Duffy Christopher. Red Storm On The Reich (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

bridgehead, where two all-arms armies and the Fourth Tank

Army were reinforced by Rybalko's much-travelled Third

Guards Tank Army, which was retrieved from Upper Silesia.

This 'Lower Silesian Operation' was due to begin on 8 Feb-

ruary. Meanwhile the Russians reshuffled their forces, en-

larged their bridgeheads and made an isolated push by way

of Grottkau deeper into Silesia.

The German Forces on the Eve

of the Lower Silesian Operation

Since 20 January German Army Group A (soon to be re-

designated Army Group Centre) had been in the keeping of

Colonel-General Ferdinand Schörner, who was renowned as

probably the leading exponent of the National Socialist style of

leadership in the Wehrmacht. Hitler had boundless trust in

him, and Goebbels testified that Schörner was

no chairborne or map general; most of the day he spends

with the fighting troops, with whom he is on terms of con-

fidence, though he is very strict. In particular he has taken

a grip on the so-called 'professional stragglers,' by which he

means men who continually manage to absent themselves in

critical situations and vanish to the rear on some pretext or

other. His procedure with such types is fairly brutal; he hangs

them on the nearest tree with a placard announcing: 'I am a

deserter and have declined to defend German women and

children.' (Goebbels, 1977, 80)

While a stability of sorts was achieved on Army Group A's

sector which faced Zhukov, the state of affairs further south in

Lower Silesia was dangerously fluid. Here the Germans (Gen-

eral Fritz Gräser's Fourth Panzer Army) had a scratch garrison

and two infantry divisions in or near Breslau, but otherwise

only about as many field divisions as Konev had full armies.

CHRISTOPHER DUFFY

128

The units which had been cut off beyond the Oder were lost

beyond recall, and the German High Command feared that the

Soviets might seize a further prize—the containers of liquid

poison gas that were held near the village of Dyhernfurth, on

the enemy bank of the Oder below Breslau.

It was one of the oddities of the Second World War that none

of the belligerents went so far as to employ poison gas in war-

fare. However, they continued the necessary research and de-

velopment, and at Dyhernfurth the Germans had large stocks

of some of their latest and deadliest toxins. The Fourth Panzer

Army was told that it was not enough to raid the factory and

blow up the tanks, for sufficient residue would be left to be

analysed by the Russians. The Germans must therefore seize

the factory and hold it long enough to permit the liquid to be

pumped into the Oder. Gräser entrusted this delicate operation

to Major-General Max Sachsenheimer.

At first Fourth Panzer Army envisaged a conventional attack,

complete with an artillery bombardment, and a set-piece assault

delivered by two companies of 'dismounted' parachutists who

were summoned from neighbouring army groups. Sachsen-

heimer analysed his task more closely and grasped that the

essence must be to secure enough time to enable the pumping-

out to go ahead undisturbed. This could best be achieved by a

swift and silent strike with the forces immediately at hand,

formed into a little battle group of several hundred infantry,

two batteries of dual-purpose 88-mm guns, and a light pioneer

assault boat company with eighty-one craft. Two scientists and

eighty technicians provided the expert help.

On a personal reconnaissance Sachsenheimer saw that the

railway bridge to Dyhernfurth was intact, apart from the two

spans nearest the 'German' bank, and that it was guarded only

by two machine-guns, one on each side of the railway em-

bankment on the far bank. Beyond the Oder the railway curved

left past Dyhernfurth, and a spur line led directly into the

wooded compound of the chemical factory, which meant that

the Germans could not go far astray if they simply followed

RED STORM ON THE REICH

129

the line of the tracks. Russian soldiers could be heard singing

in Dyhernfurth Castle: 'But perhaps "singing" was not the right

word for the noises which were carried to our ears. It was a

bawling which grew in volume, and from which we concluded

that the Russians were in a state of increasing drunkenness'

(Ahlfen, 1977, 129). Sachsenheimer gained Gräser's approval

for the plan, and the motley force approached the river on the

morning of 5 February.

