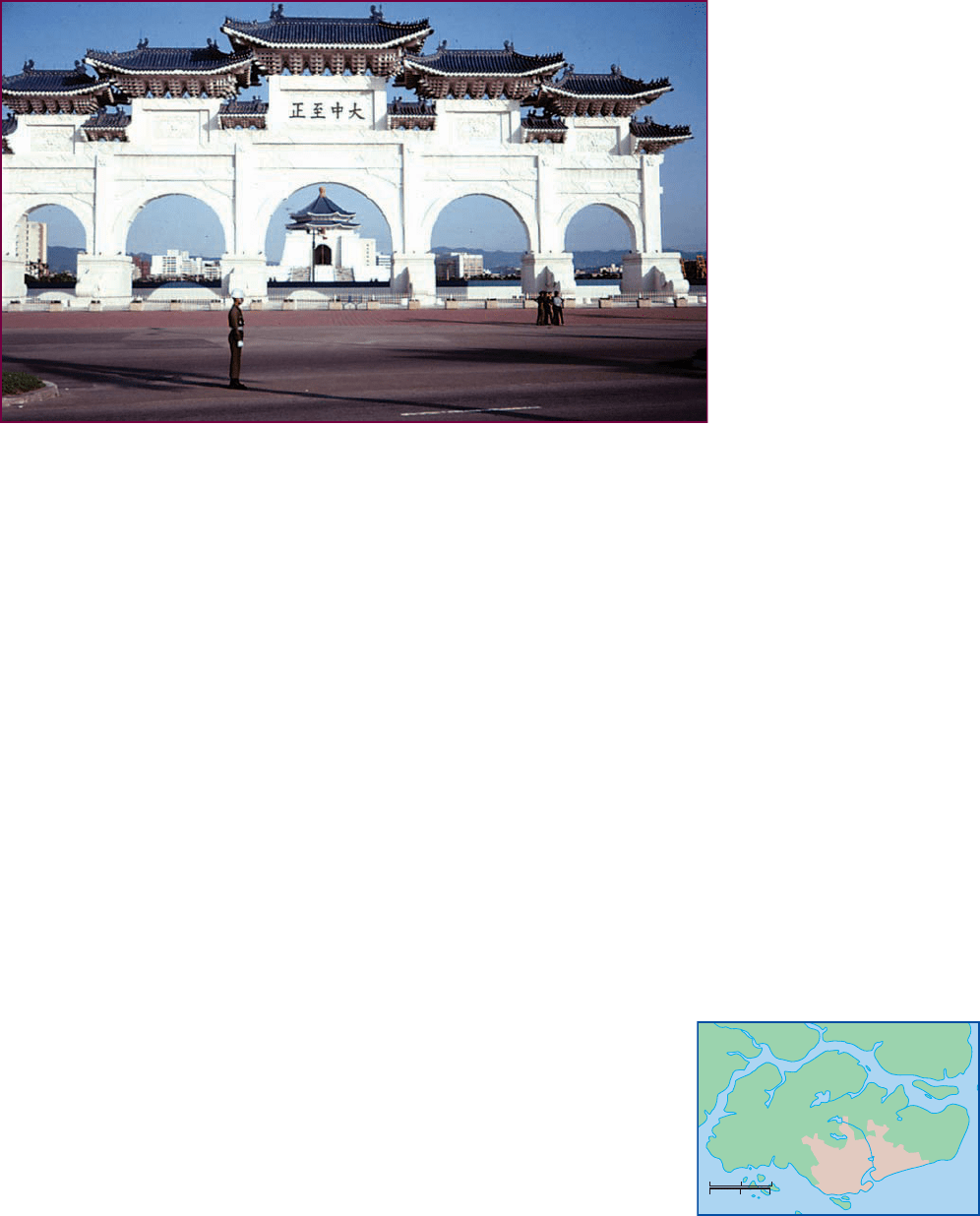

The Chi ang Ka i-shek Mem orial in Taipei. While the Chinese government on the mainland attempted

to destroy all vestiges of traditional culture, the Republic of China on Taiwan sought to preserve the cultural

heritage as a link between past and present. This policy is graphically displayed in the mausoleum for Chiang

Kai-shek in downtown Taipei, shown in this photograph. The mausoleum, with its massive entrance gate, not

only glorifies the nations’s leader but recalls the grandeur of old China.

c

William J. Duiker

Singapore

SINGAPORE

MALAYSIA

Singapore

Strait

S

i

n

g

a

p

o

r

e

R

.

6 Miles

10 Kilometers0

0

The Republic of Singapore

THE LITTLE TIGERS 773