The main body made directly for the bridge along the axis

of the railway, Major Josse and a small team disposed of the

Russian machine-gunners with hardly a sound, while 88-mm

guns were deployed behind the river embankment on the near

side, and twenty-six assault boats were assigned to transport

a diversionary crossing which began two-and-a-half kilometres

downstream half an hour later.

On the far side of the Oder the technicians and their escort

penetrated the deserted compound of the factory, while the

rest of the main force of infantry threw out a screen of Pan-

zerfaust detachments on all the approaches to the plant. The

pumps were found to be in full working order, and the engines

were started only sixty-five minutes after the operation had

begun.

The Soviets reacted only after 1300. They made their first

attack with a force of eighteen tanks from the direction of Sei-

fersdorf to the north, but the thrust was checked by the screen

of Panzerfausts. Just before nightfall a much more dangerous

push developed from Kranz, a short distance to the east, when

a body of eight tanks moved towards the railway by the bridge,

threatening to cut off all the Germans who were on the right

bank of the river. Now the 88-mm guns came into their own:

The barrels were cranked up until they projected just above

the top of the Oder dyke, they were laid rapidly on their

targets, and they spouted their familiar long tongues of red-

dish-yellow fire with a sharp crack. The range was just 750

CHRISTOPHER DUFFY

130

6. The Dyhernfurth raid, 5 February 1945

metres, and the sounds of the impacts followed the dis-

charges with scarcely an interval. (Ahlfen, 1977, 132)

Six of the Russian tanks were hit, and most of them burst

instantly into flames. The Germans had won a few more hours

of darkness to complete their work in the compound. When

the containers had finally been drained, the scientists delivered

a written attestation to Sachsenheimer, who in turn radioed

army headquarters with the news that his mission had been

accomplished. In the course of the night the raiding force with-

drew to the left bank of the Oder without any further incident.

Almost certainly the Russians never noticed the significance of

what had taken place under their noses.

The operation at Dyhernfurth on 5 February does not figure

largely in the annals of war, but it was a classic of its kind,

notable for the accurate selection of the aim, simplicity of con-

RED STORM ON THE REICH

131

ception, and speed and economy in the execution. The two

companies of parachutists, by the way, never made an ap-

pearance.

Cheering news also came from beyond Gräser's right flank,

where the Seventeenth Army sent in a two-divisional counter-

attack which pushed back the Russian force that had penetrated

through Grottkau. On 7 February the populations of Ottmachau

and Neisse were delighted to see German tanks rolling east-

wards once more: 'The sun has come out again. So the German

Wehrmacht really does exist! The whole population, both na-

tives and refugees, has turned out on the streets to cheer the

troops' (Ahlfen, 1977, 121).

The Lower Silesian Operation,

8-24 February 1945

The little triumphs at Dyhernfurth and Grottkau were entirely

eclipsed by the Soviet offensive which burst from the Oder

bridgeheads on 8 February. The Lower Silesian Operation was

opened by a single fifty-minute bombardment, and at 0600 the

troops and tanks crossed the start lines. The ground had been

softened by the thaw, and on some sectors the Russians moved

with apparent slowness. Near Herzogswalde on the sector of

the 40th Infantry Division (Fourth Panzer Army) a newly

formed company beat off an initial attack by a battalion and

two tanks. Reserve Captain Heinze writes:

An illuminating round from a Russian artillery piece had

set fire to a haystack next to the cattle shed. We salvaged a

stock of ammunition and drove the animals out. Meanwhile

the two tanks had advanced from Rädlitz to Ischerey—one

of the machines halted next to our farmstead and the other

to the west. I called for a Panzerfaust and wriggled towards

the tank. This Panzerfaust was a new and unfamiliar model,

CHRISTOPHER DUFFY

132

and I had to experiment before I could release the safety

device. There was a crack and a shower of sparks. It was a

hit! Three infantrymen who had been riding the tank now

slid off. The tank burnt, and the ammunition blew up. My

comrades fired a Panzerschreck [heavier version of the Pan-

zerfaust] at the other tank, but they missed, and the vehicle

drove into cover behind our barn—which I unfortunately

discovered too late. The back doors were blocked. I hastened

across the burning floor of the stalls so as to take it under

fire from the window, but it had not found the situation to

its liking, and it made back to the wood, from where it rained

shells on us.

Lieutenant Jung, the adjutant, was severely wounded (a

shot through the lung). I received a splinter in my left heel.

A shell blew a cow into bloody tatters. ... I was left alone

shooting from the window in the roof . . . my assault rifle

jammed, and I snatched up an ordinary rifle. Further tanks

were rolling from Rädlitz. It was madness to offer further

resistance in this location. (Ahlfen, 1977, 112-13)

Madness indeed—Schörner had deployed the Fourth Panzer

Army against the Steinau bridgehead, and the Seventeenth

Army against the Ohlau bridgehead, but by the end of the day

the cohesion of the Germans was collapsing and the Russian

armour had penetrated up to sixty kilometres.

The city of Breslau was now almost isolated by the Russian

tide, but it stood like a rock against the centre of Konev's of-

fensive, effectively checking the progress of two of the all-arms

armies. Konev therefore ordered Rybalko's Third Guards Tank

Army to execute a left about-turn and link up behind Breslau

with the forces which were advancing from the Ohlau bridge-

head. It was a reproduction on a smaller scale of the Third

Guard Tank Army's move behind the flank and rear of the

Upper Silesian Industrial Region a couple of weeks earlier.

On 10 and 11 February the main force of the army roared

eastwards along the autobahn between Liegnitz and Breslau,

RED STORM ON THE REICH

133

announcing that the Soviets intended to encircle the Silesian

capital. The Germans extricated what they could of their 269th

Infantry Division through the narrowing gap, but on 15 Feb-

ruary the ring around Breslau was closed when all-arms armies

from the two bridgeheads joined hands just outside the city

and the Third Guards Tank Army positioned itself to the west.

Some 35,000 German regular troops and 80,000 civilians were

cut off:

Meanwhile the whole area inside the encirclement was

seething. The encircled garrison units rushed hither and

thither in search of an exit. Sometimes they fought desper-

ately, but more commonly surrendered. An enormous num-

ber of cars and horse-drawn carriages packed with people

jammed the roads south-west of Breslau; having lost all hope

of finding even the smallest gap, they were now rolling back

to the city. (Konev, 1969, 57)

Now that Breslau had been encircled, the run of uncontrol-

lable German disasters in Silesia came to an end, and by the

middle of February the fighting on this theatre began to stabilise

and cohere in a distinctive way, forming a pattern that endured

for the next two months. In essence, Konev's 1st Ukrainian

Front was now contained inside a right angle of German forces:

• The Fourth Panzer Army which faced east, and tried to hold

the lines of the little rivers which flowed north to the middle

Oder. This deployment barred Konev's further progress

westwards into the German heartland.

• The Seventeenth Army which occupied the axis of the Su-

deten hills and faced north, thereby threatening Konev's very

long left or southern flank. It was a mirror image of the

buildup of German forces in Pomerania which hovered over

Zhukov's right flank.

By diverting Rybalko against Breslau, Konev had weakened

the westward push of his right wing from the old Steinau

CHRISTOPHER DUFFY

134

bridgehead. Lelyushenko's Fourth Tank Army advanced with-

out support, but although it was not counted as one of the more

dashing of the tank forces, it reached the Lausitzer Neisse as

early as 14 February. This unaccustomed daring was punished

when on the same day the Fourth Panzer Army carried out a

pincer movement against the Russian communications imme-

diately to the west of the Bober stream—with the Grossdeutsch-

land Panzer Corps thrusting north, and the XXIV Panzer Corps

pushing south. The two German formations had been through

a great deal together in recent weeks. On this occasion they

were unable to effect a junction, but for a time the Russian army

was cut off and fighting for its life. 'A bitter two-day battle

developed. Everyone was caught up in the combat, from private

soldiers to generals' (Lelyushenko, 1970, 400).

The Germans broke off their attack on 19 February, by which

time Lelyushenko had cleared his communications and the

Third Guards Tank Army and the Fifty-Second Army had come

up to support him respectively to left and right. The Russians

closed up to the Lausitzer Neisse on a frontage of one hundred

kilometres. Here they were checked by six German divisions,

which were fighting very bitterly. German reinforcements were

arriving on this sector, and Konev also had to take stock of the

increasing danger to his left flank and rear, and on 24 February

he declared the Lower Silesian Operation closed. The Soviets

abandoned most of their bridgeheads beyond the Lausitzer

Neisse, retaining only a hotly contested lodgment between

Forst and Guben. Thus the Russians finally lost the impetus of

the attack which had begun on the Vistula on 12 January.

The German Counterattacks from the South—

Lauban 2-5 March, and Striegau 9-14 March 1945

The Central European highland chain, which was here called

the Sudetens, extended along Konev's left flank. Together with

the fringes of the plain at their foot, they were held by the

RED STORM ON THE REICH

135

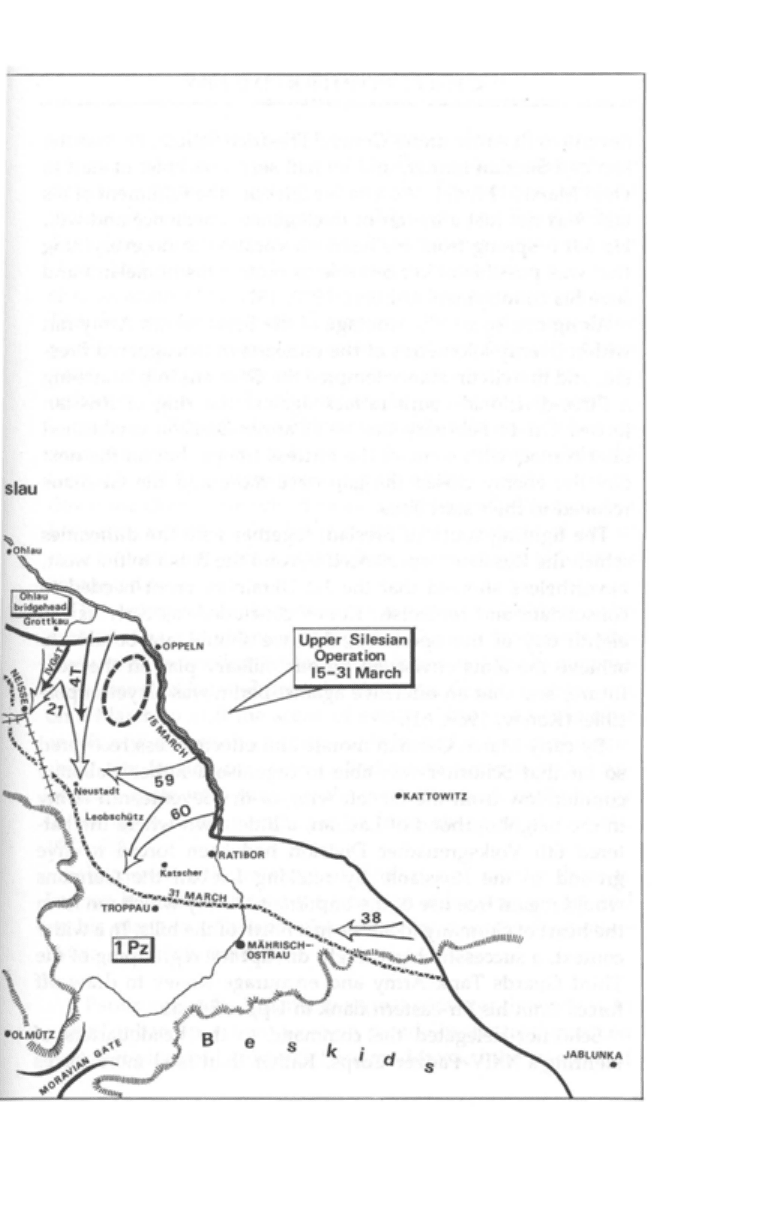

7. Silesia, February-March 1945

slau

B

e

s

Upper

Silesian

Operation

15-31

March

eKATTOWITZ

k

d

s

JABLUNKA

•